Abstract

Background

Patients approaching end-stage renal disease (ESRD) experience a high level of decisional conflict because they are often not provided with sufficient support and information regarding different treatment options prior to renal failure. Decisional conflict is an important correlate of treatment satisfaction, as it is associated with disease- and treatment-related knowledge that can inform decision-making. Patient activation, the willingness and ability to independently manage one’s own health and healthcare, is an individual difference factor that may have important mitigating effects on decisional conflict.

Purpose

To identify modifiable factors that may enhance the decision-making process in patients approaching ESRD by exploring potential mediational effects between decisional conflict, treatment satisfaction, and patient activation.

Methods

Sixty-four patients approaching ESRD completed self-report measures (32% response rate). Measures included the Decisional Conflict Scale, the Kidney Disease Treatment Questionnaire, and the Patient Activation Measure Short Form.

Results

There was a high level of self-reported decisional conflict in this sample. Linear regressions revealed main effects among treatment satisfaction, patient activation, and decisional conflict. These variables were entered into PROCESS to assess a mediational pattern. Results showed that higher chronic kidney disease-related treatment satisfaction predicted lower decisional conflict through higher patient activation in a statistical mediational relationship.

Conclusions

While the link between treatment satisfaction and decision-making is well established, these results suggest this relationship might be partially explained by patient activation, a potentially modifiable process in patients approaching ESRD. Therefore, interventions that encourage patients to become actively involved in their care could also reduce decisional conflict among patients approaching ESRD.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Treatment decision-making, Decisional conflict, Patient activation, Treatment satisfaction

Patients approaching kidney failure experienced less stress regarding treatment decision-making if they also reported greater patient self-management and were satisfied with their previous kidney-related care.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), generally speaking, reflects a loss in the kidneys’ ability to adequately remove fluid, acids, and toxins from the blood. Most often, CKD is caused by another disease like diabetes, hypertension, and/or glomerulonephritis. As CKD progresses, end-stage renal disease (ESRD) develops. This final stage of CKD (Stage 5) requires patients to undergo some sort of renal replacement therapy to sustain life [1]. Renal replacement therapy options include dialysis (in-center hemodialysis [2], home hemodialysis [3], or peritoneal dialysis [4]) and kidney transplant [5]. In some cases, patients approaching the end stage of the disease opt to forgo life-sustaining renal replacement and opt for a combination of active care and comfort care, often referred to in this context as conservative management [6].

Although some patients go on to receive a kidney transplant, most patients (97%) undergo dialysis at some point in the course of the disease [1]. Dialysis uses an artificial apparatus that filters waste products and toxins from the blood [2, 3, 5]. Approximately 88% of incident cases of ESRD began on hemodialysis [1, 2]. In-center hemodialysis is conducted in a clinical setting three times a week, 3–4 hr at a time, and is administered by nurses and technicians in a highly controlled environment [2]. With home hemodialysis, patients and caregivers play a much more active role, and are responsible for self-administration of dialysis allowing flexibility in treatment administration [3]. Similarly, peritoneal dialysis is self-managed and occurs at home. Peritoneal dialysis can be conducted manually or with a machine after a catheter is surgically inserted into the abdominal cavity. During peritoneal dialysis, the dialysate (i.e., dialysis fluid) enters the catheter, and wastes and toxins migrate out of the blood through the lining of the abdominal cavity into the dialysate to be eliminated later when the fluid is drained out [4].

Choosing to engage in a particular form of dialysis may depend on many factors like the size of patients and/or the quality of their vascular sites or abdominal lining, the presence of any sensory or cognitive deficits that may make self-management difficult, amount of social support available, home environment, and patients’ preferences [4]. Overall, there are many potential benefits to engaging in home-based dialysis methods versus in-center hemodialysis such as greater control over scheduling, reduced time in hospitals, improved survival rates, higher quality of life, and financial savings [3]. However, in-center hemodialysis may be more appropriate for patients who do not have an adequate home environment, or the ability, desire, capacity, or support for self-care, and prefer to depend on the hemodialysis unit staff for care. Some patients may also feel overwhelmed by responsibilities of home-based dialysis methods, or do not want to be a burden to others [3, 7, 8]. Despite the wide range of differences among patients and the potential advantages of home-based treatments, approximately 91% of the ESRD dialysis patients in the USA undergo in-center hemodialysis with the remaining 9% receiving one of the two forms of home dialysis [2, 4].

Conservative management is an alternative for patients with ESRD who elect not to undergo dialysis or transplant. It involves comfort care as well as palliative care, and managing one’s fluid balance, blood pressure, metabolism, diet, and treatment of anemia. Typically, this approach results in the death of a patient in a period of weeks or months [6, 9]. Although quality of life and longevity is greater in patients on dialysis compared to conservative management, these differences tend to lessen in patients who are older and with more comorbidities [10].

