Abstract

Flexion instability after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is caused by an increased flexion gap as compared to extension gap. Patients present with recurrent effusions, subjective instability (especially going downstairs), quadriceps weakness, and diffuse peri-retinacular pain. Manual testing for laxity in flexion is commonly done to confirm a diagnosis, although testing positions and laxity grades are inconsistent. Non-operative treatment includes quadriceps strengthening and bracing. The mainstays to operative management of femoral instability involve increasing the posterior condylar offset, decreasing tibial slope, raising the joint line in combination with a thicker polyethylene insert, and ensuring appropriate rotation of components. Patient outcomes after revision TKA for flexion instability show the least amount of improvement when compared to revisions for other TKA failure etiologies. Future work is needed to unify reproducible diagnostic criteria. Advancements in biomechanical analysis with motion detection, isokinetic quadriceps strength testing, and computational modeling are needed to advance the collective understanding of this underappreciated failure mechanism.

Keywords: Flexion Instability, Total knee arthroplasty, Biomechanics, Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty, Stress radiographs, Laxity

Background

Instability is one of the four most common failure mechanisms in contemporary total knee arthroplasty (TKA), accounting for 11–26% of failures 1–3. Flexion instability can present with other forms of instability (coronal or global instability), but as an isolated condition, it can be difficult to accurately diagnose and manage 4,5. We aim to review the available literature on this topic and highlight efforts needed to unify diagnostic criteria, including physical exam findings, radiographic parameters, and biomechanical testing.

Definition & Causes

Fundamentally, flexion instability is the result of a flexion space that is larger or more lax than the extension gap 6. When the knee is bent to 90°, the resultant loss of articular congruity from the lax flexion space diminishes the compressive load on the knee and increases the force needed to achieve joint stability 7. This imbalance places undue stress onto the surrounding supporting structures of the knee (quadriceps, extensor mechanism, hamstrings, and collateral ligaments), leading to symptoms of instability during activities of weight bearing when the knee is flexed. Flexion instability is caused by an inability to balance the flexion and extension space at the time of index arthroplasty or from gradual laxity of the posterior capsule or posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) in cruciate retaining (CR) designed components 8,9 (Table 1). Flexion instability may also occur with posterior stabilized (PS) knee designs10. Gap symmetry and soft tissue balancing remain indispensible to prevent excessive anterior translation without cam-post impingement or dislocation. Technical factors that can lead to flexion instability include too little distal femoral resection in a preexisting flexion contracture (Fig. 1), overly aggressive posterior condylar resection with undersized femoral components (Fig. 2), excessive posterior slope on the tibia (Fig. 3), or over-release of the PCL in the CR knee 6,11.

Table 1 -.

Sagittal Balancing Errors and Those Leading to Flexion Instability (red)

| Flexion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tight | Balanced | Loose | ||

| Extension | Tight | Not enough tibial resection | Not enough distal femur resection | Femoral component undersized |

| Tight posterior capsule | Not enough distal femur resection | |||

| Balanced | Not enough posterior femur resection | Well balanced knee | Too much posterior femoral condylar resection | |

| PCL too tight | Increased tibial slope resection | |||

| Loose | Oversized femoral component | Too much distal femur resection | Too much tibial resection | |

Figure 1.

In patients with pre-existing flexion contracture, it is possible to create a situation of flexion instability when the surgeon does not resect enough distal femur (a). The shaded area signifies the bone that should have been cut to properly balance the gaps. This scenario with under resection of the distal femur translates to a knee remaining tight in extension (b) necessitating the surgeon use a thin polyethylene insert, thereby increasing the flexion space (c) thereby creating laxity in flexion.

Figure 2.

An overly aggressive posterior condylar resection can lead to flexion instability. These bone cuts often lead to undersizing of the femoral component, thereby not recreating the appropriate posterior femoral offset, as indicated by the dashed line.

Figure 3.

By cutting too much posterior slope into the tibia, the gap posteriorly increases disproportionately to the extension gap. This allows the knee to roll posterior on the tibia in flexion, thereby translating the tibia anterior, leading to flexion instability.

