Abstract

Background

Sulfotransferases (SOTs) (EC 2.8.2.-) play a crucial role in the sulphate conjugation reaction involved in plant growth, vigor, stress resistance and pathogen infection. SOTs in Arabidopsis have been carried out and divided into 8 groups. However, the systematic analysis and functional information of SOT family genes in cotton have rarely been reported.

Results

According to the results of BLASTP and HMMER, we isolated 46, 46, 76 and 77 SOT genes in the genome G. arboreum, G. raimondii, G. barbadense and G. hirsutum, respectively. A total of 170 in 245 SOTs were further classified into four groups based on the orthologous relationships comparing with Arabidopsis, and tandem replication primarily contributed to the expansion of SOT gene family in G. hirsutum. Expression profiles of the GhSOT showed that most genes exhibited a high level of expression in the stem, leaf, and the initial stage of fiber development. The localization analysis indicated that GhSOT67 expressed in cytoplasm and located in stem and leaf tissue. Additionally, the expression of GhSOT67 were induced and the length of stem and leaf hairs were shortened after gene silencing mediated by Agrobacterium, compared with the blank and negative control plants.

Conclusions

Our findings indicated that SOT genes might be associated with fiber development in cotton and provided valuable information for further studies of SOT genes in Gossypium.

Keywords: Sulfotransferases (SOTs), Cotton, Phylogenetic analysis, Expression and regulation, Fiber development

Background

Sulfur is one of the most basic elements in the plant life. Its assimilation in higher plants and the decrease of metabolically important sulfur compounds are key factors in plant growth, vigor and stress resistance [1]. Sulfur plays an important role in the structure, regulation and catalysis of proteins. According to the previous study, sulfation is essential for nodulation factors of rhizobia to signal to plants in bacteria [2]. In mammals, sulfation contributes to the homeostasis and regulation of many endogenous compounds with biological activity [3]. In plants, the sulphate conjugation reaction appears to play an important part in plant growth, development and stress adaptation [4]. Sulfate must be activated by two subsequent activation steps to form adenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (APS) and 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) before being used for biochemical conversion [5].

Sulfotransferases (SOTs) (EC 2.8.2.-) catalyze the transfer of a sulfate group from PAPS to a hydroxyl group of different substrates [6]. The first plant SOT gene was cloned from Flaveria species (Asteraceae), which was related to the sulfation reaction of flavonol [7]. Subsequently, the cDNA encoding sulfotransferase was isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana and its deduced 302 amino acid polypeptide was highly correlated with plant flavonol sulfotransferase [8]. SOTs are widespread among higher plants, animals and eubacteria [1, 9]. Based on previous studies, SOT proteins were involved in the regulation of diverse physiological and biological processes, such as growth, development, adaptation to land, stomatal closure, drought tolerance and pathogen infection [1, 3, 8–18]. SOTs of Flaveria species were well characterized by means of molecular biology and biochemistry and used as a general model of plant SOTs [7]. These SOTs accept different flavonols as sulfate receptors, which may be involved in adaptation to stress or polar auxin transport. When Arabidopsis seedlings were treated with hormones or stress-related compounds, SOT protein expression was significantly induced by salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate. In addition, the accumulation of SOTs was also observed in the leaves or cell suspensions of mature plants after infection with bacterial pathogens [8]. Several other reports revealed that SOTs can directly catalyze thioglucosate, brassinosteroid, jasmonate, flavonoids and salicylic acid, and directly or indirectly participated in defense signaling, development and stress responding [1, 10, 12, 16, 19].

Cotton (Gossypium) is a major industrial crop that provides important natural fibers and edible oil in the world. The genus contains 45 diploid and 5 tetraploid species. Among them, Gossypium hirsutum L. has been cultivated worldwide and currently accounts for the vast majority of the world’s fiber output (> 90%) of the world’s fiber production [20–22]. The cotton fiber is a unique elongated cell, which is helpful to study cell differentiation. Cotton fibers are single-cell trichomes differentiated that has undergone four major developmental stages, including initiation, elongation, secondary cell wall synthesis, and maturity [23]. The development of cotton fibers in elongation and secondary cell wall synthesis determines the length and strength characteristics of the fiber [24]. In addition, fiber development is a complex process involved in many pathways, including various secondary metabolism, hormone, signal transduction and transcriptional regulatory components [25, 26]. For example, one of the flavonoids, naringenin has been verified to be negatively correlated with fiber development [26, 27]. Auxin and brassinosteroid promoted the fiber initiation as well as elongation; gibberellin acid and ethylene played a positive role during the fiber elongation phase [25–29]. On the other hand, cytokinin, abscisic acid played an opposite role [11]. Jasmonic acid participates in various developmental processes. Different concentrations of jasmonic acid play different roles and high concentration of jasmonic acid inhibits fiber initiation [30, 31]. Similarly, jasmonate inhibited cotton development to some extent by inhibiting gibberellin signal [32]. Overaccumulation of jasmonic acid inhibited both lint and fuzz fiber initiation, reduced the fiber length, and lead to a fiberless phenotype in cotton seeds [33].

Considering that SOTs directly catalyze brassinosteroid, jasmonate, flavonoids and salicylic acid, which are related to growth, cotton fiber development and stress adaptation, it is necessary to understand the information of SOT gene family in Gossypium in order to better understand the relationship between sulfation reaction and physiological processes. However, as far as we know, there is no systematic study of the SOT family in Gossypium. In this study, we identified 46, 46, 76 and 77 SOT genes from G. arboreum, G. raimondii, G. barbadense, and G. hirsutum, respectively, and then looked into the features such as chromosomal locations, phylogenetic evolutionary relationships, gene structures, conserved motifs, tissue and subcellular localization, as well as expression patterns. Our study provided a comprehensive analysis of the Gossypium SOT gene family and the results might be useful in understanding the role of SOT in plant development.

Results

Identification, characterization and chromosomal distribution of SOT genes in four cotton species

According to the results of BLASTP and HMMER 3.1, a total of 245 SOT genes were identified from four cotton species, including 46 genes of G. arboreum, 46 genes of G. raimondii, 76 genes of G. barbadense and 77 genes of G. hirsutum. Protein sequence analysis indicated that all SOT gene proteins encoded a wide range of amino acids ranging from 60 to 672, with an average molecular weights (Mw) at 32.48 kDa and isoelectric points (pI) at 6.58. Subcellular localization analysis showed that 70.6% of 245 SOT genes were localized in the cytoplasm, which may be consistent with their functions as transferases. The SOT gene names, locus IDs and other characteristics were listed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

