Abstract

The distribution of random parameters in, and the input signal to, a distributed parameter model with unbounded input and output operators for the transdermal transport of ethanol are estimated. The model takes the form of a diffusion equation with the input, which is on the boundary of the domain, being the blood or breath alcohol concentration (BAC/BrAC), and the output, also on the boundary, being the transdermal alcohol concentration (TAC). Our approach is based on the reformulation of the underlying dynamical system in such a way that the random parameters are treated as additional spatial variables. When the distribution to be estimated is assumed to be defined in terms of a joint density, estimating the distribution is equivalent to estimating a functional diffusivity in a multi-dimensional diffusion equation. The resulting system is referred to as a population model, and well-established finite dimensional approximation schemes, functional analytic based convergence arguments, optimization techniques, and computational methods can be used to fit it to population data and to analyze the resulting fit. Once the forward population model has been identified or trained based on a sample from the population, the resulting distribution can then be used to deconvolve the BAC/BrAC input signal from the biosensor observed TAC output signal formulated as either a quadratic programming or linear quadratic tracking problem. In addition, our approach allows for the direct computation of corresponding credible bands without simulation. We use our technique to estimate bivariate normal distributions and deconvolve BAC/BrAC from TAC based on data from a population that consists of multiple drinking episodes from a single subject and a population consisting of single drinking episodes from multiple subjects.

Keywords: Distributed parameter systems, Random abstract parabolic systems, Population model, Linear semigroups of operators, System identification, Deconvolution, Transdermal alcohol biosensor

1. Introduction

Alcohol researchers and clinicians have long recognized the potential value of being able to monitor alcohol consumption levels in naturalistic settings. The ability to do so could advance understanding of individual differences in how people choose to drink, respond to alcohol, and behave while drinking, and how patterns and quantities of consumption relate to social versus problematic drinking. There are not adequate methods, however, for passively recording naturalistic drinking in ways that produce accurate quantitative data. Biosensors that measure transdermal alcohol concentration (TAC), the amount of alcohol diffusing through the skin, have been available for several decades and have the potential for passively collecting quantitative levels of alcohol [39, 41, 42]. Their efficacy is based on the observation that the concentration of ethanol in perspiration, to some extent, correlates with the level of alcohol concentration in the blood [28]. These devices have been used effectively to monitor whether individuals consume any alcohol (e.g., for court-mandated monitoring of abstinence [40]). The breath analyzer, which is based on a simple principle from elementary chemistry, Henry’s Law [23], is reasonably robust and consistent across individuals and ambient conditions thus allowing for the straight forward conversion of breath alcohol concentration (BrAC) to blood alcohol concentration (BAC). However, because there are variations in the rate at which alcohol diffuses through the skin across individuals and within individuals across environmental conditions, it is challenging to meaningfully interpret TAC levels quantitatively. To wit, TAC levels do not consistently correlate with BrAC or BAC, which are the standard measures of alcohol level intoxication among alcohol researchers and clinicians, and follow a relatively consistent relationship to one another across individuals and environmental conditions. Because raw TAC data does not consistently map directly onto BrAC/BAC across individuals and drinking episodes, alcohol researchers and clinicians have yet to adopt TAC devices as a fundamental tool.

Over the past decade, our research team (and others, see, for example, [16, 17, 18]) has been developing methods to address this conversion problem and produce reliable quantitative estimates of BrAC/BAC (eBrAC/eBAC) from TAC data. To date, we have taken a strictly deterministic approach to converting TAC to eBrAC/eBAC. We created a two-step system that used individual calibration data (i.e., simultaneously-collected breath analyzer BrAC measurements and biosensor TAC measurements) to fit first principles physics/physiological-based models to capture the propagation of alcohol from the blood, through the skin, and its measurement by the TAC sensor (i.e. the forward model). We then deconvolved eBrAC/eBAC from TAC measurements for all other drinking episodes without requiring any additional BrAC measurements. This procedure has produced good results (e.g. [12, 19, 32]), and has been used in alcohol related consumption and behavioral studies (e.g. [20, 27]).

The preliminary studies cited above have indicated that at least a portion of the dynamics of the system are not being captured by our models. In addition, the calibration protocol has limitations, including that the procedure for collecting the individual calibration data is burdensome for both researchers and participants, and that it is not always feasible to conduct (e.g., for clinicians and lay individuals who do not have access to an alcohol administration laboratory or with patients who are trying to abstain). These drawbacks significantly reduce the feasibility of using these devices. In a series of recent studies (e.g. [35, 36, 37]), we have investigated the construction of a population model, which uses our first principles models to describe the dynamics common to the entire population (i.e., all individuals, devices, and environmental conditions) and then to attribute all un-modeled sources of uncertainty observed in individual data (e.g., variations in human physiology, biosensor hardware, environmental conditions) to random effects. We assume that there is a single underlying mathematical framework that describes the system dynamics that are common to all individuals, environments, and devices in the population (e.g., the physics-based model for the transport of alcohol from the blood, through the skin, and measurement by the sensor), but that individuals in the population exhibit variation in the model parameters (e.g., the rate at which the alcohol is transported, evaporates, etc.). We assume that the sensor measures the sum or mean of all of these effects. We refer to the underlying first principles physics-based model with random parameters combined with the distribution of these parameters (in the form of parameterized families of probability measures or, more precisely, joint probability density functions) based on a sample of training data from the population as our estimated population model. In [37] we developed the abstract approximation and convergence theory for fitting or training the population model. In [35] we applied the theory developed in [37] to the alcohol biosensor problem discussed above. In this paper, we are concerned with using the fit population model to deconvolve an estimate for the input to the model, i.e. the BrAC signal, from the output of the model, i.e. the TAC signal, for an individual who is a member of the population but was not included in the training data set. In addition to estimating the BrAC based on the TAC, borrowing terminology from Bayesian theory, we want to use the distribution of the random parameters to obtain credible bands for the estimated BrAC. That is, a 100α percent credible band is a region surrounding the estimated BrAC signal for which the probability that the true BrAC signal lies in that region is at least α. Our approach is based on two recent papers on random abstract parabolic systems ([21, 34]) and on an abstract framework for uncertainty quantification and the estimation of probability measures from data for random dynamical systems [4].

An outline of the remainder of the paper is as follows. In Section 2 we develop a model for the transdermal transport of ethanol and its measurement by the biosensor in the form of an initial-boundary value problem for a diffusion equation with input and output on the boundary. The input to the system is BrAC and the output is the biosensor measured TAC. In Section 3 we consider abstract parabolic systems with unbounded input and output operators with random parameters and show how, using the ideas from [21], they can be reformulated as deterministic abstract parabolic systems in appropriately constructed Bochner spaces. Our population model is of this form. In Section 4 we formulate the problem of training or fitting the population model and briefly review our finite dimensional approximation and convergence results from [35] and [37], as they are fundamental to our approximation and convergence results for the input estimation or deconvolution problem, which is the focus of this paper and in particular, Section 5. In Section 6, we discuss the matrix representations of the various operators and functionals that are central to our abstract framework. In Section 7 we present numerical results for two examples involving actual experimental/clinical data. A final eighth section has some analysis of the results presented in Section 7 along with a number of concluding remarks, and in particular, a discussion of the relationship between our treatment here and inverse problems in general in a Bayesian context [10, 13, 38].

2. A Mathematical Model of Transdermal Alcohol Transport

In this section, we will derive the system of mathematical equations that we use to model the transport of ethanol through the skin. Let t be the temporal variable and let η be the spatial variable. Let φ(t, η) represent the concentration of ethanol in units of moles/cm2 in the epidermal layer of the skin at time t seconds and depth η cm. We consider the following system

| (2.1) |

| (2.2) |

| (2.3) |

| (2.4) |

| (2.5) |

where the one dimensional diffusion equation (2.1) represents the diffusion of ethanol through the epidermal layer of skin (which does not contain any blood vessels) with thickness L cm and D being the diffusivity coefficient in units of cm2/sec. The boundary condition (2.2) represents the evaporation of ethanol on the skin surface, η = 0, where α > 0 is the proportionality constant in cm/sec units. The boundary condition (2.3) models the transport of ethanol between the epidermal layer and the dermal layer (which does have blood vessels), where the proportionality constant β > 0 is in units of moles/(cm×sec×BAC/BrAC units), since the input, u(t), is in BAC/BrAC units denoting the ethanol concentration in the blood or exhaled breath. In (2.4) φ0 is the initial concentration of alcohol in the skin which will typically be assumed to be zero reflecting the assumption that there is no alcohol in the epidermal layer at time t = 0, the start of a drinking episode. Finally, equation (2.5) is called the observation equation and it denotes that the relationship between the TAC sensor reading and the ethanol concentration on the skin surface is linear with a proportionality constant, γ > 0, in units of (TAC units×cm2)/moles, since y(t) is measured in TAC units.