Mid-flexion instability

While flexion instability is described as laxity at 90 degrees of flexion, mid-flexion instability is believed to be a different entity that is linked to rotational instability between 30° and 90° of flexion 12. The cause of such rotational instability is debated, but is thought to have a relation to the isometry of the collateral ligaments throughout the arc of motion. Mid-flexion instability has yet to be reproducibly described in clinical practice, but is believed to present with subtle instability and pain when going from fully extended to early flexion with full muscle activation, such as ascending stairs 13. Causes of mid-flexion instability are not agreed upon, with postulations ranging from altered ligament tension during motion from raising the joint line 14,15, anterior positioning of the femoral prosthesis 16, or multi-radius femoral component designs 17,18. Currently, it is difficult to discern differences between true mid-flexion and flexion instability.

Diagnosis

Clinical Presentation & Symptoms

Patients who present with flexion instability usually have a constellation of complaints. They characteristically report a sense of distrust with their knee and that it wants to “shift” or “slide”, classically when rising from a seated position or navigating stairs 8. Often, the knee never felt well since the index arthroplasty. Some patients who received a CR-TKA may have excellent early flexion, but soon develop feelings of instability as the anterior restraints (quadriceps and extensor mechanism) fatigue and chronic anterior knee pain develops 9. This feeling of instability when the knee is loaded in flexion activities is what the vast majority of patients notice. However, flexion contractures can sometimes develop in cases of flexion instability. The purported mechanism for this counterintuitive phenomenon is that the quadriceps becomes overworked trying to provide sagittal support, leading to a weakened extensor mechanism. When combined with a tight posterior capsule (from a preoperative flexion contracture), the knee can assume a flexed resting position in this unique setting 19. A high percentage of patients also complain of diffuse peri-retinacular tenderness and recurrent low-grade effusions 20.

Physical Exam

Although flexion instability is often thought of a diagnosis of exclusion, it remains a clinical diagnosis. While many authors have reported excessive anteroposterior (AP) translation in 90° of flexion as a mainstay of diagnosing flexion instability, no consensus exists quantifying the amount of motion that is pathologic. Abdel et al described tibial translation as “mild” for motion of <5mm, “moderate” if between 5mm-1cm, and “marked” if >1cm of AP motion was present to diagnosis flexion instability 21. Tibial translation is measured in a similar manner to an anterior drawer test for ACL rupture in native knees, where an abrupt maneuver when the leg is fully relaxed provides the qualitative sense of instability. There have been no correlation studies to confirm the reproducibility of these measurements, however. Furthermore, it can be difficult to fully assess flexion instability when patients present with chronic pain and guarding. Stability testing should also be in mid-flexion and extension should be performed as well.

Others have described testing translation under anesthesia (Video 1), but specific steps and thresholds defining instability are ill-defined 20,22. Pagnano et al described a posterior sag sign in which the tibia translates posteriorly when the knee is flexed to 90° and the heel is supported on the table to relax the quadriceps 8,10. Again, no cutoffs for pathologic translation have been quantified for this test. Vince et al has also described an exam maneuver to diagnose instability in which the patient is seated at the end of the exam table with the knee bent over the edge and the quadriceps is relaxed 6. If flexion instability is present, the larger flexion space will cause the tibia to descend and bring the polyethylene out of contact with the posterior condyles. When the patient is asked to actively extend, the physician will note the tibia “pull up” to articulate with the femur upon initiation of quadriceps contraction, and only after this contact is reestablished will the tibia extend.

Additional exam findings include recurrent aseptic effusions. Hernandez et al showed that more than 60% of patients with a diagnosis of flexion instability had a serosanguinous aspiration with less than 500 nucleated cells 23. Because of increased stresses placed on secondary musculotendinous stabilizers of the knee in cases of true flexion instability, a physician can also elicit pain by palpating the pes anserine and hamstring tendons. It is not uncommon to discover bursal swelling and irritation overlying the pes tendon insertion along the medial tibia 8.