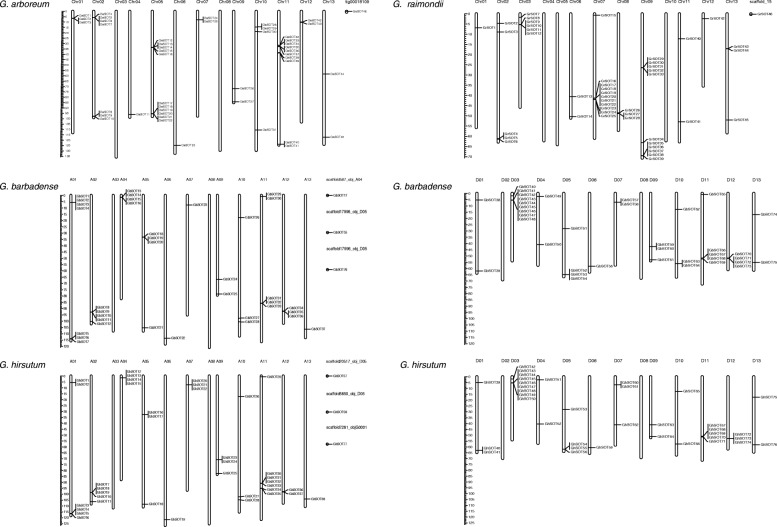

245 SOT genes distributed unevenly on the chromosomes in four cotton species (Fig. 1). Chr09 of G. raimondii contained the largest number of SOT genes (11). By contrast, Chr03/ Chr08 of G. arboreum, Chr04/ Chr05/ Chr10 of G. raimondii, A03/ A08/ D02/ D08 of G. barbadense and A03/ A08/ D02/ D08 of G. hirsutum contained none of SOT genes. In addition, the distribution of SOT genes in G. barbadense and G. hirsutum showed some similarities. So, we further analyzed the collinearity of the SOT gene across these four genomes.

Fig. 1.

Chromosome distribution of SOT genes of four cotton species. The cotton species name was on the left of graphic and chromosome name was at the top of each bar. The vertical scale on the left showed the size of chromosomes and black lines indicated the corresponding position of genes. The scale of the chromosomes was millions of base pairs (Mb). The gene names was correspond to those in Additional file 1: Table S1

Collinearity and duplication analysis of SOT genes

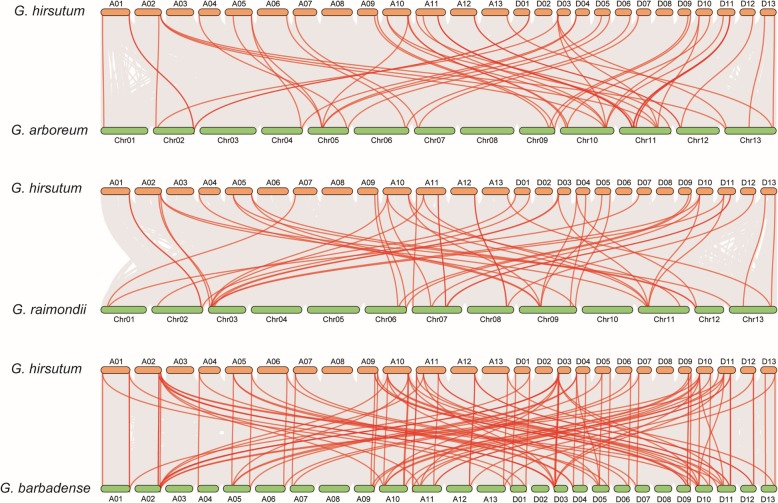

We found out all the homologous genes among these four cotton genomes to analyze the collinearity relationships of SOT genes (Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Table S2). Among all the 77 SOT genes of G. hirsutum, 39 GhSOTs had intergenomic homologous genes in G. arboretum, 37 homologous genes in G. raimondii and 49 homologous genes in G. barbadense, respectively. In total, we identified 32 pairs of common homologous SOT genes in the four cotton species.

Fig. 2.

Collinearity analyses of SOT genes among G. hirsutum, G. barbadense, G. arboretum and G. raimondii. From top to bottom, three graphics displayed the collinear relationship between G. hirsutum and G. arboretum, G. hirsutum and G. raimondii, G. hirsutum and G. barbadense, respectively. Grey lines in the background showed the collinear relationship across the whole genome, while the red lines predominantly displayed the collinear SOT gene pairs

Previous studies in Gossypium showed that gene families always expanded through tandem, whole-genome and segmental duplications [34, 35]. In G. hirsutum, 20 pairs of tandem duplication gene pairs (32 genes) distributing on 12 chromosomes were found (Fig. 3a and Additional file 1: Table S3). In addition, 16 gene pairs of replications were categorized as WGD/segmental duplicates. The remaining gene replication mechanisms were detected as proximal or dispersed. As a result, tandem replication might primarily contribute to the expansion of the SOT gene family during the evolution of G. hirsutum. In order to understand the collinearity of the SOT gene family between G. hirsutum and two diploid cottons ancestors, we also identified these linked gene pairs (Fig. 3b). 56 collinear gene pairs were identified between G. hirsutum and G. arboretum, and 29 of them belonged to At subgroup in G. hirsutum. 48 collinear gene pairs were also found between G. hirsutum and G. raimondii, and 22 genes were Dt subgroup in G. hirsutum.

Fig. 3.

Duplication and synteny of SOT genes among G. hirsutum, G. arboretum and G. raimondii. a Localization and duplication of SOT genes on G. hirsutum chromosomes. Tandem duplication gene pairs were marked with red curve lines. b The synteny of SOT genes between G. hirsutum and two diploid cottons, G. arboretum and G. raimondii. Red lines connected the homologous genes between G. hirsutum and G. arboretum, blue lines connected the homologous genes between G. hirsutum and G. raimondii, respectively

Phylogenetic analysis of SOT genes

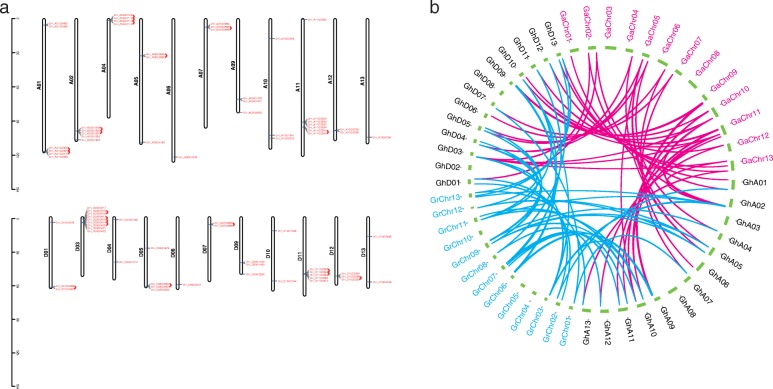

From the phylogenetic tree constructed by all members of the SOT genes (Fig. 4), 170 of the 245 SOT genes were distributed in 4 subfamilies, and the remaining 75 were separated into two clades. The subfamilies VII and VI were the largest two subfamilies, containing 78 and 75 members, respectively. Subfamily V was the smallest one, including only five genes. The SOT genes from four cotton species were more closely related than the genes from Arabidopsis. In addition, at the end of the branch, there were many clades where three genes were clustered together. Generally speaking, of the three genes, two genes are from the At subgroup of tetraploids, one from G. arboretum; or two genes from the tetraploid Dt subgroup, one gene from G. raimondii. This was consistent with the fact that tetraploids came from two diploids [36]. However, after the formation of tetraploids, the relationship between the two tetraploids was closer than that between their ancestors.

