Abstract

Background

Given the sudden and unexpected nature of an emergency caesarean section (EmCS) coupled with an increased risk of psychological distress, it is particularly important to understand the psychosocial outcomes for women. The aim of this systematic literature review was to identify, collate and examine the evidence surrounding women’s psychosocial outcomes of EmCS worldwide.

Methods

The electronic databases of EMBASE, PubMed, Scopus, and PsycINFO were searched between November 2017 and March 2018. To ensure articles were reflective of original and recently published research, the search criteria included peer-reviewed research articles published within the last 20 years (1998 to 2018). All study designs were included if they incorporated an examination of women’s psychosocial outcomes after EmCS. Due to inherent heterogeneity of study data, extraction and synthesis of both qualitative and quantitative data pertaining to key psychosocial outcomes were organised into coherent themes and analysis was attempted.

Results

In total 17,189 articles were identified. Of these, 208 full text articles were assessed for eligibility. One hundred forty-nine articles were further excluded, resulting in the inclusion of 66 articles in the current systematic literature review. While meta-analyses were not possible due to the nature of the heterogeneity, key psychosocial outcomes identified that were negatively impacted by EmCS included post-traumatic stress, health-related quality of life, experiences, infant-feeding, satisfaction, and self-esteem. Post-traumatic stress was one of the most commonly examined psychosocial outcomes, with a strong consensus that EmCS contributes to both symptoms and diagnosis.

Conclusions

EmCS was found to negatively impact several psychosocial outcomes for women in particular post-traumatic stress. While investment in technologies and clinical practice to minimise the number of EmCSs is crucial, further investigations are needed to develop effective strategies to prepare and support women who experience this type of birth.

Keywords: Systematic literature review, Childbirth, Emergency caesarean section, Psychosocial outcomes, Maternal health, Postpartum

Introduction

There has been a dramatic increase in caesarean section (CS) rates around the world over the past three decades, particularly in middle and high income countries [1]. At a population level, the World Health Organization has concluded that CS rates higher than 10% are not associated with reductions in maternal and newborn mortality rates [2]. Despite this, recent data has reported rates of 40.5% in Latin America and the Caribbean, 32.3% in Northern America, 31.1% in Oceania, 25% in Europe, 19.2% in Asia and 7.3% in Africa [3]. Globally, CS rates have almost doubled between 2000 and 2015, from 12 to 21% [4].

CSs are broadly classified depending on whether they are an elective or emergency procedure. An elective CS is defined as a planned, non-emergency delivery which occurs before initiation of labour [5]. In contrast, emergency caesarean section (EmCS) is defined as an unplanned CS delivery performed before or after onset of labour, which is typically urgent and is most often required due to fetal, maternal or placental conditions (eg. fetal distress, eclampsia, placental/cord accidents, uterine rupture, failed instrumental birth etc) [5, 6].

While CS has an important place in potentially protecting both mother and baby from harm, it is associated with short and long term physical and psychological risks which can extend many years beyond the current delivery and effect the health of the woman, her child, and future pregnancies [7]. In a review of research on the outcomes of CS, Lobel [8] noted that the procedure is uniquely challenging as it combines surgery and birth, events that elicit very diverse emotional responses. The circumstances surrounding an EmCS add an additional layer of complexity to this experience which has thereby prompted researchers to explore the psychosocial impact of this type of birth. The nature of the event accompanied by a series of subsequent rapid psychological adjustments may be distressing, anxiety-provoking and emotionally unsettling for women [9, 10].

The primary outcome of obstetric care, is of course, to ensure both mother and infant remain physically healthy however, psychosocial aspects and outcomes of maternity care and obstetrics are no less important [11, 12]. Psychosocial outcomes identified and examined in the literature as potentially related to CS include: mental health problems such as, postpartum depression, post-traumatic stress and anxiety; decreased maternal satisfaction with childbirth; the mother infant relationship; parents’ sexual functioning; and health behaviours such as infant feeding.

The current study

Given the nature of EmCS and the increased risk of psychological distress for women, it is imperative to gain insight into the diverse psychosocial outcomes for women experiencing this type of birth. Knowledge and awareness surrounding the impact of EmCS on women’s psychosocial outcomes is likely to enhance the overall quality of maternity care. The aim of the current systematic literature review is to identify, collate, and examine the evidence surrounding women’s psychosocial outcomes of EmCS.

Method

A systematic literature review constituting a rigorous method of research for summarising evidence from multiple studies on a specific topic was undertaken [13, 14]. The present study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) recommendations [15]. An a priori designed study protocol guided the literature search, study selection and data synthesis, with quantitative meta-analysis attempted when possible. This systematic review was registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) database: CRD42018087677.

Search strategy

The search strategy was designed and developed following consultation with a health and medical sciences university librarian in order to ensure a comprehensive search and increase the robustness of the study [16]. The medical and psychological electronic databases of EMBASE, PubMed, Scopus, and PsycINFO were searched between November 2017 and March 2018. When conducting searches, keywords were combined representing the two primary concepts; psychosocial outcomes and EmCS. In this systematic literature review, psychosocial outcomes were considered to be variables that encompass social and psychological aspects of an individual’s life [17]. The Boolean operators ‘OR’ and ‘AND’ were utilised to facilitate maximum inclusion of relevant articles [18]. Detailed search algorithms and indexing language used for each database are outlined in the Additional File 1.

To ensure that included articles were reflective of original and recently published research, limits were applied within the literature search to incorporate inclusion criteria such as: research articles, publication within the last 20 years (1998 to 2018), and peer-reviewed articles [19]. Further, the search was limited to English language publications due to unavailability of funding for language translation. Grey literature or trial registries were not persued for practical purposes.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria (based on the PICOS [population, intervention, comparison, outcome, study design] framework) were established in advance and documented in the review protocol to identify all pertinent studies.

Population: Women who have delivered via EmCS

Intervention: EmCS

Comparison: Any mode of delivery (MoD) where reported, otherwise no comparison

Outcomes: Psychosocial variables (i.e. postnatal depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, infant feeding, sexual functioning, satisfaction, views and experiences)

Study Design: Quantitative (excluding case studies), qualitative or mixed methods

Study selection

Potential papers were screened initially by title and abstract by two reviewers who reviewed half of papers each (MB and NT) and full texts were retrieved for those citations considered potentially relevant for inclusion. Both reviewers completed an initial subset of papers together in order to ensure consistency in their approach. Reference lists of retrieved full text papers were examined to identify potentially relevant studies not captured by electronic searches [20]. Full texts of the remaining articles were independently appraised against the eligibility criteria for final inclusion by two reviewers (MB and NT). In case of disagreement in the selection process, a third reviewer was available for consultation.

Data extraction

Utilising a data extraction form designed by the authors, MB extracted descriptive data on study aims, study design, study location, sample size, data collection period, measures utilised, and included a text description summarising the psychosocial and EmCS related findings from each study. These data were cross-checked by NT. A data synthesis of the findings from each article was then performed, involving identification of prominent and recurrent themes in the literature and the synthesis of findings from studies under thematic headings. This approach has been described as flexible, allowing considerable latitude to systematic reviewers, and provides a means of integrating qualitative and quantitative evidence [20].

