Abstract

Rationale: Intraerythrocytic polymerization of Hb S promotes hemolysis and vasoocclusive events in the microvasculature of patients with sickle cell disease (SCD). Although platelet–neutrophil aggregate–dependent vasoocclusion is known to occur in the lung and contribute to acute chest syndrome, the etiological mechanisms that trigger acute chest syndrome are largely unknown.

Objectives: To identify the innate immune mechanism that promotes platelet–neutrophil aggregate–dependent lung vasoocclusion and injury in SCD.

Methods: In vivo imaging of the lung in transgenic humanized SCD mice and in vitro imaging of SCD patient blood flowing through a microfluidic system was performed. SCD mice were systemically challenged with nanogram quantities of LPS to trigger lung vasoocclusion.

Measurements and Main Results: Platelet–inflammasome activation led to generation of IL-1β and caspase-1–carrying platelet extracellular vesicles (EVs) that bind to neutrophils and promote platelet–neutrophil aggregation in lung arterioles of SCD mice in vivo and SCD human blood in microfluidics in vitro. The inflammasome activation, platelet EV generation, and platelet–neutrophil aggregation were enhanced by the presence of LPS at a nanogram dose in SCD but not control human blood. Inhibition of the inflammasome effector caspase-1 or IL-1β pathway attenuated platelet EV generation, prevented platelet–neutrophil aggregation, and restored microvascular blood flow in lung arterioles of SCD mice in vivo and SCD human blood in microfluidics in vitro.

Conclusions: These results are the first to identify that platelet–inflammasome–dependent shedding of IL-1β and caspase-1–carrying platelet EVs promote lung vasoocclusion in SCD. The current findings also highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting the platelet–inflammasome–dependent innate immune pathway to prevent acute chest syndrome.

Keywords: acute chest syndrome, vasoocclusion, neutrophil–platelet aggregates

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Acute chest syndrome is a type of acute lung injury and one of the leading causes of mortality in sickle cell disease (SCD). The current treatment for acute chest syndrome is primarily supportive, and the etiological mechanism remains poorly understood. Recent evidence suggests that acute chest syndrome is often a sequela of acute systemic painful vasoocclusive crisis and could result from vasoocclusion of the lung microvasculature by neutrophil and platelet aggregates. However, the innate immune pathway that promotes platelet–neutrophil aggregation in the SCD pulmonary microvasculature remains largely unknown.

What This Study Adds to the Field

The current study uses in vivo imaging of lung in transgenic humanized SCD mice and live-cell imaging of SCD patient blood flowing in vitro to identify, for the first time, that platelet–inflammasome activation in SCD promotes shedding of IL-1β and caspase-1–carrying platelet extracellular vesicles. Platelet extracellular vesicles contribute to lung vasoocclusion and injury in SCD by promoting IL-1β–dependent platelet–neutrophil aggregation in the lung microvasculature. These findings suggest that therapeutic inhibition of the platelet–inflammasome– and IL-1β–dependent innate immune pathway can be a promising therapy for acute chest syndrome.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a monogenic disorder that affects more than 3 million people worldwide (1, 2). Sickle cell anemia, the most common form of SCD, is caused by a homozygous mutation (SS) in the β-globin gene (1, 3). The mutant Hb polymerizes upon deoxygenation to form bundles, leading to erythrocyte rigidity, dehydration, vasoocclusion, and premature hemolysis (1). Vasoocclusion promotes the development of acute systemic painful vasoocclusive crisis, which is the primary reason for emergency medical care among patients with SCD (1). Clinical evidence suggests that vasoocclusive crisis can also progress to acute chest syndrome, a type of acute lung injury and one of the leading causes of mortality (1, 4, 5). Recently (6), we found that vasoocclusive crisis in transgenic, humanized SCD mice led to occlusion of pulmonary arterioles by platelet–neutrophil aggregates. Our finding was supported by an independent histopathology study that identified platelet aggregates occluding pulmonary arterioles in patients with acute chest syndrome (7). Altogether, these findings suggest that vasoocclusive crisis in SCD promotes pulmonary vasoocclusion mediated by platelet–neutrophil aggregates, and the development of acute chest syndrome can be prevented provided therapies to treat pulmonary vasoocclusion are identified.

Hemolysis promotes an inflammatory milieu in SCD by releasing erythrocyte-derived damage-associated molecular pattern molecules (DAMPs), such as Hb and heme (8), that scavenge nitric oxide, generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and “prime” TLR4 (toll-like receptor 4)-dependent innate immune signaling in vascular cells (9, 10). We recently (6) found that nanogram levels of the TLR4 ligand, bacterial LPS, selectively promoted P-selectin–dependent platelet–neutrophil aggregation in SCD human blood in vitro and platelet–neutrophil aggregate–mediated occlusion of pulmonary arterioles in SCD mice in vivo. These findings are also consistent with the clinical presentation in patients with SCD who are susceptible to acute chest syndrome after exposure to less severe triggers than healthy humans (4, 11–13) and evidence of activated leukocytes and platelets in SCD patient blood (6, 14–20). A recent study (20) demonstrated translocation of low levels of bacterial TLR4 ligands from the gut into the blood circulation promoting vasoocclusion in SCD mice. Taken together, these findings suggest that DAMPs-mediated priming of innate immune pathways in SCD may set a lower threshold for platelet–neutrophil aggregation after exposure to low levels of pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules, such as TLR4 ligands. However, the innate immune mechanism that promotes such priming and catalyzes P-selectin–dependent platelet–neutrophil aggregation in the SCD pulmonary microvasculature remains largely unknown.

Here, we use quantitative fluorescence intravital lung microscopy (qFILM) (21) in SCD mice and in vitro quantitative microfluidic fluorescence microscopy (qMFM) (22) with flowing SCD human blood to reveal that the activation of platelet NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain-containing 3) inflammasome promotes the shedding of IL-1β and caspase-1–carrying extracellular vesicles (EVs) by platelets in SCD. Platelet EVs activate neutrophils, other platelets, and vascular cells in an IL-1β and caspase-1–dependent manner to form large platelet–neutrophil aggregates that occlude pulmonary arterioles. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of abstracts (23, 24).

Methods

Refer to the online supplement for full description of methods.

Blood Collection

Healthy race-matched control human subjects (control) and steady state (not in crisis) SCD (SS or S/β0) patient blood was collected in accordance with the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pittsburgh under the Institutional Review Board protocol PRO08110422.

qMFM

qMFM experimental design, sample preparation, and setup has been described elsewhere (6, 22, 25). Heparinized human blood (500 μl) was perfused through the microfluidic flow channels, presenting a combination of P-selectin, ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule-1), and IL-8, at a physiological (26, 27) wall shear stress of 6 dyn ⋅ cm−2. Neutrophil–platelet interactions were analyzed as described in the online supplement.

Mice

Male and female (age ∼12–16 wk) Townes SCD mice (SS) and non-sickle mice (AS) were used as SCD and control mice, respectively (28–30). Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh.

qFILM

The qFILM experimental design has been described previously (6, 21). Briefly, control and SCD mice were intravenously injected via tail vein with one of the following: 1) saline, 2) 0.1 μg/kg LPS, 3) 0.002 μmol/kg caspase-1 inhibitor (YVAD-CHO) followed by 0.1 μg/kg LPS, 4) 1 or 5 mg/kg IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) with 0.1 μg/kg LPS, 5) unstained or Chloromethyl-dialkylcarbocyanine stained SCD or control platelet EVs, 6) SCD platelet EVs with 0.004 μmol/kg YVAD-CHO, or 7) SCD platelet EVs with 10 mg/kg IL-1RA. Mice were anesthetized and qFILM was performed as described in the online supplement.

Isolation and Western Blot Analysis of Human Platelets

Please refer to the online supplement for details.

Analysis of Platelet EV Generation in Human Platelet-Rich Plasma

Samples of control and SCD human platelet-rich plasma were treated accordingly: 1) no treatment, 2) 0.25 μg/ml LPS, 3) 200 μM YVAD-CHO, or 4) 0.25 μg/ml LPS and 200 μM YVAD-CHO. Total and platelet-derived EVs were prepared from platelet-poor plasma using the method described in the online supplement.

