Abstract

Background

Gut microbiota has been increasingly acknowledged to shape significantly human health, contributing to various autoimmune diseases, both intestinal and non-intestinal, including multiple sclerosis (MS). Gut microbiota studies in patients with relapsing remitting MS strongly suggested its possible role in immunoregulation; however, the profile and potential of gut microbiota involvement in patients with primary progressive MS (PPMS) patients has received much less attention due to the rarity of this disease form. We compared the composition and structure of faecal bacterial assemblage using Illumina MiSeq sequencing of V3-V4 hypervariable region of 16S rRNA genes amplicons in patients with primary progressive MS and in the healthy controls.

Results

Over all samples 12 bacterial phyla were identified, containing 21 classes, 25 orders, 54 families, 174 genera and 1256 operational taxonomic units (OTUs). The Firmicutes phylum was found to be ultimately dominating both in OTUs richness (68% of the total bacterial OTU number) and in abundance (71% of the total number of sequence reads), followed by Bacteroidetes (12 and 16%, resp.) and Actinobacteria (7 and 6%, resp.). Summarily in all samples the number of dominant OTUs, i.e. OTUs with ≥1% relative abundance, was 13, representing much less taxonomic richness (three phyla, three classes, four orders, six families and twelve genera) as compared to the total list of identified OTUs and accounting for 30% of the sequence reads number in the healthy cohort and for 23% in the PPMS cohort. Human faecal bacterial diversity profiles were found to differ between PPMS and healthy cohorts at different taxonomic levels in minor or rare taxa. Marked PPMS-associated increase was found in the relative abundance of two dominant OTUs (Gemmiger sp. and an unclassified Ruminococcaceae). The MS-related differences were also found at the level of minor and rare OTUs (101 OTUs). These changes in OTUs’ abundance translated into increased bacterial assemblage diversity in patients.

Conclusion

The findings are important for constructing a more detailed global picture of the primary progressive MS-associated gut microbiota, contributing to better understanding of the disease pathogenesis.

Keywords: Multiple sclerosis, Primary progressive course, Humans, Faecal bacterial assemblage, 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing

Background

Identification of specific microorganisms that live in the gut, which was made possible by methodological and instruments’ advances, has contributed to revealing the complex relationship between the microbiota and the host.

Gut microbiota has been increasingly and explicitly acknowledged to shape significantly human health, in particular contributing to various autoimmune diseases, both intestinal and non-intestinal, such as multiple sclerosis, type-1 diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus, psoriasis, schizophrenia, and some other disorders [1, 2].

Multiple sclerosis (MS), affecting the central nervous system, has an unclear etiology involving both genetic and extrinsic factors. Recent evidence indicates that autoimmune activation may happen in the intestine, following an interaction of bacterial components of the gut flora with local CNS autoreactive T cells [3]. Although by now it is commonly acknowledged that MS patients have dysbiosis compared to healthy individuals [4, 5], the cause-effect relationship between MS and gut microbiota dysbiosis has not been so far unequivocally established [2, 6]. However, some recently reported results are quite suggestive: for instance, transplantation of gut microbiota from multiple sclerosis patients was found to enable spontaneous autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice [7], and new hypotheses, based on microbes’ involvement, have been proposed as causes for a range of chronic inflammatory diseases, including MS [8]. Accordingly, it has been hypothesized that intervention of the gut microbiome could result in safer novel therapeutic strategies to treat the disease [4, 9]. Yet the development of such strategies needs a more detailed picture of microbiome specifics in the MS-afflicted cohorts in different regions of the world and an improved understanding of the interactions between the microbiota and the host [10].

Pathological and clinical symptoms of MS vary widely [11], the heterogeneity often confusing for diagnostics [12, 13]. Generally several subtypes of the disease are distinguished, among them relapsing-remitting and primary progressive being the most common and the most rare ones, respectively [14]. The former is subdivided into several forms, most commonly with and without relapses, and the latter also is commonly subdivided into the primary and secondary course. There is lack of understanding of pathogenic mechanisms driving progressive MS [15]. In primary progressive MS (PPMS) neurodegenerative mechanisms are believed to dominate, while in the more frequent relapsing forms the autoimmune inflammation is believed to be the major driver, most likely due to different genetic background [16]. Gut microbiota in MS patients has been studied mainly in patients with relapsing remitting MS, and its possible role in immunoregulation was suggested, while the profile and potential in PPMS patients has not been studied yet.

The aim of this study was to investigate gut 16S microbiome of patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) in comparison with the healthy subjects and to reveal the MS-related shifts.

Results

After quality filtering and chimera removal a total of 1256 different OTUs were identified at 97% sequence identity level, of which the overwhelming majority (1252) was Bacteria, the rest four representing the Euryarchaeota phylum of the Archaea domain.

Over all samples 12 bacterial phyla were identified, containing 21 classes, 25 orders, 54 families and 174 genera, alongside with unidentified taxa. Most of the bacterial OTUs represented the Firmcutes phylum (857 OTUs, or ca. 68% of the total bacterial OTU number), with Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria being the second and the third most OTU-rich phyla with 148 (12%) and 84 OTUs (7%), respectively.

Thus the overwhelming majority of OTUs in the faecal bacterial assemblages were ascribed to the Firmicutes phylum.

