Abstract

The world Health Organization defines health as complete well-being in terms of physical, mental and social, and not merely the absence of disease. To attain this, individual should adapt and self-mange the social, physical and emotional challenges of life. Exposure to chronic stress due to urbanization, work stress, nuclear family, pollution, unhealthy food habits, lifestyle, accidental death in the family, and natural calamities are the triggering factors, leading to hormonal imbalance and inflammation in the tissue. The relationship between stress and illness is complex; all chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease and asthma have their root in chronic stress attributed by inflammation. In recent times, yoga therapy has emerged as an important complementary alternative medicine for many human diseases. Yoga therapy has a positive impact on mind and body; it acts by incorporating appropriate breathing techniques and mindfulness to attain conscious direction of our awareness of the present moment by meditation, which helps achieve harmony between the body and mind. Studies have also demonstrated the important regulatory effects of yoga therapy on brain structure and functions. Despite these advances, the cellular and molecular mechanisms by which yoga therapy renders its beneficial effects are inadequately known. A growing body of evidence suggests that yoga therapy has immunomodulatory effects. However, the precise mechanistic basis has not been addressed empirically. In this review, we have attempted to highlight the effect of yoga therapy on immune system functioning with an aim to identify important immunological signatures that index the effect of yoga therapy. Toward this, we have summarized the available scientific evidence showing positive impacts of yoga therapy. Finally, we have emphasized the efficacy of yoga in improving physical and mental well-being. Yoga has been a part of Indian culture and tradition for long; now, the time has come to scientifically validate this and implement this as an alternative treatment method for stress-related chronic disease.

Keywords: Cytokines, immune response, inflammation, yoga

Introduction

The word “stress” was coined by Hans Selye in 1956 who defined it as “nonspecific response of the human body to any demand for change.” Stress worsens human physiology and triggers autonomic activity, which may damage human body at the physical, mental, or emotional level. Stress may be triggered by external (from the environment, psychological, or social situations) or internal (illness and surgery) factors. Stress leads to negative health outcomes in all the stages of life starting from childhood to elderly.

According to the American Psychological Association, mental stress is known to have adverse effects on health, which has negative impact on multiple organs/systems such as immune, cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, and central nervous system (CNS).[1] Stress is rapidly increasing recent times. Stress is reported to be a common contributing factor in 75%–90% of chronic diseases.[2] To lead a healthy life, it has become essential to reduce the negative effects of stress in day-to-day life. Mental stress can be managed in many different ways, for example, by practicing meditation and alternative holistic therapy like music. Yoga is an ancient Indian method to reduce stress, because yoga employs various physical and mental relaxation methods such as asana, breathing exercises, chants, and meditation. It helps in the integration of mind, body, and spirit and thus improves mental and physical health by stress reduction.[3] The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) has recommended yoga as mind–body medicine.[3] In this review, we have discussed about various aspects of stress-related diseases and the effect of yoga in ameliorating stress-induced changes in human body. Stress can effect the morphology and function of the brain.[4]

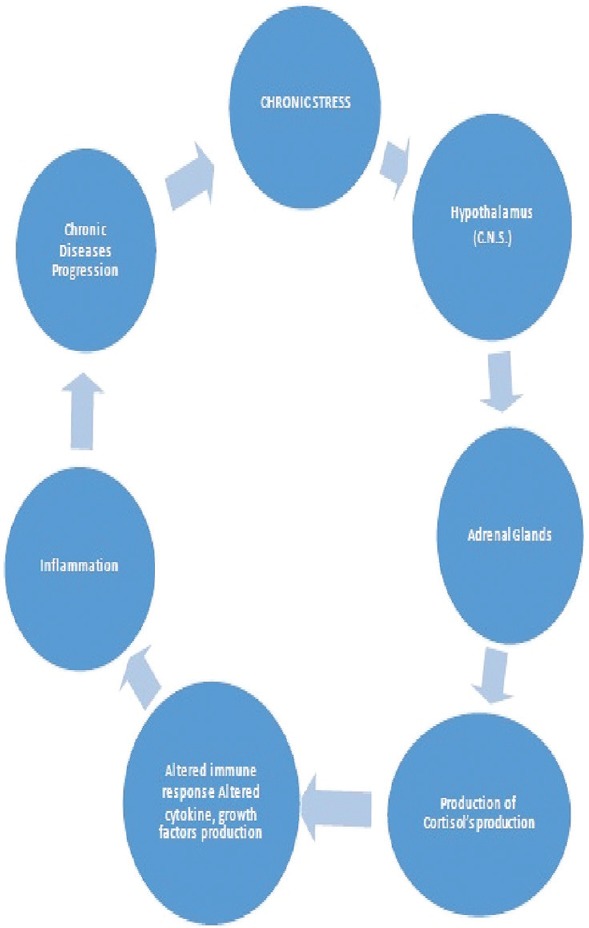

In chronic stress, high level of cortisol increases metabolic rate and decreases synaptic densities in hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (PFC).[5] PFC volume negatively correlates with stress, specifically in white matter of ventrolateral and dorsolateral regions.[5] Anxiety mood disorders, are reported to be aggravated due to stress-induced modifications in the PFC.[6] Stress also impacts the prefrontal gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) pathways impairing the function of limbic structures, which are known to control emotions and behavior.[7] Cortisol released due to stress activates enlarged amygdala.[8] Perceived stress reduction was reported with yoga intervention, and this was also found to decrease basolateral amygdala gray matter density [Figure 1].[9]

Figure 1.

