Abstract

Inflammatory pseudotumors imitate neoplasms on imaging but actually represent focal inflammation. We report a case of follicular pancreatitis, which is a recently recognized distinct form of mass-forming focal chronic pancreatitis pathologically characterized by lymphoid infiltration with abundant reactive germinal centers. In our patient, follicular pancreatitis manifested as a pancreatic tail mass that was resected due to imaging findings, which were suggestive of pancreatic malignancy. We performed a literature review of this rare condition and present a summary of reported imaging findings. The most distinguishing feature from pancreatic adenocarcinoma is the enhancement pattern, as follicular pancreatitis enhances more than the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma on delayed post-contrast images which is unusual for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. If this benign diagnosis is suggested on imaging, unnecessary surgery and its potential complications may be avoided.

Keywords: follicular pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis, mass-forming pancreatitis

1. Introduction

Focal inflammation within the pancreas can appear as a mass on imaging and mimic a neoplasm. Various distinct forms of focal pancreatitis have been described including alcoholic, autoimmune, groove, and xanthogranulomatous pancreatitis [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Recently, follicular pancreatitis has been recognized as a distinct form of focal chronic pancreatitis in the pathology literature [7, 8, 9, 6]. Follicular pancreatitis is a very rare form of chronic pancreatitis and is usually mistaken for a pancreatic neoplasm. Only 13 cases have been reported in the literature to date [7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. However, 6 earlier case reports with diagnoses such as lymphoid hyperplasia or pseudolymphoma of the pancreas were also likely follicular pancreatitis cases [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. Except for a single case, all reported cases have been managed surgically with the diagnosis made postoperatively even when biopsy of the pancreatic masses indicated nonneoplastic disease because results were interpreted as discordant with the imaging findings [9]. If follicular pancreatitis is diagnosed prior to surgery, morbidity and mortality associated with unnecessary surgery can be avoided [18, 19, 20].

We present a case of follicular pancreatitis and describe and illustrate the imaging findings. For the first time, we report the presence of diffusion restriction in follicular pancreatitis on MRI. In addition, we performed a literature review of this newly described entity focusing on its imaging appearance.

2. Case report

A 75-year-old male with a past medical history significant for coronary artery disease, initially presented to the emergency department complaining of 2 days of dyspnea and epigastric pain with mild nausea. A pulmonary-embolism-protocol chest CT revealed consolidation in the lateral right lung apex consistent with pneumonia. Due to the patient’s abdominal pain, a single-phase contrast-enhanced abdominal CT was performed which showed a 2.8 cm pancreatic tail mass, a finding not present on a prior CT obtained 13 months earlier (Figure 1). No peripancreatic fat stranding was present. No enlarged lymph nodes were present in the abdomen. Initial laboratory results showed mild leukocytosis but were otherwise unremarkable. In particular, serum lipase was within normal limits.

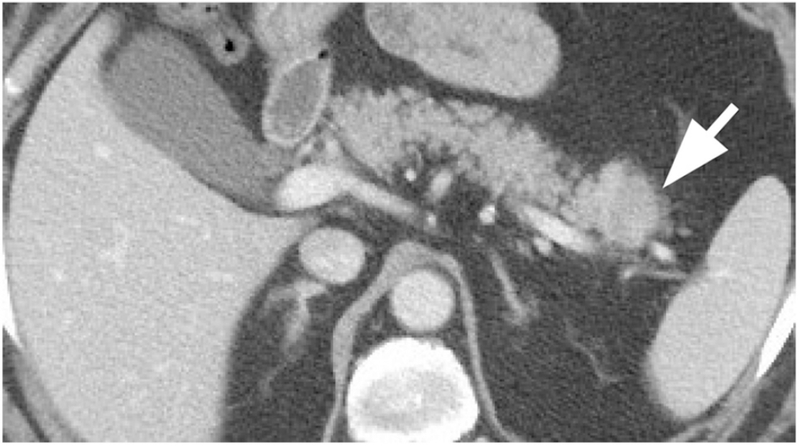

Figure 1:

Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT in the portal venous phase demonstrated a 2.8 cm hypodense pancreatic tail mass (arrow).

The patient was admitted to the hospital and treated with antibiotics for pneumonia. Prior to discharge, MRI of the pancreas was performed which re-demonstrated the 2.8 cm pancreatic tail mass (Figure 2). Relative to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma, the mass was hypointense on non-contrast T1-weighted images and isointense on T2-weighted images. No peripancreatic inflammatory changes were present, in particular on the fat-suppressed T2-weighted images. The main pancreatic duct and common bile duct were normal. The apparent diffusion coefficient of the pancreatic mass was 1474 μm2/s, while the apparent diffusion coefficient of the normal pancreatic parenchyma was 1664 μm2/s, compatible with diffusion restriction. Comparison of T1-weighted in-phase and out-of-phase images did not reveal any appreciable signal decrease within the mass or between the mass and the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma. On the dynamic post-contrast imaging (gadobutrol), the pancreatic mass was initially hypointense in the late hepatic arterial phase but became isointense relative to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma in the portal venous phase. On more delayed post-contrast phases after two or more minutes after contrast administration, the pancreatic mass became hyperintense relative to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma. The pancreatic mass reached peak enhancement at about two minutes after contrast administration. Enhancement of the pancreatic mass decreased slightly within the obtained delayed phases extending to 3.5 min after contrast administration, but throughout all of the obtained delayed phases, the mass remained hyperintense relative to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma. The radiology report described the mass as concerning for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