Using elementary change of variables, (2.1)-(2.5) can be converted into an equivalent dimensionless system involving only two dimensionless parameters, q = [q1,q2] (see [35]). The transformed system is of the same form as (2.1)-(2.5) with D = q1, L = α = γ = 1, and β = q2. Note that in the system (2.1)-(2.5), the input u (i.e. the BAC or BrAC) and the output y (i.e. the TAC) are both on the boundary of the spatial domain.

3. Random Abstract Parabolic Systems

In this section we reformulate the system given in (2.1)-(2.5) abstractly in a functional analytic/operator theoretic Gelfand triple setting. Let H and V be in general complex Hilbert spaces with V densely and continuously embedded in H. Then V ↪ H ↪ V* where V* is the topological dual of V. Let ⟨·,·⟩ denote the H inner product and let |·|, ‖·‖ denote the norms on H and V, respectively. Let Q ⊆ ℝp denote the set of admissible parameters, let dQ denote a metric on Q, and assume that Q is compact with respect to dQ. For q ∈ Q, let a(q;·,·) : V × V → ℂ be a bounded and coercive (both, uniformly in q, for q in the compact set Q) sesquilinear form. (The λ0-shifted form a(q;·,·) + λ0 ⟨·,·⟩ coercive for some λ0 ∈ ℝ is fine as well.) We also assume that for each φ,ψ ∈ V, the function q → a(q;φ,ψ) is measurable with respect to all measures π(θ), in some family of measures parameterized by a vector of parameters θ, where θ ∈ Θ ⊂ ℝr for some positive integer r. This family of measures and its parameterization will be made more precise below (see also [35]).

Under these conditions, for each q ∈ Q, the sesquilinear form a(q;·,·) defines a bounded linear operator A(q) : V → V* by ⟨A(q)ψ1,ψ2 ⟩V*,V = a(q;ψ1,ψ2) ∈ V, where ⟨·,·⟩V*,V denotes the duality pairing which is the extension via continuity of the H inner product from H × V to V* × V. By appropriately restricting the domain of the operator A(q), it is possible to consider it as an unbounded linear operator on H or V *. Moreover, it can also be shown that the operator A(q) defined above is the infinitesimal generator of an analytic or holomorphic semigroup, {T(t;q) = eA(q)t, t ≥ 0} of bounded linear operators on V, H, or V* (see [5, 6, 43]).

The fact that the input u and output y in the system (2.1)-(2.5) are on the boundary of the domain, requires that some care be exercised in the definitions of the input and output operators in our formulation of the problem (see [35]). Let b(q), c(q) denote elements in V * with the respective maps q ↦ < b(q), ψ > V*,V and q ↦ < c(q), ψ > V*,V measurable on Q with respect to all measures π(θ) for ψ ∈ V, where < ·,· >V *,V again denotes the duality pairing between V and V*. We assume further that ‖b(q)‖V*, ‖c(q)‖V* are uniformly bounded for a.e. q ∈ Q. Then, for q ∈ Q, define the operators B(q) : ℝ → V* by ⟨B(q)u, φ⟩V*,V = ⟨b(q),φ⟩V*,Vu and C(q) : L2([0,T], V) → ℝ by , for u ∈ ℝ, φ ∈ V, and ψ ∈ L2([0, T], V ), and consider the input/output state space system given by

| (3.1) |

| (3.2) |

| (3.3) |

where u ∈ L2(0,T) is the input, y(t) is the output, and x(t) = φ(t,·) is the state variable. Then by applying the theory for infinite dimensional control systems with unbounded input and output and, in particular, systems described by PDEs with input and output on the boundary of the domain, developed in, for example, [11] and [31], the mild solution of (3.1)-(3.2) can be written as

| (3.4) |

where the state x is in and depends continuously on u ([26]).

Our model for transdermal alcohol transport described by the system (2.1)-(2.5) can be put in the abstract form given by the system of equations (3.1)-(3.3) by making the following identifications. We let H = L2(0,1) and V = H1(0,1) with their standard inner products and the corresponding norms. Consequently we have the continuous and dense embeddings, and hence the Gelfand triple H1(0,1) ↪ L2(0,1),↪ H−1(0,1). We define the sesquilinear form a(q;·,·) : V × V → ℝ as

| (3.5) |

and the operators B(q) and C(q) as

| (3.6) |

for ψ ∈ V. With these definitions, it is not difficult to show that the boundedness, coercivity, and measurability assumptions on a(q;·,·), b(q), and c(q) are satisfied. A more detailed description of the equaivalence between the model (2.1)-(2.5) and the abstract system (3.1)-(3.3) can be found in [35, 37].

Now assume that the parameters, q, are random and are denoted by the p-dimensional random vector . We assume that has support where , and has distribution described by a probability measure π0 or distribution function F0.

Now with the parameters q replaced by the random vector , the operators , , , and the semigroup all become random, as does the abstract system given in (3.1)-(3.3) and its solution given in (3.4). However, by relying on some recent ideas presented in [21] and [34], we are able to reformulate the abstract random system (3.1)-(3.3) as a deterministic system wherein the randomness is embedded in the underlying abstract spaces. Moreover, this new system continues to be abstract parabolic in that the underlying state transition dynamics are given by a bounded coercive sesquilinear form. Consequently, a holomorphic semigroup based representation for this new system analogous to the one described above and given by equations (3.1)-(3.3), (3.5), and (3.6) can be obtained. In this way the underlying randomness in the system effectively becomes invisible, thus allowing us to develop parameter estimation and deconvolution schemes and finite dimensional approximation and convergence theories exactly as we would in the deterministic case. Indeed, the problem of estimating the distribution of the random vector now becomes essentially the same as estimating a spatial variable dependent diffusivity in a conventional diffusion or heat equation, albeit one with a higher dimensional spatial domain.

Define the Bochner spaces and which form the Gelfand triple with the pivot space and identification of with (see [21]). Then, for π a probability measure with corresponding distribution function F, we define the π-averaged sesquilinear form by

| (3.7) |

where . It is now straightforward to show that is also bounded and coercive [21]. Then, as was the case previously, defines a bounded linear map which is also the infinitesimal generator of an analytic semigroup, , of bounded linear operators on , , or depending on its domain. Defining the linear operators and by

| (3.8) |

| (3.9) |

for u ∈ ℝ and (see [35, 37]), we can now rewrite the system (3.1)-(3.3) as

| (3.10) |

| (3.11) |

| (3.12) |

Then, the mild solution of (3.10)-(3.11) is given by

| (3.13) |

and moreover, from (3.12), we obtain that

| (3.14) |

The solution of system (3.1)-(3.2) is π-almost everywhere equivalent to the solution of the system (3.10)-(3.11) which is given by (3.13) (see [21] and [34]). In place of the input output system (3.1)-(3.3) with random parameters q, we consider the system (3.10)-(3.12) with solution given by (3.13) and (3.14). Since the solution to (3.10)-(3.11) given in (3.13) does not explicitly involve any randomness, we can use the tools of linear semigroup theory to state and prove our approximation and convergence results for both the distribution estimation problem and the deconvolution problem (i.e the problem of estimating the input u based on observations of the output y). We refer to the system (3.10)-(3.12), or equivalently, (3.14), as a population model.

4. Estimating the Population Model

In this section we briefly summarize how we estimate the population model by estimating the distribution of the random parameters, , in (3.10)-(3.12). The details can be found in [35, 37].

Let τ > 0 denote a sampling time. We consider zero order hold inputs of the form u(t)= uj, t ∈ [jτ, (j + 1)τ), j = 0,1,…. Then, it follows from (3.10)-(3.12) that

| (4.1) |

| (4.2) |

with where , and . By assumption = 0. By the analyticity of the semigroup, , the operators and are in fact bounded (see [5, 6, 11, 26, 31, 43]). It follows that , j = 0,1,2,…, and moreover, if we make the continuous dependence assumption that

then it is not difficult to show (using the Trotter-Kato theorem from linear semigroup theory, for example, see also,[22, 43]) that ∈ C(Q; V), j = 0,1,2,…. In addition, the coercivity assumption implies that, without loss of generality, we may assume that is invertible with bounded inverse, it follows that . Finally, by the definition of , we can write

| (4.3) |

where is the corresponding operator when we write the discrete-time version of the system (3.1)-(3.3) (see [35]).

