Abstract

Few patients with opioid use disorder receive medication for addiction treatment. In 2017, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act enabled nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) to obtain federal waivers that allowed them to prescribe buprenorphine, a key medication for opioid use disorder. The waiver expansion was intended to increase patient access to opioid use treatment, which was particularly important for rural areas with few physicians. However, little is known about adoption of these waivers by NPs or PAs in rural areas. Using federal data, we examined waiver adoption in rural areas and its association with scope of practice regulations, which set the extent to which NPs or PAs can prescribe medication. From 2016 to 2019, the number of waivered clinicians per 100,000 population in rural areas increased by 111 percent. NPs and PAs accounted for more than half of this increase and were the first waivered clinicians in 285 rural counties with 5.7 million residents. In rural areas, broad scope of practice regulations were associated with twice as many waivered NPs per 100,000 population as restricted scopes of practice were. The rapid growth in the numbers of NPs and PAs with buprenorphine waivers is a promising development in improving access to addiction treatment in rural areas.

Nearly 48,000 Americans died as a result of opioid overdoses in 2017.1 Despite the magnitude of this crisis, only 10–25 percent of people with opioid use disorders (OUDs) receive treatment annually.2,3 Only about 34 percent of those who receive some treatment for OUD receive an evidence-based intervention—including buprenorphine-naloxone (hereafter, buprenorphine) and methadone—proven to improve abstinence and mortality.2,3 There are a variety of reasons for this failure to help people affected by the opioid epidemic. One central concern that is being addressed in policy is the limited availability of evidence-based care. Federal and state policy makers are recognizing the urgent need to adopt measures to reform the national infrastructure for OUD treatment.

Outpatient treatment of OUD with buprenorphine has the potential to rapidly reduce these barriers to accessing care.3,4 Buprenorphine is highly effective at reducing rates of overdose and significantly improves the likelihood of successful long-term recovery from OUD.5,6 Unlike methadone, which has strict federal regulations on its distribution, buprenorphine can be prescribed as an outpatient medication that people can take on their own without the need to travel to a facility for treatment. However, clinicians can prescribe buprenorphine only after obtaining a federal waiver that requires hours of formal training.7 And until 2017, physicians were the only clinicians permitted to obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for addiction treatment. The training requirement, along with other practical and cultural barriers, has limited the supply of providers authorized to treat OUD with buprenorphine.4,8

Barriers to accessing buprenorphine are magnified in rural areas, whose burden of opioid-related mortality is similar to that of more populous areas but that have a smaller health care workforce and fewer clinical resources. In 2017, 56 percent of rural counties had no clinician with a buprenorphine waiver, and among counties with a waivered clinician, evidence shows that up to half of clinicians may not accept new patients.9–11 An additional challenge is a shrinking workforce of primary care physicians in rural areas.12 However, as primary care physicians have been leaving rural counties, primary care nurse practitioners (NPs) have been replacing them.12 The growth of NPs in the rural primary care workforce offers the potential to help improve access to buprenorphine treatment, but until recently all advanced practice providers such as NPs and physician assistants (PAs) were barred from obtaining buprenorphine waivers.

The enactment of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act in 2016 enabled NPs and PAs to obtain buprenorphine waivers beginning in 2017.13 The act’s provisions aimed to expand access to OUD treatment, which could particularly impact rural areas that have few physicians.14 However, even with a federal buprenorphine waiver, the ability of NPs and PAs to prescribe controlled substances is determined by state-level scope of practice regulations. These regulations establish the extent to which NPs or PAs can clinically practice or prescribe medication without a collaborative or supervisory agreement with a physician. If a state’s scope of practice laws require physician supervision for an NP or PA to prescribe medication, then buprenorphine is unlikely to be prescribed unless both the supervising physician and the NP or PA have waivers. Scope of practice policies vary considerably across states and are a source of controversy.15–17 Restrictive scope of practice regulations may significantly limit NP and PA capacity to prescribe buprenorphine in states with a high proportion of rural residents, such as West Virginia and Tennessee.18,19

The burden of the opioid epidemic in rural areas adds new public health considerations to the debate around scope of practice regulations. A recent analysis shows that more restrictive regulations were associated with lower adoption of buprenorphine waivers by advanced practice providers.20 That analysis was based on cross-sectional state-level data, and there is still little evidence on the magnitude of buprenorphine waiver adoption by NPs and PAs in rural counties and whether adoption was associated with scope of practice regulation. This article seeks to offer a more complete view of the impact of state scope of practice regulations on the availability of waivered providers of treatment. We pursued this issue by using a comprehensive database of all buprenorphine waivers granted nationally to examine county-level patterns of waiver adoption by advanced practice providers and their association with scope of practice regulations.