Diagram showing interrelation of chronic stress and inflammation and its effect on endocrine system

Impact of Stress on Human Body

Stress is perceived uncomfortable emotional experience accompanied by predictable biochemical, physiological, and behavioral changes due to disturbance in normal homeostasis.[10] Susceptibility to stress varies from person to person and depends on genetic factors, coping style, type of personality, and social support.[11] Studies have shown that short-term stress provides the driving energy to help the persons to tide over the situations such as examinations or work deadlines. However, chronic stress has a significant impact on immune system, cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, and CNS.[1] Psychological stress alters insulin production leading to diabetes, gastric secretions leading to peptic ulcers, gastric carcinoma, ulcerative colitis, etc.[4]

Immune system closely interacts with CNS while maintaining the physiological homeostasis as well as in regulating cytokine release and mounting inflammatory response against infection.[12] There exists bidirectional communication between CNS and immune system. Neurotransmitters (NTs) as well as immune mediators play important role in CNS-immune system cross talk. NTs released from anoxic terminal of nerve cells reach immune cells by synaptic or nonsynaptic transmission.[13] Nonsynaptically transmitting molecules reach the target cells by diffusion or via the circulating blood. Synaptic NTs are packaged into vesicles, and they are released after reaching the synaptic cleft of target cells; effects of NTs can have stimulatory or inhibitory effects, which depends on activation of receptors, located on postsynaptic cells. In case of stress, NTs activate glial cells, such as astrocytes and microglial cells, resulting in cytokine production.[14] Chronic stress in Alzheimer's disease (AD) leads to increase in amyloid beta (Aβ) assembly and neurofibrillary tangles (NFT). NFT and increased assembly of amyloid beta in the brain can activate immune system and induce the inflammation.[15] Overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines causes imbalance of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory pathways that causes impairment in brain functions. The cytokine imbalance might eventually result in irreversible damage of brain cells, thus contributing to chronic neuropsychological disorders.[13]

Stress hormones such as cortisol and catecholamines are produced by the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical(HPA) axis and sympathetic nervous system (SNS), respectively. The SNS stimulates the adrenal medulla to produce catecholamines (e.g., epinephrine). In parallel, the periventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus produces corticotrophin-releasing factor, which, in turn, stimulates the pituitary to produce adrenocorticotropin. Adrenocorticotropin, in turn, stimulates the adrenal cortex to secrete cortisol-like glucocorticoids (GCs). GCs, catecholamines, cytokines, and other mediators released during stress are thought to be main mediators of stress-induced tissue/organ damage.[2] Cortisol is also known to involve in stress response and immune homeostasis.[16] In acute stress, “fight-or-flight” response of our body responds with hypermobilization of energy to combat stress situations. Chronic state of fight-and-flight response leads to hypervigilance resulting from repeated firing of HPA axis, thus causing dysregulation of normal body system leading to manifestation of stress-related diseases such as diabetes, depression, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases.[17] Increased production of cortisol interferes with homeostatic metabolism of Fats, proteins, and carbohydrates; it increases glucose through gluconeogenesis, causes diabetics, suppresses the immune system, and causes retention of sodium and water by the kidneys, with subsequent increased blood volume and blood pressure.[18] Stress leads to increase in blood cholesterol levels and free fatty acid levels in serum, by stimulating adrenaline and noradrenaline release, causing mobilization of free fatty acids and cholesterol from adipose tissue.[19] The free fatty acid and oxidized cholesterol particles get deposited in the arterial wall and are predisposing factors for cardiac problems and stoke.[20] Chronic stress can also lead to plaque buildup in the arteries, causing atherosclerosis, especially in persons with a high-fat diet and sedentary living.[21] Chronic stress in asthma also leads to the release of histamine, which can trigger severe bronchoconstriction.[22]

Stressful life event has stronger correlation with psychiatric illnesses such as depression and schizophrenia.[23] Stress of all kinds is thought to play a significant role in the development of depression by depleting body's “positive” NTs, such as GABA, serotonin, and dehydroepiandrosterone. In addition, dysfunctional dopaminergic and serotonergic systems are also involved in the development of depression.[23] Deregulated HPA axis is also often reported in those with depressive disorder.[24,25] HPA axis gets hyperactivated in response to abnormal physical or psychological stress, which by disturbing the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems increases cortisol and catecholamines. Increased levels of catecholamines suppress T lymphocytes and thus suppress the immune system and ultimately cause an illness. Chronic stress in pregnant women may cause increased levels of glucocorticoids and proopiomelanocortin during pregnancy and this is shown to effect the embryonic limbic neuronal migration and synaptogenesis in the foetus.[26] Stress induced corticosteroids during pregnancy and postnatal periods, affects postnatal development, by changing the production pattern of cortical limbic receptor and mesocorticolimbic system, leading to risk of dysfunctional maturation in infancy.[27]

