Abstract

Oxidative stress is a major complication in diabetes mellitus. The aim of this study was to investigate potential antioxidant activity of coenzyme Q10 (Co Q10) against hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress in diabetic rat and unraveling its mechanism of action by focusing on silent information regulator 1 (Sirt1) and nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) mRNA expression level. Furthermore, the activity of two Nrf2-dependent antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase and catalase) in the liver of diabetic rats was studied. After induction of diabetes in rats using streptozotocin (55 mg/kg), rats were divided into five groups of six each. Groups 1 and 2 (healthy control groups) were injected with isotonic saline or sesame oil; group 3 received Co Q10 (10 mg /Kg /day), group 4, as a diabetic control, received sesame oil; and group 5 was diabetic rats treated with Co Q10. Afterwards, serum and liver samples were collected, and oxidative stress markers, lipid profile, as well as the expression of Sirt1 and Nrf2 genes were measured. Diabetes induction significantly reduced expression level of Sirt1 and Nrf2 mRNAs and also declined catalase, superoxide dismutase activities, and total thiol groups levels in diabetic group in comparison to healthy controls, while a significant increase was found in the levels of malondialdehyde and lipid profile. Co Q10 treatment significantly up-regulated Sirt1 and Nrf2 mRNA levels along with an increase in catalase activity in diabetic group as compared with untreated diabetic rats. Furthermore, Co Q10 caused a marked decrease in malondialdehyde levels and significantly improved lipid profile. Our data demonstrated that Co Q10 may exert its antioxidant activity in diabetes through the induction of Sirt1/Nrf2 gene expression.

Keywords: Coenzyme Q10, Diabetes mellitus, Nrf2, Oxidative stress, Signaling, Sirt1

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus is a group of metabolic disorders characterized by chronic hyperglycemia due to insulin deficiency, insulin resistance, or both. The chronic hyperglycemia could result in severe damage, dysfunction, and failure of multiple organs, such as the liver, eyes, kidneys, nerves, heart, and blood vessels (1,2). Ample evidence has suggested that hyperglycemia accelerate the production of reactive oxygen species, leading to increased oxidative modifications of lipids, DNA, and proteins in various tissues such as heart, liver, kidney and eye (3).

Our body has integrated antioxidant systems, which include enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants that have protective role in preventing harmful effects of reactive oxygen species. Catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) are the primary defense enzymatic antioxidants and measurement of their activities has been widely used as oxidative stress markers (4).

Non-enzymatic antioxidants including glutathione (GSH), vitamins C, E, A, and coenzyme Q10 (Co Q10) as well as enzymatic antioxidants are known singlet oxygen quenching agents that disrupt chain propagation reactions (5). The activities or levels of enzymatic or non-enzymatic antioxidant systems in the cells are regulated by transcriptional, translational, and post-translational mechanisms (6). Among a panel of potential candidate genes related to oxidative stress, silent information regulator 1 (Sirt1) is mainly induced by various oxidative agents. Sirt1 is a nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide+ (NAD+)-dependent protein deacetylase and possesses remarkable antioxidative capacity (7). Sirt1 exerts its anti-oxidative effects via the activation of the nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) / antioxidant-responsive elements (ARE) pathway (8). Nrf2 is an important transcription factor that binds to ARE of genes that are involved in scavenging oxygen free radicals such as SOD, CAT, and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and GSH (9). Recent investigations demonstrated that Sirt1 protein expression and its downstream signaling is downregulated in diabetes (10). Hence, current therapeutic approaches such as antioxidant therapy for the treatment of diabetic patients have focused on the Sirt1-Nrf2 pathway (11).

Co Q10, also known as ubiquinone, is an endogenous lipid-soluble antioxidant that present in the inner membrane of mitochondria. It acts as a small electron carrier in the respiratory chain during oxidative phosphorylation (12). Furthermore, Co Q10, like other antioxidants inhibits certain enzymes involved in the formation of free radicals and thus attenuates oxidative stress and prevents the initiation and propagation of lipid peroxidation in cellular membranes (13,14).