Study Data And Methods

Data Sources And Study Sample

Our analysis relied on a database of all clinicians with buprenorphine waivers from the inception of the program in 2002 through March 31, 2019 (that is, the first quarter of 2019). These data were obtained from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) through a Freedom of Information Act request (SAMHSA Case No. 04042019S123). The data set contains the date of each clinician’s waiver approval, the date of any waiver that expanded patient capacity beyond the default (a waiver for thirty patients), total waiver patient capacity (30, 100, or 275 patients), and the county of practice for all publicly listed and unlisted clinicians with waivers—physicians, NPs, and PAs—in the study period. We included all clinicians in the data set with a nonmissing office location (1,327 clinicians, or 2 percent of the total, had no address or ZIP code in the data). We aggregated the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration waiver database to the quarterly level for 2016–19 for 3,147 counties or county-equivalents in all fifty states and the District of Columbia.

To supplement the information in the database, we used the Area Health Resources Files for county-level characteristics, including population, socioeconomic indicators, proportion living in urban areas, and racial/ethnic distributions.21 We also obtained 2016 opioid overdose mortality data at the county level from the Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) database of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).22 Finally, we used the 2013 urban-rural classification of the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics to categorize counties into three groups: rural (defined as micropolitan or noncore counties with a population of less than 50,000), small to medium metro (defined as counties in Metropolitan Statistical Areas with a population of more than 50,000 and less than 1,000,000), and large metro (counties with a population of more than 1,000,000).23

The Comprehensive Addiction And Recovery Act And Scope Of Practice Regulations

Our focus was on the impact of state scope of practice regulations on the implementation of the change in the eligibility of NPs and PAs to receive buprenorphine waivers under the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act. Beginning on January 1, 2017, the act enabled NPs and PAs to obtain federal waivers to prescribe buprenorphine for up to thirty patients after twenty-four hours of training (in comparison, physicians require only eight hours of training to obtain a waiver). Like physicians, NPs and PAs are also able to raise their waivered patient limit to 100 after one year of prescribing with a 30-patient limit, but unlike physicians, they are not eligible to receive a 275-patient waiver. Because of this one-year requirement, by definition no NPs or PAs were able to obtain 100-patient waiver expansions before January 1, 2018.

To measure scope of practice regulations for NPs, we classified states according to their 2016 scope of practice laws, as previously defined by Hilary Barnes and coauthors,24 into two categories: states with “full” and those with “restricted” scopes of practice. States with full NP scope of practice were defined as those in which NPs had full autonomy to practice clinically and prescribe independently, without a requirement for a collaborative agreement or postlicensure supervision. Restricted or reduced scope of practice included all other states where a collaborative agreement was necessary for prescribing authority (reduced) or both prescribing authority and clinical practice (restricted). We compared states with full NP scope of practice versus all other states as our main analysis. We defined states with full PA scope of practice as those with regulations that satisfied the six key elements of practice defined by the American Academy of PAs,25 and we defined states with restricted scope of practice as those whose regulations satisfied five or fewer of these elements.26 The full list of scope of practice state classifications is available in online appendix exhibit 1.27

Buprenorphine Waiver Outcomes

Measured each month after January 2017, our primary county-level outcomes of interest were total “buprenorphine treatment capacity” (defined as the number of patients potentially treatable with buprenorphine by all clinicians with waivers to prescribe the medication in a county) per 100,000 population, the number of NPs and PAs with buprenorphine waivers per 100,000 population, and the percentage of NPs and PAs in a county with buprenorphine waivers after implementation of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act. In addition to examining buprenorphine treatment capacity for all clinicians (physicians, NPs and PAs) we also quantified treatment capacity for subsets of these providers (e.g. NPs alone and PAs alone). We additionally assessed which counties had no clinicians with buprenorphine waivers in the last quarter of 2016 (before implementation) and how many of these counties had acquired a waivered NP or PA by March 2019.