Quality assessment

In line with standard systematic literature review methodology a formal methodological quality appraisal of each included study was performed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 11 [21]. This tool allows for the critical appraisal of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies and was developed to address some of the challenges of critical appraisal in systematic mixed studies reviews. The MMAT has been validated and used for quality assessment in similar mixed method systematic reviews [22]. The MMAT comprises 19 items for appraising the methodological quality of 5 different types of studies: qualitative studies (4 items), randomised controlled trials (4 items), non-randomized studies (4 items), quantitative descriptive studies (4 items), and mixed methods studies (4 items). Based on the number of criteria met for an individual study, the overall quality assessment rating (QAR) is presented using descriptors *, **, ***, and ****, ranging from * (single criterion met) to **** (all criteria met). Each study included in the quality assessment was evaluated by two independent reviewers (MB and NT). A third reviewer was available for consultation if disagreement occurred.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

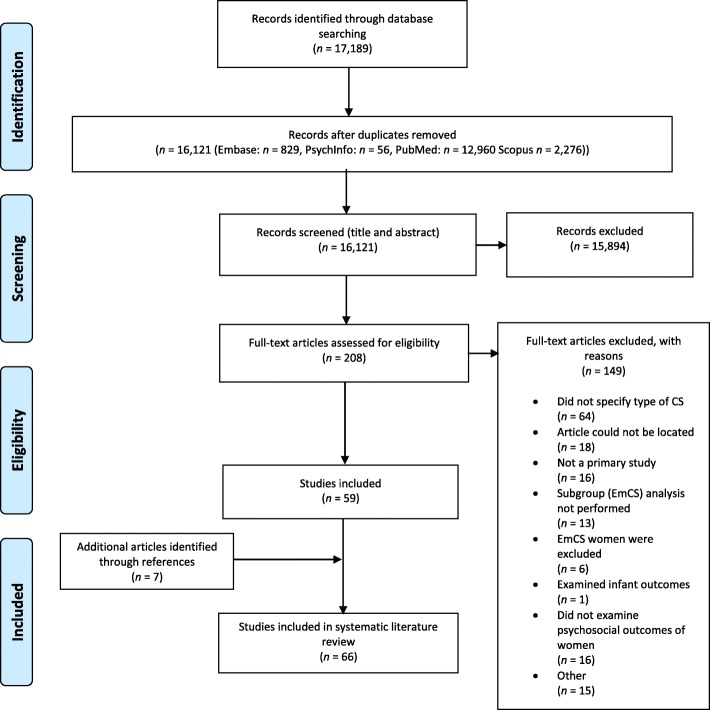

A summary of the search process is illustrated in Fig. 1, as recommended by the PRISMA guidelines [15]. In total 17,189 articles were initially identified. For the initial screening, all search results were imported into citation management software Endnote × 7 where 1068 duplicates were identified and removed, leaving 16,121 articles (Pubmed, n = 12,960, EMBASE n = 829, PsycINFO n = 56, Scopus n = 2276). Titles and abstracts were then assessed by two reviewers (MB, NT), with this process ending with the inclusion of 208 articles. Full texts were then retrieved for those citations considered potentially relevant and assessed for eligibility by the two reviewers (MB, NT). Of these 208 articles, 149 were excluded. The most common reason for exclusion was a lack of differentiation between type of CS when reporting study results (see Fig. 1). Reference lists of included studies were hand searched by the first author and a further 7 articles were subsequently included. A total of 66 relevant articles [5, 9, 23–86] were thus included in the current systematic literature review.

Fig. 1.

Search and Selection Flow Diagram

Description of included studies

Characteristics of the 66 included studies are presented in Table 1. Studies were conducted in 22 different countries with the majority conducted in Sweden (n = 12), followed by the UK (n = 10), and then Nigeria (n = 5). Most studies were quantitative in nature (n = 51), followed by qualitative (n = 14) and just one study with mixed methods. Cross sectional (n = 19) and prospective designs (n = 31) were most prevalent.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of included studies

| Author/Year | Aim | Study Design | Study Location | Participants | Time frame | Study Period | Measure | Psychosocial Outcomes | Relevant Key Findings | MMAT QARa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams, 2012 | To assess the association between mode of delivery (MoD) and maternal postpartum emotional distress. | Prospective Cohort | Norway | 55, 814 | 17 & 30 weeks gestation and 6 months postpartum | 1998–2008 | Short form of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (SCL-8) | Emotional Distress | MoD was not associated with the presence of emotional distress postpartum. | ***** |

| Adewuya, 2006 | To estimate the prevalence PTSD after childbirth and to examine associated factors. | Cross-sectional | Nigeria | 876 | 6 weeks postpartum | 2004 | MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview, Index of marital satisfaction, Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey, Life events scale, Labour agentry scale | PTSD | Instrumental delivery and Emergency Caesarean Section (EmCS) were associated with PTSD, while elective caesarean section (ElCS) sections showed no significant effect. | ***** |

| Ahluwalia, 2012 | To assess the relationship between MoD and breastfeeding. | Prospective longitudinal | United States | 3026 | Before birth and 10 times during the year after birth. | 2005–2006 | Study specific | Breastfeeding | Median breastfeeding duration was 20.6 weeks for EmCS. Breastfeeding duration among women who initiated breastfeeding show that the prevalence of breastfeeding at any time through 60 weeks after delivery was lowest for those who had induced VD or EmCS than among those in the other two groups (spontaneous VD or planned CS). | |

| Beck, 2008 | To explore the impact of birth trauma on mothers’ breast feeding experiences. | Qualitative | New Zealand, US, Australia, UK, Canada | 52 | Unspecified | Unspecified | Study specific | Infant feeding | Women repeatedly explained that their decision to breastfeed was driven by their need to make amends to the infants for the traumatic way they had arrived into the world, for example, by EmCS. | ***** |

| Baas, 2017 | To understand the relationship between client-related factors and the experience of midwifery care during childbirth to improve care. | Prospective longitudinal | Netherlands | 2377 | 20 and 34 weeks pregnant and 6 weeks postpartum | 2009–2011 | Study specific and Labour Agency Scale | Experience of care | MoD effected experiences of care. Women who had an unplanned CS were more likely to indicate that they had received “less than good” midwifery care during childbirth. | **** |

| Baston, 2008 | To examine what factors relate to women’s appraisal of their birth three years later. | Prospective Cohort | England and Netherlands | 2048 | 3 years postpartum | 2003–2004 | Study specific | Satisfaction of experience | EmCS was a factor contributing to a negative appraisal of birth in England and the Netherlands. | **** |

| Bergant, 1998 | To study the subjective psychological and physical stressful experience of childbirth burden. | Cross-sectional | Austria | 1250 | 5 days postpartum | 1993–1994 | EPDS, Trait-Anxiety Inventory, Burden of childbirth | Burden of childbirth | Women who experienced emergency surgical intervention (EmCS and vacuum extraction) demonstrated higher childbirth burden scores. | **** |

| Bryanton, 2008 | To determine factors that predict women’s perceptions of the childbirth experience and to examine whether these vary with the type of birth a woman experiences. | Prospective cohort | Canada | 652 | 12–47 h postpartum | 2004–2005 | Questionnaire Measuring Attitudes About Labour and Delivery | Perceptions of birth | Women who had a planned CS birth scored significantly lower on birth perception than those who had an EmCS or a VD. | **** |

| Burcher, 2016 | To elicit women’s narratives of their unplanned CS births to identify potentially alterable factors that contribute to CS regret. | Qualitative | United States | 14 | 2–6 weeks postpartum | Unspecified | Study specific | Regret and dissatisfaction | Four key themes emerged from patients’ unplanned CS narratives: poor communication, fear of the operating room, distrust of the medical team, and loss of control. | ***** |

| Carquillat, 2016 | To compare subjective childbirth experience according to different delivery methods. | Cross-sectional | Switzerland and France | 291 | 4–6 weeks postpartum | 2014–2015 | Questionnaire for Assessing Childbirth Experience | Childbirth Experience | Women who had an EmCS were at highest risk of experiencing childbirth in a negative way. | **** |

| Chen, 2002 | To compare women who had a VD with those who had a CS in depression, perceived stress, social support, and self-esteem. | Cross-sectional | Taiwan | 357 | 6-weeks postpartum | 1999 | The Beck Depression Inventory, The Perceived Stress Scale, The Interpersonal SupportEvaluation List (ISEL) Short Form, Coopersmith’s Self-Esteem Inventory | Depression, perceived stress, social support, self-esteem | There was no association found in this study between the type of CS (planned or emergency) and psychosocial measures. | ***** |

| Creedy, 2000 | To determine the incidence of acute trauma symptoms and PTSD in women as a result of their labour and birth experiences, and to identify factors that contributed to the women’s psychological distress. | Prospective Longitudinal | Australia | 499 | 4–6 weeks postpartum | 1997–1998 | Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms interview | PTSD | The experience of an EmCS was correlated with the development of trauma symptoms. | **** |

| Durick, 2000 | To examine if unplanned CS would be related to less optimal outcomes and that this relationship would be mediated by mother’s appraisal of the delivery and would attenuate over time. | Longitudinal cohort | United States | 570 | 4 and 12 months postpartum | Unspecified | The Eysenck Personality Inventory Form, The Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, Rosenberg’s (1965) self-esteem scale | Mother-infant interactions, Neuroticism, Depression, Self-esteem, appraisal of the birth experience. | The psychological experiences associated with delivery by unplanned CS, by planned CS, or VD are distinct, and unplanned CS deliveries are appraised most negatively. | **** |

