Abstract

Background

The ALOG (Arabidopsis LSH1 and Oryza G1) family of proteins, namely DUF640 (domain of unknown function 640) domain proteins, were found in land plants. Functional characterization of a few ALOG members in model plants such as Arabidopsis and rice suggested they play important regulatory roles in plant development. The information about its evolution, however, is largely limited, and there was no any report on the ALOG genes in Petunia, an important ornamental species.

Results

The ALOG genes were identified in four species of Petunia including P. axillaris, P. inflata, P. integrifolia, and P. exserta based on the genome and/or transcriptome databases, which were further confirmed by cloning from P. hybrida ‘W115’ (Mitchel diploid), a popular laboratorial petunia line susceptible to genetic transformation. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that Petunia ALOG genes (named as LSHs according to their closest Arabidopsis homologs) were grouped into four clades, which can be further divided into eight groups, and similar exon-intron structure and motifs are reflected in the same group. The PhLSH genes of hybrid petunia ‘W115’ were mainly derived from P. axillaris. The qPCR analysis revealed distinct spatial expression patterns among them suggesting potentially functional diversification. Moreover, over-expressing PhLSH7a and PhLSH7b in Arabidopsis uncovered their functions in the development of both vegetative and reproductive organs.

Conclusions

Petunia genome includes 11 ALOG genes that can be divided into eight distinct groups, and they also show different expression patterns. Among these genes, PhLSH7b and PhLSH7a play significant roles in plant growth and development, especially in fruit development. Our results provide new insight into the evolution of ALOG gene family and have laid a good foundation for the study of petunia LSH gene in the future.

Keywords: Petunia, ALOG genes, DUF640 domain, Transcription factor, Expression pattern, Plant development

Background

Transcription factors (TFs) are involved in activation and/or inhibition of transcription in respond to a variety of endogenous and environmental signals, and play a crucial role in the regulation of many developmental processes and defensive responses in plants. According to the regulatory function, mechanism of action, and the sequence homology of their DNA binding domains (DBD) and other conserved motifs, TFs can be divided into different categories [1]. Usually, there are two mechanistic classes of transcription factors: basal and specific TFs [2]. Different from the highly conserved basal TFs, which are ubiquitous in all organism and necessary for transcription to occur, specific TFs have great diversity in structure and phyletic distribution [3]. For example, ALOG-domain proteins, a family of plant specific TFs, controls plant growth and development in many aspects [4–9].

The ALOG family was named after Arabidopsis LSH1 and Oryza G1, the first two family members identified from eudicots and monocots, respectively. A highly conserved domain corresponding to DUF640 in the protein-family (Pfam) database (Pfam accession number IPR006936) was identified in ALOG family [4, 5]. DUF families encode functionally uncharacterized proteins, but the ALOG/DUF640 proteins had been suggested to function as specific TFs in plant based on the characteristics of sequence-specific DNA binding, transcriptional regulatory activity, nuclear location, and homodimer formation [5, 7, 10, 11]. With 4 all-α helices and additional insertion of a zinc ribbon, ALOG domain was predicted to be a N-terminal DNA-binding domain originated from the XerC/D-like recombinases of a new category of DIRS-1-like retroposons [10]. Furthermore, ALOG-like domains also exist in certain plant defense proteins, where they may function as DNA sensor [10, 12].

Up to now, our knowledge on the evolution and function of ALOG proteins is very limited. Only a few genes have been studied in the ALOG family, which indicate they play a key role in developmental regulation [4–8, 13, 14]. AtLSH1 was the first ALOG gene identified in the plant kingdom, which was cloned from a dominant mutant (lsh1-D) of Arabidopsis that displays hypersensitive to uninterrupted far-red, blue and red light and produces shorter hypocotyl than wild-type plants. AtLSH1 mediates light regulation during seedling development, which functionally depends on phytochromes [4]. Recent studies have also revealed the function of ALOG domain genes in the establishment of organ boundaries [7, 15]. For instance, AtLSH3 (ORGAN BOUNDARY1, OBO1) and AtLSH4 (OBO4) genes are expressed in the boundary cells of various lateral organs, including cotyledons, leaves and floral organs, which is directly up-regulated by CUC1 (CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1), a NAC protein that plays central roles in embryonic SAM (shoot apical meristems) formation and specification of the shoot organ boundaries [7, 16, 17]. Over-expressing OBO1 disrupts numbers and size of petals and causes petal-stamen fusion, while ablation of the OBO1-expressing cells leads to loss of the shoot apical meristems and lateral organs; ectopic expression of OBO4 in the shoot apex results in inhibition of leaf development and formation of extra shoots or shoot organs within flowers [7, 15, 16]. These results indicate that AtLSH3 and AtLSH4 may inhibit organ differentiation in the boundary regions [16–18].

Studies in other species revealed that ALOG family proteins mediate the regulation of inflorescence architecture and flower organ development. Long sterile lemma (G1) specifies the identity of sterile lemma in rice by repressing the homeotic transformation of the sterile lemma to the regular lemma [5]. Another homolog of OsG1 in rice, TH1 (TRIANGULAR HULL1), also known as BSG1 (BEAK-SHAPED GRAIN1)/BLS1 (BEAK LIKE SPIKELET1)/BH1 (BEAK-SHAPED HULL1)/AFD1 (ABNORMAL FLOWER AND DWARF1), regulate cell extension of the lemma and palea to determine grain shape and size [11, 19–21], which may function as a transcription repressor and regulate downstream hormone signal transduction and starch/sucrose metabolism related genes [11, 20, 21]. Contrast to G1 and TH1, TAWAWA1 (TAW1), the third rice ALOG gene, is a specific regulator of meristems activity and regulates inflorescence architecture by maintaining an indeterminate fate of inflorescence meristems and inhibiting the phase change to spikelet meristems identity, probably through up-regulating SVP-like genes such as OsMADS22, OsMADS47, and OsMADS55 [6, 22]. Similarly, an ALOG protein in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), TERMINATING FLOWER (TMF), affects inflorescence organization by suppressing the inflorescence meristems to adopt floral fate [8]. In the tmf mutant, the primary SAMs terminate as single flowers, instead of forming sympodial inflorescence meristems or vegetative shoot meristems, which is partly due to precocious expression of FALSIFLORA (FA) and ANANTHA (AN), the orthologous genes of Arabidopsis LFY and UFO, respectively [8].

Petunia is an important ornamental species and an ideal model for comparative study of gene functions attributed to the characteristics of highly efficient genetic transformation, easy of cultivation and propagation [23–25]. Considering the limitation of evolution and function of ALOG proteins, petunia can be an ideal material to conduct in-depth study. Recently, genome sequencing was accomplished in P. inflata and P. axillaris [26], which offer an effective basis to investigate the gene family on a genome-wide scale. In this study, the first characterization of the entire ALOG gene family was performed in Petunia, including the analysis of gene structure, motif composition, phylogenetic classification and expression pattern. As a result, we identified 11 ALOG domain genes in Petunia and confirmed these genes by cloning from P. hybrida line W115. Multiple alignments between PhLSHs and homologous genes from four wild Petunia species suggested that P. axillaris was the major paternal donor of PhLSHs. In addition, the function of PhLSH7a and PhLSH7b was characterized by over-expressing in Arabidopsis plants. The results have laid a solid foundation for further elucidating the functions of ALOG-domain genes in petunia.

Results

Identification of ALOG genes in Petunia

Petunia ALOG genes were identified by the HMM profile for the DUF640 domain (PF04852) search and tBLASTx (translated nucleotide to translated nucleotide) search with Arabidopsis and rice ALOG proteins against the genomic and transcriptomic databases of P. inflata and P. axillaris [27, 28], respectively. As a result, 11 ALOG genes were identified in P. axillaris, named PaLSHs (Additional file 1), and 13 ALOG genes were identified in P. inflata, named PiLSHs (Additional file 2). These genes were numbered based on their homologs in Arabidopsis. In P. inflata, the three PiLSH5 genes have identical coding sequences, and so only one was used in the subsequent analysis.

To identify the complete open reading frame (ORF) and the exon-intron distribution of the Petunia LSHs, we designed the gene-specific primers (Additional file 3) to amplify the full-length coding sequences (CDS) and their genomic DNA (gDNA) sequences of PhLSHs from W115. Finally, all putative petunia LSH genes were isolated and confirmed by sequencing (Table 1).

Table 1.