State And County Characteristics

We captured states’ expansion of eligibility for Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act as of 2016.28 We also gathered data for fiscal year 2016 on federal Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment block grants for all fifty states and Washington DC and calculated the block grant funding per 1,000 population in 2016 as a measure of federal investment in substance use disorder treatment.29

From the Area Health Resources Files and the CDC WONDER database, we measured the following characteristics for all counties, using the data closest in time to 2016 but not later than were available in the Area Health Resource Files: population; numbers of physicians, NPs, and PAs per capita; median age; proportion of people with less than a high school education; median household income; unemployment rate; proportions of the population younger than age sixty-five with no health insurance, disabled, in deep poverty (defined as a household with a total cash income below 50 percent of its poverty threshold), of white or black race, and of Hispanic ethnicity; and opioid-related mortality per capita. Further details on these county-level variables are available in appendix exhibit 2.27

Statistical Analysis

For all urban and rural counties, we captured the number and total population of counties with no buprenorphine provider at the end of 2016 (before implementation of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act) and then assessed how many of these counties had acquired an NP or PA with a buprenorphine waiver by March 2019. We also assessed the average county-level change in buprenorphine treatment capacity and the number of waivered clinicians from the last quarter of 2016 through the first quarter of 2019.

We compared the characteristics of rural counties with any versus no waivered NP or PA as of March 2019, as well as the characteristics of rural counties with any waivered NPs or PAs, stratified into quartiles of waivered NPs and PAs per 100,000 population as of March 2019. We used county-level linear regression, controlling for the county demographics listed above, to estimate adjusted differences in characteristics between rural counties with and those without waivered NPs or PAs and between counties in the highest and those in the lowest quartiles of waivered NPs and PAs per capita.

Finally, we compared the average county-level buprenorphine treatment capacity from all clinicians, from physicians alone, and from NPs and PAs alone and the number of waivered clinicians as of March 2019 in counties with full and those in counties with restricted scope of practice laws for NPs and PAs. To estimate the adjusted difference in these outcomes between counties by scope of practice, we used county-level linear regression, adjusting for all of the county demographics listed in appendix table 3 and the number of total physicians per 100,000 population.27 We also examined within-county monthly growth of waiver adoption as measured by buprenorphine treatment capacity from NPs and PAs by scope of practice, using a county-month-level linear regression model with county-level fixed effects. We used robust standard errors clustered at the state level.

Analyses were performed in R, version 3.5.0, and Stata, version 14.2. This study was deemed exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at the Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

Limitations

This analysis had several limitations. First, we were unable to assess the association of NP and PA waiver adoption with patient access to treatment because we lacked data on the prescribing of buprenorphine or other patient-level measures of medication-assisted therapy. It has been well documented that only a fraction of the clinicians who obtain a buprenorphine waiver prescribe any buprenorphine, and of those who do prescribe the medication, most are not prescribing at close to their waiver limit.11,30 Therefore, our analysis was focused on the clinicians who could deliver OUD treatment, not the direct measurement of access to those services.

Second, there were differences between states with and those without full scope of practice, so our analysis could not fully exclude the possibility that the states with full scope of practice would have had similar changes in the absence of those scope of practice regulations. Therefore, we could not assess the causal impact of scope of practice on buprenorphine waiver adoption. However, this analysis was able to assess the causal impact of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act on NP and PA waiver adoption nationally because before the act, there was no mechanism for NPs or PAs to acquire these waivers.

Third, there is no consensus on what “full” and “restricted” scope of practice means for NPs and PAs, and not all studies use the same definitions. Therefore, our results may differ depending on the criteria used to define full scope of practice.

Study Results

Nurse Practitioner and Physician Assistant Adoption Of Buprenorphine Waivers In Rural And Urban Counties

By the end of March 2019, 12,706 NPs and PAs in 1,401 counties had obtained buprenorphine waivers. In rural counties, total buprenorphine treatment capacity (the sum of the capacity of physicians, NPs, and PAs) had increased from December 2016 by 429 per 100,000 (a 90 percent relative increase), while the number of all waivered clinicians per 100,000 had increased by 7.2 (a 111 percent relative increase) (exhibit 1). The majority of the increase in waivered clinicians in rural counties from December 2016 to March 2019 came from NPs and PAs (4.0 clinicians per 100,000, or 56 percent of the 7.2 total increase).