Each of these treatment options have their own set of benefits and drawbacks, and these factors vary based on an individual patient’s comorbidities, functional status, values, lifestyle, preferences, and resources [3, 6, 11–13]. This decision is important, because their treatment choice is one they must actively engage in for the rest of their lives. Surprisingly, there is evidence that patients approaching ESRD have generally not been engaged in a shared decision-making process about the various treatment options [11–13]. Therefore, there is a critical need to better understand how to engage patients who are approaching ESRD in the treatment decision-making process.

When patients are tasked with choosing a treatment modality that is right for them, but are not provided with sufficient support and information regarding those options, they experience decision-making difficulty and decision-related stress, otherwise known as decisional conflict [14]. Decisional conflict is the state of uncertainty regarding what course of action to take [14]. It is likely to occur when there are several options available involving many risks and benefits for each [15–17]. Patients who have high decisional conflict are likely to fluctuate between choices, delay decision-making, show distress, and question their own values regarding the decision [18]. Unresolved decisional conflict can lead to undesirable consequences associated with the decision such as dissatisfaction with the treatment choice and potentially lower adherence to the regimen [15, 19]. Because patients approaching ESRD face a complex medical decision, and their decision-making processes are poorly understood in the literature, the present study sought to assess the level of decisional conflict in patients approaching ESRD and to identify factors that may reduce decisional conflict and enhance patient satisfaction with the decision-making process.

Potential Mediators of Decisional Conflict

Patient activation is one individual difference variable that may have important effects on decisional conflict. Patient activation is the willingness and ability to independently manage one’s own health and healthcare, and it is considered to be a modifiable process that can increase over time [20] by, for example, teaching self-management strategies [21–23]. Patients with high activation are likely to self-manage their disease-related symptoms, engage in actions to maintain physical functioning, and engage in behaviors that reduce health-related declines. They are also likely to become more involved in treatment as well as diagnostic choices, collaborate with healthcare providers, select healthcare providers or healthcare centers based on performance or quality, and successfully navigate the healthcare system [24]. High patient activation is especially important for patients with chronic diseases because of the many behaviors they must engage in to manage their own health. Studies have shown that highly activated patients are more likely to have lower cholesterol, reduced rates of depression, reduced emergency department visits, and they are also more likely to utilize screening services and engage in healthier eating and exercise following a cancer diagnosis [20, 25]. While previous studies have suggested ways patients with CKD can become involved in their care, such as by educating them on dialysis options prior to renal failure [11–13, 19], these studies have not assessed patient activation differences explicitly and have not examined the relationship of this variable to decisional outcomes.

Greater patient satisfaction with treatment and care may also be essential for productive treatment-related decision-making [26, 27]. While this relationship is well established in many other patient populations [28], treatment satisfaction in patients approaching ESRD has been understudied [29]. It is unknown, for example, how treatment satisfaction is related to the decision-making process among patients approaching ESRD since many patients with CKD do not know the extent or status of their renal impairment [30], and are not being seen by renal care specialists until the end stage of the disease is reached [1].

Past research has demonstrated the importance of patient satisfaction, the level and quality of patient engagement, and the stress associated with patient decision-making in serious physical illness [20, 25–27]. However, these associations have not been previously examined in a sample of patients approaching ESRD. The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the level of decisional conflict in a sample of patients approaching ESRD, and to examine the expectation that higher CKD-related treatment satisfaction and higher patient activation are related to lower decisional conflict. We also conducted additional analyses that were data-driven and exploratory. First, we explored whether specific treatment preferences were related to CKD-related treatment satisfaction, patient activation, and/or decisional conflict. Second, we examined statistical mediational effects between CKD-related treatment satisfaction, patient activation, and decisional conflict to provide a basis for future clinical intervention.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Participants were eligible for this study if they were 18 years or older, had advanced renal impairment measured by an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of 25 mL/min or lower, and were not yet receiving renal replacement therapy. Patients from the nephrology clinic at University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics were recruited by mail or in-person. Potentially eligible patients were mailed an introductory letter, informed consent document, study survey, and postage-paid envelope. Patients were instructed to call to opt-out of the study. A researcher called all patients who did not opt-out 1 week after the initial mailing to describe the study, review the consent document, and answer questions. Patients who agreed to participate were instructed to return the completed consent document and survey in the provided postage-paid envelope. Patients recruited in-person were approached by a researcher in the waiting area of a class on kidney treatment options, and if consented they returned the completed survey once the class was over. All participants who returned surveys were compensated $5. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Demographics and medical characteristics

Participants provided their age, gender, race, marital status, years of education attained, annual household income, and whether they had diabetes, hypertension, and/or heart disease.

