Abstract

Background:

Victims of dating violence experience suicidal ideation at a higher rate than the general population. However, very few studies have examined the relationship between dating violence and suicidal ideation within an empirically supported theory of suicide. The interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide posits that thwarted interpersonal needs (i.e., thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness) are proximal antecedents to suicidal ideation. The experience of dating violence may thwart such interpersonal needs, thus increasing risk for suicidal ideation.

Aims:

We aimed to examine the relationships among dating violence, thwarted interpersonal needs, and suicidal ideation and test the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide.

Method:

We conducted two cross-sectional studies on college students in dating relationships to examine these research questions.

Results:

Study 1 indicated positive correlations among dating violence (i.e., physical and psychological), thwarted belongingness, and perceived burdensomeness. Study 2 generally replicated the bivariate relationships of Study 1 and demonstrated that, at high levels of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness was correlated with suicidal ideation, while accounting for the effects of depressive symptoms and drug use.

Conclusion:

These results highlight the importance of using theory-guided research to understand the relationship between dating violence and suicidal ideation.

Keywords: intimate partner violence, partner abuse, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, suicidal ideation, interpersonal theory, physical assault, psychological aggression, dating violence

Suicidal ideation among college students is a precursor to suicide, a leading cause of death in young adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013). Thus, it is imperative to assess suicidal ideation and provide appropriate intervention. College students experience suicidal ideation at an alarmingly higher rate (10% in past month; Garlow et al., 2008) than the general population (3.7% in past year; Crosby, Han, Ortega, Parks, & Gfroerer, 2011). Identifying factors that facilitate the trajectory to suicidal ideation in college students is essential for improving suicide prevention efforts in this population.

Dating violence (DV) victimization, particularly physical assault and psychological aggression, is a well-documented risk factor for suicidal ideation in men and women (Afifi et al., 2009; Chan, Straus, Brownridge, Tiwari, & Leung, 2008; Devries et al., 2011; Golding, 1999; Heru, Stuart, & Recupero, 2007; Leone, 2011; Randle & Graham, 2011; Wolford-Clevenger & Smith, 2015; Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2015). Indeed, men and women who are victimized by DV exhibit elevated rates of suicidal ideation (17.6–68.7%; Golding, 1999; Pico-Alfonso et al., 2006; Schneider, Burnette, Ilgen, & Timko, 2009) compared with the general population (3.7%; Crosby et al., 2011). DV victimization is pervasive in college students, with 37% and 90% of college student relationships involving physical assault and psychological aggression, respectively (Shorey, Cornelius, & Bell, 2008). Yet, very few studies have examined the connection between DV victimization and suicidal ideation in college students. Furthermore, research on the relationship between DV victimization and suicidal ideation has been largely atheoretical. For example, a majority of the literature has identified psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, as explaining the high rates of suicidal ideation among DV victims (Chan et al., 2008; Iverson et al., 2012; Leiner, Compton, Houry, & Kaslow, 2008; Stein et al., 2010). Investigation of the DV–suicidal ideation connection guided by an empirically supported theory of suicide will aid in a more clinically useful understanding of suicide risk in college students.

The interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide (IPTS; Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010) offers an understanding of the relationship between DV victimization and suicidal ideation. According to the IPTS, suicidal ideation results from the product of feelings of liability and self-hatred (i.e., perceived burdensomeness) and feelings of loneliness and low reciprocal care (i.e., thwarted belongingness; Van Orden et al., 2010). The theory’s predictions about thwarted interpersonal needs interacting to predict suicidal ideation have been supported in clinical and nonclinical samples (Christensen, Batterham, Soubelet, & Mackinnon, 2013; Cukrowicz, Cheavens, Van Orden, Ragain, & Cook, 2011; Van Orden, Witte, Gordon, Bender, & Joiner, 2008). While the IPTS offers a potentially useful explanation for the relationship between DV victimization and suicidal ideation, the relationships among these constructs have yet to receive sufficient scrutiny (Van Orden et al., 2010).