Exhibit 1:

County-level buprenorphine waivered clinician availability in December 2016 and March 2019, by urban-rural classification

| County classification | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large metro | Small to medium metro | Rural | ||||

| Dec. 2016 | Mar. 2019 | Dec. 2016 | Mar. 2019 | Dec. 2016 | Mar. 2019 | |

| All counties | ||||||

| Number | 436 | —a | 731 | —a | 1,979 | —a |

| Population (thousands) | 180,042 | —a | 96,981 | —a | 46,125 | —a |

| Average county number of waivered clinicians per 100,000 population | ||||||

| All clinicians | 11.5 | 18.9 | 10.0 | 18.9 | 6.5 | 13.7 |

| Physicians | 11.5 | 14.7 | 10.0 | 14.7 | 6.5 | 9.7 |

| NPs and PAs | 0.0 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 4.0 |

| Average county buprenorphine treatment capacity per 100,000 population | ||||||

| All clinicians | 743 | 1,239 | 726 | 1,242 | 479 | 908 |

| Physicians | 743 | 1,088 | 726 | 1,065 | 479 | 734 |

| NPs and PAs | 0 | 152 | 0 | 177 | 0 | 174 |

| Counties with no waivered clinician in 2016 or 2019 | ||||||

| Number | 81 | 57 | 206 | 159 | 1,149 | 864 |

| Population (thousands) | 2,525 | 1,280 | 4,755 | 3,068 | 15,747 | 10,018 |

| Counties with no waivered clinician in 2016 and with a waivered NP or PA in 2019 | ||||||

| Number | 0 | 24 | 0 | 48 | 0 | 286 |

| Population (thousands) | 0 | 1,206 | 0 | 1,752 | 0 | 5,609 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2017–19 on buprenorphine waivers from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the Area Health Resources Files and of data for 2016 for all counties from the Census Bureau. NOTES “Buprenorphine treatment capacity” refers to the number of patients potentially treatable with buprenorphine by all clinicians with waivers to prescribe the medication in a county per 100,000 population. NP is nurse practitioner. PA is physician assistant.

Census data not available at the time of analysis.

Before implementation of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act in December 2016, 23.0 million people lived in 1,436 counties with no clinician with a buprenorphine waiver, and 15.7 million (68 percent) of those lived in rural counties. By March 2019, 286 of these rural counties (with a combined population of 5.7 million) had acquired at least one NP or PA with a buprenorphine waiver, a 36 percent decrease in the number of people without a waivered provider in their home county.

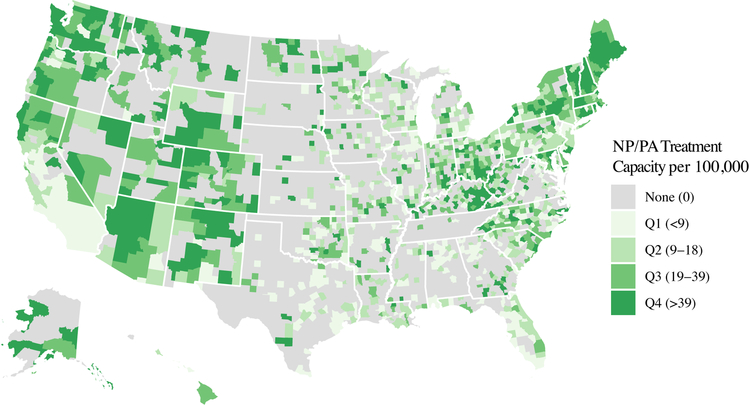

By March 2019, there was substantial geographic variation in the buprenorphine treatment capacity of NPs and PAs, with some states (such as Maine and New Hampshire) having waivered NPs or PAs in every county and others having few counties with any waivered NPs or PAs (exhibit 2). For example, only three of the ninety-five counties in Tennessee had an NP or PA with a waiver. This variation is not necessarily related to the supply of physicians with buprenorphine waivers in the same areas.

Exhibit 2.

Nurse practitioner (NP) and physician assistant (PA) buprenorphine treatment capacity per 100,000 people in 2019, by county

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2017–19 on buprenorphine waivers from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NOTES “Buprenorphine treatment capacity” in this exhibit refers to the number of patients potentially treatable with buprenorphine by NPs or PAs with waivers to prescribe the medication in a county per 100,000 population. NPs and PAs by default start with a waiver for a maximum of thirty patients, which can be expanded to a hundred patients after twelve months.

