Abstract

Research is limited on how nurses in community settings manage ethical conflicts. To address this gap, we conducted a study to uncover the process of behaviors enacted by community nurses when experiencing ethical conflicts. Guided by Glaserian grounded theory, we developed a theoretical model (Moral Compassing) that enables us to explain the process how 24 community nurses managed challenging ethical situations. We discovered that the main concern with which nurses wrestle is moral uncertainty (“Should I be addressing what I think is a moral problem?”). Moral Compassing comprises processes that resolve this main concern by providing community nurses with the means to attain the moral agency necessary to decide to act or to decide not to act. The processes are undergoing a visceral reaction, self-talk, seeking validation, and mobilizing support for action or inaction. We also discovered that community nurses may experience continuing distress that we labeled moral residue.

Keywords: home care, caregivers, community and public health, ethics, moral perspectives, health care, work environment, theory development, nursing

Health care professionals may experience ethical conflict when their moral beliefs and values differ from the values underlying clinical or organizational decisions implemented in their workplace. Decisions may be clinical practice decisions impacting clients and family members or administrative procedural decisions impacting clients, family members, and employees (e.g., budget allocations or organizational policies). Ethical conflict has been the topic of empirical study in recent decades (e.g., Carnevale, 2013; Gaudine et al., 2011b). There has been a resurgence of research interest in acute care issues, such as the ethics of providing or withholding unwarranted advanced treatment given a client’s individual life circumstances. Research on the topic has been conducted in hospital settings, and thus, ethical conflict arising during community-based care has received relatively little attention.

Research examining the ethics of administrative decisions was initiated several decades ago due in large part to escalating health care costs and budget restraints (e.g., Gaudine & Beaton, 2002). Given that more funds are distributed to acute care institutions than to community health centers, the majority of this research was also conducted in hospital settings (e.g., Gaudine et al., 2011a).

Registered nurses in Canada are bound by the Canadian Nurses Association (CNA) Code of Ethics that guides ethical practice behaviors (CNA, 2017a). The Code consists of nursing values and responsibilities that serve to protect the public by ensuring the delivery of safe, competent care. When ethical conflicts are experienced by nurses, there is a risk that quality care delivery is in jeopardy, thus making ethical conflict a significant research topic. The very fact that conflict occurs may serve as an indicator or warning that care or decision-making is suboptimal; although one may argue ethical conflict may also occur when care is optimal and health care providers hold different moral viewpoints. It is also important to identify and understand nurses’ ethical conflicts because unresolved conflict in the workplace has long been associated with lower morale and burnout (Lamb & Storch, 2012; Mack, 2013; Rodney & Starzomski, 1993; Yarling & McElmurry, 1986). In fact, more recently, Canadian researchers, after conducting a longitudinal study of Canadian nurses, reported that ethical conflict in the workplace was associated with increased stress, absenteeism, and turnover intent (Gaudine & Thorne, 2012).

In developed countries, as hospitals opened intensive care units and the complexity of client care escalated, hospital ethics committees came into existence. By the 1970s, many hospitals in Canada and elsewhere had formed ethics committees and, or, hired an ethicist to address ethical conflict associated with liability issues, and gradually, these became the norm for hospitals. A 2008 Canadian survey revealed that 85% of respondents had a committee for advising on ethical situations (Gaudine et al., 2010). In contrast, community-based agencies had not incorporated established ethics committees at the same rate despite the fact that well over a decade ago Canadian researchers discovered that professionals working in community health centers wanted ethics support (Racine & Hayes, 2005). In part because there have been few studies examining ethical conflict arising during community-based care, ethics committees or supports for managing ethical conflict have been slower to develop. In some cases where community services have become part of a larger health care organization that includes hospital(s) settings, the hospital’s ethics committee provides the ethics consultation function; however, the committee may not understand the unique issues associated with home care, for example, Fry-Revere (1992). To address this need, Norway is in the early stages of implementing ethics reflection groups in community health care agencies (Lillemoen & Pedersen, 2015; Magelssen et al., 2016).

With clients being transferred from hospitals earlier, an aging population, and the increasing incidence of chronic disease, it is probable that community-based health care professionals are frequently challenged by ethical situations. Given that community nurses may have little or no access to ethics committees or ethicists due to fact that, generally, most resources are based in hospitals, it is particularly important to understand how community nurses manage ethical conflicts to make recommendations about needed supports. It is also critical to understand how community nurses manage ethical conflicts because unresolved conflicts may result in negative ramifications for nurses, for organizations, and for clients.