Victims of DV may be at elevated risk for suicidal ideation owing to increased feelings of burdensomeness and disconnectedness. Psychological aggression involves verbal maltreatment, humiliation, and controlling tactics (Saltzman, Fanslow, McMahon, & Shelley, 2002), which have the potential to promote thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (Van Orden et al., 2010). Empirical data support this suggestion, demonstrating that psychological aggression impairs victims’ self-esteem and social support, increases depressive symptoms, and facilitates emotional and financial dependence on their violent partners (Davidson, Wingate, Grant, Judah, & Mills, 2011; Dutton & Goodman, 2005; Golding, 1999; Johnson & Leone, 2005). Such emotional, social, and financial damage may impact the degree of intimacy in the relationship (Heru et al., 2007) and increase victims’ feelings of loneliness, low reciprocal care, liability, and self-hatred.

Physical assault, involving behaviors such as hitting, punching, shoving, or harming one’s partner with an object, also conceivably increases feelings of burdensomeness and low belongingness (Saltzman et al., 2002; Van Orden et al., 2010). Physical assault can result in a number of physical health consequences (e.g., injuries) for which victims seek help for from law enforcement or health-care professionals (Campbell et al., 2002). Victims, especially men, may encounter unhelpful responses during help-seeking experiences, such as disbelief, apathy, minimization, victim-blaming attitudes, and being denied help (Douglas & Hines, 2011; Garimella, Plichta, Houseman, & Garzon, 2000; Stephens & Sinden, 2000). These experiences likely intensify victims’ feelings of liability, self-hatred, and disconnectedness from others. One study has supported this hypothesis, demonstrating that both physical assault and psychological aggression positively correlated with perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness in a college student sample (Lamis, Leenaars, Jahn, & Lester, 2013). This study further demonstrated that perceived burdensomeness, but not thwarted belongingness, predicted suicidal ideation while controlling for DV victimization and other risk factors (Lamis et al., 2013). However, the study did not test the main prediction of the IPTS: that thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness interact to predict suicide ideation. Further work is needed to test this critical tenet of the IPTS.

In sum, the literature regarding the connection between DV and suicidal ideation in college students is severely underdeveloped, and existing studies have typically examined this relationship from an atheoretical standpoint. The literature has suggested that physical assault and psychological aggression may result in mental health, physical health, and social and financial difficulties, which have potential to increase feelings of burdensomeness and disconnectedness (Campbell et al., 2002; Davidson et al., 2011; Douglas & Hines, 2011; Dutton & Goodman, 2005; Garimella et al., 2000; Golding, 1999; Stephens & Sinden, 2000). However, only one published study has examined the relationships among DV victimization, thwarted interpersonal needs, and suicidal ideation (i.e., Lamis et al., 2013). Additional theory-guided research is necessary to advance the understanding of the relationship between DV victimization and suicidal ideation, especially in college students. We conducted two studies examining the relationship between DV victimization and suicidal ideation among college students within the context of the IPTS.

Study 1

Aims and Hypotheses

Study 1 aimed to test the basic relationships among physical assault victimization, psychological aggression victimization, and thwarted interpersonal needs (i.e., perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness). We hypothesized that both forms of DV victimization would positively correlate with thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness.

Method

Participants

Undergraduate students (n = 502) volunteered for the study in exchange for research credit for an introduction to psychology course. Inclusion criteria were being 18 years of age or older and being in a dating relationship for at least 2 months. The sample was M = 18.80 years old (SD = 1.93), 65.7% female, and 76.1% freshmen. The race/ethnicity composition of the sample was as follows: White/Caucasian (81.2%), Black/African American (9.1%), Asian American (3.5%), Hispanic/Latino (2.1%), Indian/Middle Eastern (1.7%), Native American (0.8%), and “Other” (1.6%). The composition of the sample by family income level was as follows: less than US $50,000 (23.4%), $50,000–$100,000 (32.3%), $100,000–$150,000 (20.6%), $150,000–$200,000 (12.4%), greater than $200,000 (11.2%). A majority of the sample reported having a heterosexual orientation (95.6%) and not living with their partner (94.4%). The average relationship length was 14.37 months (SD = 14.55).

Procedure

The university’s Institutional Review Board approved the study procedures. Participants responded to an online battery of surveys. Given the sensitive nature of the items related to abuse and interpersonal problems within the survey, the last page of the survey displayed mental health resources including contact information for the first author in the event that any distress resulted from the study.

Measures

Demographics.

Demographic variables including age, gender, racial/ethnic identity, academic level, family income, and relationship characteristics were collected.

Dating Violence.

