Abstract

Sugar detection is important for many applications. New developments in sugar signaling would provide new technologies to monitor glucose and other sugars. Azo dye 1 presents a new way to build molecular color sensors for monosaccharides. The boronic acid group is used as chelator group for monosaccharides and linked directly in resonance with the aromatic dye. Dye 1 shows a color change, from orange to purple, in the presence of sugar at neutral pH.

Grahical Abstract

The use of the boronic acids as chelator groups for monosaccharides has attracted increasing attention for the development of alternative approaches in sugar signaling. To date, glucose recognition and detection are mostly limited to enzymatic assays.1,2 Some characteristics of enzymes, such as stability, heat and solvent resistance, destruction of the analyte, etc., have limited their use as sensors for sugars. The development of synthetic probes is expected to overcome some of these problems and provide new technologies for sugar detection.

Numerous fluorescent probes for monosaccharides based on boronic acids have been described in the literature.3–5 The most promising probes are based on two mechanisms. The first one uses the acid–base interaction between the boron group and an amino group to induce spectral changes on a fluorophore based on photoinduced electron transfer.4 The second one uses the difference between the electron-withdrawing and electron-donating properties of the boronic group to induce spectral changes on a fluorophore based on a charge transfer in the excited state.5

Acid–base interaction between phenylboronic acid and amino groups has also been used for the development of molecular color sensors for monosacharides.6–8 In this case, the interaction between the boron group and the amino group modifies the intramolecular charge transfer property of the dye and induces a color change. Diphenyl azo dyes have been used in these studies. To our knowledge, only one color sensor for saccharides, not based on an azo dye, has been reported in the literature.9 In this case, large color changes were observed only for phosphate and other derivatives of saccharides. Small changes were obtained in the presence of fructose and glucose.

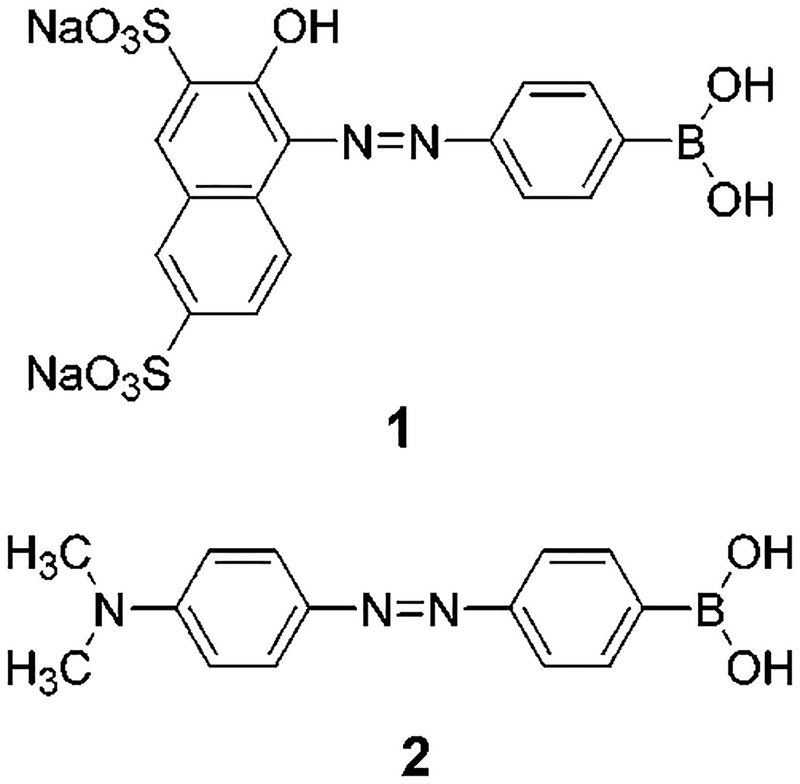

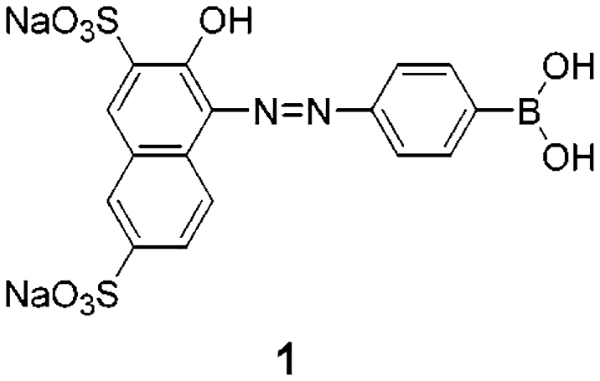

In this Letter, we report the synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of new azo dyes (Figure 1) having a boronic acid group in resonance with the aromatic ring of the dyes. In this case, we investigated the effect of the change of the electronic properties of the boronic acid group between its neutral (without sugar) and anionic (in the presence of sugar) forms on the absorption spectrum (color) of the dye.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of the investigated dyes.