LSH genes in P. hybrida ‘W115’ (Mitchel diploid)

| Gene name | NCBI Accession number | CDS length (bp) | Gene length (bp) |

Protein length (aa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhLSH1 | MK179267 | 585 | 1112 | 194 |

| PhLSH2 | MK179268 | 483 | 483 | 160 |

| PhLSH3a | MK179269 | 594 | 976 | 197 |

| PhLSH3b | MK179270 | 576 | 576 | 191 |

| PhLSH4 | MK179271 | 567 | 567 | 188 |

| PhLSH5 | MK179272 | 696 | 794 | 231 |

| PhLSH7a | MK179273 | 582 | 582 | 193 |

| PhLSH7b | MK179274 | 555 | 555 | 184 |

| PhLSH10a | MK179275 | 540 | 540 | 179 |

| PhLSH10b | MK179276 | 534 | 534 | 177 |

| PhLSH10c | MK179277 | 516 | 516 | 171 |

Sequence characteristics of Petunia ALOG genes

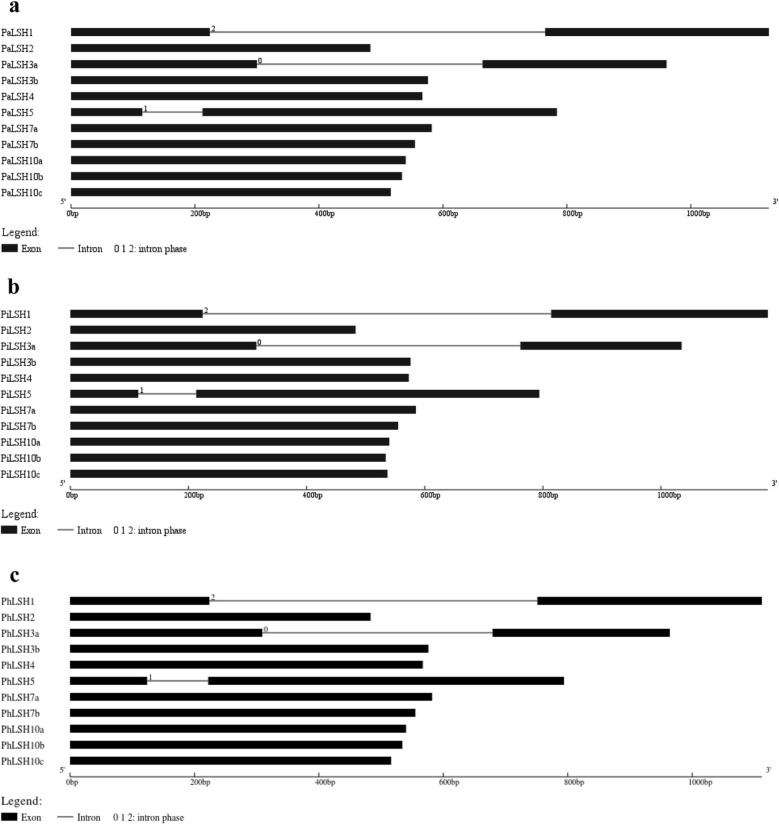

Sequence analysis showed that the gene length of Petunia LSHs vary from 483 bp (PaLSH2) to 1126 bp (PaLSH1) in P. axillaris (Additional file 1), 483 bp (PiLSH2) to 1180 bp (PiLSH1) in P. inflata (Additional file 2), and 483 bp (PhLSH2) to 1112 bp (PhLSH1) in P. hybrida (Table 1). The CDS length of PhLSHs vary from 483 bp (PhLSH2) to 696 bp (PhLSH5), with corresponding length of PhLSH proteins from 160 to 231 aa (Table 1). Exon-intron analysis indicated that PhLSH1, PhLSH3a, and PhLSH5 had two exons and one intron, while the other 8 genes only have a single exon without an intron (Fig. 1c), consistent with the results predicted by the genomic data of PiLSHs and PaLSHs (Fig. 1a, b).

Fig. 1.

Gene structures of PaLSHs (a), PiLSHs (b) and PhLSHs (c). The black block indicates the exons, and the gray thin line indicates the introns. The intron phases were represented by 0, 1 and 2

Phylogenetic analysis of PhLSH proteins

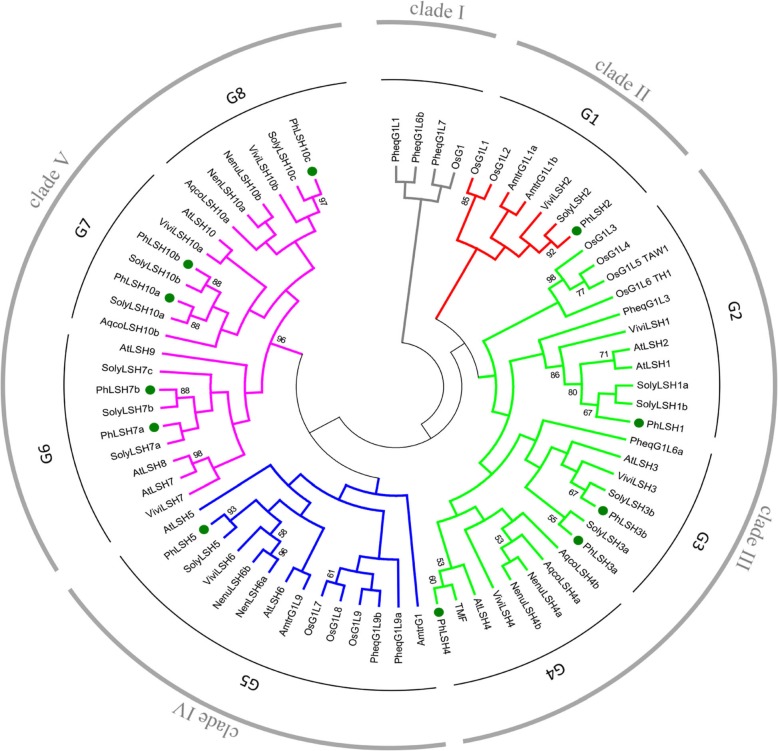

The phylogenetic relationship between PhLSHs and homologous genes in other species will contribute to reveal the evolution of ALOG family and gene function in petunia. Therefore, we constructed a Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree with the ALOG proteins identified from representative species within different clades of angiosperms (Additional file 4). As a result, the ALOG proteins were divided into five clades: clade I (OsG1-like) includes proteins only from monocots, clade II (OsG1L1/2-like) includes proteins from Amborella trichopoda, grape, tomato and petunia, clade III and IV (AtLSH1/2/3/4-like and AtLSH5/6-like, respectively) include protein from almost all species, while clade V (AtLSH7/8/9/10-like) only includes proteins from eudicots (Fig. 2). The petunia LSH genes were distributed in clade II-V, which can be further divided into 8 groups: Group 1 (G1) including PhLSH2; Group 2 (G2) including PhLSH1; Group 3 (G3) containing PhLSH3a and PhLSH3b; Group 4 (G4) containing PhLSH4; Group 5 (G5) containing PhLSH5; Group 6 (G6) containing PhLSH7a and PhLSH7b; Group 7 (G7) containing PhLSH10a and PhLSH10b, and Group 8 (G8) containing PhLSH10c (Fig. 2). Both the redundancy of function and divergence of the LSH gene family could be reflected in this classification. Lineage-specific duplication can be revealed from this phylogenetic tree. In plants, duplication of some LSH genes appears to occur very late. For example, duplication of genes in Group V and VI had occurred after the separation of the monocot and dicot.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the ALOG proteins in different species. Phylogenetic analysis based on the conserved ALOG domains (130 aa) of a total of 73 protein sequences. Species abbreviations are as follows. Ph: Petunia hybrida; At: Arabidopsis thaliana; Os: Oryza sativa; Vivi: Vitis vinifera; Amtr: Amborella trichopoda; Phap: Phalaenopsis aphrodite; Nenu: Nelumbo nucifera; Aqco: Aquilegia coerulea and Soly: Solanum lycopersicum. The tree was generated by the Maximum likelihood (ML) method in MEGA 6.0 with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Letters outside of the tree indicate the defined groups