We assume that ν data sets have been collected, and a statistical model of the form

| (4.4) |

where in (4.4), π0 is some unknown probability measure to be estimated, and εi,j, j = 0,…,μi, i = 1,…,ν, represent measurement noise that are assumed to be independent and identically distributed with mean 0 and common variance σ2.

We let , and where Θ is a parameter set which is a compact subset of ℝr for some r. Then, in attempting to estimate the distribution π0 (F0), we assume that has support of the form , and that its distribution can be described by a probability measure of the form and corresponding distribution function having the joint probability density function .

Remark 4.1

Our assumption here of the existence of a density is motivated by the convergence theory developed earlier in [37] which is the basis for the current treatment. Indeed, in [37] it was our desire to construct a complete approximation and convergence theory for the estimation of the distributions of random parameters in abstract parabolic systems. The convergence arguments in [37] rely heavily on linear semigroup theory, and in particular the Trotter-Kato semigroup approximation theorem (see, for example, [22, 30]. The Trotter-Kato theorem is essentially a semigroup-based version of the classical Lax-Richtmyer Equivalence theorem [24] which states that stability together with consistency of an approximation scheme for a dynamical system are equivalent to convergence. Unfortunately we were unable to argue the consistency of our Galerkinbased schemes if the underlying probability measures were not absolutely continuous with respect to Lebesgue measure and hence that the existence of an associated Radon-Nikodym derivative can not be guaranteed. More specifically, unless we were willing to impose stronger, less desirable and not readily checked assumptions on the semigroups, their approximations, and the probability measures, we were unable to make the required rather delicate estimates for the Lebesgue-Stieltjes type integrals that appear in the consistency arguments. We do believe however, that computationally, our scheme is likely to work even when a density does not exist (see [3, 4]). But in the interest of presenting a theory here with no gaps, we have assumed a-priori that the measures are absolutely continuous with respect to Lebesgue measure and hence that densities do in fact exist.

Letting be the subset of ℝp × ℝp given by , we then state the estimation problem as follows: We seek

| (4.5) |

where is given as in (4.3) with , j = 0,1,…,μi − 1 and i = 1,2,…,ν.

Let . Then if we require that the maps be continuous on ℝP × ℝP × Θ for π-a.e. and there exist constants 0 < γ, δ < ∞ such that , for π-a.e. , then we can show that the map is continuous. Moreover, using compactness, we can conclude that the estimation problem stated above has a solution, . The system (4.1)-(4.3) together with given in (4.5) is referred to as the estimated population model corresponding to the data sample . We note that under appropriate additional assumptions, we are able to argue that can be interpreted as estimators and that they are consistent [35].

Determining in (4.5) and then actually using the population model to solve the inverse or deconvolution problem requires finite dimensional approximation. Let and for each N = 1,2,…. Let and be such that , and , for each N = 1,2,… and set . Then define , , and to be a finite dimensional subspace of for each N = 1,2,…. Now, define the operator to be such that and . Then, let be the orthogonal projection of onto and define . Then, define by

| (4.6) |

where . Note here that it can be shown that , t ≥ 0 for some constants M > 0 and ω0 which are independent of N (see [36, 37]). Then, define the operators and by

| (4.7) |

and

| (4.8) |

where and u ∈ ℝ. Then, assuming that ν data sets are given, the finite dimensional approximating problems are stated as

| (4.9) |

where is given by

| (4.10) |

| (4.11) |

for each i = 1, 2,…,v, with , and .

The systems (4.10),(4.11) together with given by (4.9) are referred to as the approximating estimated population models. Under the assumption that for any , we have

| (4.12) |

we are able to prove that [35, 37]

| (4.13) |

for some λ ≥ ω0 and every where and denote the resolvent operators of and at λ. Then using (4.9) and a version of the Trotter-Kato theorem that allows for the state spaces to depend on the parameters ([2, 36, 37]), we are able to establish that

| (4.14) |

for every uniformly on compact t-intervals of [0,∞). It is then not difficult to show that there exists a subsequence that converges to as j → ∞ where is a solution of the estimation problem (4.5).

In implementing this scheme, we used linear splines for the η discretization and characteristic functions for the q1 and q2 discretizations. Matrix representations of the operators , and could then be obtained by using the Galerkin formulation of the operators appearing in the system (4.10)-(4.11) (see Section 6 below for further details). In solving the finite dimensional optimization problems (4.9), the requisite gradients of the cost functional JN can be computed efficiently and with no truncation error via the adjoint method (see [25, 35, 37]).

5. Input Estimation or Deconvolution

We formulate the problem of estimating or deconvolving the input to the population model, (3.10)-(3.12) (or in discrete time, (4.1)-(4.2)) as a constrained, regularized optimization problem that ultimately takes the form of a quadratic programming or linear quadratic tracking problem (see, for example, [26]), albeit with a performance index whose evaluation requires the solution of an infinite dimensional state equation. We denote the parameters that determine the distribution of by ρ, where , optimally fit parameters by ρ*, where , and the support of the random parameters determined by the optimally fit parameters, ρ*, by Q* (see Section 4 above). We then consider the population model (4.1)-(4.2) in which the input {uj} is obtained by zero-order hold sampling a continuous time signal. That is, we assume that the input to the population model is given by {} with , where τ > 0 is the length of the sampling interval and is a continuous time signal that is at least continuous (to allow for sampling) on an interval [0,T]. In our framework, we first use this model with the training data to estimate the distribution of the random parameters (i.e. to obtain ρ*). Then, we seek an estimate for the input based on this model and the estimated distribution of the random parameters. We consider our input estimate, , to be a random variable being a function of the random parameters, , as well as a function of time. Therefore, let ∈ S(0,T), where and let be a compact subset of S(0,T).

The input estimation problem is then given by

| (5.1) |

where the term is related to the regularization with ‖ · ‖S(0,T) a norm on the space S(0,T), the details of which will be discussed later, and

| (5.2) |

with , j = 0,1,…,K, , l = 1,2,…,K where , and . We note that the coercivity assumption implies without loss of generality (via a standard change of variable), that we may assume that the operator has a bounded inverse, . It is also important to indicate here that, due to the assumption that is also a function of , we consider the operator now to be defined from into as

| (5.3) |

Solving the problem stated in (5.1) requires finite dimensional approximation. Let N,M,L be multi-indices defined by N = (n, m1, m2), M = (m, m1, m2), and L = (N, M). Note that whenever we use the notation N, M, or L → ∞, we mean all components of these multi-indices go to infinity. For each M, let be a closed subset of which is contained in a finite dimensional subspace of S(0, T). The sets are, of course, therefore compact.

We will require the following approximation assumption on the subsets , or more typically, the finite dimensional spaces they are contained in, .

Assumption 5.1

For each , there exists a sequence {} with , such that

| (5.4) |

Let the Bochner spaces and which in the usual manner, form the Gelfand triple , be as they were defined in Section 3. For each N let denote a finite dimensional subspace of and let denote the orthogonal projection of onto . We require the assumption that the subspaces have the following approximation property.

Assumption 5.2

For each

| (5.5) |

We note that it can often be shown using the Schmidt inequality (see [33]) that spline-based subspaces typically satisfy (5.5).

Define the operators by

| (5.6) |

where . We note that as is the case with the operator , coercivity implies that without loss of generality, the operators given in (5.6) are invertible with inverses that are uniformly bounded in N. Moreover, once again, as a result of coercivity, standard estimates can be used to show that

| (5.7) |

as N → ∞ (see, for example, [5, 6, 37]). It then follows from the Trotter-Kato semigroup approximation theorem [5, 6, 30] that

| (5.8) |

as N → ∞.

We now state the finite dimensional approximating deconvolution problems:

| (5.9) |

where

| (5.10) |

with , j = 0,1,…,K, , l = 1,2,…,K, with , the operator given by (5.3), and , being the extension of the orthogonal projection of onto to . Note that the existence of the extension of the orthogonal projection operator can be proved by using the fact that is a dense subset of and the Riesz Representation theorem.

Now, consider the following lemma which we will need to prove our convergence theorem.

Lemma 5.1.