| Eckerdal, 2017 | To explore the association between MoD and postpartum depression. | Longitudinal cohort | Sweeden | 3888 | 118th gestational week, the 32nd week of pregnancy, at 6 weeks, 6months postpartum | 2009–2014 | EPDS | Postpartum depression | A higher prevalence of depressive symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum was noted among women who delivered by EmCS, whereas no significant association with MoD was found regarding PPD at six months postpartum. | ***** |

| Enabudoso, 2011 | To assess the prevalence of satisfaction, and associated factors, among women who had recently delivered by CS. | Cross-sectional | Nigeria | 211 | 2–5 days postpartum | 2010 | Study sepcific | Satisfaction | Satisfaction with CS was significantly higher among women who had ElCS as compared with EmCS. | *** |

| Fenaroli, 2016 | To explore the influence of cognitive and emotional variables on labour and delivery outcomes and examine how individual characteristics, couple adjustment, and medical factors influence the childbirth experience. | Longitudinal cohort | Italy | 121 | Between 32 and 37 weeks of pregnancy and 30–40 days postpartum | 2010–2012 | Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire, EPDS, Dyadic Adjustment Scale | Childbirth expectations, depression | There was no relationship found between MoD and perceived emotional experience. | **** |

| Fenwick, 2009 | To explore women’s experiences of CS. | Qualitative | England | 21 | Between 7 and 32 weeks postpartum | 1999–2000 | Experiences | Feelings of failure were present whether or not the CS was planned or an emergency, and these feelings had an impact on their status passage to motherhood for several reasons. The surgery resulted in the loss of women’s familiar, normal, healthy body. From their perspective, their body had let them down, denying them a normal birth. | ***** | |

| Forti-Buratti, 2017 | To compare the mother-to-infant bond of mothers who gave birth by elective C-section versus EmCS. | Prospective cohort | Spain | 116 | 48–72 h and 10–12 weeks after delivery | Not specified | Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale, responses to separation | Mother-infant bonding | No significant differences between the two CS in bonding, newborn response to separation or type of feeding were observed at any time points. | **** |

| Furuta, 2016 | To identify factors associated with birth-related post-traumatic stress symptoms during the early postnatal period. | Prospective cohort | England | 1824 | 6–8 weeks postpartum | 2010 | Impact of Event Scale | PTSD | EmCS was a high risk factor for post-traumatic stress symptoms. | ***** |

| Gamble, 2005 | To examine the relationship between MoD and symptoms of psychological trauma at 4–6 weeks postpartum | Prospective cohort | Australia | 400 | 72 h and 4–6 weeks postpartum | 2001–2002 | Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview-Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder(MINI-PTSD) | PTSD | Women who had an EmCS or operative VD were more likely to meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD than women who had an ElCS section or spontaneous VD. | **** |

| Gaillard, 2014 | To identify socio-demographic, psychosocial and obstetrical risk factors of postpartum depression. | Prospective cohort | France | 312 | 32–41 weeks gestation, and6–8 weeks postpartum | 2007–2009 | EPDS (French version) | Depression | Women with PND did not differ from the others in MoD (spontaneous vaginal, assisted vaginal, EmCS or ECS). | **** |

| Gibbins, 2001 | To explore, describe and understand the expectations during pregnancy and subsequent experiences of childbirth in women. | Qualitative | England | 8 | 2 weeks post birth | Unspecified | Study specific | Experiences | Women expressed positive feelings about their labours, even though all women felt that labour was different to what they had expected. | ***** |

| Goker, 2012 | To determine the effect of MoD on the risk of postpartum depression. | Cross-sectional | Turkey | 318 | 6 weeks postpartum | Unspecified | EPDS | Depression | Delivering by spontaneous VD, ECS, or EmCS had no effect on EPDS scores. | *** |

| Graham, 1999 | To assess the degree and nature of women’s involvement in the decision to deliver by CS section, and women’s satisfaction with this involvement. | Qualitative | Scotland | 166 | 3–4 days and 6–12 weeks postpartum | 1995–1996 | Study specific | Satisfaction and decision making | Women undergoing ElCS section generally received adequate information; however, with EmCS, half of the women had not received enough information during pregnancy. A significant proportion of women experienced negative feelings, particularly with EmCS (30%). | **** |

| Guittier, 2014 | To determine important elements associated with first delivery experience according to the MoD. | Qualitative | Switzerland | 24 | 4–6 weeks postpartum | 2012 | Study specific | Experiences | The MoD directly impacted on key delivery experience determinants as perceived control, emotions, and the first moments with the newborn. | **** |

| Handelzalts, 2017 | To compare the impacts on childbirth experience of `planned’ delivery (elective CS and vaginal delivery) versus `unplanned’ delivery (vacuum extraction or EmCS). | Cross-sectional | Israel | 469 | Up to 72 h postpartum | 2014–2015 | Subjective Childbirth Experience Questionnaire and Personal Information Questionnaire | Experience | Unexpected MoD (EmCS) results in a more negative birth experience than a planned MoD. | ***** |

| Herishanu-Gilutz, 2009 | To examine the significance of the subjective experience of mothers who gave birth by an EmCS. | Qualitative | Finland | 10 | 4–6 months | Unspecified | Study specific | Experiences | Themes were identified related to the traumatic experience of the operation, e.g. sense of loss of control regarding the decision to operate, feeling of fear and anger toward the caretaking staff. | ***** |

| Hobbs, 2016 | To examine MoD and breastfeeding initiation, duration, and difficulties reported by mothers at 4 months postpartum. | Prospective Cohort | Canada | 3021 | 34–36 weeks gestation and 12–14 months postpartum | 2008 | Unspecified | Infant feeding | Women who delivered by EmCS had a higher proportion of breastfeeding difficulties (41%), and used more resources before (67%) and after (58%) leaving the hospital, when compared to VD (29, 40, and 52%, respectively) or planned CS (33, 49, and 41%, respectively). | **** |

| Iwata, 2015 | To identify factors for predicting post-partum depressive symptoms after childbirth in Japanese women. | Prospective Cohort | Japan | 479 | 1 day before hospital discharge, 1, 2, 4, and 6 months post-partum. | 2012–2013 | EPDS, The Postnatal Accumulated Fatigue Scale, The Postpartum Maternal Confidence Scale, The Childcare Value Scale | Depression | Six variables reliably predicted the risk of postpartum depression including EmCS. | ***** |

| Jansen, 2007 | To investigate fatigue and HRQoL in women after VD, ElCS, and EmCs. | Prospective cohort | Netherlands | 141 | 12–24 h after VD and 24-48 h after CS and 1,3, weeks postpartum | 2003–2004 | The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, EuroQoL 5D, Short-Form 36 | HRQoL | Patients after VD had higher mean physical HRQoL scores than after CS. The average period to reach full physical recovery was 3 weeks after VD, 6 weeks after elective CS, and 6 weeks after EmCS. | ***** |

| Karlström, 2017 | To compare self-reported birth outcomes for women undergoing birth through spontaneous onset of labour between those who actually had a vaginal birth and those who eventually had an EmCS. | Prospective Longitudinal | Sweden | 870 | Mid pregnancy (18–19 weeks), late pregnancy (32–34 weeks), 2 months and 1 year postpartum/ | Unspecified | Study specific | Birth fear and experience | Birth experience were more among women having an EmCS. | **** |

| Karlstrom, 2007 | To investigate women’s experience of postoperative pain and pain relief after CS and factors associated with pain assessment and the birth experience. | Cross-sectional | Sweden | 60 | 2–9 days postpartum | 2004 and 2005 | The Visual Analog Scale, and study specific | Experiences | The risk of a negative birth experience was 80% higher for women undergoing an EmCS compared with elective CS. | *** |

| Loto, 2010 | To examine the association between the MoD, self-esteem, and parenting self-efficacy both at delivery and at 6 weeks postpartum. | Prospective cohort | Nigeria | 115 | Prior to hospital discharge and 6 weeks postpartum | 2007–2008 | Rosenberg self-esteem scale and parent–child relationship questionnaire | Self-esteem | Factors that were significantly associated with low self-esteem include being single and having EmCS. | *** |

| Loto, 2009 | To assess the level of self-esteem of newly delivered mothers who had CS andevaluate the sociodemographic and obstetrics correlates of low self-esteem in them. | Cross-sectional | Nigeria | 109 | 2007–2008 | Rosenberg self-esteem scale | Self-esteem | EmCS closely correlated with low self-esteem in women who had CS. | **** | |