Clostridia was the OTU-richest class (669 OTUs), accounting for 53% of the total OTU richness, with Bacteroidia (135 OTUs) and Actinobacteria (79) contributing 11 and 6%, respectively. Thus these three classes drastically prevailed in faecal bacterial assemblages.

Summarily in all samples the number of dominant OTUs, i.e. OTUs contributing ≥1% into the total sequence number in a sample, was 13, i.e. 1.0% of the total number of OTUs. They represented 3 phyla, 3 classes, 4 orders, 6 families and 12 genera, i.e. much less taxonomic richness as compared to the total list of identified OTUs. The dominant OTUs accounted for 30% of the sequence reads in the healthy cohort and for 23% number in the PPMS cohort.

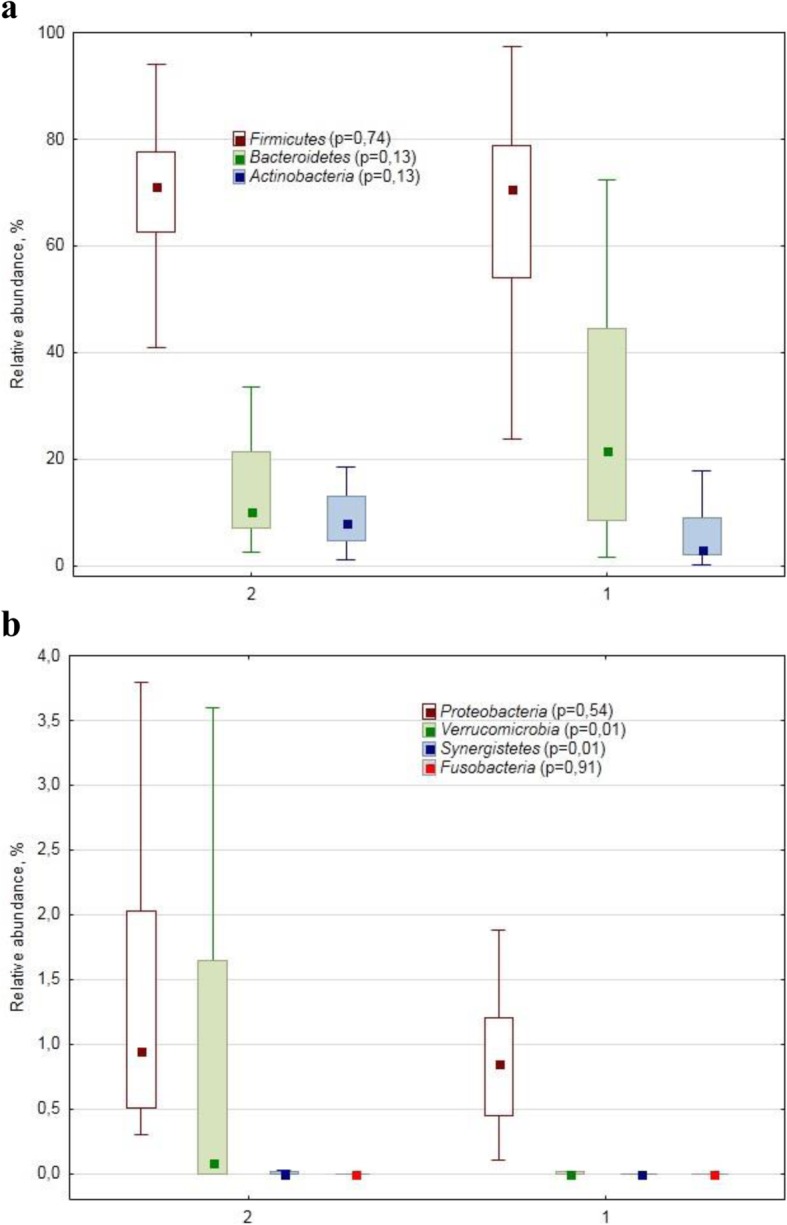

The dominant phyla structure was quite similar in these cohorts (Fig. 1a). However, at the minor/rare phylum level, i.e. phyla with the number of sequence reads contributing less than 1% into the total number of sequence reads, there was a difference in bacterial assemblage structure as Verrucomicrobiae sequences were more abundant in PPMS (0.09%) as compared with the healthy (0.00%) cohort (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Relative abundance (%) of dominant (a) and minor/rare (b) phylum-specific 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequences in human faecal samples collected from patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (2) and from healthy subjects (1). The marker shows a median; the box shows the 75–25% quartile range, while the lines indicate the fluctuation range. The p-values of the Mann-Whitney test for the cohorts’ comparison are shown in brackets after the phylum name