In recent years, researchers in Japan, South Korea, and Norway have investigated ethical conflicts during community-based care delivery (Asahara et al., 2013; Choe et al., 2015; Dahl et al., 2014; Lillemoen & Pedersen, 2015). Greenway and colleagues (2013) explored the ethical tensions experienced by home care nurses who attempted to promote preventive care, and Karlsson and colleagues (2013) used a hermeneutic phenomenologic approach to understand the experiences of home care nurses who encountered ethical conflicts when providing end-of-life care. While it is evident that we are beginning to see some research on the ethical conflicts facing community nurses, we are not aware of a published report in Canada outlining how exactly community nurses go about managing conflicts. Therefore, we conducted a research study as a first step in addressing this gap. Our research question was What is the process of behaviors enacted by community nurses when experiencing ethical conflicts in their practice?

Research Design

Grounded theory methodology (Glaser, 1978, 1998), an inductive qualitative research approach that enables researchers to theorize how participants respond to and negotiate meaningful events, situations and circumstances in their natural settings, was employed to explain how community nurses manage ethical conflicts. We chose grounded theory methodology given the research focus was the process of conflict management (i.e., process of behaviors enacted in response to ethical conflict).

Participants and Research Context

Our study focused on registered nurses who provide health care in community settings and who had experienced an ethical conflict. In Canada, community nurses are designated as home care nurses and public health nurses (CNA, 2017b). The research coordinator contacted community health unit managers about the study and received permission to put up recruitment posters. Interested nurses contacted the research coordinator directly by telephone or left their first name and contact information with the community health unit. We recruited according to inclusion criteria that they speak, read, and write English fluently; maintain current professional registration; are directly involved in community-based care; and have had more than 1 year experience working in the community. Twenty-four community nurses (11 home care nurses and 13 public health nurses) comprised our purposive sample. Participants had between 1.5 and 30 years of experience providing community-based care. The age of participants ranged from 23 to 57 years; 23 identified as female and 1 identified as male. Participants were given a gift certificate of US$20 as a token of appreciation for their time. Theoretical sampling included conversations with two professionals from outside the health care sector—one from social work and one from pharmacy.

Data Collection and Analysis

The 24 community nurses were invited to participate in one 60- to 90-min semi-structured face-to-face or telephone interview. As participants in our purposive sample, they were asked to share their ethical conflict experiences with exclusive focus on how they managed conflicts. Research interviews were conducted in offices, on the university campus, or over the telephone. The interview guide included questions such as “Please tell me about an ethical conflict that you have experienced while working as a community nurse” and “What did you do to manage this conflict?” Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Theoretical sampling included talking to professionals from other sectors (i.e., pharmacy and social work) and consulting the ethics literature.

Consistent with grounded theory methodology, we carried out two steps: (a) substantive coding and (b) theoretical coding (Glaser, 1978). Substantive coding entailed open coding and selective coding procedures. During the open-coding procedure, we fractured transcribed interview data into analytic segments that could be raised to an abstract conceptual level by extracting words from the participants’ language (called “in vivo codes”) that depicted relevant ideas, behaviors, or perspectives pertaining to ethical conflicts. Then similar in vivo codes were grouped together into conceptual categories and temporary labels assigned to each grouping. Subsequently, by using the constant comparative method, in vivo codes were compared with one another and with emerging conceptual categories assembled from new incoming data.

Glaserian grounded theory requires that the researcher determines the chief concern or problem facing participants and then the process of behaviors or actions taken to resolve the problem (Glaser, 1978). In our study, following open coding, we sought to identify the main concern of community nurses when confronted by ethical conflicts. We discovered that participants question the legitimacy of their thinking; that is, they need to seek validation that the situation they have identified is actually an ethical conflict that warrants attention. By implementing selective coding, we were able to identify this recurring concern associated with conflict management as well as the basic social psychological processes implemented for resolution which became the basis for the theoretical model. All emerging conceptual categories were selected relevant to this recurring concern around which generation of the theoretical model occurred that explains how ethical conflicts are managed.

It was during the second step of analysis (theoretical coding) that we expanded emerging conceptual categories and assembled them theoretically by using Glaser’s (1978) families of theoretical codes (e.g., causes, contexts and consequences) as analytic strategies to enhance abstraction. Theoretical sampling enabled us to further enrich conceptual categories and associated properties. Theoretical sampling included extensive immersion in the ethics literature and selection of comparative data—a pharmacist and a social worker explained how they managed ethical conflict.

Ethical Considerations

The study was granted approval by the Health Research Ethics Authority of Newfoundland and Labrador and by provincial health authorities. Ethical considerations included participant imposition, discomfort, confidentiality, and freedom to withdraw. We emphasized with participants that protection of their interests and well-being took precedence. We obtained written consent for audiotaping interview sessions after describing measures being taken to ensure confidentiality and anonymity. All participants were fully aware of their freedom to withdraw at any point without fear of reprisal.