The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996; Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003) was used to measure physical assault and psychological aggression experienced by the respondent in their relationship within the past 12 months. The CTS2 is a 78-item measure that assesses the frequency (0 to more than 20 times) of relationship conflict tactics of negotiation, physical assault, psychological aggression, sexual coercion, and injury. Past studies have demonstrated the CTS2 to have good reliability and validity in various samples (Straus et al., 1996; Straus, Hamby, & Warren, 2003; Vega & O’Leary, 2007). The internal consistency for the subscales used in the current study ranged from questionable to good (psychological abuse victimization, α = 0.63; physical assault victimization, α = 0.79).

Interpersonal Needs.

The Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire (INQ; Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte, & Joiner, 2012) is a 15-item measure of perceptions of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness on 7-point Likert scale that ranges from not at all true for me to very true for me. The measure instructs participants to report on how they have been feeling recently. This measure has demonstrated convergent validity in samples of young and older adults (Van Orden et al., 2012). The subscales of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness have demonstrated excellent internal consistency in a prior undergraduate sample (αs = 0.90 and 0.92, respectively; Lamis et al., 2013) and good to excellent internal consistency in this sample (αs = 0.95 and .87, respectively).

Results and Discussion

See Table 1 for means and standard deviations of the original study variables. Original variables were used for descriptive statistics. Given that the DV and interpersonal needs variables exhibited positive skew, log transformations were performed on these variables prior to conducting t tests and correlational analyses.

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics for Study 1 and 2 measures

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thwarted belongingness | – | .44** | .05 | .16** | – | – | – | – |

| Perceived burdensomeness | .54** | – | .14** | .12** | – | – | – | – |

| Psychological aggression victimization | .18* | .28** | – | .42** | – | – | – | – |

| Physical assault victimization | .20* | .23** | .49** | – | – | – | – | – |

| Drug use | .07 | .17* | .26** | .15 | – | – | – | – |

| Alcohol use | .14 | .07 | 23** | .06 | .41** | – | – | – |

| Depressive symptoms | .58** | .45** | .08 | .14 | .20* | .19* | – | – |

| Suicidal ideation | .20* | .29** | .04 | .06 | .26* | .04 | 23** | – |

| Study 1 mean | 20.58 | 8.03 | 7.18 | 2.13 | – | – | – | – |

| (SD) | (11.36) | (4.96) | (13.13) | (9.32) | ||||

| Study 2 mean | 19.65 | 7.72 | 10.47 | 3.49 | 15.72 | 5.34 | 31.60 | 0.29 |

| (SD) | (10.97) | (4.15) | (17.91) | (15.87) | (3.84) | (4.90) | (8.90) | (1.06) |

Note. Above diagonal are correlations for Study 1, below diagonal are correlations for Study 2. SD = standard deviation.

p < .05.

p < .01 (two-tailed).

Twenty-three percent of the sample reported having experienced some level of physical assault in the past year. A majority of the sample (67%) reported having experienced some level of psychological aggression in the past year. To explore potential gender differences in DV victimization, thwarted belongingness, and perceived burdensomeness, we conducted t tests. Results indicated that men reported experiencing greater feelings of thwarted belongingness, M = 1.31, SD = 0.22, than women, M = 1.26, SD = 0.21, t(499) = 2.43, p = .015 (means and standard deviations are of the log-transformed variables). Men and women did not differ in perceived burdensomeness or DV victimization. Next, we computed Spearman’s rho correlations as our data are on an ordinal scale. Perceived burdensomeness was positively correlated with physical assault victimization and psychological aggression victimization (see Table 1). Thwarted belongingness was positively correlated with physical assault victimization but not with psychological aggression victimization.

In sum, bivariate results support that physical assault victimization is associated with increased feelings of burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, whereas psychological aggression victimization is associated with increased perceived burdensomeness, but not thwarted belongingness.

Study 2

Aims and Hypotheses

Study 2 aimed to replicate the basic relationships in Study 1: Perceived burdensomeness will positively correlate with physical assault and psychological aggression victimization, and thwarted belongingness will positively correlate with physical assault victimization. Study 2 also aimed to test, as posited by the IPTS, whether thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness interacted to predict suicidal ideation, such that, as perceived burdensomeness increases, the relationship between thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation strengthened. We hypothesized that this interaction would emerge while accounting for variables that exhibit bivariate correlations with suicidal ideation in the study (e.g., DV victimization, depressive symptoms, and alcohol and drug use; Garlow et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2004).

