Abstract

We report on a former 28-week gestation neonate with persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) endocarditis, with a heterozygous Factor V Leiden mutation. The neonate became clinically ill after 1 week of life, with positive blood cultures for MRSA. Echocardiography revealed large thrombi in the inferior vena cava and right atrium. Bacteremia persisted despite removal of umbilical arterial and venous catheters and empiric administration of therapeutic doses of vancomycin (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] 2 mg/L) and ceftazidime. To narrow therapy, ceftazidime was discontinued, while gentamicin and rifampin were added. Cultures remained positive and, therefore, linezolid was added, and subsequent blood cultures became negative. Since prolonged linezolid use of 2 weeks or longer carries potential adverse effects, antibiotics were changed to daptomycin, which is bactericidal and recommended for treatment of invasive MRSA infections when vancomycin MICs are ≥2 mg/L to minimize vancomycin treatment failure.

Enoxaparin was initiated, with anti-Xa assay monitoring. A workup for thrombophilia revealed heterozygous Factor V Leiden mutation. Serial echocardiograms demonstrated decreasing size of the thrombi, which were no longer visualized at 2 months of age. Creatinine kinase remained normal. The infant had no seizures on daptomycin. The management of persistent MRSA bacteremia in neonates associated with a large thrombus poses a unique challenge due to the long duration of treatment.

To our knowledge, this is the first case of prolonged and safe daptomycin and enoxaparin use in a preterm neonate. Daptomycin may be considered in cases of clinical failure with vancomycin when a lengthy treatment course is contemplated.

Keywords: daptomycin, endovascular infection, enoxaparin, MRSA, neonate

Background

Premature neonates are at increased risk for thromboembolic events because of the unique factors associated with thrombosis and complex medical care in the neonatal intensive care unit.1 Intracardiac thrombi in newborns are becoming more prevalent with increased use of umbilical venous catheters (UVCs) and peripheral inserted central catheters.2 Several management options, largely extrapolated from adult literature, exist, including expectant management, nitroglycerin ointment, thrombolytic therapy, anticoagulant therapy, and surgery.3 Multiple case reports4–6 of intravascular thrombosis in preterm infants describe successful treatment with anticoagulants, enoxaparin, and recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, along with different combinations of antibiotics.

Infective endocarditis is a major complication of indwelling venous catheters. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has become a frequent source of infections in premature and critically ill neonates and is associated with high morbidity.7 Vancomycin is the primary treatment for invasive and endovascular MRSA infections in neonates, but clinical failure is common if the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) is >2 mg/L. The US Food and Drug Administration currently does not approve clindamycin and linezolid for treatment of invasive and endovascular MRSA infections in neonates. Clindamycin is a bacteriostatic agent, and long-term use of linezolid has side effects such as myelosuppression and elevation of liver enzymes, limiting their long-term use in neonates. The Infectious Diseases Society of America suggests daptomycin as an alternative treatment for MRSA endovascular infection, but it is not approved for use in pediatric patients less than 1 year of age by the US Food and Drug Administration.8,9

Daptomycin is a cyclic lipopeptide antimicrobial agent not routinely used in neonates because of a scarcity of literature on its efficacy and safety in infants. There are some case reports10–12 in which daptomycin is used in neonates, but none involving a high dose of 6 mg/kg/dose, frequency interval of every 12 hours, and long duration of use. We present the first case of prolonged (40 days) and high-dose (6 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours) daptomycin and prolonged enoxaparin use in a neonate for the treatment of infected intravascular thrombi.

Case

The patient was a 28-week, 1-day–old female infant with a birth weight of 1050 g born via repeat cesarean section. Prenatal laboratory tests for human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, rubella, varicella, and Group B Streptococcus were all negative. At birth, a UVC and an umbilical arterial catheter were placed for central access. On the first day of life (DOL) ampicillin (100 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours) and gentamicin (5 mg/kg/dose every 48 hours) were initiated. Initial blood cultures were negative for 48 hours, and ampicillin and gentamicin were discontinued on DOL 2.

