Abstract

Evaluation of myocardial T1 times is conventionally limited to a single temporal snapshot of the cardiac cycle, leaving the dependence between functional and tissue characterization unexplored. We recently proposed a technique that alleviates this limitation by acquiring dynamic quantitative myocardial T1 maps. However, tradeoffs between temporal resolution, scan duration and SNR limit the spatial resolution. In this work, we propose a multi-scale locally low rank noise reduction approach without parameter-tuning to enable high acceleration rates in the acquisition, facilitating superior spatial and temporal resolutions in dynamic myocardial T1 mapping.

I. INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular MRI (CMR) has major utility in the assessment of numerous cardiomyopathies [1], [2]. Conventional techniques rely on differences in contrast between different tissue types. However, recently there has been a push for quantitative CMR parameter mapping, which enable detection of diffuse pathologies and robust inter-patient comparability. Among these, myocardial T1 mapping, which quantifies longitudinal relaxation, has shown diagnostic and prognostic promise in a range of diseases [3].

Myocardial T1 mapping techniques rely on the acquisition of multiple T1-weighted images, using different contrast-generation mechanisms, including inversion [4] or saturation [5] preparation, or a combination of both [6]. The acquisitions are commonly triggered using an electrocardigogram (ECG) signal in order to allow pixel-wise quantification. Baseline T1 weighted images are acquired using single-shot imaging, which leads to one image per cardiac cycle. However, this restricts the quantification to a single, typically end-diastolic, cardiac phase, acquired with coarse temporal resolution (200–250 ms) [3]. The single-shot acquisition further limits the spatial resolution, to an in-plane resolution of approximately 2 × 2 mm2.

In order to quantitatively analyze the T1 times in the myocardium, delineation of the myocardium from the surrounding blood pools is commonly performed manually [3], rendering the method sensitive to accurate tissue differentiation [7]. However, sub-epicardial fat, trabeculae, myocardial crypts and other structures have been shown to hamper the clear identification of the blood-myocardium interface in single-phase cardiac images [8]. Furthermore, the limited spatial resolution of these images confounds the differentiation of blood from myocardium due to partial voluming artifacts. Thus, superior temporal and spatial resolutions are necessary to improve reproducibility and to accurately identify the blood-myocardium interface in the presence of functional variability.

We have recently developed a novel method for cardiac phase-resolved and spatially resolved mapping of the native myocardial T1 times [9], enabling quantification with a temporal resolution of 40 ms. However, in order to restrict the scan times to the duration of a breath-hold, the spatial resolution of the acquisition has to be limited to the same range as the conventional single-shot images. Thus, partial voluming poses challenges to the manual delineation of the myocardial borders. Improved spatial resolution is desirable, but typically requires longer acquisition times in the presence of lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

In this study, we sought to develop a noise reduction method to improve the dynamic myocardial T1 map quantification. Images are acquired at high acceleration rates with uniform undersampling, and reconstructed using parallel imaging techniques. Subsequently, denoising is performed using low-rank properties of local neighborhoods of different sizes through the image series. Additionally, the linear reconstruction enables the use of random matrix theory results to optimally select the thresholding parameter for the neighborhood sizes. The noise reduction method is evaluated for dynamic in-vivo myocardial T1 mapping, acquired at high spatial and temporal resolutions.

II. METHODS

A. Dynamic Myocardial T1 Mapping Sequence

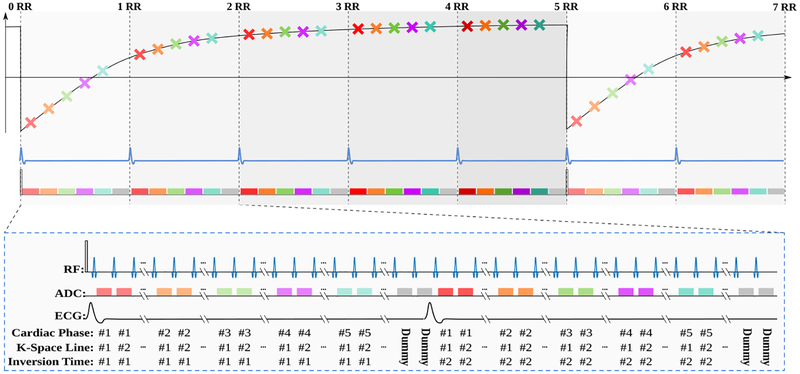

Magnetic resonance imaging was performed to quantify longitudinal magnetization recovery in the myocardium, using a steady-state Look-Locker inversion recovery technique [9], as illustrated in Figure 1. First, the magnetization is driven to the pulsed steady-state using several RF excitations with subsequent spoiling of the transverse magnetization. The magnetization is then inverted from this pulsed steady state, and read-out using continuously played FLASH pulses. Each cardiac phase, accommodates multiple (in the order of 8 to 12) imaging pulses, and accordingly, allows for acquisition of a k-space segment. Sampling the inversion recovery curve in this segmented manner is repeated over multiple heartbeats until the magnetization recovers to the pulsed steady-state. A re-inversion of the magnetization is then performed to commence the sampling of the next k-space segment. The procedure is repeated until a k-space is fully sampled for each of the cardiac phases.