IL-1β and Caspase-1 Estimation in Platelet EVs

EV suspension was treated with Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (MPER; ThermoFisher Scientific) and the IL-1β levels in the suspensions were measured using ELISA. Caspase-1 was detected using Western blots. Details are in the online supplement.

Isolation of Platelet EVs from Mice

SCD mice were intravenously administered 1 μg/kg LPS. Three hours later, blood was collected and processed to obtain platelet-poor plasma. Stained or unstained total and platelet-derived EVs were prepared from platelet-poor plasma using the method described in the online supplement.

NLRP3 and Apoptosis-associated Speck-like Protein Containing a Caspase Recruitment Domain Colocalization Analysis

Platelet-rich plasma prepared from SCD or control human blood was either left untreated or treated with 0.25 μg/ml LPS for 30 minutes. Platelets were attached to glass slides, fixed using a fixative cocktail, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X 100 (Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were stained with primary antibodies (Abs) against NLRP3 and apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC) followed by Cy3 and Cy5-conjugated secondary Abs. Samples were imaged using Nikon A1R laser confocal microscope. Details are in the online supplement.

Statistics

Means were compared between groups using the unpaired Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons. Percentages were compared using fourfold table analysis with χ2 statistics as described elsewhere (6, 31, 32). Error bars represent SE. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Inflammatory Milieu in SCD Promotes Activation of Platelet Inflammasome

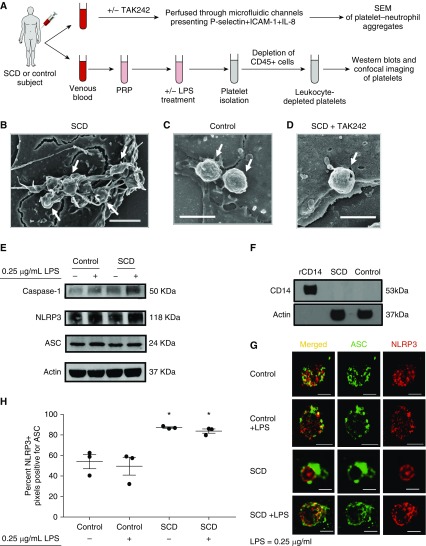

Control and SCD human blood was perfused at a physiological shear stress (26, 27) of 6 dyn ⋅ cm−2 (0.6 Pa) through in vitro microfluidic flow channels presenting a combination of P-selectin, ICAM-1, and IL-8. Table 1 shows clinical characterization of human subjects used in the entire study. Neutrophils were observed to roll, arrest, and then interact with freely flowing platelets, leading to the formation of platelet–neutrophil aggregates. When these aggregates were fixed under flow and visualized using scanning electron microscopy (Figure 1A, experimental scheme #1), we found large aggregates of platelets adhered to neutrophils in SCD human blood (see Figures 1B and E1A–E1C in the online supplement). Remarkably, these SCD platelets were covered with membrane protrusions, which are hallmarks of platelet activation, degranulation, and EV shedding. In contrast, individual, rather than aggregates of, platelets were adhered to neutrophils in control human blood, and these control platelets manifested a “round” morphology suggestive of quiescent platelets (see Figures 1C and E1D–E1F). Interestingly, treatment of SCD blood with TLR4 antagonist (TAK242) led to absence of platelet aggregates, loss of membrane protrusions, and rescue of round morphology in platelets (see Figures 1D and E1G–E1I), suggesting that the inflammatory milieu in SCD promotes TLR4-dependent activation of platelets.

Table 1.

Clinical Characterization of Human Subjects

| Control | SCD | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, F/M | 7/4 | 12/10 |

| Age, yr | 36 (32; 27; 61) | 35 (32.5; 22; 60) |

| Hb, g/dl | 13.4 (13.6; 9.7; 16.7) | 8.92 (9.25; 5.8; 13.2) |

| Hematocrit, % | 42.16 (42.5; 32.7; 49.1) | 26.38 (26.7; 17; 39.4) |

| White blood cells, ×1,000/μl | 5.42 (5.6; 3.5; 7.54) | 10.31 (9.7; 3.9; 27.6) |

| Neutrophils, % | 45.13 (49.61; 20.91; 62.32) | 51.58 (50.4; 29; 75.3) |

| Neutrophil count, ×1,000/μl | 2.51 (2.15; 0.8; 4.7) | 5.57 (4.2; 1.7; 19.87) |

| Platelets, ×1,000/μl | 145.56 (142.5; 64; 243) | 320.8 (286; 122; 622) |

| HbS, % | N/M | 59.86 (56.7; 8.6; 80) |

| HbF, % | N/M | 17.98 (20; 2.5; 35) |

| Genotypes | ||

| AA | 10 | 0 |

| AS | 1 | 0 |

| SS | 0 | 18 |

| S/β0 | 0 | 4 |

| Hydroxyurea, yes/no | N/A | 16/6 |

Definition of abbreviations: AA = healthy control; AS = sickle cell trait; HbF = fetal Hb; HbS = sickle Hb; N/A = not applicable; N/M = not measured; S/β0 = sickle β0 thalassemia; SCD = sickle cell disease; SS = sickle cell anemia.

Data shows mean (median; minimum; maximum) except for the sex, genotype, and hydroxyurea status.

Figure 1.

Inflammatory milieu in sickle cell disease (SCD) promotes activation of platelet inflammasome. (A) Experimental scheme #1: SCD or control human blood with or without treatment with TLR4 (toll-like receptor 4) inhibitor TAK242 (50 μg/ml) was perfused through microfluidic flow channels presenting a combination of P-selectin, ICAM-1, and IL-8. Platelet–neutrophil aggregates were fixed under flow and visualized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Experimental scheme #2: Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was prepared from SCD or control human blood. PRPs were left untreated or treated with LPS (0.25 μg/ml). Platelets were isolated from untreated or LPS-treated PRPs and depleted of leukocytes (cluster of differentiation [CD]-45+ cells) before use in Western blots or confocal microscopy. Refer to the online supplement for details. (B–D) Scanning electron micrographs show platelets (arrows) nucleated on top of an arrested neutrophil in SCD human blood (B), control human blood (C), and SCD human blood treated with TAK242 (50 μg/ml) (D) (scale bar, 2.5 μm; wall shear stress, 6 dyn ⋅ cm−2). (E) Representative Western blot micrograph shows the presence of NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing-3) (118 kD), apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase recruitment domain (ASC) (24 kD), and caspase-1 (50 kD) in both control and SCD platelets. Complete gels and densitometry analysis are shown in Figure E2 and E3, respectively. (F) Representative Western blot micrograph shows absence of CD14 (53 kD) in SCD and control human platelet samples. Recombinant human CD14 in lane 1 was used as a standard positive control. Complete gels are shown in Figure E4. β-Actin (37 kD) was used as the housekeeping control in E and F. (G) Representative confocal microscopy images shows the colocalization of ASC (green) and NLRP3 (red) in control and SCD platelets with or without treatment with 0.25 μg/ml LPS (scale bars, 2 μm). (H) Confocal images of three cells in each treatment group were analyzed to determine the percentage of NLRP3 positive (red) pixels that were also positive for ASC (green). Each data point represents an individual platelet. Mean values for each group were plotted and compared using the Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction. (B–H) Data shown are representative of experiments done with blood samples of two control and two SCD subjects (B–D and Figure E1), three control and three SCD subjects (E and Figure E3), one SCD and one control subject (F), and two control and two SCD subjects (G–H). *P < 0.05 when compared with control. ICAM-1 = intercellular adhesion molecule-1.

