Abstract

Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) maintain the balance between cell proliferation and cell death by inhibiting caspase activities and mediating immune responses. In the present study, a homolog of IAP (designated as EsIAP1) was identified from Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. EsIAP1 consisted of 451 amino acids containing two baculoviral IAP repeat (BIR) domains with the conserved Cx2 Cx6 Wx3 Dx5 Hx6 C motifs. EsIAP1 mRNA was expressed in various tissues and its expression level in hemocytes increased significantly (p < 0.01) at 12–48 h after lipopolysaccharide stimulation. In the hemocytes, EsIAP1 protein was mainly distributed in the cytoplasm. The hydrolytic activity of recombinant EsCaspase-3/7-1 against the substrate Ac-DEVD-pNA decreased after incubation with rEsIAP1. Moreover, rEsIAP1 could directly combine with rEsCaspase-3/7-1 in vitro. After EsIAP1 was interfered by dsRNA, the mRNA expression and the hydrolytic activity of EsCaspase-3/7-1 increased significantly, which was 2.26-fold (p < 0.05) and 1.71-fold (p < 0.05) compared to that in the dsGFP group, respectively. These results collectively demonstrated that EsIAP1 might play an important role in apoptosis pathway by regulating the activity of EsCaspase-3/7-1 in E. sinensis.

Subject terms: Innate immunity, Transcription

Introduction

Apoptosis is a type of cell death which plays an important role in regulating growth, development, and immune responses1,2. Apoptosis is tightly controlled by multiple regulators, and the interaction between positive and negative regulators determines whether this program is activated or inhibited3. A family of cysteine-aspartic specific proteases known as caspases are considered as the executors of apoptosis, which cleave their substrates after the aspartate residue leading to protein degradation and apoptosis4. The modulation of apoptosis can be achieved by the dynamic expression of BCL-2 protein family members as well as the inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs)5,6.

IAP was firstly recognized in baculoviruses which could inhibit apoptosis in infected cells in 19937. Subsequently, numerous IAP homologues have been identified in vertebrates, which is primarily devided into five groups including X-linked IAP (XIAP), c-IAP1, c-IAP2, NAIP, and Survivin8. All the IAPs contain one to three baculovirus IAP repeats (BIR) domains, which is consisted of approximately 70 amino acid residues6. The IAP family members differ in the number of BIR domains, and some of them also contain a RING finger domain. XIAP, c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 comprise three BIRs in the N-terminus and a RING finger in the C-terminus, while NAIP contains three BIRs without RING finger domain, and Survivin and BRUCE include only one BIR9. Accumulating evidences have favored that some vertebrate IAPs, such as XIAP, c-IAP1 and c-IAP2, could directly bind to the activated caspase-3 and -7, and inhibit their activities10,11. The BIR domains have been suggested to be responsible for the inhibition of caspases12,13. For instance, the BIR motifs of c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 from Homo sapiens were evidenced for their ability to inhibit active recombinant caspases in vitro10. The BIR2 of XIAP from H. sapiens, but not the BIR1 or the BIR3, was able to interact with caspase-3 and -7 with an apparent inhibition14. It was reported that the RING finger domain in IAPs could coordinate two zinc atoms15. In H. sapiens, the RING finger domain of XIAP could act as an E3 ubiquitin ligase16. Moreover, it could also recruit E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes and transfer ubiquitin to its target proteins bound to IAPs17–19.

Recently, IAP homologues have also been discovered in various species of invertebrates. The invertebrate IAP homologues also contain one to three BIR domains, and some of them possess a RING finger domain. Some invertebrate IAPs were found to share the similar function with their homologues in vertebrates, which could play vital roles in the regulation of apoptosis and immune response against invading pathogens. For example, DIAP1 and DIAP2 were identified in fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster with two and three BIR domains, respectively20,21. DIAP2 was able to regulate the expression of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) in response to gram-negative bacterial infection through modulating the immune deficiency (IMD) pathway in D. melanogaster22,23. LvIAP1 with three BIR domains identified from shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei was reported to play vital roles in the regulation of shrimp hemocyte apoptosis response against white spot syndrome virus stimulation24. Two IAPs (named as CgIAP1 and CgIAP2) containing two BIR domains were characterized in pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas, and they were found to to be involved in regulating the apoptosis pathway and immune defense against bacterial infections25,26. It has been demonstrated that some IAPs could inhibit the activation of caspases in invertebrates. DIAP1 could interact with caspase DRONC and interfere its activation in D. melanogaster21. The BIR2 domain of CgIAP2 could interact with the initiator caspase CgCaspase-2 to participate in apoptosis inhibition25. The diverse caspase family members have also been discovered in various species of crustacean. For example, three caspases (EsCaspase-3, -7 and -8) were characterized in E. sinensis to play crucial roles in Cadmium-induced apoptosis27, and two caspases (EsCaspase-3/7-1 and EsCaspase-3-like) were involved in innate immune response under pathogen induced apoptosis28,29. In shrimp L. vannamei, there were four caspases (LvCaspase-2, -3, -4 and -5) identified to play role in the host defense against white spot syndrome virus30. Compared with vertebrate IAPs and caspases, the knowledge about the interaction modes of the large family of invertebrate IAPs and caspases as well as their involvements in apoptosis is still quite meagre.