Method

Participants

Undergraduate students (n = 155) volunteered for the second study, also in exchange for research credit in an introduction to psychology course. Inclusion criteria were the same as Study 1 (i.e., 18 years of age or older and being in a dating relationship for at least 2 months). The sample was M = 19.76 years old (SD = 3.20), 57.8% female, and 51.7% freshmen. The race/ethnicity composition of the sample was as follows: White/Caucasian (74.8%), Black/African American (14.2%), Hispanic/Latino (2.6%), Asian American (1.3%), Indian/Middle Eastern (2.6%), Native American (0.6%), and “Other” (3.2%). The composition of the sample by family income level was as follows: less than US $50,000 (24.5%), $50,000–$100,000 (33.3%), $100,000–$150,000 (22.4%), $150,000–$200,000 (11.6%), greater than $200,000 (8.2%). A majority of the sample reported having a heterosexual orientation (97.3%) and not living with their partner (83.0%). The average relationship length was 15.20 months (SD = 17.42).

Procedure

The procedures for the second study were identical to the first study.

Measures

The same measures used in Study 1 were included in Study 2. The internal consistency coefficients for the subscales of the Conflict Tactics Scale-Revised ranged from questionable to good: psychological aggression victimization (α = 0.69); physical assault victimization (α = 0.84). Good internal consistency coefficients were demonstrated for the thwarted belongingness subscale (α = 0.87) and perceived burdensomeness subscale of the INQ (α = 0.90).

Depressive Symptoms.

The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) was used to assess depressive symptoms over the past week. The CES-D is a reliable and valid 20-item measure of depressive symptoms on a 4-point Likert scale from rarely/none of the time to most/all of the time (Radloff, 1977). The internal consistency for the CES-D in the sample of Study 2 was good (α = 0.86).

Alcohol Use.

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, de la Fuente, & Grant, 1993) is a 10-item questionnaire used to assess frequency, intensity, and negative consequences of alcohol use in the previous year. The AUDIT has demonstrated to be a reliable and valid measure of alcohol use (Reinert & Allen, 2007). The internal consistency for the AUDIT in the sample of Study 2 was good (α = 0.80).

Drug Use.

The Drug Use Disorders Identification (DUDIT; Stuart, Moore, Kahler, & Ramsey, 2003; Stuart, Moore, Ramsey, Kahler, 2004) is a 14-item questionnaire used to assess frequency and intensity of drug use in the previous year. The DUDIT assesses seven classes of drugs (e.g., stimulants). The DUDIT has demonstrated good reliability and validity (Stuart et al., 2008). The internal consistency for the DUDIT in the sample of Study 2 was acceptable (α = 0.74).

Suicidal Ideation.

Suicidal ideation was measured in Study 2 by the suicidality subscale of the Hopelessness Depression Symptom Questionnaire (HDSQ-SI; Metalsky & Joiner, 1997). The HDSQ-SI assesses suicidal ideation using four items measuring the frequency, planning aspects, controllability, and impulsive quality of suicidal ideation experienced over the past 2 weeks. Each item contains four statements ranging from 0 (absence of suicidal ideation) to 3 (high degree of suicidal ideation aspect being measured). The total score for the four items ranges from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating greater severity of suicidal ideation. The HDSQ-SI has demonstrated excellent internal consistency in a college sample (α = 0.96; Metalsky & Joiner, 1997) as well as in this second study’s sample (α = 0.94).

Results and Discussion

See Table 1 for means and standard deviations. Given the positive skew observed in the DV victimization, interpersonal needs, depressive symptoms, alcohol use, drug use, and suicidal ideation variables, log-transformations were performed prior to the t test, correlational, and regression analyses. Thirteen percent of the sample reported having experienced some level of physical assault in the past year. Forty-seven percent reported having experienced some level of psychological aggression in the past year. Ten percent of the sample reported having some level of suicidal ideation in the past 2 weeks. In an attempt to replicate the gender differences demonstrated in Study 1, we conducted t tests examining gender differences in DV victimization, thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation. Results indicated that men and women did not differ on these variables.

Next, we computed Spearman’s rho correlations to replicate the correlations demonstrated in Study 1. Perceived burdensomeness was correlated with depressive symptoms, physical assault victimization, and psychological aggression victimization. Thwarted belongingness was correlated with depressive symptoms, physical assault victimization, and psychological aggression victimization. Suicidal ideation was correlated with thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and drug use, but not DV victimization or alcohol use. See Table 1 for correlations for Study 2.