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic tree of 266 SOT genes from Gossypium and Arabidopsis. Neighbor-Joining tree was constructed by Mega X program with the full-length amino acid sequence of the SOT genes. The number of subfamily was marked according to the classification results of genes in Arabidopsis. Genes marked in red came from Arabidopsis. Genes marked in purple indicated that the clustered genes came from two tetraploids and one diploid

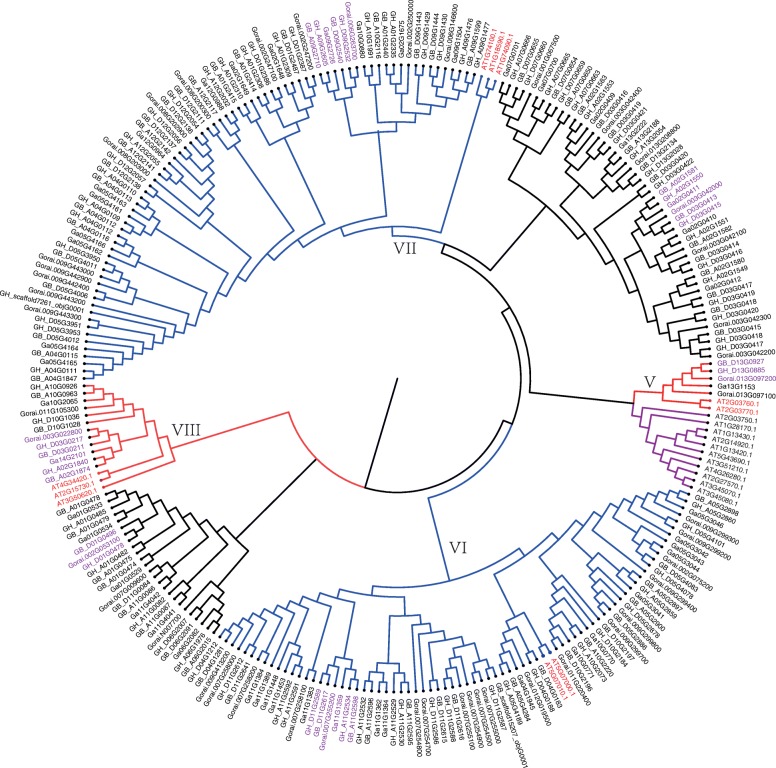

Structural characterizations and conserved motif analyses of GhSOT genes

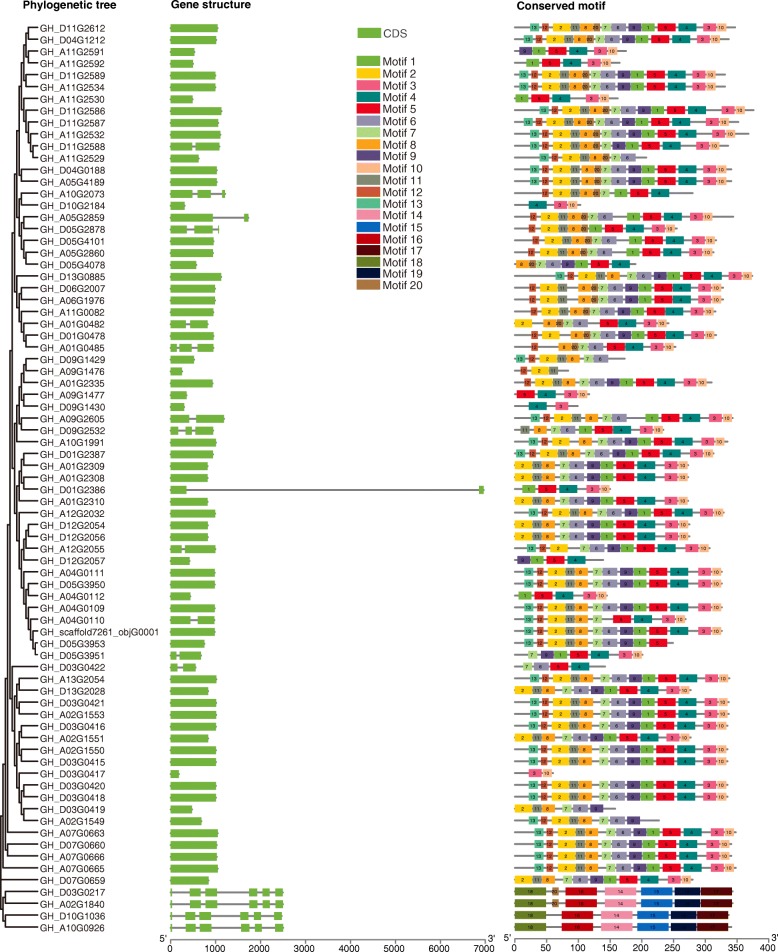

The gene structure of SOT genes was analyzed according to the gene annotation files and displayed in Fig. 5. Results showed that the exon numbers ranged from 1 to 6, with an average of 1.5. The great majority of genes contained less than 3 exons, and most contained only one exon. Classically, genes in the same evolutionary branch had similar structures, which shared a conserved gene structure pattern in terms of intron/exon number and intron/ exon length.

Fig. 5.

Conserved motif and gene structure of GhSOT genes. The phylogenetic tree was generated using protein sequences of 77 GhSOT genes. Intron/exon structure of SOT genes was analyzed by GSDS. Green boxes standed for exons; grey lines for introns. 20 conserved motifs were identified by MEME. Different color boxes with number represented different motifs

20 conserved motifs of GhSOT genes were identified through the MEME program (Fig. 5 and Additional file 1: Table S4), with a width ranged from 11 to 50 amino acids. The number of conserved motifs in different genes varied from 2 to 14, however, in the same branch of the phylogenetic tree, the number and type of conserved motifs were similar. Motif 4 appeared in 66 genes and was common to almost all GhSOT genes, followed by Motif 5, 3, 10, 7, 1 (appearing in more than 60 genes). The gene structures and conserved motifs of the four genes on the same evolutionary clade, GH_D03G0217, GH_A02G1840, GH_D10G1036 and GH_A10G0926, were different from other genes, which may lead to changes in evolutionary speed and function.