| Lurie, 2013 | To evaluate sexual behaviour longitudinally in the postpartum period by MoD. | Prospective cohort | Israel | 82 | 6, 12, and 24 weeks postpartum | 2010–2011 | Female Sexual Function Index | Sexual Function | Sexual function did not differ significantly by MoD at 6, 12, or 24 weeks postpartum. | **** |

| Maclean, 2000 | To examine women’s distress in response to one of four obstetric procedures: spontaneous VD; induced VD; instrumental VD; or, EmCS. | Cross-sectional | England | 40 | 6 weeks postpartum | 1996–1997 | Impact of Event Scale, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | Experience, wellbeing, distress | Women who gave birth assisted by instrumental delivery reported the childbirth event as distinctly more distressing than the women in the other three obstetric groups (VD; induced VD; EmCS). | **** |

| Modarres, 2012 | To estimate the prevalence of childbirth-related post-traumatic stress symptoms and its obstetric and perinatal risk factors. | Cross-sectional | Iran | 400 | 6–8 weeks after birth | 2009 | Post-traumatic Symptom Scale-Interview | PTSD | EmCS was a significant contributing factor to PTSD after childbirth. | **** |

| Noyman-Veksler, 2015 | To investigate the protective role of sense of coherence (SOC) and perceived social support in the effect of EmCS/ELCS on postnatal psychological symptoms and impairment in mother–infant bonding. | Prospective Longitudinal | Israel | 142 | 6 and 12 weeks postpartum | Unspecified | Post-partum bonding questionnaire, Post-traumatic diagnostic scale, Edinburgh post-natal depression questionnaire, Sense of coherence, Social support questionnaire | Depression, bonding, PTSD, social support | No effect was found of the MoD on bonding with the infant. An EmCS predicted an increase in PTSD symptoms in Time 2, but only among women with low levels of Time-1 social support. | **** |

| O’Reilly, 2014 | To establish a greater understanding of the emotional and cognitive mechanisms associated with CS. | Cross-sectional | France | 201 | At least 6–8 weeks postpartum | 2011–2012 | Labour Agentry Scale, Maternal Self Report Inventory, Unconditional Self-AcceptanceQuestionnaire | Sense of control during the delivery, maternal self-esteem self-acceptance | Sense of control during labour and delivery was significantly higher for women who had a spontaneous VD when compared to those who had undergone an instrumental VD, a planned, or an EmCS. | ***** |

| Patel, 2005 | To assess the association between elective CS section and PD compared with planned VD and whether EmCS or assisted VD is associated with PD compared with spontaneous vaginal delivery. | Prospective cohort | UK | 10,934 | 8 weeks postpartum | 1991–1992 | EPDS | Depression | No increased risk of PD was found between MoD. | ***** |

| Porter, 2007 | To explore the factors that women identified as distressing so as to understand their responses to standard questions on satisfaction. | Mixed methods | Scotland | 1661 | Up to 22 years postpartum | 2002 | Study specific | Distress | Many women had never had an operation before and the fact that their CS was classified as an “emergency” frightened them. | **** |

| Redshaw, 2010 | To gain a better understanding of CS by investigating women’s recent experiences and reflections on their care. | Qualitative | England | 2960 | 3 months postpartum | 2006 | Study specific | Experiences with care | Fear and confrontation with the unexpected were themes identified from women who had an EmCS. | ***** |

| Rowlands, 2012 | To examine the physical and psychological outcomes of women in the first three months after birth, and whether these varied by MoD. | Cross-sectional | England | 5332 | 3 months postpartum | 2010 | Study specific | PTSD and general psychological outcomes | Women having unplanned CS section births were marginally more likely to report PTSD-type symptoms, however, there was no association between PTSD type symptoms and planned CS section births. | **** |

| Ryding, 1998 | To describe women’s thoughts and feelings during the process of a delivery that ended in an EmCS, to ascertain if an EmCS might fulfil the stressor criterion PTSD according to DMS IV. | Qualitative | Sweden | 53 | 2 days after birth | Unspecified | Study specific | PTSD and Experiences | 55% of women experienced intense fear for their own life or that of their baby. 8% felt very badly treated by the staff. Almost all women had adequate knowledge of the reasons for the EmCS. | ***** |

| Ryding, Wijma 1998 | To compare the psychological reactions of women after EmCS, ElC, instrumental VD, and normal VD. | Prospective cohort | Sweden | 326 | 2 days and 1 month postpartum | 1992–1993 | Wijma Delivery Expectancy Experience Questionnaire the Impact of Event Self-Rating ScaleI, 35-item version of the Symptoms Check List | Experiences and trauma | The EmCS group reported the most negative delivery experience at both times, followed by the lVD group. At a few days postpartum the EmCS group experienced more general mental distress than the VD group, but not when compared with the ElCS or the instrumental VD groups. At 1 month postpartum the EmCS group showed more symptoms of post-traumatic stress than the ECS and instrumental VD groups, but not when compared to the VD group. | **** |

| Ryding, 2000 | To investigate the possibility to categorize women’s experiences of EmCS based on the patterns displayed in their narration of the event, and to describe typical features of those categories. | Qualitative | Sweden | 25 | A few days and 1–2 months postpartum. | Unspecified | Study specific | Experiences | The narratives of the 25 women were categorized as follows: Pattern 1 - confidence whatever happens (n 5); Pattern 2 - positive expectations turning into disappointment (n 7); Pattern 3 - fears that come true (n 9); and Pattern 4 - confusion and amnesia (n 4). | * |

| Safarinejad, 2009 | To quantify the relationship between MoD and subsequent incidence of sexual dysfunction and impairment of quality of life (QOL) both in women and their husbands. | Prospective cohort | Iran | 912 | Every month post deliveryup to 12 months. | 2006–2007 | Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), and International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF), | Sexual Function, QoL | Women with VD and EmCS had statistically significant lower Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) scores as compared with planned CS Section women | ***** |

| Saisto, 2001 | To examine the extent to which personality characteristics, depression, fear andanxiety about pregnancy and delivery, and socio-economic background, predict disappointment with delivery and the risk of puerperal depression. | Prospective Longitudinal | Finland | 211 | Once after the 30thweek of pregnancy, and 2–3 months after delivery | Unspecified | Beck’s Depression Inventory, the NEO-PI Scale for neuroticism, a partnership satisfaction scale, a Pregnancy Anxiety Scale, a revised version of a fear-of-childbirth questionnaire | Disappointment with delivery and satisfaction | Strongest predictors of disappointment with delivery were labour pain and EmCS. | ***** |

| Sarah, 2017 | To investigate the relationship between type of delivery and postpartum depression. | Cross-sectional | Iran | Unspecifed | Unspecified | 2013 | Beck depression inventory | Depression | The prevalence of postpartum depression is 33.4%, respectively, of which 13.8% related to EmCS, 7.2% of vaginal deliveries, and 8% of elective CS. | ** |

| Shorten, 2014 | To explore women’s values and expectations during their process of decision making about the next birth. | Qualitative | Australia | 187 | 36–38 weeks pregnant and 6–8 weeks postpartum | Unspecified | Study specific | Decisions after prior CS | Women described long labours ending in CS did not want to go through it again, and especially did not want to repeat the “emergency” scenario. Many described a sense of loss after the previous CS experience and expressed a personal need to remedy this feeling through a better experience in the next birth. “After an emergency CS I felt I had failed, I felt cheated of the childbirth experience I had wanted”. | ***** |

| Soderquist, 2002 | To study whether or not a more stressful delivery was positively related to traumatic stress after childbirth. | Cross-sectional | Sweden | 1550 | Unspecified | 1994–1995 | Traumatic event scale | Traumatic stress | Traumatic stress symptoms and having a PTSD symptom profile were both significantly related to the experience of an EmCS or an instrumental VD. | **** |

| Somera, 2010 | To explore women’s experience of an EmCS birth to gain a better understanding of their thoughts, and feelings throughout the birth process. | Qualitative | Canadian | 9 | 1–5 days after birth and 11–27 days after birth | Not specified | Open-ended questions | Experience | Seven themes were identified describing the women’s experience: (1) It was for the best, (2) I did not have control, (3) Everything was going to be okay, (4) I was so disappointed, (5) I was so scared, (6) I could not believe it and (7) I was excited. | ***** |