Origin of PhLSH genes

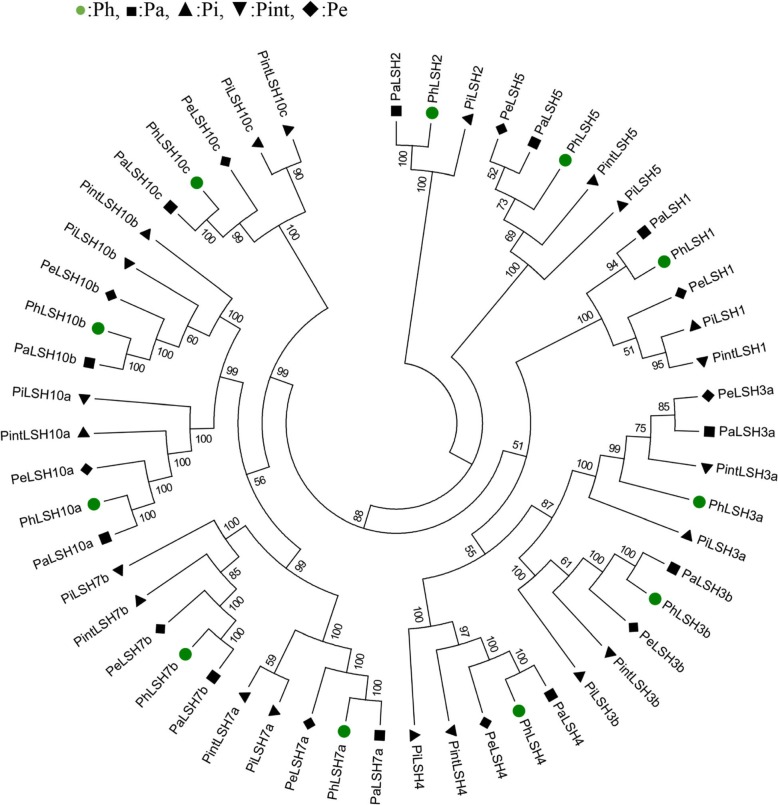

Multiple sequence alignment based on the CDS of LSHs in W115 and four Petunia wild species (P. integrifolia, P. exserta, P. axillaris and P. inflata) was used to determine the origin of PhLSH genes, i.e. which species was the donor of PhLSH genes. Only 10 of the 11 LSH genes could be identified from the Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly (TSA) database of P. integrifolia and P. exserta (Additional file 5) [29, 30]. The orthologs of PhLSH2 are not recognized in P. integrifolia and P. exserta and so not included in the subsequent analysis. A phylogenetic relationship constructed with CDS of all identified Petunia LSH genes shows that 9 of 11 PhLSH genes, including PhLSH1, PhLSH2, PhLSH3b, PhLSH4, PhLSH7a, PhLSH7b, PhLSH10b, PhLSH10b, and PhLSH10c, are grouped with orthologous genes from P. axillaris (Fig. 3), suggesting that PhLSH genes might mainly originate from P. axillaris. Further alignment and comparison of the coding sequences of these LSHs genes indicates that 5 of 11 PhLSHs (PhLSH4, PhLSH7a, PhLSH7b, PhLSH10a, PhLSH10c) are identical to their orthologous PaLSHs (Additional file 6); moreover, PhLSH4, PhLSH7a, PhLSH7b and PhLSH10c are different at least for one nucleotide from PiLSHs, PintLSHs and PeLSHs, confirming they come from P. axillaris. The CDS of PhLSH10a is the same as those of PiLSH10a, PintLSH10a, and PeLSH10a, but its 3’UTR sequence is identical to that of PaLSH10a and different from those of PeLSH10a and PintLSH10a (data not shown), indicating that PhLSH10a also come from P. axillaris. The coding sequences of PhLSH1 and PhLSH10b contain only one-nucleotide differences compared to those of PaLSH1 and PaLSH10b but at least four-nucleotide differences in comparison to the orthologs from other three species, suggesting that PhLSH1 and PhLSH10b may also originate from P. axillaris. The sequences of PhLSH3a and PhLSH5 show substantial differences in all four species but have more similarity to the orthologs of P. exserta, indicating that they may have originated from P. exserta.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree for the CDS of petunia LSHs. Ph, P. hybrida; Pa, P. axillaris; Pi, P. inflata; Pint, P. integrifolia; and Pe, P. exserta. The tree was constructed by MEGA 6.0 using Maximum Likelihood method based on the GTR + G + I model with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 50% bootstrap replicates are collapsed

ALOG domains and motifs of PhLSHs

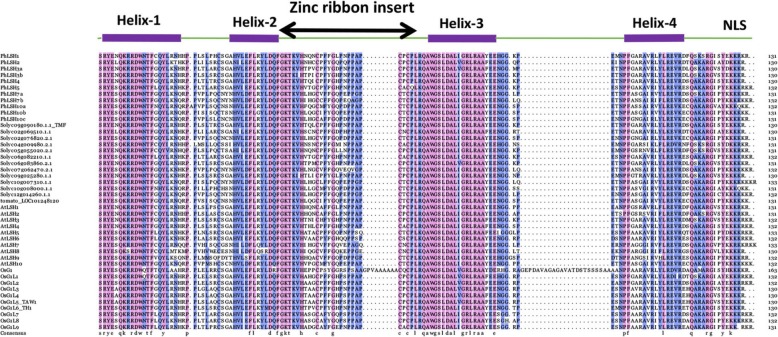

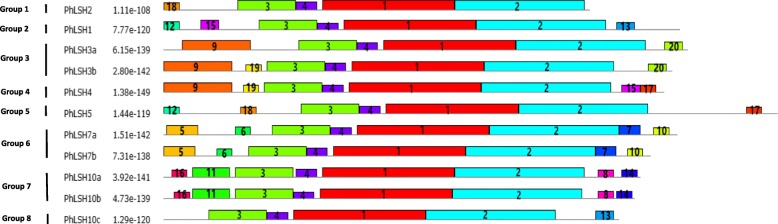

To investigate the sequence conservation and divergence of petunia ALOG members, multiple sequence alignment was carried out and conserved motifs were identified in the 11 PhLSH proteins. The results demonstrate that all PhLSH proteins contain a conserved ALOG domain in the middle region, which consists of four helixes with a zinc ribbon insert and a nuclear location signal (NLS) sequence (Fig. 4), however, the similarity of the N- and C-terminal sequences is very low (Additional file 7), which is consistent with previous reports in other species [29, 31, 32]. Motif analysis shows that a total of 20 motifs are present in PhLSH proteins and the number of motifs in each protein varies from 5 to 8 (Fig. 5, Additional file 8). Motifs 1–4 constitute the ALOG domain and exist in all PhLSHs, while other motifs show group- or member-specific distribution. For instance, motif 9 appears only in the Group 3 and Group 4 proteins PhLSH3a/3b/4; motifs 5–7 and 10 only exist in the Group 6 proteins PhLSH7a/7b; motifs 8, 11, 14, and 16 are specific to the Group 7 proteins PhLSH10a and PhLSH10b.

Fig. 4.

Characteristics of the ALOG domains. Multiple alignments of the highly conserved ALOG domains (130 aa) of 11 PhLSH proteins, 13 SlyLSH proteins, 10 AtLSH proteins, and 10 OsG1-like proteins. The conserved ALOG domain included a zinc ribbon insert structure and NLS. Sequences were colored based on 75% consistency. The absolutely conserved residues are shown in light purple

Fig. 5.