Counties With High Versus Low Nurse Practitioner And Physician Assistant Buprenorphine Waiver Adoption

By March 2019, 637 rural counties with twenty-four million people (52 percent of the total rural population) had at least one NP or PA with a buprenorphine waiver (see appendix exhibit 3 for details on these counties).27 In these counties in March 2019, an average of 9.5 percent of all NPs and 4.2 percent of all PAs had waivers. Compared to rural counties with no waivered NP or PA, rural counties with at least one waivered NP or PA in March 2019 had substantially higher total buprenorphine treatment capacity (1,440 versus 332 per 100,000 population; p < 0.001) and nearly twice as many opioid-related overdose deaths in 2016 per 100,000 population (12.0 versus 6.1; p = 0.02). In rural counties with the highest proportion of waivered NPs and PAs, 25.2 percent of NPs and 11.6 percent of PAs had waivers by March 2019 (appendix exhibit 3).27 Urban and small to medium metro counties in March 2019 had similar relationships by the proportion of NP and PAs with buprenorphine waivers, such as higher treatment capacity in counties with the highest proportion of NP and PA waivers. See appendix exhibits 4 and 5 for details on these counties.27

Association Of Scope of Practice Regulation With Nurse Practitioner And Physician Assistant Adoption Of Buprenorphine Waivers

From 2017 to 2019, rural counties in states with full NP scope of practice had significantly faster growth in NP buprenorphine treatment capacity, compared to those in states with restricted scope of practice (exhibit 3). By March 2019, this pattern of growth had led to rural counties in states with full scope of practice having twice as many waivered NPs per 100,000 population, compared to those in states with restricted scope of practice (5.2 versus 2.5) (exhibit 4). Rural counties in states with full NP scope of practice in March 2019 also had more waivered physicians per 100,000 population (14.2 versus 8.0).

Exhibit 3.

Growth in buprenorphine treatment capacity per 100,000 people in rural counties for nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) in 2016–19, by state scope of practice regulation

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2017–19 on buprenorphine waivers from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NOTES The Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which enabled NPs and PAs to obtain waivers to prescribe buprenorphine, took effect in January 2017. “Buprenorphine treatment capacity” is defined in the notes to exhibit 2 and in this exhibit shows either NP or PA treatment capacity as labeled. “Full” and “restricted” scopes of practice are explained in the text. The appendix contains a list of states in each scope of practice category (see note 27 in text). The p value for the difference in slope between full and restricted NP scope of practice states is <0.001, and the value for PA scope of practice states is 0.12. We used linear regression at the county-month level with county fixed effects to estimate the p values for trends. This is distinct from the cross-sectional regression models in Exhibit 4. We used robust standard errors clustered at the state level.

Exhibit 4:

Buprenorphine waiver adoption of nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) and overall treatment capacity in rural counties in March 2019, by state scope of practice (SOP) as of 2017

| NP SOP | PA SOP | Adjusted difference in county average between full and restricted SOP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restricted | Full | Restricted | Full | NP SOP | PA SOP | |

| Counties | 1,328 | 651 | 1,202 | 777 | —a | —a |

| All-provider treatment capacity | 819 | 1,140 | 937 | 867 | 285**** | −130** |

| Physicians | ||||||

| Number of Waivered Physicians per 100,000 | 8.0 | 14.2 | 9.6 | 9.8 | 2.8**** | −1.8 |

| Proportion with waivers (%) | 5.5 | 6.7 | 5.8 | 6.1 | 2.1*** | −2.0**** |

| NPs | ||||||

| Number of Waivered NPs per 100,000 | 2.5 | 5.2 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 2.3**** | −0.7* |

| Proportion with waivers (%) | 4.2 | 8.9 | 4.9 | 6.5 | 3.2**** | −1.3* |

| PAs | ||||||

| Number of Waivered PAs per 100,000 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.2 | −0.3* |

| Proportion with waivers (%) | 2.3 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 2.6 | −0.6 | −0.9 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2017–19 on buprenorphine waivers from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the Area Health Resources Files. NOTES “Buprenorphine treatment capacity” is defined in the notes to exhibit 2. “Full” and “restricted” scopes of practice are explained in the text. This exhibit includes only rural counties, defined as those outside of a Metropolitan Statistical Area. Adjusted p values for the difference in clinician supply between counties with full versus restricted SOPs are estimated from separate regression models with each supply variable as an outcome, controlling for all of the county demographics listed in online appendix table 3 (see note 27 in text) and the number of physicians per 100,000. This is a distinct cross-sectional analysis from Exhibit 3.