| Spaich, 2013 | To investigate the extent to which satisfaction with childbirth depends on the MoD, and evaluated factors determining postpartum satisfaction. | Prospective cohort | Germany | 335 | Unspecified | 2010–2011 | Salmon’s Item List | Experience | There were no women in the subgroup with EmCS who score indicating an overall negative birth experience. The subjective experience of birth was described as ‘good/very good’ in 89% of the women who underwent EmCS. | **** |

| Storksen, 2013 | To assess the relation between fear of childbirth and previous birth experiences. | Prospective cohort | Norway | 1657 | Weeks 17 and 32 pregnant | 2009–2011 | Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire | Fear | EmCS and vacuum extraction were associated with fear of childbirth in subsequent pregnancies. | ***** |

| Tham, 2007 | To examine the associations between new mother’s sense of coherence (SOC) and obstetric and demographic variables a few days postpartum, and post-traumatic stress symptoms 3 months’ postpartum in relation to women who had undergone an emergency CS section. | Prospective cohort | Sweden | 122 | 2 days and 3 month postpartum | Not specified | Sense of Coherence Scale (SOC-13), Impact of Event Scale (IES-15). | PTSD | 25% of the women reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress to a moderate degree (indicating a need for follow-up), and 9% had a high degree of symptoms (indicating possible PTSD). | **** |

| Tham, 2010 | To describe women with and without symptoms of post-traumatic stress following EmCS, and how they perceived the support received in connection with the birth of their child. | Qualitative | Sweden | 84 | 6–7 months postpartum | Not specified | Questions seeking the women’sexperienced social and emotional support from the staffand from their families | Experience and support | The midwives’ action, the content and organisation of care, the women’s emotions, and the role of the family were main categories that seemed to influence the interviewees’ perceptions of support in connection with childbirth. Women with PTSS further mentioned nervous or non-interested midwives, intense fear and feelings of shame during delivery, lack of postnatal follow-up, long-term postpartumfatigue and inadequate help from husbands as influencing factors. Women without symptoms reported involvement in the EmCS decision and a feeling of relief. | **** |

| Trivino-Juarez, 2017 | To conduct a longitudinal study to analyse differences in HRQoL at the sixth week and sixth month postpartum, with mode of birth as the main independent variable. | Prospective Longitudinal | Spain | 547 | 6 weeks and 6 months postpartum | 2013–2014 | EPDS, SF-36 | HRQoL | Women who had vaginal, forceps or vacuum-extraction births at the sixth week postpartum reported better physical functioning than women who had elective or EmCS. At the sixth month postpartum, a significantly higher proportion of women in the forceps group (34%) than in the EmCS group (15%) reported being less satisfied with their sexual relations than before pregnancy. | **** |

| Tully, 2013 | To examine women’s experiences of and explanations for undergoing cesarean delivery. | Qualitative | England | 115 | Not specified | 2006–2009 | Study specific | Experiences | All mothers described labour prior to their unscheduled caesareans as wasted effort. | ***** |

| Ukpong, 2006 | To investigate postpartum emotional distress including depression women who had a CS by comparing them at 6–8 weeks following childbirth with 47 matched controls who had normal vaginal delivery. | Cross-sectional | Nigeria | 94 | 6–8 weeks postpartum | Unspecified | General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-30), Beck Depression inventory | Depression, general health | There was no relationship between the depression scores and being scheduled for either ElCS or EmCS. | **** |

| Vossbeck-Elsebusch, 2014 | To replicate earlier findings regarding the prediction of PTSD levels following childbirth by known prenatal, perinatal and postnatal predictors. | Prospective cohort | Germany | 224 | 1–6 months | Unspecified | Posttraumatic DiagnosticScale (PDS), University of California, Los Angeles Social SupportInventory (UCLA-SSI-d), Peritraumatic DissociativeExperience Questionnaire (PDEQ), PosttraumaticCognitions Inventory (PTCI), Responsesto Intrusions Questionnaire (RIQ), German version of the PerseverativeThinking Questionnaire (PTQ) | PTSD | The mean PDS (Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale) score for women who had an EmCS were significantly higher than the PDS score for women who had a normal VD. | ***** |

| Wijma, 2002 | To examine whether the women’s psychological condition during pregnancy correlates with their psychological well-being after EmCS. | Prospective cohort | Sweden | 1981 | Gestation week 32, a few days, and one month | Unspecified | Wijma Delivery Expectancy/ Experience Questionnaire, Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory, Stress Coping Inventory, Impact of Event Scale, Symptom Checklist | Fear | Surgical complications including EmCs correlated with postpartum fear of childbirth negatively a few days after the operation, but positively one month later. | **** |

| Wiklund, 2009 | To examine changes in personality from late pregnancy to early motherhood in primiparas having vaginal or CS. | Prospective cohort | Sweden | 314 | 37–39 gestational weeks in pregnancy and 9 months after delivery. | 2003–2006 | Karolinska Personality Scales | Personality | Women who had an EmCS scored higher on the subscale measuring Psychasthenia (low degree of mental energy and stress susceptible) 9 months after birth compared to those who had a spontaneous VD. | **** |

| Wiklund, 2007 | To examine the expectations and experiences in women undergoing a CS on maternal request and compare these with women undergoing CS with breech presentation as the indication and women who intended to have VD acting as a control group and to study whether assisted delivery and EmCS in the control group affected the birth experience. | Prospective cohort | Sweden | 496 | Prior to delivery and 3 months postpartum | 2003–2005 | Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire | Experiences | Women planning a VD but experiencing an EmCS or an assisted VD had more negative birth experiences than the other groups. | **** |

| Xie, 2011 | To examine whether or not CS delivery is associated with increased risk of postpartum depression. | Cross-sectional | China | 534 | 2 weeks postpartum | 2007 | Chinese version of the EPDS (EPDS), Social Support Rating Scale, | Depression | PPD rate was higher in the group who had elective CS delivery than inthe group who had EmCS. | **** |

| Yang, 2011 | To examine whether MoD are associated with postnatal depression. | Prospective cohort | Taiwan | 10,535 | Unspecified | 2003–2006 | Data collected from the National Health Insurance Research Database | Depression | Risk of acquiring PPD was lower in mothers with a normal VD or an instrumental VD compared to mothers with an EmCS. The women who elected to have a CS section was higher risk than an EmCS. | **** |

| Zanardo, 2016 | To assess feelings towards newborn infants in mother swho delivered by elective (ElCD) or emergency EmCS. | Cross-sectional | Italy | 573 | Not specified | 2014–2015 | Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale (MIBS) | Mother-infant bonding | EmCS negatively affected mother bonding and opening emotions, and originated inmother feeling sadness and disappointment for the unplanned delivery. | ** |

aMixed Methods Appraisal Tool Quality Assessment Rating

Quality assessment

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool quality assessment ratings (MMAT QARs) are included in Table 1. Among the 51 quantitative non-randomised studies, 14 met all five criteria, 31 met four criteria, 4 met three criteria and 2 met two criteria. Of the 14 qualitative studies, 12 met all five criteria. The one study with mixed methods met four of the five criteria. The main reason several quantitative studies did not meet all criteria was a lack of reporting for the complete set of outcomes (without adequate justification), response rate or follow-up rate.

Data extraction and synthesis

Key psychosocial outcomes were examined in the final 66 studies. Data synthesis was employed to extract and synthesise data pertaining to key psychosocial outcomes from each study into coherent themes. Psychosocial outcomes potentially associated with EmCS included postpartum depression, post-traumatic stress, health related quality of life, mother infant bonding, infant feeding, sexual function, experiences, satisfaction, self-esteem, distress, and fear. Due to an excess of methodological heterogeneity between studies (even for subsets of studies with some common features), a meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate. Table 2 summarizes evidence of associations for identified psychosocial outcomes and EmCS.

Table 2.