Increasing evidence from both animal and human studies has demonstrated efficiency and antioxidative action of Co Q10 in diabetes mellitus. However, there do appear some controversies concerning the anti-oxidative abilities of Co Q10 between researchers. For example, Modi et al. have found that Co Q10 treatment inhibits lipid peroxidation induced by hyperglycemia and also could increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes like SOD and CAT, as well as GSH in diabetes leading to decrease oxidative stress (15). Whereas, Al-Thakafy et al. showed that Co Q10 treatment increased the activity of GPx and GSH concentration in erythrocytes, but decreased SOD activity (16). More interestingly, Coldiron et al. identified that treating diabetic rats with Co Q10 had no significant effect on decreased SOD, GPx activities, and levels of GSH compared to the non-diabetic control (17). Accordingly, further investigations are needed to show antioxidant capacity of Co Q10 and revealing the mechanism of its action. In this light, the present study was carried out to evaluate the potential ability of Co Q10 against hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress in diabetic rat liver and serum specimens and unravel its mechanism of action by focusing on Sirt-1-Nrf2 activation. Furthermore, the activity of two Nrf2-dependent antioxidant enzymes (SOD and CAT) in the liver of diabetic rats was studied.

For this purpose, we determined the mRNA expression level of Sirt1 and Nrf2 genes using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and malodealdehyde (MDA) level, total antioxidant capacity (TAC) as well as the activity of SOD and CAT enzymes in the serum and liver of diabetic rats treated with Co Q10.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Coenzyme Q10 was obtained from Cayman medical company (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and streptozotocin (STZ) was obtained from sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). RNX-plus reagent was purchased from Sinaclon company (Tehran, I.R. Iran) and reagents for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis were acquired from Takara (Kyoto, Japan). RT-PCR SYBR green I master mix was obtained from Yekta Tajhiz Azma Co. (Tehran, I.R. Iran). SOD kit was procured from Zell bio GmbH Company (Germany). 2,4,6-Tripyridyl-s-triazine, 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxy propane, were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). 2-thiobarbituric acid, ferric chloride (FeCl3, 6H2O), and sodium acetate were provided by Merck company (Darmstadt, Germany).

Animals

Thirty male Wistar rats (180-200 g) were provided by the animal breeding center of Arak University of Medical Sciences (Arak, I.R. Iran). They were maintained under standard conditions (12/12-h light/dark cycle, 25 ± 1 °C). Rats were given ad libitum access to food and water. The Animal Ethics Committee of Arak University of Medical Sciences approved all experiments under the ethics code number IR. ARAKMU.REC.1395.340.

Induction of diabetes

Diabetes mellitus was induced by a single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (55 mg/kg ) after an overnight fasting. Fasting blood sugar (FBS) was estimated at 72 h, and then on day 7 after the injection. Blood samples (0.1 mL) were collected from rats’ tail for estimation of FBS levels using a glucometer. Rats with blood glucose level > 250 mg/dL were considered diabetic.

Experimental design

The rats were randomly divided into five groups of six rats each. Groups 1 and 2 (as healthy control groups) were injected with isotonic saline or sesame oil 0.5 mL/kg (as vehicle of Co Q10), respectively; group 3, healthy rats received Co Q10 dissolved in sesame oil (10 mg /kg /day); group 4, diabetic rats received sesame oil; and group 5, diabetic rats received Co Q10 dissolved in sesame oil (10 mg /Kg /day). All animals received treatments orally once daily for 42 days. At the end of the experiments, animals were fasted overnight before blood sampling. Thereafter, animals were anesthetized with ketamine (50 mg/kg , intraperitoneally) / xylazine (20 mg/kg, intraperitoneally). The blood was taken directly from the heart and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min to separate the serum. Subsequently, serum samples were aliquoted and stored at -80 °C until further evaluation. At the same time, after perfusion by normal saline, liver tissues were removed and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at -80 °C until further analysis.

Biochemical assays

All serum biochemical parameters, such as FBS (GOD-POD method), triglyceride, (enzymatic method), total cholesterol (enzymatic method), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C, phosphotungstate method) were measured by colorimetric method using commercial kits (Pars Azmun, I.R. Iran). Serum low-density lipoprotein-cholestrol (LDL-C) was calculated by Friedewald’s equation as follows:

LDL − C = Total cholesterol – HDLC − VLDL (1)

The very low-density lipoprotein- cholestrol (VLDL-C) was calculated using the following formula described previously (18):

Preparation of tissue homogenates

The frozen tissues (~100 mg) were chopped into small pieces and homogenized on ice in 1 mL cold phosphate-buffered saline (pH = 7.4, 0.1 M), then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C and subsequently the supernatant was removed and used for measuring oxidative stress markers. These markers were expressed per mg wet weight of tissues.