On DOL 8, the patient had several bradycardic and desaturation events that necessitated a full sepsis workup, including blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cultures. Laboratory tests showed white blood cells (WBCs) of 17,900 cells/μL, with a hematocrit of 28.4% and platelets of 219 K/μL. C-reactive protein was elevated at 69.99 mg/dL. The CSF analysis showed WBCs of 19 cell/μL, red blood cells of 31 cells/μL, glucose of 70 mg/dL, and a protein of 93 mg/dL, while the CSF cultures had no growth. The UVC and umbilical arterial catheter were removed. Intravenous (IV) vancomycin (15 mg/kg/dose every 18 hours) and IV ceftazidime (30 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours) were started empirically. Ceftazidime was selected over cefotaxime because of a nationwide shortage due to the discontinuation of cefotaxime. On DOL 10, blood cultures grew MRSA that was sensitive to daptomycin (MIC 1), doxycycline (MIC 1), gentamicin (MIC < 1), linezolid (MIC 4), quinupristin and dalfopristin (Synercid) (MIC 4), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (MIC < 0.5/9.5), and vancomycin (MIC 2). Ceftazidime was discontinued on DOL 10, and IV rifampin (10 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours) was added for synergistic effect.

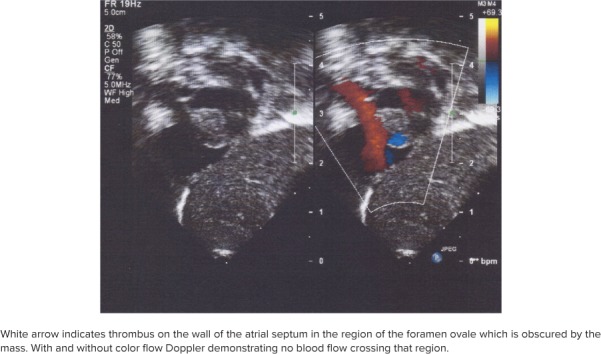

The vancomycin serum trough concentration before the third dose was subtherapeutic at 7.5 mg/L, with a goal range for the trough concentration of 15 to 20 mg/L. A repeat concentration on 15 mg/kg/dose every 8 hours was 13.1 mg/L. One dose of gentamicin (4 mg/kg/dose every 36 hours) was added on DOL 11 as an adjunct dose. Repeat culture also grew MRSA on DOL 12. Further evaluation included a head and renal ultrasounds and an echocardiogram. The echocardiogram revealed 2 large thrombi, one in the inferior vena cava, described as “a 3-mm echogenic focus,” and a second finding in the atrial septum region of the patent foramen ovale, noted to be “a large mass consistent with thrombus” (Figure 1). A hematological evaluation showed normal concentrations of fibrinogen (588 mg/dL), anti-thrombin III (59 [69%–138%]), protein C (21 [66%–128%]), and protein S (46 [45%–139%]). Coagulation panels showed a prothrombin time of 11.9 seconds [9.7–12.4 seconds], a partial thromboplastin time of 21.1 seconds [25–37 seconds], and an international normalized ratio of 1.08 [0.9–1.2].

Figure 1.

Echocardiogram from December 15, 2017.

On DOL 13, vancomycin steady-state trough concentration was 16 mg/L. Blood cultures continued to grow MRSA, so linezolid (10 mg/kg/dose every 8 hours) was substituted for rifampin. The first sterile blood culture was noted on DOL 14. As a result of the presence of infected MRSA thrombi, treatment course was anticipated to be 4 to 6 weeks. Use of linezolid for >2 weeks has been associated with serious side effects (e.g., lactic acidosis, myelosuppression, peripheral and optic neuropathy), and cultures grew MRSA despite a therapeutic vancomycin trough concentration with a MIC of 2.13,14 Therefore, both vancomycin and linezolid were discontinued and daptomycin (6 mg/kg every 12 hours; Table 1) was started on DOL 15.15–17

Table 1.

Daptomycin Dosing, Pharmacokinetics, and Adverse Effects

| Parameter | Daptomycin |

|---|---|

| Dose and interval | 6 mg/kg/dose every 12 hr infused over 60 min* |

| Serum daptomycin concentrations, mg/L | 33.2 (peak), 3.17 (trough) |

| AUC, mg x h/L | 157.5 |

| MIC, mg/L | 1 |

| Half-life, hr | 3 |

| Volume of distribution, L/kg | 0.27 |

| Clearance, L/hr/kg | 0.06 |

| Adverse effects | No seizures |

| CPK 84–200 units/mL |

CPK, creatine phosphokinase; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; NS, normal saline

* Diluted in NS for 10 mg/mL.