1-(4-Boronophenylazo)-2-hydroxy-3,6-naphthalenedisul-fonic acid disodium salt (1) and 4-[4-(dimethylamino)-phenylazo]benzeneboronic acid (2) were synthesized in a one-pot reaction from the commercially available 4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)aniline (Aldrich) and 2-naphthol-3,6-disulfonic acid disodium salt, for 1, and N,N-dimethylaniline, for 2. In a first step, the diazonium ion of the aniline boronic acid derivative was generated with sodium nitrite in HCl; the diazonium ion was then coupled by nucleophilic substitution with the corresponding substrate. Synthetic details and characterization data can be found in the Supporting Information section.

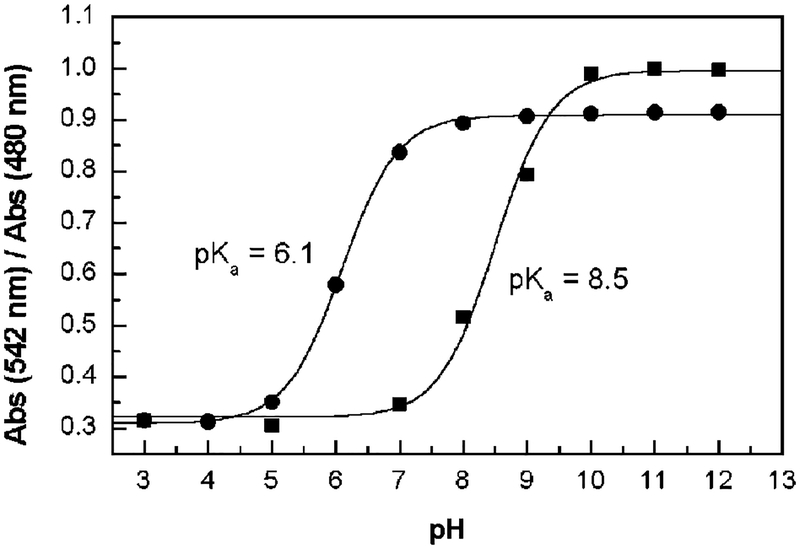

In water, dye 1 shows an orange solution with a maximum in the absorption spectrum of 495 nm (∈ = 22 950 M−1 cm−1). As the pH increases from 3 to 12, we observed a color change from orange to purple associated with a red shifting of the absorption band with an isobestic point at 515 nm. The corresponding titration curve is displayed in Figure 2. pH titration in the presence of d-fructose (fructose was chosen because it shows the highest association constant with monophenylboronic acid in comparison with those of other sugars1) results in spectral changes similar to those in the absence of sugar, but the color change is shifted to a lower pH, Figure 2. Spectral changes, observed as the pH increases, are associated with the formation of the anionic form of the boronic acid. The boronic acid group is an electron-deficient Lewis acid having an sp2-hybridized boron atom and a triangular conformation. The anionic form of the boronic acid group is characterized by a more electron rich sp3-boron atom with a tetrahedral geometry.10 The change in the electronic properties of the boronic group as the anionic form is formed are at the origin of the spectral changes observed. The pKa of 8.5 is typical for the monophenylboronic acid as well as the increase in the acidity of the complex boronic group:sugar, pKa of 6.1.5,11 This large decrease in the pKa of the complexed in comparison with that of the uncomplexed boronic group allows the detection of sugar at neutral pH, where the maximum optical changes are observed.

Figure 2.

Titration curves against the pH in the absence (■) and in the presence (●) of d-fructose, 50 mM, for 1 (4.92 × 10−6 M). Measured in buffer solutions at room temperature.