Associations of identified psychosocial outcomes and EmCS

| Key psychosocial outcomes | Number of studies | Association between EmCS and psychosocial outcomes | Inconclusive associations between EmCS and psychosocial outcomes | Qualitative summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postpartum depression (PPD) | 12 | + | Studies reported inconsistent findings. The majority of studies reported no significant association (n = 7) between EmCS and PPD whereas the remaining studies reported a relationship between EmCS and increased symptoms of PPD (n = 5). | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) | 11 | + | All studies (n = 11) reported consistent findings that EmCS was a contributing factor to increasing post-traumatic stress symptoms and PTSD after childbirth. | |

| Health related quality of life | 2 | – | Consistent findings were found across studies (n = 2) that women who had an EmCS had poorer physical functioning compared to other MoDs. | |

| Mother infant bonding | 3 | – | Studies reported inconsistent findings. In n = 1 study EmCS appeared to have a negative association with mothers bonding and opening emotions with their baby. In contrast, no significant affect was found in terms of MoD on mother-infant bonding in the remaining studies (n = 2). | |

| Infant feeding | 3 | – | Consistent findings were found across studies in that EmCS impacted negatively in varying ways on infant feeding (n = 3). Women who have an EmCS were more likely to have had an unsuccessful first breastfeeding attempt, were less likely to breastfed their baby within the first 24 h and upon leaving the hospital, and to breastfeed for a shorter duration of time compared to other MoDs. | |

| Sexual function | 3 | +/− | Studies were inconsistent in their findings (n = 3) in terms of satisfaction with sexual relations after birth and sexual function postpartum. | |

| Experiences | 21 | +/− | In terms of quantitative research (n = 9), the majority of studies found that EmCS was more likely to result in a negative birth experience (n = 6), n = 1 study reported MoD had no influence on mother experiences and n = 2 studies reported that EmCS was related to positive experiences in comparison to other MoDs. In terms of the qualitative studies (n = 12) women described a wide variety of emotions as salient aspects to their EmCS experience however, a number of dominating negative experiences were consistent across all studies | |

| Satisfaction | 4 | – | Consistent findings were reported across all studies (n = 4) with women who had an EmCS more likely to appraise their deliveries less favourably than those who delivered via other MoDs. | |

| Self-esteem | 3 | – | Consistent findings were reported across all studies (n = 3). Women who had an EmCS were more likely to report feelings of emotional vulnerability after delivery including feelings of failure, regret, and lower self-esteem. | |

| Distress | 3 | – | Findings were inconsistent in terms of distress after EmCS. No significant association between MoD and distress were reported in a study (n = 1), another study reported other MoD causing more distress than EmCS (n = 1), the final study reported a relationship between EmCS and distress. | |

| Fear | 2 | – | Inconsistent findings were reported. With n = 1 study reporting EmCS was associated with increased fear of childbirth in subsequent pregnancies and n = 1 study reporting a correlation with fear of childbirth a few days after the operation, however this decreased one month later. | |

| Other | ||||

| Childbirth Burden | 1 | + | Women who experienced emergency surgical intervention (i.e EmCS) were more likely to demonstrate higher childbirth burden scores than any other MoD (n = 1). | |

| Feelings of control | 1 | – | Women who had a spontaneous VD reflected having a significantly higher sense of control during their labour and childbirth relative to with an instrumental VD, a planned CS, or an EmCS (n = 1). | |

+ indicates that some (or all) evidence supports a positive association

- indicates that some (or all) evidence supports a negative association

Key outcomes

Postpartum depression

Twelve studies examined depression as an outcome of EmCS [33, 36, 38, 43, 45, 51, 60, 62, 71, 80, 85, 87]. These studies used varying measures, with the majority (n = 8) utilising the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), three using Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI) and one study not specifying the measure used. Studies identified reported mixed findings in terms of postpartum depression (PPD) and the experience of EmCS. The majority of studies found no significant association between having an EmCS and PPD relative to other MoDs [33, 38, 43, 45, 62, 80, 85]. For example, a prospective cohort study (n = 10, 934) from the UK found no significant evidence of increased risk of PPD between different MoDs including EmCS [62]. In contrast, a much smaller prospective cohort study reported EmCS was a predictor of PPD [51]. Additionally, a recent cross-sectional study conducted in Iran [71] reported that the prevalence of PPD was 33.4%, of which the highest proportion consisted of women who had experienced EmCS at 41.3%. Furthermore, a recent large longitudinal study found that compared with spontaneous VD, women who delivered by EmCS had significantly higher odds of PPD 6 weeks after delivery (OR = 1.45) [36]. Additionally, a cohort study (n = 10, 535) reported that the odds of PPD was significantly lower for women who had a normal VD (OR = 0.67) or an instrumental VD (OR = 0.56) compared to women who had EmCS [87]. However, women who had an elective CS had higher odds of PPD than women who had EmCS (OR = 1.48, p = 0.0168) [87]. Heterogeneity in the tools, their use and findings can be seen in Table 3 and makes the comparison of these figures problematic.

Table 3.

Heterogeneity across studies examining depression

| Study | Cut score | Time post partum | Sample size | Participants with depression |

EmCS subgroup | EmCS subgroup with depression | Evidence of association between EmCS and PPD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale | |||||||

| Eckerdal, 2017 | EDPS> 12 | 6 weeks | 3888 | 505 (13%) | 346 | 50 (16.7%) | No |

| Gaillard, 2014 | EDPS> 12 | 6–8 weeks | 264 | 44 (16.7%) | 44 | 6 (13.6%) | No |

| Goker, 2012 | EDPS> 13 | 6 weeks | 318 | 100 (31.4%) | 106 | 37 (34.9%) | No |

| Iwata, 2015 | EDPS> 9 | 6 months | 479 | 21.5% | 60 | 24 (40%) | Yes |

| Patel, 2005 | EDPS> 13 | 8 weeks | 10,934 | N/A | 572 | 56 (9.8%) | No |

| Xie, 2011 | EDPS> 13 | 2 weeks | 534 | 103 (19.3%) | 149 | 24 (16.1%) | Yes: PPD higher in ElCS than EmCS |

| Beck Depression Inventory | |||||||

| Chen, 2002 | BDI 9–10 | 6 weeks | 357 | N/A | N/A | N/A | No |

| Sarah, 2017 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 33.4%, | N/A | 13.8% of 33.4% | No mention |

| Ukpong, 2006 | BDI > 9 significant, 10–18 mild/moderate, 19–29 moderate/severe, 30–63 extreme | 6–8 weeks | 47 | 29.8% | 40 | N/A | No |

Traumatic stress

Eleven included studies examined trauma as an outcome of an EmCS [24, 34, 41, 42, 59, 60, 65, 66, 73, 76, 81]. These studies were conducted across a diverse range of countries including Australia, Nigeria, UK, Iran, Israel, Sweden and Germany. Study designs included, six cross-sectional, four prospective and one qualitative. All studies consistently reported that EmCS was a contributing factor for post-traumatic stress symptoms and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) after childbirth. Several of the studies stated that any unplanned interventions during childbirth including EmCS were predictors of PTSD [42, 88]. For example, a prospective cohort study (n = 1824) identified EmCS as a risk factor for post-traumatic stress symptoms [41]. Findings from a smaller cross-sectional study in Australia reported a greater than expected frequency of PTSD in women who had EmCS, specifically, 73% reporting trauma symptoms 4–6 weeks postpartum [42]. Further, a qualitative research study conducted in Sweden concluded that experiences of women who delivered via EmCS were traumatic enough to fulfil the stressor criterion of PTSD in the DSM IV [66]. This study stated that 55% of women interviewed a few days after an EmCS reported feelings of intense fear of death or injury to themselves or to their baby during the delivery process [66].

Health related quality of life

Two studies specifically examined Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) [52, 78]. One study utilised the Short-Form 36 (SF-36) to measure HRQoL [78] and the other utilised the SF-36 and the EuroQoL 5D [52]. Both studies reported consistent findings that women with an EmCS had poorer physical functioning, relative to other MoDs. A prospective study in the Netherlands reported that the average period to reach full physical recovery was 3 weeks after VD, 6 weeks after elective CS and EmCS [52]. Similarly, a larger more recent study reported that women who had a vaginal, forceps or vacuum-extraction delivery, had better physical functioning at 6 weeks postpartum relative to those with elective CS or EmCS [78]. In a cohort study in Sweden, women who had EmCS scored higher on the subscale measuring Psychasthenia (low degree of mental energy and stress susceptible) 9 months after birth relative to those with spontaneous VD [84].