Blood cultures remained negative on DOLs 15 and 16. Weekly creatine phosphokinase values remained normal (84–200 international units/L), and the neonate had no seizure-like activity. After 2 weeks of treatment with daptomycin alone, the decision was made to continue treatment for a total of 6 weeks or until the thrombi improved, despite the lack of previous literature.15 On DOL 27, daptomycin serum concentrations were drawn in collaboration with Center for Anti-Infective Research and Development at Hartford Hospital. Concentrations collected 1 hour after administration of the morning IV push dose (peak), 10 hours later, and 1 hour before the next dose (trough) allowed for determination of the area under the curve.

In combination with daptomycin, enoxaparin was started at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours. Enoxaparin comes fabricated in 100 mg/mL solutions, which we diluted to 1 unit/1 mg.18 Tuberculin syringes were used to measure and administer the doses. Dosage adjustments were difficult because they could only be made in 1 unit/1 mg increments. Anti-Xa concentrations were checked 4 hours after administration (Table 2). Initially, anti-Xa values were 0.01 units/mL and 0.0 units/mL (therapeutic was 0.5–1.0 units/mL). In consultation with several pediatric hematologists outside of our institution, the pediatric hematology/oncology consulting attending recommended increasing enoxaparin to 2 mg/kg/dose. Medications continued to be weight-adjusted once a week to account for growth and weight gain. However, the patient proved to be sensitive to the changes in enoxaparin dosages, with small increases in dosages causing the anti-Xa assay to be above or below the desired threshold. Even with the anti-Xa concentrations outside of the desired range, the thrombi continued to shrink.

Table 2.

Enoxaparin Dosing and Corresponding Anti-Xa Level

| DOL | Weight (kg) | Enoxaparin Dosage* | Corresponding Anti-Xa Concentration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intended, mg/dose | Actual, mg (mL) | mg/kg/dose | |||

| 12 | 1.05 | 1.6 | 2 (0.02) | 1.9 | 0 |

| 13 | 1.04 | 1.7 | 2 (0.02) | 1.92 | 0.01 |

| 14 | 1.05 | 2 | 2 (0.02) | 1.9 | 0.23 |

| 15 | 1.08 | 2.5 | 3 (0.03) | 2.78 | 0.77 |

| 26 | 1.23 | 3 | 3 (0.03) | 2.44 | Not obtained |

| 33 | 1.47 | 3.6 | 4 (0.04) | 2.72 | 0.05 |

| 38 | 1.575 | 4 | 4 (0.04) | 2.54 | 0.46 |

| 39 AM | 1.64 | 5 | 5 (0.05) | 2.74 | Not obtained |

| 39 PM | 1.64 | 4 | 4 (0.05) | 2.74 | 0.54 |

| 42 | 1.775 | 5.3 | 5 (0.05) | 2.82 | 0.4 |

| 45 AM | 1.855 | 5.3 | 5 (0.05) | 2.96 | Not obtained |

| 45 PM | 1.855 | 6 | 6 (0.06) | 2.96 | 0.21 |

| 46 AM | 1.865 | 6 | 6 (0.06) | 3.49 | Not obtained |

| 46 PM | 1.865 | 7 | 7 (0.07) | 3.49 | 0.48 |

| 55 AM | 2.18 | 7 | 7 (0.07) | 3.21 | Not obtained |

| 55 PM | 2.18 | 7 | 7 (0.07) | 3.21 | 0.49 |

| 61 | 2.475 | 7 | 7 (0.07) | 2.83 | Not obtained |

* All patients received enoxaparin every 12 hours.