Role of Yoga Therapy in Chronic Diseases

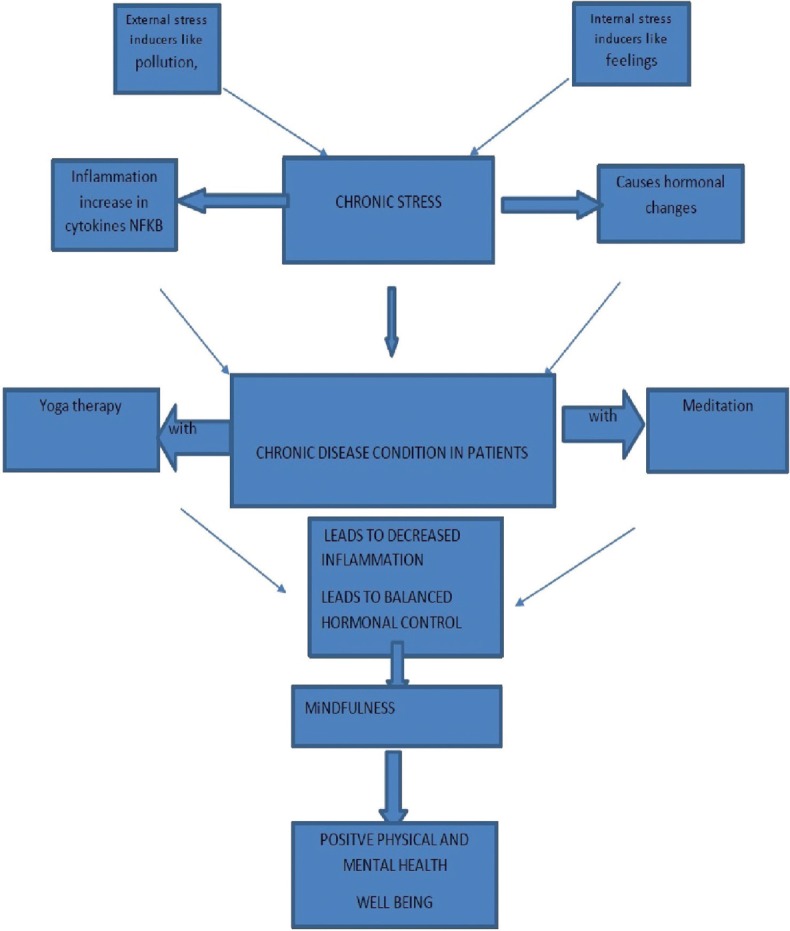

The world Health Organization defines health as complete well-being in terms of physical, mental and social, and not merely the absence of disease. To attain this, individual should adapt and self-mange the social, physical and emotional challenges of life.[28] Yoga therapies are designed to self-manage social, physical, and emotional challenges of life. The concept of yoga was perceived as back as 5000 years ago in the Indian subcontinent [Figure 2]. Yoga is an ancient Indian way of healing, which includes specific techniques such as asana, breathing exercises, chants, and meditation to attain the highest level of consciousness.[19,20] It encourages integration of mind and body to improve mental and physical health by stress reduction.[29] India's proposal of celebrating International Yoga Day on June 21st every year was accepted by 177 member states under the United Nations.[30,31] and in recent reports showed there are 20 million people practicing yoga in U.S. Medical yoga is defined as prevention and treatment of medical conditions by incorporating holistic approach, appropriate breathing techniques, mindfulness, and meditation, in order to achieve harmony between the functions of the body and mind for self-realization. In yoga, it is said that “loss of the connection with self is the main cause that creates disease.”[32] Yoga therapy has shown promising outcomes for the treatment of a myriad number of brain as well as somatic diseases such as depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, schizophrenia, autism, learning disorders obesity, heart diseases, AD, diabetes, depression, gastrointestinal problems, asthma, headaches, hypertension, chronic low back pain, ulcers, and multiple sclerosis.[4,33] However, even-though chronic stress is implicated in many health problems, it is necessary to scientifically validate yoga therapy for reducing stress. This will have significant impact in better understanding and management of chronic disease conditions and their management. Yoga is able to “reverse” harmful molecular reactions involving DNA and significantly alter the modification of histones (H4ac and H3K4me3) by silencing several histone deacetylase genes (HDAC 2, 3, and 9).[34] These changes might lead to modification of inflammatory pathways by decreasing both NF-kB and cytokine level and thus leading to lower levels of inflammation.[35]

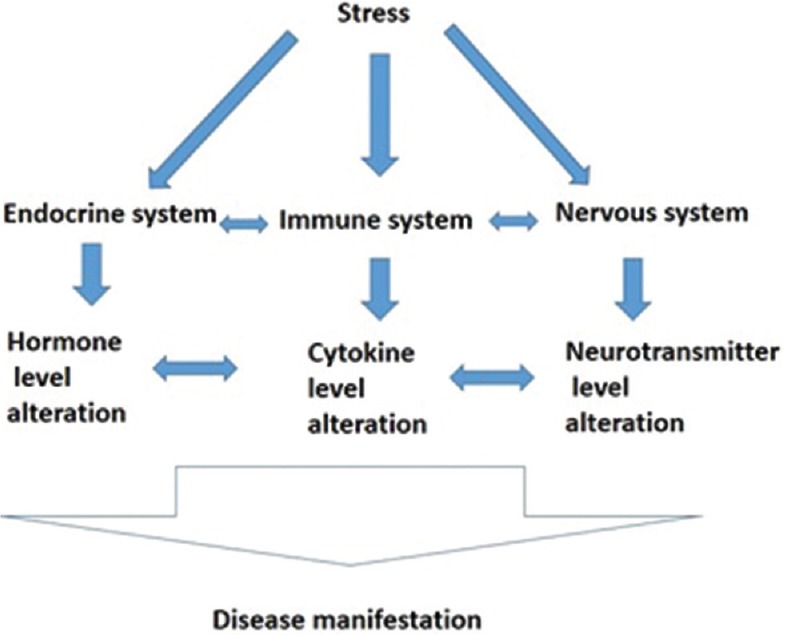

Figure 2.

Diagrammatic representation of impact of stress on human body in disease manifestation