Not applicable.

p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

In contrast, rural counties in states with and without full scope of practice for PAs had similar slight decreases in the proportion of PAs with a waiver (p = 0.12 for difference in growth between full vs. restricted using county fixed effects, exhibit 3) from 2017 to 2019. By March 2019, rural counties in states with full PA scope of practice had lower buprenorphine capacity overall, if anything (exhibit 4), after adjustment for county-level demographics, and similar or decreased proportions of waivered NPs, compared to states with restricted PA scope of practice.

The relationship between NP scope of practice regulation and NP waiver adoption by March 2019 was similar in large and small to medium metro counties—though smaller proportions of NPs and PAs in these groups of counties had waivers, compared to the proportion in rural counties. See appendix exhibits 6 and 7 for details on these counties.27

Discussion

Using a comprehensive national database with information through March 2019, we found that over 12,000 NPs and PAs had obtained buprenorphine waivers, many of whom were located in counties with no prior waivered provider. In rural counties with the highest waiver adoption rates, one in four NPs acquired a waiver—despite the barrier of a twenty-four-hour training requirement. The magnitude of waiver adoption in a period of just over two years is likely a reflection of the significant demand across the country for greater access to OUD treatment and the willingness of many medical professionals to serve this vulnerable and high-need population. Our analysis complemented the larger scope of practice literature, which has found that expanded NP autonomy is generally associated with improved access to care.31,32 Because our analysis did not assess prescribing, we are unable to examine the association between the change in the NP and PA workforce and prescribing of buprenorphine. However, our results suggest that the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act is having its intended effect, particularly in rural areas that had few or no clinicians with buprenorphine waivers before 2017.

Though the spread of buprenorphine waivers among NPs and PAs was a national phenomenon, rural counties experienced the largest change in their workforce. The majority of new waivered providers in rural areas in the period 2017–19 were NPs or PAs, and rural areas had by far the largest population gaining access to a clinician with a buprenorphine waiver. Rural counties with the highest burden of opioid-related mortality also had the highest proportion of NPs and PAs with waivers by 2019, which suggests that NPs and PAs in communities with the greatest need for more treatment were also more likely to respond to this demand by acquiring waivers.

State scope of practice regulation for NPs, but not for PAs, had a strong association with the magnitude of waiver adoption in rural and urban counties. We were unable to determine the causal relationship between scope of practice and waiver adoption, due to possible confounding by unobserved differences between states with full and those with restricted scope of practice—such as local attitudes about addiction treatment. One illustration of the difference between these two groups of states is the positive association between new physician waiver uptake and full NP scope of practice, which is not likely to have a strong causal connection. Therefore, one explanation for the difference between them in waiver adoption could be lower numbers of waivered physicians per capita in states with restricted scope of practice, rather than NP scope of practice.

On the other hand, there are plausible mechanisms that can connect restricted NP scope of practice with slower waiver adoption for NPs. One is that many NPs in restricted scope of practice states face a number of regulatory barriers. For example, in Tennessee NPs and PAs are specifically barred from prescribing buprenorphine.33 It may also be difficult for NPs in states with restricted scope of practice to acquire a buprenorphine waiver if their supervising or collaborating physician does not also have and use a waiver, and unfortunately many physicians are not interested in treating OUD or prescribing buprenorphine.34

The lack of association of PA scope of practice with PA waiver adoption likely reflects the clinical specialties of PAs—as well as their more limited autonomy in many states, compared to that of NPs. While over 70 percent of NPs nationally practice either primary care or psychiatry,35 two specialties that regularly prescribe buprenorphine, only 26 percent of PAs practice primary care, and fewer than 2 percent are in psychiatric settings.36 Given their focus on many specialties outside of primary care, PAs are also more likely to practice in settings with a supervising specialist physician who does not prescribe buprenorphine or treat OUD. Therefore, the primary limitation to PA waiver adoption may not be scope of practice, but the smaller population of PAs in a clinical setting where buprenorphine prescribing is feasible.