Decisional conflict

Participants were asked to rate their level of decisional conflict using the Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS) [14, 31]. They were first asked to indicate their current preference between five treatment options based on their understanding of those options, and to mark only one option. Their choices were in-center hemodialysis, home hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, conservative management, or unsure. If there was more than one item marked, their answer was coded as “unsure.” The DCS includes 16 items designed to gauge one’s level of uncertainty regarding available treatment options, distress surrounding the decision-making process, information about those treatment options, and their likelihood of implementing a decision based on one’s values. The DCS uses a 5-point scale from 0 (“Strongly Agree”) to 4 (“Strongly Disagree”). To interpret individual results of the scale, raw scores are transformed to a number from 0 to 100 by summing the items together, dividing by 16, then multiplying by 25. Higher scores reflect greater decisional conflict, with scores above 25 relating to “decision-making difficulties” and scores above 37.5 relating to decision delays and/or negative perceptions about the decision [14, 31]. In the current study, the measure has excellent internal consistency (α = .97).

Patient activation

Patient activation was evaluated using a Short Form of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM-SF) [24, 32], which is a 13-item assessment intended to measure patients’ level of skill, knowledge, and confidence regarding how to manage their own health. Participants can choose from five options (“Strongly Disagree,” “Disagree,” “Agree,” Strongly Agree,” and “N/A”). Using an algorithm provided by the authors of the measure, participants’ scores can range from 0 to 100. Participants with low scores tend to experience negative thoughts when having to think about their own health, whereas those with higher scores will be focused on achieving positive health goals without feeling overwhelmed [24, 32]. In the current study, the PAM-SF has excellent internal consistency (α = .92).

Treatment satisfaction

To measure overall CKD-related treatment satisfaction, the authors developed the Kidney Disease Treatment Questionnaire (KDTQ). While there are other treatment satisfaction scales that exist for patients with ESRD, these did not adequately reflect the experiences of patients who have not yet reached ESRD. Existing scales for treatment satisfaction among patients with ESRD tend to focus on their experiences undergoing renal replacement therapy, whereas patients approaching ESRD are not yet undergoing renal replacement therapy. As a group, the authors discussed factors that could specifically influence CKD-related treatment satisfaction for patients approaching ESRD. Based on this discussion, a five-item measure was developed asking patients about their perceived understanding of CKD and CKD-related treatment, their level of involvement in their care, as well as their overall satisfaction with their care. This is the first time the scale has been used. Patients were asked to rate how much they disagreed or agreed with a statement using a 5-point scale from 1 (“Disagree”) to 5 (“Agree”). Scores can range from 5 to 25, and the KDTQ had excellent internal consistency in this sample (α = .88). The survey items can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Kidney Disease Treatment Questionnaire

| 1 = disagree | 2 = somewhat disagree | 3 = neither agree nor disagree | 4 = somewhat agree | 5 = agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In general, I have a good understanding of chronic kidney disease and how it affects me. | |||||

| I have a good understanding of what the treatment options are for kidney failure (e.g., dialysis, transplant). | |||||

| I feel highly involved in making decisions about which kidney disease treatment option is best for me. | |||||

| I am satisfied with the care I receive for my chronic kidney disease. | |||||

| I am satisfied with my involvement in the treatment decision making process for my kidney disease. |

Depressive symptoms

The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) was used to measure current depressive symptoms [33]. It is a nine-item measure in which scores can range from 0 to 27 with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. In the current study, the PHQ-9 has excellent internal consistency (α = .84).

Three other psychosocial measures were included in this survey, but neither were considered nor analyzed in the present study because they were not relevant to the study objectives.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 23. Initial analyses included summarizing demographic and clinical characteristics, and calculating bivariate correlations. Covariate selection was determined using bivariate correlations; variables and/or characteristics that met the selection criteria of p <.05 when compared to decisional conflict were included in subsequent analyses.

Participants’ preferred treatment modalities were also analyzed. First, average scores of decisional conflict, patient activation, and CKD-related treatment satisfaction were obtained for each of the selected treatment modalities. Following these results, the preferred treatment modalities were dummy coded and tested in simple linear regression models as outcomes, and decisional conflict, patient activation, and CKD-related treatment satisfaction as predictors.

A series of linear regressions was performed to identify significant relationships with decisional conflict as the outcome variable, patient activation and CKD-related treatment satisfaction as predictors, and the presence of heart disease as a covariate. A final regression model including CKD-related treatment satisfaction, patient activation, heart disease, and decisional conflict was tested and subsequently entered into PROCESS, an SPSS macro, to test for statistical mediation [34].

Results

Sample Characteristics

A total of 221 patients were identified as eligible based on their medical records. Of these 221 patients, 209 were contacted via mail and 12 were contacted in-person. Of the 209 patients contacted via mail, 6 were deceased and 16 no longer met criteria for the study. Of the remaining 187 patients, 62 could not be reached over the phone, 46 declined participation, 27 expressed interest in participating but never returned their survey, and 55 consented and returned surveys (29%). Of the 12 patients contacted in-person, 1 declined participation, 2 expressed interest in participating but never returned their survey, and 9 consented and returned surveys (75%). The final sample includes 64 participants (n = 32 females, n = 32 males). No cases were excluded from analyses.

Demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 2. The mean participant age was 63.63 years (SD = 15.99). The majority of participants were White (n = 56, 88%). eGFR levels ranged from 7 to 25 mL/min (M = 16.79, SD = 3.88), which is indicative of patients approaching the need for renal replacement therapy. There were 30 participants with diabetes, 52 with high blood pressure, and 19 with heart disease. When asked what dialysis treatment option they preferred, 16 (25%) marked in-center hemodialysis, 7 (11%) home hemodialysis, 10 (16%) peritoneal dialysis, 6 (9%) conservative management, 22 (34%) were unsure, and 3 (5%) participants skipped this question.

Table 2.

Study demographic, clinical, and variable characteristics (N = 64)

| Characteristic | n | % | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | – | – | 63.63 | 15.99 | 20–90 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 32 | 50 | – | – | – |

| Female | 32 | 50 | |||

| >Race/ethnicity | |||||

| White | 58 | 91 | – | – | – |

| Black, African-American | 3 | 5 | |||

| Asian | 1 | 2 | |||

| Pacific Islander or Native Hawaiian | 1 | 2 | |||

| Other | 1 | 2 | |||

| Ethnicity | – | – | – | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 61 | 95 | |||

| Hispanic | 3 | 5 | |||

| Years of education attained | – | – | 14.34 | 3.13 | 10–23 |

| Marital status | – | – | – | ||

| Married | 38 | 59 | |||

| Widowed | 9 | 14 | |||

| Divorced | 7 | 11 | |||

| Separated | 2 | 3 | |||

| Never married | 8 | 13 | |||

| Income | – | – | – | ||

| <$20K | 19 | 30 | |||

| $20–39K | 11 | 17 | |||

| $40–59K | 13 | 20 | |||

| $60–79K | 6 | 9 | |||

| $80–100K | 4 | 6 | |||

| >$100K | 7 | 11 | |||

| Did not report | 4 | 6 | |||

| Self-reported general health rating | – | – | – | ||

| Excellent | 0 | 0 | |||

| Very good | 6 | 10 | |||

| Good | 22 | 36 | |||

| Fair | 28 | 45 | |||

| Poor | 6 | 10 | |||

| Did not report | 2 | 3 | |||

| Other diagnoses | – | – | – | ||

| Diabetes | 30 | 21 | |||

| Heart disease | 19 | 5 | |||

| Hypertension | 52 | 81 | |||

| GFR | – | – | 16.79 | 3.88 | 7–25 |

| Decisional conflict | 31.30 | 20.03 | 0–71.88 | ||

| Patient activation | 65.02 | 16.60 | 38.10–100 | ||

| CKD-related treatment satisfaction | 22.02 | 3.57 | 8–25 | ||

| Depressive symptoms | 5.63 | 5.22 | 0–22 | ||

CKD chronic kidney disease; GFR glomerular filtration rate.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 3 summarizes all bivariate correlations, which identified relationships between decisional conflict, patient activation, and CKD-related treatment satisfaction in the expected directions. Participants in this sample had a high level of decisional conflict, with an average score of 31.30 (SD = 20.03, range 0–71.88). Sixty-five percent of the sample had a decisional conflict score indicating decisional difficulties (>25), and 43% had a score indicating decisional delays (>37.5). Patient activation scores ranged from 38.10 to 100 (M = 65.02, SD = 16.60), and CKD-related treatment satisfaction scores ranged from 8 to 25 (M = 22.02, SD = 3.57). On average, participants reported relatively low levels of depressive symptoms, and the mean score for depressive symptoms was 5.63 (SD = 5.22). Depressive symptoms were not related to any of the key variables. However, the presence of heart disease was related to decisional conflict and patient activation; therefore, it was retained in subsequent regression models as a covariate.

Table 3.

Pearson correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Decisional conflict | − | −.47** | −.32* | .11 | .03 | −.15 | .22 | .11 | −.05 | −.09 | .13 | .05 | .35** | .07 |

| 2. Patient activation | −.47** | − | −.36** | −.13 | −.24 | .15 | −.07 | −.16 | .23 | .24 | −.21 | −.05 | −.28* | −.06 |

| 3. CKD-related treatment satisfaction | −.32* | .36** | − | −.11 | .01 | .10 | .31* | .08 | .19 | .25 | −.02 | −.12 | −.19 | .09 |

| 4. Depressive symptoms | .11 | −.13 | −.11 | − | −.24 | .03 | −.10 | .003 | −.14 | −.38** | .01 | .01 | .05 | −.01 |

| 5. Age | .03 | −.24 | .01 | −.24 | − | −.04 | .24 | .09 | .17 | .18 | .30* | .10 | .34** | .10 |

| 6. Gender | −.15 | .15 | .10 | .03 | −.04 | − | <.001 | −.19 | −.07 | −.17 | −.05 | −.38** | −.02 | −.08 |

| 7. Race | .22 | −.07 | .31* | −.10 | .24 | <.001 | − | .06 | .21 | .19 | −.02 | −.15 | −.02 | .03 |

| 8. Marital status | .11 | −.16 | .08 | .003 | .09 | −.19 | .06 | − | .28* | .41** | −.04 | .12 | .08 | .03 |

