Abstract

The opioid and polysubstance epidemics could drive a surge in new HIV infections among people who inject drugs (PWID). Longstanding strategies to reduce HIV incidence, including syringe service programs, condom distribution, medications for opioid use disorder, and low-barrier HIV testing and treatment have not been adequate to eliminate transmission in this population. Although HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is an evidence-based intervention that reduces HIV incidence among PWID, uptake in PWID has lagged due to limited PrEP knowledge, discrepancies between perceived and actual HIV risk, stigma, and structural barriers to adherence including homelessness and incarceration. In our efforts to deploy PrEP to PWID in our low-barrier substance use disorder bridge clinic, we have encountered another barrier: the HIV testing window period. We discuss challenges in delivering HIV exposure prophylaxis to the highest risk PWID, our current approach, and the need for more data to guide best practices.

Keywords: HIV prevention, PrEP, PEP, people who inject drugs, opioid use disorder, injection drug use

The current opioid and polysubstance use disorder epidemics, driven by illicitly manufactured fentanyl and stimulants that require frequent injection events, threaten a surge in HIV transmission among people who inject drugs (PWID), and recent outbreaks have been described in at least four states.1–4 Although HIV incidence among PWID has declined over recent decades, high rates of sexual and injection-related risk behaviors place PWID at substantial risk of HIV acquisition.5,6 Nearly 80% of U.S. PWID report past-year condomless sex or receptive syringe sharing, and 1 in 26 women and 1 in 42 men who inject drugs will contract HIV in their lifetime.7,8

Established strategies for preventing HIV transmission among PWID, including syringe service programs, condom distribution, low-barrier HIV testing and treatment, and medications for opioid use disorder have not proven adequate in preventing HIV outbreaks in this population. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with daily tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) is an evidence-based, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended strategy that reduces HIV incidence in those with sexual and/or injection-related risk.9,10 However, PrEP uptake among PWID lags behind that of other risk groups, due in part to low PrEP knowledge, discrepancies between perceived and actual HIV risk, provider stigma, and structural barriers such as poverty, homelessness, and incarceration.11,12 Developing strategies to deliver PrEP to PWID is an urgent priority.

In our low-barrier substance use disorder clinic, we care for many PWID meeting criteria for PrEP due to receptive syringe sharing and condomless sex with high-risk partners, including patients engaged in transactional sex and those experiencing sexual violence and trafficking. In our efforts to engage this population in PrEP, we have consistently encountered a barrier not well outlined in the literature: the HIV testing window period.

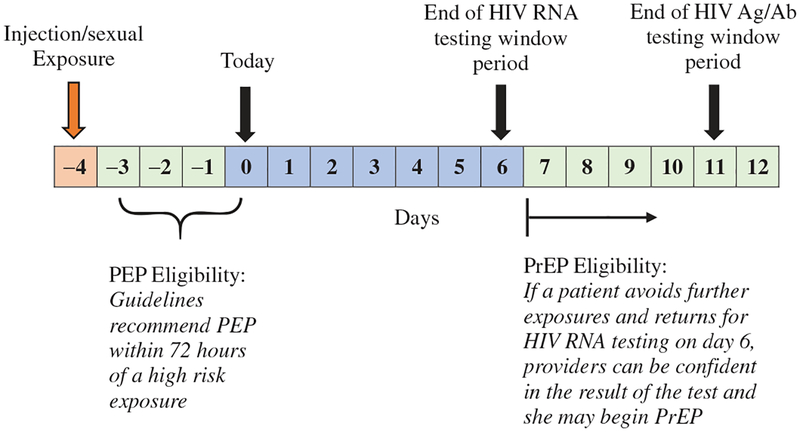

In order to mitigate the risk of viral resistance, guidelines require a negative HIV test before patients start PrEP.10 Added caution is required for patients who have had signs or symptoms of acute HIV, which include night sweats, diarrhea, and myalgias – symptoms that overlap with typical opioid withdrawal – in the past month. In these cases, the CDC outline three options: (1) document a negative HIV antigen/antibody (Ag/Ab) test and start PrEP immediately, (2) document a negative HIV RNA viral load and start PrEP immediately, and (3) defer PrEP decision and repeat testing in 1 month.10 Amidst current HIV outbreaks, a month is too long to wait. However, the first two options may not offer adequate reassurance for those with recent, high-risk exposures due to the HIV testing “window period,” the time between infection and test positivity. The window period is estimated to be 10–15 days for HIV RNA and 15–20 days for HIV Ag/Ab tests.13 If a patient presents, for example, four days after receptive syringe sharing, we would need to wait 6 more days until a negative HIV RNA test could be considered reliable, assuming they accrue no further exposures (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The HIV exposure prophylaxis eligibility and HIV testing window periods.