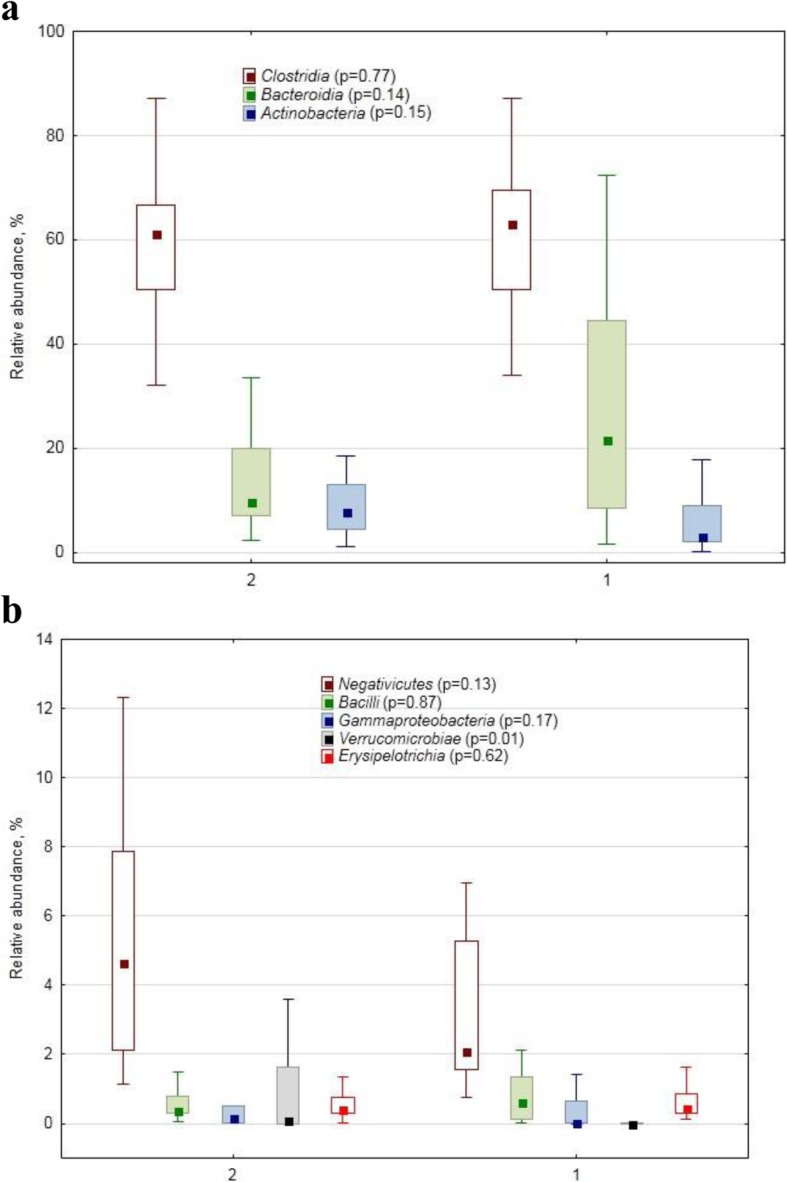

At the class level the relative abundance of Clostridia representatives was lower in the PPMS assemblages (61.2 vs. 63.2%, resp., Fig. 2a). There was also a difference (p = 0.0008) between the healthy (0.06%) and PPMS (0.40%) cohorts in the relative abundance of Deltaproteobacteria class-specific reads, as well as in Verrucomicrobiae (0.00 vs. 0.09%, resp., p = 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Relative abundance (%) of dominant (a) and minor/rare (b) class–specific 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequences in human faecal samples collected from healthy subjects (1) and from patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (2). The marker shows a median; the box shows the 75–25% quartile range, while the lines indicate the fluctuation range The p-values of the Mann-Whitney test for the conhorts’ comparison are shown in brackets after the class name