Motifs in the PhLSH proteins predicted by MEME

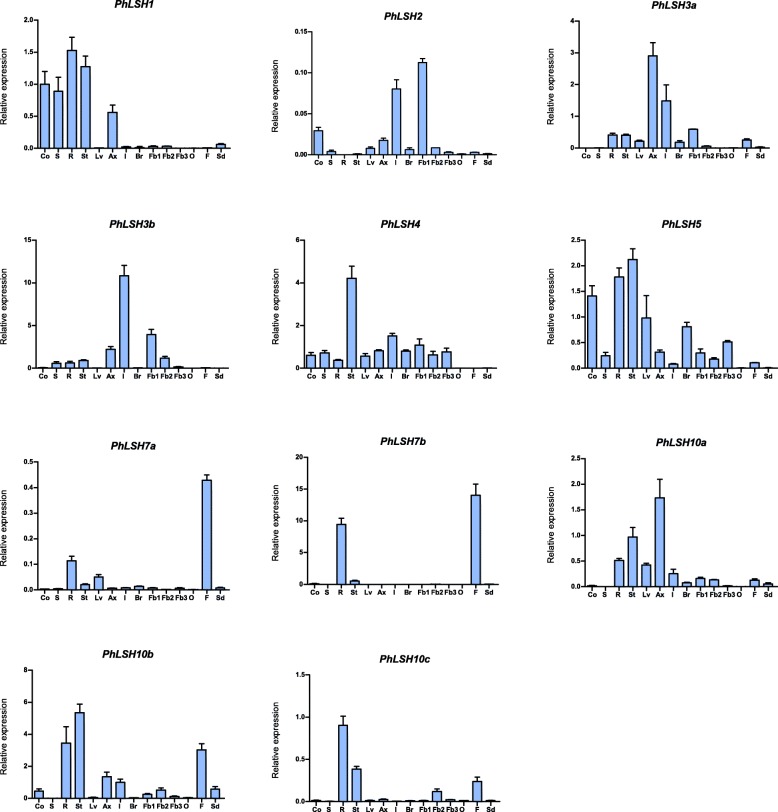

Spatial expression of PhLSHs

Expression analysis of PhLSHs in different organs by qPCR shows that PhLSH genes were expressed in different patterns among various tissues (Fig. 6, Additional file 9). Among them, the most specific expression is the members belonging to Group 6, PhLSH7a and PhLSH7b, both of which are only significantly expressed in roots and fruits, whereas the expression level of PhLSH7b is much higher (about 100 folds) than that of PhLSH7a. In contrast, PhLSH4 and PhLSH5 show more ubiquitous expression in most tissues with the highest expression in stems. Different from PhLSH4, however, which is not expressed in fruits and lower expressed in cotyledons and roots, PhLSH5 has low expression in fruits and relatively high expression in cotyledons and roots. PhLSH3a and PhLSH3b belong to the same group but have differential expression profile. PhLSH3a shows the highest expression level in axillary buds followed by inflorescences, while PhLSH3b has the highest expression in inflorescences followed by young flower buds, and that the expression level of PhLSH3b was much higher than that of PhLSH3a. Similarly, the expression patterns of the Group 7 members (PhLSH10a and PhLSH10b) are different. PhLSH10a is mainly expressed in axillary buds followed by stems, while PhLSH10b is mainly expressed in roots, stems, seedling, and fruits. PhLSH10c, a close paralogs of PhLSH10a/10b, is only significantly expressed in roots. PhLSH1 has very low expression levels in all reproductive organs, but with high expression levels in the vegetative organs (except for leaves). PhLSH2 is the member with the lowest expression levels compared to other genes, mainly expressed in inflorescences and young flower buds.

Fig. 6.

Expression analysis of PhLSHs by qPCR. Co, cotyledons; S, seedlings; R, roots; St, stems; Lv, leaves; Br, bracts; Ax, axillary buds; I, inflorescences; Fb1–3, flower buds (0.1, 0.5, and 6 cm, respectively); O, ovaries; F, fruits, and Sd, seeds. PhEF1α was used as reference gene for the transcript level. For each tissue, three biological replicates were used to calculated the mean values ± SD (standard deviation) with the 2−ΔΔCT method. The expression of PhLSH1 in Co was used as calibrator

Function of PhLSH7a and PhLSH7b in Arabidopsis

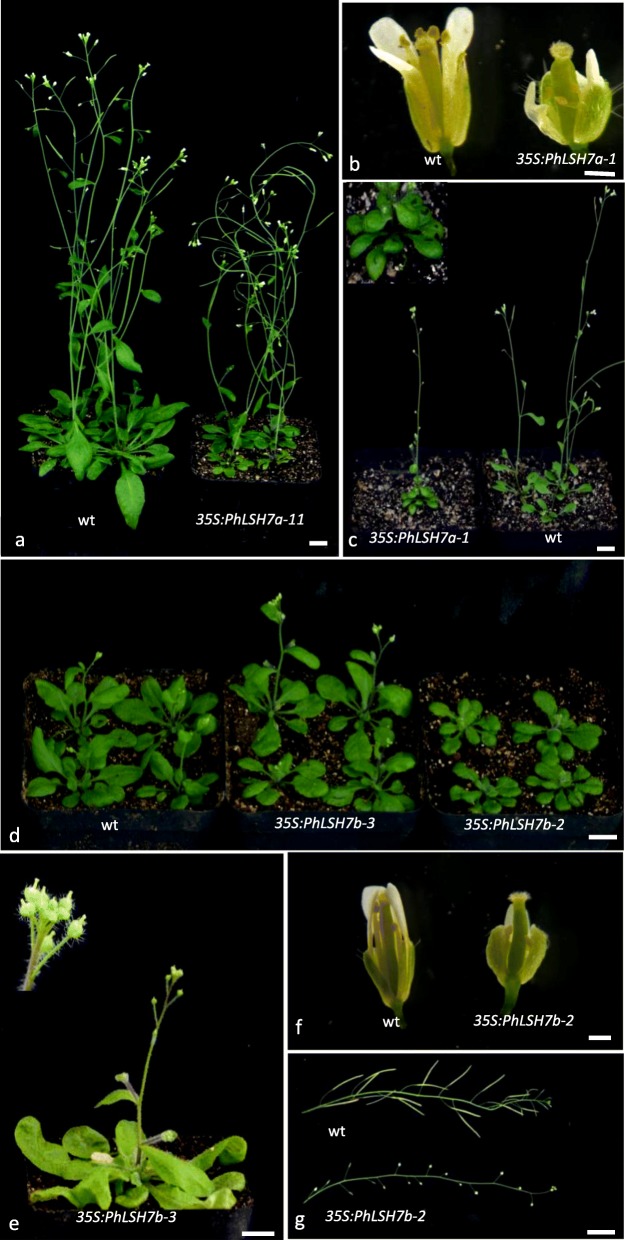

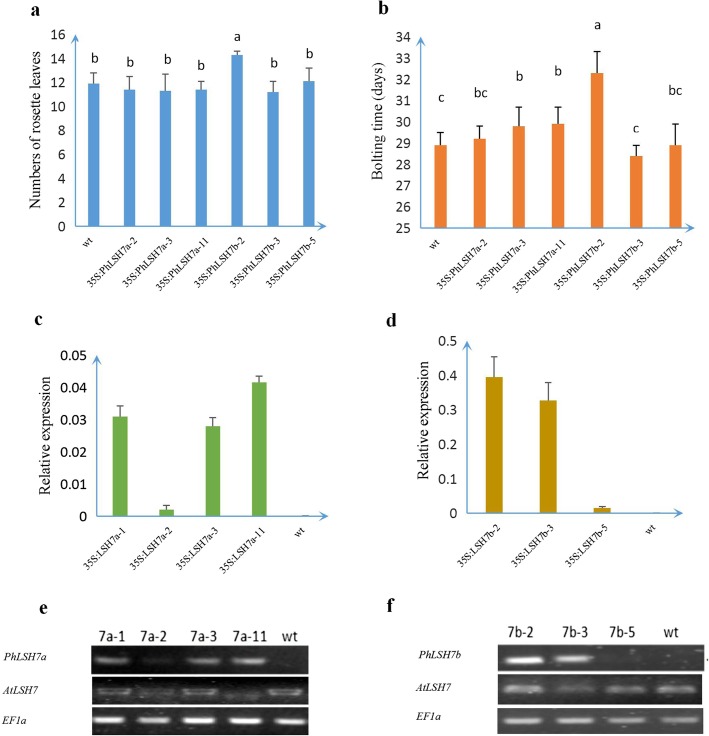

Over-expression of PhLSH7a and PhLSH7b in Arabidopsis shows that both genes have remarkable effects on the vegetative and reproductive growth of transgenic plants. There were significant phenotypic changes in PhLSH7a/7b-overexpressing lines, including small round leaves (Fig. 7a, c, d), late flowering (Fig. 7d), and deformed flowers such as abnormal petals and exposed pistil out of an unopened flower (Fig. 7b, e, f). In particular, there is no progeny can be obtained from the lines with strong phenotype (35S:PhLSH7a-1 and 35S:PhLSH7b-2) by self-pollinating (Fig. 7c, g). However, when the wild-type plants were used as pollen donors to cross with 35S:PhLSH7b-2, some small siliques and few seeds can be harvested, which suggests that the male and female fertility of transgenic plants were both significantly decreased, and infertility of the 35S:PhLSH7b-2 line may mainly due to the sterile pollen. Unfortunately, we failed to obtain seeds from 35S:PhLSH7a-1 even after pollinated with wild-type pollen. Other 35S:PhLSH7a transgenic lines with weaker phenotype still show small round leaves (Fig. 7a). In addition, the progenies of 35S:PhLSH7b-2 show late flowering compared to wild type and other transgenic lines. RT-PCR and qPCR showed that phenotype changes were largely related to the expression level of exogenous transgene instead of endogenous gene (Fig. 8; Additional file 10).