| 9. Years of education attained | −.05 | .23 | .19 | −.14 | .17 | −.07 | .21 | .28* | − | .50** | .03 | .15 | .01 | .05 |

| 10. Annual household income | −.09 | .24 | .25 | −.38** | .18 | −.17 | .19 | .41** | .50** | − | −.10 | .15 | −.05 | .12 |

| 11. Diabetes | .13 | −.21 | −.02 | .01 | .30* | −.05 | −.02 | −.04 | .03 | −.10 | − | .19 | .35** | .19 |

| 12. Hypertension | .05 | −.05 | −.12 | .01 | .10 | −.38** | −.15 | .12 | .15 | .15 | .19 | − | .30* | .03 |

| 13. Heart disease | .35** | −.28* | −.19 | .05 | .34** | −.02 | −.02 | .08 | .01 | −.05 | .35** | .30* | − | .15 |

| 14. eGFR | .07 | −.06 | .09 | −.01 | .10 | −.08 | .03 | .03 | .05 | .12 | .19 | .03 | .15 | − |

Gender was coded as 1 = female, −1 = male; race was coded as 1 = White, −1 = non-White; marital status was coded as 1 = married, −1 = not married. CKD chronic kidney disease; eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate.

*p < .05; **p < .01.

Treatment Preference Analyses

Average decisional conflict, patient activation, and CKD-related treatment satisfaction scores were computed for each of the selected treatment modalities (Table 4). After conducting regression analyses, it was found that selecting peritoneal dialysis was significantly associated with lower decisional conflict scores (B = −0.01, SE = 0.002, t(61) = −2.63, p = .01), and higher patient activation scores (B = 0.01, SE = 0.003, t(62) = 2.17, p = .03). In addition, selecting “Unsure” was significantly associated with higher decisional conflict scores (B = 0.01, SE = 0.003, t(61) = −0.34, p < .01).

Table 4.

Preferred treatment modalities by average decisional conflict, patient activation, and CKD-related treatment satisfaction scores

| In-center hemodialysis | Home hemodialysis | Peritoneal dialysis | Conservative management | Unsure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 16 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 22 |

| Decisional conflict | 24.4 | 35.0 | 16.7 | 26.8 | 45.1 |

| Patient activation | 66.9 | 65.1 | 75.2 | 55.8 | 61.5 |

| CKD-related treatment satisfaction | 21.1 | 23.7 | 23.3 | 22.7 | 21.1 |

CKD chronic kidney disease.

Primary Analyses

To examine the hypothesis that higher CKD-related treatment satisfaction and higher patient activation were related to lower decisional conflict, a series of linear regressions was performed with decisional conflict as the outcome variable. In Model 1, treatment satisfaction was found to be significantly associated with decisional conflict (B = −1.51, SE = 0.69, t(56) = −2.19, p = .03). Model 2 revealed that patient activation was also associated with decisional conflict (B = −0.49, SE = 0.14, t(57) = −3.48, p = .001). In other words, higher CKD-related treatment satisfaction and higher patient activation corresponded with lower self-reported decisional conflict, thus confirming our hypothesis. In Model 3, a multiple regression was conducted with CKD-related treatment satisfaction and patient activation as predictors, and decisional conflict as the outcome variable. First, tests for multicollinearity indicated low levels of multicollinearity between CKD-related treatment satisfaction and patient activation (variance inflation factor = 1.15). More importantly, it was revealed that patient activation still significantly predicted decisional conflict while controlling for CKD-related treatment satisfaction (B = −0.46, SE = 0.15, t(55) = −3.04, p = .004). However, CKD-related treatment satisfaction no longer significantly predicted decisional conflict when controlling for patient activation (B = −0.83, SE = 0.68, t(55) = −1.21, p = .23). In Models 1, 2, and 3, heart disease was included as a covariate. The pattern of significance in no way shifts with the inclusion of heart disease in the models. This information can be found in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of regressions with decisional conflict as the outcome variable while controlling for heart disease

| R 2 | Unstandardized coefficients (SE) | t-test | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | .19 | ||

| CKD-related treatment satisfaction | 1.51 (0.69) | t(56) = −2.19* | |

| Heart disease | 12.80 (5.31) | t(56) = 2.41* | |

| Model 2 | .28 | ||

| Patient activation | −0.49 (0.14) | t(57) = −3.48** | |

| Heart disease | 10.31 (5.09) | t(57) = 2.02* | |

| Model 3 | .31 | ||

| Patient activation | −0.46 (0.15) | t(55) = −3.04** | |

| CKD-related treatment satisfaction | −0.83 (0.68) | t(55) = −1.21 | |

| Heart disease | 9.00 (5.11) | t(55) = 1.70 |

CKD chronic kidney disease.

*p ≤ .05; **p ≤ .01.