How, then, can PrEP be started safely in patients with very recent high-risk exposures? First, teams should consider eligibility for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), a 28-day course of three antiretroviral medications that reduce HIV incidence when started within 72 h of exposure.14 Unlike PrEP, PEP can be started as soon as labs are drawn because a three-drug regimen provides adequate HIV treatment in the event of unrecognized early HIV infection. At the end of the 28-day PEP course, patients who remain HIV-uninfected may be immediately transitioned to TDF/FTC alone for PrEP.14

Some of our most vulnerable patients, however, have exposures that fall outside PEP eligibility but inside the HIV testing window period (Figure 1), a situation that is not explicitly addressed by available guidelines. We have found that our providers, who are practicing amidst a current HIV outbreak in Boston, MA, are often wary of starting PrEP based on a negative Ag/Ab test in these cases. Given the social and structural vulnerabilities experienced by many PWID, their ability to avoid subsequent exposures and return for repeat testing before beginning PrEP is limited. Several times in our low-barrier clinic, we attempted the two-staged testing approach without success.

We have since adapted our practice for patients whose exposures fall outside of the typical PEP eligibility period but within the HIV testing window. Now, we discuss the risks and benefits of starting PEP beyond 72 h. Although PEP is most effective in preventing HIV within 72 h of exposure, the risks of starting PEP beyond 72 h are low. Patients who remain HIV negative are transitioned to PrEP at the end of 28 days. For patients with ongoing, high-risk exposures, “PEP-to-PrEP” may be the safest and most efficient way to prevent HIV, and it is an approach that has been well received by our patients and providers. Weekly or twice-weekly buprenorphine follow-up visits, which are typical in our low-barrier clinic, allow frequent check-ins to support PEP and PrEP adherence. Other strategies we are implementing to meet the needs of our patients include single tablet PEP regimens to reduce pill burden, prescriptions with weekly refills to reduce the impact of medication loss or theft, and intensive community-based navigation. Each of these approaches to broaden access merit formal evaluation as promising methods for PrEP to realize its public health potential and better benefit this socially marginalized population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Alison Rapoport and members of Boston University School of Medicine’s General Internal Medicine Writers’ Collaborative for their review of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health Bureau of Substance Addiction Services to develop Opioid Urgent Care Centers [RFR #163274] (Taylor, Walley) and by a National Institutes of Health Career Development Award [K01DA043412] (Bazzi).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors have no financial or other conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Cranston K. Notes from the field: HIV diagnoses among persons who inject drugs — Northeastern Massachusetts. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68:2015–2018. Available at: https://www-cdc-gov.ezproxy.bu.edu/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6810a6.htm. Accessed June 6 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Evans ME. Notes from the field: HIV infection investigation in a rural area — West Virginia, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:257–258. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6708a6.htm. Accessed August 5, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Peters PJ, Pontones P, Hoover KW, et al. HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(3):229–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Golden MR, Lechtenberg R, Glick SN, et al. Outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus infection among heterosexual persons who are living homeless and inject drugs – Seattle, Washington, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(15):344–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report. Vol. 29 2017. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published November 2018. Accessed October 3, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Burnett JC. HIV infection and HIV-associated behaviors among persons who inject drugs — 20 cities, United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:23–28. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6701a5.htm. Accessed July 31, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Spiller MW, Broz D, Wejnert C, Nerlander L, Paz-Bailey G. HIV infection and HIV-associated behaviors among persons who inject drugs — 20 cities, United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(10):270–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, Hall HI. Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(4):238–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States – 2017 update: a clinical practice guideline. 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Accessed August 5, 2019.

- [11].Bazzi AR, Biancarelli DL, Childs E, et al. Limited knowledge and mixed interest in pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among people who inject drugs. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(12):529–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Edelman EJ, Moore BA, Calabrese SK, et al. Primary care physicians’ willingness to prescribe HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis for people who inject drugs. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(4):1025–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Branson BM, Stekler JD. Detection of acute HIV infection: we can’t close the window. J Infect Dis. 2012;205(4):521–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated guidelines for antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV—United States, 2016. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68:335–338. [Google Scholar]