TLR4 activation is known to prime the inflammasome pathway in leukocytes by promoting transcription-dependent intracellular upregulation of inflammasome components (33). Ironically, platelets lack a nucleus and, therefore, cannot perform the canonical two-step (priming and activation) activation of inflammasome that occurs in leukocytes (34, 35). However, the NLRP3-inflammasome (33) containing NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 is constitutively expressed in platelets (34, 35). We determined whether platelet TLR4 activation also contributes to platelet NLRP3-inflammasome activation in SCD. Previously (6), we have shown that pretreatment with LPS at a concentration of 0.25 μg/ml was potent enough to significantly increase platelet–neutrophil aggregation in SCD human blood flowing through microfluidic flow channels in vitro, but a fourfold higher concentration of LPS (1 μg/ml) was required to promote aggregation in control human blood. Therefore, platelets were isolated from SCD or control human platelet-rich plasma with or without pretreatment with 0.25 μg/ml LPS (see Figure 1A, experimental scheme #2). Western blots confirmed the presence of NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 in both control and SCD human platelets (see Figure 1E). Complete gels and densitometry analysis are shown in Figures E2 and E3, respectively. The likelihood of monocyte contamination was excluded by depleting platelet samples of leukocytes (cluster of differentiation [CD]-45+ cells; see Figure 1A, experimental scheme #2) and confirming the absence of monocyte marker CD14 in platelet lysates (see Figure 1F; complete gels in Figure E4). Next, we used colocalization of NLRP3 with ASC as a marker for inflammasome activation (33, 34). Confocal microscopy revealed that NLRP3 (red) and ASC (green) each displayed randomly punctate distribution with minimal overlap in both untreated and 0.25 μg/ml LPS-treated control human platelets (see Figure 1G, top two rows). In contrast, both ASC (green) and NLRP3 (red) appeared colocalized in untreated SCD platelets (see Figure 1G, red and green overlapping rings in third row), and 0.25 μg/ml LPS-treated SCD platelets (see Figure 1G; several regions of the merged image in the bottom row appear yellow owing to overlap of green with red). Specificity of staining was confirmed by the lack of staining in samples treated with only secondary Abs (Figure E5). Colocalization of NLRP3 with ASC was quantified based on the percentage of NLRP3-positive (red) pixels that were also positive for ASC (green). As shown in Figure 1H, the colocalization of NLRP3 with ASC was significantly higher in SCD than control human platelets, both at baseline and after pretreatment with 0.25 μg/ml LPS. Western blot analysis confirmed the presence of cleaved caspase-1 in LPS-treated SCD human platelets (Figure E6).

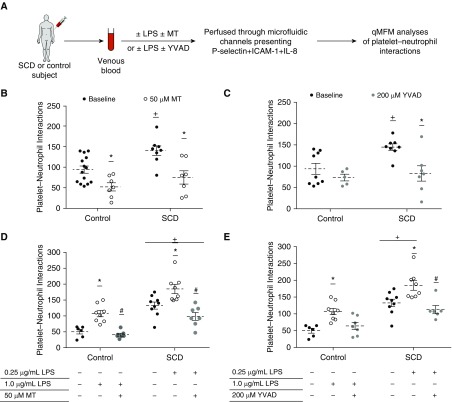

Platelet Inflammasome Promotes Platelet–Neutrophil Aggregation in SCD

Mitochondrial ROS (mtROS), a potent activator of the NLRP3 inflammasome (33, 36), has been shown to be significantly elevated in platelets of patients with SCD (14). Mitotempo is a mtROS scavenger (14) that has been used widely to inhibit NLRP3-inflammasome activation (36). YVAD-CHO, a caspase-1 inhibitor, has also been used widely to inhibit the NLRP3-inflammasome pathway (37). As shown in an experimental scheme (Figure 2A), SCD or control human blood with or without treatment with 50 μM Mitotempo or 200 μM YVAD-CHO was perfused through microfluidic flow channels presenting a combination of P-selectin, ICAM-1, and IL-8. Platelet–neutrophil aggregation was assessed using qMFM based on the following two parameters (6, 22): total platelet–neutrophil interactions per field of view (FOV; ∼14,520 μm2) and total platelet–neutrophil interactions per arrested neutrophil. Mitotempo significantly reduced the total number of platelet–neutrophil interactions in both untreated control and SCD human blood (see Figure 2B). Mitotempo also significantly reduced the number of platelet interactions per arrested neutrophil in SCD human blood (Figure E7A). Remarkably, caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD-CHO significantly reduced the total platelet–neutrophil interactions (see Figure 2C) and platelet interactions per neutrophil (see Figure E7B) in SCD human blood while having no effect on control human blood.

Figure 2.

Platelet inflammasome promotes platelet–neutrophil aggregation in SCD human blood. (A) Experimental scheme: Either untreated or LPS-treated control and SCD human blood with or without additional treatment with mitochondrial reactive oxygen species scavenger Mitotempo (MT) or caspase-1 inhibitor (YVAD) was perfused through microfluidic flow channels presenting P-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and IL-8. Neutrophils were observed to roll, arrest, crawl, and interact with freely flowing platelets, resulting in significantly more platelet–neutrophil interactions in untreated SCD than control blood. Platelet–neutrophil aggregation was assessed using qMFM and compared between groups using the following two parameters: average number of platelets that interact with arrested neutrophils per field of view (FOV; ∼14,520 μm2) over a 2-minute period (shown here) and average number of platelets interacting per arrested neutrophil over a 2-minute period (Figure E7). Wall shear stress is 6 dyn ⋅ cm−2. Refer to the online supplement for details. (B) The effect of MT (50 μM) on platelet–neutrophil interactions per FOV in untreated control and SCD human blood is shown. (C) The effect of YVAD (200 μM) on platelet–neutrophil interactions per FOV in untreated control and SCD human blood is shown. (D and E) As depicted in the experimental scheme, experiments shown in B and C were also repeated with control and SCD human blood pretreated with 1 μg/ml and 0.25 μg/ml LPS, respectively. Refer to the online supplement for details. (D) The effect of MT (50 μM) on platelet–neutrophil interactions per FOV and (E) the effect of YVAD (200 μM) on platelet–neutrophil interactions per FOV in control and SCD human blood pretreated with 1 μg/ml and 0.25 μg/ml of LPS, respectively, are shown. Means were compared using the Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Each data point in B–E represents total interactions in an FOV. (B–E) Data are representative of four control human subjects and three human subjects with SCD (B), three control human subjects and four human subjects with SCD (C), three control human subjects and three human subjects with SCD (D), and four control human subjects and four human subjects with SCD (E). #P < 0.05 when compared with LPS, *P < 0.05 when compared with baseline, and +P < 0.05 when compared with control. ICAM-1 = intercellular adhesion molecule-1; qMFM = quantitative microfluidic fluorescence microscopy; SCD = sickle cell disease.

Next, SCD and control human blood were treated with 0.25 and 1 μg/ml LPS, respectively. The effect of Mitotempo, as well as YVAD-CHO, on platelet–neutrophil aggregation was assessed using qMFM (see Figure 2A). Mitotempo significantly reduced the total number of platelet–neutrophil interactions (see Figure 2D) and the number of platelet interactions per neutrophil (see Figure E7C) in LPS-treated control and SCD human blood. YVAD-CHO significantly reduced the total platelet–neutrophil interactions in LPS-treated SCD human blood (see Figure 2E) and platelet interactions per neutrophil in both LPS-treated control and SCD human blood (see Figure E7D). Treatment with vehicle (DMSO) had no effect on platelet–neutrophil interactions (Figure E8).