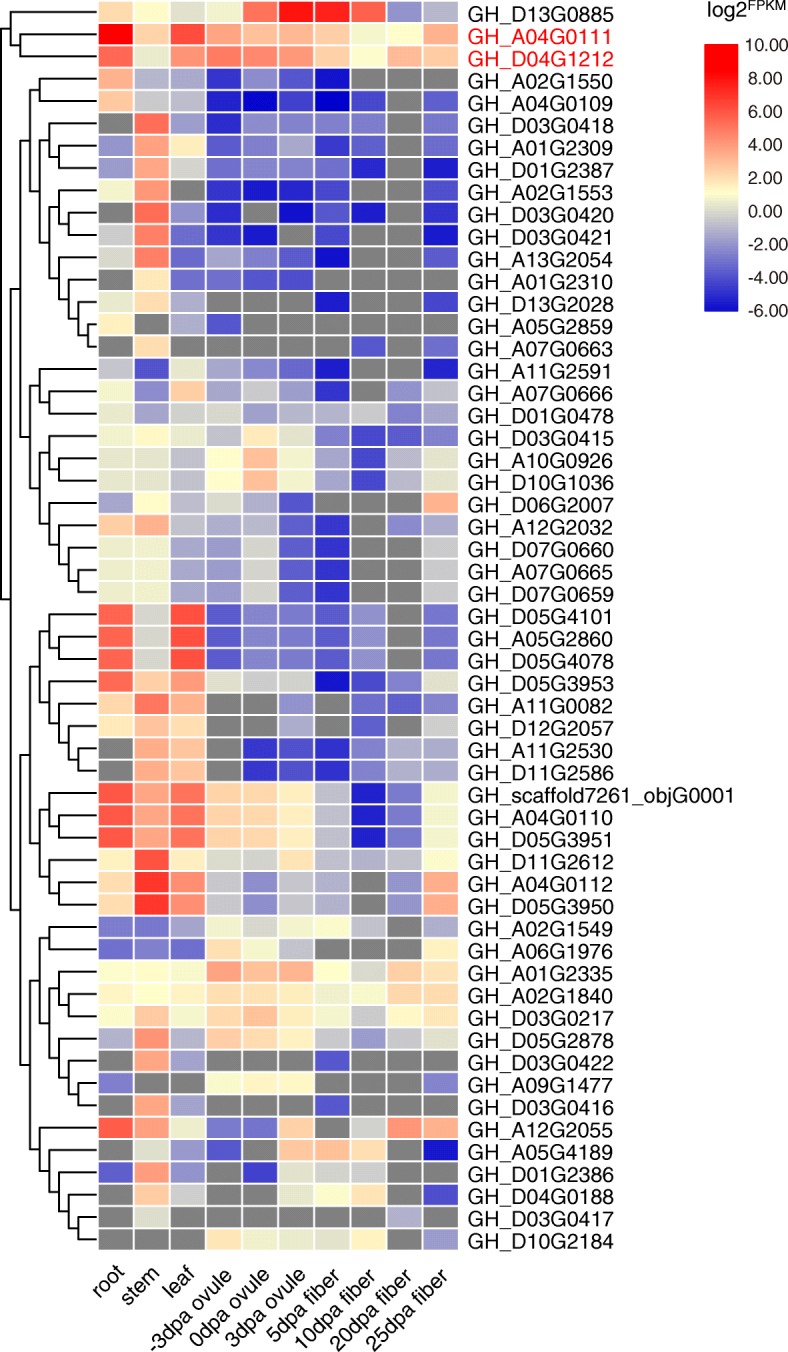

RNA-Seq expression profile of GhSOT genes

Firstly, 21 GhSOT genes with expression levels less than 1 at 10 different stages were eliminated. The raw data of the remaining 56 GhSOT genes were normalized to log2FPKM and the heatmap of the expression was shown in Fig. 6. Most genes exhibited characteristics that were specifically expressed during the different stages. 16 genes were constitutively expressed in 10 tissues, especially the expression values of GH_A04G0111 and GH_D04G1212 were more than 1 at all stages. Most of the GhSOT genes exhibited a high level of expression in the stem, leaf, and the initial stage of fiber development (− 3, 0, 3 dpa ovule). This indicated that SOT genes might be associated with fiber development in cotton. As reported in previous study [37], a lot of loci related with fiber quality were clustered on chromosomes D11. In this study, there were two SOT genes located on chromosomes D11, and one of them was specifically expressed in several tissues. So, we further performed experiments to understand the characteristics and functions of GhSOT67 (GH_D11G2586).

Fig. 6.

Transcriptome expression of GhSOT genes in different tissues and developmental stages (FPKM> 1). Expression levels were illustrated by graded color scale, red indicated high FPKM value, blue indicated low abundance, while grey indicated none expression. Genes marked in red represented constitutively and highly expression in 10 tissues

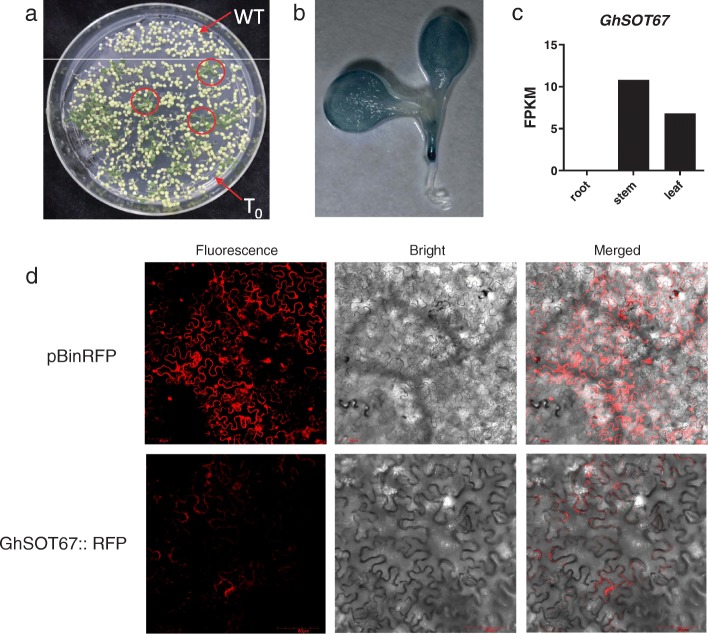

Tissue and subcellular localization analysis of GhSOT67

To investigate the tissue localization of GhSOT67, a recombinant vector of pGhSOT67::GUS was constructed and transformed into Arabidopsis mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells (GV3101). Multiple positive transformants were screened, soaked in the GUS staining solution and the most typical one was shown in Fig. 7a and b. The results showed that the staining in blue color was found in the stem and leaf of the transformant plant, which was consistent with the expression of the transcriptome expression of GhSOT67 (Fig. 7c). This expression pattern had also been reported in Arabidopsis [8].

Fig. 7.

Tissue and subcellular localization of GhSOT67. a Transformants were planted on half-strength MS medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin, the red circle showed the positive plants. b GUS staining analysis of the positive transgenic lines. c The FPKM value of GhSOT67 according to the transcriptome data. d Subcellular localization of RFP fusion proteins of GhSOT67 in infected tobacco leaves

According to the online tool CELLO, GhSOT67 was predicted to be localized in the cytoplasm (Additional file 1: Table S1). To verify this, full-length CDS of GhSOT67 without initial condon was ligated with pBinRFP vector. The control empty vector pBinRFP was present all over the cell, including the nucleus, membrane and cytoplasm (Fig. 7d). By contrast, the GhSOT67::RFP fusion protein was mainly localized in cytoplasm, confirming the previously predicted result.