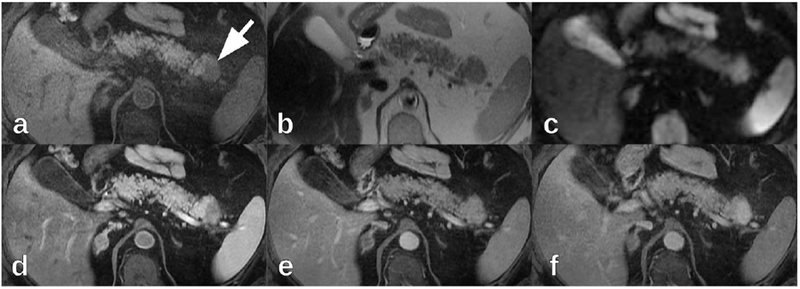

Figure 2:

On 1.5 T MRI, the pancreatic tail mass (arrow) was (a) hypointense on axial non-contrast fat-suppressed T1-weighted images, (b) isointense on axial T2-weighted images, and (c) hyperintense on axial diffusion-weighted imaging (b=600 mm2/s). On axial post-contrast fat-suppressed T1-weighted imaging (gadobutrol), the pancreatic tail mass was (d) hypointense in the late hepatic arterial phase, (e) isointense in the portal venous phase, and (f) hyperintense in delayed phases.

Subsequently, endoscopic ultrasound demonstrated a well-defined, hypoechoic, solid-appearing pancreatic tail mass (Figure 3). The remainder of the pancreas including the main pancreatic duct and peripancreatic vessels was unremarkable. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transgastric fine needle aspiration of the pancreatic tail mass did not reveal any evidence of epithelial malignancy but did demonstrate mostly lymphoid cells, which could not be fully characterized due to scant cellularity. Clinically, the pathology results were considered non-diagnostic given the imaging findings.

Figure 3:

Endoscopic ultrasound demonstrated a well-defined, hypoechoic, solid-appearing pancreatic tail mass.

As a part of malignancy staging, 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed one month after initial presentation which demonstrated that the pancreatic tail mass had elevated FDG uptake (SUVmax 4.8) (Figure 4). Lateral apical right lung consolidation was re-demonstrated and had elevated FDG uptake (SUVmax 4.2), possibly representing neoplasm or inflammation.

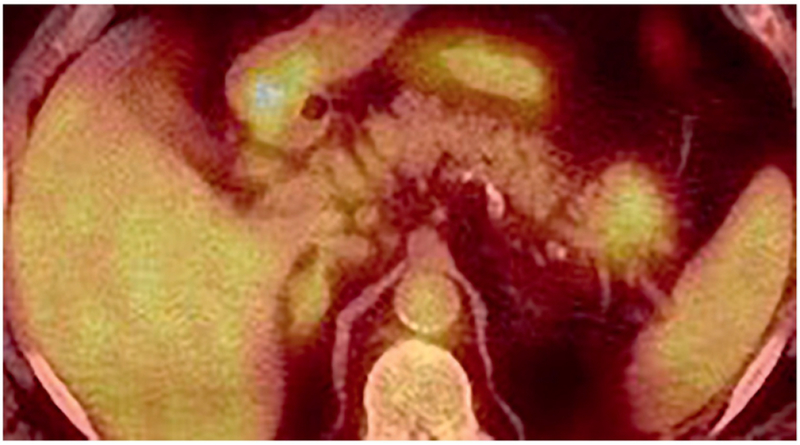

Figure 4:

On 18F-FDG PET/CT, the pancreatic tail mass had elevated FDG uptake (SUVmax 4.8).

With a preoperative diagnosis of presumed pancreatic adenocarcinoma, the patient underwent laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy. In the distal pancreas, grossly there was a tan/pink, firm, lobulated, well-defined mass measuring 2.2 cm. The mass grossly abutted the splenic vein, but there was no definite vascular involvement. The spleen and omentum were unremarkable without any masses or lesions. Histopathology of the pancreatic tail mass demonstrated atrophic pancreatic acini, lymphoid infiltrates with many reactive germinal centers throughout the pancreatic lobules and surrounding adipose tissue, and moderate to severe stromal fibrosis (Figure 5). Periductal lymphoid infiltrates without germinal centers were also present. Bcl-2 immunonegativity confirmed the reactive nature of the germinal centers. Scattered plasma cells were polytypic by kappa/lambda immunostains. These findings were inconsistent with lymphoma. Obliterative phlebitis and partially obliterated arteries were observed, confirmed by elastin stain. Less than five IgG4-positive plasma cells were seen per high power field, and no storiform fibrosis or granulocytic epithelial lesion was identified, which was incompatible with autoimmune pancreatitis. The final pathologic diagnosis was chronic pancreatitis with many reactive germinal centers, which was most compatible with follicular pancreatitis.