Downregulation of Inflammatory Response in Chronic Disease by Yoga Practice

The positive benefits of yoga therapies are achieved partly by reducing inflammation and improving various immunological parameters of immune response. Stretch exercise for 90 min has shown to increase salivary human β-defensin 2 (HBD-2) levels by HBD-2 expression rate.[36] HBD-2 is an antimicrobial peptide, exerts their effects by destroying the hydrophobic core of lipid bilayers of microbes, and prevents infections. They are expressed in epithelial cells of oral cavity and respiratory tracts and little is realized in emotional stress. The low cytotoxic activity of NK cells eliminates damaged and cancer cells, thereby increasing cancer risk. Kochupillai et al. have investigated the effects of yogic breathing on numbers of NK cells in cancer patients. NK cell numbers increased significantly above the baseline levels after 12 and 24 weeks of the yoga practice.[37] Witek-Janusek et al. have examined the relationship between mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), including yogic breathing practices, and immune function. Their study involving 96 women with breast cancer, who participated in a MBSR program for 8 weeks, showed increased NK cell activity and cytokine levels compared to non-MBSR group, which included low levels of NK cell activity and interferon (IFN)-γ production and high levels of interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-6, and IL-10 production.[38] IFN-γ secreted from NK cells and T cells exerts its pro-inflammatory function by activating endothelial cells and macrophages and by promoting differentiation of T helper 1 (Th1) cells; a decrease in serum IFN-γ levels reduces cellular immunity. Researchers have shown that serum IFN-γ levels increase in patients under examination stress.[15] However, patients who practiced yoga for 12 weeks showed lowered IFN-γ levels than the control group.[39] These findings suggest that practice of yoga could inhibit decline in cellular immunity that is associated with psychological stress. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to modulate the pathologies of various chronic diseases. The activations of transforming growth factor-β, NF-κB, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and IL-6 have been reported in the previous studies on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, obesity, and metabolic syndrome.[40,41] Yadav et al. have reported that yoga reduces markers of oxidative stress and inflammation in 86 patients with chronic inflammatory diseases who participated in a short-term yoga-based lifestyle program for 10 days.[42] The mean level of cortisol decreased and β-endorphins increased from the baseline by day 10 in these patients. The mean reductions in IL-6 and TNF-α levels from the baseline were also observed by day 10. In a study in which breast cancer patients participated in a 12-week yoga program, plasma levels of soluble TNF receptor type II, a marker of TNF activity, remained stable in the yoga group, but increased in the control group.[43] In another study, 12-week Hatha Yoga intervention improved vitality of breast cancer survivors, while reducing the fatigue score and levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-1β 3 months posttreatment. Increasing yoga practice decreases IL-6 and IL-1β production, but not TNF-α production. Therefore, regular yoga exercise might reduce the levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines.[44]

Genome-wide transcriptional profiling identified 282 upregulated genes and 153 downregulated genes after 3 months of yoga in healthy individuals.[35] Yoga increased activity of anti-inflammatory glucocorticoid receptor (GR), which indicates a change in the HPA axis in terms of responding better to cortisol and stopping the stress response more quickly. However, such change in the HPA axis may lead to reduced levels of cortisol; transcription factor NF-κB showed a significant decrease, whereas anti-inflammatory GR and interferon regulatory factors increased and CREB remained the same.[35,43]

Association of yoga practice showed a lower risk by modulating TNF alpha and Aβ metabolism, which showed a greater ratio of proteins Aβ42/Aβ40 in dementia.[45] Study by E S Epelet al (2016), observed significantly more TNF-alpha levels in control group (non meditator) than regular and experienced meditator. They also showed the gene expression changes due to meditation leading to significant silencing of two out of six proinflammatory genes (RIPK2 and COX2) in experienced meditator.[45,46] The extent to which pro-inflammatory genes were silenced was associated with faster cortisol recovery to social stress. On the other hand, the expression of circadian genes was not affected with intensive mindfulness meditation. Unregulated genes were related to energy metabolism, mitochondrial function, insulin secretion, and telomere maintenance in diabetes.[47] Pro-inflammatory genes and pathways get downregulated by yoga therapy are TNF-RII (a marker of TNF activity), IL-1ra, and C-reactive protein (CRP) (inflammatory marker).[35,47,48] Most studies (81%) that measured the activity of inflammation-related genes and/or NF-κB found a significant downregulation. The previous studies have demonstrated positive effect of physical exercise on IL-6 and CRP.[41,43,44,47,48] Physical exercise was found to significantly improve lean muscle mass, BMI, fitness, resting heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and triglycerides to produce benefits in the management of obesity in adolescents.[49] DM and chronic inflammation are strongly related to increased cardiovascular risk. Physical exercise in patients with diabetes improves metabolic profile and exerts anti-inflammatory effects, that is, reduction in IL-6, high-sensitivity CRP (hs-CRP), and TNF-α without weight loss.[50] Increased serum levels of inflammatory mediators have been associated with numerous disorders such as atherosclerosis, Type II diabetes, hypertension, depression, and overall mortality, but intervention of aerobic exercise training can significantly reduce inflammatory mediators.[51] Thus, it can be considered that the yoga interventions would help reduce inflammatory markers and thus contributing to the prevention of various metabolic disorders and future cardiovascular events. Yoga practice has substantial health benefits due to its ability to reduce inflammatory responses.[52] Perceiving this aspect, it has been considered that ancient Indian traditional yoga practice might be helpful in reducing inflammatory markers such as IL-6, TNF-α, and hs-CRP.[35] Yoga practices can be helpful to people of all ages, even to the persons with psychophysiological illness. Shortening of telomere is responsible for aging. Telomere is a part of the chromosomes present at the terminal regions of chromosomes, they are shortened by few nucleotides every time a cell divides, this shortening is implicated in the process that leads to aging. Telomerase is an enzyme that restores partially the lost nucleotide during replications, Yoga practice is shown to increase the expression of two genes related to telomerase (hTR and hTERT), which adds nucleotides at the end of chromosomes that shorten every time a cell divides thus limiting the aging process restriction, and physical activity may lead to decreased blood pressure and help anger management and also increase the expression of telomerase-related genes.[53]

Mechanism of action of yoga is by vagal stimulation by improving baroreflex sensitivity, and reducing inflammatory cytokines, second through parasympathetic activation associated with antistress mechanisms. Yoga reduces perceived stress and HPA axis activation, which improves overall metabolic and psychological profiles.[17] Yogic literature and yogic research amply indicate the utility of yoga practices for achieving a holistic health [Table 1 and Figure 3] and According to Büssing et al.' (2012) article in Social Work Today magazine, efficacy of yoga as a therapeutic alternative for chronic disease was emphasized.[103]

Table 1.