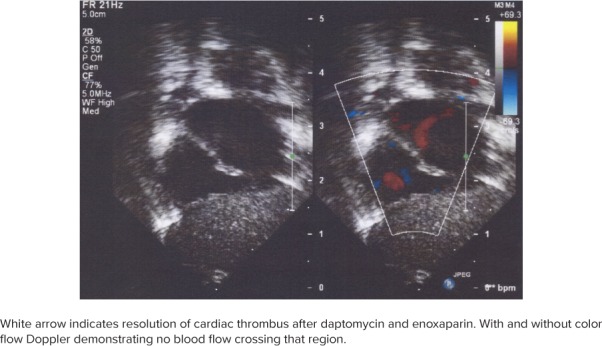

By DOL 33, the thrombus in the inferior vena cava had resolved and no longer registered on abdominal ultrasound (Figure 2). On DOL 54, the thrombus in the right atrium no longer appeared on echocardiogram. Daptomycin was discontinued on DOL 55 after a 6-week course from the first negative blood culture. On DOL 68, enoxaparin was discontinued, 2 weeks after the thrombi had resolved on ultrasound. On DOL 82, the patient was discharged home in the care of her parents. On a follow-up visit 6 months later she continued to grow and achieved her developmental milestones appropriately.

Figure 2.

Echocardiogram from January 5, 2018.

Discussion

MRSA-infected thrombi in neonates pose the challenge of long-term treatment with an antibiotic and anticoagulant combination therapy. Our case provides solace to providers faced with such management dilemmas. To our knowledge, this is the first case of MRSA-infected thrombi successfully treated with prolonged daptomycin (>2 weeks) and enoxaparin at larger doses (6 mg/kg/dose).

Daptomycin. MRSA bacteremia is associated with high morbidity and mortality and is likely to continue to affect neonates and children for the foreseeable future. The epidemiology of MRSA has considerably evolved over the past 65 years. In the neonatal intensive care unit the prevalence rates have been reported19–22 as <1% to 8.6%. A study23 from 2010 in the United Kingdom and Ireland showed that 61% of pediatric MRSA bacteremic cases occurred in children under the age of 1 year and that 35% of those cases occurred during the neonatal period.

In our case, MRSA bacteremia persisted despite therapeutic doses of vancomycin. Such clinical failures are reported with MIC > 2 mg/L. Likely explanations are 1) bacteriostatic effect, 2) inadequate antibiotic concentrations in tissue and/or thrombus. In addition, a longer treatment requires frequent monitoring of van-comycin trough concentrations. Linezolid was able to eliminate the MRSA bacteremia, but use for >2 weeks is associated with side effects, notably lactic acidosis, myelosuppression, abnormal liver, and peripheral and optic neuropathy.13,14 In this situation, daptomycin was considered because of a more favorable side effect profile of elevated creatinine kinase and possible seizures. Creatine phosphokinase values remained normal, and no seizure activity was seen.

Daptomycin has been effective in treating MRSA bacteremia, endocarditis, and skin and soft tissue infections.15 The efficacy of daptomycin is probable in treating children, and especially neonates, but there have been no large-scale clinical trials to support this assertion. It is not commonly considered as a treatment option for invasive endovascular neonatal infections. Adverse effects in neonatal canine models within the musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, and nervous systems were observed.9,10,24,25 There are numerous studies that indicate the potential for the benefits and relative safety of daptomycin use in children and neonates. An analysis of 128 children treated in Greece between 2007 and 2016 showed that daptomycin (10 mg/kg daily), alone or in combination, was effective at treating invasive and non-invasive musculoskeletal, skin, and soft tissue infections with no clinically significant adverse effects requiring premature discontinuation of treatment.26

Several neonatal cases have shown uncomplicated courses of 14 days of daptomycin.27,28 A 1-month-old, former 24-week gestation neonate with persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis bacteremia and impaired renal function showed efficacy with 6 mg/kg IV every 12 hours without any adverse events.10 A retrospective study28 demonstrated the wide range in dosage and treatment length for a variety of ailments ranging from bacteremia to osteomyelitis and to septic arthritis, indicating both the therapeutic value of daptomycin in the pediatric population and a need for further research to refine treatment parameters. Daptomycin serum concentrations in our case were similar to the previously reported area under the curve of 157 (Table 1).17,29

Enoxaparin. Extremely premature infants represent a special at-risk population for thromboembolic events as a result of increased prothrombic activity, relatively low amounts of anticoagulants, and various imbalances in the physiologic fibrinolytic system.1 While the complications are agreed upon, such as right-sided heart failure, arrhythmia, pulmonary embolus, and respiratory distress, no clear guidelines exist for the treatment of such conditions in preterm infants with very low birth weight.1 One option is a thrombectomy, but the unstable status of our patient and her low weight precluded surgery as a viable option. The catheter, the nidus for the infection, was removed, and enoxaparin was added for anticoagulation.