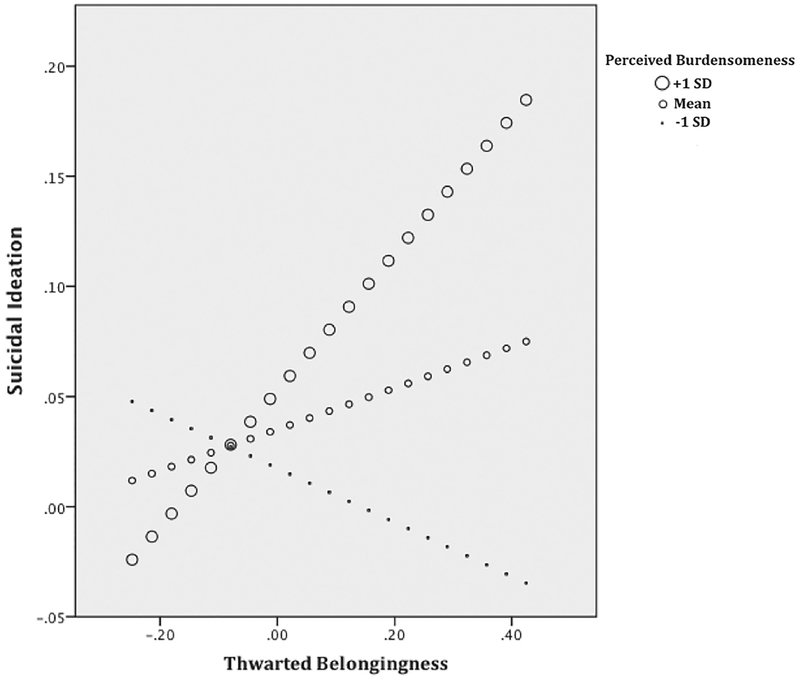

Next, we examined whether thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness interacted to predict suicidal ideation while controlling for the potential effects of depressive symptoms and drug use, as these were the sole bivariate correlates of suicidal ideation. We used Hayes & Matthes’s (2009) macro for testing interactions in SPSS. Suicidal ideation was entered as the criterion variable, thwarted belongingness as the focal predictor, and perceived burdensomeness as the moderating variable. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness were mean centered. The depressive symptoms and drug use subscales were entered as covariates. The overall model fit was significant, explaining 36% of the variance in suicidal ideation, R2 = .36, F(5,126) = 14.01, p < .001. The thwarted belongingness*perceived burdensomeness interaction term was significant, contributing a significant increase in R2, ΔR2 = .03, F = 5.67, p = .02 (see Table 2 for regression results. The interaction was probed at the mean, and 1 SD above and below the mean of perceived burdensomeness, which demonstrated that only at high levels of perceived burdensomeness was thwarted belongingness significantly associated with suicidal ideation. The associations of thwarted belongingness with suicidal ideation at low, average, and high levels of perceived burdensomeness are as follows: low (B = −0.13, p = .21), average (B = 0.09, p = .27), and high (B = 0.31, p = .03). See Figure 1 for a visual depiction of the interaction.

Table 2.

Study 2 results of regression predicting suicidal ideation

| Variable | B | t |

|---|---|---|

| Depressive symptoms | 0.0004 | 0.18 |

| Drug use | 0.73 | 3.71** |

| Thwarted belongingness | 0.09 | 0.27 |

| Perceived burdensomeness | 0.14 | 0.60 |

| Thwarted belongingness*perceived burdensomeness | 1.71 | 2.38* |

Note. Perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are mean centered.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Thwarted belongingness predicts suicidal ideation at high levels of perceived burdensomeness.

Results from Study 2 generally supported the bivariate relationships found in Study 1, lending further support that physical assault and psychological aggression victimization may increase perceived burdensomeness and feelings of disconnectedness. We were unable to replicate the finding that men experienced greater levels of thwarted belongingness; this may be due to the small sample size and consequently lower statistical power. Results supported the IPTS position that suicidal ideation results as a product of thwarted interpersonal needs; only at high levels of perceived burdensomeness was thwarted belongingness associated with suicidal ideation.