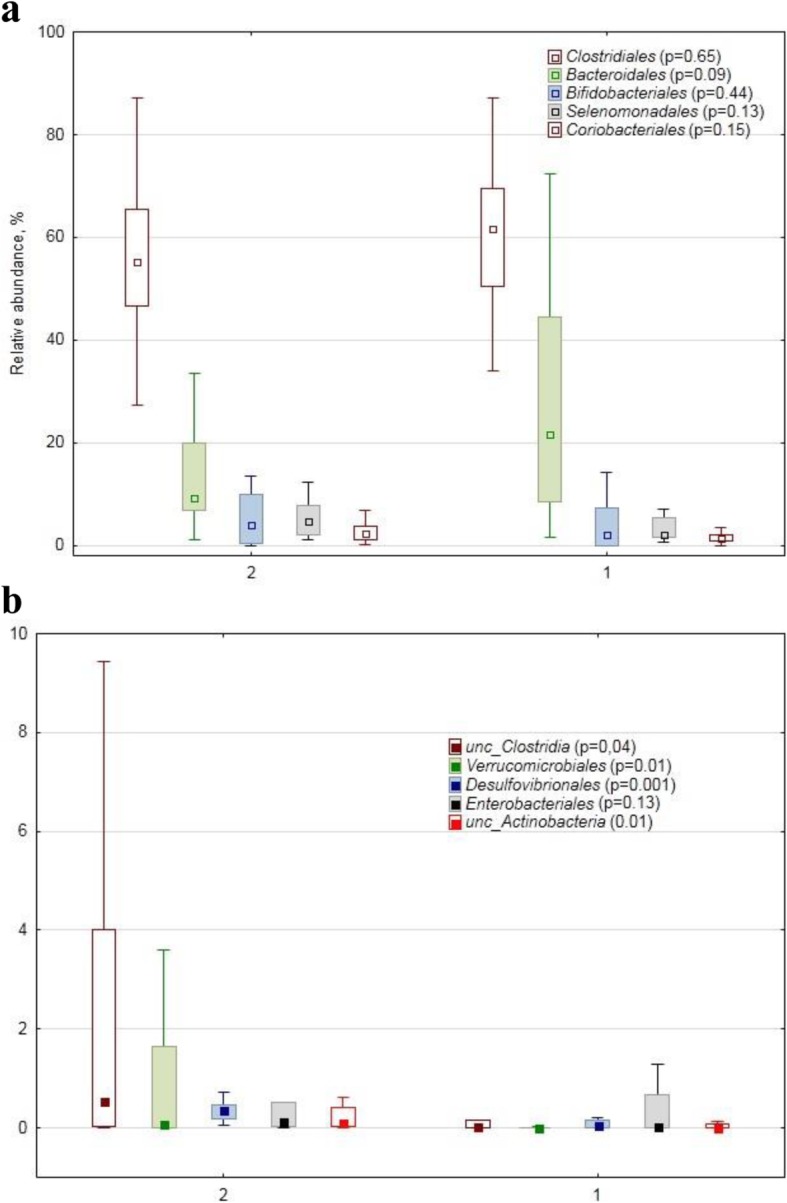

At the order level no differences were detected among the dominant ones (Fig. 3a), while statistically significant differences between the healthy and PPMS cohorts were found in some minor and rare orders (Fig. 3b): Actinomycetales (0.01 vs. 0.03%), Verrucomicrobiales (0.00 vs. 0.09, p = 0.01), Desulfovibrionales (0.06 vs. 0.36%, p = 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Relative abundance (%) of dominant (a) and minor/rare (b) order–specific 16S rDNA sequences in human faecal samples collected from the healthy subjects (1) and from the patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (2). The marker shows a median; the box shows the 75%25% quartile range, while the lines indicate the fluctuation range The p-values of the MannWhitney test for the cohorts’ comparison are shown in brackets after the order name

At the family level the assemblage structure (Table 1) displayed some differences between healthy and PPMS patients, related mostly to minor or rare families (8 families were explicitly classified, and two were unclassified).

Table 1.

Relative abundance (%, median values) of family-specific 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequences in human faecal samples collected from healthy subjects and patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS)

| Family | PPMS | Healthy | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ruminococcaceae | 31.9 | 28.2 | 0.23 |

| Lachnospiraceae | 17.1 | 26.5 | 0.06 |

| Bacteroidaceae | 2.7 | 1.6 | 0.84 |

| Prevotellaceae | 1.8 | 1.0 | 0.74 |

| Bifidobacteriaceae | 4.0 | 2.1 | 0.44 |

| unc. Clostridiales a | 4.2 | 2.6 | 0.09 |

| Coriobacteriaceae | 2.2 | 1.4 | 0.15 |

| unc. Firmicutes | 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.01b |

| Veillonellaceae | 2.2 | 1.9 | 0.87 |

| Acidaminococcaceae | 1.1 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Porphyromonadaceae | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.23 |

| unc. Clostridia | 0.5 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| Eubacteriaceae | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.01 |

| Rikenellaceae | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.07 |

| Streptococcaceae | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.59 |

| Erysipelotrichaceae | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.62 |

| Verrucomicrobiaceae | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| unc. Bacteria | 0.31 | 0.06 | 0.16 |

| Peptostreptococcaceae | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.12 |

| Lactobacillaceae | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.10 |

| Methanobacteriaceae | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Clostridiaceae_1 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.57 |

| Sutterellaceae | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.93 |

| Desulfovibrionaceae | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.00 |

| Enterobacteriaceae | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.13 |

| Actinomycetaceae | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Clostridiales_i.s._XIII | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.17 |

| Oxalobacteraceae | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.03 |

| Christensenellaceae | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.01 |

| Corynebacteriaceae | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.01 |

a “unc.” stands for unclassified;

b the rows with statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) differences between the cohorts’ medians are highlighted in bold

The Acidaminococcaceae family in our study was represented by 3 genera (Phascolarctobacterium, Acidaminococcus and some unidentified one) and 8 OTUs, namely Phascolarctobacterium faecium, Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens, Acidaminococcus intestini, Acidaminococcus fermentans, as well as 3 unidentified ones. Eubacteriaceae family was represented by 2 genera (Eubacterium, Anaerofustis) and 9 OTUs; Verrucomicrobiaceae had one genus (Akkermansia) and one OTU, Desulfovibrionaceae was represented by two genera, i.e. Desulfovibrio with 7 OTUs, and Bilophila with one. Actinomycetaceae had 4 genera, with Actinomyces contributing 9 OTUs and Mobiluncus, Varibaculum and Trueperella each contributing just one. Corynebacteriaceae had 4 OTUs of the Corynebacterium genus. Only one OTU represented Oxalobacteraceae, and two OTUs represented Christensenellaceae family.

As for the dominant OTUs, we found some marked PPMS-associated increase in the relative abundance of Gemmiger sp. and an unclassified Ruminococcaceae (Table 2). In contrast to the dominant OTUs, a larger number of minor and rare OTUs were found to show PPMS-related differences: 101 OTUs at the significance level of 0.05 and 85 OTUs at the significance level of 0.10. (Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2).

Table 2.