Rigor

Criteria for demonstrating rigor included fit, relevance, work, and modifiability, as developed by the co-originators (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) and later adapted by Glaser (1978). We fulfilled the criterion of emergent fit by ensuring that we did not force data to fit predetermined ideas; rather, we enabled emergence of the main concern and conceptual categories. And according to Glaser and Strauss (1967), if a theory is to work, it should be relevant and contextualized to a particular substantive area. This was evidenced by how we formulated our theoretical model (Moral Compassing) to explain how community nurses manage ethical conflicts by drawing from everyday practice realities of community nurses and by cross-checking emerging concepts and processes against perceptions of subsequent interview participants. Finally, Moral Compassing was generated through what Glaser describes as a “modifying process” (Glaser, 1978, p. 5). We were open and flexible and had to rework our assumptions based on incoming data several times, leading to significant modifications of the basic social psychological processes constituting Moral Compassing (e.g., undergoing a visceral reaction, self-talk, and seeking validation were processes that underwent considerable deliberation).

Findings

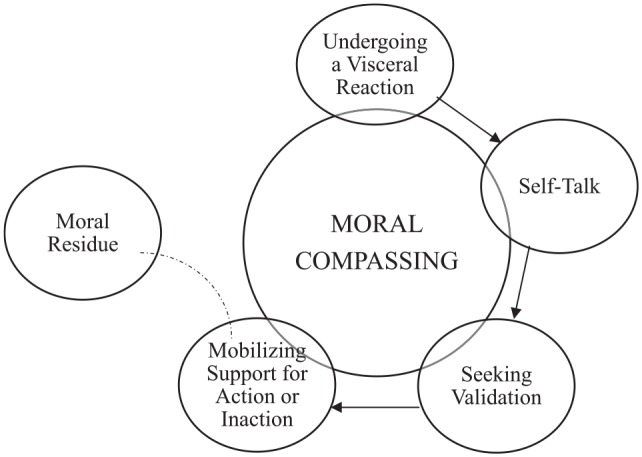

Emerging from our study is an explanatory theoretical model that we named Moral Compassing (Figure 1) and that comprises several processes. The processes are undergoing a visceral reaction, self-talk, seeking validation, and mobilizing support for action or inaction. We also discovered that community nurses may experience continuing distress that we labeled moral residue. Moore and Gino (2013) define moral compass as a metaphorical description of an individual’s orientation to what is right and what is wrong which motivates an individual to make ethically sound judgments and to act accordingly. We applied the term “moral compassing” to explain how community nurses navigate through moral uncertainty and decide whether they will act and what action they will take. First (during undergoing a visceral reaction), they know at a gut level that something is wrong and quality care is not being provided. Then, they enact the rational thinking process of self-talk to convince themselves that their Code’s nursing values and ethical responsibilities have been violated, and hence, a real ethical conflict exists (i.e., their sense of uneasiness stems not from personal values but from professional values). Once confident, they enter into the process of seeking validation to seek confirmation through disclosure and open dialogue with their co-workers. They rely on their co-workers to verify that the facts are correct and that they are dealing with a valid moral concern. Once they are certain that they are facing an ethical conflict that warrants action, they seek options during the process of mobilizing support for action or inaction.

Figure 1.

Community nurses manage ethical conflicts through Moral Compassing which comprised processes beginning with undergoing a visceral reaction, then self-talk, then seeking validation, then, finally, mobilizing support for action or inaction. Moral residue is the aftermath that is experienced by some community nurses.

Overall, Moral Compassing (Figure 1) fortifies a sense of moral agency, and community nurses are able to approach managers and, or, consult with ethics committees. However, some nurses described what we have identified as moral residue which is the continuing distress some community nurses experience, especially when conflicts are not fully resolved, that can manifest in lingering psychological distress for months and even years later.

Undergoing a Visceral Reaction

Moral Compassing (Figure 1) begins with awareness that something is not right originating deep within the subconscious mind of the community nurse. Participants described a “discrepancy” between their “morals” and “beliefs” and a situation or institutional policy. An instinctive feeling, an uneasiness that nurses describe as a “gut feeling,” arises that causes them to pause and consequently their work is disrupted. One nurse stated, “My intuition is telling me there is more to this.” This intuitive knowing is brought to their attention as feelings or sensations and could be, as one participant described, “the kind of read I get on situations and people—that’s how I tend to approach ethical dilemmas. It’s what I’m sensing.” While the nurses acknowledge being well aware of ethical principles of “do no harm” and promote client “autonomy,” nurses also spoke of using their intuition. One participant stated that, “there’s a lot of logic there but for me it’s more intuitive, it’s more a feeling.” Participants in our study described reacting with intense feelings and strong emotions. For example, some shared becoming “really frustrated” and being “stressed about it at home.” The source of their intense reaction is their inability to achieve quality care delivery. They expressed feelings of doubt, guilt, and anxiety. This visceral agitation that something is wrong leads to the process of self-talk.