References of elevation of inflammatory markers in disease conditions and reduction after yoga intervention

| Name of the disease | Name of the inflammatory marker | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elevated in disease conditions | Reduced after yoga intervention | ||

| Cardiac disease | NF-κB | Brand et al., 1996[54] | Sarvottam and Yadav 2014[55] |

| IL-6, TNF α, CRP | Vasan et al.[56] | Pullen et al.[57] | |

| Cesari et al.[58] | Shete et al.[59] | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | NF-κB | Miagkov et al.[60] | Arora and Bhattacharjee[61] |

| IL-10 | Crofford et al.[62] | Bower and Irwin[63] | |

| Serum hs-CRP, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10 | Shrivastava et al.[64] | Morgan et al.[65] | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | IL-6 and Stat3 | Grivennikov et al.[66] | Kuo et al.[67] |

| Cancer | NF-kappaB and IL-6-GP130-JAK pathways | Nakagawa and Maeda[68] | Bower et al.[43] |

| Multiple sclerosis | Cytokines IL-1 alpha, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IFN-gamma, TGF beta 1 and 2 and TNF-alpha |

Woodroofe and Cuzner[69] | Gold et al.[70] |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | C-reactive protein, IL-6 | Pradhan et al.[71] | Kohut et al.[51] |

| IL-8, IL-6 (MCP-1) | Longo et al.[72] | Wang et al.[73] | |

| Schizophrenia | IL-1 beta, IL-6, IL-9, and TNF-beta significant increase | Manu et al.[74] | Rao et al.[75] |

| IL-6 in both plasma and CSF | Coughlin et al.[76] | Sanada et al.[77] | |

| Increase in CRP levels | Metcalf et al.[78] | Pascoe et al.[79] | |

| Low back pain | IFN-γ | Cuellar et al.[80] | Cho et al.[81] |

| High levels of hs-CRP | Stürmer et al.[82] | Macphail[83] | |

| Asthma | CRP | Dodig et al.[84] | Pakhale et al.[85] |

| IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, TNF-α, IL-6 | Fatemi et al.[86] | Twal et al.[87] | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | BDNF levels, sTNFR1 | Faria et al.[88] | Abd El-Kader and Al-Jiffri[89] |

| IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α and MCP-1, IFN-γ and IL-1β |

Leung et al.[90] | Vijayaraghava et al.[91] | |

| Depression | IL-6, TNF-α, CRP | Bautista et al.[92] | Kiecolt-Glaser et al.[52] |

| Pruijm et al.[93] | |||

| Chrysohoou et al.[94] | |||

| Blood pressure | IL-6, TNF-α, CRP | Bautista et al.[92] | Von Känel et al.[95] |

| Pruijm et al.[93] | |||

| Chrysohoou et al.[94] | |||

| Ischemic stroke | CRP, IL-6 | Smith et al.[96] | Sarvottam et al.[97] |

| Parkinson’s disease | IL-6 | Chen et al.[98] | Plessy. Biology in Yoga and Shamanism[99] |

| IL-1b, IL-6 and TNF-α | McGeer and McGeer et al.[100] | ||

| Depression | Nuclear factorκB (NFκB) signaling | Koo et al.[101] | David et al.[102] |

IL=Interleukin, NF=Nuclear factor, CRP=C-reactive protein, hs-CRP=High-sensitivity CRP, TNF=Tumor necrosis factor, NF-kappaB=Nuclear factor-kappaB, JAK=Janus kinase, TGF=Transforming growth factor, IFN=Interferon, BDNF=Brain-derived neurotrophic factor, sTNFR=Soluble TNF receptor, MCP-1: Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, CSF=Cerebrospinal fluid

Figure 3.

Yoga in reducing chronic stress

Conclusion and Feature Directions

In this review, we have explored the positive effect of yoga on physical as well as psychological well-being. The most important findings were the immune-dampening effects of yoga in various pathological conditions. Yoga was found to reverse the expression of inflammatory mediators and to maintain homeostasis and physiological functions of various other systems that are related to immune responses. Yoga practices downregulate the expression of a master regulator of inflammation and NF-κB and subsequently influenced the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines in various chronic stress-induced diseases and also maintain balanced endocrine hormones production.

Although the main focus was on the impact of yoga therapy on immune functions in stress-related chronic disease conditions, yoga was also found to have a significant effect on the functions of various other systems such as autonomic, endocrine, HPA axis, as well as psychological aspects that are generally perturbed under stressful conditions.

Finally, we suggest that yoga has the potential to offer clinical benefits to the patients suffering from chronic diseases caused by stressful live events and improve the overall well-being and work performance. Considering the beneficial effects of yoga in various illnesses and given the differences in yoga module recommended by various yoga schools, it has now become essential to standardize and scientifically validate yoga protocol specific to each disease condition. Besides this, studies focusing on a common set of immune markers across all the diseases should be carried out. This will not only help us understand whether the mode of action of yoga is similar across various illnesses but also aid in identifying a common set of blood-based biomarkers indexing effect of yoga.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Anderson NB. Levels of analysis in health science. A framework for integrating sociobehavioral and biomedical research. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:563–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu YZ, Wang YX, Jiang CL. Inflammation: The common pathway of stress-related diseases. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017;11:316. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balaji PA, Varne SR, Ali SS. Physiological effects of yogic practices and transcendental meditation in health and disease. N Am J Med Sci. 2012;4:442–8. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.101980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mishra SK, Singh P, Bunch SJ, Zhang R. The therapeutic value of yoga in neurological disorders. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2012;15:247–54. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.104328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbertson MW, Shenton ME, Ciszewski A, Kasai K, Lasko NB, Orr SP, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:1242–7. doi: 10.1038/nn958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma K, Xu A, Cui S, Sun MR, Xue YC, Wang JH. Impaired GABA synthesis, uptake and release are associated with depression-like behaviors induced by chronic mild stress. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e910. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mizoguchi K, Shoji H, Ikeda R, Tanaka Y, Tabira T. Persistent depressive state after chronic stress in rats is accompanied by HPA axis dysregulation and reduced prefrontal dopaminergic neurotransmission. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;91:170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKlveen JM, Morano RL, Fitzgerald M, Zoubovsky S, Cassella SN, Scheimann JR, et al. Chronic stress increases prefrontal inhibition: A mechanism for stress-induced prefrontal dysfunction. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80:754–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.03.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Evans KC, Hoge EA, Dusek JA, Morgan L, et al. Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2010;5:11–7. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baum A. Stress, intrusive imagery, and chronic distress. Health Psychol. 1990;9:653–75. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.6.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel SD. Stress and health: Psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:607–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ThyagaRajan S, Priyanka HP. Bidirectional communication between the neuroendocrine system and the immune system: Relevance to health and diseases. Ann Neurosci. 2012;19:40–6. doi: 10.5214/ans.0972.7531.180410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian L, Ma L, Kaarela T, Li Z. Neuroimmune crosstalk in the central nervous system and its significance for neurological diseases. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:155. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson CJ, Finch CE, Cohen HJ. Cytokines and cognition – The case for a head-to-toe inflammatory paradigm. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:2041–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynolds A, Laurie C, Mosley RL, Gendelman HE. Oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;82:297–325. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)82016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller DB, O'Callaghan JP. Neuroendocrine aspects of the response to stress. Metabolism. 2002;51:5–10. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.33184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh VP, Khandelwal B, Sherpa NT. Psycho-neuro-endocrine-immune mechanisms of action of yoga in type II diabetes. Anc Sci Life. 2015;35:12–7. doi: 10.4103/0257-7941.165623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKay LI, Cidlowski JA. Physiologic and Pharmacologic Effects of Corticosteroids: Holl-Frei Cancer Medcine. 6th ed. 2003. [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 08]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK13780/