Fig. 1.

The sequence diagram of the dynamic myocardial T1 mapping used in this study. Overall, the sequence acquires ncardiac cardiac phases per heart beat (five in the figure, depicted with different colors) over ncontrast heartbeats (five in the figure) that is necessary until re-recovery to pulsed steady-state for a FLASH sequence. This results in ncardiac · ncontrast images in a series that varies both in contrast and cardiac motion.

To avoid disruption from the pulsed magnetization recovery, dummy RF pulses are, if necessary, played at the end of each heart-beat. After imaging a pre-determined number of cardiac phases these excitations without corresponding imaging readout are performed until the subsequent R-wave of the ECG signal is reached. The process results in ncardiac × ncontrast images in the image series, where ncardiac is the pre-specified number of cardiac phases (of the order 10–14, depending on the heart-rate), and ncontrast is the number of different T1 weightings per cardiac phase, which corresponds to the number of heart-beats until re-recovery to the pulsed steady state (of the order of 5–6 depending on the heart-rate).

B. Multi-Scale Locally Low-Rank Noise Reduction

Locally low rank (LLR) regularization of an MR image series has been previously proposed in the context of iterative reconstructions [10], [11], [12], which enforces data consistency or the low rank constraint in an alternating manner in each iteration. For a fixed pixel location, the LLR approach extracts patches of size m1 × m2 whose top left corner is at that pixel throughout the series of N images, where the noise is typically assumed to be independent across the image series. These patches, which are positioned at the given pixel, are then vectorized and these vectors are put together to form a Casorati matrix [13], whose dimension is m1m2 × N. Due to redundancies in the image series that acquire the same anatomy over time or through contrast changes [11], [12], this Casorati matrix can be represented accurately by a low-rank matrix, which can be enforced via singular value thresholding [14]. The process is then repeated for other pixels to cover the whole image in-plane.

In our approach, we seek to avoid the processing that alternates between enforcing consistency with the acquired k-space data, and the LLR regularization of the images, while exploiting noise information that can be derived from the raw k-space data. To this end, we first perform a parallel imaging reconstruction [15] in SNR units [16]. This ensures that the underlying noise distribution in the reconstruction corresponds to a standard normal distribution. Following the extraction of the relevant local patches into a Casorati matrix, singular value thresholding is performed. Since the reconstruction is in SNR units, the threshold parameter is calculated analytically from the singular value distribution of a Gaussian random matrix, which follows a Marchenko-Pastur distribution [17], eliminating a heuristic parameter selection process. This process is repeated for overlapping patches to avoid blocking artifacts, where patches are shifted by half a patch size in each direction

Finally, a multi-scale denoising approach is pursued. Such multi-scale approaches have been used for MRI reconstruction both by changing patch sizes [18] or using a quad-tree structure [19]. In this work, we use multiple patch sizes , with their corresponding regularization parameters, derived from Marchenko-Pastur distribution. Letting be the operator that extracts the m× n block whose top-left corner is at pixel location p into a Casorati matrix and Y be the noisy image series, we solve

| (1) |

using a projection onto convex sets (POCS) approach.

C. Dynamic T1 map reconstruction

Longitudinal magnetization recovery during continuously played FLASH pulses can be described as [20]:

| (2) |

where MSS describes the pulsed steady-state, Mz(0) the starting magnetization and the apparent longitudinal relaxation time given as: , where TR is the repetition time. As the magnetization is inverted from the steady-state using a rectangular inversion pulse, the initial magnetization can be described as Mz(0) = MSS · cos(αinv). The image intensities of the processed image can be fit voxel-wise to Equation (2), using a three parameter model as, .