Mother-infant bonding

Three studies examined the relationship between EmCS and mother-infant bonding [5, 35, 40] with conflicting results. Two studies utilised the Mother-to-Infant Bonding Scale [5, 40] and the third utilised the Parent-Child Early Relational Assessment Tool [35]. A recent, large scale cross-sectional study found EmCS appeared to have a negative association with mothers bonding and opening emotions with their baby. In contrast, a similar sized study reported no significant differences in mother-infant interactions at 4 or 12 months postpartum between MoD [35]. Similarly, a smaller scale cohort study found that type of CS did not appear to significantly affect mother-infant bonding in the first 72 h following delivery or at 12 weeks postpartum [40].

Infant feeding

Three studies examined the relationship between infant feeding and EmCS [25, 26, 50]. Study designs were prospective cohort, cross-sectional, and qualitative. The large scale prospective cohort study reported that women with EmCS were more likely to have an unsuccessful first breastfeeding attempt and were less likely to breastfed their baby within the first 24 h and upon leaving the hospital [50]. Furthermore, the study reported that women with EmCS had more breastfeeding difficulties (41%), and used more hospital resources before and after leaving the hospital (67, 58%), in comparison to those with a VD (29, 40, and 52%, respectively) or a planned CS (33, 49, and 41%, respectively). Additionally, a similar sized cross-sectional study reported that breastfeeding duration varied substantially with MoD [25]. In the same study, median breastfeeding duration was 45.2 weeks among women who had a spontaneous VD, 38.7 weeks among planned CS, 25.8 weeks among induced VD and 21.5 weeks among women with EmCS [25]. In the qualitative study women frequently stated that their decision to breastfeed was driven by their desire to make up for the traumatic way their baby was delivered, including, by EmCS [26]. In this study a women with EmCS stated, “breastfeeding became almost an act of vindication. I had to make up for failing to provide my daughter with a normal birth, so I sure wasn’t going to fail again” [26].

Sexual function

Three studies, conducted in Israel, Iran and Spain, examined the relationship between EmCS and sexual function postpartum [57, 69, 78], with inconsistent findings. A prospective cohort study reported a significantly higher proportion of women at 6 months postpartum being less satisfied with their sexual relations after birth in the forceps group (34%) relative to the EmCS group (15%) [78]. In contrast, a larger prospective cohort study reported that women who had a VD or EmCS had statistically significantly lower Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) scores on average relative to those with a planned CS [69]. These findings were contrary to that of a small scale cohort study that found no significant difference between average sexual function scores and various MoD postpartum [57], potentially due to a lack of power.

Experiences

A large number (n = 21) of identified studies examined women’s experiences with EmCS. A variety of measures were used across studies including: Impact of Event Scale, Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire, and Questionnaire for Assessing Childbirth Experience (QACE). Studies examined varying aspects of women’s experiences of EmCS including women’s overall birth experiences, emotional experiences and experiences with care and staff.

The majority of quantitative research studies found that EmCS was more likely to result in a negative birth experience. For example, a recent large prospective cohort study in Sweden reported that birth experience was more likely to be negative among women with EmCS relative to VD [53]. Similar findings were reported in another recent but smaller cross-sectional study, where unexpected MoD including EmCS resulted in a higher likelihood of negative birth experiences [48] with this finding supported in numerous other studies [32, 54, 83, 89]. Contrary to this finding, two prospective cohort studies reported that MoD had no direct influence on women’s experience of childbirth [38, 74]. Interestingly, in one of these studies no women in the EmCS subgroup attained a score which indicated a negative birth experience; rather 89% of these women described the birth experience as ‘good/very good’ [74]. Furthermore, the majority of women in this study with EmCS also evaluated their feelings of control during labour and the opportunities they had to make informed choices/decisions as ‘good/very good’ [74]. Interestingly, a large prospective study found that women who had a planned CS scored significantly lower in terms of negative birth perception than those who had an EmCS or a VD [30].

Twelve studies utilised a qualitative design to examine women’s experiences of an EmCS [9, 31, 39, 44, 47, 49, 64, 66, 68, 72, 77, 79]. In all of these studies, women described a wide variety of emotions as salient to their EmCS experience however, a number of dominating negative experiences were consistent across all studies including: loss of perceived control and feelings of helplessness [9, 31, 39, 47, 49]; fear (own or/and for baby) [9, 31, 64, 66, 68, 77]; and disappointment [9, 66, 77]. In a study conducted by Shorten [72] one participant reported “after an emergency caesarean I felt I had failed, I felt cheated of the childbirth experience I had wanted”.

Experiences with maternity care and staff

A large prospective cohort study reported that women who had an unplanned CS were more likely to indicate that they had received “less than good” midwifery care during childbirth [90]. It was suggested that as women who have an EmCS often have their care transferred to other care providers during childbirth, it is possible that the discontinuity of care between the providers may influence women’s experiences with staff [90].

Satisfaction

Four studies examined women’s satisfaction after EmCS [28, 37, 46, 70] with all reporting that women with EmCS were more likely to appraise their deliveries less favourably than those with other MoDs. In a large prospective cohort study conducted in both the Netherlands and England, EmCS appeared to be a contributing factor to a negative appraisal of birth [28].

Self esteem

Three studies examined women’s self-esteem and EmCS [32, 55, 56] with all studies reporting consistent findings. A cross sectional study reported that MoD influenced women’s mood at one-month postpartum, with an item reading ‘I am proud of myself’, representing self-esteem, being more likely to have negative results for women with EmCS [32]. In two smaller Nigerian studies, women were more likely to report feelings of emotional vulnerability after delivery including feelings of failure, regret, and lower self-esteem [55, 56].

Distress

Three studies in Norway, Scotland and England examined distress in relation to EmCS [23, 58, 63]. In a very large prospective cohort study (n = 55,814) conducted over a 10 year period, no significant association between MoD and emotional distress postpartum was reported [23]. Further, a small cross-sectional study reported that women who gave birth assisted by instrumental delivery were more likely to report that their birth was distinctly more distressing than women in three other obstetric groups (VD, induced VD, EmCS) [58]. A mixed methods study reported that the fact that a CS was classified as an “emergency” frightened women, resulting in feelings of distress [63].

Fear

Two studies examined fear as an outcome of EmCS [75, 82]. A large prospective cohort study reported that EmCS was associated with increased fear of childbirth in subsequent pregnancies [75]. A similarly designed and sized study found that EmCS correlated with increased postpartum fear of childbirth a few days after the operation, however this decreased 1 month later [82].

Other outcomes

Childbirth burden and feelings of control were examined in two studies. A large cross-sectional study reported that women who experienced emergency surgical intervention (EmCS and vacuum extraction) were more likely to demonstrate higher childbirth burden scores than those with any other MoD [29]. A small cross-sectional study reported that women who had a spontaneous VD had a significantly higher sense of control during their labour and childbirth relative to those with an instrumental VD, a planned CS, or an EmCS [61].

Discussion

Summary of findings

A number of psychosocial outcomes were consistently and negatively reported to be associated by EmCS including post-traumatic stress, HRQoL, infant feeding, experiences, satisfaction and self-esteem. All studies examining post-traumatic stress consistently found that EmCS was a contributing factor for symptoms and PTSD after childbirth. Two studies exploring HRQoL reported consistent findings that women with EmCS had poorer physical functioning relative to other MoDs. Three studies examining infant-feeding reported that women with EmCS were more likely to have an unsuccessful first breastfeeding attempt, less likely to breastfed within the first 24 h and upon leaving the hospital, and to breastfeed for a shorter duration of time in comparison to other MoDs. These results are consistent with those reported by Ahluwalia [25] who noted that women with EmCS often experience; a difficult labour, stress, and delays in mother-infant interactions, each of which may reduce the likelihood or duration of breastfeeding.

Consistent findings were reported for satisfaction in that women with EmCS were more likely to appraise their deliveries less favourably than those with other MoDs. Studies examining self-esteem found women who had an EmCS were more likely to report feelings of emotional vulnerability after delivery including feelings of failure, regret, and lower self-esteem. Twenty one articles examined varying aspects of women’s experiences of EmCS, which constituted the most commonly examined psychosocial outcome among included studies. In both quantitative and qualitative studies it was reported that women with EmCS were often at the highest risk of assessing their childbirth experience in a negative way and described a wide variety of negative emotions including: loss of perceived control and feelings of helplessness, fear (own or/and for baby), and disappointment.

Psychosocial outcomes including depression, mother-infant bonding, sexual function, fear, and distress were also identified and examined within in the literature. However, studies either reported mixed findings or no sufficient evidence of an association between these outcomes and EmCS.