General Discussion

The current studies are among the first to investigate the well-documented relationship between DV victimization and suicidal ideation within the framework of the IPTS (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). Study 1 demonstrated that physical assault and psychological aggression victimization were associated with increases in perceived burdensomeness, whereas solely physical assault victimization was associated with increases in thwarted belongingness. Study 2 generally replicated these findings but found psychological aggression victimization to correlate with thwarted belongingness. Study 2 also supported the IPTS tenet that only at high levels of perceived burdensomeness was thwarted belongingness associated with suicidal ideation, while accounting for depressive symptoms and drug use.

Although Study 2 did not replicate the well-supported relationship between DV and suicidal ideation (e.g., Afifi et al., 2009; Devries et al., 2011; Golding, 1999), Study 1 and Study 2 replicated associations between DV and thwarted interpersonal needs that are indicative of suicidal desire (Lamis et al., 2013; Van Orden et al., 2008). Psychological aggression may facilitate feelings of self-hatred and liability owing to its effects on victims’ self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and emotional and financial dependence on their violent partners (Davidson et al., 2011; Golding, 1999; Johnson & Leone, 2005). Psychological aggression was not associated with increases in thwarted belongingness in Study 1 but was associated with increases in thwarted belongingness in Study 2. This finding may be due to our measurement of psychological aggression being more reliable in Study 2.

Physical assault victimization, however, was associated with both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness in each study. Although the current studies did not examine potential mechanisms underlying this association, we speculate that victims may feel like a burden on their perpetrator in order to explain the violence. That is, victims may blame themselves for the violence, which increases their sense of burdensomeness. For example, victims may believe that if they were not such a burden or difficult to care for, they would not experience DV. Finally, another explanation for the relationship between thwarted interpersonal needs and DV is that individuals who feel like a burden on or disconnected from others may be vulnerable to entering relationships with violent partners. Further research is needed to explicate these findings.

Finally, Study 2 demonstrated that at high levels of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness was associated with suicidal ideation while controlling for depressive symptoms and drug use. This finding partially supported our hypothesis and past findings (e.g., Van Orden et al., 2008), as well as a past study finding perceived burdensomeness, but not thwarted belongingness, to predict suicidal ideation in a college student sample (Lamis et al., 2013). Taken together, these findings suggest that perceived burdensomeness may play a crucial role in the development of suicidal ideation in college students. Perhaps college students place much importance on independence and pride given the stage in their life of developing autonomy and are therefore much more affected by events that would heighten perceptions of liability and self-loathing. Future work should examine potential explanations for the salience of perceived burdensomeness in relation to suicidal ideation in this population.

Limitations and Future Directions

The studies have limitations that future research may improve upon. First, the studies were of cross-sectional design. Longitudinal studies will help inform whether DV precedes thwarted interpersonal needs or if thwarted interpersonal needs predispose individuals to violent relationships. Furthermore, longitudinal studies will specify if thwarted interpersonal needs increase suicidal ideation, if suicidal ideation predisposes individuals to interpersonal problems, or if there is a reciprocal relationship. Second, the CTS-2 psychological aggression subscale does not include controlling violence items. Controlling violence may be a subtype of psychological aggression that is more associated with suicidal ideation (Wolford-Clevenger & Smith, 2015). Future work should consider using measures that assess each facet of psychological aggression, including verbal abuse and coercive control (Saltzman et al., 2002). Third, the current study did not assess sexual violence in intimate relationships, an important aspect of DV that deserves future attention. Fourth, the current study did not test whether the combined or unique effects of physical assault and psychological aggression are most influential in developing suicide risk. Fifth, Study 2 had a relatively small sample size, which likely limited its statistical power. Finally, the study investigated violence among primarily heterosexual college students in dating relationships. Future studies should replicate these findings in samples of cohabitating/married and/or same-sex couples experiencing intimate partner violence. Future work with larger samples will be able to statistically control for more variables that are associated with increased suicidal ideation in order to further evaluate the unique relations between thwarted interpersonal needs and suicidal ideation.