Oxidative stress markers measurement

Oxidant/antioxidant parameters were determined in serum and tissue extracts using biochemical methods or commercial kits. TAC was assayed based on the ferric reducing ability method (19). The content of MDA was measured by thiobarbituric acid method to indicate the lipid peroxidation (20). Total thiol groups were evaluated based on Ellman’s method (21). CAT activity was assayed according to the method described by Hadwan et al. Briefly, CAT activity was assessed by incubating the sample with 65 mmol/mL H2O2, as substrate, in 60 mmol/L sodium-potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 3 min. The reaction was stopped by addition of ammonium molybdate.

Absorbance of the yellow complex was measured at 374 nm against the blank (22). SOD activity was evaluated using a commercial kit according to the manufacturers’ protocol. All assays were performed in duplicate.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from liver tissues using RNX-plus reagent according to the manufacturer’s instruction. In brief, tissue specimens were homogenized in RNX-plus (lysis buffer) using a rotary homogenizer, then total RNA was extracted using chloroform, precipitated with isopropanol, and washed with 75% ethanol. The RNA pellet was dissolved in nuclease-free water. RNA concentration was measured by Nanodrop spectrophotometer and the purity of extracted RNA was confirmed when the ratio of absorbance (260/280 nm) was within the range of 1.8-2.0. cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng RNA using the first strand cDNA synthesis kit with random hexamer and oligo (dT) primers (1:1 ratio) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Synthesized cDNA was kept at -70 °C until used.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction

RT-PCR was performed in the light cycler RT-PCR system (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Each reaction contained, 2μL of cDNA (10-fold diluted), 0.5 μL of 5 mM solutions of each of the forward and reverse primers, and 7.5 μL of 2x SYBR green master mix in a total volume of 15 μL. Cyclophilin A (cyclo A) gene was used as a housekeeping gene for normalization. Primer pairs for each gene were designed using Allel ID software. The primer sequences used shown in Table 1. All amplification reactions were performed in duplicate in each run. 2-ΔΔCT method was used to calculate the relative expression ratio (fold changes) of mRNAs in the liver tissue of test rats to those of control animals after normalizing with Cyclo A.

Table 1.

Primer sequences of used genes

| Genes | Primer sequences | |

|---|---|---|

| Sirt 1 | Forward | 5′CATCTTGCCTGATTTGTAAA3′ |

| Reverse | 5′AACTTCATCTTTGTCATACTTC3′ | |

| Nrf2 | Forward | 5′ACAACTGGATGAAGAGACCG3′ |

| Reverse | 5′TGTGGGCAACCTGGGAGTAG3′ | |

| Cyclo A | Forward | 5′GGCAAATGCTGGACCAAACAC3′ |

| Reverse | 5′TTAGAGTTGTCCACAGTCGGAGATG3′ | |

Statistical analyses

All results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. Significant differences in mean values were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with LSD’ s or Tukey’s post hoc tests where appropriate. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

Effects of coenzyme Q10 on body weight and biochemical parameters

Body weights were significantly lower in Co Q10-treated diabetic and untreated diabetic rats than control groups (P < 0.05), showing that Co Q10 treatment could not affect the body weight of animals. A significant decrease in the FBS, triglyceride, cholesterol, and VLDL-C levels were observed in diabetic rats treated with Co Q10 as compared to untreated diabetic rats (All P < 0.05). FBS, triglyceride, cholesterol, LDL, and VLDL-C levels were significantly higher in diabetic rats than control groups (All P < 0.05). The treatment of normal rats with Co Q10 did not significantly change the biochemical parameters in comparison with the control rats. These results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of biochemical parameters in rat serum. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n = 6. * Shows Significant differences compared with the healthy control, P < 0.05; and # significantly differs from diabetic control, P < 0.05.