For l = 1,2,…,K, let the bounded linear functionals hl(ρ*) and on be given by and , respectively. Then, under Assumption 5.2, we have that converges weakly (i.e. pointwise) to hl(ρ*) in (and therefore, their respective Riesz representers in converge weakly in as well) as N → ∞, uniformly in l on any finite set of indices. That is

| (5.11) |

as N → ∞, for all , l = 1,2,…,K, uniformly in l on any finite set of indices. Moreover, if is a sequence in with , we have that as L→ ∞ uniformly in l on any finite set of indices.

Proof. The last claim in the statement of the Lemma of course follows immediately from the weak convergence in (5.11). To establish (5.11), we note that in light of the approximation assumption, Assumption 5.2, on the finite-dimensional subspaces , (5.5), and the strong convergence in (5.7) and (5.8), the result will follow if we can show that the operators converge strongly to the identity on the space . But this follows easily from the approximation condition (5.5) and standard density arguments. □

Now, we are ready to state and prove the theorem regarding convergence of the solutions of approximating problems to the solution of the original infinite dimensional problem.

Theorem 5.1.

For each L, the finite dimensional approximating optimization problem given in (5.9) admits a solution denoted by . Moreover, under Assumptions 5.1 and 5.2 there exists a subsequence of , , with as k → ∞, with a solution to the infinite dimensional estimation problem given in (5.1).

Proof. The existence of a solution to each of the finite dimensional approximating optimization problems given in (5.9) follows from (5.10) and therefore the continuity of JL, and the compactness of . Now let {} be a convergent sequence in with and as M → ∞, . Then if and , j = 1, 2, K, it follows that as M → ∞, j = 1,2,…,K. It follows from the lemma that

| (5.12) |

It follows from (5.12) that as L → ∞.

Let be a sequence of solutions to the finite dimensional approximating optimization problems given in (5.9). The compactness of implies that there exists a subsequence of , with as k → ∞. Then for any it follows that

| (5.13) |

where Lk = (Nk, Mk), and the sequence with are the approximations to guaranteed to exist by the approximation assumption on the subsets given in Assumption 5.1, equation (5.4), and thus, is a solution of the estimation problem stated in (5.1). □

We note first that the above theorem continues to hold if S(0,T) is chosen as . In addition, it is not difficult to see that the way we have formulated the deconvolution problem and its finite dimensional approximations given in (5.1) and (5.9), respectively, the resulting optimization problems take the form of a linear quadratic tracking problem where the systems to be controlled are, respectively, the population model, (4.1),(4.2) and its finite dimensional approximation, (4.10), (4.11). Consequently, it becomes possible to adapt some ideas from [1] to obtain a somewhat different and in some ways stronger convergence result than that given in Theorem 5.1 above. We now describe briefly how this is done.

Now let be a closed and convex subset of S(0,T) and for each M, let be a closed convex subset of which is contained in a finite dimensional subspace of S(0,T). Note that the maps and from into ℝ and from into ℝ, respectively, are strictly convex. Consequently solutions and to the optimization problems (5.1) and (5.9), respectively, exist and are unique. Moreover, the sequence is bounded. If not, there would exist a subsequence, with , and therefore that . But then this would contradict the fact that for any , we have that

| (5.14) |

where Lk = (Nk,Mk), and the sequence with are the approximations to guaranteed to exist by the approximation assumption on the subsets given in Assumption 5.1, equation (5.4). Then since was assumed to be closed and convex, it is weakly closed. Therefore, there exists a weakly convergent subsequence, of with , for some . In addition, the convexity and (lower semi-) continuity of J and JL yield that J and JL are weakly sequentially lower semi-continuous. Then, Assumptions 5.1 and 5.2, Lemma 5.1 together with the weak lower semicontinuity of J and JL imply that

| (5.15) |

where again Lk = (Nk,Mk), and the sequence with are the approximations to guaranteed to exist by the approximation assumption on the subsets given in (5.4) (Assumption 5.1), and hence that, is the solution of the estimation problem stated in (5.1). Finally we note that the strict convexity of and imply that the sequence itself, must in fact converge weakly to the unique solution, , of the estimation problem stated in (5.1), and because the norm in S(0,T) is bounded above by J, that the sequence itself must in fact converge strongly, or in the norm in S(0,T), to the unique solution, , of the estimation problem stated in (5.1).

6. Matrix Representations of the Operators and Regularization

In this section we describe how the matrix representations for the finite dimensional operators that appear in the approximating population model, (4.10), (4.11), are computed. We also discuss some issues related to the regularization terms that appear in the optimization problems (5.1) and (5.9). The state, , j = 0,1,…,μi, i = 1,2,…,ν, in the population model described by system (4.1)-(4.2), is a function of the distributed variables, η, and the random parameters q1 and q2. It is these dependencies that are discretized in our framework. Recall that the state space for the approximating systems (4.10)-(4.11) is the finite dimensional subspace of . Recall also that these spaces must satisfy the approximation property given in Assumption 5.2, equation (5.5). We construct the spaces using linear B-splines defined with respect to the uniform mesh on the interval [0,1] and use the standard 0th order (i.e. piecewise constants) B-splines and defined with respect to the uniform mesh on the intervals for i = 1,2, respectively. Then, letting N = (n,m1,m2) as before, and letting P denote the multi-index P = (j,j1,j2), we use tensor products to define as and set . Results from [33] can be used to establish equation (5.5) of Assumption 5.2.

The input signal, , is a function of time, t, and also the random parameters q1 and q2 and is therefore an element of the space S(0,T) defined in Section 5. To construct finite dimensional subspaces, , of S(0,T) that have the approximation property given in equation (5.4) of Assumption 5.1 (see [33]), we again use standard linear B-spline polynomials defined with respect to the usual uniform mesh, , on the interval [0,T] to discretize the time dependency. We use the same 0th order B-splines for q1 and q2 with respect to corresponding uniform mesh on the intervals and , respectively, to discretize the dependence on the random parameters. Letting M = (m,m1,m2) and R be the multi-index R = (i,j1,j2), we again use tensor products to serve as the basis for the approximating subspaces. We define as and set . In this way, any can be written as

| (6.1) |

Now that bases for the approximating spaces have been chosen, the definitions of the finite dimensional operators , and given in Section 5 are sufficient to compute corresponding matrix representations. Note that since the finite dimensional input operators act on the input signal which depends on t, and have range in , their matrix representations will depend on the dimension of both and . Consequently their matrix representations will depend on the multiindex L = (N,M). In this way, the matrix representation of the system (4.10)-(4.11) is of the form

| (6.2) |

where the vectors are coefficients of the basis elements and the vectors are formed from the coefficients in the expansion given in (6.1). In the system (6.2) the matrices and are (n + 1)m1m2×(n+1)m1m2, is an (n+1)m1m1×mm1m2 matrix, and is an (n + 1)m1m1 dimensional row vector. The state variables are (n + 1)m1m2 × 1 vectors and the inputs are mm1m2 × 1 vectors. The matrix representation of the operators , and in terms of the matrices , , , and appearing in (6.2) can be used to obtain the matrix representations for the approximating convolution kernels , l = 1,2,…,K, which because of their dependence on , we shall now refer to as . In the numerical studies presented in the next section the sampling interval was taken to be τ = 1 min. It follows that T/τ = K in (5.1) and (5.9). In the case that the sensor data, , has not been collected at 1-min time intervals, we re-sample by interpolating the collected data with a cubic spline.

The cost functionals defined in (5.1) and (5.9) include regularization terms in the form of the square of the norm on S(0,T), ‖ · ‖S(0,T), which we take to be given by

| (6.3) |

where r1,r2 > 0 are regularization parameters in the form of nonnegative weights. While choosing regularization parameters can entail a mix of art and science, we chose r1 and r2 as the solution of the following optimization problem based on the original training data used to estimate the distribution of the random parameters in the model.

Recall the training data from Section 4 consisting of ν data sets

| (6.4) |

After using the training data to estimate the distribution of the random parameters, we use the approach discussed in Section 5 together with the training TAC observations, , given in (6.4) to estimate the BrAC inputs also given in (6.4). Denote these estimates by . We then use these estimates of the input together with the approximating population model, (5.2), to obtain estimates for the corresponding TAC, . Note that both the and the are functions of the weights, r1 and r2 appearing in the cost functional for the input estimation problem. We then define the performance index

| (6.5) |

where , and choose the regularization parameters, and , to use in our scheme as

| (6.6) |

where is given by (6.5).