Clinical Implications

Despite these limitations, these studies’ findings provide some tentative clinical implications. First, the finding in Study 2 that 10% of the sample experienced suicidal ideation in the past 2 weeks suggests that suicidal ideation is a significant concern for college students. University student health and counseling centers should implement routine suicide risk assessments in their intake procedures in order to prevent suicidal ideation from developing into suicidal behaviors. Campus-wide initiatives to reduce college students’ risk for suicide have been pilot-tested and recommended in detail elsewhere (Kaslow et al., 2012). In particular, feelings of burdensomeness and disconnectedness appear to be important targets for suicide risk reduction among college students. Suicide prevention programs on college campuses may implement methods to increase college students’ feelings of autonomy while also fostering their sense of social connectedness. Finally, given that psychological aggression and physical assault were associated with thwarted interpersonal needs that are indicative of suicidal desire, clinicians should inquire about such experiences and attend to potential suicide risk.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grant K24AA019707 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) awarded to the last author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

About the authors

Caitlin Wolford-Clevenger, MS, is pursuing her PhD in Clinical Psychology at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, TN. She received her BA and MS in Psychology at the University of South Alabama. Her research interests focus on understanding and preventing self- and other-directed aggression.

JoAnna Elmquist, BA, is a doctoral student in clinical psychology at the University of Tennessee, TN. She received her BA from Trinity University. Her research interests focus on family violence across the lifespan, including intimate partner violence and child maltreatment.

Meagan J. Brem, MA, is a clinical psychology doctoral student at the University of Tennessee, TN. She received her BA from Southwestern University and her MA from Midwestern State University. Her research interests include risk and protective factors for intimate partner violence, including jealousy, mindfulness, and cyber abuse.

Heather Zapor, BA, is a doctoral student in clinical psychology at the University of Tennessee, TN. She received her BA from the University of Akron. Her research interests include risk and resilience factors for intimate partner violence.

Gregory L. Stuart, PhD, is Professor of Clinical Psychology at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville, TN, and Director of Family Violence Research at Butler Hospital. He is also an adjunct professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, RI.

References

- Afifi T, MacMillan H, Cox B, Asmundson G, Stein M, & Sareen J (2009). Mental health correlates of intimate partner violence in marital relationships in a nationally representative sample of men and women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 1398–1417. doi: 10.1177/0886260508322192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, Kub J, Schollenberger J, O’Campo P, … Wynne C (2002). Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Archives of Internal Medicine, 162(10), 1157–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. (2013). Injury. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/injury [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, Straus MA, Brownridge DA, Tiwari A, & Leung WC (2008). Prevalence of dating partner violence and suicidal ideation among men and woman university students worldwide. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, 53, 529–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Batterham PJ, Soubelet A, & Mackinnon AJ (2013). A test of the interpersonal theory of suicide in a large community-based cohort. Journal of Affective Disorders, 144(3), 225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby AE, Han B, Ortega LAG, Parks SE, & Gfroerer J (2011). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among adults aged >18 years – United States 2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60(SS12), 1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cukrowicz KC, Cheavens JS, Van Orden KA, Ragain RM, & Cook RL (2011). Perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation in older adults. Psychology and Aging, 26(2), 331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson CL, Wingate LR, Grant DM, Judah MR, & Mills AC (2011). Interpersonal suicide risk and ideation: The influence of depression and social anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30(8), 842–855. [Google Scholar]

- Devries K, Watts C, Yoshihama M, Kiss L, Schraiber L, Deyessa N, … Garcia-Moreno C (2011). Violence against women is strongly associated with suicide attempts: Evidence from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence against women. Social Science & Medicine, 73(1), 79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas E, & Hines D (2011). The helpseeking experiences of men who sustain intimate partner violence: An overlooked population and implications for practice. Journal of Family Violence, 26, 473–485. doi: 10.1007/s10896-011-9382-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, & Goodman LA (2005). Coercion in intimate partner violence: Toward a new conceptualization. Sex Roles, 52(11–12), 743–756. [Google Scholar]