Fig. 7.

Phenotypes of the 35S:PhLSH7a and 35S:PhLSH7b transgenic Arabidopsis plants. a The 35S:PhLSH7a-11 transgenic plants (right) show small and round leaves compared to the wild-type (left). b A flower of wild type (wt, left) and 35S:PhLSH7a-1 (right) show deformed flowers of 35S:PhLSH7a transgenic plants in which one petal and one sepal were removed. c The 35S:PhLSH7a-1 transgenic plants (left) show small and round leaves compared to wt (right). The picture in the upper left is a close-up of small and round leaves. d The 35S:PhLSH7b transgenic plants (35S:PhLSH7b-2 and 35S:PhLSH7b-3) show small round leaves compared to wt (left), and 35S:PhLSH7b-2 (right) is late flowering compared to wt (left) and 35S:PhLSH7b-3 (middle). e The flowers of 35S:PhLSH7b-3 show the deformed flowers with abnormal petals and exposed pistil out of an unopened flower. The picture in the upper left is a close-up of deformed flowers. f A flower of wt (left) and 35S:PhLSH7b-2 (right) show deformed flowers of 35S:PhLSH7b transgenic plants in which one petal and one sepal were removed. g Fruits of 35S:PhLSH7b-2 (right) show a sterile phenotype compared to wt (left). Bars: 10 mm (a, c, d, e, and g), 0.5 mm (b and f)

Fig. 8.

Phenotype and RT-PCR analysis of transgenic Arabidopsis plants. a Comparison of rosette leaves (RL) in wt and transgenic lines shows that 35S:PhLSH7b-2 contains more rosette leaves than others. The letters indicate the result of statistical differences. b Comparison of flowering time (FT) in wt and transgenic lines shows that 35S:PhLSH7b-2 is later flowering than others. The letters indicate the result of statistical differences. c, d qPCR analysis shows the expression level of transgenes in wt and transgenic Arabidopsis lines. 35S:PhLSH7a-11 has higher expression level than other 35S:PhLSH7a lines (c); 35S:PhLSH7b-2 has higher expression level than other 35S:PhLSH7b lines (d). The phenotype changes were largely related to the expression level of transgenes (Fig. 7). e, f Semi quantitative RT-PCR analysis shows the expression level of transgenes in wt and transgenic Arabidopsis lines consistent with the results of qPCR. There is no any interference with the two endogenous genes, AtLSH7/8 (AtLSH8 cannot be detected, so its semi-quantitative results are not displayed)

Discussion

Evolution of ALOG gene family

ALOG family plays important roles in plant morphogenesis and organ development. The ALOG domain has been proposed to be derived from the XerC/D-like recombinases of a new category of DIRS-1-like retroposons and was probably acquired during the evolution of streptophyte-clade plants [10]. According to recent studies, the evolution of the ALOG domain is dominated by lineage-specific duplication and these expansions seem to have occurred after the separation of monocot and dicot lineages [10, 31]. The evolutionary history of the ALOG family over plant diversification, however, still remains largely unclear. Recently, Xiao et al. [31] carried out a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the ALOG family with genes from basal land plants, monocots, and eudicots, which showed that the genes from different plant lineages clustered independently. Among the grass lineage, three clades were present: GrassALOG1 including rice G1 (OsG1) and OsG1L1/2, GrassALOG2 including OsG1L3/4/5, and GrassALOG3 including OsG1L6/7/8/9; while the ALOG genes of eudicot lineage were further divided into four clades: euALOG1 (AtLSH1/2/3/4), euALOG2 (without Arabidopsis gene), euALOG3 (AtLSH7/8/9/10), and euALOG4 (AtLSH5/6). In our phylogenetic analysis, an unrooted tree was constructed with the ALOG domains of 73 proteins from 9 representative species belonging to different evolutionary clades. The results indicated these proteins could be divided into five clades (Fig. 2), which is similar to the results reported by Iyer and Aravind [10] but different from the results of Xiao et al. [31]. Phylogenetic analysis with seven species including a basal land plant species (Physcomitrella patens), two eudicots (Arabidopsis and Populus trichocarpa) and four grasses divided the ALOG proteins into six distinct clusters [29]: cluster A, B, and C are Physcomitrella and monocot-specific, including OsG1L1/2, OsG1 and OsG1L3/4/5/6, respectively; cluster D and F are eudicot-specific, including AtLSH7/8/9/10 and AtLSH1/2/3/4, respectively; cluster E contains proteins of both grasses (OsG1L7/8/9/10) and eudicots (AtLSH5/6). These results indicate that the evolutionary history of the ALOG proteins appears to be complicated, and we need more sequences and studies to clarify it.

According to our phylogenetic tree, petunia LSH genes can be divided into four clades consisting of 8 groups (Fig. 2): Group 1 contains PhLSH2 and orthologs from basal angiosperm, monocots, and core eudicots, but not Arabidopsis and basal eudicots; Group 2 contains PhLSH1 and orthologs from P. aphrodite and core eudicots; Group 3 contains PhLSH3a/3b and orthologs of P. aphrodite and core eudicots; Group 4 contains PhLSH4 and orthologs of eudicots; Group 5 contains PhLSH5 and orthologs of all other species except for A. coerulea; Group 6 contains PhLSH7a/7b and orthologs of other core eudicots; Group 7 contains PhLSH10a/10b and orthologs from all other eudicots except for N. nucifera; Group 8 contains PhLSH10c and orthologs from all other eudicots except for Arabidopsis. This result is consistent with the classification of LSH genes in crucifer [30] and indicates that the ALOG family has undergone multiple times of independent duplication and/or loss events during the evolution of angiosperm. Furthermore, species-specific late expansions of ALOG genes in Solanaceae can be found from the phylogenetic tree, such as PhLSH7a/7b and PhLSH10a/10b gene pairs. In P. inflata, we found three PhLSH5 orthologs that have complete identical coding sequences (Additional file 2), which may also come from very recent duplication in this species.

Expression and functions of ALOG proteins in petunia

Currently, the functions of ALOG genes are only available for a few members in Arabidopsis, rice, and tomato. It is generally believed that gene function is closely related to their expression characteristics. So, we investigated the spatial expression profile of petunia LSHs. Consequently, PhLSH genes showed divergent expression patterns with different tissue specificity (Fig. 6), suggesting that they may have diverse functions in regulating the development of these organs.

PhLSH1 is proved to be the orthologs of Arabidopsis AtLSH1/2 genes (Fig. 2). In Arabidopsis, AtLSH1 is expressed in cotyledons, hypocotyls, shoot apices, and roots (especially in lateral root primordium), and it is functionally dependent on phytochrome to mediate light regulation of seedling development [4]. Similar to AtLSH1, PhLSH1 is expressed mainly in the vegetative organs including seedlings, cotyledons, roots, stems, and axillary buds (Fig. 6), implying it may have comparable functions to AtLSH1. Different from the situation in Arabidopsis, which contains two very close paralogs AtLSH1 and AtLSH2 that may result in functional redundancy, petunia contains only one gene in this group, so functional characterization of PhLSH1 will be easier. PhLSH2 has no orthologs in Arabidopsis or functionally known group members, and that it has very low expression levels in all tissues compared to other PhLSH genes, so its function maintains elusive. It may attribute to the low expression for the fact that no PhLSH2 orthologs was identified in P. integrifolia and P. exserta.