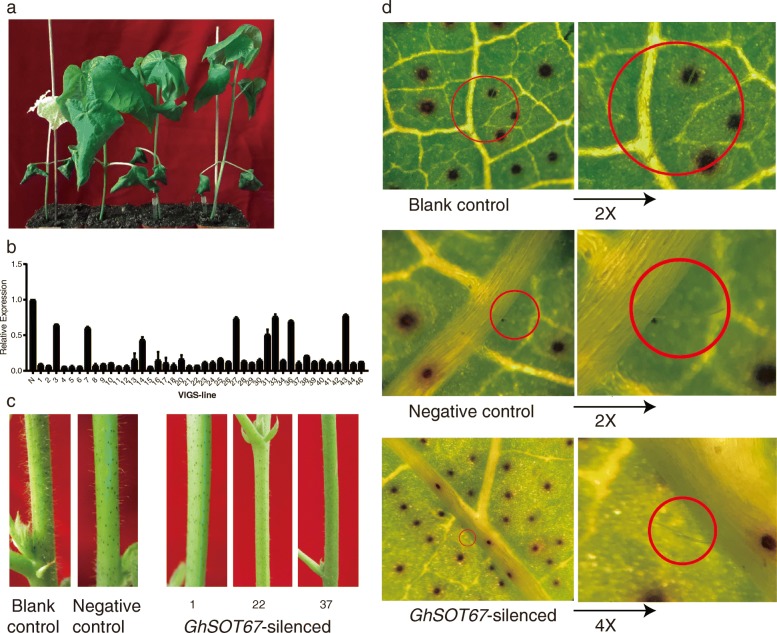

Virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of GhSOT67 in cotton

In order to investigate the relationship between GhSOT67 gene and fiber development, we performed VIGS on a cotton variety, J02. The empty vector pYL156 was used as a negative control. The recombinant vector pYL156:CLA1 could induce a leaf bleaching phenotype, therefore, it was served as a positive control to indicate the success of gene silencing.

17 days after the induction, the albino phenotype occurred on the positive control plants (Fig. 8a), proving that VIGS was successful. The expression of GhSOT67 after gene silencing was firstly verified by PCR compared with Histon3. Subsequently, the results of qRT-PCR revealed that the level of gene expression of most GhSOT67 silenced plants decreased by more than 80% (Fig. 8b). As shown in Fig. 8c, after 1 month of the treatment, the number of stem hairs in GhSOT67 silenced plant decreased evidently, comparing with the blank and negative control plants. In the meantime, the length of stem and leaf hairs of GhSOT67 silenced plants was obviously shorter than that of control plants (Fig. 8c and d). The stem and leaf hairs, as well as cotton seed fiber, were originated from the single cell layer, which might have similar fiber differentiation and development mechanisms [38–40]. Accordingly, the results suggested that GhSOT67 might be involved in the fiber development process.

Fig. 8.

Agrobacterium-mediated VIGS of GhSOT67 in cotton. a Phenotypes of gene silencing plants. The plants from left to right were CLA1-silenced, blank control, negative control and GhSOT67-silenced. b The expression levels of GhSOT67 in the negative control and silenced cotton plants conducted through qRT-PCR. N referred to the negtive control (Agrobacterial culture suspension of pYL156 only). c The stem hair of cotton after the induction. Left: blank control; Middle: negative control; Right: three lines of GhSOT67-silenced plant. d The leaf hairs of cotton observed under an optical microscopy after the induction. Upper: blank control under 10-fold visual field, the right one was the twice magnified leaf hair; Middle: negative control under 15-fold visual field, the right one was the double enlarged leaf hair; Lower: GhSOT67-silenced plant under 15-fold visual field, the right one was the fourfold enlarged leaf hair

Discussion

In recent years, the nuclear genome sequences of G. arboreum, G. raimondii, G. hirsutum, G. barbadense and G. hirsutum have been published successively [41–44], further deepening the understanding of cotton genomics and genetics, which provides a possibility for exploring SOT gene family members and their phylogenetic relationships. Here, we identified a total of 245 SOT genes from four cotton species, according to the sequence identity of proteins. The number of GhSOT and GbSOT genes were more than that of SOT genes in two diploid cotton, possibly due to the polyploidization event occurred in two tetraploid cotton about 1.5 million years ago (Mya) [36].

Gene duplication is considered to be the main driver of evolution, leading to functional differentiation and diversification [45]. Gene duplication mainly includes three forms such as tandem, whole-genome and segmental duplications. In this study, we found that tandem replication might primarily contribute to the expansion of the GhSOT gene family, as well as several other replication methods exist. On the bases of the previous reports in Arabidopsis, SOTs had been divided into 8 groups [1, 9]. Phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that 245 SOT genes from Gossypium were cluster with SOTs from Arabidopsis into 4 clades, except for 75 SOTs from Gossypium. The convergence of three genes at the end of the evolutionary branch was consistent with previous studies that two diploids were the ancestors of tetraploids [36]. The difference in the number of exons and conserved motifs between genes indicated that the gain and loss of exons may lead to the functional diversity of SOT genes closely related to the evolution of SOT gene family.

To date, only a few Arabidopsis SOTs were functionally characterized. At5g07000 from group VI was proved to catalyze the sulfation of 12-hydroxyjasmonates, thus causing inactivation of jasmonic acid in plants [16]. For another Arabidopsis SOT, At3g45070 from group II, had been found to specifically bind to flavonols [1]. For the GhSOT gene members, we paid particular attention to those that might play crucial roles in plant growth or fiber development. Combining the transcriptome expression of GhSOT genes with the fiber-quality-related loci reported previously [37], GhSOT67 was selected to further understand its characteristics and functions. For the localization analysis, GhSOT67 was estimated to express in cytoplasm and locate in stem and leaf tissue. These features would be related to its function as a catalyst [8]. Transcriptome expression showed that GhSOT67 was specifically expressed in several tissues and the initial stage of fiber development (− 3, 0, 3 dpa ovule). In addition, GhSOT67-silenced plants treated by VIGS showed a shorter length of stem and leaf hairs than that of control plants. According to the results of phylogenetic cluster, GhSOT67 belonged to group VI, it might have similar function to At5g07000 that can catalyze the inactivation of jasmonic acid. So we speculated that when GhSOT67 was silenced, jasmonic acid could not be sulfated and accumulated in the plant, then the length of stem and leaf hairs was shortened. Taken together, these results suggest that GhSOT67 may involve in cotton fiber development. However, the detailed correlation between SOTs, jasmonic acid and fiber development remains to be further verified.

Conclusion

In this study, a comprehensive analysis including chromosomal location, collinearity and duplication, gene structure and expression patterns of the SOT gene family in Gossypium was first performed. To summarise, we isolated a total of 245 SOT genes in the genome of G. arboreum, G. raimondii, G. barbadense and G. hirsutum, and further classified the SOT genes into four groups based on the orthologous relationships comparing with Arabidopsis. Tandem replication primarily contributed to the expansion of SOT gene family in G. hirsutum. Expression profiles of the GhSOTs in various tissue and developmental stages implied that GhSOTs might be involved in the fiber development. In addition, gene silencing by VIGS significantly induced the expression of GhSOT67 and shortened the length of stem and leaf hairs. Taken together, these findings indicated that SOT genes might be associated with fiber development in cotton.