| Parameters | Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy control | Sesame oil | Co Q10 | Diabetic control | Diabetic + Co Q10 | |

| Body weight (g) | 268.5 ± 10.4 | 253 ± 14.7 | 264 ± 3.4 | 178.16 ± 3.8* | 212.16 ± 2.8* |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 90.16 ± 2.9 | 83.5 ± 2.8 | 85.2 ± 2.3 | 535.8 ± 28.7* | 460.8 ± 28.03*# |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 76.8 ± 7.1 | 68.7 ± 3.3 | 63.5 ± 3.9 | 143.1 ± 12.9* | 83.5 ± 2.5# |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 89 ± 3.4 | 86.5 ± 4.7 | 81.5 ± 3.2 | 116 ± 6.5* | 91.9 ± 3.4# |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 39.4 ± 2.01 | 40.3 ± 2.1 | 43.6 ± 2.7 | 35.6 ± 2.02 | 38.9 ± 2.1 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 34.2 ± 2.2 | 32.4 ± 4.1 | 25.1 ± 1.3 | 51.7 ± 6.01* | 36.3 ± .03 |

| VLDL-C(mg/dL) | 15.3 ± 1.4 | 13.7 ± 0.6 | 12.7 ± 0.7 | 28.6 ± 2.5* | 16.7 ± 0.5# |

Co Q10, Coenzyme Q10; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein-cholesterol; VLDL-C, very low density lipoprotein-cholesterol.

Effect of coenzyme Q10 on oxidative stress markers

To investigate the protective effects of Q10 against oxidative stress in diabetic animals, the levels of TAC, MDA, thiol groups, and activities of SOD and CAT in the serum samples and liver tissues were measured. STZ injection caused a marked reduction in the TAC of serum (P = 0.029) and liver (P = 0.01) samples compared to control groups and Co Q10 treatment could not reverse this effect. The concentration of MDA, as an end product of lipid peroxidation, was significantly increased in the serum (P = 0.001) and liver tissue (P = 0.001) of diabetic control rats as compared to non-diabetic rats. Treatment of diabetic rats with Co Q10 remarkably diminished MDA levels in serum (P = 0.03) and liver (P = 0.022) as compared to diabetic controls. In addition, the levels of total thiol groups in serum (P = 0.009) and liver (P = 0.01) samples of diabetic group were considerably declined when comparing with control ones. Interestingly, Co Q10 treatment was not able to significantly increase the levels of total thiol groups in serum (P = 0.2) and liver (P = 0.25) of diabetic rats compared with control groups. These results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of oxidative stress markers in serum and tissue of rats. Data are presented as mean ± SEM; n = 6. * Shows Significant differences compared with the healthy control, P < 0.05; and # significantly differs from diabetic control, P < 0.05.

| Parameters | Groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy control | Sesame oil | Co Q10 | Diabetic control | Diabetic + Co Q10 | |

| TAC (serum, mM) | 0.79 ± 0.07 | 0.8 ± 0.08 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 0.53 ± 0.02* | 0.62 ± 0.07 |

| TAC (mM/g tissue) | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 6.05 ± 0.1 | 6.13 ± 0.2 | 2.61 ± 0.5* | 3.69 ± 0.3 |

| MDA (serum, nmol/mL) | 1.52 ± 0.2 | 1.51 ± 0.1 | 1.45 ± 0.2 | 4.26 ± 0.5* | 2.68 ± 0.3# |

| MDA (nmol/g tissue) | 26.79 ± 4.9 | 25.58 ± 7.7 | 22.06 ± 7.2 | 77.2 ± 9.07* | 42.9 ± 7.5# |

| SH (serum, mM) | 0.364 ± 0.03 | 0.381 ± 0.03 | 0.386 ± 0.04 | 0.211 ± 0.01* | 0.267 ± 0.02 |

| SH (mM/g tissue) | 5. 38 ± 0.1 | 5.96 ± 0.2 | 6.12 ± 0.2 | 2.63 ± 0.3* | 4.08 ± 0.5 |

Co Q10, Coenzyme Q10; TAC, total antioxidant capacity; MDA, malondialdehyde; SH, total thiol groups.