Relative abundance (%, median values) of dominant OTUs in human faecal samples collected from the healthy subjects and patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS)

| Dominant OTUs | PPMS | Healthy subjects | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | 11.2 | 11.3 | 0.35 |

| 2 | Bifidobacterium sp. | 1.8 | 0.1 | 0.12 |

| 3 | unc. Lachnospiraceae a | 2.5 | 4.2 | 0.19 |

| 4 | Ruminococcus bromii | 3.5 | 2.3 | 0.22 |

| 5 | Gemmiger sp. | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.03b |

| 6 | Collinsella sp. | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.47 |

| 7 | Bacteroides sp. | 1.4 | 0.7 | 0.71 |

| 8 | Blautia wexlerae | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.10 |

| 9 | Prevotella copri | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.46 |

| 10 | Eubacterium hallii | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.14 |

| 11 | unc.Ruminococcaceae | 1.7 | 0.2 | 0.00 |

| 13 | Anaerostipes sp. | 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.22 |

| 16 | Blautia luti | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.08 |

a “unc.” stands for unclassified;

b the rows with statistically significant (P ≤ 0.05) differences between the cohorts’ medians are highlighted in bold

Statistically significant differences between the studied healthy and PPMS cohorts were detected in such indices as OTU richness, Berger-Parker, Flyvbjerg and Mirror (Table 3), all indicating higher diversity in PPMS-associated bacterial assemblage.

Table 3.

Alpha-biodiversity indices of bacterial assemblages in human faecal samples collected from the healthy subjects and patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS)

| Index | PPMS | Healthy | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richnessa | 163 | 129 | 0.03 |

| Chao1 | 231 | 177 | 0.10 |

| Berger-Parker | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.03 |

| Simpson | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.11 |

| Dominance | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| Buzas-Gibson | 0.020 | 0.015 | 0.12 |

| Equitability | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.22 |

| Jost | 28 | 22 | 0.11 |

| Shannon | 3.8 | 3.6 | 0.14 |

| Robbins | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.12 |

| Flyvbjerg | 165 | 117 | 0.05 |

| Mirror | 272 | 219 | 0.04 |

a Rows with significant (P ≤ 0.05) differences between the values are highlighted in bold

Discussion

We could not compare our results with other PPMS cohorts, as, similar to other researchers [17], we failed to find the data on PPMS-associated gut microbiome obtained using metagenomic methodology. It might seem surprising, as bibliography search commonly produces review articles stating that patients with MS have altered microbiome as compared to healthy people. However, most of such statements pertain to the patients with relapse-remitting subtype of MS as it is the most common subtype of the disease, while PPMS one is rather rare [14] and, consequently, the information on gut bacterial assemblage structure and composition is also scarce.

We found altered gut bacterial assemblage in the PPMS patients as compared with the healthy subjects. At the phylum level no difference in faecal bacterial assemblage structure between the healthy and PPMS cohorts was found in the dominant phyla abundance. However, some PPMS-associated differences were detected in the relative abundance of the rare phyla, i.e. phyla represented by just few OTUs and contributing much less than 1% into the total number of sequences: for example, Verrucomicrobiae with just 4 OTUs showed PPMS-related increase due to Akkermansia muciniphila. This result agrees with the earlier finding that increased A. muciniphila relative abundance was associated with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (an animal model of MS) [18, 19]. Akkermansia muciniphila is a mucin-degrading bacterium, in such capacity not being beneficial for human health; however, it is also a propionogenic bacterium, believed to have several health benefits in humans [20].

Synergistetes phylum, with its practically negligible relative abundance and represented by just 6 OTUs, also had increased PPMS-associated relative abundance. The phylum was found to be positively correlated with normal immune homeostasis [21]; however, earlier research found the phylum association with chronic osteomyelitis of the jaw [22]. Albeit the interpretation of the phylum significance, if any, in MS-associated microbiome is difficult, such rare phyla might be important in ecological, physiological and/or pathogenic interplay within the human gut microbiome and between the latter and the host organism.

Firmicutes phylum predominated in all samples; and most pronounced MS-related alterations were found also in the relative abundance of some phylum representatives, such as Acidaminococcaceae, Eubacteriaceae, Christensenellaceae, as well as some unclassified Firmicutes and Clostridia. The Acidaminococcus and Phascolarctobacterium genera, representing Acidaminococcaceae, are known as common commensals in the human gut [23, 24], beneficial for health. Both Eubacteriaceae genera, detected in our study, namely Eubacterium and Anaerofustis with 6 and 3 OTUs, respectively, are beneficial gut bacteria [25–27]. Quite a lot of OTUs with differential relative abundance in PPMS and healthy cohorts also belonged to Firmicutes phylum.

The increased relative abundance of sequences, representing beneficial bacteria, in PPMS-associated assemblage confuses the pathophysiological interpretation of their association with MS, the situation complies with earlier conclusion that so far little consistency in the MS-associated bacterial taxa has been found [28].

Desulfovibrionales order, represented by Desulfovibrionaceae family with Bilophila and Desulfovibtio genera, in their turn represented respectively by one OTU (Bilophila wadsworthia) and 7 OTUs of unclassified Desulfovibrio, were found to be more abundant in the PPMS cohort. Bilophila is a known pathobiont [29, 30]. Although Desulfovibrio piger is found in some healthy human guts, a greater abundance of this species may be associated with certain gastrointestinal diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease [31] or autism [32].

Biodiversity indices serve to compact information about communities, assemblages, guilds etc. of living organisms; thus the indices are useful for comparing large arrays of metagenomic data. We found that four α-biodiversity indices were higher in the primary progressive MS cohort, indicating the presence of a bigger set of players, albeit minor and rare ones, in the PPMS-associated gut microbiota as compared with the healthy one. However, earlier a trend towards lower species richness was found in relapsing-remitting MS patients with active disease as compared with the healthy controls [33], using the same methodology, i.e.V3-V4 rRNA gene region for PCR amplification and sequencing by Illumina MiSeq, as in our study.