Self-Talk

While undergoing a visceral reaction is the intuitive “catalyst” that something is not right, self-talk is the ensuing rational thinking process during which “logical steps” are set in motion. During self-talk, nurses mull things over in their minds as they carry out an internal dialogue. The first stage of this process is ensuring that the conflict is real—nurses question whether an ethical conflict or moral problem is truly the source of their visceral agitation.

Nurses reflect, pondering why they “feel a certain way”:

A lot of times I find I do a lot of self-reflection just because, particularly with the emotional part of it—just because I might be feeling emotions as a result it may not necessarily be because of the ethical dilemma itself. It could just be buttons were pushed that something happened to me when I was a teenager that is similar . . . So that ability to kind of step away and look and see.

One participant explained that self-talk refers to clarifying personal values from professional mandates:

So it’s all those issues and much of it comes to values clarification and I think that’s what helps with the ethical conflicts with it because at the end of the day while nurses may have their own personal values around immunization or breastfeeding or around self-determination and all of those things, they must espouse what the program, you know what the organization presents. And you know they must be able to do that convincingly with clients or else they need to look at working elsewhere, you know where their values line up.

It was apparent that the antecedent to the process of self-talk is the nurse’s professional practice desire for client-centered care. Participants described self-talk as “soul-searching,” examining if their practice was adequate to meet client needs. Self-talk consists of asking “what’s best for the client?” It is not entirely evident to some nurses that a program or policy is really intended to assist clients. “Are clients benefitting?” Compelled by “duty” and “responsibility” and motivated by obligation to clients, self-talk continues in an attempt to try to “work through” what seems to be an ethical situation. Nurses then transition from talking with self to talking it out with coworkers.

Seeking Validation

During the process of seeking validation, nurses seek confirmation that they are actually encountering an ethical situation by discussing their intuitive feelings with coworkers. One participant asked her coworkers, “Would you feel bad if you were in this scenario?” And, “This just doesn’t feel right to me. Am I reading this wrong? Am I reading this right? What do you think? What’s your interpretation of this?” Another participant added, “Like am I too close to the situation? Am I not close enough?” Perhaps objectivity is uncertain as alluded to in our study; that is, nurses present the situation “as they see” it, present the “facts as they know” them, and, although nurses may be “fairly pragmatic and insightful” we were told, they recognized that feelings and emotions could be clouding their judgment.

Seeking validation also offers nurses a mechanism to ensure their facts are correct. Nurses told us they need validation that they are “extrapolating the correct information” to assess the situation as part of their information gathering strategy: “Being able to talk to colleagues is really helpful because that helps you validate your concerns or give you another perspective on it.” Nurses require a full understanding of the situation to deal with it appropriately. They were mindful when questioning policies that were historically enacted for specific reasons. Seeking validation avoided risk-taking that may unintentionally negatively impact the client.

Nurses debrief with each other as a form of catharsis in the midst of the dilemma to release emotions. To reduce tension, nurses debrief as a team for informal sessions during break times or at the end of their work day. One of our participants shared that she might say,

‘This is what I’m facing and it’s really frustrating,’ and they either provide me with some solutions or advice or they kind of just let me talk it out and acknowledge that I am frustrated and yet I can’t do anything about it. So I find that helps to let the other nurses know that you’re going through that with your clients because you can’t express a lot of emotions in front of the client and in front of their family members so to go back to the office and express it helps a lot.

The consequences of seeking validation is sustained mental well-being because the process addresses nurses’ needs to know they are on the right track and that they have identified a valid moral concern that merits acknowledgment and discussion.

Mobilizing Support for Action or Inaction

Now knowing that they are indeed encountering an ethical situation, nurses find support for their decision to take action or to “let it go” and “move on” during this process of mobilizing support for action or inaction. Nurses in consultation with coworkers “will try to weigh the consequences of their actions.” It may mean asking, “I have this or that client in this and that situation, what should I do?” The nurse wants assistance appraising all possible options so that the best route is chosen. One participant explained, “I’ll process it myself and say, ‘Yeah maybe that’s a good route for me to take.’ I’ll look to others to give me the various paths I could take and say, ‘Okay, that route will work for me.’”