Physicians should also consider the possibility of concomitant mutli-ligament imbalance, since flexion instability does not always present in isolation. Yoshihara et al described a subset of patients with flexion instability who also had greater than 4° of medial laxity and 7° of lateral laxity in flexion as more likely to be symptomatic than those without mediolateral laxity in flexion. Those with multiplanar instability in flexion need to have femoral rotation scrutinized and should receive a varus-valgus constraining prosthesis to avoid recurring symptomatic laxity 24. Lastly, the patient’s gait should be observed, with attention placed on coronal and AP motion and overall stance to see how a patient may be compensating for a contracture of laxity in a given plane 25.

Radiographs & Work-up

The diagnosis of flexion instability is made only after a thorough work-up for other common failure mechanisms. Serum inflammatory markers should be evaluated and an aspiration should be performed as directed by the Clinical Practice Guidelines set forth by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) 26. Prior operative report and implant stickers should be requested from the index arthroplasty when a revision operation is being considered.

As with any evaluation, a complete weight-bearing radiograph series, including AP, lateral and sunrise views, should be obtained to scrutinize fixation, alignment, placement, and sizing of components 27. Full-length AP and lateral hip-knee-ankle radiographs should be evaluated for overall limb alignment potential joint line distalization. When a high suspicion for flexion instability exists, one should closely inspect the lateral radiograph to calculate the slope of the tibial tray and the posterior femoral condylar offset 21. The size of the polyethylene insert and other radiographic clues, such as patella baja, may suggest a postoperative alteration in joint kinematics. The surgeon should also request preoperative radiographs as a comparison to obtain a better sense of femoral component positioning in relation to the epicondylar axis 21. A lateral of the contralateral knee, if not replaced, may also assist. Advanced scintigraphic or three-dimensional imaging is not necessary to confirm flexion instability, but could be useful in cases of concomitant loosening or combined instability patterns where component malrotation is involved 6. And while stress radiographs in 90° of flexion could prove useful, no literature exists to guide its current use or how to interpret such findings when planning a surgical correction.

Current Management

Nonoperative: Therapy

There is a paucity of literature regarding the role of non-operative treatment for flexion instability. Some authors have mentioned a limited role for nonoperative measures, as the problem is viewed strictly as mechanical 28. However, we are not aware of any specific recommendations or protocols in terms of bracing, therapy or pain control. Most patients with flexion instability can likely benefit from quadriceps strengthening, as quadriceps weakness is related to the overworked extensor mechanism needed to initiate motion (Figure 4). A stronger quadriceps may help improve instability in flexion, and isometric quadriceps testing can provide a quantitative strength measurement to guide rehabilitation. A knee brace may also help with subjective feelings of instability. Further research is necessary to determine the utility of quadriceps-strengthening programs on subsequent laxity measures and their role in improving patient reported outcomes and possible avoidance of revision TKA.