E. sinensis is one of the important economic species, and the industry of E. sinensis aquaculture has been increasing rapidly in China31. With the development of aquaculture, various diseases caused by bacteria, viruses or other pathogenic organisms have frequently occurred in cultured E. sinensis and caused catastrophic losses32. Therefore, the better understanding of immune response mechanism is helpful for controlling the diseases and reducing economic losses. In crabs, hemocytes are found to play crucial roles in defending against pathogen invasion and they can be induced to apoptosis after pathogen stimulation33. IAPs as inhibitors of apoptosis proteins play critical roles in inhibiting the cell apoptosis. In the present study, a novel IAP (designated as EsIAP1) was identified from Chinese mitten crab E. sinensis with the objectives (1) to investigate its mRNA distribution in tissues and its mRNA expression profile in response to immune stimulations, (2) to determine its subcellular localization in crab hemocytes, (3) to validate the interaction of rEsIAP1 and rEsCaspase-3/7-1 in vitro, as well as the potential regulation between EsIAP1 and EsCaspase-3/7-1 in vivo, hopefully to provide more information to understand the apoptosis regulation mechanism in crustaceans.

Results

The sequence characteristics and phylogeny of EsIAP1

A novel sequence of EsIAP1 (GenBank accession numbers MF351747) was identified from E. sinensis genome database. The open reading frame of EsIAP1 was of 1,356 bp, encoding a predicted polypeptide of 451 amino acids with calculated molecular weight of approximately 50 kDa. SMART analysis demonstrated that EsIAP1 contained two BIR domains (BIR1 and BIR2). The conserved cysteine and histidine residues and the spacing between them in the reported BIR2 domains (Cx2 Cx6 Wx3 Dx5 Hx6 C) were also identified in the BIR2 domain of EsIAP1 (Fig. 1a). The deduced amino acid sequences of BIR1 and BIR2 domains of EsIAP1 shared high sequence similarities with the corresponding domains of other IAPs, such as those from L. vannamei IAP1 (40.5% and 50.7%), Mus musculus XIAP (43.1% and 45.9%), H. sapiens c-IAP2 (45.8% and 53.4%), H. sapiens XIAP (41.7% and 47.3%), M. musculus c-IAP2 (44.4% and 49.3%), D. melanogaster DIAP2 (41.7% and 46.6%), Bombyx mori IAP (53.5% and 58.9%), H. sapiens c-IAP1 (43.1% and 50.7%), M. musculus c-IAP1 (43.1% and 50.7%), C. gigas (36.1% and 57.5%), and Penaeus monodon IAP (40.5% and 50.7%) (Fig. 1b). To evaluate the evolutional relationship of EsIAP1, a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the amino acid sequences of 13 IAP members by the neighbor-joining method. EsIAP1 was firstly clustered with other arthropod IAPs in the phylogenetic tree, and then grouped with invertebrate IAPs, and finally clustered into the vertebrate XIAPs and c-IAPs (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

The sequence characteristics and phylogeny of EsIAP1. (a) The predicted structural domain of EsIAP1, which contains two BIR domains. (b) Multi-sequence alignment the amino acids sequences of BIR1 and BIR2 domains among IAP family members. The species and the GenBank accession numbers are as follows: Homo sapiens c-IAP1 (Q13490.2), Mus musculus c-IAP1 (Q62210.1), H. sapiens c-IAP2 (Q13489.2), M. musculus c-IAP2 (O08863.2), M. musculus XIAP (AAB58376.1), H. sapiens XIAP (AAC50373.1), Litopenaeus vannamei IAP1 (ADH03018.1), Bombyx mori IAP (NP_001037024), Penaeus monodon IAP (NP_001037024.), Crassostrea gigas IAP1 (AEB54799.1), and Drosophila melanogaster DIAP2 (Q24307.3). Conserved cysteine and histidine residues of EsIAP1 are marked with “▼”. Other conserved, but not consensus amino acids are shaded in gray. (c) The unrooted tree was built based on the amino acid sequences of 13 IAP family members. The species and the GenBank accession numbers were as follows: H. sapiens c-IAP1 (Q13490.2), M. musculus c-IAP1 (Q62210.1), H. sapiens c-IAP2 (Q13489.2), M. musculus c-IAP2 (O08863.2), M. musculus XIAP (AAB58376.1), H. sapiens XIAP (AAC50373.1), L. vannamei IAP1 (ADH03018.1), L. vannamei IAP2 (ADY38394.1), P. monodon IAP (ABO38431.1), Danio rerio XIAP (AAI33127.1), B. mori IAP (NP_001037024), D. melanogaster DIAP1 (Q24306.2) and E. sinensis IAP1 (AWK27045).