Support from coworkers in their decision-making provides nurses with the moral agency to bring forward ethical conflicts with their managers. Participants in our study spoke highly of their managers in terms of the level of support offered. Part of bringing forward issues with management during this process is clarifying professional legal obligations and implications. Moral agency is defined by Jacobs (2001) as a particular trait possessed by an individual that is manifest in the individual’s ability to reason, self-determine, and act morally. Moral agency, we discovered, is enhanced when nurses can reason from a solid understanding of their legal obligations and after they have thoroughly reviewed their scope of responsibilities and potential impacts. Nurses, however, cautioned that

you don’t want to be the one that is going to bring a good program down because you did something that you thought was the right thing do at the time. So it’s always good, even though you might think this is definitely the right thing to do, it is always good to take things to your manager or your immediate boss.

Clarifying policies also promotes moral agency.

Nurses want to know the policies, the rules, and their roles and responsibilities and what they “have to do” to ensure they are taking the right actions:

It seems like all my ethical issues that I have had, I’ve kind of tried to resolve them amongst my coworkers and my manager and my clinical coordinator. We’ve kind of come to a solution by policy and what should be done, and, you know, we’ve come, I guess, to a solution to some extent.

To safeguard client care, nurses may be forced to undermine restrictive administrative policies:

I’d give the cancer client their drug and I’d get the doctor’s order—if I couldn’t get it that day I’d get it. But that’s where ethically I say, you know what, the right thing for me to do here is do this. It’s not the right thing according to [name of health authority] and the policies that I’m supposed to follow . . .

Depending on the severity of the ethical situation, nurses might decide to take concerns to professional practice consultations—the team lead, a colleague or another manager—whoever could resolve the situation as quickly as possible. Others bring the more serious issues to the ethics committee for consultation or some nurses felt the ethics committee and opportunities for consultation were inaccessible, a somewhat remote entity.

After bringing issues forward to management, what generally follows are team meetings, case conferences, and consultations that serve as mechanisms to address ethical issues. Generally, managers will consult with executive level administrators or consult with ethics committees. Voiced by participants is their frustration not knowing, sometimes, the outcomes of their proposed actions, “I attended the ethics consult and I presented the issue and it was determined that, ‘yes, this is an ethical issue’ but then I don’t know where it went from there.” Some ethical conflicts are managed through inaction, as one participant explained,

Umm, nobody wants to be the one that’s always complaining about something, so for the most part, you know, you ask yourself before you get on that bus, is this a battle I want to fight? How important is it to me? If it’s not that significant I’ll just put up and shut up, but if it gets to the point that something is, you know, you really think this is impacting quality of care [I have to act] . . .

Nurses are confident in their decision for inaction when they accept that in time issues will resolve or issues are out of their control:

I guess internally I just had to tell myself that was for the best that you know, that hopefully the whole situation you know would improve . . . I kind of had to just distance myself from it you know and just separate, “Okay, this is work” and you do what you got to do at work and you kind of have to separate yourself from that.

Sometimes, there is no viable course of action to address an ethical conflict. For example, with families, the nurse “can talk with the family and explain things but there is no standard approach [exists] to resolve it.” There is “no way” you can solve “all” the problems. When inaction is the only option, managerial support is critical to mitigating negative emotions or moral distress. Moral distress is a term describing an inability to act on a moral judgment (Morley et al., 2019):

. . . I find sometimes even after I’ve talked it out with my fellow nurses, it helps to go to the manager and say, ‘this is what I’m facing. I’m feeling uncomfortable in the situation or I’m feeling frustrated. I don’t see any options personally, but I wanted you to know that this is happening and I’m not totally comfortable with the care I’m providing,’ and I find that it helps for the manager to know and she’ll talk me through it a lot and provide some support, and I think just validate my decisions . . .

When attempts to address an ethical conflict cease either through inaction or action, nurses often experience lingering feelings of regret or remorse especially after having faced particularly disturbing ethical situations. If ethical issues remain unresolved or if they were not adequately addressed to the satisfaction of the nurse or client, psychological suffering may linger for an extended period of time which is referred to in the literature as “moral residue” (Webster & Baylis, 2000, p. 208). We found evidence of such in the accounts of ethical conflict disclosed in our study. Participant descriptions of current and past experiences with ethical conflicts clearly revealed that they held residual feelings; that is, moral distress continued to be manifest months, years, and even decades later, to which we have assigned the label, “moral residue.”