Figure 5:

Hematoxylin and eosin stained slides of the pancreatic tail mass demonstrated scattered lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers and atrophic changes of the pancreatic acini and ducts at (a) 40x magnification and (b) 100x magnification.

Unfortunately, surgery was complicated by development of a chronic pancreatic fistula with peripancreatic fluid collections requiring multiple drainage procedures. The patient’s postoperative course was also complicated by pulmonary embolism. Persistence of the consolidation in the lateral right lung apex on a follow up chest CT was suspicious for malignancy that was confirmed by CT-guided biopsy demonstrating lung adenocarcinoma. Complications of the distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy delayed treatment of the patient’s primary lung adenocarcinoma.

3. Discussion

Recently, follicular pancreatitis has been recognized as a distinct form of focal chronic pancreatitis. We present a summary of the clinical, pathologic, and imaging characteristics of all cases of follicular pancreatitis, pancreatic lymphoid hyperplasia, and pancreatic pseudolymphoma published in English and indexed in PubMed or referenced by an identified publication.

All of the reported cases have occurred in patients 40 years old or older with most occurring in patients older than 50 years (Table 1). While 12 cases have occurred in male patients, 8 female patients have been affected. Some patients presented with abdominal pain, jaundice, or liver enzyme elevation. However, nearly half of reported cases were incidental.

Table 1:

Each cell contains the fraction of cases with the clinical characteristic in the leftmost column corresponding to the publication in the top row. The numerator is the number of cases having the characteristic. The denominator is the number of cases in which the characteristic is reported to be present or absent. Each follicular pancreatitis publication is represented by a column in this table. The rightmost column contains the fraction of all reported cases with each characteristic in the leftmost column. The column marked by * represents our case.

| [12] | [13] | [14] | [15] | [16] | [7] | [17] | [8] | [9] | [10] | [11] | * | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 2/6 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 1/1 | 5/20 |

| Diaphoresis | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 1/7 | |||||||

| Jaundice | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 2/2 | 1/1 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 4/11 | ||||

| Liver enzyme elevation | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 2/2 | 1/1 | 2/6 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 7/18 | ||

| Malaise | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 2/8 | ||||||

| Weight loss | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/2 | 0/4 | 0/3 | 2/12 | ||||||

| Incidental | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 4/6 | 0/1 | 3/3 | 0/1 | 9/20 |

| 40–49 years old | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/6 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 1/20 |

| 50–59 years old | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 2/6 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 4/20 |

| 60–69 years old | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/2 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 3/6 | 0/1 | 2/3 | 0/1 | 9/20 |

| ≥70 years old | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/2 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/6 | 1/1 | 1/3 | 1/1 | 6/20 |

| Female | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/2 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 2/6 | 0/1 | 1/3 | 0/1 | 8/20 |

| Male | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 2/2 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 4/6 | 1/1 | 2/3 | 1/1 | 12/20 |

Unfortunately, most of the reported cases of follicular pancreatitis have only been identified retrospectively after resection, sometimes with surgical complications as occurred in our case. Recurrence of follicular pancreatitis after resection has never been reported with follow up extending up to five years. Two cases reported spontaneous resolution after incomplete resection [16, 10]. However, one of those cases reported the subsequent development of hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma involving the liver at 46 and 102 months respectively after diagnosing follicular pancreatitis [10]. Interestingly, one reported case of follicular pancreatitis was treated with steroids resulting in a 50% decrease in size [9] suggesting that follicular pancreatitis like autoimmune pancreatitis may be steroid responsive.

Follicular pancreatitis is characterized by lymphoid follicles with reactive germinal centers. Scattered plasma cells are polyclonal, and IgG4-positive plasma cells are not increased, while IgG4-positive plasma cells are increased in type 1 autoimmune pancreatitis. No storiform fibrosis or granulocytic epithelial lesion is present, which are characteristic pathologic features of type 1 and type 2 autoimmune pancreatitis respectively. Periductal germinal centers are common in follicular pancreatitis but apparently not always present as described in 2 of 13 reported cases including our case [15]. Obliterative phlebitis is an infrequent pathologic finding in follicular pancreatitis with only 4 of 14 cases reporting some inflammatory obliteration of veins (Table 2). Some authors propose that follicular pancreatitis may represent a third type of autoimmune pancreatitis [11].