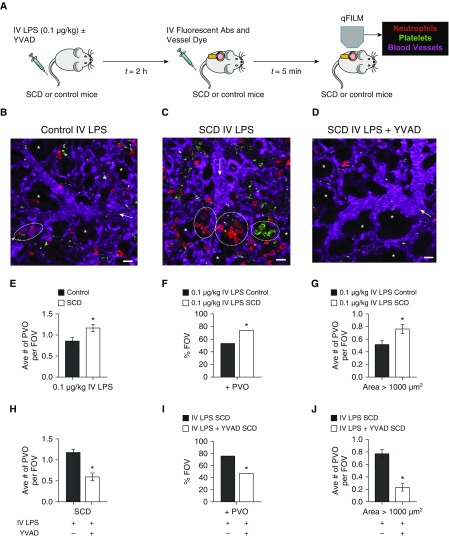

Inflammasome Inhibition Prevents Pulmonary Vasoocclusion in SCD Mice In Vivo

qFILM was used to determine the effect of caspase-1 inhibition on pulmonary vasoocclusion in SCD mice in vivo (Figure 3). As shown in Figure 3A, we used our recently validated model of pulmonary vasoocclusion in SCD mice (6), triggered by intravenous administration of 0.1 μg/kg LPS (∼2–3 ng per mouse). Identical to our previous report (6), intravenous LPS led to occlusion of vascular “bottlenecks” located between pulmonary arterioles and capillaries by large neutrophil–platelet aggregates, which were not only significantly more numerous but also significantly larger in SCD than control mice (see Figure 3B vs. 3C and Video E1 vs. E2). Figure 3C and Video E2 show three large aggregates of neutrophils and platelets sequestered in lung arterioles of an SCD mouse administered LPS. Pulmonary vasoocclusions were quantified as described previously (6) in multiple FOVs (∼15–20) per mouse with three to five mice in each treatment group. As shown in Figures 3E–3G, SCD mice given 0.1 μg/kg intravenous LPS had a significantly higher number of pulmonary vasoocclusions per FOV, the percentage of FOVs with pulmonary vasoocclusions, and number of large (area > 1,000 μm2) pulmonary vasoocclusions per FOV compared with control mice administered 0.1 μg/kg intravenous LPS. Mice administered intravenous saline had fewer and smaller pulmonary vasoocclusions (Figure E9). Remarkably, a majority of the FOVs were free of pulmonary vasoocclusions in SCD mice intravenously administered with 0.002 μmol/kg caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD-CHO before 0.1 μg/kg intravenous LPS. Figure 3D and Video E3 show a representative FOV of the lung microcirculation without any neutrophil–platelet aggregates in a SCD mouse intravenously administered with both YVAD-CHO and LPS. Video E3 shows freely circulating neutrophils trafficking through the arteriole into the capillaries, indicating the lack of vasoocclusion. Caspase-1 inhibition significantly reduced neutrophil–platelet aggregate formation and pulmonary vasoocclusions in SCD mice (see Figure 3H–3J). Although all three parameters were significantly reduced, the decrease in the large vasoocclusions (area > 1,000 μm2) was the most striking (see Figure 3J). Caspase-1 inhibition did not attenuate the small number of pulmonary vasoocclusions observed in control mice (Figure E10).

Figure 3.

Inflammasome inhibition prevents pulmonary vasoocclusion (PVO) in SCD mice in vivo. (A) Experimental scheme: Control and SCD mice were intravenously administered 0.1 μg/kg LPS ± 0.002 μmol/kg caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD, and qFILM was used to assess the absence or presence of platelet–neutrophil aggregate–mediated PVO. Representative fields of view (FOVs; ∼65,536 μm2) are shown in B–D. (B) Intravenous LPS led to minimal vasoocclusion in control mice (a small platelet–neutrophil aggregate blocking the arteriolar bottleneck marked by dotted circle). As shown in Video E1, circulating neutrophils still transit through the other unoccluded arteriolar branch, suggesting that fewer and smaller platelet–neutrophil aggregates in control mice minimally obstructed the pulmonary blood flow. (C) Intravenous LPS led to occlusion of arteriolar bottlenecks in the lung of SCD mice by large platelet–neutrophil aggregates (aggregates marked by dotted white circles). As seen in Video E2, the three neutrophil–platelet aggregates block the blood flow from the arteriolar branches into the capillaries, which is evident by the back-and-forth movement of cells in the main arteriole. (D) Caspase-1 inhibition abolished intravenous LPS-triggered platelet–neutrophil aggregation in the lungs of SCD mice, resulting in an absence of vasoocclusion from the majority of FOVs. The complete time series for B–D are shown in Videos E1–E3, respectively. Pulmonary microcirculation (pseudocolor purple), neutrophils (red), and platelets (pseudocolor green) were labeled in vivo by intravenous administration of fluorescein isothiocyanate dextran, AF546-Ly6G Ab, and V450-CD49b Ab, respectively. Alveoli are marked with asterisks. White arrows denote the direction of blood flow within the arterioles (scale bars, 20 μm). The diameters of the arterioles shown in B–D are 29, 31, and 40 μm, respectively. (E–J) PVOs were quantified as described in the online supplement. Intravenous LPS led to significantly (E) higher average number of PVOs per FOV, (F) higher percentage of FOVs with PVOs, and (G) more large PVOs with areas > 1,000 μm2 in SCD compared with control mice. Caspase-1 inhibition with YVAD significantly reduced (H) the average number of PVOs per FOV, (I) the percentage of FOVs with PVOs, and (J) large PVOs with area > 1,000 μm2 in SCD mice administered intravenous LPS with YVAD compared with SCD mice administered intravenous LPS only. The average number of PVOs per FOV and large PVOs (area > 1,000 μm2) were compared between groups using the unpaired Student’s t test, and the percentage of FOVs with PVOs were compared between groups using fourfold table analyses. Error bars are SE. The following were administered: intravenous LPS control (n = 5 mice; 113 FOVs); intravenous LPS SCD (n = 5 mice; 116 FOVs); and intravenous LPS with YVAD SCD (n = 3 mice; 64 FOVs). *P < 0.05. Abs = antibodies; IV = intravenous; qFILM = quantitative fluorescence intravital lung microscopy; SCD = sickle cell disease; YVAD = caspase-1 inhibitor.

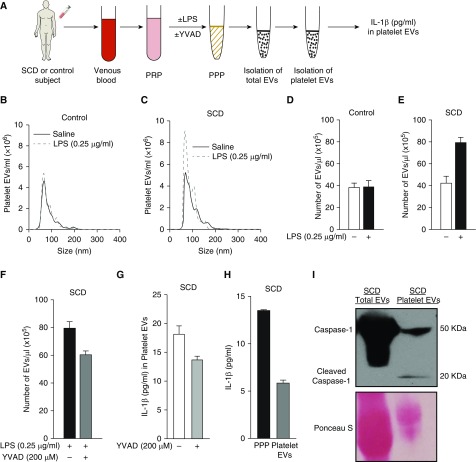

Inflammasome Promotes Generation of IL-1β–Carrying Platelet EVs in SCD

Platelet-rich plasma from control human subjects and human subjects with SCD were either left untreated or treated with 0.25 μg/ml LPS. Platelet-rich plasmas were processed to generate platelet-poor plasmas and the number of platelet-derived EVs were measured in platelet-poor plasmas (Figure 4A) using the strategy described in the online supplement. Because the disease severity is known to be heterogeneous among patients with SCD (1), EV analysis was done separately for each SCD human subject and reported as a mean of three repetitions per subject. The size distribution and concentration of platelet EVs was determined using nanoparticle tracking analysis. Representative size distribution histograms of platelet EVs isolated from a saline or LPS-treated control and SCD human platelet-rich plasma are shown in Figures 4B and 4C, respectively. Both control (see Figure 4B) and SCD (see Figure 4C) platelet EVs primarily ranged between 50 and 200 nm in size, and this size range was not affected by LPS treatment. Treatment with 0.25 μg/ml LPS did not result in generation of EVs by platelets of a control human subject (see Figure 4D). In contrast, 0.25 μg/ml LPS led to a twofold increase in generation of EVs by platelets of an SCD human subject (see Figure 4E), which was attenuated by pretreatment with 200 μM caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD-CHO (see Figure 4F). To validate our finding, we assessed the effect of caspase-1 inhibition on LPS-triggered (0.25 μg/ml) EV generation by platelets of a second SCD human subject and observed an identical reduction in platelet EV generation (Figure E11). Next, platelet-derived EVs were isolated and the IL-1β expression in these EVs was measured using ELISA (refer to the online supplement for details). As shown in Figure 4G (white bar), IL-1β was abundant in the platelet-derived EVs of the patient with SCD, and these values were comparable to reported IL-1β levels in the serum of patients with SCD (38). Due to the generation of fewer platelet EVs after caspase-1 inhibition (see Figures 4F and E11), inhibition of caspase-1 also led to reduced total IL-1β content in platelet EVs (see Figure 4G, gray bar). Next, platelet-rich plasmas from human subjects with SCD were treated with LPS (0.25 μg/ml) and processed to generate platelet-poor plasmas. Comparison of IL-1β content in an SCD human platelet-poor plasma with platelet EVs isolated from the same sample of platelet-poor plasma revealed that approximately 45% of IL-1β in plasma was platelet EV–bound (see Figure 4H, black vs. gray bar). A similar finding for a second SCD human subject is shown in Figure E12. Recently (39), caspase-1 was shown to be present in EVs isolated from plasma of patients with acute lung injury. Identical to these findings, Western blot analysis revealed the presence of caspase-1 (50 kD) in both total and platelet EVs (see Figures 4I and E13) and cleaved caspase-1 (20 kD) in platelet EVs (see Figures 4I, second lane, and E13) isolated from LPS-treated SCD human platelet-rich plasma.