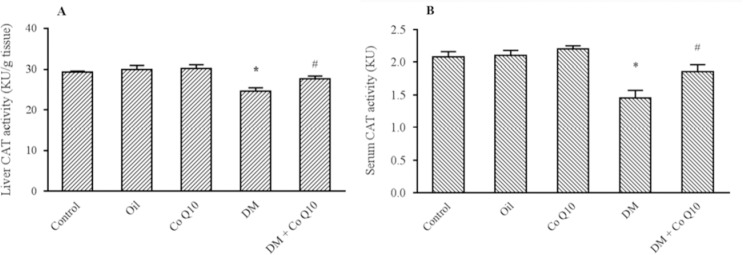

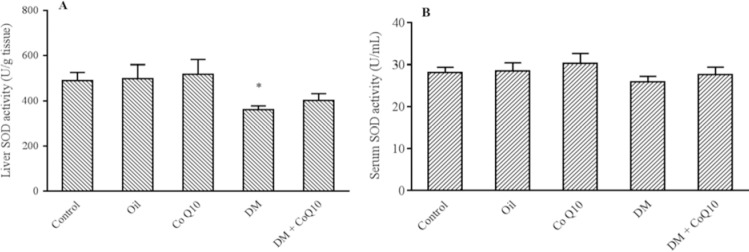

Effect of coenzyme Q10 on the activity of antioxidant enzyme

As shown in Fig. 1, a remarkable decrease in the CAT activity of serums and liver tissues was observed in diabetic rats compared with control groups (P = 0.001). The activity of this enzyme significantly induced in serum (P = 0.04) and liver tissue (P = 0.02) of Co Q10-treated rats as compared to diabetic control. As depicted in Fig. 2, liver SOD activity markedly reduced in diabetic group when comparing with healthy groups (P = 0.04), while no change was observed in the serum (P = 0.3). However, Co Q10 administration could not significantly affect the activity of SOD enzyme in serum (P = 0.4) and tissue specimens (P = 0.6) as compared to diabetic control.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of catalase activity in (A) serum (B) and liver of groups of controls, diabetic, and diabetic rats fed with Co Q10 (10 mg/kg for 6 weeks). Co Q10 treatment considerably increased catalase activity compared diabetic group. * Represents a significant difference between diabetic group and control groups (P < 0.05); # represents a significant difference between diabetic rats received Co Q10 and diabetic group (P < 0.05). Values are means ± SEM for each group. Each bar represents at least six rats. Co Q10, Coenzyme Q10; DM; diabetes mellitus.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of SOD activity in (A) serum and (B) liver of groups of controls, diabetic, diabetic and normal rats fed with Co Q10 (10 mg/kg BW for 6 weeks). Co Q10 treatment fail to increase SOD activity compared to diabetic group. * Represents a significant difference between diabetic group and control groups (P < 0.05) and # indicates a significant difference between diabetic rats received Co Q10 and diabetic group. Values are means ± SEM for each group. Each bar represents at least six rats. SOD, Superoxide dismutase; Co Q10, coenzyme Q10; DM, diabetes mellitus.

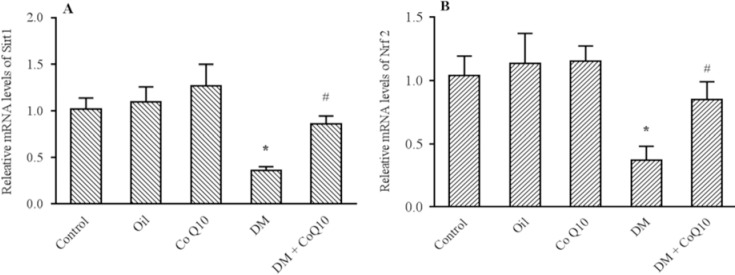

Effect of coenzyme Q10 on the expression of Sirt1 and Nrf2 in liver tissue

Figure 3 indicates the results obtained from RT-PCR. As apparent in this figure, the expression levels of Sirt1 (P = 0.002) and Nrf2 (P = 0.009) significantly decreased in the liver tissue of diabetic rats compared to control groups. The treatment with Co Q10 significantly enhanced the levels of Sirt1 (P = 0.01) and Nrf2 (P = 0.04) mRNA expression in comparison with diabetic rats.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of (A) Sirt1 and (B) Nrf2 genes expression in liver tissues of groups of controls, diabetic, diabetic, and normal rats fed with Co Q10 (10 mg/kg BW for 6 weeks) using quantitative RT-PCR. The results were normalized against the expression of the housekeeping gene, Cyclo A. Co Q10 treatment considerably increased Sirt1 and Nrf2 genes expression compared diabetic group. * Represents a significant difference between diabetic group and control groups (P < 0.05) and # indicates a significant difference between diabetic rats received Co Q10 and diabetic group. Values are means ± SEM for each group. Each bar represents at least six rats. RT-PCR, Real time polymerase chain reaction; Co Q10, coenzyme Q10; DM, diabetes mellitus.

DISCUSSION

High glucose level in diabetes leads to oxidative stress and damage to various tissues of the body due to defect in the antioxidant systems (23). Co Q10 is an endogenous antioxidant molecule that has been found to protect pancreatic β cells, liver cells, and endothelial cells against oxidative stress-induced diabetes (17). In the present study, STZ-induced diabetes in our experimental rats exhibited significant increases in serum levels of glucose and Co Q10 treatment significantly reduced the serum glucose levels in diabetic rats; nonetheless, it remained high in comparison to the healthy control group. Recent evidences propose that hyperglycemia induces the production of reactive oxygen species in diabetes (3).