- Garimella R, Plichta SB, Houseman C, & Garzon L (2000). Physician beliefs about victims of spouse abuse and about the physician role. Journal of Women’s Health & Gender-Based Medicine, 9(4), 405–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garlow SJ, Rosenberg J, Moore JD, Haas AP, Koestner B, Hendin H, & Nemeroff CB (2008). Depression, desperation, and suicidal ideation in college students: Results from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention College Screening Project at Emory University. Depression and Anxiety, 25(6), 482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding JM (1999). Intimate partner violence as a risk factor for mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Family Violence, 14(2), 99–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, & Matthes J (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41(3), 924–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heru AM, Stuart GL, & Recupero PR (2007). Family functioning in suicidal inpatients with intimate partner violence. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 9(6), 413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iverson KM, Dick A, McLaughlin KA, Smith BN, Bell ME, Gerber MR, … Mitchell KS (2012). Exposure to interpersonal violence and its associations with psychiatric morbidity in a U.S. National Sample: A gender comparison. Psychology of Violence. doi: 10.1037/a0030956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, & Leone JM (2005). The differential effects of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 322–349. doi: 10.1177/0192513X04270345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE Jr. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Garcia-Williams A, Moffitt L, McLeod M, Zesiger H, Ammirati R, … Emory Cares 4 U Coalition, M. O. T. (2012). Building and maintaining an effective campus-wide coalition for suicide prevention. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 26(2), 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Lamis DA, Leenaars LS, Jahn DR, & Lester D (2013). Intimate partner violence: Are perpetrators also victims and are they more likely to experience suicide ideation? Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 28(16), 3109–3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiner AS, Compton MT, Houry D, & Kaslow NJ (2008). Intimate partner violence, psychological distress, and suicidality: A path model using data from African American women seeking care in an urban emergency department. Journal of Family Violence, 23(6), 473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Leone JM (2011). Suicidal behavior among low-income, African American woman victims of intimate terrorism and situational couple violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26, 2568–2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metalsky GI, & Joiner JE (1997). The Hopelessness Depression Symptom Questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 21(3), 359–384. [Google Scholar]

- Pico-Alfonso M, Garcia-Linares M, Celda-Navarro N, Blasco-Ros C, Echeburua E, & Martinez M (2006). The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women’s mental health: Depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. Journal of Women’s Health, 15(5), 599–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Randle AA, & Graham CA (2011). A review of the evidence on the effects of intimate partner violence on men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 12(2), 97–111. doi: 10.1037/a0021944 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert DF & Allen JP (2007). The alcohol use disorders identification test: An update of research findings. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(2), 185–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM, & Shelley GA (2002). Intimate partner violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements, version 1.0 Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, & Grant M (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption – II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider R, Burnette ML, Ilgen MA, & Timko C (2009). Prevalence and correlates of intimate partner violence victimization among men and women entering substance use disorder treatment. Violence & Victims, 24(6), 744–756. doi: 10.1891/0886-6708.24.6.744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey RC, Cornelius TL, & Bell KM (2008). A critical review of theoretical frameworks for dating violence: Comparing the dating and marital fields. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 13(3), 185–194. [Google Scholar]

- Stein DJ, Chiu WT, Hwang I, Kessler RC, Sampson N, Alonso J, … Nock MK (2010). Cross-national analysis of the associations between traumatic events and suicidal behavior: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PloS One, 5(5), e10574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens BJ, & Sinden PG (2000). Victims’ voices domestic assault victims’ perceptions of police demeanor. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15(5), 534–547. [Google Scholar]

- Straus M, Hamby S, Boney-McCoy S, & Sugarman D (1996). The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17, 283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, & Warren WL (2003). The Conflict Tactics Scales handbook. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Moore TM, Kahler CW, & Ramsey SE (2003). Substance abuse and relationship violence among men court-referred to batterers’ intervention programs. Substance Abuse, 24, 107–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Moore TM, Ramsey SE, & Kahler CW (2004). Hazardous drinking and relationship violence perpetration and victimization in women arrested for domestic violence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65, 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart GL, Temple JR, Follansbee K, Bucossi MM, Hellmuth JC, & Moore TM (2008). The role of drug use in a conceptual model of intimate partner violence in men and women arrested for domestic violence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22, 12–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, & Joiner TE Jr (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, & Joiner TE Jr. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117, 575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Gordon KH, Bender TW, & Joiner TE Jr. (2008). Suicidal desire and the capability for suicide: Tests of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior among adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega E, & O’Leary KK (2007). Test–retest reliability of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2). Journal of Family Violence, 22(8), 703–708. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9118-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolford-Clevenger C, Febres J, Elmquist J, Zapor H, Brasfield H, & Stuart GL (2015). Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among court-referred male perpetrators of intimate partner violence. Psychological Services, 12(1), 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolford-Clevenger C, & Smith PN (2015). A theory-based approach to understanding suicide risk in shelter-seeking women. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 16(2), 169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Hoven CW, Liu X, Cohen P, Fuller CJ, & Shaffer D (2004). Substance use, suicidal ideation and attempts in children and adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34(4), 408–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]