Limitations

We recognise that potentially relevant articles could have been missed, written in languages other than English, or indexed in other databases other than those chosen and therefore may not have been identified. Studies identified in the review were conducted in 22 diverse countries and as such it must be acknowledged that cross-cultural differences are common and can greatly influence women’s psychosocial outcomes of childbirth [91]. Postnatal access to healthcare; procedural differences; quality of available care; levels of social support; religious beliefs; poverty; societal attitudes regarding pregnancy, birth and motherhood; gender roles and attitudes regarding mental health problems are just a few of the known socio-cultural and environmental factors that may influence findings in the identified studies [92].

Of the included articles the strengths and meaningfulness of the findings differ substantially due to variations in study design, sampling procedures, and sample size. It has been previously identified that research examining the psychosocial outcomes of CS have generally suffered from numerous methodological limitations including; reliance on small sample sizes, use of measures of unknown reliability and validity and the lack of a comparison group or varying comparison groups [93]. Several of these limitations were present in the included studies. For example, as noted previously, one of the primary reasons for excluding articles was the failure to specify or differentiate between type of CS for women in a study. Furthermore, there was often no discussion within included studies about reasons and causes for EmCS and it is possible that some causes are more strongly associated with the psychosocial outcomes examined. Studies identified in the review reported on wide varying time frames for postpartum data collection, with collection ranging from hours after birth to years after birth as well ultilising different cut-points on the same measures for diagnosis. The timing of data collection is an important methodological consideration as there is considerable evidence that the impact of a women’s birth experience changes over time [94]. As time passes, the positive affect from one’s baby and satisfaction with being a mother has been shown in some cases to favourably influence a women’s feeling about her labour experience [94].

As a result of the heterogeneous nature of these factors (exemplified in Table 3 for depression), meaningful pooled quantitative measures of study findings were unable to take place, even for subsets of studies. Overall, there appears a paucity of published evidence with consistent measures and adherence to guidelines for reporting (e.g. for cut-scores) which is crucial to rectify in future studies so that (gold standard) systematic literature reviews can meaningfully pool data in a quantitative manner.

Strengths and implications

To our knowledge, this study is the first to systematically review the available literature on women’s psychosocial outcomes of EmCS. The review presents the findings of quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods studies from a vast array of countries and as a result identifies and examines a wide variety of psychosocial outcomes.

The review has highlighted the need for the further development of technologies and clinical practices to reduce the number of unnecessary EmCSs. Critically, it underscores the requirement for evidence based strategies to provide psychosocial support and information about EmCS in the context of routine antenatal and postnatal care. While high-level research currently exists in this area, for example in the form of routine debriefing to prevent psychological trauma after childbirth (103), it fails to show benefit. More broadly, while programs for postnatal psychosocial support have been promoted in many countries to improve maternal knowledge related to parenting, mental health, quality of life, and physical health, it has been concluded in a systematic review that the most effective strategies remain unclear [95].

Conclusion

The review has highlighted the diverse impact that EmCS can have on women. Numerous psychosocial outcomes that are negatively impacted by this MoD were identified including post-traumatic stress, health-related quality of life, experiences, infant-feeding, satisfaction, and self-esteem. In particular, there was strong consensus that EmCS contributes to symptoms and diagnosis of post-traumatic stress. This review has also highlighted the need for further investigation on this topic using robust methodology including the use of consistent, valid and reliable measures with consistent use of guidelines for appropriate cut scores, consistent comparison groups, adequately powered studies and differentiation between types of CS. Overall, enhanced knowledge and understanding in this area will provide an imperative step towards implementing effective strategies to improve women’s health and well-being following EmCS.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank librarian Vikki Langton at the University of Adelaide library who provided support and knowledge in relation to performing the literature search. We would also like to thank all the authors and publishers of the original studies and the women who took part in all original research.

Abbreviations

- BDI

Beck’s Depression Inventory

- CS

Caesarean Section

- EmCS

Emergency Caesarean Section

- EPDS

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

- HRQoL

Health Related Quality of Life

- MMAT

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- MoD

Mode of Delivery

- PPD

Postnatal depression

- PROSPERO

Prospective register of systematic reviews

- PRSIMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- PTSD

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

- QAR

Quality Assessment Rating

- SF-36

Short-Form 36

- VD

Vaginal delivery

Authors’ contributions

MB, DT, AS have made substantial contributions to conception and design of the review. MB and NT conducted the literature search, initial screening of papers, full text assessment, and quality assessment of included studies. MB extracted data and characteristics of included studies. MB wrote initial manuscript and DT, AS, and CW provided intellectual content and extensive review of final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The current study is funded by the NHMRC project grant 1129648. The funding body played no role in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not needed for this systematic literature review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Madeleine Benton, Email: madeleine.benton@adelaide.edu.au.

Amy Salter, Email: amy.salter@adelaide.edu.au.

Nicole Tape, Email: nicole.tape@adelaide.edu.au.

Chris Wilkinson, Email: chris.wilkinson@sa.gov.au.

Deborah Turnbull, Email: deborah.turnbull@adelaide.edu.au.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12884-019-2687-7.

References

- 1.Mazzoni A, Althabe F, Liu NH, Bonotti AM, Gibbons L, Sanchez AJ, et al. Women’s preference for caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Bjog. 2011;118(4):391–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Statement on Caesarean Section Rates. Geneva; 2015.

- 3.Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller A-B, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boerma T, Ronsmans C, Melesse DY, Barros AJD, Barros FC, Juan L, et al. Global epidemiology of use of and disparities in caesarean sections. Lancet. 2018;392(10155):1341–1348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31928-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zanardo V, Soldera G, Volpe F, Giliberti L, Parotto M, Giustardi A, Straface G. Influence of elective and emergency cesarean delivery on mother emotions and bonding. Early Hum Dev. 2016;99:17–20. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.le Riche H, Hall D. Non-elective caesarean section: how long do we take to deliver? J Trop Pediatr. 2005;51(2):78–81. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmh082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Organization WH . WHO statement on caesarean section rates. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lobel MD, R. S. Psychosocial sequelae of cesarean delivery: review and analysis of their causes and implications. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(11):2272–2284. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somera MJ, Feeley N, Ciofani L. Women's experience of an emergency caesarean birth. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(19–20):2824–2831. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roux SL, van Rensburg E. South African mothers' perceptions and experiences of an unplanned caesarean section. J Psychol Afr. 2011;21(3):429–438. doi: 10.1080/14330237.2011.10820477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clement S. Psychological aspects of caesarean section. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;15(1):109–126. doi: 10.1053/beog.2000.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haines HM, Rubertsson C, Pallant JF, Hildingsson I. The influence of women’s fear, attitudes and beliefs of childbirth on mode and experience of birth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(1):55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilver H, Begley C, Berg M. Measuring women's childbirth experiences: a systematic review for identification and analysis of validated instruments. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):203. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1356-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koffel JB. Use of recommended search strategies in systematic reviews and the impact of librarian involvement: a cross-sectional survey of recent authors. PloS one. 2015;10(5):e0125931–e012593e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Long J, Cumming J. Psychosocial predictors. In: Gellman MD, Turner JR, editors. Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. New York: Springer New York; 2013. pp. 1584–1585. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aveyard H. Doing a literature review in health and social care: A practical guide: McGraw-hill education; 2014.

- 19.Timmins F, McCabe C. How to conduct an effective literature search. Nurs Stand. 2005;20(11):41–47. doi: 10.7748/ns.20.11.41.s53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horsley T, Hyde C, Santesso N, Parkes J, Milne R, Stewart R. Teaching critical appraisal skills in healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;11:CD001270. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001270.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, Bartlett G, O’Cathain A, Griffiths F, Boardman F, Gagnon MP, Rousseau MC. A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. Proposal. 2011.

- 22.Boerleider AW, Wiegers TA, Manniën J, Francke AL, Devillé WL. Factors affecting the use of prenatal care by non-western women in industrialized western countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13(1):81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams SSE-G, M., Sandvik ÅR, Eskild A. Mode of delivery and postpartum emotional distress: A cohort study of 55 814 women. BJOG. 2012;119(3):298–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adewuya AO, Ologun YA, Ibigbami OS. Post-traumatic stress disorder after childbirth in Nigerian women: prevalence and risk factors. BJOG. 2006;113(3):284–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]