In addition, our patient was diagnosed with a Factor V Leiden heterozygote mutation at 4 weeks of life, but not with a prothrombin G20210A mutation. Factor V Leiden, as well as other congenital thrombophilic conditions, plays a large role in thrombus formation in neonates, but it should not be the seen as the sole contributing factor. A study in The Netherlands30 showed that while almost all children with venous thromboembolic disease have thrombophilic risk factors, only 5% of children with thrombophilic risk factors have venous thromboembolic disease. In this patient, the thrombus appears to be directly related to the central catheter.

Monagle et al31 developed guidelines for antithrombic therapy in neonates and children using data from adult and pediatric studies. Additionally, a 2016 Cochrane review3 neither supported nor opposed the current guidelines as a result of the lack of any large-scale double-blind clinical study. The 2 thrombi decreased in size over time despite having a mean anti-Xa value of 0.415. This would suggest that the clinically effective concentration may be lower than the purported therapeutic guidelines.32 This confirms the findings in several case reports and single-center studies,4,33 which found recommended dosing of 1.5 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours to be inadequate to achieve desired therapeutic response. The dosage for our patient began at 2 mg/kg every 12 hours and was increased to a high of 3.49 mg/kg every 12 hours. A dose larger than the guidelines was tolerable in this case and was necessary to achieve therapeutic results. Further investigation will be necessary to ascertain if larger doses of enoxaparin are tolerable and necessary to achieve the desired therapeutic effect.

Conclusion

MRSA-infected thrombi secondary to central venous catheters in premature neonates require lengthy treatment with antibiotics and anticoagulants. Daptomycin offers an alternative option in situations of clinical failure due to vancomycin, and it was found to be safe and effective in our case. Concomitant use of an enoxaparin, despite subtherapeutic concentrations, seems to be effective in the resolution of infected thrombi.

Acknowledgments

We thank David P. Nicolau, PharmD, FCCP, FIDSA, Director, and the Center for Anti-Infective Research and Development for obtaining the daptomycin concentrations. We acknowledge Drs Igal Fligman and Donna Better from the Department of Pediatrics, NYU Winthrop, for their expert opinion and echocardiogram pictures.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AUC