Statistical Mediation Analysis

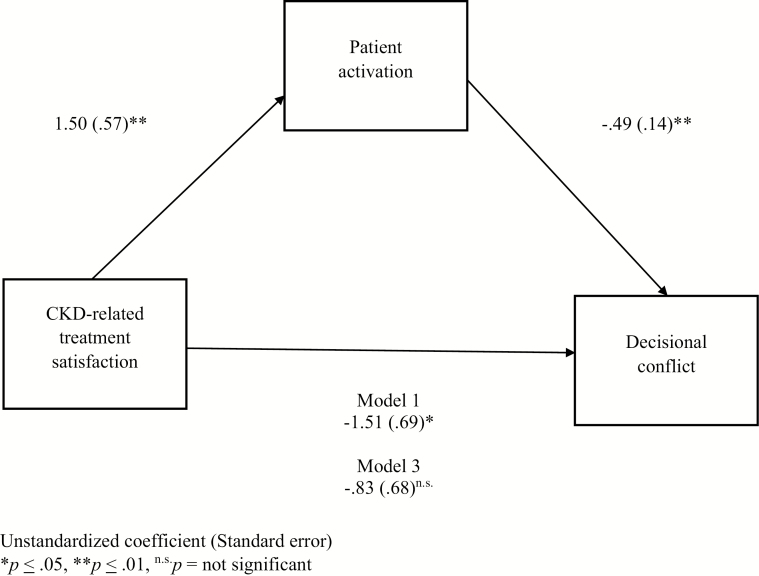

Because patient activation remained statistically significant in Model 3 when predicting decisional conflict, we decided to test whether patient activation played a statistical mediational role between CKD-related treatment satisfaction and decisional conflict. The first step to confirm patient activation as a statistical mediator involved conducting an additional linear regression, with CKD-related treatment satisfaction as the predictor for patient activation [29]. These analyses confirmed a significant statistical relationship (B = 1.50, SE = 0.57, t(56) = 2.61, p = .01). The model was subsequently entered into PROCESS, with CKD-related treatment satisfaction as the predictor, patient activation as the mediator, decisional conflict as the outcome variable, and heart disease as a covariate [34]. PROCESS uses a bootstrapping procedure to confirm a significant indirect effect [34]. The bootstrapping procedure based on 5,000 samples estimated the SE and confirmed a statistically significant indirect effect (B = −1.51, SE = 0.69, bias corrected 95% CI −2.89 to −0.13). The total model accounted for a significant portion of the variance in decisional conflict, R2 = .18, F(2, 56) = 6.50, p = .003, confirming the statistical mediational role of patient activation. Figure 1 shows the results for the final mediation model.

Fig. 1.

Mediation model when controlling for heart disease.

Discussion

The present study examined relationships between CKD-related treatment satisfaction, decisional conflict, and patient activation in patients approaching ESRD. Specifically, the study found patient activation statistically mediated the association between CKD-related treatment satisfaction and decisional conflict when controlling for comorbid heart disease. Results showed that higher CKD-related treatment satisfaction predicted lower decisional conflict through higher patient activation. These results are consistent with a prior study that demonstrated patients with cancer who were highly activated were 10 times more likely to believe their treatment plan reflected their own values, a factor associated with lower decisional conflict [25]. In the current study, other demographic and clinical variables, such as age, gender, race, marital status, education, income, diabetes, hypertension, eGFR, and depressive symptoms, were not associated with decisional conflict.

Results of the present study have implications for future research and clinical practice. First, the treatment decision-making experience of patients who are approaching ESRD has received little attention, and the current study provides insight into patients’ experiences during this difficult process. The majority of the current sample had a high level of decisional conflict. This fits with past observations and reports that patients approaching ESRD typically have trouble deciding which treatment modality to pursue because patients are relatively uninformed about the options and their associated risks and benefits [19, 35]. Additionally, when there is an urgent need for renal replacement therapy due to rapid progression of kidney disease, patients are tasked with selecting a treatment without fully considering how appropriate each treatment option is for them [1, 19]. Furthermore, the ESRD treatment options substantially change one’s day-to-day life compared to many other health-related decisions. Finally, patients who have found a treatment option that is right for them after they have begun another renal replacement therapy often feel it is too late to switch treatment modalities [11–13]. Given these unique challenges associated with the ESRD treatment context, an understanding of ways the patient decision-making process might be facilitated is particularly critical and will inform shared decision-making interventions for this population.

The present findings suggest a need for interventions to improve the decision-making process among patients approaching ESRD, and that encouraging patients’ greater involvement in their care might be a viable route for achieving better decisional outcomes. First, patients should be aware of and informed about what treatment options are available to them. In a previous study, an educational intervention aimed at increasing patient knowledge about home-based dialysis methods resulted in greater selection of those treatment modalities [36], which, although infrequently selected among ESRD patients in the USA, are associated with reduced long-term healthcare costs, greater autonomy, and improved health-related quality of life [3]. Second, interventions with a shared decision-making approach may facilitate decision-making satisfaction. A shared decision-making approach involves healthcare providers informing and advising patients on their treatment options and ultimately, having the patient and healthcare provider collaborate to make a final decision [19, 37–39]. One way to initiate shared decision-making and potentially reduce decisional stress is by using a decision aid [40]. Decision aids can inform patients about their treatment options, provide information on the benefits and risks of those options, report on probabilities of treatment outcomes based on certain patient profiles, and help patients clarify their values [40–44]. Decision aids can be offered through different media channels such as pamphlets, videos, and online resources [40]. Providing patients with a decision aid during a clinical encounter gives them the opportunity to voice their concerns and preferences, and it could also serve as an approach to facilitate patient activation. A decision aid also gives healthcare providers the opportunity to provide decisional support to their patients.