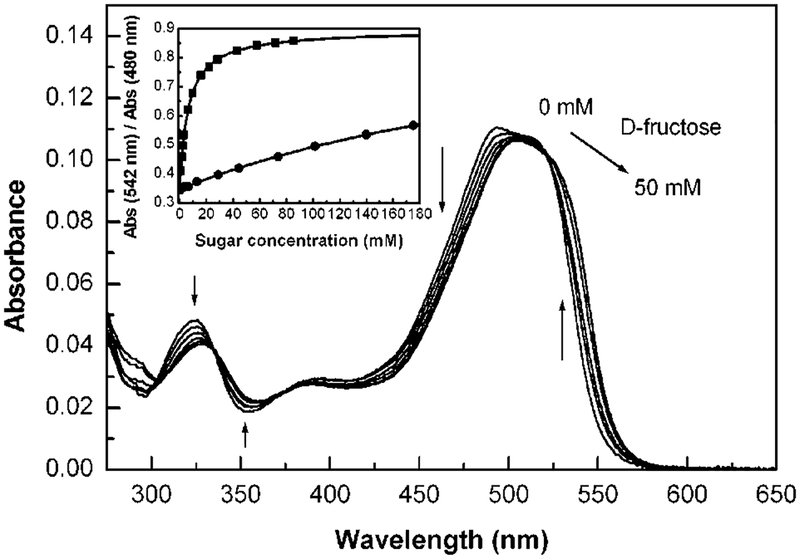

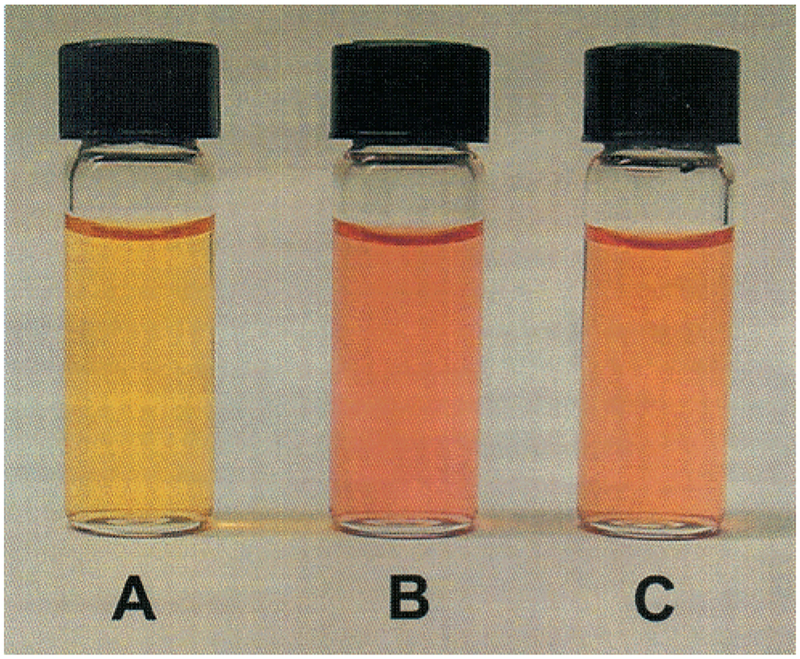

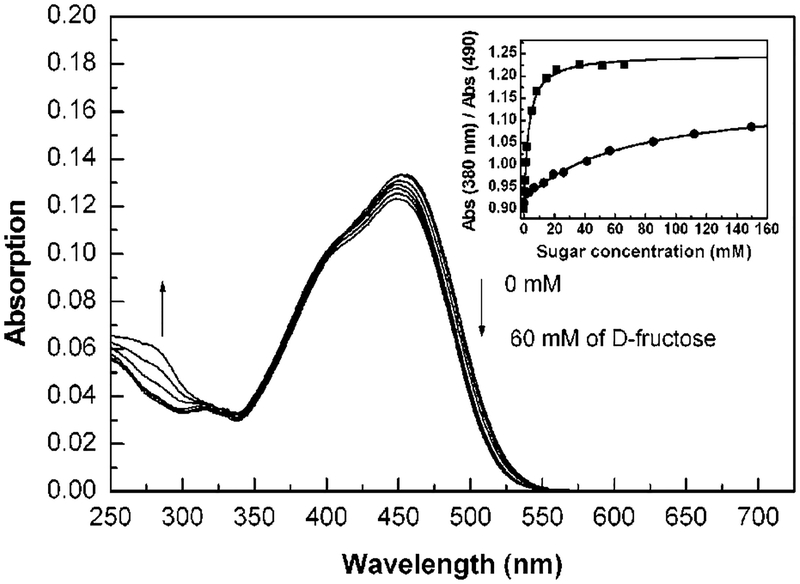

Spectral changes induced by the presence of sugars are shown in Figure 3 with d-fructose. We observed the same changes as previously described for the pH effect, i.e., red shift in the absorption band. This shift is relatively small, but gives enough color change to be detected visually. Actual solutions of dye 1 in the absence and presence of sugars (d-fructose and d-glucose) are displayed in Figure 4. In the absence of sugar, the probe shows an orange solution, while in the presence of sugar the solution shows a more purple-reddish color. Color changes were obtained immediately after the addition of sugar, at room temperature. Titration curves against d-fructose and d-glucose are shown in the inset of Figure 3. The probe 1 shows a dissociation constant (Kd) of 6.3 mM for d-fructose and 370 mM for d-glucose. As mentioned above, a higher affinity for d-fructose is a general observation for monoboronic acid derivatives. Probe 1 could be useful for qualitative visual detection of sugars. Concentrations of 5–10 mM of d-fructose can be easily detected in solution even in the presence of a few millimoles of glucose.

Figure 3.

Effect of d-fructose on the absorption spectrum of 1 (4.92 × 10−6 M). Measured in phosphate buffer (200 mM), pH 7.0, at room temperature. Inset: titration curves against sugars, (■) d-fructose, (●) d-glucose.

Figure 4.

Solutions of 1 in phosphate buffer (200 mM), pH 7.0, in the absence of sugar (A), in the presence of 100 mmol of d-fructose (B), and in the presence of 250 mmol of d-glucose (C).

Probe 2 shows a yellow solution in water at neutral pH. The absorption spectrum of 2 shows a maximum at 460 nm (∈ = 21 800 M−1 cm−1) which shifts to shorter wavelength at high pH. The effect of the sugar on the absorption spectrum is shown in Figure 5. For this derivative, the optical changes are too small to be detected visually.

Figure 5.

Effect of d-fructose on the absorption spectrum of 2 (1.57 × 10−5 M). Measured in phosphate buffer (200 mM), pH 7.0, at room temperature. Inset: corresponding titration curves against sugars, (■) d-fructose, (●) d-glucose.