Due to the discrepancies between the nominal flip angle and the actual flip angle, resulting from the transmit field inhomogeneities, additional correction of is required. This is performed, using the ratio between the actual excitation flip angle α and the nominal excitation flip angle αnom, which can be approximated as , where is the nominal flip angle of the inversion pulse, and B is derived from the 3-parameter fit. Thus, the actual T1 time can be calculated using the estimated apparent T1 time from the 3-parameter fit as follows:

D. Imaging Experiments

Imaging was performed on a 3 Tesla scanner (Magnetom Prisma, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) using a 30-channel receiver coil-array. The following sequence parameters were used: TR = 5ms, echo time = 2.5ms, flip angle = 3°, bandwidth = 350 Hz/pixel, field-of-view = 300 × 225 mm2, slice thickness = 10mm, partial-Fourier = 6/8, temporal resolution = 40 ms, nominal inversion flip angle = 170°. Images were acquired in a single mid-ventricular short-axis slice.

A high in-plane spatial resolution of 1.3 × 1.3 mm2 was achieved using a parallel imaging factor of 3, with 24 reference lines in the central k-space. The scan was completed in a breath-hold duration of 18 seconds. Myocardial T1 times were assessed for the unprocessed reconstructed images and the images using the proposed noise reduction approach, via manually drawn regions-of-interest (ROIs) in the septal wall. The estimated T1 value and the spatial variability are reported as the mean and standard deviation in the ROI, respectively.

III. RESULTS

Figure 2 depicts representative baseline images of a diastolic cardiac phase acquired in a healthy volunteer. For this subject, ncardiac = 11 and ncontrast = 5, leading to an image series of length 55, which contains both contrast and cardiac motion changes. Due to the high undersampling factor used in parallel imaging, a noisy baseline is obtained (unprocessed), even though strong contrast variation and delineation between the blood pool and the myocardium are depicted between different inversion times. Visibly improved quality is obtained using the proposed approach. Detrimental noise variability within the myocardial and blood pools are alleviated, while the sharp tissue delineation and contrast variation are preserved.

Fig. 2.

Results of denoising on baseline with in-plane resolution of 1.3 × 1.3 mm2, reconstructed with GRAPPA (unprocessed) and with the proposed noise variance reduction technique (proposed).

A similar trend is observed in Figure 3, which depicts the dynamic quantitative T1 maps of all cardiac phases estimated in the same subject. Major noise variations in the baseline images deteriorate the visual quality of the quantitative maps. This effect is particularly pronounced in later cardiac phases, due to less favorable sampling of the inversion recovery curve [9]. After image denoising with the proposed approach, homogeneous T1 times are obtained across the myocardial tissue while sharp delineation of the myocardium-blood border is maintained. End-diastolic T1 times obtained from septal ROIs are in close agreement between T1 maps obtained from unprocessed (1399 ms) and denoised (1414 ms) baseline images. However, spatial variability across the septal ROI was reduced by 60% using the porpoised method, from 132.3 ms with the unprocessed data to 53.5 ms after denoising. Figure 4 depicts the T1 values through cardiac phases for a cross-section of the heart. The proposed approach maintains accurate functional representation of the cardiac motion throughout the R-R interval with no apparent temporal blurring.

Fig. 3.

Dynamic quantitative T1 maps generated without and with the proposed multi-scale LLR noise reduction technique. Homogeneous T1 values are observed with the proposed approach, with > 60% reduction in spatial variability.

Fig. 4.

T1 times through cardiac phases across a cross-section of the heart, showing no temporal blurring occurs with the proposed technique.

IV. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we proposed a multi-scale locally low rank (LLR) noise reduction approach for a dynamic myocardial T1 mapping application [9]. By utilizing this denoising method after a parallel imaging reconstruction in SNR units [16], we were also able to eliminate the need for empirical selection of regularization parameters, instead deriving them directly from random matrix theory [17].

The method, in conjunction with the sequence, was shown to enable a uniform undersampling rate of 3, which in turn yielded a superior in-plane spatial resolution of 1.3 × 1.3 mm2 and a temporal resolution of 40ms, as compared to conventional T1 mapping acquisitions with in-plane resolutions of 2 × 2 mm2 and temporal resolution of 200 − 250ms [3]. These improvements may help better delineation of the myocardium-blood interface, warranting further studies.

LLR techniques have been used in MRI, both in uniformly and randomly undersampled acquisition scenarios [10], [11], [12]. Recent studies show that while random acquisitions may have benefits at high acceleration rates and volumetric 3D coverage [21], for 2D acquisitions uniform undersampling may be superior [22]. Thus, we used uniform undersampling and parallel imaging in this study. LLR denoising has also been used in diffusion weighted brain images, although the thresholding parameters were chosen heuristically [23]. Alternative approaches for thresholding parameter determination [24], [25] were not explored in this preliminary study. Previous LLR studies in conjunction with uniform undersampling relied on the iterative SPIRiT technique for reconstruction [11], [12]. In this study, we opted for GRAPPA [15], which allows a single-step processing to generate the baseline images in SNR units. The tradeoffs between these two works were not explored.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was partially supported by NIH R00HL111410, NIH P41EB015894 and AFOSR.