Figure 4.

Inflammasome promotes generation of IL-1β and caspase-1–carrying platelet extracellular vesicles (EVs) in SCD. (A) Experimental scheme: Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was prepared from control and SCD human blood. PRPs were either left untreated or treated with 0.25 μg/ml LPS in the absence or presence of caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD (200 μM) and processed to generate platelet-poor plasma (PPP). PPPs were used for isolation and quantification of total and platelet-derived EVs. IL-1β content in platelet EVs was estimated using ELISA. Refer to the online supplement for details on EV isolation and quantification. Nanoparticle tracking analysis was used to estimate the size distribution and concentration of platelet EVs. Representative nanoparticle tracking analysis data are shown for platelet EVs isolated from saline (solid curve) or 0.25 μg/ml LPS-treated (dashed curve) PRP of (B) a control and (C) an SCD human subject. (D–F) Although incubation with 0.25 μg/ml LPS did not promote EV generation by platelets in control human PRP (D), it led to a twofold increase in EVs in SCD human PRP (E), which was reduced after treatment with YVAD (F). (G) IL-1β was present in platelet-derived EVs isolated from SCD human PRP, and the levels were reduced after pretreatment with YVAD. (H) SCD human PRP treated with 0.25 μg/ml LPS was processed to generate PPP. PPP was used for isolation of platelet-derived EVs. IL-1β content in PPP and platelet EVs isolated from same PPP was compared using ELISA and reported as picograms per milliliter of PPP. Approximately 50% of IL-1β in PPP was bound to platelet EVs. (I) SCD human PRP treated with LPS (0.25 μg/ml) was processed to isolate total and platelet-derived EVs using the method described in the online supplement. EVs were lysed and used in Western blot analysis to detect caspase-1 using polyclonal rabbit anti–human caspase-1 antibody (Clone #2225; Cell Signaling Tech). Western blot micrograph showing caspase-1 (50 kD) was present in both total and platelet EVs, and cleaved caspase-1 (20 kD) was detectable in platelet EVs. Ponceau S was used as the loading control. Complete gel is shown in Figure E13. Each bar in D–H represents mean ± SE of three repetitions. Data in B–I are representative of experiments done with blood samples of four human subjects with SCD and two control human subjects. SCD = sickle cell disease; YVAD = caspase-1 inhibitor.

Inhibition of IL-1β Pathway Prevents Lung Vasoocclusion in SCD Mice In Vivo

SCD and control mice were intravenously administered 0.1 μg/kg LPS with 1 or 5 mg/kg of recombinant human IL-1RA (Figure E14A), and neutrophil–platelet aggregation in the lung arterioles was assessed using qFILM. IL-1RA attenuated vasoocclusion in the lung arterioles of SCD mice in a dose-dependent manner. IL-1RA (1 mg/kg) led to a small but significant reduction in the average number of pulmonary vasoocclusions per FOV, the percentage of FOVs with pulmonary vasoocclusions, and the average number of large pulmonary vasoocclusions (area > 1,000 μm2) per FOV in SCD mice (see Figures E14B and E14D). Similar to the lack of effect of caspase-1 inhibitor in control mice (see Figure E10), IL-1RA did not affect the percentage of FOVs with pulmonary vasoocclusions and the average number of large pulmonary vasoocclusions (area > 1,000 μm2) per FOV in control mice (Figure E15). A majority of FOVs in SCD mice intravenously administered 5 mg/kg IL-1RA with 0.1 μg/kg LPS were free of neutrophil–platelet aggregates (Figure E16B and Video E4). qFILM analyses revealed a significantly large (50%) reduction in the average number of pulmonary vasoocclusions per FOV (see Figure E16C), the percentage of FOVs with pulmonary vasoocclusions (see Figure E16D), and average number of large pulmonary vasoocclusions (area > 1,000 μm2) per FOV (see Figure E16E) in SCD mice intravenously administered 5 mg/kg IL-1RA with 0.1 μg/kg LPS compared with SCD mice intravenously administered 0.1 μg/kg LPS only.

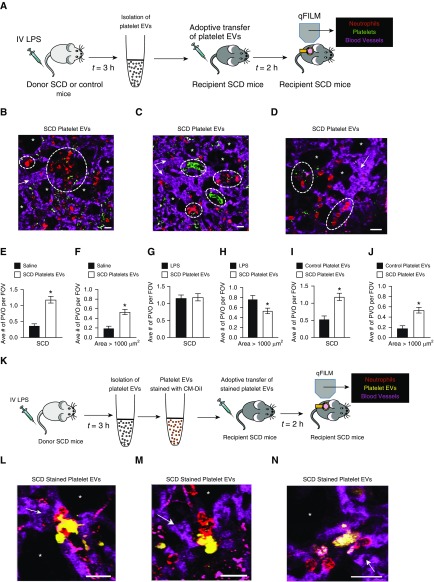

Platelet EVs Promote Lung Vasoocclusion in SCD Mice In Vivo

SCD or control mice were given 1 μg/kg intravenous LPS and platelet-derived EVs were harvested from the whole blood of these mice, as described in the online supplement (Figure 5A). Size distribution and concentration of EVs were determined using nanoparticle tracking analysis. Representative size distributions and total numbers of platelet EVs isolated from an LPS-challenged control and SCD mouse are shown in Figures E17A and E17B, respectively. Similar to human platelet EVs (see Figures 4B and 4C), both control and SCD mice platelet EVs ranged in size from 50 to 200 nm (see Figure E17). As depicted in Figure 5A, either half (∼5 × 108) or all the (∼109) platelet EVs isolated from a donor SCD mouse were intravenously administered into an unchallenged (no LPS administered) age-matched and weight-matched recipient SCD mouse, and pulmonary vasoocclusion was assessed using qFILM. Remarkably, SCD platelet EVs resulted in large neutrophil–platelet aggregates in the lung arterioles of recipient SCD mice (see Figures 5B–5D and Videos E5–E7). Figures 5B–5D and corresponding Videos E5–E7 show three separate FOVs with large aggregates of neutrophils and platelets (dotted white circles) blocking arteriolar bottlenecks in the lungs of SCD mice intravenously administered SCD platelet EVs. After intravenous administration of SCD platelet EVs in SCD mice, the average number of pulmonary vasoocclusions per FOV and pulmonary vasoocclusions with area > 1,000 μm2 were significantly higher compared with SCD mice administered saline (see Figures 5E and 5F). In contrast, the average number of pulmonary vasoocclusions per FOV was identical and the average number of pulmonary vasoocclusions with area > 1,000 μm2 was only slightly less in SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs than in SCD mice administered 0.1 μg/kg intravenous LPS (see Figures 5G and 5H). As depicted in Figure 5A, platelet EVs were also isolated from LPS-treated control mice and then intravenously administered to recipient SCD mice. qFILM revealed that a majority of FOVs in recipient SCD mice administered control platelet EVs were free of neutrophil–platelet aggregates (representative FOV shown in Video E8). Both the average number of pulmonary vasoocclusions per FOV (see Figure 5I) and pulmonary vasoocclusions with area > 1,000 μm2 (see Figure 5J) were approximately 60% (significantly) smaller in SCD mice administered control platelet EVs than in SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs. As depicted in Figure 5K, these qFILM experiments were repeated with SCD platelet EVs stained with CM-DiI. Figures 5L–5N and corresponding Videos E9–E11 show three separate FOVs that reveal SCD platelet EVs (yellow) bound to aggregates of neutrophils (red) occluding arteriolar bottlenecks in the lung of recipient SCD mice.