Table 2:

Each cell contains the fraction of cases with the histopathology finding in the leftmost column corresponding to the publication in the top row. The numerator is the number of cases having the finding. The denominator is the number of cases in which the finding is reported to be present or absent. Each follicular pancreatitis publication is represented by a column in this table. The rightmost column contains the fraction of all reported cases with each finding in the leftmost column. The column marked by * represents our case.

In most reported cases, imaging has demonstrated a single pancreatic mass anywhere from the uncinate process to the pancreatic tail (Table 3). Multiple pancreatic masses have been reported in 4 of 20 cases. In two cases, imaging did not reveal any pancreatic masses, although the imaging technique used is unclear [9]. Occasionally, the presence of common bile duct or main pancreatic duct dilation have been observed [12, 13, 9]. Main pancreatic duct stenosis has also been reported [7]. The most consistently reported imaging finding is a hypoechoic pancreatic lesion on ultrasound, which has been reported in 9 of 9 cases (Table 4) indicating relatively homogeneous acoustic impedance of follicular pancreatitis compared to normal pancreatic parenchyma. Doppler ultrasound typically demonstrates hypovascularity within the mass. In the one case, which reported non-contrast CT findings, the pancreatic mass was isodense relative to the rest of the pancreas (Table 5). In the five cases, which reported non-contrast MRI findings, the pancreatic mass was hypointense in T1-weighted images and either isointense or mildly hyperintense in T2-weighted images (Table 6). Hypointensity on T1-weighted images is expected given atrophy of the pancreatic acini, which normally contain proteinaceous fluid and account for much of the T1-weighted signal in normal pancreatic parenchyma [22, 23, 24]. Isointensity to mild hyperintensity in T2-weighted images suggests minimal edema in follicular pancreatitis.

Table 3:

Each cell contains the fraction of cases with the imaging finding in the leftmost column corresponding to the publication in the top row. The numerator is the number of cases having the finding. The denominator is the number of cases in which the finding is reported to be present or absent. Each follicular pancreatitis publication is represented by a column in this table. The rightmost column contains the fraction of all reported cases with each finding in the leftmost column. The column marked by * represents our case.

| [12] | [13] | [14] | [15] | [16] | [7] | [17] | [8] | [9] | [10] | [11] | * | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No pancreatic mass | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 2/6 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 2/20 |

| Single pancreatic mass | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 2/2 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 4/6 | 1/1 | 2/3 | 1/1 | 14/20 |

| Multiple pancreatic masses | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/2 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/6 | 0/1 | 1/3 | 0/1 | 4/20 |

| Uncinate process mass | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/6 | 0/1 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 2/20 |

| Pancreatic head mass | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 2/2 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1/6 | 1/1 | 0/3 | 0/1 | 7/20 |

| Pancreatic body mass | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/2 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/6 | 0/1 | 1/3 | 0/1 | 5/20 |

| Pancreatic tail mass | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/2 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 2/6 | 0/1 | 3/3 | 1/1 | 9/20 |

| Bile duct dilation | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/4 | ||||||||

| Pancreatic duct dilation | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 2/6 | 0/1 | 4/11 | ||||||

| Pancreatic duct stenosis | 2/2 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 2/4 | |||||||||

Table 4:

Each cell contains the fraction of cases with the ultrasound finding in the leftmost column corresponding to the publication in the top row. The numerator is the number of cases having the finding. The denominator is the number of cases in which the finding is reported to be present or absent. Each follicular pancreatitis publication with ultrasound findings is represented by a column in this table. The rightmost column contains the fraction of all reported cases with each finding in the leftmost column. The column marked by * represents our case. Hypoechoic and hypovascular are in comparison to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma.

Table 5:

Each cell contains the fraction of cases with the CT finding in the leftmost column corresponding to the publication in the top row. The numerator is the number of cases having the finding. The denominator is the number of cases in which the finding is reported to be present or absent. Each follicular pancreatitis publication with CT findings is represented by a column in this table. The rightmost column contains the fraction of all reported cases with each finding in the leftmost column. The column marked by * represents our case. Hypodense, isodense, and hyperdense are in comparison to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma. Contrast enhancement phases are defined as in LI-RADS [21].

Table 6:

Each cell contains the fraction of cases with the MRI finding in the leftmost column corresponding to the publication in the top row. The numerator is the number of cases having the finding. The denominator is the number of cases in which the finding is reported to be present or absent. Each follicular pancreatitis publication with MRI findings is represented by a column in this table. The rightmost column contains the fraction of all reported cases with each finding in the leftmost column. The column marked by * represents our case. Hypointense, isointense, and hyperintense are in comparison to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma. Contrast enhancement phases are defined as in LI-RADS [21].