Policy Implications

Our analysis has implications for current and future policy on access to buprenorphine. The first is that the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act has had a rapid and significant impact on the availability of waivered providers, especially in rural areas. This represents an important step in addressing access to evidence-based treatment for people in all parts of the country. Second, patterns of waiver adoption after implementation of the act show that the NP—and, to a more limited extent, the PA—workforce is a significant and rapidly growing resource for potentially expanding access to treatment for OUD.37 Given that NPs are more likely to treat rural, Medicaid-covered, and other vulnerable patient populations than physicians are,12,38 lowering barriers for NPs to prescribe buprenorphine could improve access to buprenorphine in ways that expanded physician waivers might not achieve. Third, restrictive NP scope of practice laws are predictably associated with fewer adoptions of new waivers. It is important to note that our study design could not separate the potential influence of unobserved differences between states with restricted and those with full scope of practice from the causal effect of scope of practice regulation. However, to the extent that scope of practice could play a role in the growth of NP and PA waivers, we posit that the difference in adoption between the two groups of states has more to do with tighter scope of practice regulation inhibiting waiver adoption than with the freedom of full scope of practice promoting waiver adoption.

Conclusion

Our results show that the expansion of buprenorphine waivers enabled by the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act has promoted the availability of buprenorphine prescribers using the NP and PA workforce as a key vehicle, particularly in rural areas. We observed empirical clues that these changes may be inhibited in states with restricted NP scope of practice. The rapid growth of NPs and PAs as buprenorphine providers is a promising development in the national movement to expand access to OUD treatment in rural areas. Nevertheless, engaging people with OUD is a complex challenge that will require a suite of other efforts to accompany the increased availability of evidence-based treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

An earlier version of this article was presented at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in Washington, D.C., June 3, 2019. Michael Barnett is retained as an expert witness for plaintiffs in lawsuits against opioid manufacturers. This work was funded in part by the National Institute on Aging (Grant No. K23 AG058806-01 to Barnett). Barnett reports receiving consulting fees unrelated to this work from Greylock McKinnon and Associates.

Bios for 2019–00859_Barnett

Bio 1: Michael L. Barnett (mbarnett@hsph.harvard.edu) is an assistant professor of health policy and management in the Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, and a primary care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, Massachusetts.

Bio 2: Dennis Lee is a research assistant in the Department of Health Policy and Management, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health.

Bio 3: Richard G. Frank is the Margaret T. Morris Professor of Health Economics in the Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, in Boston.

Notes

- 1.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knudsen HK, Abraham AJ, Roman PM. Adoption and implementation of medications in addiction treatment programs. J Addict Med. 2011;5(1):21–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder: proceedings of a workshop—in brief. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wakeman SE, Barnett ML. Primary care and the opioid-overdose crisis—buprenorphine myths and realities. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volkow ND, Jones EB, Einstein EB, Wargo EM. Prevention and treatment of opioid misuse and addiction: a review. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(2):208–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haffajee RL, Bohnert ASB, Lagisetty PA. Policy pathways to address provider workforce barriers to buprenorphine treatment. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6, Suppl 3):S230–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiscella K, Wakeman SE, Beletsky L. Buprenorphine deregulation and mainstreaming treatment for opioid use disorder: X the X waiver. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):229–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrilla CHA, Moore TE, Patterson DG, Larson EH. Geographic distribution of providers with a DEA waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder: a 5-year update. J Rural Health. 2019;35(1):108–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beetham T, Saloner B, Wakeman SE, Gaye M, Barnett ML. Access to office-based buprenorphine treatment in areas with high rates of opioid-related mortality: an audit study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(1):1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrilla CHA, Coulthard C, Patterson DG. Prescribing practices of rural physicians waivered to prescribe buprenorphine. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6 Suppl 3)):S208–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xue Y, Smith JA, Spetz J. Primary care nurse practitioners and physicians in low-income and rural areas, 2010–2016. JAMA. 2019;321(1):102–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Society of Addiction Medicine. Summary of the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act [Internet]. Rockville (MD): ASAM; c 2019. [cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.asam.org/advocacy/issues/opioids/summary-of-the-comprehensive-addiction-and-recovery-act [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrilla CHA, Patterson DG, Moore TE, Coulthard C, Larson EH. Projected contributions of nurse practitioners and physicians assistants to buprenorphine treatment services for opioid use disorder in rural areas. Med Care Res Rev. 2018. August 9 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iglehart JK. Expanding the role of advanced nurse practitioners—risks and rewards. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1935–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donelan K, DesRoches CM, Dittus RS, Buerhaus P. Perspectives of physicians and nurse practitioners on primary care practice. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1898–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Politico staff. Scope of practice: how can we expand access to care? Politico [serial on the Internet]. 2016. June 20 [cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.politico.com/story/2016/06/scope-of-practice-health-care-224571