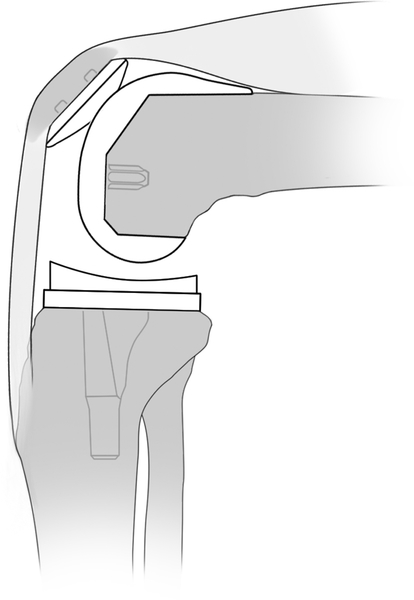

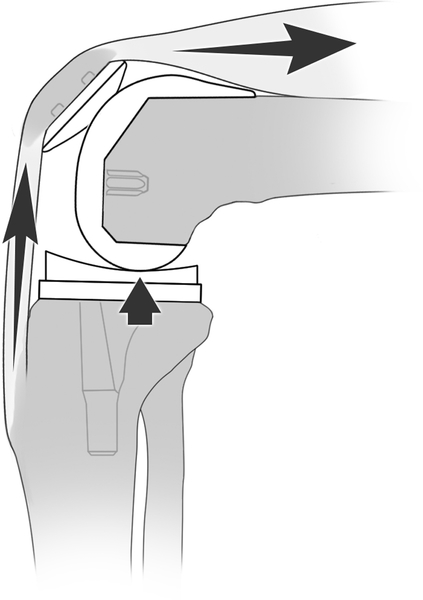

Figure 4.

When a patient with flexion instability rest with their knee at a 90 degree flexed position without their foot contacting the floor, the femoral component does not contact the polyethylene (a). In order to initiate knee extension, the quadriceps and extensor mechanism must first contract to pull the tibia up to contact the femur (b) before any extension can occur. The quadriceps must generate additional increased force to subsequently extend the knee once femoral-polyethylene contact is established (c).

Operative: Revision TKA

For patients who have failed a trial of conservative management, revision surgery should be considered to address the underlying cause of flexion-extension gap mismatch. In cases of prior well-functioning CR knees that have gone on to late instability due to PCL incompetence, the knee should be revised to a more constrained component. Depending on manufacturer specifications, it may be possible to keep a well-fixed tibial tray and only revise the femoral component in this setting 8. It is imperative, though, that the surgeon evaluate the flexion and extension spaces intraoperative, as it is possible that excessive tibial slope may necessitate removal of a tibial tray to appropriately balance the spaces and prevent post-cam impingement in extension.

Abdel et al provided a generalized intraoperative sequence to guide equalization of the flexion and extension gaps 21. The suggested order of correction is to first normalize the tibial slope followed by adjusting component axis of rotation, correcting coronal imbalances, increasing femoral AP dimension, and raising the joint line. The surgeon should recheck the gaps at each step up the ladder and stop when gap symmetry and equalization is achieved. Vince proposed a similar sequence for reestablishing equal flexion and extension spaces: 1) create a stable tibial platform, as this affects both extension and flexion gaps; 2) flexion gap balancing with larger and appropriately rotated femoral component; 3) extension gap matching by adjusting proximal-distal placement of the femoral prosthesis 6. We have included a flow diagram of our recommended intraoperative steps to address flexion instability (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Flow diagram highlighting operative steps during revision knee surgery to address flexion instability.

Upsize Polyetheylene

Treating flexion instability by only increasing the bearing size must be approached with caution. This practice is inherently limited, as it equally adds to the extension and flexion space. Schwab et al described this practice in their early experience for treating flexion instability 10. In two of their 10 patients, they managed the instability by using a thicker posterior-stabilized polyethylene in combination with extensive posterior capsule release. While both patients had reported pain relief, one had a flexion contracture that never improved. The overall outcomes of isolated polyethylene exchange in revision knee arthroplasty are modest at best, with reports of a 50% failure rate within three years 29. Due to the risk of not achieving full extension and adequately balancing the gaps, the use of isolated bearing upsizing is discouraged for isolated flexion instability.

Larger Femoral Component

A mainstay of revision surgery for flexion instability should be to increase the posterior condylar offset by using a femoral component with a larger AP dimension 6,21. If the contralateral knee has not been replaced, the lateral radiograph can be used as a comparison when planning femoral revision to anticipate femoral component size 11. Femoral rotation should be checked with the knee in flexion using the tibial cut surface and native transepicondylar as references. Trial blocks or a tensioning device should be used to then set the rotation of the femur along an axis that parallels the tibial surface 21. Upsizing the femur may lead to a gap between the posterior condyle and the implant, which should be managed with metal augmentation (Figure 6). Trialing with the larger components is important to determine that any adjustments in femoral positioning and rotation allow for appropriate patellar tracking. The surgeon should aim for <5mm of anterior tibial translation when the patella is reduced and the knee is at 90° of flexion 21.