Figure 5.

Platelet extracellular vesicles (EVs) promote lung vasoocclusion in SCD mice in vivo. (A) Experimental scheme #1: Donor SCD or control mice were intravenously administered LPS (1 μg/kg); platelet EVs were isolated from the blood and adoptively (intravenously) transferred into unchallenged recipient SCD mice. Lung vasoocclusion was assessed in recipient mice using quantitative fluorescence intravital lung microscopy (qFILM) and compared with lung vasoocclusion in SCD mice administered intravenous LPS or saline. Refer to the online supplement for details. (B–D) Three representative qFILM images reveal large neutrophil–platelet aggregates (marked by dashed white circles) blocking arteriolar bottlenecks in the lung of recipient SCD mice intravenously administered SCD platelet EVs. Videos E5–E7 show the complete time series of fields of view (FOVs) shown in B–D. Intravenous administration of SCD platelet EVs caused a significant increase in the (E) average number of pulmonary vasoocclusions (PVOs) per FOV and (F) large PVOs (area > 1,000 μm2) per FOV in recipient SCD mice compared with intravenous saline. (G) The average number of PVOs per FOV was not different and (H) large PVOs (area > 1,000 μm2) per FOV were slightly reduced in recipient SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs compared with SCD mice administered 0.1 μg/kg LPS. Both (I) the average number of PVOs per FOV and (J) large PVOs (area > 1,000 μm2) per FOV were significantly greater in recipient SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs compared with recipient SCD mice administered control platelet EVs. The following were administered: saline (n = 5 mice; 81 FOVs), 0.1 μg/kg LPS (n = 5 mice; 116 FOVs), SCD platelet EVs (n = 6 mice; 87 FOVs), and control platelet EVs (n = 4 mice; 51 FOVs). The average number of PVOs per FOV and large PVOs (area > 1,000 μm2) per FOV were compared between groups using the unpaired Student’s t test. Error bars are SE. Pulmonary microcirculation (pseudocolor purple), neutrophils (red), and platelets (pseudocolor green) are shown. The diameters of the arterioles in B–D are 37, 38, and 33 μm, respectively. (K) Experimental scheme #2: Experiments described in scheme #1 were repeated with SCD platelet EVs stained with chloromethyl-dialkylcarbocyanine (CM-DiI). (L–N) Three representative qFILM images show SCD platelet EVs (yellow) bound to neutrophil aggregates (red) in the lung arterioles (purple) of recipient SCD mice intravenously administered CM-DiI-stained SCD platelet EVs. Videos E9–E11 show the complete time series of FOVs shown in L–N, respectively. Platelet staining with V450-CD49b Ab was skipped in these experiments and, therefore, platelets are not visible in L–N and Videos E9–E11. Pulmonary microcirculation (fluorescein isothiocyanate dextran, pseudocolor purple), neutrophils (Pacific Blue Ly6G Ab, pseudocolor red), and platelet EVs (CM-DiI, pseudocolor yellow) are shown. Alveoli are marked with asterisks. The white arrows denote the direction of blood flow (scale bars, 20 μm). *P < 0.05. IV = intravenous; SCD = sickle cell disease.

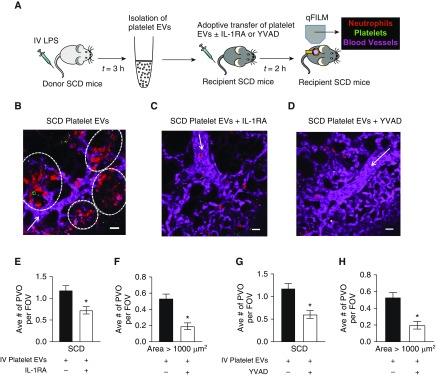

Platelet EV-induced Lung Vasoocclusion Is IL-1β Dependent and Caspase-1 Dependent

Donor SCD mice were intravenously administered 1 μg/kg LPS, platelet-derived EVs were harvested from the whole blood and intravenously administered to unchallenged recipient SCD mice with or without 10 mg/kg IL-1RA or 0.004 μmol/kg caspase-1 inhibitor (YVAD-CHO), and pulmonary vasoocclusion was assessed using qFILM (Figure 6A). Intravenous administration of SCD platelet EVs led to occlusion of pulmonary arteriolar bottlenecks in recipient SCD mice by large neutrophil–platelet aggregates (see Figure 6B), which were absent from a majority of FOVs in recipient SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs with IL-1RA (see Figure 6C) or YVAD-CHO (see Figure 6D). Refer to Videos E12–E14 for the complete time series corresponding to FOVs shown in Figures 6B–6D, respectively. Video E12 shows four large aggregates of neutrophils and platelets sequestered in lung arterioles of an SCD mouse administered SCD platelet EVs. In contrast, Videos E13 and E14 show freely circulating neutrophils trafficking down the arteriole into the capillaries, indicating the lack of lung vasoocclusion in SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs with IL-1RA or YVAD-CHO, respectively. The average number of pulmonary vasoocclusions per FOV (see Figure 6E) and pulmonary vasoocclusions with area > 1,000 μm2 (see Figure 6F) were significantly reduced by approximately 50% and 60%, respectively, in SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs with IL-1RA compared with SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs only. Both the average number of pulmonary vasoocclusions per FOV (see Figure 6G) and pulmonary vasoocclusions with area > 1,000 μm2 (see Figure 6H) were significantly reduced by approximately 60% in SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs with YVAD-CHO compared with SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs only.

Figure 6.

Platelet extracellular vesicle (EV)-induced lung vasoocclusion is IL-1β and caspase-1 dependent. (A) Experimental scheme: Donor SCD mice were intravenously administered LPS (1 μg/kg); platelet EVs were isolated from the blood and adoptively (intravenously) transferred into unchallenged recipient SCD mice without (n = 6 mice; 87 fields of view [FOVs]) or with (n = 5 mice; 76 FOVs) 10 mg/kg IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), or 0.004 μmol/kg caspase-1 inhibitor YVAD (n = 5 mice; 68 FOVs). Lung vasoocclusion was assessed in recipient mice using qFILM. Refer to the online supplement for details. Representative qFILM images reveal (B) presence of large neutrophil–platelet aggregates (marked by dashed white circles) blocking arteriolar bottlenecks in the lung of a recipient SCD mouse intravenously administered SCD platelet EVs and (C and D) absence of platelet–neutrophil aggregates in the lung of a recipient SCD mouse intravenously administered SCD platelet EVs with IL-1RA or SCD platelet EVs with YVAD. Videos E12–E14 show the complete time series of FOVs shown in B–D, respectively. (E) The average number of pulmonary vasoocclusions (PVOs) per FOV and (F) large PVOs (area > 1,000 μm2) per FOV were significantly reduced in recipient SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs with IL-1RA compared with recipient SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs only. (G) The average number of PVOs per FOV and (H) large PVOs (area > 1,000 μm2) per FOV were significantly reduced in recipient SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs with YVAD compared with recipient SCD mice administered SCD platelet EVs only. The average number of PVOs per FOV and large PVOs (area > 1,000 μm2) per FOV were compared between groups using the unpaired Student’s t test. Error bars are SE. Pulmonary microcirculation (pseudocolor purple), neutrophils (red) and platelets (pseudocolor green) are shown. The white arrows denote the direction of blood flow. The diameters of the arterioles in B–D are 22, 31, and 35 μm, respectively. Scale bars, 20 μm. *P < 0.05. IV = intravenous; qFILM = quantitative fluorescence intravital lung microscopy; SCD = sickle cell disease.