We note that since the approximating optimization problems given in (5.9) are in fact constrained (i.e. we want all the components of to be nonnegative) linear problems, in practice, we solve them as quadratic programming problems. Moreover, in finite dimensions, the two integrals in the expression for the regularization term, , given in (6.3), become quadratic forms in the vectors with the two positive definite symmetric matrices, denoted by and , having entries that are the easily computed inner products of the basis elements for the q dependencies of the elements in . By appropriately placing the matrix representations for the approximating filters in the block matrix , the approximating optimization problem given in (5.9) now takes the equivalent form

| (6.7) |

where come from (6.6), is the Kmm1m2 dimensional column vector of the coefficients of the , and is the K + Kmm1m2 dimensional column vector consisting of the K TAC data points followed by Kmm1m2 zeros. The optimization problem given in (6.7) is solved subject to the constraint ≥ 0.

7. Numerical Results

A WrisTAS™7 alcohol biosensor designed and manufactured by Giner, Inc. of Waltham, MA was used for TAC measurements in the first dataset, and a Secure Continuous Alcohol Monitoring System (SCRAM) device manufactured by Alcohol Monitoring Systems (AMS) in Littleton, Colorado (see Figure 7.1) was used to collect data for the second example.

Figure 7.1:

Alcohol Biosensor Devices: Left panel: The Giner WrisTAS. Right panel: The AMS SCRAM.

We assumed that the joint pdf of the two (now assumed to be random) parameters that appear in the model (2.1)-(2.5) have compact support and takes the form of a truncated exponential family of distributions (see [35, 37]). We let their supports be determined by the four parameters in the two vectors, , as [a1,b1] × [a2,b2], and that their distribution was a truncated bivariate normal with mean μ and covariance matrix Σ and joint pdf denoted by consequently

| (7.1) |

In each example, a portion of the data (henceforth referred to as the population or training data) was used to fit the population model and a portion was held back for cross-validation. The population model and the cross-validation data were then used to estimate BrAC from the measured TAC. We also obtained 75% credible bands for our BrAC estimates. To do this, we generated 1,000 random samples from the population distribution (i.e. the fit truncated bivariate normal), and selected the ones lying in the circular region R ⊂ [a1,b1] × [a2,b2] centered at the mean where R was chosen so that . Since our scheme provides an estimate of BrAC as a function of q = (q1,q2) (and of course of time, as well), we could obtain the corresponding samples of the BrAC by simply evaluating this function of at the samples of the distribution. We refer to this as Method 1. We also examined the case where the estimated input is considered to be a function of time only (and therefore not of q = (q1,q2) or ). This approach is referred to as Method 2. In this case, we used the operator as it was defined in (3.8) and followed the same steps with regard to the data as in the case depending on both t and q. However, in this case, the credible bands had to be determined via simulation. We used both the adjoint method [25] together with the sensitivity equations [35, 37], and finite differencing, independently, to compute gradients and both methods yielded the same result. We determined the optimal regularization parameters and by solving the optimization problem given in (6.5) or (6.6). In both of the examples that follow we took n = m1 = m2 = 4 and m = 6Th, where Th is the number of hours of TAC data available for the drinking episode(s) being analyzed. In estimating the population models, each BrAC/TAC dataset in the population was used to find estimates for the parameters, q = (q1,q2) via deterministic nonlinear least squares. Sample means and covariances were then used as initial guesses when the optimization problem given in (4.9) was solved.

7.1. Example: Single Subject, Multiple Drinking Episodes; Data Collected with the WrisTASTM7 Alcohol Biosensor

One of the co-authors of this paper (S. E. L.) wore a WrisTAS™7 alcohol biosensor device for 18 days. During each drinking episode, she collected BrAC data (i.e. blew into a breath analyzer) approximately every 30 minutes. The first drinking episode was conducted in the laboratory and BrAC was measured every 15 minutes until it returned to 0.000. Then she wore the biosensor device for the following 17 days and consumed alcohol ad libitum. During those days, BrAC was measured every 30 minutes starting from the beginning of the drinking session until its value returned to 0.000. The WrisTAS™7 measured and recorded ethanol level at the skin surface every 5-minutes. It is important to note that during those 17 days, the data was collected in a naturalistic setting.

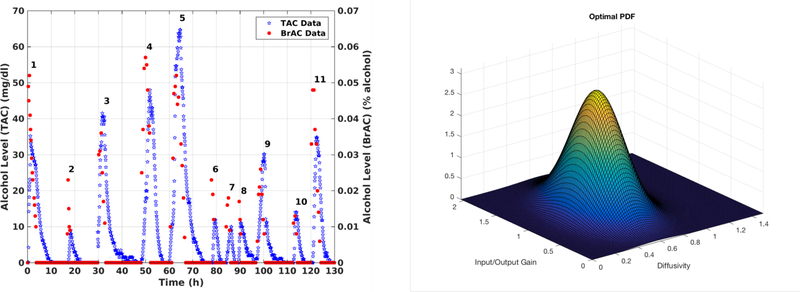

The plot in the left panel of Figure 7.2 shows the measured BrAC and TAC over 11 drinking episodes. Using this plot, we visually stratified the dataset into two groups. The first group contains the data belonging to drinking episodes 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, 11. In each of these drinking episodes, the peak BrAC value was higher than the bench calibrated peak TAC value. The second group contains the remaining drinking episodes, 3, 5, 9, and 10 for which the peak TAC value was higher than the peak BrAC value. In the example we present here, we considered only the first group. Our results for the second group and all 11 drinking episodes taken together all at once were similar. In the first group, we randomly chose the drinking episodes 4 and 8 for cross-validation and used the remaining five, episodes 1, 2, 6, 7, and 11, to train the population model (i.e. these five episodes served as the training or population data). We obtained the optimal parameters for the truncated bivariate normal distribution as follows: the truncated support was determined to be and , and the optimal values for the mean and covariance matrix were found to be and .

Figure 7.2:

Left panel: BrAC and TAC measurements for Example 7.1. Right panel: Optimal pdf obtained using the data from drinking episodes 1, 2, 6, 7, and 11 as the population or training dataset.

The plot of the optimal joint density function corresponding to these optimal parameters is shown in the right panel of Figure 7.2. In addition, the optimal regularization parameters were found to have the values and for the regularization term in (5.1) as defined in (6.3) in the case the input depends on both t and q. Those values became and in the case u depends only on t.

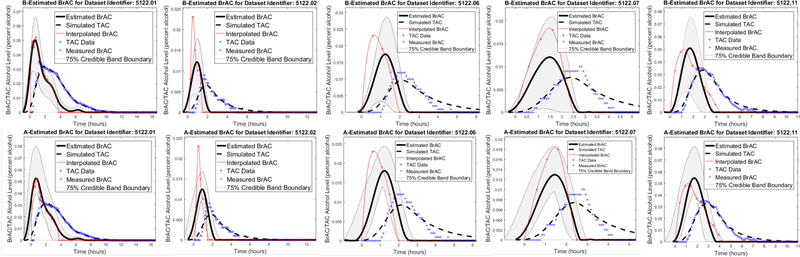

As described previously in this section, we took two different approaches in estimating the input: (Method 1) we sought is a function of both t and and (Method 2) we assumed that u was a function of t only. The estimation results for the training drinking episodes 1, 2, 6, 7, 11 that are obtained by each of the methods separately can be seen in Figure 7.3. The cross-validation results for the drinking episodes 4 and 8 are shown in the left panel of Figure 7.4.

Figure 7.3:

Example 7.1 Results. Top row: BrAC estimates for the training datasets assuming the input depends on both time and the random parameters, Bottom row: BrAC estimates for the training datasets assuming the input depends only on time.

Figure 7.4:

Example 7.1 Results. Left Panel: Top row: BrAC estimates for the cross-validation datasets assuming the input, , depends on both time, t, and the random parameters, ; Bottom row: BrAC estimates for the training datasets assuming the input, u, depends only on time, t. Right Panel: Upper Left: Expected value of the impulse response function or convolution kernel together with 75% credible intervals for population model in Example 7.1, Upper Right: Impulse response function or convolution kernel for population model in Example 7.1 as a function of q = (q1,q2), Lower Left: Estimated BrAC, or input signal, at time when the expected value is at its peak as a function of q = (q1,q2) for drinking episode 1 in Example 7.1, Lower Right: Probability density function for the estimated BrAC, or input signal, at time when the expected value is at its peak for drinking episode 1 in Example 7.1. The points marked with red dots in the q1,q2 plane in the plots in the upper right and lower left corners of the right panel are the samples from the bivariate normal distribution that were used to compute the 75% credible bands.