area under the curve

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- DOL

day of life

- IV

intravenous

- MIC

minimum inhibitory concentration

- MRSA

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- UVC

umbilical venous catheter

- WBC

white blood cell

Footnotes

Disclosure The authors declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria. The authors had full access to all patient information in this report and take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rimensberger PC, Humbert JR, Beghetti M. Management of preterm infants with intracardiac thrombi: use of thrombolytic agents. Paediatr Drugs. 2001;3(12):883–898. doi: 10.2165/00128072-200103120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.García-Teresa MA, Casado-Flores J, Delgado Domínguez MA et al. Infectious complications of percutaneous central venous catheterization in pediatric patients: a Spanish multicenter study. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(3):466–476. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romantsik O, Bruschettini M, Zappettini S et al. Heparin for the treatment of thrombosis in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012185.pub2. CD012185. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012185.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chander A, Nagel K, Wiernikowski J et al. Evaluation of the use of low-molecular-weight heparin in neonates: a retrospective, single-center study. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2013;19(5):488–493. doi: 10.1177/1076029613480557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrari F, Vagnarelli F, Gargano G et al. Early intracardiac thrombosis in preterm infants and thrombolysis with recombinant tissue type plasminogen activator. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;85(1):66. doi: 10.1136/fn.85.1.F66. doi:10.1136/fn.85.1.f66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beneri CA, Nicolau DP, Seiden HS, Rubin LG. Successful treatment of a neonate with persistent vancomycin-resistant enterococcal bacteremia with a daptomycin-containing regimen. Infect Drug Resist. 2008;1:9–11. doi: 10.2147/idr.s3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seybold U, Halvosa JS, White N et al. Emergence of and risk factors for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus of community origin in intensive care nurseries. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):1039–1046. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(3):285–292. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cubist Pharmaceuticals US Cubicin package insert. Lexington, MA: 2014. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2003/21-572_Cubicin.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gawronski KM. Successful use of daptomycin in a preterm neonate with persistent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis bacteremia. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2015;20(1):61–65. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-20.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Smith PB, Benjamin DK et al. Daptomycin use in infants: report of two cases with peak and trough drug concentrations. J Perinatol. 2008;28(3):233–234. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antachopoulos C, Iosifidis E, Sarafidis K et al. Serum levels of daptomycin in pediatric patients. Infection. 2012;40(4):367–371. doi: 10.1007/s15010-011-0240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayram N, Düzgöl M, Kara A et al. Linezolid-related adverse effects in clinical practice in children. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2017;115(5):470–475. doi: 10.5546/aap.2017.eng.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan K, Jones BL, Jackson L. Auditory nerve neuropathy in a neonate after linezolid treatment. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(2):169. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31818fd8f5. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e31818fd8f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daptomycin. Lexicomp Online, Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs Online. Hudson, OH: Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information Inc; https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/pdh_f/128599?searchUrl=%2Flco%2Faction%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Ddaptomycin%26t%3Dname%26va%3Ddaptomycin Updated 2018. Accessed January 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley JS, Nelson JD, Barnett E Nelson's Pediatric Antimicrobial Therapy. 23rd ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarafidis K, Iosifidis E, Gikas E et al. Daptomycin use in a neonate: serum level monitoring and outcome. Am J Perinatol. 2010;27(5):421–424. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1243370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enoxaparin. Lexicomp Online, Pediatric and Neonatal Lexi-Drugs Online. Hudson, OH: Wolters Kluwer Clinical Drug Information Inc; 2018. https://online-lexi-com.winthrop.idm.oclc.org/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/pdh_f/129858 Accessed January 28, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maraqa NF, Aigbivbalu L, Masnita-Iusan C et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and infection among infants at a level III neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39(1):35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Y, Chou Y, Su L et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization and its association with infection among infants hospitalized in neonatal intensive care units. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):469–474. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carey AJ, Della-Latta P, Huard R et al. Changes in the molecular epidemiological characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a neonatal intensive care unit. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(6):613–619. doi: 10.1086/652526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zervou FN, Zacharioudakis IM, Ziakas PD, Mylonakis E. MRSA colonization and risk of infection in the neonatal and pediatric ICU: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):e1015–e1023. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson AP, Sharland M, Goodall CM et al. Enhanced surveillance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteraemia in children in the UK and Ireland. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(10):781–785. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.162537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Namtu KC, Crain JC, Messina AF et al. Clinical experience with daptomycin in pediatrics. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37(1):105–108. doi: 10.1002/phar.1872. doi:10.1002/phar.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lexicomp Online, Pediatric and Neonatal. Daptomycin Pediatric Drug information. UpToDate; 2018. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/daptomycin-pediatric-drug-information?search=daptomycin%20children&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1~64&usage_type=default&display_rank=1 Accessed January 15, 2018.

- 26.Syrogiannopoulos GA, Michoula AN, Petinaki E, Grivea IN. Daptomycin use in children: experience with various types of infection and age groups. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(10):962–966. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hussain A, Kairamkonda V, Jenkins DR. Successful treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in a neonate using daptomycin. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60(Pt 3):381–383. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.027235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garazzino S, Castagnola E, Di Gangi M et al. Daptomycin for children in clinical practice experience. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2016;35(6):639–641. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Watt KM, Hornik CP et al. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of single-dose daptomycin in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(9):935–937. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31825d2fa2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klaassen ILM, van Ommen CH, Middeldorp S. Manifestations and clinical impact of pediatric inherited thrombophilia. Blood. 2015;125(7):1073–1077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-536060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monagle P, Chan AKC, Goldenberg NA et al. Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e801S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2308. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fan JL, Roberts LE, Scheurer ME et al. Association of outcomes and anti-Xa levels in the treatment of pediatric venous thromboembolism. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(11) doi: 10.1002/pbc.26629. doi:10.1002/pbc.26629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michaels LA, Gurian M, Hegyi T, Drachtman RA. Low molecular weight heparin in the treatment of venous and arterial thromboses in the premature infant. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):703–707. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]