Moral Residue

Moral residue is “that which each of us carries from those times in our lives when in the face of moral distress we have seriously compromised ourselves or allowed ourselves to be compromised” (Webster & Baylis, 2000, p. 208). We propose that moral residue is, for some, the aftermath of Moral Compassing (Figure 1). As nurses described ethical conflicts they had encountered in community health practice settings, some also recounted enduring emotions associated with those experiences that several authors have defined as “moral distress” (Morley et al., 2019). One participant lamented about the “angst and upset,” the emotions and feelings that have not “really quite gone away.” Another nurse shared, “I’ve never forgotten that [ethical conflict]. Experiences like that, you bring with you, and you reflect back you know no matter how long ago it was.” Often they seemed surprised at the degree of emotion that still resonated as they described their ethical situations. Moral residue can also cause nurses to ponder and reflect on their choice of career paths, especially when they continue to be constrained by institutional policies and regulations and believe their “hands are tied” and that they are powerless to make change:

I still do what I’m supposed to do but I don’t feel good about it . . . I feel like maybe I shouldn’t be a public health nurse because this is what we do and maybe if I don’t feel good about it maybe I shouldn’t be doing this kind of work. I’ve never really felt good about it.

Discussion

This study is one of the first to examine how nurses manage ethical conflicts when delivering health care in community settings. We identified that moral uncertainty is the core concern when community nurses are attempting to address what they perceive is an ethical issue. Participants told us that they struggle to figure out if they are actually being confronted by a problem of right or wrong, and if so, what is the right course of moral action to pursue. Wurzbach (2015) describes moral uncertainty as the tug of war that occurs when one has two equally viable courses of action but there are too many ambiguities to know with certainty which course of action is the right choice. Essentially, in our study, community nurses described a tug of war that they experience at the outset. Prior to initiating any form of ethical decision-making process, they struggled to determine “Am I witnessing something that is morally wrong and is it substantial enough that I should act on it?” We adopted the term “moral uncertainty” to describe their struggle.

Immersion in the ethics literature caused us to reflect on the role of moral development and moral standards. Nursing practice, some may argue, is the “moral imperative to act justly” (Stephany & Majkowski, 2012, p. 3)—a value and responsibility to which the community nurses in our study were determined to uphold. We discovered nurses in our study aspire to act according to moral values and moral obligations embedded in their code of ethics. Nurses may well be the health care providers who internationally carry a reputation for possessing one of the highest levels of moral sensibilities (Ranjbar et al., 2017) that according to Rest (1994) equips nurses to recognize and respond to moral issues.

It is interesting to note that moral compassing is also a term that was adopted by Storch and colleagues (2002) to describe the mandate of nurse leaders, contending that it is the moral responsibility of nurse leaders to advocate for quality practice environments to ensure nurses at the bedside continue to provide ethical care (p. 7). By doing so, nurse leaders are fulfilling their mandate to be the moral compass to which all nurses can consult for guidance and direction in their practice. “Nurse leaders needed to be the moral compass for nurses, using their power as a positive force to promote, provide and sustain quality practice environments for safe, competent and ethical practice” (Storch et al., 2002, p. 7). Similarly, moral compass was a term embraced by Mannix et al. (2015), more than a decade later, to highlight the critical importance of aesthetic leadership with its explicit moral dimension as a strategy to achieve positive organizational outcomes in health care.

Participants shared that they could depend on their managers to serve as a strong moral compass and to nurture their moral agency that arises from their commitment to act justly and to pursue the delivery of quality care. Participants also spoke highly of the support available from management, enabling them to simply “let off steam” and, or, to assume responsibility for ensuring ethical issues are addressed. Storch and colleagues (2002) emphasized the critical role of managerial support, not only at the time of an ethical event but as a constant in the workplace environment; that is, nurses should already know that their opinions matter and that their perspectives are valued. Ethicists (Pavlish et al., 2014) inform that if health care providers (i.e., referring to acute care settings) show mutual respect for one another and are willing to listen and engage in dialogue, then the workplace can serve as an ethically sensitive and responsive environment—something that was made explicit in our study.

In the extant literature, several authors discuss silence (e.g., Greenberg & Edwards, 2000) as a type of conflict management strategy. Although most study participants chose to speak up because they wanted to advocate for their clients, there were some who disclosed how they feared reprisal and chose not to voice their ethical concerns and “rock the boat” and cause problems. Some participants stated that they chose not to bring attention to something as a form of strategic silence. Van Dyne et al. (2003) described this form of silence as “defensive silence.” We can surmise, then, that community nurses who are more risk-averse may make a conscious decision to use defensive silence and withhold their perspectives to protect themselves. Participants in our study who spoke up did so with what is deemed “other-oriented” behavior and a “prosocial voice” because the goal was to help others regardless of reprisal, and possibly, there was less focus on self (Van Dyne et al., 2003).