An additional exploratory finding of the present study found that participants who selected peritoneal dialysis as their treatment preference had significantly lower decisional conflict scores and significantly higher patient activation scores compared to participants who chose any other treatment modality. Since patients undergoing peritoneal dialysis must consistently exhibit good self-management skills for their dialysis routine, it is reasonable to expect they would also exhibit good self-management skills in other health-related situations; in other words, they are highly activated patients. Furthermore, evidence suggests that patients who are undergoing peritoneal dialysis received more pre-dialysis education before reaching ESRD [13, 36], which may explain why participants who selected peritoneal dialysis as their treatment preference had lower decisional conflict scores. Unsurprisingly, selecting “Unsure” for treatment preferences was significantly associated with higher decisional conflict scores.

Limitations

Although the present study provides insights into potential mechanisms to support decision-making in patients approaching ESRD, there are several limitations. The cross-sectional nature of this study cannot confirm causal inferences about the relationships between the variables of interest. The mediation analysis was data-driven, so it is possible, for example, that in a larger sample of patients approaching ESRD, patient activation changes occur first and are subsequently mediated by changes in treatment satisfaction, and future longitudinal work could illuminate the causal relationship or temporal ordering. On the other hand, in a theoretical model, it is feasible to view patient activation as a mediator since it can increase in individuals through clinical interventions [21–23].

This is the first time the KDTQ has been used, and the items were not pilot tested beforehand. While this clearly limits what we know about the validity and reliability of the measure, it did have excellent internal consistency in the present sample (α = .88). Furthermore, the authors consulted other nephrologists during development and final approval of the scale. Future research should conduct validity studies and additional reliability statistics in a much larger sample of patients approaching ESRD so the scale can continue to be used to measure CKD-related treatment satisfaction in this understudied population.

The sample size of the present study was relatively small and the response rate for the survey was extremely low (32%) despite efforts to contact eligible patients encouraging them to participate. The patient activation scores of the present study are considered high (M = 65.02), which may explain why the present sample was particularly motivated to participate in our study. Therefore, the sample is not representative of the full spectrum of patient activation in this population. An additional limitation is that the sample was relatively homogenous in terms of racial and ethnic characteristics, with the majority of the sample (88%) identifying as White and non-Hispanic. Rates of ESRD are higher for Blacks and Hispanics than for Whites [1], therefore the present findings do not generalize to the greater patient population. Future research on patients approaching ESRD should be conducted in more diverse samples to determine whether these results change across racial and ethnic groups.

Despite all these limitations, the within-sample findings from the statistical mediation are still of value and warrant further research to increase knowledge about this specific patient population and to create interventions to improve their treatment decision-making processes.

Conclusions

The present study identified a high level of treatment-related decisional conflict among patients approaching ESRD. Moreover, patient activation and CKD-related treatment satisfaction were both identified as significant correlates of decisional conflict, with patient activation acting as a statistical mediator of the association between treatment satisfaction and decisional conflict. Based on our findings, future research should examine ways to improve the decision-making process for advanced CKD patients. This could be done by using tailored decision aids or other strategies to better engage patients in the decision-making process as they consider which ESRD-related treatment modality is right for them.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards Miriam Vélez-Bermúdez, Alan J. Christensen, Ellen M. Kinner, Anne I. Roche, and Mony Fraer declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