In the upper left corner of the right panel of Figure 7.4 we have plotted the mean or expected value of the approximating impulse response function or convolution kernel for the population model, given by

| (7.2) |

l = 1,2,…,K, together with the 75% credible band. Recall that for each l = 1,2,…,K, , or at least its representer, is an element and thus is a function of , and consequently, the mean and credible bands can be obtained by simply substituting in samples of . Note that as a result of the fact that the bases for our approximating subspaces are tensor products, the impulse response function for the scheme in which we simply sought an estimate for BrAC that was a function of t only (and not of q1 and q2), turn out to be the mean of , l = 1,2,…,K, , and as such are plotted in the right panel of this figure as well. In the upper right corner of the right panel of Figure 7.4, the surface, , as a function of q1 and q2 at the time at which is at its peak, is plotted. In the lower left corner of the right panel of Figure 7.4 we have plotted the estimated BrAC for drinking episode 1 as a function of q1 and q2 at the time at which its mean is at its peak, and finally in the lower right corner of the right panel of Figure 7.4 the probability density function for the estimated BrAC at the time it is at its peak is plotted. Once again we note that since the estimated BrAC at each time t is an element of and thus is a function of , this pdf can be obtained by simply generating samples of from the bivariate normal distribution determined by the parameters ρ* and then simply substituting them into the obtained expression for the estimated BrAC, or eBrAC, (6.1).

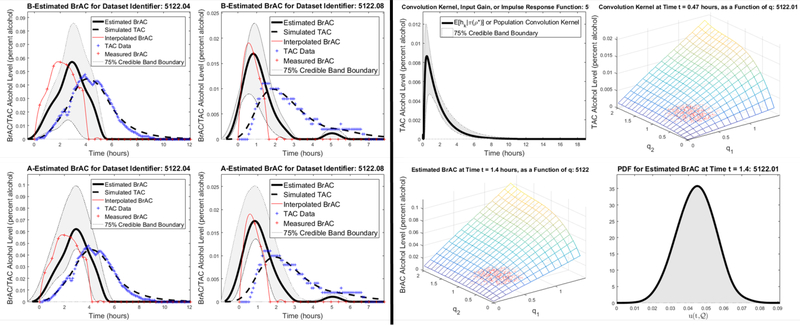

7.2. Example: Multiple Subjects; Data Collected with the Alcohol Monitoring Systems (AMS) SCRAM Alcohol Biosensor

In this example, we used datasets collected from multiple subjects at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign using the AMS SCRAM alcohol biosensor. In this study 60 subjects or participants were given a gender and weight-adjusted dose of alcohol (0.82 g/kg for men, 0.74 g/kg for women). This dosage was selected so as to yield a peak BrAC of approximately .08%. The alcoholic beverage was administered in 3 equal parts at 0 min, 12 min, and 24 min, and participants were instructed to consume their beverages as evenly as possible over these intervals. All participants were then asked to provide breathalyzer readings at approximately 30-minute intervals. The SCRAM sensor was worn and provided transdermal readings also at a rate of one approximately every 30 minutes. This data was collected for a study other than the one being reported on here. The design protocol for that study called for each subject’s alcohol challenge session to end when their BrAC dipped below 0.03% and/or their transdermal readings had reached a peak and begun to descend (see [20]). Since typically BrAC leads TAC, in 37 of the original 60 sessions, when the session was halted, the TAC signal had either not yet started its descent, or had not been decreasing for a sufficient amount of time to establish an elimination trend. For this reason, these sessions were deemed inappropriate for our study here, and were eliminated from further consideration. Of the remaining 23 sessions, 5 displayed what we would characterize as physiologically anomalous behavior in that the TAC led the BrAC. This would be inconsistent with our modeling assumption that there is no alcohol present in the subjects body at time t = 0. The possible causes for this might include the participants failure to adhere to the protocol laid out in the study design, an error in data recording, a sensor hardware malfunction, or the TAC sensor coming into contact with alcohol vapor either as the alcohol dose was being prepared or administered, or from some other source containing ethanol such as skin creams, etc. We eliminated these 5 subjects from further consideration in our study as well, leaving us with 18 usable participant data sets.

We first used our deterministic model to estimate the values for q = (q1,q2) for each of the 18 datasets separately. We stratified the datasets by selecting the data of eight of the subjects, subjects 1, 8, 9, 10, 20, 21, 22, and 23, whose q values clustered around the origin. We then used subjects 9 and 21 for cross-validation and used the remaining six subjects, numbers 1, 8, 10, 20, 22, and 23, for training.

Following the same steps as we did in Example 7.1 above, for this training population we found the optimal values for the support of the pdf of the truncated bivariate normal distribution to be and . We determined the optimal mean and covariance matrix to be and . The optimal regularization parameters for the case in which depends on both time, t and the random parameters, (i.e. Method 1), were found to be and . When u depended only on time t (i.e. Method 2), they were and . The plots of the optimal pdf, the BrAC curve estimates for the training data used to fit the population model and for the crossvalidation data, for the convolution kernel and for the pdfs were all analogous to those shown above for Example 7.1 in plots 7.2, 7.3, and 7.4.

In addition to estimates for the continuous BrAC signal, clinicians and alcohol researchers are also interested in a number of statistics associated with the BrAC curve for an identified drinking episode. Specifically, for each drinking episode, they look at: I: The maximum or peak value of the BrAC, II: The time (since the start of the episode) at which the peak value of the BrAC is attained, III: the area under the episode’s BrAC curve, IV: the BrAC elimination rate, and V: the BrAC absorption rate. The BrAC elimination rate is defined to be the peak BrAC value divided by the amount of time that elapses from the time at which the peak BrAC value was attained until the first zero BrAC measurement (more precisely the time at which the BrAC level first sinks below a predefined threshold), and the BrAC absorption rate is defined to be the peak BrAC value divided by the amount of time that elapses from the last zero BrAC measurement (more precisely the time at which the BrAC level first rises above the predefined threshold) until the time at which the peak BrAC value was attained. In Table 7.1 we provide these statistics for the drinking episodes in Example 7.2. In Table 7.2 we use our estimated BrAC surfaces and samples from the bivariate normal distribution corresponding to the parameters ρ* to compute 75% credible intervals for each of these statistics. Note that in these tables, the episodes and subjects without an asterisk (*) were used in training the population model, while those marked with an asterisk were held back for cross-validation. All of these results were computed using Method 1 (BrAC a function of both time and and ).

Table 7.1:

Example 7.2 Statistics: I: Maximum value (percent alcohol), II: Time of maximum (hours), III: Area under the curve (percent alcohol × hours), IV: Elimination rate (percent alcohol per hour), V: Absorption rate (percent alcohol per hour).

| Sub. | BrAC | Estimated BrAC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | I | II | III | IV | V | |

| 1 | 0.0820 | 2.3333 | 0.3822 | 0.0132 | 0.0351 | 0.0918 | 4.2833 | 0.4333 | 0.0206 | 0.0175 |

| 8 | 0.0740 | 2.0500 | 0.2392 | 0.0180 | 0.0361 | 0.0422 | 1.8333 | 0.1229 | 0.0147 | 0.0149 |

| 9* | 0.0640 | 3.0000 | 0.2568 | 0.0130 | 0.0213 | 0.0379 | 2.9833 | 0.1251 | 0.0124 | 0.0100 |

| 10 | 0.0750 | 0.3833 | 0.2590 | 0.0109 | 0.0542 | 0.0798 | 2.8333 | 0.2559 | 0.0278 | 0.0211 |

| 20 | 0.01020 | 1.6833 | 0.3820 | 0.0203 | 0.0606 | 0.0649 | 2.9333 | 0.2459 | 0.0146 | 0.0167 |

| 21* | 0.0820 | 2.0000 | 0.2884 | 0.0178 | 0.0410 | 0.0660 | 2.3000 | 0.2412 | 0.0177 | 0.0200 |

| 22 | 0.0810 | 2.1000 | 0.2905 | 0.0143 | 0.0386 | 0.0714 | 2.7500 | 0.2733 | 0.0180 | 0.0191 |

| 23 | 0.0390 | 2.6500 | 0.1444 | 0.0089 | 0.0147 | 0.0387 | 2.6167 | 0.1160 | 0.0126 | 0.0109 |

Table 7.2:

Example 7.2 Credible Intervals: I: Maximum value (percent alcohol), II: Time of maximum (hours), III: Area under the curve (percent alcohol × hours), IV: Elimination rate (percent alcohol per hour), V: Absorption rate (percent alcohol per hour).