Figure 6.

Lateral radiographs demonstrating flexion instability as a result of over-resection of the posterior femoral condyle (a) that was surgically corrected by increasing the posterior femoral offset by 4mm using a revision femoral component and posterior augment (b).

Joint Line Elevation

If the flexion and extension spaces cannot be adequately balanced by the above measures, the next step is to increase the extension space by resecting more distal femur 10,21. Abdel et reported needing to raise the joint line >5mm in 56% of cases in their series, but that the vast majority required both increased posterior femoral offset plus distal femoral resection (52/60 revisions) 21. The need to resect more distal femur is often encountered when the PCL becomes incompetent and the flexion space grows unequally. Chronic attrition of the PCL may place strain on the MCL, resulting in a combined instability pattern. Revision in this situation requires a more constrained prosthesis 20.

Constraint

When a proper sequence for balancing is followed, a surgeon may be able to rely on a cruciate-substituting bearing for a first-time revision for flexion instability 21. The posterior stabilized design provides a cam-post mechanism that limits tibial translation at varying degrees flexion as the post engages. This post also confers an element of axial stability to prevent frank dislocation, deemed “jump distance” due to its dimensions 30. However, often flexion instability is accompanied by medial lateral instability. In situations when coronal laxity is encountered after removal of existing implants, it is often necessary to turn to varus-valgus constraint to confer additional stability 5. Vince believed that many cases of flexion instability had a component of collateral insufficiency that was masked in full extension due to the tight posterior capsule 9. A condylar linked hinge prosthesis should be considered in cases where significant femoral bone loss affects the epicondyles and compromises functionality of the collaterals or when the flexion space is so large that equalization to the extension space is impossible.

Outcomes

While patients tend to make gains in their pain and functional scales after revision for flexion instability, the aggregate improvement is not as predictable compared to revisions for other etiologies 31. Abdel et al cited significant improvements in mean Knee Society Score (KSS) and KSS functional scale scores in their series of 60 revisions for flexion instability at mean 3.6 years follow-up 21. Kannan et al reported that 75% (27/36) of patients had improvements in function with an average 27.3 point gain in overall KSS (34.5 to 61.8) and a 20.8 point improvement in KSS function (39.5 to 60.8) at a mean of 32 months and a minimum of 1-year 20. All patients in this cohort had a femoral revision, 8 of whom received a PS bearing while 29 others required a varus-valgus constrained insert due to persistent laxity in flexion. They were unable to show an association with preoperative factors such as age, gender, BMI and original bearing type (CR vs. PS) and improvement in outcome scores. Additionally, there was no association in terms of level of subjective improvement compared to the amount of radiological correction of the posterior condylar offset or tibial slope.

When comparing revisions for flexion instability (n=35) to those done for infection or aseptic loosening, Grayson et al found that the overall drop in median KSS expectation scores was significantly worse in flexion instability patients (6 points vs. 3 points each, respectively; p=0.02) 31. These nuanced findings suggest that flexion instability patients experienced more disappointment with their results one-year after revision surgery. This assumption was confirmed by an analysis of expectations, which showed that 40–60% of flexion instability patients were somewhat or a lot worse in terms of meeting their expectations for pain relief, ability to perform ADLs, and participation in recreational activities. In their comparative study regarding outcomes of revisions for flexion instability versus those done for aseptic loosening and infection, Rajgopal et al noted that patients with flexion instability often had significantly higher pre-revision KSS and WOMAC scores, which may explain the smaller increments for improvement even though they reached similar scores at 2-year follow-up 22. Lastly, Luttjeboer et al reported that patients who received a condylar hinge compared to a varus-valgus constrained insert at revision had significantly worse KSS scores in all domains but similar patient satisfaction scores at 2-year follow-up 32. The nineteen subjects who received a PS insert, however, had an 80% complication rate with recurrent instability being the main culprit.