Methods

Database search and sequence retrieval

The genome files and protein sequences of two diploid cottons [41, 46] (G. arboreum L., G. raimondii Ulbr.) and two tetraploid cottons [44] (G. hirsutum L., G. barbadense L.) were downloaded from the Cotton Functional Genomics Database (CottonFGD) (https://cottonfgd.org/) [47]. The protein sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) were obtained from the Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) (https://www.arabidopsis.org/). Based on the sequence similarity of the translated products, the Arabidopsis whole genome contains 21 genes encoding the SOT protein (AtSOT) [1] and all 21 Arabidopsis SOT proteins were extracted using TBtools (https://github.com/CJ-Chen/TBtools/releases) [48].

Two methods were used to search SOT genes in four cotton species. Firstly, 21 Arabidopsis SOT proteins were used as query sequences against the four cotton protein sequences files with default parameters (e-value <1e-5) through BLAST algorithm for Proteins (BLASTP) search. The candidate SOT genes of each cotton species were named separately, such as GhSOT from G. hirsutum and GbSOT from G. barbadens. Secondly, the hidden Markov model seed file (Stockholm format) of sulfotransferase domain (PF00685) were acquired from Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/) and used as a query sequence searching for candidate SOT protein sequences against the four cotton protein sequences files by Hmmer 3.0 (http://hmmer.org/), with default parameters. The SOT protein sequences with e-value less than 15 were preserved. Then, we merged all hits obtained above and discarded the repetitive sequences. All non-redundant protein sequences were further checked the conserved domains of the protein using the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cdd) in automatic mode (threshold = 0.01, maximum hits =500).

Finally, the candidate SOT genes were further manually confirmed to eliminate the pseudo sequences and the position in the cell was predicted according to the online tool CELLO v2.5 (http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/) [49]. The molecular weight (Mw) and isoelectric points (pI) of the candidate SOT genes were predicted using the online ExPASy server (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/) [50].

Chromosomal mapping and phylogenetic analysis

Chromosomal position and gene structure information of SOT genes were obtained from four cotton gene annotation files, and these SOT genes were mapped separately on the corresponding chromosomes using the MapChart software (https://www.wur.nl/en/show/Mapchart/).

The full-length amino acid sequence of the SOT genes from both Arabidopsis and Gossypium were saved as a fasta format file and used to perform multiple sequence alignments using the ClustalW program with the default settings. Subsequently, we constructed the neighbor-joining (NJ) tree in MEGA X, the parameters were set as follows: 1000 bootstrap replicates, Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) substitution model, and partial gap deletion mode with a cut-off value of 80%.

Intron/exon distribution and conserved motif analysis

The gene structure of SOT genes was analyzed using Gene Structure Display Server 2.0 (GSDS, http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) [51]. The conserved domain motifs of the SOTs were determined by Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme) [52] according to the following parameters: site distribution was set at 0 or 1 occurrence per sequence, the width of motifs ranged from 6 to 50, the maximum number of motifs was 20. All the characteristic results of SOT genes were visualized and integrated into graphics by Tbtools.

Gene expression analysis

The fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM) values were acquired from the transcriptome data of G. hirsutum cv. TM-1 [53]. The expression values of three different tissues and seven different stages of fiber development, − 3 dpa (day post anthesis) ovule, 0 dpa ovule, 3 dpa ovule as well as 5, 10, 20, and 25 dpa fibers, were considered and the genes with FPKM values more than 1 at least one stage were further analyzed. The expression of the SOT gene was estimated to be normalized in the form of log2FPKM and displayed in the heat map.

Plant materials

A cotton variety, J02, was provided by Germplasm Repository of Institute of Cotton Research, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CRI of CAAS, Anyang, Henan province, China) only for scientific research purpose. J02 was sown in mixed soil (vermiculite:humus = 1:1) and cultured in an incubator with a 16 h /8 h (light/ dark) photoperiod at 28 °C and 25 °C respectively till the cotyledons were fully unfolded.

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Colombia (Col-0) and tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) were also provided by CRI of CAAS and grown as recipient materials in the following ways. The seeds were grown on agar-solidified Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium by dropper, and after 48 h of hypothermia, the culture dishes were placed in an incubator with a 16 h / 8 h (light / dark) photoperiod at 24 °C and 22 °C respectively. When the cotyledons were unfolded, the seedlings were transplanted into sterile mixed soil (vermiculite:humus = 1:1).

Construction of target gene vectors and their inoculation treatment

In order to perform the tissue location of GhSOT67, 1500 bp promoter sequence upstream of the gene was amplified and inserted into the two restriction sites (HindIII and BamHI) of pBI121 vector. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens cells (GV3101) containing constructed vector was transformed into Arabidopsis plants according to the floral dip method [54]. The wildtype and transgenic plants were grown under conditions mentioned above. Positive transformants were screened by planting on half-strength MS medium containing 50 μg/mL kanamycin and confirmed by PCR and β-glucuronidase (GUS) staining.

The CDS of GhSOT67 without initial codon was inserted into the SalIrestriction site of the pBinRFP vector [55] to construct the translational RFP fusion constructs. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404 and inoculated into the second or third leaves on top of the tobacco according to the protocols [56]. The vector of pBinRFP (RFP alone) was also transformed into the tobacco leaves which was planted at the same time and in the same condition as the control. Finally, the infected tobacco leaves were wrapped in tinfoil, placed in a dark environment for 24–48 h and observed under an optical microscopy with CCD camera (Leica Microsystems, Germany) [57].

For the virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) experiment, an specific 300-bp sequence selected from the GhSOT67 was amplified with two restriction sites at both ends (SpeI and AscI). Firstly, the PCR amplification product was cloned into pMD19 T vector. Both the resultant construct and pYL156 were digested with SpeI and AscI, and connected through ligation buffer solutionI to form pYL156:GhSOT67. The plasmid was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens LBA4404 for infecting cotton. Agrobacterial culture suspension of pYL192 was respectively mixed with others equally as an auxiliary carrier. Agrobacterial culture suspension of pYL156 (negtive control), pYL156:CLA1 (positive control) and pYL156:GhSOT were separately injected into fully expanded cotyledons of cotton variety, J02, before the true leaves hadn’t yet emerged. Ten strains of J02 were reserved for wild type (blank control), 10 strains were injected with pYL156 and pYL156:CLA1 respectively, and 45 strains were injected with pYL156:GhSOT67. Experimental procedures and methods of operation were used as described by ref. [58].

Collections, RNA isolation and qRT-PCR analysis

About 2 weeks post infiltration, when true leaves appeared albino phenotype, the leaves of the J02 were put into the liquid nitrogen immediately and stored at − 80 °C for RNA isolation and analysis. Total RNA was extracted via the RNA extraction kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa, Japan). The quantitative real-time (qRT)-PCR analysis was completed on 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Inc., California USA) with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa, Japan). The Histon3 gene were used as an endogenous control to normalize gene expression. The relative expression levels of GhSOT67 gene after infiltration was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCT method [59].

All the gene-specific primers used for amplifications or vector constructions were listed in Additional file 1: Table S5.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Table S1. List of SOT genes identified in Gossypium and their sequence properties. Table S2. Duplicated SOT gene pairs among four cotton species. Table S3. Duplicated SOT gene pairs in G. hirsutum. Table S4. Informations of motifs in SOT genes. Table S5. Gene-specific primers used for amplifications or vector constructions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all colleagues in the lab for providing useful discussion and technical assistance. We are very grateful to the editors and reviewers for their critical evaluation of the manuscript and for providing constructive comments on its improvements.