| Sub. | Credible Intervals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | |

| 1 | [0.0497,0.1715] | [3.8833,4.5167] | [0.2235,0.8166] | [0.0121,0.0407] | [0.0103,0.0314] |

| 8 | [0.0206,0.0830] | [1.5667,1.9667] | [0.0553,0.2457] | [0.0085,0.0308] | [0.0080,0.0280] |

| 9* | [0.0185,0.0745] | [2.6667,3.1333] | [0.0563,0.2499] | [0.0069,0.0260] | [0.0055,0.0185] |

| 10 | [0.0398,0.1552] | [2.5500,2.9833] | [0.1200,0.5024] | [0.0162,0.0578] | [0.0114,0.0392] |

| 20 | [0.0357,0.1203] | [2.6333,3.1000] | [0.1267,0.4635] | [0.0096,0.0284] | [0.0099,0.0297] |

| 21* | [0.0343,0.1257] | [1.9833,2.4667] | [0.1163,0.4683] | [0.0102,0.0356] | [0.0115,0.0363] |

| 22 | [0.0365,0.1374] | [2.3667,2.9500] | [0.1293,0.5360] | [0.0111,0.0370] | [0.0109,0.0349] |

| 23 | [0.0194,0.0753] | [2.3500,2.7500] | [0.0542,0.2283] | [0.0074,0.0258] | [0.0059,0.0203] |

For each of the episodes in Example 7.2, we computed the percentage of BrAC statistics that fell within the approximating 75% credible intervals. We found: Statistic I: 100%, II: 38%, III: 88%, IV: 88% and V: 25%. The statistics that involved the time of the peak BrAC seemed to pose the most significant challenge for the method.

8. Discussion and Conclusion

In the two examples in the previous section, we computed estimated BrAC using two approaches, one in which we allowed the estimated BrAC signal to depend on the random parameters, and , in addition to depending on time, and the other where we sought estimated BrAC as a function of time only. The first method has the benefit of allowing for the efficient computation of credible bands by simply sampling the distribution of the random parameters and then directly substituting the samples into an expression for the estimated BrAC as a function of q1 and q2. In the second method, credible bands had to be computed via sampling and simulation. With the first method, training takes longer because of the time involved in solving the optimization problem (6.7) associated with the computation of the optimal regularization parameters. Then the deconvolution of the estimated BrAC signal and computation of the associated credible bands is very quick. On the other hand, for the second approach, the training is quicker than the first, but because of the need to simulate the deterministic (3.1)-(3.3) model with each of the random samples of and , the deconvolution and credible band determination step is significantly slower than the first approach. Since the training is off-line and the deconvolution and credible band determination is generally on-line, the first approach is desirable. In comparing the results for the two methods, we observed some, but generally not significant, differences.

Our results suggest a number of open mathematical questions that deserve further consideration. In our treatment here, although we evaluate them at specific values of q1 and q2, the surfaces we obtain for the estimated impulse response function and input and the associated convergence theory are in fact only L2 making point-wise evaluation undefined. We are currently looking at the introduction of some form of parabolic regularization [26] into the q-dependence of the population model. By doing this, it may become possible to obtain coercivity of the sesquilinear form (3.5) with respect to a stronger norm, and therefore obtain H1-like well-posedness and convergence of the approximations in the q dependence of the state, input, and output.

We are also looking at eliminating the requirement that the measures, π, be defined in terms of a parameterized density. By employing a different version of the Trotter-Kato semigroup approximation theorem (see [2]), approximating subspaces with smoother elements, and results for the approximation of measures, we conjecture that we may be able to directly apply the approximation framework developed in [3, 4] which involves the estimation of the underlying probability measures directly. Another extension in this same spirit would be to attempt to directly estimate the shape of the density rather than simply its parameters. It seems that, in this case, existing results for the estimation of functional parameters in PDEs may be directly applicable. Also, one might consider a parameterization for the random parameters in the model in terms of their polynomial chaos expansions much as is done in [21].

Of course, improved performance of the population model could potentially be obtained with higher fidelity models with higher dimensional parameterization; for example these might include the addition of an advection term, non-constant or functional coefficients (probably with finite dimensional parameterization), damped second order hyperbolic models (e.g. the telegraph equation) for diffusion with finite speed of propagation (see, for example, [29]). It would also be interesting to see if an analogous nonlinear theory could be developed for infinite dimensional systems governed by maximal monotone operators (see, for example, [7]).

In solving the infinite dimensional deconvolution, or input estimation, problem (5.1), or its finite-dimensional approximation, (5.9) or (6.7) by either Method 1 or Method 2, we have taken an optimal control approach. Indeed, we formulated the problem as a constrained, regularized, linear least squares problem or equivalently as a constrained linear quadratic tracking problem. This approach offered a number of distinct computational advantages that made it appealing for its ultimate intended use in the context of providing real time estimates from data collected by a wearable sensor. However, once the population model has been identified, this is not the only way that an estimate together with credible bands for the input or BrAC could be obtained. An alternative approach would be to formulate the problem statistically and then obtain the estimate and credible bands as part of a Bayesian framework. Treating inverse problems from the standpoint of Bayesian estimation has received a significant amount of attention in the literature over the course of the last five years (see, for example, [8, 9, 13, 38] along with a special issue of the journal Inverse Problems devoted exclusively to a Bayesian approach to inverse problems [10]).

To see how this works, at least formally, we consider an abstract representation of either the infinite dimensional model (5.2) or its finite dimensional approximation (5.10) as a statistical model of the form

| (8.1) |

where , with is our input/output model obtained in terms of the operators and semigroups defined following (5.2) (or their finite dimensional approximations defined following (5.10)) and ε ∼ represents random observation error with probability density function given by . In (8.1) denotes in (5.2) ( in (5.10)) loaded into a K-dimensional vector.

The statistical model given in (8.1) is what is known in the statistics literature as a classical mixed effects model (see, for example, [14, 15]) featuring both inter- (as captured by the population distribution described by the parameters ρ) and intra- (as given by ε) subject variation and uncertainty. In our discussion here, for illustrative purposes, we have combined both the estimation of the population model and the input estimation/deconvolution problems into a single estimation problem. But clearly the framework we are about to describe could be used to separately estimate either the population model (i.e. ρ) with the given population BAC/BrAC, or the input (i.e. ) with ρ = ρ*, ρ* having been previously estimated, Bayesian or otherwise.

In the Bayesian setting, the regularization takes the form of a prior distribution for ρ and/or in the form of a probability density function f0, (ρ,) ∼ . From (8.1), the conditional density of given () can then be expressed as

| (8.2) |

An application of Bayes Theorem together with (8.2) and the above defined prior, then yields the posterior distribution for as

| (8.3) |

As is standard with Bayesian estimators, our population model and/or BrAC estimates, and , would then be taken to be , with corresponding credible bands computed accordingly.

There is a natural relationship between the Bayesian estimator based on (8.3) and the estimates we computed earlier in Sections 4, 5 and 6 via constrained, regularized linear or nonlinear least squares methods. If we assume normality in both the observation error, , and the prior, , then the posterior distribution of u given the data is given by the conditional density

| (8.4) |

where Z denotes the normalization constant so that . In this case the estimates we find in (5.1), (5.9) or (6.7) are the Maximum A-Posteriori (MAP) estimates, the ones that maximize the posterior distribution given in (8.4) [38].

While using the Bayesian framework to estimate the BrAC () given the population model (ρ*) is appealing in that it would potentially allow us to compute credible bands that account for both the inter- and intra- individual uncertainty in the model, unfortunately there are also a number of computational challenges that would have to be overcome. There is the fact that both the quantity being estimated, the BrAC or input , and the abstract parabolic state equation relating it to the output or TAC, are infinite dimensional. Some form of reasonably high fidelity (and therefore high dimensional) finite dimensional approximation in time t, space η, and the population parameters q = (q1,q2) would be required. Consequently sampling the posterior distribution, (8.4), even if an efficient MCMC-based scheme is employed could be daunting. This is especially true in light of the fact that ultimately the goal is to have the TAC inversion scheme run in real time as part of a wearable sensor/processing/display system. One would also have to devise a way to impose the non-negativity constraint on the estimated input. On the other hand, the Bayesian framework suggests a number of interesting mathematical questions to pursue. For example, in the spirit of the results presented in Section 5, can it be established that the Bayesian estimator computed based on finite dimensional approximations to the support of the random parameters, Q, the input space , and the state spaces for the abstract population model, and and the corresponding operators, converge to the Bayesian estimator for the original infinite dimensional model. We are currently investigating this question.