| [14] | [16] | [17] | [8] | * | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-contrast T1-hypointense | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 5/5 |

| T2-isointense | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 3/5 |

| T2-hyperintense | 1/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 2/5 |

| Hepatic arterial T1-hypointense | 1/1 | 1/1 | 2/2 | |||

| Portal venous T1-isointense | 0/1 | 0/1 | 1/1 | 1/3 | ||

| Portal venous T1-hyperintense | 1/1 | 1/1 | 0/1 | 2/3 | ||

| Delayed T1-hyperintense | 1/1 | 1/1 | 1/1 | 3/3 | ||

| DWI hyperintense | 1/1 | 1/1 | 2/2 | |||

| ADC hypointense | 1/1 | 1/1 | ||||

In follicular pancreatitis, contrast enhancement in multiphase CT and MRI is similar (Tables 5 and 6). The pancreatic masses in follicular pancreatitis are typically hypodense or hypointense in the hepatic arterial phase but gradually increase in enhancement transitioning to isodensity or isointensity near the portal venous phase and become hyperdense or hyperintense on delayed phases [14, 16, 17, 8]. Although pancreatic adenocarcinoma is also hypodense or hypointense in the hepatic arterial phase and demonstrates delayed gradual enhancement, hypodensity or hypointensity compared to the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma usually persists even into delayed phases when peak enhancement occurs in pancreatic adenocarcinoma [25]. This pattern of dynamic enhancement, which is intermediate between normal pancreatic parenchyma and pancreatic adenocarcinoma with slower and less contrast enhancement than normal pancreatic parenchyma but faster and greater contrast enhancement than pancreatic adenocarcinoma, has been observed in other forms of chronic pancreatitis [26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 25]. Delay of peak enhancement relative to normal pancreatic parenchyma is likely due to decreased microvascular density as is sometimes reported in the histological findings of follicular pancreatitis. High delayed enhancement is compatible with increased interstitium reflected by numerous lymphoid follicles and interfollicular fibrosis [32, 33]. The contrast enhancement of follicular pancreatitis is distinct from hypervascular masses such as typical pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and intrapancreatic splenules [34] because follicular pancreatitis exhibits less contrast enhancement than normal pancreatic parenchyma during the hepatic arterial phase.

For the first time, we report the presence of diffusion restriction in follicular pancreatitis. While hyperintensity on diffusion-weighted imaging has been previously reported, the presence of mild hyperintensity on T2-weighted images and the omission of reported apparent diffusion coefficient values makes distinguishing diffusion restriction from T2 shine-through impossible [8]. There have been conflicting studies comparing diffusion restriction in focal chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic adenocarcinoma [35]. Some of the discrepancies in study results are probably due to failure to account for heterogeneity in the forms of chronic pancreatitis. When accounting for specific forms of chronic pancreatitis, autoimmune pancreatitis has been found to have apparent diffusion coefficient values lower than normal pancreas, while alcoholic chronic pancreatitis has apparent diffusion coefficient values similar to normal pancreas [36]. Moreover, autoimmune pancreatitis typically has lower apparent diffusion coefficient values than pancreatic adenocarcinoma, which usually demonstrates lower apparent diffusion coefficient values than normal pancreatic parenchyma [37, 25]. Diffusion restriction in follicular pancreatitis is expected since similar to autoimmune pancreatitis there is lymphoid infiltration, which is presumably the origin of diffusion restriction in autoimmune pancreatitis. Unfortunately, due to lack of calibration in diffusion-weighted imaging, distinguishing follicular pancreatitis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma based on comparison of apparent diffusion coefficient values to published values is likely to be difficult in practice.

In general, we expect imaging findings of follicular pancreatitis to be most similar to mass-forming focal autoimmune pancreatitis. This is not surprising because both follicular pancreatitis and autoimmune pancreatitis are composed of lymphocytes and fibrosis. Imaging is presumably insensitive to the differences in microscopic arrangement of lymphocytes and fibrosis. However, distinguishing follicular pancreatitis from autoimmune pancreatitis may be possible based on macroscopic distribution of disease. Even among the subset of focal autoimmune pancreatitis cases that are suspicious for pancreatic adenocarcinoma, non-focally elevated pancreatic FDG uptake is slightly more common than focally elevated uptake [38, 39, 40], whereas focally elevated FDG uptake has been observed in 4 of 4 cases in follicular pancreatitis (Table 7). 18F-FDG PET/CT may also detect extrapancreatic manifestations of IgG4-related disease, which would be more suggestive of autoimmune pancreatitis than follicular pancreatitis. Of note, nonspecific chronic pancreatitis generally does not demonstrate focally elevated FDG uptake [41, 42, 43, 44]. 18F-FDG PET/CT could help identify metastatic disease compatible with malignancy, although there are two case reports of hepatic lesions being associated with follicular pancreatitis [15, 10]. Discriminating follicular pancreatitis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma based on SUVmax will probably be unreliable since distinguishing nonspecific focal chronic pancreatitis from pancreatic adenocarcinoma based on SUVmax is difficult [45].