Abbreviations

- APS

Adenosine-5′-phosphosulfate

- BLASTP

BLAST algorithm for proteins

- CDS

Coding sequence

- Chr

Chromosome

- CottonFGD

Cotton functional genomics database

- dpa

Days post anthesis

- FPKM

Fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped

- GSDS

Gene structure display server

- GUS

β-glucuronidase

- JTT

Jones-Taylor-Thornton

- Mb

millions of base pairs

- MEME

Multiple em for motif elicitation

- MS

Murashige and Skoog

- Mw

Molecular weights

- Mya

Million years ago

- NJ

neighbor-joining

- PAPS

3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate

- pI

Isoelectric points

- qRT-PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- SOTs

Sulfotransferases;

- TAIR

The Arabidopsis information resource

- VIGS

Virus-induced gene silencing

- WGD

Whole genome duplication

Authors’ contributions

XS and XD conceived and designed the research; LW performed the main experiments and bioinformatics analysis, wrote and revised the manuscript; XW and XL assisted in VIGS and qPCR experiments; ZP collected and cultivated all the plant materials, provided critical reagents for the experiments; XG and BL helped in VIGS and qPCR data analysis; XS and BC supervised the study, obtained funding and modified manuscript; and all authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Natural Science Foundation (ZR2017MC057) of Shandong Province, the National Key Research and Development Program (2018YFD0100303), the System of Modern Agriculture Industrial Technology (SDAIT-03-03/05), the Foundation for Innovative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31621005). All the funding bodies supported the design of this study, the data collection, analysis, interpretation and manuscript writing.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of the present study are included within this article (and its additional files). The authors are pleased to share any raw data upon request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The collection of plant materials used in our study complied with institutional and national guidelines. Field studies were conducted in accordance with local legislation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiongming Du, Email: dujeffrey8848@hotmail.com.

Xianliang Song, Email: songxl999@163.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12870-019-2190-3.