REFERENCES

- [1].Kramer CM, “Role of Cardiac MR Imaging in Cardiomyopathies,” J Nucl Med, 56 Suppl 4:39S–45S, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].von Knobelsdorff-Brenkenhoff F and Schulz-Menger J, “Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in ischemic heart disease,” J Magn Reson Imaging, 36(1):20–38, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schelbert EB and Messroghli DR DR, “State of the Art: Clinical Applications of Cardiac T1 Mapping,” Radiology, 278:658–676, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Messroghli DR, Radjenovic A, Kozerke S et al. , “Modified Look-Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) for high-resolution T1 mapping of the heart,” Magn Reson Med, 52(1):141–146, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chow K, Flewitt JA, Green JD et al. , “Saturation recovery single-shot acquisition (SASHA) for myocardial T1 mapping,” Magn Reson Med, 71(6):2082–2095, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Weingartner S, Akcakaya M, Basha TA et al. , “ Combined saturation/inversion recovery sequences for improved evaluation of scar and diffuse fibrosis in patients with arrhythmia or heart rate variability,” Magn Reson Med, 71(3):1024–1034, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kellman P and Hansen MS, “T1-mapping in the heart: accuracy and precision,” J Cardio Magn Reson 16:2, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kellman P, Bandettini WP et al. , “Characterization of myocardial T1-mapping bias caused by intramyocardial fat in inversion recovery and saturation recovery techniques,” J Cardio Magn Reson 17:33, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Weingartner S, Shenoy C and Akcakaya M, “Cine T1 Mapping: B1 corrected Look-Locker inversion recovery for phase resolved T1-Mapping at 3T,” J Cardio Magn Reson, 19 Suppl 1:P172, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Trzasko J and Manduca A, “Local versus global low-rank promotion in dynamic MRI series reconstruction,” Proc. ISMRM, p. 4371, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhang T et al. , “Fast 3D DCE-MRI with sparsity and low-rank enhanced SPIRiT (SLR-SPIRiT),” Proc. ISMRM, p. 2624, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhang T, Pauly JM and Levesque IR, “Accelerating parameter mapping with a locally low rank constraint,” Magn Reson Med. 73(2):655–61, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Haldar J and Liang Z, “Low-rank approximations for dynamic imaging,” Proc. IEEE ISBI, Chicago, p. 1052–55, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cai J, Candes E and Shen Y, “A singular value thresholding algorithm for matrix completion,” SIAM J Optim, 20:19561982, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Griswold M, Jakob P et al. , “Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions(GRAPPA),” Magn Reson Med, 47:1202–10, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kellman P and McVeigh ER, “Image reconstruction in SNR units,” Magn Reson Med 54: 1439–1447, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Marchenko VA and Pastur LA, “Distribution of eigenvalues for some sets of random matrices,” Mat Sb (NS). 72(4):507–36, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Akcakaya M, Basha TA et al. , “Low-dimensional-structure self-learning and thresholding (LOST): regularization beyond compressed sensing for MRI reconstruction,” Magn Reson Med, 66:756–767, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ong F and Lustig M, ”Beyond low rank+sparse: multiscale low rank matrix decomposition,” IEEE J Sel Top Sig Proc, 10:672–687, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Deichmann R and Haase A, “Quantification of T1 values by SNAPSHOT-FLASH NMR imaging,” J Magn Res, 96:608–12, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Akcakaya M, Basha TA, Chan RH et al. , “Accelerated isotropic sub-millimeter whole-heart coronary MRI: compressed sensing versus parallel imaging,” Magn Reson Med, 71(2):815–822, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Sharma SD, Fong CL, Tzung BS et al. , “Clinical image quality assessment of accelerated magnetic resonance neuroimaging using compressed sensing,” Invest Radiol. Sep;48(9):638–45, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Manjon JV, Coupe P et al. , “Diffusion Weighted Image Denoising Using Overcomplete Local PCA,” PLOS ONE 8(9):e73021, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Candès EJ et al. , “Unbiased Risk Estimates for Singular Value Thresholding and Spectral Estimators,” IEEE TSP, 61:4643–57, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Veraart J, Novikov DS et al. , “Denoising of diffusion MRI using random matrix theory,” Neuroimage 142:3940–406, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]