The aberrant MS-related gut microbiota, found in our study, supports the idea of using diet and/or other means to modulate gut microbiota in an attempt to alleviate [9] and possibly prevent MS [34] even without certainty about cause-effect relationship between microbiome members and MS progress. However, the rarity of most of the PPMS-associated gut bacteria makes further investigation of their physiological and pathogenic relevance quite challenging.

All the PPMS patients included in our study received neither oral nor injective disease modifying therapies (DMTs), which could have modified the gut microbiome, as was shown earlier for patients with the relapsing forms of MS [35]. Quite recently gut microbiota-dependent T cells were found altered in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis [36], suggesting similar possibility in the PPMS as well.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study presents the first inventory of the faecal bacterial assemblage composition and structure in patients affected by primary progressive multiple sclerosis. We provide evidence that human faecal bacterial diversity profiles revealed differences between PPMS and healthy cohorts at different taxonomic levels. A number of MS-associated changes, detected in some rare bacterial OTUs’ abundance, translated into increased diversity in MS patients. The findings are important to get a more detailed global picture of the MS-associated bacterial assemblage, contributing to better understanding of the disease pathogenesis (associated both with immunoregulation and neurodegeneration) and suggesting, at least for the alleviation therapy, possible avenues.

Methods

Participants and faecal sample collection

Healthy subjects (n = 15) and patients with PPMS (n = 15) as diagnosed by MacDonald criteria [37] were recruited for the trial. Demographic characteristics of these patients are in Table 4. All patients underwent clinical examination to assess their neurological status and disability according to the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) [38]. Median of MS duration was 3.6 years (2.0–5.0). All included MS patients had PPMS with confirmed EDSS progression at least for 12 months, according to generally accepted criteria [16], which are validated in Russia [39]. None of the PPMS patients received any DMTs or oral or intravenous courses of corticosteroids. All patients were duly informed and gave their consent to the study and signed the Information Consent.

Table 4.

Demographics of the study cohorts (medians)

| Property | Healthy (n = 15) | PPMS (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (range) | 23 a¥ (20–73) | 45 a (25–56) |

| Females, % | 44 | 40 |

| Males, % | 56 | 60 |

| BMI (range) | 24 a (17–30) | 22 a (20–27) |

¥The values in rows followed by the same letters do not differ significantly at P ≤ 0.05 level

Faecal samples were collected into 10 ml sterile faecal specimen containers and stored frozen at approximately −20 °C. Samples were transferred to the laboratory within 1 week of collection and stored at − 80 °C until used for DNA extraction. The samples were collected at least one month prior to corticosteroid treatment.

The protocol of the study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Pirogov National Science and Research Medical University. All clinical aspects of the study were supervised by a neurologist. New medicines, sorbents and/or laxatives (including magnesium salts and castor oil), as well as any diet changes, were cancelled or not started at least one week prior to faecal samples collection.

DNA extraction and sequencing

DNA was extracted from 50 to 100 mg of thawed patient faecal samples using MetaHIT protocol [40]. The bead-beating was performed using TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Germany), for 10 min at 30 Hz and 0.75 ml Zirconia/Silica Beads 0.1 mm (BioSpec Products). The quality and quantity were analysed by Nanodrop-1000 (ThermoScientific) and Qubit (Invitrogen) respectively.

The 16S rRNA gene region was amplified with the primer pair V3-V4 combined with Illumina adapter sequences [41]. PCR amplification was performed as described earlier [42]. All PCR reactions used 25 ng of faecal DNA as template and were performed in triplicates for each sample. Then the triplicates were pooled, and a total of 200 ng PCR product for each sample was pooled together and purified through MinElute Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The obtained libraries were sequenced with 2 × 300 bp paired-ends reagents on MiSeq (Illumina, USA) in SB RAS Genomics Core Facility (ICBFM SB RAS, Novosibirsk, Russia). The read data were deposited in GenBank under the study accession PRJNA565173 and the sample accession SRP221464.

Bioinformatic and statistical analyses

Raw sequences were analyzed with UPARSE pipeline [43] using Usearch v.11.0. The UPARSE pipeline included merging of paired reads; read quality filtering; length trimming; merging of identical reads (dereplication); discarding singleton reads; removing chimeras and operational taxonomic unit (OTU) clustering using the UPARSE-OTU algorithm. The OTU sequences were assigned a taxonomy using the SINTAX [44] and 16S RDP training set v.16 [45].

Taxonomic structure of thus obtained sequence assemblages, i.e. a collection of different species at one site at one time, was estimated by the ratio of the number of taxon-specific sequence reads to the total number of sequence reads, i.e. by the relative abundance of taxa, expressed as percentage.