- 19.The Science of Yoga. [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 08]. Available from: https://www.goodreads.com/work/best_book/1360683-the-science-of-yoga-the-yogasutras-of-patanjali-in-sanskrit-with-trans .

- 20.Feuerstein G. The Yoga Tradition : its History, Literature, Philosophy, and Practice. Prescott, Arizona: Hohm Press; 1998. [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 08]. p. 728. Available from: http://archive.org/details/yogatraditionits00feue . [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarafino EP, Smith TW. Health Psychology: Biopsychosocial Interactions. 8th edition. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2014. p. 560. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen E, Miller GE. Stress and inflammation in exacerbations of asthma. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21:993–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salleh MR. Life event, stress and illness. Malays J Med Sci. 2008;15:9–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varghese FP, Brown ES. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in major depressive disorder: A brief primer for primary care physicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:151–5. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v03n0401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McClafferty H. Mind-body medicine in pediatrics. Children (Basel) 2017;4 doi: 10.3390/children4090076. pii: E76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapoor A, Dunn E, Kostaki A, Andrews MH, Matthews SG. Fetal programming of hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal function: Prenatal stress and glucocorticoids. J Physiol. 2006;572:31–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.105254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Painter RC, Roseboom TJ, de Rooij SR. Long-term effects of prenatal stress and glucocorticoid exposure. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2012;96:315–24. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, van der Horst H, Jadad AR, Kromhout D, et al. How should we define health? BMJ. 2011;343:d4163. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alternative Medicine the Definitive Guide. 2nd ed. Pinterest; [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 08]. Available from: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/346777240038237772/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Editors. Yoga Journal Study: 20 Million Americans Practice Yoga. Yoga journal. 2017. [Last accessed 2019 Jun 08]. Available from: https://www.Yogajournal. Com/blog/newstudyfinds20millionyogisus .