Oxygen free radicals with impaired insulin signaling pathways cause insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction (24). Some studies have confirmed that Co Q10 may improve insulin cascade resulting in increased glucose uptake and inhibit gluconeogenesis in the liver (25). According to our data, diabetes induction significantly elevated the serum triglyceride, cholesterol, LDL-C, and VLDL-C in comparison with the healthy control group. Treating diabetic rats with Co Q10 showed marked decline in serum levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, and VLDL-C when comparing with diabetic control. However, treatment with Co Q10 could not affect serum levels of LDL-C and HDL-C. The mechanism of action of natural antioxidants in reducing lipids may be due to inhibition of glycosylated lipoproteins, enzymes, and proteins involved in the metabolism of lipids and lipoproteins (26). Another explanatory mechanism is that the Co Q10 increases fatty acids oxidation via AMP-activated protein kinase-dependent peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha activation (27). In our study, we observed a significant increase in MDA level along with a significant decrease in catalase activity in serum and liver of diabetic rats as well as liver SOD activity, TAC, and total thiol group level indicating an induced oxidative stress. Co Q10 supplementation considerably improved this oxidative condition by decreasing MDA concentration and increasing CAT activity. On the other hand, treatment with Co Q10 in diabetic rats was not effective in increasing TAC, thiol groups, and SOD activity compared with the healthy control group. Previous studies have also suggested that high level of free radicals leads to the formation of lipid peroxidation in STZ-induced diabetes and suggested that Co Q10 reacts with free oxygen radicals and prevents peroxidation of membrane lipids (15,28). However, the results of the present study revealed that Co Q10 supplementation can be a useful factor in reducing lipid peroxidation. Normally, two main antioxidant enzymes, CAT and SOD, protect cells from oxidative damage and regulate redox signaling within cells. Our results showed that diabetes decreased CAT activity. Nevertheless, Co Q10 supplementation in diabetic rats increased CAT activity, thereby fortified the antioxidative capacity. There are some redox-sensitive proteins in tissues that activate or block downstream molecules, including antioxidant enzyme systems that induced by oxidative conditions like diabetes. Some of these redox-sensitive proteins such as Sirt1 and Nrf2 are able to sense oxidant signals (29). Therefore, to further elucidate the upstream regulators for the induction of endogenous antioxidant enzymes, we have focused on the Sirt1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. A number of previous investigations have revealed that Sirt1 is implicated in the regulation of events that are associated with better glucose tolerance, hepatic function, and insulin sensitivity, which appear to be exerted by inducing antioxidant proteins such as Nrf2 as well as lowering pro-inflammatory cytokines (30,31). According to previous data, the expression of Sirt1 and Nrf2 has shown to be decreased in diabetes, which may ultimately lead to a decrease in antioxidant defenses (32). Our present data also is in accordance with previous ones indicating the lower expression levels of these two important genes in diabetic rats as compared with healthy controls. Here, we also presented novel gene expression findings revealing that the supplementation of diabetic rats with indicated dose of Co Q10 could result in an augmented expression of liver’s Sirt1 and Nrf2 genes in comparison to diabetic control group. A recent study has proposed that Co Q10 supplementation increases cyclic adenosine monophosphate production. cAMP is an important intracellular second messenger that is involved in the regulation of Sirt1 and AMP-activated protein kinase activity (33). We implied that the enhanced cAMP could activate AMP-activated protein kinase and increase the expression of Sirt1 protein in the liver tissue. Then, Sirt1 activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1a, which ultimately increases the expression of Nrf2 (31). This may lead to Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus, binding to the ARE promoter and the induction of heme-oxygenase 1, SOD, and CAT, three target genes of Nrf2, that play a main role in antioxidant defense against harmful effects of free radicals (34,35). However, we observed no significant alteration in the activity of SOD in our samples. The reason for this finding is not clear, but may because of the lack of enough time to enhance the total protein expression and activity in tissue samples. More interestingly, a recent study showed that SIRT3 could deacetylate SOD2, but did not alter the total protein level, to increase SOD2 activity, in oxidative injured hepatocytes (34).