Discussion

Here, we use intravital microscopy (qFILM) of the lung in live mice and in vitro microfluidic studies (qMFM) with human blood to reveal that the inflammatory milieu in SCD promotes TLR4-dependent activation of the platelet NLRP3-inflammasome. Using confocal microscopy, we discovered that the NLRP3-ASC caspase-1 inflammasome complex was active in SCD but not control human platelets. Inhibition of the NLRP3-inflammasome pathway by scavenging mtROS or inhibiting caspase-1 completely abolished platelet–neutrophil aggregation in SCD human blood in vitro and prevented pulmonary vasoocclusion in SCD mice in vivo.

Platelets of patients with SCD contain significantly more IL-1β mRNA and secrete a significantly larger amount of IL-1β compared with control human platelets (40). Interestingly, platelet-derived EVs are among the most abundant species of EVs in SCD human blood and their numbers correlate with disease severity (41–43), but the role of platelet EVs in SCD pathophysiology remains unknown. Treatment with 0.25 μg/ml LPS selectively triggered the generation of IL-1β–carrying EVs by SCD but not control human platelets, which were attenuated after caspase-1 inhibition. We hypothesized that IL-1β–carrying platelet EVs may promote platelet–neutrophil aggregation–mediated lung vasoocclusion in SCD by activating the IL-1 receptor signaling in neutrophils, platelets, and other vascular cells. Indeed, intravenous administration of SCD but not control platelet EVs promoted pulmonary vasoocclusion in SCD mice in vivo, which involved binding of platelet EVs to neutrophils, leading to neutrophil–platelet aggregation. The inhibition of the IL-1β innate immune pathway by IL-1RA abolished both intravenous LPS and platelet EV–adoptive transfer-induced pulmonary vasoocclusion in SCD mice in vivo. In addition to IL-1β, SCD platelet EVs also carried cleaved caspase-1 and inhibition of caspase-1 also prevented platelet EV–adoptive transfer-induced pulmonary vasoocclusion in SCD mice in vivo. Taken together, our previous (6) and current findings (Figure E18) suggest that the inflammatory milieu (DAMPs) in SCD promotes TLR4-dependent activation of the NLRP3-inflammasome in platelets, which is enhanced by the presence of nanogram levels of a TLR4 ligand (pathogen-associated molecular pattern molecules), such as LPS. Inflammasome activation promotes the shedding of IL-1β and caspase-1–carrying EVs by activated platelets. Platelet EVs contribute to lung vasoocclusion by promoting caspase-1 and IL-1β–dependent activation of neutrophils and platelets to form large aggregates, which occlude pulmonary arterioles in SCD. The interpretation of our results is associated with a few limitations, which require further investigation in future studies. First, the NLRP3-inflammasome is the only inflammasome complex reported to promote platelet-mediated immune responses (35); however, other inflammasome complexes (44) or inflammasome-independent pathways might also contribute. Second, IL-1β–carrying platelet EVs may activate the IL-1 receptor on platelets by an autocrine loop (35, 45) to further promote generation of platelet EVs (see Figure E18, gray curved arrow). Third, activated platelets trapped within the platelet–neutrophil aggregates may undergo degranulation (46) to locally generate IL-1β–carrying EVs (see Figure E18, gray dotted arrow). Fourth, IL-1β–carrying platelet EVs may also activate the vascular endothelium (34). Fifth, mechanisms other than platelet EV generation may also contribute to pulmonary vasoocclusion and development of acute chest syndrome.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our findings highlight the potential of a novel antiinflammatory therapy for SCD, beyond the only two U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved drugs, hydroxyurea and L-glutamine (47–50). Our current data reveals that platelet–neutrophil aggregation in SCD is downstream to NLRP3-inflammasome–dependent caspase-1 activation in platelets, and IL-1β–mediated activation of neutrophils, platelets, and other vascular cells. These findings also imply that therapeutic inhibition of the NLRP3, caspase-1, and IL-1β innate immune pathway can be a promising therapeutic target for patients with SCD, particularly to halt the progression of acute chest syndrome in high-risk patients presenting with painful vasoocclusive crisis. Interestingly, IL-1RA (anakinra) and IL-1β–blocking Ab (canakinumab) are already U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved as antiinflammatory drugs for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (51) and cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome (52), respectively. Our current findings justify the need for clinical trials to test the safety and efficacy of repurposing these drugs in SCD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Yoel Sadovsky at Magee-Womens Research Institute, Pittsburgh, PA, for suggestions regarding EV characterization using nanoparticle tracking analysis. The authors would like to thank Joseph S. Bednash and Nathaniel Weathington at the University of Pittsburgh for suggestions regarding Western blot analysis of inflammasome components.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH-NHLBI grants 1R01HL128297 and 1R01HL141080, American Heart Association grants 18TPA34170588 and 11SDG7340005, and funds from the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania and Vitalant (P.S.); NIGMS 1R35GM119526 (M.D.N.); NIH-NHLBI training grant T32HL110849 and National Research Service Award grant 1F32HL131216-01 (M.F.B.); NIH-NHLBI training grant T32HL076124 and the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (M.A.J.); Postdoctoral Scholar Award from the American Society of Hematology (T.B.); Community Liver alliance award and PLRC pilot and feasibility grant (T.P.-S.); NIGMS R01GM102146 (M.J.S.); NHLBI 1R01HL133003 (S.S.); and American Heart Association award 19PRE34430188 (R.V.). The Nikon multiphoton excitation microscope was funded by NIH grant 1S10RR028478-01 (S.C.W.).

Author Contributions: R.V. and M.F.B. performed in vivo quantitative fluorescence intravital lung microscopy experiments with mice. T.B. isolated and analyzed platelet extracellular vesicles from mice and human blood, and performed ELISAs. M.A.J. performed quantitative microfluidic fluorescence microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and confocal and Western blots with human blood. R.V. performed confocal image analysis. T.P.-S. performed Western blots on extracellular vesicles and platelets. E.T. performed cluster of differentiation 14 Western blots and genotyped the sickle cell disease mice. J.J. and G.J.K. provided blood samples from human subjects. M.J.S., A.E.M., and M.D.N. were involved in characterization of extracellular vesicles. S.S. was involved in experiments with Mitotempo. E.G. was involved in designing the microfluidic device. S.C.W. was involved in quantitative fluorescence intravital lung microscopy experiments. M.T.G. was involved in experimental design and manuscript writing. P.S. was responsible for experimental design, manuscript writing, and project supervision. P.S. wrote the manuscript with contribution from all coauthors.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201807-1370OC on September 9, 2019