- 18.Phillips SJ. 30th annual APRN legislative update: improving access to healthcare one state at a time. Nurse Pract. 2018;43(1):27–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Governors Association. The role of physician assistants in health care delivery [Internet]. Washington (DC): NGA; 2014. September 22 [cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.nga.org/center/publications/health/the-role-of-physician-assistants-in-health-care-delivery-2/ [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spetz J, Toretsky C, Chapman S, Phoenix B, Tierney M. Nurse practitioner and physician assistant waivers to prescribe buprenorphine and state scope of practice restrictions. JAMA. 2019;321(14):1407–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Health Resources and Services Administration. Data downloads [Internet]. Rockville (MD): HRSA; [cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: https://data.hrsa.gov/data/download [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC WONDER [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): CDC; [last reviewed 2019 Sep 26; cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Center for Health Statistics. NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties [Internet]. Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; [last reviewed 2017 Jun 1; cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data_access/urban_rural.htm [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barnes H, Richards MR, McHugh MD, Martsolf G. Rural and nonrural primary care physician practices increasingly rely on nurse practitioners. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(6):908–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The six key elements of physician assistant practice are defined by the American Academy of PAs as: “‘licensure’ as the regulatory term,” “full prescriptive authority,” “scope of practice determined at the practice level,” “adaptable collaboration requirements,” “cosignature requirements determined at the practice level,” and “number of PAs a physician may collaborate with determined at the practice level.” See American Academy of PAs.; The six key elements of a modern PA practice act [Internet]. Alexandria (VA): AAPA; [last updated 2017 Jan; cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.aapa.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Issue-brief_Six-key-elements_0117-1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barton Associates. PA scope of practice laws [Internet]. Peabody (MA): Barton Associates; [cited 2019 Oct 11]. Available from: https://www.bartonassociates.com/locum-tenens-resources/pa-scope-of-practice-laws [Google Scholar]

- 27.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 28.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): KFF; 2019. September 20 [cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/ [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors. State fact sheets [Internet]. Washington (DC): NASADAD; [cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: https://nasadad.org/state-fact-sheets/ [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein BD, Sorbero M, Dick AW, Pacula RL, Burns RM, Gordon AJ. Physician capacity to treat opioid use disorder with buprenorphine-assisted treatment. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1211–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Traczynski J, Udalova V. Nurse practitioner independence, health care utilization, and health outcomes. J Health Econ. 2018;58:90–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xue Y, Ye Z, Brewer C, Spetz J. Impact of state nurse practitioner scope-of-practice regulation on health care delivery: systematic review. Nurs Outlook. 2016;64(1):71–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore DJ. Nurse practitioners’ pivotal role in ending the opioid epidemic. J Nurse Pract. 2019;15(5):323–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huhn AS, Dunn KE. Why aren’t physicians prescribing more buprenorphine? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;78:1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Association of Nurse Practitioners. NP fact sheet [Internet]. Austin (TX): AANP; [updated 2019 Aug; cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: https://www.aanp.org/about/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet [Google Scholar]

- 36.National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. 2018 statistical profile of certified physician assistants: annual report [Internet]. Johns Creek (GA): NCCPA; [cited 2019 Oct 15]. Available from: https://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/2018StatisticalProfileofRecentlyCertifiedPAs.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 37.Auerbach DI, Staiger DO, Buerhaus PI. Growing ranks of advanced practice clinicians—implications for the physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):2358–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buerhaus PI, DesRoches CM, Dittus R, Donelan K. Practice characteristics of primary care nurse practitioners and physicians. Nurs Outlook. 2015;63(2):144–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.