CONCLUSION

Current findings indicated that Co Q10 exerts beneficial effects on diabetes-induced oxidative stress through up regulation of mRNA expression of Sirt1 and Nrf2 genes, and consequently induces antioxidant enzymes. Collectively, our data suggest a possible mechanism for anti-oxidative capacity of Co Q10 in alleviating oxidative stress in the liver tissue of diabetic rats. To reveal more details and for further confirmation of the effect of these two genes, blocking of the pathway using siRNA is suggested. However, further in vitro and in vivo studies are required to confirm the mechanism of antioxidant activity of Co Q10.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was extracted from the MSc. thesis of Fatemeh Samimi and financially suported by Vice Chancellor for Research Affairs of Arak University of Medical Sciences, Arak, I.R. Iran through the Grant No. 2704. We gratefully acknowledge technical assistance of personnels at the biochemical research laboratory of Arak University of Medical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(Suppl 1):S81–S90. doi: 10.2337/dc14-S081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sreekutty MS, Mini S. Ensete superbum ameliorates renal dysfunction in experimental diabetes mellitus. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2016;19(1):111–118. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asmat U, Abad K, Ismail K. Diabetes mellitus and oxidative stress-A concise review. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24(5):547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ighodaro OM, Akinloye OA. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J Med. 2018;54(4):287–293. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen P, Ma QG, Ji C, Zhang JY, Zhao LH, Zhang Y, et al. Dietary lipoic acid influences antioxidant capability and oxidative status of broilers. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(12):8476–8488. doi: 10.3390/ijms12128476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Q, Bhattacharya S, Pi J, Clewell RA, Carmichael PL, Andersen ME. Adaptive posttranslational control in cellular stress response pathways and its relationship to toxicity testing and safety assessment. Toxicol Sci. 2015;147(2):302–316. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfv130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu CP, Zhai P, Yamamoto T, Maejima Y, Matsushima S, Hariharan N, et al. Silent information regulator 1 protects the heart from ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation. 2010;122(21):2170–2182. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.958033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding YW, Zhao GJ, Li XL, Hong GL, Li MF, Qiu QM, et al. SIRT1 exerts protective effects against paraquat-induced injury in mouse type II alveolar epithelial cells by deacetylating NRF2 in vitro. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37(4):1049–1058. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vnukov VV, Gutsenko OI, Milyutina NP, Kornienko IV, Ananyan AA, Plotnikov AA, et al. SkQ1 regulates expression of Nrf2, ARE-controlled genes encoding antioxidant enzymes, and their activity in cerebral cortex under oxidative stress. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2017;82(8):942–952. doi: 10.1134/S0006297917080090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Kreutzenberg SV, Ceolotto G, Papparella I, Bortoluzzi A, Semplicini A, Dalla Man C, et al. Downregulation of the longevity-associated protein sirtuin 1 in insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome: potential biochemical mechanisms. Diabetes. 2010;59(4):1006–1015. doi: 10.2337/db09-1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Yuan S, Li Y, Zhang Z, Xiao W, Tang D, et al. Regulation on SIRT1-PGC-1 a/Nrf2 pathway together with selective inhibition of aldose reductase makes compound hr5F a potential agent for the treatment of diabetic complications. Biochem Pharmacol. 2018;150:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noh YH, Kim KY, Shim MS, Choi SH, Choi S, Ellisman MH, et al. Inhibition of oxidative stress by coenzyme Q10 increases mitochondrial mass and improves bioenergetic function in optic nerve head astrocytes. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4(10):e820. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.341. 12 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salehi S, Bayatiani MR, Yaghmaei P, Rajabi S, Goodarzi MT, Jalali Mashayekhi F. Protective effects of resveratrol against X-ray irradiation by regulating antioxidant defense system. Radioprotection. 2018;53(4):293–298. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bargi R, Asgharzadeh F, Beheshti F, Hosseini M, Farzadnia M, Khazaei M. Thymoquinone protects the rat kidneys against renal fibrosis. Res Pharm Sci. 2017;12(6):479–487. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.217428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Modi K, Santani DD, Goyal RK, Bhatt PA. Effect of coenzyme Q10 on catalase activity and other antioxidant parameters in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2006;109(1):25–34. doi: 10.1385/BTER:109:1:025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Al-Thakafy HS, Khoja SM, Al-Marzouki ZM, Zailaie MZ, Al-Marzouki KM. Alterations of erythrocyte free radical defense system, heart tissue lipid peroxidation, and lipid concentration in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats under coenzyme Q10 supplementation. Saudi Med J. 2004;25(12):1824–1830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coldiron AD, Jr, Sanders RA, Watkins JB. Effects of combined quercetin and coenzyme Q(10) treatment on oxidative stress in normal and diabetic rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2002;16(4):197–202. doi: 10.1002/jbt.