Comparison of relative abundances of different bacterial taxa in faecal samples of the control and PPMS group was carried out by the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test for independent samples using the Statistica v.13.3 software (Statsoft, USA). The α-biodiversity indices were calculated using Usearch. All data are presented as median values.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2 with relative abundance (%) of OTUs in human faecal samples collected from healthy subjects and patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- DMT

Disease modifying therapy

- EDSS

Expanded Disability Status Scale

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- OTU

Operational taxonomic unit

- PPMS

Primary progressive multiple sclerosis

Authors’ contributions

MK collected patients’ information and samples; NN performed statistical analysis and wrote the draft of the manuscript; TA performed all laboratory analyses; AB supervised data interpretation and manuscript writing; VV provided funding, substantially revised and finalized the manuscript; MRK performed bioinformatic analyses and general supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The reported study was funded by RFBR according to the research project № 17–00-00295 (17–00-00210, 17–00-00206). Bioinformatic analysis was partially supported by the Russian State funded budget project АААА-А17–117020210021-7. The funding entities were not involved in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The read data were deposited in GenBank under the study accession PRJNA565173 and the sample accession SRP221464.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients were duly informed and gave their consent to the study and signed the Information Consent. The protocol of the study was approved by the Ethic Committee of the Pirogov Medical University (Moscow, Russia).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Madina Kozhieva and Natalia Naumova contributed equally to this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12866-019-1685-2.