Limitations

It is important to note that this study has several limitations. The community nurses who were interviewed by telephone may not have developed the same rapport with the interviewer; however, we did not notice that they spoke less. As well, this study did not examine how nurses’ tenure in the profession may influence how they manage ethical conflicts; how nurses decide an issue is an ethical one; or, how nurses actualize their moral agency and avoid moral distress and residue—all are interesting areas for future research. Community nurses placed major emphasis on talking with colleagues as they navigated ethical issues and this leads to speculation that the moral identities of nurses may be dialogical. We encourage other researchers to explore the dialogical nature of how nurses identify, manage, and act during ethical conflict.

Conclusion

Moral Compassing (Figure 1) entails several sequential processes that community nurses enact when challenged with ethical conflicts in their practice. Undergoing a visceral reaction, self-talk, seeking validation, and mobilizing support for action or inaction resolve, primarily, a state of moral uncertainty and together the processes comprise the Moral Compassing model explaining how community nurses manage ethical conflicts. For some community nurses, moral residue was a very real phenomenon, and moral distress may take its toll if left unaddressed. If moral distress is compounded by staff shortages, fiscal cutbacks, complex caseloads, and other stressful factors in the community practice environment, we may witness burnout, absenteeism, leaving the profession, and other negative impacts on work life and careers.

Drawing from our model, a community nurse must first recognize that an ethical situation does indeed exist which can be challenging in a climate of fiscal restraint necessitating efficiency, shortened client visits, and having to work with fewer staff and resources. Moreover, recognition of moral or ethical concerns and discussing ethical decision-making may not be the cultural norms of the workplace or organization. Nurses in our study expressed stress, anxiety, guilt, and frustration when dealing with ethical conflicts that were buffered and reduced, largely, by peer and managerial support. We recommend in addition to ample opportunity for peer debriefing and disclosure and deliberation with managers that nurses are offered professional development training that enhances affective coping along with ethics decision-making skills. Other strategies can include continuing ethics education and establishment of an ethics committee tailored to community nurses and the local workplace context.

Values clarification is also pivotal to overcoming moral uncertainty and developing the requisite moral agency to take decisive action. Nurses in our study felt compelled to take pause to clarify personal moral values from their professional mandate. Thorough orientation for new hires and ongoing review of codes and standards of practice and organizational values and expectations are recommended.

Author Biographies

Caroline Porr is an associate professor in the Faculty of Nursing, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Alice Gaudine is a professor and Dean of the Faculty of Nursing, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Kevin Woo is an associate professor in the School of Nursing, Queen’s University.

Joanne Smith-Young is the Nursing Research Unit Coordinator in the Faculty of Nursing, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Candace Green is a Memorial’s Undergraduate Career Experience Program student.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Caroline Porr  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0887-2116

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0887-2116

References

- Asahara K., Ono W., Kobayashi M., Omori J., Momose Y., Todome H., Konishi E. (2013). Ethical issues in practice: A survey of home-visiting nurses in Japan. Japan Journal of Nursing Science, 10(1), 98–108. 10.1111/j.1742-7924.2012.00216.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Nurses Association. (2017. a). Code of ethics for registered nurses (2017 ed.). https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/code-of-ethics-2017-edition-secure-interactive [PubMed]

- Canadian Nurses Association. (2017. b). Community health nurses of Canada (CHNC). https://cna-aiic.ca/en/professional-development/canadian-network-of-nursing-specialties/whats-new-with-the-network/network-news-room/member-profiles/2014/chnc-member-profile