Table 7:

Each cell contains the fraction of cases with the pancreatic FDG uptake pattern on PET described in the leftmost column corresponding to the publication in the top row. The numerator is the number of cases having the uptake pattern. The denominator is the number of cases in which the uptake pattern is reported to be present or absent. Each follicular pancreatitis publication with PET findings is represented by a column in this table. The rightmost column contains the fraction of all reported cases with each uptake pattern in the leftmost column. The column marked by * represents our case.

The development of this profile of follicular pancreatitis imaging findings has three limitations: small sample size, variability in imaging technique of published cases, and reporting bias of findings. These limitations are partially mitigated by the strong correspondence with the expected imaging findings given pancreatic diseases with similar pathophysiologic features relevant to the contrast mechanism of the imaging technique.

Until increased awareness of follicular pancreatitis leads to more recognized cases and more data, we propose the following management algorithm. If a solid pancreatic mass demonstrates greater contrast enhancement than the surrounding pancreatic parenchyma on delayed phases, then the mass should be biopsied. If biopsy reveals lymphoid infiltration without evidence of malignancy and all imaging findings are consistent with the imaging profile of follicular pancreatitis including diffusion restriction, then follicular pancreatitis is a reasonable diagnosis and nonoperative management should be considered to avoid morbidity and mortality associated with surgery. When biopsy suggests follicular pancreatitis but imaging findings do not match the imaging profile of follicular pancreatitis, unrepresentative tissue sampling and another diagnosis should be suspected. Because follicular pancreatitis is very rare, an atypical presentation of a more common disease may be more probable when imaging and pathology are not completely consistent with a diagnosis of follicular pancreatitis.

Highlights.

Follicular pancreatitis is a rare form of mass-forming focal chronic pancreatitis.

On imaging, follicular pancreatitis imitates pancreatic malignancy.

Follicular pancreatitis hyperenhances on delayed images which is unusual for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

On MRI, follicular pancreatitis exhibits diffusion restriction.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number T32EB005970].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest

None. The funding source was not involved in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing, or the decision to submit for publication.