PhLSH3a/3b and PhLSH4 are the orthologs of AtLSH3 and AtLSH4, respectively. In the same clade, it also includes rice TAW1 and tomato TMF, two functional characterized genes. AtLSH3 and AtLSH4 are both expressed in boundary cells of various lateral organs including cotyledons, leaves, and floral organs, which may inhibit organ differentiation in the boundary regions [7, 15]. In contrast, petunia PhLSH3a/3b and PhLSH4 show different expression patterns, in which PhLSH3a mainly expressed in axillary buds followed by inflorescences, PhLSH3a mainly in inflorescences, and PhLSH4 mainly in stems (Fig. 6), suggesting that petunia PhLSH3a/3b/4 genes may have different functions from their orthologs in Arabidopsis. TMF, an orthologous gene of PhLSH4 in tomato, is expressed predominantly in the shoot apex, with high expression in vegetative stages of the primary shoot meristems (PSM) and the sympodial vegetative meristems (SYM), slightly decreased expression in the reproductive transition meristems, and weak expression in the floral meristems (FM), sympodial inflorescence meristems (SIM), and young leaves [8]. TMF synchronizes the flowering transition and flower formation by timing AN activation, which has a key role in determining simple versus complex inflorescences. Similar to TMF, rice TAW1 gene were also expressed predominantly in meristems, including the shoot apical meristems (SAM), axillary meristems, primary inflorescence meristems (IM), and branch meristems (BM), to regulate inflorescence architecture through the suppression of meristems phase transition [6]. In petunia, single flower other than multi-flowered inflorescence is produced, so it is very curious to know the functions of PhLSH3a/3b and PhLSH4.

PhLSH5 is a member of the clade IV that contains genes from most species including basal angiosperm, monocots, basal eudicots, and core eudicots. No member has been functionally characterized in this group, however, almost ubiquitous expression pattern of PhLSH5 and wide distribution of its orthologs in plants imply that it might play important and multiple roles in plant vegetative and reproductive development. PhLSH7a and PhLSH7b, two co-orthologs of Arabidopsis AtLSH7/8 genes, show similar tissue-specific expression patterns, predominantly expressed in young fruits, suggesting they may play roles in fruit development. In accordance with this, over-expression of PhLSH7a or PhLSH7b in Arabidopsis has a strong impact on the fertility and fruit development of the transgenic plants. The 35S:PhLSH7a and 35S:PhLSH7b transgenic Arabidopsis plants also show comparable phenotypic changes during vegetative growth such as small round leaves [Fig. 7]. The highly similar expression patterns and protein function of the PhLSH7a/7b gene pair indicate they may have redundant functions. PhLSH10a and PhLSH10b belong to the same group with high homology of protein sequences that contains identical motifs (Fig. 5), but have different expression patterns (Fig. 6), suggesting they may be functionally divergent genes. PhLSH10c gene probably is involved in regulating root development based on its predominant expression in roots [Fig. 6].

Conclusions

In this study, the ALOG family genes (LSHs) were identified from four wild Petunia species and the hybrid petunia line W115 at genome or transcriptome scales. Based on the analysis of gene structure, phylogenetic relationship, expression pattern and function, it is concluded that the ALOG family has complicated evolution history and diverse expression patterns and functions, and petunia PhLSH7a/7b genes have significant functions in plant development, especially in fruit development. This work provides an important foundation for further elucidating the biological function of LSH genes in petunia.

Methods

Plant materials and grow conditions

Petunia hybrida line W115 (MD) and Arabidopsis thaliana (Col-0) were used as the plant materials in this study and the seeds was originally obtained from Department of Molecular Cell Biology, VU-University, The Netherlands (gifts by prof. Ronald Koes). Plant materials were grown in greenhouse under a light condition of 16 h light/8 h dark and a luminous intensity of 170 μmol·m− 2·s− 1, with a humidity of 75% and a temperature of 22–25 °C.

Identification of ALOG genes from petunia species

The protein sequences of Arabidopsis and rice ALOG genes were downloaded from NCBI. The sequence data of P. inflata and P. axillaris were retrieved from Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/) [26]. Two approaches were used to identify ALOG family genes in petunia. First, the ALOG protein sequences identified previously in Arabidopsis and rice were used as queries to search the genome and transcriptome datasets of P. inflata and P. axillaris [26, 27, 33] using the tBLASTx (translated nucleotide to translated nucleotide) program with default parameters. Second, the HMM profile for the DUF640 domain (PF04852) obtained from the Pfam database was used to search the annotated petunia proteomes. The obtained sequences were merged to remove redundancy and examined for the presence of the ALOG domain at the NCBI CD search (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi).

The ALOG genes from P. integrifolia, P. exserta and P. hybrida were recognized by BLAST searching the transcriptome databases at NCBI [27, 34] using the nucleotide sequences of the obtained P. inflata and P. axillaris ALOG genes as queries.

Cloning of ALOG genes from petunia W115

To further confirm the identified genes, full-length genomic DNA sequence and complete CDS of P. hybrida line W115 ALOG genes were amplified using gene-specific primers. Mixture of different tissues was used to extract total RNA with RNA pure Total RNA Kit (Aidlab, China). 2 μg of RNA was used to synthesize the cDNA using cDNA synthesis Kit (Takara, Japan) with Oligo dT Primer and Random 6 mers. Then 2 μl of cDNA dilution (1:20) was added in PCR system with the 2 × High-Fidelity Master Mix DNA Polymerase (Tsingke, China). The products of PCR were purified with Axyprep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen, USA), and then cloned into pMD18-T (Takara, Japan) followed by heat shock into E. coli DH5α. For each gene, three positive clones were picked for sequencing (Augct, China).

Multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis

MEGA 6.0 [35] was used to align the CDS and protein sequences of petunia ALOG genes with the ClustalW program. To figure out the evolutionary scenario of the ALOG gene family in angiosperms, ALOG protein sequences from 9 representative species belonging to different angiosperm clades, including Amborella trichopoda as a basal angiosperm, two monocots (Phalaenopsis aphrodite and Oryza sativa), two basal eudicots (Nelumbo nucifera and Aquilegia coerulea), and four core eudicots (P. hybrida and Solanum lycopersicum from the asterids; Vitis vinifera and Arabidopsis thaliana from the rosids), were used for phylogenetic analysis. Besides the 11 petunia genes cloned in this study (Table 1) and 20 previously identified ALOG genes in Arabidopsis [4] and rice [5], we identified 4 ALOG proteins from A. trichopoda and A. coerulea, respectively, 6 from N. nucifera, 7 from P. aphrodite, 8 from V. vinifera, and 13 from S. lycopersicum based on their genome databases (Additional file 4). Multiple alignments of these protein sequences were performed by the MUSCLE program of MEGA 6.0 [35], and the conserved ALOG domains (about 130 aa) were applied to construct phylogenetic tree using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method with JTT + G model and 1000 replicates of bootstrap. The JTT + G model with the lowest BIC scores is considered the best model in MEGA6 model selection. Phylogenetic tree of the LSH genes from five Petunia species was constructed with the full-length coding sequences using ML method with the GTR + G + I model (the best model) and 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Gene structure and motif analysis

The exon-intron distribution of the PaLSHs, PiLSHs and PhLSHs genes were analyzed using the Gene Structure Display Server 2.0 (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) [36]. The CDD in NCBI was used to identify conserved domains of the PhLSH proteins with default parameters [37]. Motifs of PhLSH proteins were predicted by the MEME 4.12.0 (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) with parameter settings as follows: the minimum motif width = 6, the maximum motif width = 50, and the maximum number of motifs = 20 [38].

Quantitative RT-PCR

Various samples were collected from W115 petunia, including germinating seeds (sow in petri dish for 3 d), cotyledons (sow in petri dish for 7 d), 5-euphylla seedlings; roots, stems, leaves, and axillary buds (collected from flowering plants); bracts, inflorescences, flower buds (0.1 cm, 0.5 cm, and 6 cm), ovaries (without pollination), and young fruits (5 d after pollination). All samples were kept in liquid nitrogen immediately and hold in − 80°C freezer until they were used.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed with the reported method [39]. PhEF1α was used as a reference gene [40]. Three biological replicates were applied to calculate the mean values ± SD (standard deviation) with the 2−ΔΔCT method [41]. The expression of PhLSH1 in Co was used as calibrator. Primer5.0 was used to design the primers with a product size of 150–250 bp. The specificity of all primers was tested by RT-PCR.

Plasmid construction and Arabidopsis transformation

The pMD-18 T vectors containing PhLSH7a or PhLSH7b genes was double digested by BamHI and SalI (Takara, Japan), then the products were ligated into the pCAMBIA2300 vector to obtain 35S:PhLSH7a and 35S:PhLSH7b construction. Both PCR and double enzyme digestion were used to confirm the constructed plasmids that were electrically transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101. Floral dip method was applied for Arabidopsis (Col-0) transformation as previously reported [42].