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Rees DC, Williams TN, Gladwin MT. Sickle-cell disease. Lancet. 2010;376:2018–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61029-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mortality GBD GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117–171. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frenette PS, Atweh GF. Sickle cell disease: old discoveries, new concepts, and future promise. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:850–858. doi: 10.1172/JCI30920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller AC, Gladwin MT. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:1154–1165. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2082CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaturvedi S, Ghafuri DL, Glassberg J, Kassim AA, Rodeghier M, DeBaun MR. Rapidly progressive acute chest syndrome in individuals with sickle cell anemia: a distinct acute chest syndrome phenotype. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:1185–1190. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennewitz MF, Jimenez MA, Vats R, Tutuncuoglu E, Jonassaint J, Kato GJ, et al. Lung vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease mediated by arteriolar neutrophil-platelet microemboli. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e89761. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anea CB, Lyon M, Lee IA, Gonzales JN, Adeyemi A, Falls G, et al. Pulmonary platelet thrombi and vascular pathology in acute chest syndrome in patients with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:173–178. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gladwin MT, Ofori-Acquah SF. Erythroid DAMPs drive inflammation in SCD. Blood. 2014;123:3689–3690. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-563874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sundd P, Gladwin MT, Novelli EM. Pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019;14:263–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato GJ, Steinberg MH, Gladwin MT. Intravascular hemolysis and the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:750–760. doi: 10.1172/JCI89741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vichinsky EP, Neumayr LD, Earles AN, Williams R, Lennette ET, Dean D, et al. National Acute Chest Syndrome Study Group. Causes and outcomes of the acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1855–1865. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006223422502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gladwin MT, Vichinsky E. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2254–2265. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strouse JJ, Reller ME, Bundy DG, Amoako M, Cancio M, Han RN, et al. Severe pandemic H1N1 and seasonal influenza in children and young adults with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2010;116:3431–3434. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-282194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cardenes N, Corey C, Geary L, Jain S, Zharikov S, Barge S, et al. Platelet bioenergetic screen in sickle cell patients reveals mitochondrial complex V inhibition, which contributes to platelet activation. Blood. 2014;123:2864–2872. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-529420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villagra J, Shiva S, Hunter LA, Machado RF, Gladwin MT, Kato GJ. Platelet activation in patients with sickle disease, hemolysis-associated pulmonary hypertension, and nitric oxide scavenging by cell-free hemoglobin. Blood. 2007;110:2166–2172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-061697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wun T, Paglieroni T, Rangaswami A, Franklin PH, Welborn J, Cheung A, et al. Platelet activation in patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 1998;100:741–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inwald DP, Kirkham FJ, Peters MJ, Lane R, Wade A, Evans JP, et al. Platelet and leucocyte activation in childhood sickle cell disease: association with nocturnal hypoxaemia. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:474–481. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polanowska-Grabowska R, Wallace K, Field JJ, Chen L, Marshall MA, Figler R, et al. P-selectin-mediated platelet-neutrophil aggregate formation activates neutrophils in mouse and human sickle cell disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:2392–2399. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.211615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wun T, Cordoba M, Rangaswami A, Cheung AW, Paglieroni T. Activated monocytes and platelet-monocyte aggregates in patients with sickle cell disease. Clin Lab Haematol. 2002;24:81–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2257.2002.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang D, Chen G, Manwani D, Mortha A, Xu C, Faith JJ, et al. Neutrophil ageing is regulated by the microbiome. Nature. 2015;525:528–532. doi: 10.1038/nature15367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennewitz MF, Watkins SC, Sundd P. Quantitative intravital two-photon excitation microscopy reveals absence of pulmonary vaso-occlusion in unchallenged Sickle Cell Disease mice. Intravital. 2014;3:e29748. doi: 10.4161/intv.29748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jimenez MA, Tutuncuoglu E, Barge S, Novelli EM, Sundd P. Quantitative microfluidic fluorescence microscopy to study vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease. Haematologica. 2015;100:e390–e393. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.126631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sundd P, Jimenez M, Bennewitz M, Brzoska T, Gladwin MT. Platelets shed extracellular vesicles to promote IL-1 beta dependent lung vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:A2700. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sundd P, Jimenez MA, Bennewitz MF, Brzoska T, Tutuncuoglu E, Kato GJ, et al. Hairy platelet-derived extracellular vesicles promote lung vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease Blood 201713095828838938 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jimenez MA, Novelli E, Shaw GD, Sundd P. Glycoprotein Ibα inhibitor (CCP-224) prevents neutrophil-platelet aggregation in sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2017;1:1712–1716. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017006742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Damiano ER, Westheider J, Tözeren A, Ley K. Variation in the velocity, deformation, and adhesion energy density of leukocytes rolling within venules. Circ Res. 1996;79:1122–1130. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.6.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sundd P, Pospieszalska MK, Cheung LS, Konstantopoulos K, Ley K. Biomechanics of leukocyte rolling. Biorheology. 2011;48:1–35. doi: 10.3233/BIR-2011-0579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu LC, Sun CW, Ryan TM, Pawlik KM, Ren J, Townes TM. Correction of sickle cell disease by homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Blood. 2006;108:1183–1188. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh S, Adisa OA, Chappa P, Tan F, Jackson KA, Archer DR, et al. Extracellular hemin crisis triggers acute chest syndrome in sickle mice. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4809–4820. doi: 10.1172/JCI64578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belcher JD, Chen C, Nguyen J, Milbauer L, Abdulla F, Alayash AI, et al. Heme triggers TLR4 signaling leading to endothelial cell activation and vaso-occlusion in murine sickle cell disease. Blood. 2014;123:377–390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berkson J. Limitations of the application of fourfold table analysis to hospital data. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:511–515. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sachs L. Applied statistics: a handbook of techniques. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elliott EI, Sutterwala FS. Initiation and perpetuation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and assembly. Immunol Rev. 2015;265:35–52. doi: 10.1111/imr.12286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hottz ED, Lopes JF, Freitas C, Valls-de-Souza R, Oliveira MF, Bozza MT, et al. Platelets mediate increased endothelium permeability in dengue through NLRP3-inflammasome activation. Blood. 2013;122:3405–3414. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-504449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hottz ED, Monteiro AP, Bozza FA, Bozza PT. Inflammasome in platelets: allying coagulation and inflammation in infectious and sterile diseases? Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:435783. doi: 10.1155/2015/435783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Rathinam VA, Lee SJ, Dolinay T, Lam HC, et al. Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:222–230. doi: 10.1038/ni.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sokolovska A, Becker CE, Ip WK, Rathinam VA, Brudner M, Paquette N, et al. Activation of caspase-1 by the NLRP3 inflammasome regulates the NADPH oxidase NOX2 to control phagosome function. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:543–553. doi: 10.1038/ni.2595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alagbe AE, Justo Junior AS, Ruas LP, Tonassé WV, Santana RM, Batista THC, et al. Interleukin-27 and interleukin-37 are elevated in sickle cell anemia patients and inhibit in vitro secretion of interleukin-8 in neutrophils and monocytes. Cytokine. 2018;107:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitra S, Exline M, Habyarimana F, Gavrilin MA, Baker PJ, Masters SL, et al. Microparticulate caspase 1 regulates gasdermin D and pulmonary vascular endothelial cell injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;59:56–64. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0393OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davila J, Manwani D, Vasovic L, Avanzi M, Uehlinger J, Ireland K, et al. A novel inflammatory role for platelets in sickle cell disease. Platelets. 2015;26:726–729. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2014.983891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tantawy AA, Adly AA, Ismail EA, Habeeb NM, Farouk A. Circulating platelet and erythrocyte microparticles in young children and adolescents with sickle cell disease: relation to cardiovascular complications. Platelets. 2013;24:605–614. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2012.749397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomer A, Harker LA, Kasey S, Eckman JR. Thrombogenesis in sickle cell disease. J Lab Clin Med. 2001;137:398–407. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2001.115450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zahran AM, Elsayh KI, Saad K, Embaby MM, Youssef MAM, Abdel-Raheem YF, et al. Circulating microparticles in children with sickle cell anemia in a tertiary center in upper Egypt. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2019;25:1076029619828839. doi: 10.1177/1076029619828839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Man SM, Kanneganti TD. Regulation of inflammasome activation. Immunol Rev. 2015;265:6–21. doi: 10.1111/imr.12296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown GT, Narayanan P, Li W, Silverstein RL, McIntyre TM. Lipopolysaccharide stimulates platelets through an IL-1β autocrine loop. J Immunol. 2013;191:5196–5203. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eckly A, Rinckel JY, Proamer F, Ulas N, Joshi S, Whiteheart SW, et al. Respective contributions of single and compound granule fusion to secretion by activated platelets. Blood. 2016;128:2538–2549. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-03-705681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Telen MJ. Beyond hydroxyurea: new and old drugs in the pipeline for sickle cell disease. Blood. 2016;127:810–819. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-618553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kato GJ, Piel FB, Reid CD, Gaston MH, Ohene-Frempong K, Krishnamurti L, et al. Sickle cell disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18010. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Novelli EM, Gladwin MT. Crises in sickle cell disease. Chest. 2016;149:1082–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manwani D, Frenette PS. Vaso-occlusion in sickle cell disease: pathophysiology and novel targeted therapies. Blood. 2013;122:3892–3898. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-498311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fleischmann RM, Tesser J, Schiff MH, Schechtman J, Burmester GR, Bennett R, et al. Safety of extended treatment with anakinra in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1006–1012. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.048371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lachmann HJ, Kone-Paut I, Kuemmerle-Deschner JB, Leslie KS, Hachulla E, Quartier P, et al. Canakinumab in CAPS Study Group. Use of canakinumab in the cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2416–2425. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.