Finally we note that if alcohol biosensors were to be incorporated into wearable health monitoring technology (e.g. the Fitbit and the Apple Watch), our approach would have to be modified to produce estimated BrAC in real time. This would be a challenge in light of the inherent latency of the human body’s metabolism and transdermal secretion via perspiration of ethanol and the limitations of the analog hardware in the current state-of-the-art transdermal alcohol sensors. We are currently looking at combining the ideas presented here with a look-ahead prediction algorithm based on either a hidden Markov model (HMM) or a recurrent artificial neural network (RANN).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the Alcoholic Beverage Medical Research Foundation and the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (R21AA17711 and R01AA026368-01, S.E.L. and I.G.R.), and (R01AA025969, C.E.F.).

Contributor Information

Melike Sirlanci, Email: sirlanci@usc.edu.

I. G. Rosen, Email: grosen@math.usc.edu.

Susan E. Luczak, Email: luczak@usc.edu.

Catharine E. Fairbairn, Email: cfairbai@illinois.edu.

Konrad Bresin, Email: bresin2@illinois.edu.

Dahyeon Kang, Email: dkang38@illinois.edu.

References

- [1].Banks HT and Burns JA. Hereditary control problems: Numerical methods based on averaging approximations. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization, 16(2):169–208, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Banks HT, Burns JA, and Cliff EM. Parameter estimation and identification for systems with delays. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization, 19(6):791–828, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Banks HT, Flores KB, Rosen IG, Rutter EM, Sirlanci Melike, and Thompson W. Clayton The Prohorov metric framework and aggregate data inverse problems for random PDEs. Communications in Applied Analysis, 22(3):415–446, 2018. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Banks HT and Clayton Thompson W. Least squares estimation of probability measures in the Prohorov metric framework. Technical report, DTIC Document, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Thomas Banks H and Kunisch Karl Estimation Techniques for Distributed Parameter Systems. Birkhauser, Boston-Basel-Berlin, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Banks HT and Ito K. A unified framework for approximation in inverse problems for distributed parameter systems. Control Theory Advanced Technology, 4(1):73–90, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Barbu Viorel P.. Nonlinear Semigroups and Differential Equations in Banach Spaces. Noordhoff International Publishing, Leyden, The Netherlands, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tan Bui-Thanh Carsten Burstedde, Ghattas Omar, Martin James, Stadler Georg, and Wilcox Lucas C.. Extreme-scale UQ for Bayesian inverse problems governed by PDEs In SC12, November 10–16. IEEE, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tan Bui-Thanh Omar Ghattas, Martin James, and Stadler Georg. A computational framework for infinite-dimensional Bayesian inverse problems Part I: The linearized case, with application to global seismic inversion. SIAM J. Sci. Stat. Comp, 35(6):A2494A2523, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Calvetti Daniela, Kaipio Jario P., and Somersalo Erkki. Inverse problems in the Bayesian framework. Inverse Problems, 30:1–4, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Curtain RF and Salamon D. Finite-dimensional compensators for infinite-dimensional systems with unbounded input operators. SIAM J. Contr. and Opt, 24(4):797–816, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dai Zheng, Rosen IG, Wang Chuming, Barnett Nancy, and Luczak Susan E. Using drinking data and pharmacokinetic modeling to calibrate transport model and blind deconvolution based data analysis software for transdermal alcohol biosensors. Mathematical Biosciences and Engineering, 13(5):911–934, July 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Dashti Masoumeh and Stuart Andrew M.. The Bayesian approach to inverse problems In Ghanem R et al. , editor, Handbook of Uncertainty Quantification, pages 311–428. Springer International Publishing; Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Davidian M and Giltinan D. Nonlinear Models for Repeated Measurement Data. Chapman and Hall, New York, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Demidenko E. Mixred Models, Theory and Applications. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dougherty DM, Charles NE, Acheson A, John S, Furr RM, and Hill-Kapturczak N. Comparing the detection of transdermal and breath alcohol concentrations during periods of alcohol consumption ranging from moderate drinking to binge drinking. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 20:373–381, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dougherty DM, Hill-Kapturczak N, Liang Y, Karns TE, Cates SE, Lake SL, and Roache JD. Use of continuous transdermal alcohol monitoring during a contingency management procedure to reduce excessive alcohol use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 142:301–306, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dougherty DM, Karns TE, Mullen J, Liang Y, Lake SL, Roache JD, and Hill-Kapturczak N. Transdermal alcohol concentration data collected during a contingency management program to reduce at-risk drinking. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 148:77–84, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Dumett Miguel A., Rosen IG, Sabat J, Shaman A, Tempelman L, Wang C, and Swift RM Deconvolving an estimate of breath measured blood alcohol concentration from biosensor collected transdermal ethanol data. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 196(2):724–743, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fairbairn CE, Bresin K, Kang D, Rosen IG, Ariss T, Luczak SE, Barnett NP, and Eckland NS. A multimodal investigation of contextual effects on alcohols emotional rewards. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, to appear. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Claude Jeffrey Gittelson Roman Andreev, and Schwab Christoph. Optimality of adaptive Galerkin methods for random parabolic partial differential equations. J. Computational Applied Mathematics, 263:189–201, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kato T. Perturbation Theory for Linear Operators, Second Ed. Springer-Verlag, New York, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Labianca Dominick A.. The chemical basis of the breathalyzer: A critical analysis. J. Chem. Educ, 67(3):259–261, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lax PD and Richtmyer RD. Survey of the stability of linear finite difference equations. Comm. Pure Appl. Math, 9:267–293, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Levi AFJ and Rosen IG. A novel formulation of the adjoint method in the optimal design of quantum electronic devices. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization, 48(5):3191–3223, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lions JL. Optimal Control of Systems Governed by Partial Differential Equations Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften in Einzeldarstellungen mit Besonderer Berücksichtigung der Anwendungsgebiete. Springer-Verlag, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Luczak Susan E., Rosen I. Gary, and Wall Tamara L. Development of a real-time repeated-measures assessment protocol to capture change over the course of a drinking episode. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 50(1):1–8, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nyman E and Palmlöv A. The elimination of ethyl alcohol in sweat. Acta Physiologica, 74(2):155– 159, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Okubo Akira and Levin Simon A.. Diffusion and Ecological Problems, Modern Perspectives, Second Edition. Springer, New York, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Pazy A. Semigroups of Linear Operators and Applications to Partial Differential Equations Applied Mathematical Sciences. Springer, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pritchard Anthony J. and Salamon Dietmar. The linear quadratic control problem for infinite dimensional systems with unbounded input and output operators. SIAM Journal on Control and Optimization, 25(1):121–144, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Rosen IG, Luczak Susan E., and Weiss Jordan Blind deconvolution for distributed parameter systems with unbounded input and output and determining blood alcohol concentration from transdermal biosensor data. Applied Mathematics and Computation, 231:357–376, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schultz MH. Spline Analysis. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Schwab Christoph and Gittelson Claude Jeffrey. Sparse tensor discretization of high-dimensional parametric and stochastic PDEs. Acta Numerica, 20:291–467, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sirlanci Melike, Luczak Susan E., Fairbairn Catharine E., Kang Dahyeon, Pan Ruoxi, Yu Xin, and Rosen IG Estimating the distribution of random parameters in a diffusion equation forward model for a transdermal alcohol biosensor. Manuscript submitted for publication, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [36].Sirlanci Melike, Luczak Susan E., and Rosen IG Approximation and convergence in the estimation of random parameters in linear holomorphic semigroups generated by regularly dissipative operators In American Contr. Conf. (ACC), pages 3171–3176. IEEE, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sirlanci Melike and Rosen IG Estimation of the distribution of random parameters in discrete time abstract parabolic systems with unbounded input and output: Approximation and convergence. Manuscript submitted for publication, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [38].Stuart AM. Inverse problems: A Bayesian perspective. Acta Numerica, pages 451–559, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Swift Robert. Transdermal alcohol measurement for estimation of blood alcohol concentration. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24(4):422–423, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Swift Robert. Direct measurement of alcohol and its metabolites. Addiction, 98:73–80, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Swift Robert M.. Transdermal measurement of alcohol consumption. Addiction, 88(8):1037–1039, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Swift Robert M., Martin Christopher S., Swette Larry, LaConti Anthony, and Kackley Nancy Studies on a wearable, electronic, transdermal alcohol sensor. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 16(4):721–725, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Tanabe H. Equations of Evolution. Monographs and Studies in Mathematics. Pitman, 1979. [Google Scholar]