- 31.Hoyez AC. The 'world of yoga': The production and reproduction of therapeutic landscapes. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:112–24. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephens I. Medical yoga therapy. Children (Basel) 2017;4 pii: E12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldberg L. Yoga Therapy for Children with Autism and Special. 1st edition. New York, USA: W. W. Norton and Company; 2013. p. 337. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaliman P, Alvarez-López MJ, Cosín-Tomás M, Rosenkranz MA, Lutz A, Davidson RJ. Rapid changes in histone deacetylases and inflammatory gene expression in expert meditators. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;40:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Buric I, Farias M, Jong J, Mee C, Brazil IA. What is the molecular signature of mind-body interventions. A systematic review of gene expression changes induced by meditation and related practices? Front Immunol. 2017;8:670. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eda N, Shimizu K, Suzuki S, Tanabe Y, Lee E, Akama T. Effects of yoga exercise on salivary beta-defensin 2. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:2621–7. doi: 10.1007/s00421-013-2703-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kochupillai V, Kumar P, Singh D, Aggarwal D, Bhardwaj N, Bhutani M, et al. Effect of rhythmic breathing (Sudarshan Kriya and Pranayam) on immune functions and tobacco addiction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1056:242–52. doi: 10.1196/annals.1352.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Witek-Janusek L, Albuquerque K, Chroniak KR, Chroniak C, Durazo-Arvizu R, Mathews HL. Effect of mindfulness based stress reduction on immune function, quality of life and coping in women newly diagnosed with early stage breast cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:969–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gopal A, Mondal S, Gandhi A, Arora S, Bhattacharjee J. Effect of integrated yoga practices on immune responses in examination stress – A preliminary study. Int J Yoga. 2011;4:26–32. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.78178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.López-Hernández FJ, López-Novoa JM. Role of TGF-β in chronic kidney disease: An integration of tubular, glomerular and vascular effects. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:141–54. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Khosravi R, Ka K, Huang T, Khalili S, Nguyen BH, Nicolau B, et al. Tumor necrosis factor- α and interleukin-6: Potential interorgan inflammatory mediators contributing to destructive periodontal disease in obesity or metabolic syndrome. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:728987. doi: 10.1155/2013/728987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yadav RK, Magan D, Mehta N, Sharma R, Mahapatra SC. Efficacy of a short-term yoga-based lifestyle intervention in reducing stress and inflammation: Preliminary results. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18:662–7. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bower JE, Greendale G, Crosswell AD, Garet D, Sternlieb B, Ganz PA, et al. Yoga reduces inflammatory signaling in fatigued breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;43:20–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Bennett JM, Andridge R, Peng J, Shapiro CL, Malarkey WB, et al. Yoga's impact on inflammation, mood, and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1040–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.8860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Epel ES, Puterman E, Lin J, Blackburn EH, Lum PY, Beckmann ND, et al. Meditation and vacation effects have an impact on disease-associated molecular phenotypes. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e880. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanherkar RR, Stair SE, Bhatia-Dey N, Mills PJ, Chopra D, Csoka AB. Epigenetic mechanisms of integrative medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:4365429. doi: 10.1155/2017/4365429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qu S, Olafsrud SM, Meza-Zepeda LA, Saatcioglu F. Rapid gene expression changes in peripheral blood lymphocytes upon practice of a comprehensive yoga program. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shete SU, Verma A, Kulkarni DD, Bhogal RS. Effect of yoga training on inflammatory cytokines and C-reactive protein in employees of small-scale industries. J Educ Health Promot. 2017;6:76. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_65_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wong PC, Chia MY, Tsou IY, Wansaicheong GK, Tan B, Wang JC, et al. Effects of a 12-week exercise training programme on aerobic fitness, body composition, blood lipids and C-reactive protein in adolescents with obesity. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:286–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kadoglou NP, Iliadis F, Angelopoulou N, Perrea D, Ampatzidis G, Liapis CD, et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise training in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14:837–43. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282efaf50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kohut ML, McCann DA, Russell DW, Konopka DN, Cunnick JE, Franke WD, et al. Aerobic exercise, but not flexibility/resistance exercise, reduces serum IL-18, CRP, and IL-6 independent of beta-blockers, BMI, and psychosocial factors in older adults. Brain Behav Immun. 2006;20:201–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Christian L, Preston H, Houts CR, Malarkey WB, Emery CF, et al. Stress, inflammation, and yoga practice. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:113–21. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181cb9377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duraimani S, Schneider RH, Randall OS, Nidich SI, Xu S, Ketete M, et al. Effects of lifestyle modification on telomerase gene expression in hypertensive patients: A pilot trial of stress reduction and health education programs in African Americans. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brand K, Page S, Rogler G, Bartsch A, Brandl R, Knuechel R, et al. Activated transcription factor nuclear factor-kappa B is present in the atherosclerotic lesion. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1715–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI118598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarvottam K, Yadav RK. Obesity-related inflammation &cardiovascular disease: Efficacy of a yoga-based lifestyle intervention. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139:822–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vasan RS, Sullivan LM, Roubenoff R, Dinarello CA, Harris T, Benjamin EJ, et al. Inflammatory markers and risk of heart failure in elderly subjects without prior myocardial infarction: The Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2003;107:1486–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000057810.48709.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pullen PR, Nagamia SH, Mehta PK, Thompson WR, Benardot D, Hammoud R, et al. Effects of yoga on inflammation and exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008;14:407–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cesari M, Penninx BW, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, Nicklas BJ, Sutton-Tyrrell K, et al. Inflammatory markers and onset of cardiovascular events: Results from the health ABC study. Circulation. 2003;108:2317–22. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000097109.90783.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shete SU, Kulkarni DD, Thakur G. Effect of yoga practices on Hs-CRP in Indian railway engine drivers of metropolis. Recent Research in Science and Technology. 2012;4:30–3. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miagkov AV, Kovalenko DV, Brown CE, Didsbury JR, Cogswell JP, Stimpson SA, et al. NF-kappaB activation provides the potential link between inflammation and hyperplasia in the arthritic joint. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13859–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arora S, Bhattacharjee J. Modulation of immune responses in stress by yoga. Int J Yoga. 2008;1:45–55. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.43541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Crofford LJ, Wilder RL, Ristimäki AP, Sano H, Remmers EF, Epps HR, et al. Cyclooxygenase-1 and -2 expression in rheumatoid synovial tissues. Effects of interleukin-1 beta, phorbol ester, and corticosteroids. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1095–101. doi: 10.1172/JCI117060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bower JE, Irwin MR. Mind-body therapies and control of inflammatory biology: A descriptive review. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;51:1–1. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shrivastava AK, Singh HV, Raizada A, Singh SK, Pandey A, Singh N, et al. Inflammatory markers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2015;43:81–7. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morgan N, Irwin MR, Chung M, Wang C. The effects of mind-body therapies on the immune system: Meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grivennikov S, Karin E, Terzic J, Mucida D, Yu GY, Vallabhapurapu S, et al. IL-6 and stat3 are required for survival of intestinal epithelial cells and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:103–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuo B, Bhasin M, Jacquart J, Scult MA, Slipp L, Riklin EI, et al. Genomic and clinical effects associated with a relaxation response mind-body intervention in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakagawa H, Maeda S. Inflammation – And stress-related signaling pathways in hepatocarcinogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4071–81. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i31.4071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Woodroofe MN, Cuzner ML. Cytokine mRNA expression in inflammatory multiple sclerosis lesions: Detection by non-radioactive in situ hybridization. Cytokine. 1993;5:583–8. doi: 10.1016/s1043-4666(05)80008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gold SM, Schulz KH, Hartmann S, Mladek M, Lang UE, Hellweg R, et al. Basal serum levels and reactivity of nerve growth factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor to standardized acute exercise in multiple sclerosis and controls. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;138:99–105. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00121-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, Buring JE, Ridker PM. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2001;286:327–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Longo PL, Artese HP, Rabelo MS, Kawamoto D, Foz AM, Romito GA, et al. Serum levels of inflammatory markers in type 2 diabetes patients with chronic periodontitis. J Appl Oral Sci. 2014;22:103–8. doi: 10.1590/1678-775720130540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang NJ, Li Q, Han B, Pu XQ, Cang Z, Zhu CX, et al. PO377 is serum thyroid-stimulating hormone associated with metabolic syndrome in euthyroid Chinese? Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;106:S238–9. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Manu P, Correll CU, Wampers M, Mitchell AJ, Probst M, Vancampfort D, et al. Markers of inflammation in schizophrenia: Association vs.causation. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:189–92. doi: 10.1002/wps.20117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rao NP, Varambally S, Gangadhar BN. Yoga school of thought and psychiatry: Therapeutic potential. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:S145–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Coughlin JM, Wang Y, Ambinder EB, Ward RE, Minn I, Vranesic M, et al. In vivo markers of inflammatory response in recent-onset schizophrenia: A combined study using [(11) C] DPA-713 PET and analysis of CSF and plasma. Transl Psychiatry. 2016;6:e777. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sanada K, Alda Díez M, Salas Valero M, Pérez-Yus MC, Demarzo MM, Montero-Marín J, et al. Effects of mindfulness-based interventions on biomarkers in healthy and cancer populations: A systematic review. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17:125. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1638-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Metcalf SA, Jones PB, Nordstrom T, Timonen M, Mäki P, Miettunen J, et al. Serum C-reactive protein in adolescence and risk of schizophrenia in adulthood: A prospective birth cohort study. Brain Behav Immun. 2017;59:253–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pascoe MC, Thompson DR, Ski CF. Yoga, mindfulness-based stress reduction and stress-related physiological measures: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;86:152–68. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cuellar JM, Golish SR, Reuter MW, Cuellar VG, Angst MS, Carragee EJ, et al. Cytokine evaluation in individuals with low back pain using discographic lavage. Spine J. 2010;10:212–8. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cho HK, Moon W, Kim J. Effects of yoga on stress and inflammatory factors in patients with chronic low back pain: A non-randomized controlled study. Eur J Integr Med. 2015;7:118–23. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Stürmer T, Raum E, Buchner M, Gebhardt K, Schiltenwolf M, Richter W, et al. Pain and high sensitivity C reactive protein in patients with chronic low back pain and acute sciatic pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:921–5. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.027045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Macphail K. C-reactive protein, chronic low back pain and, diet and lifestyle. Int Musculoskelet Med. 2015;37:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dodig S, Richter D, Zrinski-Topić R. Inflammatory markers in childhood asthma. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;49:587–99. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2011.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pakhale S, Luks V, Burkett A, Turner L. Effect of physical training on airway inflammation in bronchial asthma: A systematic review. BMC Pulm Med. 2013;13:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-13-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fatemi F, Sadroddiny E, Gheibi A, Mohammadi Farsani T, Kardar GA. Biomolecular markers in assessment and treatment of asthma. Respirology. 2014;19:514–23. doi: 10.1111/resp.12284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Twal WO, Wahlquist AE, Balasubramanian S. Yogic breathing when compared to attention control reduces the levels of pro-inflammatory biomarkers in saliva: A pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016;16:294. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1286-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Faria MC, Gonçalves GS, Rocha NP, Moraes EN, Bicalho MA, Gualberto Cintra MT, et al. Increased plasma levels of BDNF and inflammatory markers in Alzheimer's disease. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;53:166–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Abd El-Kader SM, Al-Jiffri OH. Aerobic exercise improves quality of life, psychological well-being and systemic inflammation in subjects with Alzheimer's disease. Afr Health Sci. 2016;16:1045–55. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v16i4.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Leung R, Proitsi P, Simmons A, Lunnon K, Güntert A, Kronenberg D, et al. Inflammatory proteins in plasma are associated with severity of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64971. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vijayaraghava A, Doreswamy V, Narasipur OS, Kunnavil R, Srinivasamurthy N. Effect of yoga practice on levels of inflammatory markers after moderate and strenuous exercise. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:CC08–12. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12851.6021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bautista LE, Vera LM, Arenas IA, Gamarra G. Independent association between inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and TNF-alpha) and essential hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:149–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pruijm M, Vollenweider P, Mooser V, Paccaud F, Preisig M, Waeber G, et al. Inflammatory markers and blood pressure: Sex differences and the effect of fat mass in the CoLaus study. J Hum Hypertens. 2013;27:169–75. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2012.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chrysohoou C, Pitsavos C, Panagiotakos DB, Skoumas J, Stefanadis C. Association between prehypertension status and inflammatory markers related to atherosclerotic disease: The ATTICA study. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:568–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.03.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.von Känel R, Hong S, Pung MA, Mills PJ. Association of blood pressure and fitness with levels of atherosclerotic risk markers pre-exercise and post-exercise. Am J Hypertens. 2007;20:670–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Smith CJ, Emsley HC, Gavin CM, Georgiou RF, Vail A, Barberan EM, et al. Peak plasma interleukin-6 and other peripheral markers of inflammation in the first week of ischaemic stroke correlate with brain infarct volume, stroke severity and long-term outcome. BMC Neurol. 2004;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sarvottam K, Magan D, Yadav RK, Mehta N, Mahapatra SC. Adiponectin, interleukin-6, and cardiovascular disease risk factors are modified by a short-term yoga-based lifestyle intervention in overweight and obese men. J Altern Complement Med. 2013;19:397–402. doi: 10.1089/acm.2012.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen H, O’Reilly EJ, Schwarzschild MA, Ascherio A. Peripheral inflammatory biomarkers and risk of Parkinson's disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:90–5. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Plessy D. Plessy D. Biology in Yoga and Shamanism. [Last accessed on 2019 Jun 08]. Available from: https://www.academia.edu/37784973/Biology_in_Yoga_and_Shamanism .

- 100.McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Inflammation and neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2004;10(Suppl 1):S3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Koo JW, Russo SJ, Ferguson D, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Nuclear factorkappaB is a critical mediator of stressimpaired neurogenesis and depressive behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:266974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910658107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Black DS, Cole SW, Irwin MR, Breen E, St Cyr NM, Nazarian N, et al. Yogic meditation reverses NF-κB and IRF-related transcriptome dynamics in leukocytes of family dementia caregivers in a randomized controlled trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:348–55. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Büssing A, Michalsen A, Khalsa SB, Telles S, Sherman KJ. Effects of yoga on mental and physical health: A short summary of reviews. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:165410. doi: 10.1155/2012/165410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]