Phenotype and transgene expression analysis

Both T1 and T2 generation lines were chosen to record morphological characteristics such as the number of rosette leaves and flowering time. Severely sterile lines were artificially pollinated with wild-type pollen to collect seeds. RT-PCR was applied to analyze the expression level of transgenes and endogenous genes in Arabidopsis as previously reported [42]. ANOVA (analysis of variance) was used to analyze the significant differences with Tukey’s post-test (P < 0.05).

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. PaLSH genes in the P. axillaris genome. a Sequence ID related to the database from https://solgenomics.net/organism/Petunia_axillaris/genome (v1.6.2) [26]. b The transcripts correspond to the TSA (Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly) database of P. axillaris in NCBI [27]. ‘/’ indicates no transcript was identified.

Additional file 2. PiLSH genes in the P. inflata genome. a Sequence ID related to the database from https://solgenomics.net/organism/Petunia_axillaris/genome (v1.0.1) [26]. b The transcripts were identified by nucleotide BLAST search of the TSA (Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly) database of P. integrifolia (GBRV) and P. integrifolia Subsp. inflata (GBDS) in the NCBI [33]. ‘/’ indicates no orthologous transcript was identified.

Additional file 3. Primers used in this study for cloning PhLSH CDS, qRT-PCR and transgene line RT-PCR.

Additional file 4. Sequence details in the phylogenetic analysis. A total of 73 protein sequences were included in the phylogenetic analysis: 11 sequences from Petunia hybrida, 10 sequences from Arabidopsis, 10 from rice, 8 from Vitis vinifera, 4 from Amborella trichopoda, 7 from Phalaenopsis aphrodite, 6 from Nelumbo nucifera, 4 from Aquilegia coerulea and 13 from Solanum lycopersicum.

Additional file 5. PeLSH and PintLSH genes in the transcriptome database. These genes were isolated by nucleotide BLAST search of the TSA (Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly) database of P. integrifolia and P. exserta [29]. ‘–’ means no transcripts was found. Partial indicated that the ORF sequences were incomplete.

Additional file 6. Variations in the CDS and amino acids between PhLSHs and their orthologs in P. axillaris, P. inflata, P. integrifolia and P. exserta. ‘/’ means no gene was isolated; ‘-’ means no protein was translated.

Additional file 7. Multiple alignments of 11 PhLSH proteins. The similarity of the N- and C-terminal sequences is very low. Sequences were colored based on 75% consistency. The absolutely conserved residues are shown in light purple.

Additional file 8. Detailed characteristics of the motifs in the PhLSH proteins.

Additional file 9. Heat map demonstrating the expression of PhLSHs in different tissues using averaged log2 relative expression value. The expression range is shown in color based on a scale. Sd, seeds; Co, cotyledons; S, seedlings; R, roots; St, stems; Lv, leaves; Ax, axillary buds; Br, bracts; I, inflorescences; Fb1–3, flower buds (0.1 cm, 0.5 cm, and 6 cm); O, ovaries and F, fruits. PhEF1α was the reference gene for the transcript level.

Additional file 10. Phenotype analysis of the 35S:PhLSH7a and 35S:PhLSH7b transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 32). The letters indicate the result of statistical differences (P < 0.05).

Acknowledgements

We thank all colleagues in our laboratory for helpful discussions and technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- ALOG

Arabidopsis LSH1 and Oryza G1

- CDS

Coding sequence

- LSH

Light-dependent short hypocotyls

- ML

Maximum likelihood

- NLS

Nuclear localization signal

- ORF

Open reading frame

- qPCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcription PCR

- SAM

Shoot apical meristems

- TFs

Transcription factors

- UTR

Untranslated region

Authors’ contributions

FC designed and performed the experiments, carried out the bio-informatics analyses, and drafted the manuscript. QZ participated in guiding and carrying out some experiments. BJL, LW, FL and STZ participated in data analysis and taking care of the plant materials. JQZ participated in directing the study. MZB participated in the design of this project. GFL, as the corresponding author, provided the idea and designed the framework of this study, and modified the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31471914, 31772345) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant no. 2662018PY015). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The genome sequences of P. axillaris and P. inflata used for identifying the LSH genes in current study were located in Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/organism/Petunia_axillaris/genome and https://solgenomics.net/organism/Petunia_inflata/genome, respectively) [26]. The transcriptome databases used to identify LSH genes of P. integrifolia, P. exserta and P. axillaris were available in NCBI under accessions GBRU01000000, GBRT01000000, and GBRV01000000, respectively [27]. The transcriptome databases of P. inflata were available in NCBI under accessions GBDS00000000, GBDR00000000, and GBDQ00000000 [33]. The transcriptome sequences of P. hybrida ‘Mitchell’ was located in Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/) [34]. The sequences information of PhLSHs was uploaded to the NCBI (accession number MK179267- MK179276).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Feng Chen, Email: 755144502@qq.com.

Qin Zhou, Email: 1648516802@qq.com.

Lan Wu, Email: ivylanblue@126.com.

Fei Li, Email: 841820952@qq.com.

Baojun Liu, Email: bjliumail@126.com.

Shuting Zhang, Email: 1156045520@qq.com.

Jiaqi Zhang, Email: jiaqizhang@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Manzhu Bao, Email: mzbao@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Guofeng Liu, Email: gfliu@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12870-019-2127-x.