References

- 1.Klein M, Papenbrock J. In: Sulfur assimilation and abiotic stress in plants. Khan NA, Singh S, Umar S, editors. Berlin: springer; 2008. pp. 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roche P, Debellé F, Maillet F, Lerouge P, Faucher C, Truchet G, et al. Molecular basis of symbiotic host specificity in Rhizobium meliloti: nodH and nodPQ genes encode the sulfation of lipo-oligosaccharide signals. Cell. 1991;67:1131–1143. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90290-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coughtrie MWH, Sharp S, Maxwell K, Innes NP. Biology and function of the reversible sulfation pathway catalysed by human sulfotransferases and sulfatases. Chem Biol Interact. 1998;109:3–27. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varin L, Marsolais F, Richard M, Rouleau M. Sulfation and sulfotransferases 6: biochemistry and molecular biology of plant sulfotransferases. FASEB J. 1997;11:517–525. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.7.9212075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt A. Distribution of APS-sulfotransferase activity among higher plants. Plant Sci Lett. 1975;5:407–415. doi: 10.1016/0304-4211(75)90008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glendening TM, Poulton JE. Partial purification and characterization of a 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate: desulfoglucosinolate sulfotransferase from cress (Lepidium sativum) Plant Physiol. 1990;94:811–818. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.2.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varin L, DeLuca V, Ibrahim RK, Brisson N. Molecular characterization of two plant flavonol sulfotransferases. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1992;89:1286–1290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacomme C, Roby D. Molecular cloning of a sulfotransferase in Arabidopsis thaliana and regulation during development and in response to infection with pathogenic bacteria. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;30:995–1008. doi: 10.1007/BF00020810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein M, Papenbrock J. The multi-protein family of Arabidopsis sulphotransferases and their relatives in other plant species. J Exp Bot. 2004;55:1809–1820. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baek D, Pathange P, Chung JS, Jiang J, Gao L, Oikawa A, et al. A stress-inducible sulphotransferase sulphonates salicylic acid and confers pathogen resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:1383–1392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamashino T, Kitayama M, Mizuno T. Transcription of ST2A encoding a sulfotransferase family protein that is involved in jasmonic acid metabolism is controlled according to the circadian clock- and PIF4/PIF5-mediated external coincidence mechanism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77:2454–2460. doi: 10.1271/bbb.130559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirschmann F, Krause F, Papenbrock J. The multi-protein family of sulfotransferases in plants: composition, occurrence, substrate specificity, and functions. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirschmann F, Papenbrock J. The fusion of genomes leads to more options: a comparative investigation on the desulfo-glucosinolate sulfotransferases of Brassica napus and homologous proteins of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2015;91:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang QH, Hao RJ, Zheng Z, Deng YW, Du XD. Cloning and function of sulfotransferase gene PmCHST1a in Pinctada martensii. J Fish China. 2017;41:669–677. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinshilboum RM, Otterness DM, Aksoy IA, Wood TC, Her C, Raftogianis RB. Sulfation and sulfotransferases 1: Sulfotransferase molecular biology: cDNAs and genes. FASEB J. 1997;11:3–14. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.1.9034160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gidda SK, Miersch O, Levitin A, Schmidt J, Wasternack C, Varin L. Biochemical and molecular characterization of a hydroxyjasmonate sulfotransferase from Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17895–17900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pornsiriwong W, Estavillo GM, Chan KX, Tee EE, Ganguly D, Crisp PA, et al. A chloroplast retrograde signal, 3’phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate, acts as a secondary messenger in abscisic acid signaling in stomatal closure and germination. ELife. 2017;6:1–34. doi: 10.7554/eLife.23361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao CC, Wang YY, Chan KX, Marchant DB, Franks PJ, Randall D, et al. Evolution of chloroplast retrograde signaling facilitates green plant adaptation to land. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116(11):5015–5020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1812092116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen RJ, Jiang YY, Dong JL, Zhang X, Xiao HB, Xu ZJ, et al. Genome-wide analysis and environmental response profiling of SOT family genes in rice (Oryza sativa) Genes Genomics. 2012;34:549–560. doi: 10.1007/s13258-012-0053-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen ZJ, Scheffler BE, Dennis E, Triplett BA, Zhang TZ, Guo WZ, et al. Toward sequencing cotton (Gossypium) genomes. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:1303–1310. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.107672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang L, Wang Q, Hu Y, Jia YH, Chen JD, Liu BL, et al. Genomic analyses in cotton identify signatures of selection and loci associated with fiber quality and yield traits. Nat Genet. 2017;49(7):1089–1098. doi: 10.1038/ng.3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuan YC, Zhang HJ, Wang LY, Xing HX, Mao LL, Tao JC, et al. Candidate quantitative trait loci and genes for fiber quality in Gossypium hirsutum L. detected using single- and multi-locus association mapping. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019;134:356–369. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim HJ. Triplett B a. cotton fiber growth in planta and in vitro. Models for plant cell elongation and cell wall biogenesis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1361–1366. doi: 10.1104/pp.010724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Wang HY, Zhao PM, Han LB, Jiao GL, Zheng YY, et al. Overexpression of a profilin (GhPFN2) promotes the progression of developmental phases in cotton fibers. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010;51:1276–1290. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcq086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JJ, Woodward AW, Chen ZJ. Gene expression changes and early events in cotton fibre development. Ann Bot. 2007;100:1391–1401. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan JF, Tu LL, Deng FL, Hu HY, Nie YC, Zhang XL. A genetic and metabolic analysis revealed that cotton fiber cell development was retarded by flavonoid naringenin. Plant Physiol. 2013;162:86–95. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.212142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu HF, Luo C, Song W, Shen HT, Li GL, He ZG, et al. Flavonoid biosynthesis controls fiber color in naturally colored cotton. Peer J. 2018;6:e4537. doi: 10.7717/peerj.4537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen ZJ, Guan XY. Auxin boost for cotton. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:407–409. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao GH, Zhao P, Zhang Y. A pivotal role of hormones in regulating cotton fiber development. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Tan JF, Tu LL, Deng FL, Wu R, Zhang XL. Exogenous jasmonic acid inhibits cotton fiber elongation. J Plant Growth Regul. 2012;31:599–605. doi: 10.1007/s00344-012-9260-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hao J, Tu LL, Hu HY, Tan JF, Deng FL, Tang WX, et al. GbTCP, a cotton TCP transcription factor, confers fibre elongation and root hair development by a complex regulating system. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:6267–6281. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li C, He X, Luo XY, Xu L, Liu LL, Min L, et al. Cotton WRKY1 mediates the plant defense-to-development transition during infection of cotton by Verticillium dahliae by activating JASMONATE ZIM-DOMAIN1 expression. Plant Physiol. 2014;166:2179–2194. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.246694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hu HY, He X, Tu LL, Zhu LF, Zhu ST, Ge ZH, et al. GhJAZ2 negatively regulates cotton fiber initiation by interacting with the R2R3-MYB transcription factor GhMYB25-like. Plant J. 2016;88:921–935. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W, Cheng YY, Chen DD, Liu D, Hu MJ, Dong J, et al. The catalase gene family in cotton: genome-wide characterization and bioinformatics analysis. Cells. 2019;8:86. doi: 10.3390/cells8020086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen Q, Chen QJ, Sun GQ, Zheng K, Yao ZP, Han YH, et al. Genome-wide identification of cyclophilin gene family in cotton and expression analysis of the fibre development in Gossypium barbadense. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:349. doi: 10.3390/ijms20020349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wendel JF, Clark CR. Polyploidy and the evolutionary history of cotton. Adv Agron. 2003;78:139. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2113(02)78004-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma ZY, He SP, Wang XF, Sun JL, Zhang Y, Zhang GY, et al. Resequencing a core collection of upland cotton identifies genomic variation and loci influencing fiber quality and yield. Nat Genet. 2018;50:803–813. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagner GJ, Wang E, Shepherd RW. New approaches for studying and exploiting an old protuberance, the plant trichome. Ann Bot. 2004;93:3–11. doi: 10.1093/aob/mch011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guan XY, Song QX, Chen ZJ. Polyploidy and small RNA regulation of cotton fiber development. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:516–528. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X, Hu DP, Li Y, Chen Y, Abidallha EHMA, Dong ZD, et al. Developmental and hormonal regulation of fiber quality in two natural-colored cotton cultivars. J Integr Agric. 2017;16:1720–1729. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(16)61504-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du XM, Huang G, He SP, Yang ZE, Sun GF, Ma XF, et al. Resequencing of 243 diploid cotton accessions based on an updated a genome identifies the genetic basis of key agronomic traits. Nat Genet. 2018;50:796–802. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang KB, Wang ZW, Li FG, Ye WW, Wang JY, Song GL, et al. The draft genome of a diploid cotton Gossypium raimondii. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1098–1103. doi: 10.1038/ng.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang MJ, Tu LL, Yuan DJ, Zhu D, Shen C, Li JY, et al. Reference genome sequences of two cultivated allotetraploid cottons, Gossypium hirsutum and Gossypium barbadense. Nat Genet. 2019;51:224–229. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0282-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu Y, Chen JD, Fang L, Zhang ZY, Ma W, Niu YC, et al. Gossypium barbadense and Gossypium hirsutum genomes provide insights into the origin and evolution of allotetraploid cotton. Nat Genet. 2019;51:739–748. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lynch M, Conery JS. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000;290:1151–1156. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paterson AH, Wendel JF, Gundlach H, Guo H, Jenkins J, Jin DC, et al. Repeated polyploidization of Gossypium genomes and the evolution of spinnable cotton fibres. Nature. 2012;492:423–427. doi: 10.1038/nature11798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu T, Liang CZ, Meng ZG, Sun GQ, Meng ZH, Guo SD, et al. CottonFGD: an integrated functional genomics database for cotton. BMC Plant Biol. 2017;17:101. doi: 10.1186/s12870-017-1039-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen CJ, Chen H, He YH, Xia R. TBtools, a Toolkit for Biologists integrating various biological data handling tools with a user-friendly interface. bioRxiv. 2018:289660.

- 49.Li HZ. A model of local-minima distribution on conformational space and its application to protein structure prediction. Proteins. 2006;64(4):985–991. doi: 10.1002/prot.21084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gasteiger E, Hoogland C, Gattiker A, Duvaud S, Wilkins MR, Appel RD, et al. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server. In: The proteomics protocols handbook. In; 2009. p. 571–607.

- 51.Hu B, Jin JP, Guo AY, Zhang H, Luo JC, Gao G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1994;2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang TZ, Hu Y, Jiang WK, Fang L, Guan XY, Chen JD, et al. Sequencing of allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. acc. TM-1) provides a resource for fiber improvement. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:531–537. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clough SJ, Bent FA. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu TL, Song TQ, Zhang X, Yuan HB, Su LM, Li WL, et al. Unconventionally secreted effectors of two filamentous pathogens target plant salicylate biosynthesis. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4686. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sparkes IA, Runions J, Kearns A, Hawes C. Rapid, transient expression of fluorescent fusion proteins in tobacco plants and generation of stably transformed plants. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(4):2019–2025. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang W, Wang SY, Yu FW, Tang J, Shan X, Bao K, et al. Genome-wide characterization and expression profiling of SWEET genes in cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata L.) reveal their roles in chilling and clubroot disease responses. BMC Genomics. 2019;20:93. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5454-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gao XQ, Britt RC Jr, Shan LB, He P. Agrobacterium-mediated virus-induced gene silencing assay in cotton. J Vis Exp. 2011:e2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2− ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. List of SOT genes identified in Gossypium and their sequence properties. Table S2. Duplicated SOT gene pairs among four cotton species. Table S3. Duplicated SOT gene pairs in G. hirsutum. Table S4. Informations of motifs in SOT genes. Table S5. Gene-specific primers used for amplifications or vector constructions.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of the present study are included within this article (and its additional files). The authors are pleased to share any raw data upon request.