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li C, Ford ES, Li B, Giles WH, Liu S. Association of testosterone and sex hormone-binding globulin with metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in men. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1618–1624. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groussard C, Maillard F, Vazeille E, Barnich N, Sirvent P, Otero YF, et al. Tissue-specific oxidative stress modulation by exercise: A comparison between MICT and HIIT in an obese rat model. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/1965364. Article ID 1965364, 11 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hasanein P, Sharifi M. Effects of rosmarinic acid on acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in male Wistar rats. Pharm Biol. 2017;55(1):1809–1816. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2017.1331248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dilek F, Ozkaya E, Kocyigit A, Yazici M, Guler EM, Dundaroz MR. Plasma total thiol pool in children with asthma: Modulation during montelukast monotherapy. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2016;29(1):84–89. doi: 10.1177/0394632015621563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hadwan MH. Simple spectrophotometric assay for measuring catalase activity in biological tissues. BMC Biochem. 2018;19(1):7–14. doi: 10.1186/s12858-018-0097-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motamedrad M, Shokouhifar A, Hemmati M, Moossavi M. The regulatory effect of saffron stigma on the gene expression of the glucose metabolism key enzymes and stress proteins in streptozotocin- induced diabetic rats. Res Pharm Sci. 2019;14(3):255–262. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.258494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rains JL, Jain SK. Oxidative stress, insulin signaling, and diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50(5):567–575. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amin MM, Asaad GF, Abdel Salam RM, El-Abhar HS, Arbid MS. Novel CoQ10 antidiabetic mechanisms underlie its positive effect: modulation of insulin and adiponectine receptors, Tyrosine kinase, PI3K, glucose transporters, sRAGE and visfatin in insulin resistant/diabetic rats. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89169,1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrier B, Wen S, Zigouras S, Browne RW, Li Z, Patel MS, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid reduces LDL-particle number and PCSK9 concentrations in high-fat fed obese Zucker rats. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90863,1–12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee SK, Lee JO, Kim JH, Kim N, You GY, Moon JW, et al. Coenzyme Q10 increases the fatty acid oxidation through AMPK-mediated PPARalpha induction in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. Cell Signal. 2012;24(12):2329–2336. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hajizadeh MR, Eftekhar E, Zal F, Jafarian A, Mostafavi-Pour Z. Mulberry leaf extract attenuates oxidative stress-mediated testosterone depletion in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Iran J Med Sci. 2014;39(2):123–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang K, Chen C, Hao J, Huang J, Wang S, Liu P, et al. Polydatin promotes Nrf2-ARE anti-oxidative pathway through activating Sirt1 to resist AGEs- induced upregulation of fibronetin and transforming growth factor-ß1 in rat glomerular messangial cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;399:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milne JC, Lambert PD, Schenk S, Carney DP, Smith JJ, Gagne DJ, et al. Small molecule activators of SIRT1 as therapeutics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;450:712–716. doi: 10.1038/nature06261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pfluger PT, Herranz D, Velasco-Miguel S, Serrano M, Tschop MH. Sirt1 protects against high-fat diet-induced metabolic damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(28):9793–9798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802917105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tan Y, Ichikawa T, Li J, Si Q, Yang H, Chen X, et al. Diabetic downregulation of Nrf2 activity via ERK contributes to oxidative stress-induced insulin resistance in cardiac cells in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes. 2011;60(2):625–633. doi: 10.2337/db10-1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Z, Huo J, Ding X, Yang M, Li L, Dai J, et al. Coenzyme q10 improves lipid metabolism and ameliorates obesity by regulating CaMKII-mediated PDE4 inhibition. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8253–8264. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08899-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu J, Li D, Zhang T, Tong Q, Ye RD, Lin L. SIRT3 protects hepatocytes from oxidative injury by enhancing ROS scavenging and mitochondrial integrity. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(10):e3158. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.564. 11 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maralani MN, Movahedian A, Javanmard ShH. Antioxidant and cytoprotective effects of L-Serine on human endothelial cells. Res Pharm Sci. 2012;7(4):209–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]