References

- 1. United States Renal Data System. End-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the United States. Vol.2 2017. Available at https://www.usrds.org/2017/download/2017_Volume_2_ ESRD_n_the_US.pdfAccessibility verified March 29, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Himmelfarb J, Ikizler TA. Hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(19):1833–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harwood L, Leitch R. Home dialysis therapies. Nephrol Nurs J. 2006;33(1):46. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ellam T, Wilkie M. Peritoneal dialysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;43(8):484– 488. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koo DD, Welsh KI, McLaren AJ, Roake JA, Morris PJ, Fuggle SV. Cadaver versus living donor kidneys: impact of donor factors on antigen induction before transplantation. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1551–1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. O’Connor NR, Kumar P. Conservative management of end-stage renal disease without dialysis: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(2):228–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Avşar U, Avşar UZ, Cansever Z, et al. Caregiver burden, anxiety, depression, and sleep quality differences in caregivers of hemodialysis patients compared with renal transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2015;47(5):1388–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Morton RL, Snelling P, Webster AC, et al. Dialysis modality preference of patients with CKD and family caregivers: a discrete-choice study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wong CF, McCarthy M, Howse ML, Williams PS. Factors affecting survival in advanced chronic kidney disease patients who choose not to receive dialysis. Ren Fail. 2007;29(6):653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE. Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1955–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Murray MA, Brunier G, Chung JO, et al. A systematic review of factors influencing decision-making in adults living with chronic kidney disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(2):149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Br Med J. 2010;340(7742):c112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harwood L, Clark AM. Understanding pre-dialysis modality decision-making: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(1):109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O’Connor AM. Validation of a Decisional Conflict Scale. Med Decis Mak. 1995;15(1):25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Des Cormiers A, Légaré F, Simard S, Boulet LP. Decisional conflict in asthma patients: a cross sectional study. J Asthma. 2015;52(10):1084–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Noble H, Brazil K, Burns A, et al. Clinician views of patient decisional conflict when deciding between dialysis and conservative management: qualitative findings from the PAlliative Care in chronic Kidney diSease (PACKS) study. Palliat Med. 2017;31(10):921–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thompson-Leduc P, Turcotte S, Labrecque M, Légaré F. Prevalence of clinically significant decisional conflict: an analysis of five studies on decision-making in primary care. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stephens RL, Xu Y, Volk RJ, et al. Influence of a patient decision aid on decisional conflict related to PSA testing: a structural equation model. Health Psychol. 2008;27(6):711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen N, Lin Y, Liang S, Tung H, Tsay S, Wang T. Conflict when making decisions about dialysis modality. J Clin Nurs. 2017;27(1–2):e138–e146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Castillo A, Giachello A, Bates R, et al. Community-based diabetes education for Latinos: the diabetes empowerment education program. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(4):586–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shively MJ, Gardetto NJ, Kodiath MF, et al. Effect of patient activation on self-management in patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;28(1):20–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Terry PE, Fowles JB, Xi M, Harvey L. The ACTIVATE study: results from a group-randomized controlled trial comparing a traditional worksite health promotion program with an activated consumer program. Am J Health Promot. 2011;26(2):e64–e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a Short Form of the Patient Activation Measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6p1):1918–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hibbard JH, Mahoney E, Sonet E. Does patient activation level affect the cancer patient journey? Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(7):1276–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bennett JK, Fuertes JN, Keitel M, Phillips R. The role of patient attachment and working alliance on patient adherence, satisfaction, and health-related quality of life in lupus treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Viller F, Guillemin F, Briançon S, Moum T, Suurmeijer T, van den Heuvel W. Compliance to drug treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a 3 year longitudinal study. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2114–2122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barbosa CD, Balp MM, Kulich K, Germain N, Rofail D. A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wright Nunes JA, Wallston KA, Eden SK, Shintani AK, Ikizler TA, Cavanaugh KL. Associations among perceived and objective disease knowledge and satisfaction with physician communication in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2011;80(12):1344–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. United States Renal Data System. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the United States Vol. 1 2017. Available at https://www.usrds.org/2017/download/2017_Volume_1_CKD_in_the_US.pdfAccessibility verified February 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31. O’Connor AM. User Manual-Decisional Conflict Scale. Ottumwa Hosp Res Ins. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4p1):1005–1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35. McPherson L, Basu M, Gander J, et al. Decisional conflict between treatment options among end‐stage renal disease patients evaluated for kidney transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2017;31(7):e12991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Manns BJ, Taub K, Vanderstraeten C, et al. The impact of education on chronic kidney disease patients’ plans to initiate dialysis with self-care dialysis: a randomized trial. Kidney Int. 2005;68(4):1777–1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Joosten EA, DeFuentes-Merillas L, de Weert GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CP, de Jong CA. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77(4):219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Baars JE, Markus T, Kuipers EJ, van der Woude CJ. Patients’ preferences regarding shared decision-making in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: results from a patient-empowerment study. Digestion. 2010;81(2):113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hölzel LP, Kriston L, Härter M. Patient preference for involvement, experienced involvement, decisional conflict, and satisfaction with physician: a structural equation model test. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. O’Connor AM, Rostom A, Fiset V, et al. Decision aids for patients facing health treatment or screening decisions: systematic review. Br Med J. 1999;319(7212):731–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cuypers M, Lamers RE, Kil PJ, van de Poll-Franse LV, de Vries M. Impact of a web-based treatment decision aid for early-stage prostate cancer on shared decision-making and health outcomes: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16(1):231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sherman KA, Shaw LK, Winch CJ, et al. ; BRECONDA Collaborative Research Group Reducing decisional conflict and enhancing satisfaction with information among women considering breast reconstruction following mastectomy: results from the BRECONDA randomized controlled trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:592e–602e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fagerlin A, Pignone M, Abhyankar P, et al. Clarifying values: an updated review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13(Suppl. 2):S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. O’Connor AM, Tugwell P, Wells GA, et al. A decision aid for women considering hormone therapy after menopause: Decision support framework and evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;33(3):267–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]