- Carnevale F. A. (2013). Confronting moral distress in nursing: Recognizing nurses as moral agents. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 66, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe K., Kim K., Lee K. S. (2015). Ethical concerns of visiting nurses caring for older people in the community. Nursing Ethics, 22(6), 700–710. 10.1177/0969733014542676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl B. M., Clancy A., Andrews T. (2014). The meaning of ethically charged encounters and their possible influence on professional identity in Norwegian public health nursing: A phenomenological hermeneutic study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28(3), 600–608. 10.1111/scs.12089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry-Revere S. (1992). The accountability of bioethics committees and consultants. University Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudine A., Beaton M. R. (2002). Employed to go against one’s values: Nurse managers’ accounts of ethical conflict with their organizations. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research, 34(2), 17–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudine A., LeFort S. M., Lamb M., Thorne L. (2011. a). Clinical ethical conflicts of nurses and physicians. Nursing Ethics, 18(1), 9–19. 10.1177/0969733010385532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudine A., LeFort S. M., Lamb M., Thorne L. (2011. b). Ethical conflicts with hospitals: The perspectives of nurses and physicians. Nursing Ethics, 18(6), 756–766. https://doi.org/1177/0969733011401121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudine A., Thorne L. (2012). Nurses’ ethical conflict with hospitals: A longitudinal study of outcomes. Nursing Ethics, 19(6), 727–737. 10.1177/0969733011421626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudine A., Thorne L., LeFort S. M., Lamb M. (2010). Evolution of hospital clinical ethics committees in Canada. Journal of Medical Ethics, 36(3), 132–137. 10.1136/jme.2009.032607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G. (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussion. Sociology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B. G., Strauss A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg J., Edwards M. S. (2000). Voice and silence in organizations. Emerald Group Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Greenway J. C., Entwistle V. A., terMeulen R. (2013). Ethical tensions associated with the promotion of public health policy in health visiting: A qualitative investigation of health visitors’ views. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 14(2), 200–211. 10.1017/S1463423612000400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs B. B. (2001). Respect for human dignity: A central phenomenon to philosophically unite nursing theory and practice through consilience of knowledge. Advances in Nursing Science, 24(1), 17–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson M., Karlsson C., Barbosa da, Silva A., Berggren I., Soderlund M. (2013). Community nurses’ experiences of ethical problems in end-of-life care in the client’s own home. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 27(4), 831–838. 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01087.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb M., Storch J. L. (2012). A historical perspective on nursing and nursing ethics. In Storch, P. J. L., Rodney, Starzomski R. (Eds.), Toward a moral horizon: Nursing ethics for leadership and practice (2nd ed., pp. 20–40). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Lillemoen L., Pedersen R. (2015). Ethics reflection groups in community health services: An evaluation study. BMC Medical Ethics, 16(1), Article 25. https://bmcmedethics.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/s12910-015-0017-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack C. (2013). When moral uncertainty becomes moral distress. Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics, 3(2), 106–109. 10.1353/nib.2013.0037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magelssen M., Gjerberg E., Pedersen R., Fǿrde R., Lillemoen L. (2016). The Norwegian national project for ethics support in community health and care services. BMC Medical Ethics, 17, Article 70. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2e43/2de1c74fdc61bc2225cb4d4b4e0f118d7ec2.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannix J., Wilkes L., Daly J. (2015). Good ethics and moral standing: A qualitative study of aesthetic leadership in clinical nursing practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(11–12), 1603–1610. 10.1111/jocn.12761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C., Gino F. (2013). Ethically adrift: How others pull our moral compass from true North, and how we can fix it. Research in Organizational Behavior, 33, 53–77. [Google Scholar]

- Morley G., Ives J., Bradbury-Jones C., Irvine F. (2019). What is “moral distress?” A narrative synthesis of the literature. Nursing Ethics, 26(3), 646–662. 10.1177/0969733017724354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlish C., Brown-Saltzman K., Jakel P., Fine A. (2014). The nature of ethical conflicts and the meaning of moral community in oncology practice. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(2), 130–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine E., Hayes K. (2005). The need for a clinical ethics service and its goals in a community healthcare service centre: A survey. Journal of Medical Ethics, 32(10), 564–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjbar H., Joolaee S., Vedadhir A., Abbaszadeh A., Bernstein C. (2017). Becoming a nurse as a moral journey: A constructivist grounded theory. Nursing Ethics, 24, 583–597. 10.1177/0969733015620940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rest J. (1994). Background theory and research. In Rest J., Narvaez D. (Eds.), Moral development in the professions: Psychology and applied ethics (pp. 1–26). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Rodney P., Starzomski R. (1993). Constraints on the moral agency of nurses. Canadian Nurse, 89(9), 23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephany K., Majkowski P. (2012). The ethic of care: Our moral compass. In Stephany K. (Ed.), The ethic of care: A moral compass for Canadian nursing practice (Vol. 17, pp. 3–19). 10.2174/97816080530491120101 [DOI]

- Storch J. L., Rodney P., Pauly B., Brown H., Starzomski R. (2002). Listening to nurses’ moral voices: Building a quality health care environment. Canadian Journal of Nursing Leadership, 15(4), 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyne L., Ang S., Botero I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359–1392. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.389.9025&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Google Scholar]

- Webster G., Baylis F. (2000). Moral residue. In Rubin S. B., Zoloth L. (Eds.), Margin of error: The ethics of mistakes in the practice of medicine (pp. 327–332). University Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Wurzbach M. E. (2015). Experiencing moral uncertainty in practice. Virginia Henderson Global Nursing e-Repository; https://sigma.nursingrepository.org/handle/10755/581749 [Google Scholar]

- Yarling R. R., McElmurry B. J. (1986). The moral foundation of nursing. Advanced Nursing Science, 8(2), 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]