References

- 1.Jin JP, Tian F, Yang DC, Meng YQ, Kong L, Luo JC, Gao G. PlantTFDB 4.0: toward a central hub for transcription factors and regulatory interactions in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D1040–D1045. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1996;10(21):2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iyer LM, Anantharaman V, Wolf MY, Aravind L. Comparative genomics of transcription factors and chromatin proteins in parasitic protists and other eukaryotes. Int J Parasitol. 2008;38(1):1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao L, Nakazawa M, Takase T, Manabe K, Kobayashi M, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Matsui M. Overexpression of LSH1, a member of an uncharacterised gene family, causes enhanced light regulation of seedling development. Plant J. 2004;37(5):694–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2003.01993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoshida A, Suzaki T, Tanaka W, Hirano HY. The homeotic gene long sterile lemma (G1) specifies sterile lemma identity in the rice spikelet. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(47):20103–20108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907896106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida A, Sasao M, Yasuno N, Takagi K, Daimon Y, Chen RH, Yamazaki R, Tokunaga H, Kitaguchi Y, Sato Y, et al. TAWAWA1, a regulator of rice inflorescence architecture, functions through the suppression of meristem phase transition. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(2):767–772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216151110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeda S, Hanano K, Kariya A, Shimizu S, Zhao L, Matsui M, Tasaka M, Aida M. CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON1 transcription factor activates the expression of LSH4 and LSH3, two members of the ALOG gene family, in shoot organ boundary cells. Plant J. 2011;66(6):1066–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.MacAlister CA, Park SJ, Jiang K, Marcel F, Bendahmane A, Izkovich Y, Eshed Y, Lippman ZB. Synchronization of the flowering transition by the tomato TERMINATING FLOWER gene. Nat Genet. 2012;44(12):1393–1398. doi: 10.1038/ng.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhi WNT, Song S, Wang YQ, Liu J, Yu H. New insights into the regulation of inflorescence architecture. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19(3):158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyer LM, Aravind L. ALOG domains: provenance of plant homeotic and developmental regulators from the DNA-binding domain of a novel class of DIRS1-type retroposons. Biol Direct. 2012;7:39. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-7-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng P, Liu L, Fang J, Zhao J, Yuan S, Li X. The rice TRIANGULAR HULL1 protein acts as a transcriptional repressor in regulating lateral development of spikelet. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):13712. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14146-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eva S, Kevin W, Lucy N, Saleha B, Mahmut TR, Ian C, Peter BE, Jim B. Two TIR:NB:LRR genes are required to specify resistance to Peronospora parasitica isolate Cala2 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2010;38(6):898–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan DW, Zhou Y, Ye SH, Zeng LJ, Zhang XM, He ZH. BEAK-SHAPED GRAIN 1/TRIANGULAR HULL 1, a DUF640 gene, is associated with grain shape, size and weight in rice. Sci China Life Sci. 2013;56(3):275–283. doi: 10.1007/s11427-013-4449-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lei Y, Su S, He L, Hu X, Luo D. A member of the ALOG gene family has a novel role in regulating nodulation in Lotus japonicus. J Integr Plant Biol. 2019;61(4):463–477. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho E, Zambryski PC. ORGAN BOUNDARY1 defines a gene expressed at the junction between the shoot apical meristem and lateral organs. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(5):2154–2159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018542108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hibara K, Takada S, Tasaka M. CUC1 gene activates the expression of SAM-related genes to induce adventitious shoot formation. Plant J. 2003;36(5):687–696. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hibara K, Tasaka M. CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON3; a NAC box gene that regulate organ separation and SAM formation together with CUC1 and CUC2. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003;44:S145. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamiuchi Y, Yamamoto K, Furutani M, Tasaka M, Aida M. The CUC1 and CUC2 genes promote carpel margin meristem formation during Arabidopsis gynoecium development. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:165. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sato DS, Ohmori Y, Nagashima H, Toriba T, Hirano HY. A role for TRIANGULAR HULL1 in fine-tuning spikelet morphogenesis in rice. Genes Genet Syst. 2014;89(2):61–69. doi: 10.1266/ggs.89.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Huang J, Luo NJ, Wei SB, Jin J. Analysing the rice young panicle transcriptome reveals the gene regulatory network controlled by TRIANGULAR HULL1. Rice. 2019;12:6. doi: 10.1186/s12284-019-0265-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren D, Rao Y, Wu L, Xu Q, Li Z, Yu H, Zhang Y, Leng Y, Hu J, Zhu L. The pleiotropic ABNORMAL FLOWER AND DWARF1 affects plant height, floral development and grain yield in rice. J Integr Plant Biol. 2016;58(6):529–539. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu C, Xi WY, Shen LS, Tan CP, Yu H. Regulation of floral patterning by flowering time genes. Dev Cell. 2009;16(5):711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vandenbussche M, Chambrier P, Bento SR, Morel P. Petunia, Your Next Supermodel? Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:72. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Druege U, Franken P. Petunia as model for elucidating adventitious root formation and mycorrhizal symbiosis: at the nexus of physiology, genetics, microbiology and horticulture. Physiol Plant. 2019;165(1):58–72. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerats T, Vandenbussche M. A model system for comparative research: Petunia. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10(5):251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bombarely A, Moser M, Amrad A, Bao M, Bapaume L, Barry CS, Bliek M, Boersma MR, Borghi L, Bruggmann R. Insight into the evolution of the Solanaceae from the parental genomes of Petunia hybrida. Nat Plants. 2016;2(6):16074. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2016.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Y, Wiegertrininger KE, Vallejo VA, Barry CS, Warner RM. Transcriptome-enabled marker discovery and mapping of plastochron-related genes in Petunia spp. BMC Genomics. 2015;16(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-16-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams Justin S., Der Joshua P., dePamphilis Claude W., Kao Teh-hui. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Same 17 S-Locus F-Box Genes in Two Haplotypes of the Self-Incompatibility Locus of Petunia inflata. The Plant Cell. 2014;26(7):2873–2888. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.126920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ning G, Cheng X, Luo P, Liang F, Wang Z, Yu G, Li X, Wang D, Bao M. Hybrid sequencing and map finding (HySeMaFi): optional strategies for extensively deciphering gene splicing and expression in organisms without reference genome. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Villarino Gonzalo H., Bombarely Aureliano, Giovannoni James J., Scanlon Michael J., Mattson Neil S. Transcriptomic Analysis of Petunia hybrida in Response to Salt Stress Using High Throughput RNA Sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e94651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao W, Ye ZQ, Yao XR, He L, Lei YW, Luo D, Su SH. Evolution of ALOG gene family suggests various roles in establishing plant architecture of Torenia fournieri. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Li Na, Wang Yang, Lu Jing, Liu Chuan. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the ALOG Domain Genes in Rice. International Journal of Genomics. 2019;2019:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2019/2146391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nan Wenzhi, Shi Shandang, Jeewani Diddugodage Chamila, Quan Li, Shi Xue, Wang Zhonghua. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of wALOG Family Genes Involved in Branch Meristem Development of Branching Head Wheat. Genes. 2018;9(10):510. doi: 10.3390/genes9100510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong Xiangshu, Lee Jeongyeo, Nou Ill-Sup, Hur Yoonkang. Expression Characteristics of LSH Genes in Brassica Suggest their Applicability for Modification of Leaf Morphology and the Use of their Promoter for Transgenesis. Plant Breeding and Biotechnology. 2014;2(2):126–138. doi: 10.9787/PBB.2014.2.2.126. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu B, Jin J, Guo AY, Zhang H, Luo J, Gao G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2014;31(8):1296. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marchler-Bauer A, Derbyshire MK, Gonzales NR, Lu S, Chitsaz F, Geer LY, Geer RC, He J, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI. CDD: NCBI's conserved domain database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, Ren J, Li WW, Noble WS. MEME Suite: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou Q, Zhang S, Chen F, Liu B, Wu L, Li F, Zhang J, Bao M, Liu G. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the SBP-box gene family in Petunia. BMC Genomics. 2018;19(1):193. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4537-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mallona I, Lischewski S, Weiss J, Hause B, Egea-Cortines M. Validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR during leaf and flower development in Petunia hybrida. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10(1):4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16(6):735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. PaLSH genes in the P. axillaris genome. a Sequence ID related to the database from https://solgenomics.net/organism/Petunia_axillaris/genome (v1.6.2) [26]. b The transcripts correspond to the TSA (Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly) database of P. axillaris in NCBI [27]. ‘/’ indicates no transcript was identified.

Additional file 2. PiLSH genes in the P. inflata genome. a Sequence ID related to the database from https://solgenomics.net/organism/Petunia_axillaris/genome (v1.0.1) [26]. b The transcripts were identified by nucleotide BLAST search of the TSA (Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly) database of P. integrifolia (GBRV) and P. integrifolia Subsp. inflata (GBDS) in the NCBI [33]. ‘/’ indicates no orthologous transcript was identified.

Additional file 3. Primers used in this study for cloning PhLSH CDS, qRT-PCR and transgene line RT-PCR.

Additional file 4. Sequence details in the phylogenetic analysis. A total of 73 protein sequences were included in the phylogenetic analysis: 11 sequences from Petunia hybrida, 10 sequences from Arabidopsis, 10 from rice, 8 from Vitis vinifera, 4 from Amborella trichopoda, 7 from Phalaenopsis aphrodite, 6 from Nelumbo nucifera, 4 from Aquilegia coerulea and 13 from Solanum lycopersicum.

Additional file 5. PeLSH and PintLSH genes in the transcriptome database. These genes were isolated by nucleotide BLAST search of the TSA (Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly) database of P. integrifolia and P. exserta [29]. ‘–’ means no transcripts was found. Partial indicated that the ORF sequences were incomplete.

Additional file 6. Variations in the CDS and amino acids between PhLSHs and their orthologs in P. axillaris, P. inflata, P. integrifolia and P. exserta. ‘/’ means no gene was isolated; ‘-’ means no protein was translated.

Additional file 7. Multiple alignments of 11 PhLSH proteins. The similarity of the N- and C-terminal sequences is very low. Sequences were colored based on 75% consistency. The absolutely conserved residues are shown in light purple.

Additional file 8. Detailed characteristics of the motifs in the PhLSH proteins.

Additional file 9. Heat map demonstrating the expression of PhLSHs in different tissues using averaged log2 relative expression value. The expression range is shown in color based on a scale. Sd, seeds; Co, cotyledons; S, seedlings; R, roots; St, stems; Lv, leaves; Ax, axillary buds; Br, bracts; I, inflorescences; Fb1–3, flower buds (0.1 cm, 0.5 cm, and 6 cm); O, ovaries and F, fruits. PhEF1α was the reference gene for the transcript level.

Additional file 10. Phenotype analysis of the 35S:PhLSH7a and 35S:PhLSH7b transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 32). The letters indicate the result of statistical differences (P < 0.05).

Data Availability Statement

The genome sequences of P. axillaris and P. inflata used for identifying the LSH genes in current study were located in Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/organism/Petunia_axillaris/genome and https://solgenomics.net/organism/Petunia_inflata/genome, respectively) [26]. The transcriptome databases used to identify LSH genes of P. integrifolia, P. exserta and P. axillaris were available in NCBI under accessions GBRU01000000, GBRT01000000, and GBRV01000000, respectively [27]. The transcriptome databases of P. inflata were available in NCBI under accessions GBDS00000000, GBDR00000000, and GBDQ00000000 [33]. The transcriptome sequences of P. hybrida ‘Mitchell’ was located in Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/) [34]. The sequences information of PhLSHs was uploaded to the NCBI (accession number MK179267- MK179276).