In summary, we have shown that the incorporation of the boronic acid group in resonance with an azo dye could lead to a color change of the dye. This color change is expected to be due to the conformational change of the boron atom between its neutral and anionic forms. Despite the change between the electron-withdrawing and electron-donating properties of the boronic group, the effect on the intramolecular charge transfer of the dye is weak. In the case of dye 2, the electronic properties of the dye are governed by the presence of the dimethylamino group and are almost independent of the presence of the electron acceptor boronic group. For example, upon protonation of the dimethylamino group at pH < 2, dye 2 show a drastic color change from pale yellow to deep red in solution. We think probe 1 shows larger optical changes because no strong electron donor group is present on the dye. Work is in progress to investigate the effect of the boronic acid conformational change on the optical properties of a larger diversity of azo dyes to have a better knowledge of the origin of the color change and then to maximize the color change observed.

Acknowledgment.

This work was supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International, 2-2000-546, with partial support from the NIH National Center for Research Resources, RR-08119.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Synthetic details and characterization data for compounds 1 and 2. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- (1).Gough DA; Armour JC Diabetes 1995, 44, 1005–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Heller A Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 1999, 1, 153–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hartley JH; James TD; Ward CJJ Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2000, 19, 3155–3184. [Google Scholar]

- (4).James TD; Sandanayake K; Shinkai S Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl 1996, 35, 1911–1922. [Google Scholar]

- (5).DiCesare N; Lakowicz JR J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 6834–6840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Sandanayake K; Shinkai SJ Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 1994, 1083–1084. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ward CJ; Patel P; Ashton PR; James TDJ Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun 2000, 3, 229–230. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Koumoto K; Shinkai S Chem. Lett 2000, 8, 856–857. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Davis CJ; Lewis PT; McCarroll ME; Read MW; Cueto R; Strongin RM Org. Lett 1999, 1, 331–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Lorand JP; Edwards JO J. Org. Chem 1959, 24, 769–774. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Mizuno T; Fukumatsu T; Takeuchi M; Shinkai S J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 2000, 3, 407–413. [Google Scholar]