References

- 1.Opazo MC, Ortega-Rocha EM, Coronado-Arrázola I, Bonifaz LC, Boudin H, Neunlist M, Riedel CA. Intestinal Microbiota Influences Non-intestinal Related Autoimmune Diseases. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:432. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li B, Selmi C, Tang R, Gershwin ME, Ma X. The microbiome and autoimmunity: a paradigm from the gut-liver axis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018;15:595–609. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2018.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wekerle H. Nature, nurture, and microbes: The development of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136(Suppl 201):22–25. doi: 10.1111/ane.12843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirby TO, Ochoa-Repáraz J. The Gut Microbiome in Multiple Sclerosis: A Potential Therapeutic Avenue. Med Sci. 2018;6:69. doi: 10.3390/medsci6030069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wing AC, Kremenchutzky M. Multiple sclerosis and faecal microbiome transplantation: are you going to eat that? Benef Microbes. 2019;10(1):27–32. doi: 10.3920/BM2018.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell JS, Spencer JI, Yates RL, Yee SA, Jacobs BM, DeLuca GC. Invited Review: From nose to gut - the role of the microbiome in neurological disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2019;45(3):195–215. doi: 10.1111/nan.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berer K, Gerdes LA, Cekanaviciute E, Jia X, Xiao L, Xia Z, Liu C, Klotz L, Stauffer U, Baranzini SE, et al. Gut microbiota from multiple sclerosis patients enables spontaneous autoimmune encephalomyelitis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(40):10719–10724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1711233114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kell DB, Pretorius E. No effects without causes: the Iron Dysregulation and Dormant Microbes hypothesis for chronic, inflammatory diseases. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2018;93(3):1518–1557. doi: 10.1111/brv.12407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanisavljević S, Dinić M, Jevtić B, Đedović N, Momčilović M, Đokić J, Golić N, Mostarica Stojković M, Miljković Đ1. Gut Microbiota Confers Resistance of Albino Oxford Rats to the Induction of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Front Immunol. 2018;9:942. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman SN, Shahi SK, Mangalam AK. The "Gut Feeling": Breaking Down the Role of Gut Microbiome in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurother. 2018;15:109–125. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0588-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imitola J. New age for progressive multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:8646–8648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1903796116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brownlee WJ, Hardy TA, Fazekas F, Miller DH. Multiple Sclerosis. 1. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: progress and challenges. Lancet. 2016;389:1336–1346. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon AJ, Corboy JR. The tension between early diagnosis and misdiagnosis in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:567–572. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brenton JN, Goldman MD. A study of dietary modification: Perceptions and attitudes of patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;8:54–57. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Correale J, Gaitán MI, Ysrraelit MC, Fiol MP. Progressive multiple sclerosis: from pathogenic mechanisms to treatment. Brain. 2017;140:527–546. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiselev I, Bashinskaya V, Baulina N, Kozin M, Popova E, Boyko A, Favorova O, Kulakova O. Genetic differences between primary progressive and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: The impact of immune-related genes variability. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;29:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2019.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellis Jeremy E., Missan Dara S., Shabilla Matthew, Moschonas Constantine, Saperstein David, Martinez Delyn, Becker Christian V., Fry Stephen E. Comparison of the prokaryotic and eukaryotic microbial communities in peripheral blood from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, and control populations. Human Microbiome Journal. 2019;13:100060. doi: 10.1016/j.humic.2019.100060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Ghezi Zinah Zamil, Busbee Philip Brandon, Alghetaa Hasan, Nagarkatti Prakash S., Nagarkatti Mitzi. Combination of cannabinoids, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD), mitigates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) by altering the gut microbiome. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2019;82:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gandy K, Zhang J, Nagarkatti P, & Nagarkatti M. The role of gut microbiota in shaping the relapse-remitting and chronic-progressive forms of multiple sclerosis in mouse models. Sci Rep. 2019;9:6923. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-43356-71/ane.13045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Jayachandran M, SSM C, Xu B. A critical review of the relationship between dietary components, the gut microbe Akkermansia muciniphila, and human health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019:1–12. 10.1080/10408398.2019.1632789. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Saadat YR, Hejazian M, Bastami M, SMH K, Ardalan M, Vahed SZ. The role of microbiota in the pathogenesis of lupus: Does it impact lupus nephritis? Pharmacol Res. 2019;139:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goda A., Maruyama F., Michi Y., Nakagawa I., Harada K. Analysis of the factors affecting the formation of the microbiome associated with chronic osteomyelitis of the jaw. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2014;20(5):O309–O317. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jumas-Bilak E, Carlier JP, Jean-Pierre H, Mory F, Teyssier C, Gay B, Campos J, Marchandin H. Acidaminococcus intestini sp. nov. isolated from human clinical samples. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:2314–2319. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64883-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu F, Guo X, Zhang J, Zhang M, Ou Z, Peng Y. Phascolarctobacterium faecium abundant colonization in human gastrointestinal tract. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:3122–3126. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren D, Li L, Schwabacher AW, Young JW, Beitz DC. Mechanism of cholesterol reduction to coprostanol by Eubacterium coprostanoligenes ATCC 51222. Steroids. 1996;61:33–40. doi: 10.1016/0039-128X(95)00173-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gérard P. Metabolism of Cholesterol and Bile Acids by the Gut Microbiota. Pathog. 2013;3:14–24. doi: 10.3390/pathogens3010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finegold SM, Lawson PA, Vaisanen M-L, Molitoris DR, Song Y, Ch L, Collins MD. Anaerofustis stercorihominis gen. nov., sp. nov., from human feces. Anaerobe. 2004;10:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melbye P, Olsson A, Hansen TH, Søndergaard HB, Bang Oturai A. Short-chain fatty acids and gut microbiota in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2019;139:208–219. doi: 10.1111/ane.13045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng Z, LongW HB, Ding D, Ma X, Zhao L, Pang X. A human stool-derived Bilophila wadsworthia strain caused systemic inflammation in specific-pathogen-free mice. Gut pathog. 2017;9:59. doi: 10.1186/s13099-017-0208-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Natividad JM, Lamas B, Pham HP, Michel ML, Rainteau D, Bridonneau C, da Costa G, van Hylckama Vlieg J, Sovran B, Chamignon C, Planchais J, Richard ML, Langella P, Veiga P, Sokol H. Bilophila wadsworthia aggravates high fat diet induced metabolic dysfunctions in mice. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2802. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05249-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loubinoux J, Bronowicki J, IAC P, Mougenel J, Le AE. Sulfate- reducing bacteria in human feces and their association with inflammatory bowel diseases. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2002;40:107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finegold SM, Downes J, Summanen PH. Anaerobe Microbiology of regressive autism. Anaerobe. 2012;18:260–262. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen J, Chia N, Kalari KR, Yao JZ, Novotna M, Paz Soldan MM, Luckey DH, Marietta EV, Jeraldo PR, Chen X, Weinshenker BG, Rodriguez M, Kantarci OH, Nelson H, Murray JA, Mangalam AK. Multiple sclerosis patients have a distinct gut microbiota compared to healthy controls. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28484. doi: 10.1038/srep28484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan Y, Zhang J. Dietary Modulation of Intestinal Microbiota: Future Opportunities in Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis and Multiple Sclerosis. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:740. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rumah KR, Vartanian TK, Fischetti VA. Oral Multiple Sclerosis Drugs Inhibit the In vitro Growth of Epsilon Toxin Producing Gut Bacterium,Clostridium perfringens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:11. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montalban X, Hauser SL, Kappos L, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, Comi G, de Seze J, Giovannoni G, Hartung HP, Hemmer B, Lublin F, Rammohan KW, Selmaj K, Traboulsee A, Sauter A, Masterman D, Fontoura P, Belachew S, Garren H, Mairon N, Chin P, Wolinsky JS, ORATORIO Clinical Investigators Ocrelizumab versus placebo in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:209–220. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1606468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen JA, Filippi M, Fujihara K, Havrdova E, Hutchinson M, Kappos L, Lublin FD, Montalban X, O'Connor P, Sandberg-Wollheim M, Thompson AJ, Waubant E, Weinshenker B, Wolinsky JS. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis. An Expanded disability status scale (EDSS) Neurol. 1983;39:291–302. doi: 10.1212/WNL.39.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Belova AN, Shalenkov IV, Shakurova DN, Boyko AN. Revised McDonald criteria for multiple sclerosis diagnostics in central Russia: sensitivity and specificity. Mult Scler J. 2014;20:1896–1899. doi: 10.1177/1352458514539405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Godon JJ, Zumstein E, Dabert P, Habouzit F, Moletta R. Molecular microbial diversity of an anaerobic digestor as determined by small-subunit rDNA sequence analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2802–2813. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2802-2813.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fadrosh Douglas W, Ma Bing, Gajer Pawel, Sengamalay Naomi, Ott Sandra, Brotman Rebecca M, Ravel Jacques. An improved dual-indexing approach for multiplexed 16S rRNA gene sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform. Microbiome. 2014;2(1):6. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Igolkina АА, Grekhov GA, Pershina EV, Samosorova GG, Leunova VM, Semenova AN, et al. Identifying components of mixed and contaminated soil samples by detecting specific signatures of control 16S rRNA libraries. Ecol Indic. 2018;94:446–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.06.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013;10:996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Edgar RC. SINTAX, a Simple Non-Bayesian Taxonomy Classifier for 16S and ITS Sequences. bioRxiv. 2016. 10.1101/074161.

- 45.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naïve Bayesian Classifier for Rapid Assignment of rRNA Sequences into the New Bacterial Taxonomy. Appl Env Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2 with relative abundance (%) of OTUs in human faecal samples collected from healthy subjects and patients with primary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Data Availability Statement

The read data were deposited in GenBank under the study accession PRJNA565173 and the sample accession SRP221464.