Future Directions

Physical Exam Grading System

The current gold standard for diagnosis is the tibial translation test where the examiner subjectively grades instability as either <5mm, 5–10mm and >10mm 21 with a consistent position of the knee, namely 90° of flexion with the quadriceps relaxed and the foot free (open-chain). Different practitioners have not tested these measurements in a blinded and repeated manner on the same patients to determine inter and intra-observer bias. Likewise, measurements of mid-flexion instability and medial-lateral instability are currently not quantitative. These also may be affected by pain and muscle inhibition. The amount of inherent stability of a knee system that leads to good clinical results may also vary by prosthesis design. AP translation of 5–10mm is normal for some patients, as suggested by the improved subjective outcomes at 2-years in those who had CR TKAs 33. The ability to obtain reproducible measurements will remain paramount to appropriately diagnosing and treating patients with painful knee replacements.

Stress Radiography & Laxity Testing

While ACL and PCL laxity can be routinely measured after ligament reconstruction, this has not been adopted after knee replacement. Stress radiography may allow us to unite flexion instability calculations. After TKA, Seon et al have described a protocol in which a Telos™ stress device (Austin & Associated, Inc., Millersville, MD) is used to apply a consistent anterior force of 150 N to the tibia with the knee in 90° of flexion 34. They obtained lateral X-rays of the knee before and during force application, with measurements of displacement determined as the horizontal distance between a vertical line from the posterior aspect of the tibial tray and a vertical line from the posterior aspect of the femoral condyle. When reviewing 46 cruciate-retaining TKAs of a single manufacture (Aesculap e-motion®, Tuttligen, Germany) placed with navigation, the same authors reported an average sagittal translation of 7.1mm (SD 4.1mm). Interestingly, they found that improved postoperative range of motion was correlated with AP translation >5mm, similar to that of earlier studies 35. Their study was unable to determine an upper limit of AP motion before impairment in joint function and stability.

Future efforts should focus on comparing patients with symptoms of flexion instability to sagittal displacement on stress measurements. Besides Telos™, other arthrometers have been studied in the biomechanics literature. The KT-1000™ is a device used to measure the sum of the anterior and posterior tibial translation with the knee in 20–30° of flexion with 97 N force constantly applied 33. The GNRB® arthrometer is a device that gradually increases load from 0 to 250N over the tibial tubercle with the knee in 20° of flexion and digitally measures the posterior displacement from the tubercle to the anterior femur 36. The Rolimeter™ measures anterior tibial translation when the physician applies a maximum Lachman force to the tibia with the knee in 20° of flexion. A theoretic benefit of such devices is that is does not expose the patient to undue radiation to compute displacement, as radiography is not required. However, previous protocols for the use of these devices often called for relaxation of the limb to eliminate patient guarding, which detracts from its ease-of-use and generalizability for patients with painful knee replacements. To date, the KT-1000™, GNRB® and Rolimeter™ devices have not been tested specifically for flexion instability knee arthroplasty and have predominantly been used to measure knee laxity in patients with cruciate ligament injuries.

Motion-tracking sensors and wearable accelerometers have also gained popularity and could provide details regarding functional instability during certain movements and help establish thresholds for patient perceptions of laxity 37.

Biomechanical Testing & Computational Modeling

Knee stability is comprised from three general mechanisms that have significantly interplay: articular congruity, ligamentous constraint and muscle activation 38. Because of varying component designs and differing baseline laxity grades and muscle strength amongst individuals, knee stability after TKA may actually be a patient-specific occurrence. Recent research has shown that quadriceps and hamstrings can co-contract to generate added compressive forces across the knee joint in the first-year after TKA that may improve joint stability 39. To that end, future research needs to quantify differences in quadriceps and hamstring co-contraction and determine differences in knees with and without flexion instability. Combining efforts with computational modeling to create simulations that incorporate ligamentous structure and balancing, implant design, component positioning, and coordinated muscle contractions and strength measures will allow for an improved understanding of the relative contributions each of these domains has in the normal and physiologically unstable TKA 7. These efforts can further be advanced with kinematic gait and motion analysis studies to elucidate differences in loading patterns and step length between those with and without flexion instability after knee replacement 40.