References

- [1].Klöppel G, Chronic pancreatitis, pseudotumors and other tumor-like lesions, Modern Pathology 20 (2007) S113–S131. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Klöppel G, Adsay NV, Chronic pancreatitis and the differential diagnosis versus pancreatic cancer, Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine 133 (3) (2009) 382–387. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165-133.3.382. URL https://www.archivesofpathology.org/doi/abs/10.1043/1543-2165-133.3.382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Coakley FV, Hanley-Knutson K, Mongan J, Barajas R, Bucknor M, Qayyum A, Pancreatic imaging mimics: Part 1, imaging mimics of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, American Journal of Roentgenology 199 (2) (2012) 301–308. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.7907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Raman SP, Salaria SN, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, Groove pancreatitis: Spectrum of imaging findings and radiology-pathology correlation, American Journal of Roentgenology 201 (1) (2013) W29–W39. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kwon JH, Kim JH, Kim SY, Byun JH, Kim HJ, Hong S-M, Lee M-G, Lee SS, Imaging and clinical features of xanthogranulomatous pancreatitis: an analysis of 10 cases at a single institution, Abdominal Radiology 43 (12) (2018) 3349–3356. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Zen Y, Deshpande V, Tumefactive inflammatory diseases of the pancreas, The American Journal of Pathology 189 (1) (2019) 82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.05.022. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002944018302025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zen Y, Ishikawa A, Ogiso S, Heaton N, Portmann B, Follicular cholangitis and pancreatitis – clinicopathological features and differential diagnosis of an under-recognized entity, Histopathology 60 (2) (2012) 261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04078.x. URL https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.04078.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mizuuchi Y, Aishima S, Hattori M, Ushijima Y, Aso A, Takahata S, Ohtsuka T, Ueda J, Tanaka M, Oda Y, Follicular pancreatitis, report of a case clinically mimicking pancreatic cancer and literature review, Pathology - Research and Practice 210 (2) (2014) 118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2013.09.005. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0344033813002318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gupta RK, Xie BH, Patton KT, Lisovsky M, Burks E, Behrman SW, Klimstra D, Deshpande V, Follicular pancreatitis: a distinct form of chronic pancreatitis—an additional mimic of pancreatic neoplasms, Human Pathology 48 (2016) 154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.09.017. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0046817715003603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kaneko R, Mitomi H, Nakazaki N, Yano Y, Ogawa M, Sato Y, Primary hepatic lymphoma complicated by a hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor and tumor-forming pancreatitis, Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases 26 (3) (2017) 299–304. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.263.eko. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ryota H, Ishida M, Satoi S, Yanagimoto H, Yamamoto T, Kosaka H, Hirooka S, Yamaki S, Kotsuka M, Matsui Y, Ikeura T, Uchida K, Takaoka M, Okazaki K, Tsuta K, Clinicopathological and immunological features of follicular pancreatitis – a distinct disease entity characterised by Th17 activation, Histopathology 74 (5) (2019) 709–717. doi: 10.1111/his.13802. URL https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/his.13802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nakashiro H, Tokunaga O, Watanabe T, Ishibashi K, Kuwaki T, Localized lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma) of the pancreas presenting with obstructive jaundice, Human Pathology 22 (7) (1991) 724–726. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(91)90297-3. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0046817791902973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hatzitheoklitos E, Buchler M, Friess H, DiSebastiano P, Poch B, Beger H, Mohr W, Pseudolymphoma of the pancreas mimicking cancer, Pancreas 9 (5) (1994) 668–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kim JW, Shin SS, Heo SH, Jeong YY, Kang HK, Choi YD, Imaging findings of localized lymphoid hyperplasia of the pancreas: a case report, Korean Journal of Radiology 12 (4) (2011) 510–514. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2011.12.4.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Amer A, Mafeld S, Saeed D, Al-Jundi W, Haugk B, Charnley R, White S, Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the liver and pancreas. a report of two cases and a comprehensive review of the literature, Clinics and Research in Hepatology and Gastroenterology 36 (4) (2012) e71–e80. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.12.004. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2210740111004037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nakata B, Amano R, Matsuoka J, Sugimori S, Ohsawa M, Wakasa K, Egashira Y, Kimura K, Yamada N, Hirakawa K, Spontaneously complete regression of pseudolymphoma of the remnant pancreas after pancreaticoduodenectomy, Pancreatology 12 (3) (2012) 215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2012.02.011. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1424390312000440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Christophides T, Frampton AE, Cohen P, Gall TMH, Jiao LR, Habib NA, Pai M, Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the pancreas: A clinical conundrum, Journal of the Pancreas 14 (2) (2013) 207–211. doi: 10.6092/1590-8577/1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Pitt HA, Talamini MA, Hruban RH, Ord SE, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Zahurak ML, Grochow LB, Abrams RA, Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: Pathology, complications, and outcomes, Annals of Surgery 226 (3) (1997) 248–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sledzianowski J, Duffas J, Muscari F, Suc B, Fourtanier F, Risk factors for mortality and intra-abdominal morbidity after distal pancreatectomy, Surgery 137 (2) (2005) 180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.06.063. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0039606004005562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Goh BKP, Tan Y-M, Chung Y-FA, Cheow P-C, Ong H-S, Chan W-H, Chow PKH, Soo K-C, Wong W-K, Ooi LLPJ, Critical appraisal of 232 consecutive distal pancreatectomies with emphasis on risk factors, outcome, and management of the postoperative pancreatic fistula: A 21-year experience at a single institution, Archives of Surgery 143 (10) (2008) 956–965. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.10.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kambadakone AR, Fung A, Gupta RT, Hope TA, Fowler KJ, Lyshchik A, Ganesan K, Yaghmai V, Guimaraes AR, Sahani DV, Miller FH, LI-RADS technical requirements for CT, MRI, and contrast-enhanced ultrasound, Abdominal Radiology 43 (1) (2018) 56–74. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1325-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Semelka RC, Ascher SM, MR imaging of the pancreas, Radiology 188 (3) (1993) 593–602. doi: 10.1148/radiology.188.3.8351317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Manikkavasakar S, AlObaidy M, Busireddy KK, Ramalho M, Nilmini V, Alagiyawanna M, Semelka RC, Magnetic resonance imaging of pancreatitis: An update, World Journal of Gastroenterology 20 (40) (2014) 14760–14777. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Ansari NA, Ramalho M, Semelka RC, Buonocore V, Gigli S, Maccioni F, Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the detection and characterization of solid pancreatic nodules: An update, World Journal of Radiology 7 (11) (2015) 361–374. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v7.i11.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Choi S-Y, Kim SH, Kang TW, Song KD, Park HJ, Choi Y-H, Differentiating mass-forming autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma on the basis of contrast-enhanced MRI and DWI findings, American Journal of Roentgenology 206 (2) (2016) 291–300. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kim JK, Altun E, Elias J Jr, Pamuklar E, Rivero H, Semelka RC, Focal pancreatic mass: Distinction of pancreatic cancer from chronic pancreatitis using gadolinium-enhanced 3d-gradient-echo MRI, Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 26 (2) (2007) 313–322. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21010. URL https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jmri.21010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Suzuki K, Itoh S, Nagasaka T, Ogawa H, Ota T, Naganawa S, CT findings in autoimmune pancreatitis: assessment using multiphase contrast-enhanced multisection CT, Clinical Radiology 65 (9) (2010) 735–743. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.06.002. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0009926010002229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yamada Y, Mori H, Matsumoto S, Kiyosue H, Hori Y, Hongo N, Pancreatic adenocarcinoma versus chronic pancreatitis: differentiation with triple-phase helical CT, Abdominal Imaging 35 (2) (2010) 163–171. doi: 10.1007/s00261-009-9579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lu N, Feng X-Y, Hao S-J, Liang Z-H, Jin C, Qiang J-W, Guo Q-Y, 64-slice CT perfusion imaging of pancreatic adenocarcinoma and mass-forming chronic pancreatitis, Academic Radiology 18 (1) (2011) 81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2010.07.012. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1076633210004253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kim JH, Lee JM, Park JH, Kim SC, Joo I, Han JK, Choi BI, Solid pancreatic lesions: Characterization by using timing bolus dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging assessment—a preliminary study, Radiology 266 (1) (2013) 185–196. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Sun G-F, Zuo C-J, Shao C-W, Wang J-H, Zhang J, Focal autoimmune pancreatitis: Radiological characteristics help to distinguish from pancreatic cancer, World Journal of Gastroenterology 19 (23) (2013) 3634–3641. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i23.3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Koh TS, Shi W, Thng CH, Kwek JW, Bisdas S, Khoo JBK, Interpretation and applicability of empirical tissue enhancement metrics in dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI based on a multiple pathway model, Physics in Medicine and Biology 57 (15) (2012) N279–N294. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/15/n279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cuenod C, Balvay D, Perfusion and vascular permeability: Basic concepts and measurement in DCE-CT and DCE-MRI, Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging 94 (12) (2013) 1187–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2013.10.010. URL http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2211568413003306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Raman SP, Hruban RH, Cameron JL, Wolfgang CL, Fishman EK, Pancreatic imaging mimics: Part 2, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and their mimics, American Journal of Roentgenology 199 (2) (2012) 309–318. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.8627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Barral M, Taouli B, Guiu B, Koh D-M, Luciani A, Manfredi R, Vilgrain V, Hoeffel C, Kanematsu M, Soyer P, Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of the pancreas: Current status and recommendations, Radiology 274 (1) (2015) 45–63. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14130778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Taniguchi T, Kobayashi H, Nishikawa K, Iida E, Michigami Y, Morimoto E, Yamashita R, Miyagi K, Okamoto M, Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in autoimmune pancreatitis, Japanese Journal of Radiology 27 (3) (2009) 138–142. doi: 10.1007/s11604-008-0311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kamisawa T, Takuma K, Anjiki H, Egawa N, Hata T, Kurata M, Honda G, Tsuruta K, Suzuki M, Kamata N, Sasaki T, Differentiation of autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer by diffusion-weighted MRI, American Journal of Gastroenterology 105 (8) (2010) 1870–1875. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Ozaki Y, Oguchi K, Hamano H, Arakura N, Muraki T, Kiyosawa K, Momose M, Kadoya M, Miyata K, Aizawa T, Kawa S, Differentiation of autoimmune pancreatitis from suspected pancreatic cancer by fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, Journal of Gastroenterology 43 (2) (2008) 144–151. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2132-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lee TY, Kim M-H, Park DH, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim JS, Lee KT, Utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT for differentiation of autoimmune pancreatitis with atypical pancreatic imaging findings from pancreatic cancer, American Journal of Roentgenology 193 (2) (2009) 343–348. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zhang J, Jia G, Zuo C, Jia N, Wang H, 18F-FDG PET/CT helps differentiate autoimmune pancreatitis from pancreatic cancer, BMC Cancer 17 (1) (2017) 695. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3665-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Friess H, Langhans J, Ebert M, Beger HG, Stollfuss J, Reske SN, Büchler MW, Diagnosis of pancreatic cancer by 2[18F]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography, Gut 36 (5) (1995) 771–777. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.5.771. URL https://gut.bmj.com/content/36/5/771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Stollfuss JC, Glatting G, Friess H, Kocher F, Berger HG, Reske SN, 2-(fluorine-18)-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET in detection of pancreatic cancer: value of quantitative image interpretation, Radiology 195 (2) (1995) 339–344. doi: 10.1148/radiology.195.2.7724750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].van Kouwen MC, Jansen JB, van Goor H, de Castro S, Oyen WJ, Drenth JP, FDG-PET is able to detect pancreatic carcinoma in chronic pancreatitis, European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 32 (4) (2005) 399–404. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kauhanen SP, Komar G, Seppanen MP, Dean KI, Minn HR, Kajander SA, Rinta-Kiikka I, Alanen K, Borra RJ, Puolakkainen PA, Nuutila P, Ovaska JT, A prospective diagnostic accuracy study of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography, multidetector row computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging in primary diagnosis and staging of pancreatic cancer, Annals of Surgery 250 (6) (2009) 957–963. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b2fafa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kato K, Nihashi T, Ikeda M, Abe S, Iwano S, Itoh S, Shimamoto K, Naganawa S, Limited efficacy of 18F-FDG PET/CT for differentiation between metastasis-free pancreatic cancer and mass-forming pancreatitis, Clinical Nuclear Medicine 38 (6) (2013) 417–421. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3182817d9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]