Summary

The experience of flexion instability after total knee arthroplasty is likely a patient-specific phenomenon that depends on the interaction of a multitude of implant, surgical and host factors. Patients often present with recurrent effusions, subjective instability quadriceps weakness, and diffuse knee pain. The mainstay of non-operative treatment involves isometric quadriceps strengthening. Revision surgery is frequently needed to increase femoral component offset to tighten the flexion space to achieve balanced flexion and extension gaps. This process usually entails a full revision TKA, as increasing the polyethylene bearing size alone leads to persistent gap imbalance. Patient outcomes after revision TKA for flexion instability show the least amount of improvement when compared to revisions for other TKA failure etiologies.

In order to better care for patients with flexion instability, unified diagnostic criteria must be established that considers the weighted contributions of the amount of sagittal laxity, radiographic positioning and alignment of components, and the input of the surrounding muscles as secondary stabilizers. This will allow future studies to determine if any subset of flexion unstable patients can improve with non-operative measures and lead to comparisons of surgical strategies to enhance patient outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Video 1. Physical examination of flexion instability with patient fully relaxed, demonstrating Grade 3 laxity (>10mm translation).

Acknowledgments

There were not external grants or funding sources used to support this research

References

- 1.Sharkey PF, Lichstein PM, Shen C, Tokarski AT, Parvizi J. Why Are Total Knee Arthroplasties Failing Today—Has Anything Changed After 10 Years? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(9):1774–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalury DF, Pomeroy DL, Gorab RS, Adams MJ. Why are Total Knee Arthroplasties Being Revised? J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8):120–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le DH, Goodman SB, Maloney WJ, Huddleston JI. Current modes of failure in TKA: infection, instability, and stiffness predominate. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(7):2197–2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cottino U, Sculco PK, Sierra RJ, Abdel MP. Instability After Total Knee Arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47(2):311–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Instability Following Total Knee Arthroplasty. HSS J. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vince KG. Diagnosis and management of patients with instability of the knee. Instr Course Lect. 2012;61:515–524. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22301258. Accessed February 16, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rullkoetter PJ, Fitzpatrick CK, Clary CW. How can we use computational modeling to improve total knee arthroplasty? Modeling stability and mobility in the implanted knee. In: Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagnano MW, Hanssen AD, Lewallen DG, Stuart MJ. Flexion instability after primary posterior cruciate retaining total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;(356):39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vince KG, Abdeen A, Sugimori T. The unstable total knee arthroplasty: causes and cures. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(4 Suppl 1):44–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwab JH, Haidukewych GJ, Hanssen AD, Jacofsky DJ, Pagnano MW. Flexion instability without dislocation after posterior stabilized total knees. In: Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research.; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang MJ, Lim H, Lee NR, Moon Y-W. Diagnosis, Causes and Treatments of Instability Following Total Knee Arthroplasty. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2014;26(2):61–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramappa M Midflexion instability in primary total knee replacement: a review. SICOT-J. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vince K Mid-flexion instability after total knee arthroplasty: Wooly Thinking or a Real Concern? Bone Jt J. 2016;98(1):84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evangelista PJ, Laster S, Lenz N, Sheth NP, Schwarzkopf R. A computer model of mid-flexion instability in a balanced total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;0(0). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.König C, Matziolis G, Sharenkov A, et al. Collateral ligament length change patterns after joint line elevation may not explain midflexion instability following TKA. Med Eng Phys. 2011;33(10):1303–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin JW, Whiteside LA. The influence of joint line position on knee stability after condylar knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(259):146–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Simpson KJ, Ferrara MS, Chamnongkich S, Kinsey T, Mahoney OM. Biomechanical differences exhibited during sit-to-stand between total knee arthroplasty designs of varying radii. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(8):1193–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jo A-R, Song E-K, Lee K-B, Seo H-Y, Kim S-K, Seon J-K. A comparison of stability and clinical outcomes in single-radius versus multi-radius femoral design for total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(12):2402–2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saleh KJ, Lee LW, Gandhi R, et al. Quadriceps strength in relation to total knee arthroplasty outcomes. Instr Course Lect. 2010;59:119–130. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20415375. Accessed February 21, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kannan A, O’Connell RS, Kalore N, Curtin BM, Hull JR, Jiranek WA. Revision TKA for flexion instability improves patient reported outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdel MP, Pulido L, Severson EP, Hanssen AD. Stepwise surgical correction of instability in flexion after total knee replacement. Bone Jt J. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajgopal A, Panjwani TR, Rao A, Dahiya V. Are the Outcomes of Revision Knee Arthroplasty for Flexion Instability the Same as for Other Major Failure Mechanisms? J Arthroplasty. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernandez NM, Taunton MJ, Perry KI, Mara KC, Hanssen AD, Abdel MP. The analysis of synovial fluid in total knee arthroplasties with flexion instability. Bone Jt J. 2017;9911(11):1477–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshihara Y, Arai Y, Nakagawa S, et al. Assessing coronal laxity in extension and flexion at a minimum of 10 years after primary total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petrie JR, Haidukewych GJ. Instability in total knee arthroplasty : assessment and solutions. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B(1 Suppl A):116–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Della Valle C Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Joint Infections (PJI) - Clinical Practice Summary. JAAOS. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yercan HS, Ait Si Selmi T, Sugun TS, Neyret P. Tibiofemoral instability in primary total knee replacement: a review, Part 1: Basic principles and classification. Knee. 2005;12(4):257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clarke HD, Scuderi GR. Flexion instability in primary total knee replacement. J Knee Surg. 2003;16(2):123–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babis GC, Trousdale RT, Morrey BF. The effectiveness of isolated tibial insert exchange in revision total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(1):64–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnout N, Vanlommel L, Vanlommel J, et al. Post-cam mechanics and tibiofemoral kinematics: a dynamic in vitro analysis of eight posterior-stabilized total knee designs. Knee Surgery, Sport Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grayson CW, Warth LC, Ziemba-Davis MM, Michael Meneghini R. Functional Improvement and Expectations Are Diminished in Total Knee Arthroplasty Patients Revised for Flexion Instability Compared to Aseptic Loosening and Infection. J Arthroplasty. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luttjeboer JS, Bénard MR, Defoort KC, van Hellemondt GG, Wymenga AB. Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty for Instability—Outcome for Different Types of Instability and Implants. J Arthroplasty. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seah RB, Pang HN, Lo NN, et al. Evaluation of the relationship between anteroposterior translation of a posterior cruciate ligament-retaining total knee replacement and functional outcome. J Bone Jt Surg Br. 2012;94:1362–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seon JK, Song EK, Yoon TR, Bae BH, Park SJ, Cho SG. In vivo stability of total knee arthroplasty using a navigation system. Int Orthop. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warren PJ, Olanlokun TK, Cobb AG, Walker PS, Iverson BF. Laxity and function in knee replacements. A comparative study of three prosthetic designs. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(305):200–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robert H, Nouveau S, Gageot S, Gagnière B. A new knee arthrometer, the GNRB®: Experience in ACL complete and partial tears. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan H, Walker PS, Zuckerman JD, et al. The Potential of Accelerometers in the Evaluation of Stability of Total Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright TM. Joint stability in total knee arthroplasty: What is the target for a stable knee? In: Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.; 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lundberg HJ, Rojas IL, Foucher KC, Wimmer MA. Comparison of Antagonist Muscle Activity During Walking Between Total Knee Replacement and Control Subjects Using Unnormalized Electromyography. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(6):1331–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alnahdi AH, Zeni JA, Snyder-Mackler L. Gait after unilateral total knee arthroplasty: frontal plane analysis. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(5):647–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video 1. Physical examination of flexion instability with patient fully relaxed, demonstrating Grade 3 laxity (>10mm translation).