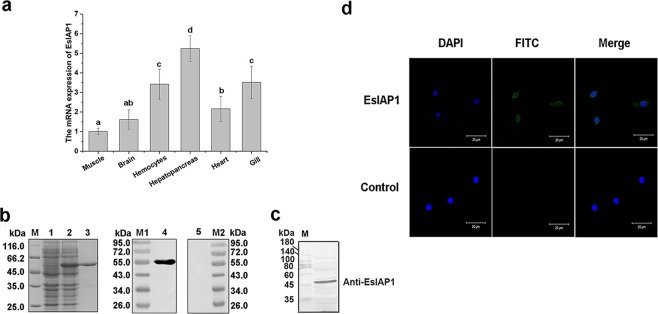

Tissue distribution of EsIAP1 mRNA and subcellular localization of EsIAP1 in hemocytes

The mRNA transcripts of EsIAP1 could be detected in all the examined tissues, including hemocytes, hepatopancreas, heart, gill, brain and muscle with the highest expression level in hepatopancreas, which was 5.24-fold (p < 0.01) of that in muscle. The expression level of EsIAP1 mRNA in gill, hemocytes, heart and brain was 3.51-fold (p < 0.01), 3.41-fold (p < 0.01), 2.16-fold (p < 0.05) and 1.61-fold (p > 0.05) of that in muscle, respectively (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2.

The mRNA expression of EsIAP1 in crabs and subcellular localization of EsIAP1 in hemocytes. (a) Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of the expression level of EsIAP1 mRNA in different tissues. The different letters show that there exist significant differences comparing with other groups (p < 0.05). (b) SDS-PAGE and western blotting analysis of rEsIAP1. Lane M: protein marker; Lane 1: negative control for rEsIAP1 (without IPTG induction); Lane 2: IPTG induced rEsIAP1; Lane 3: purified rEsIAP1. Lane M1: protein marker; Lane 4: western blotting analysis of the rEsIAP1; Lane 5: western blotting analysis of the pre-immune serum from mice; Lane M2: protein marker. (c) The specific antibody detection of native EsIAP1. (d) Localization of EsIAP1 in hemocytes. Immunohistochemistry was performed to analyze the expression of EsIAP1 in hemocytes of E. sinensis. After incubation of polyclonal antibody of EsIAP1 or pre-immune serum (negative control), Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat-anti-mouse antibody was used to detect EsIAP1. Nucleus was stained with DAPI (blue). Positive signals of EsIAP1 were shown in green. Scale bar = 20 μm. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

The purified rEsIAP1 was employed to prepare polyclonal antibody (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. S1). A clear band with 55 kDa was revealed by western blotting assay, indicating the high recognition specificity of the polyclonal antibody against EsIAP1 (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. S1). Pre-immune serum was used as negative control and no bands were detected (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. S1). Western blotting assay of the native tissue sample with EsIAP1 antibody revealed that there was a distinct band of 50 kDa (Fig. 2c). Immunofluorescence assay was performed to detect the localization of EsIAP1 in hemocytes. The nucleus stained by DAPI was observed in blue, and the positive signal of EsIAP1 was in green. The positive fluorescence signals were mainly observed in the cytoplasm of hemocytes according to the merged pictures (Fig. 2d).

The expression of EsIAP1 mRNA in hemocytes after LPS and A. hydrophila stimulations

The expression level of EsIAP1 mRNA in hemocytes increased significantly after the stimulations with LPS and A. hydrophila. After LPS stimulation, the mRNA transcripts of EsIAP1 increased significantly at 12 h (2.80-fold compared with that in PBS group, p < 0.01), reached the highest level of 13.86-fold (p < 0.01) at 24 h, and finally down-regulated to 2.44-fold (p < 0.01) at 48 h (Fig. 3a). After A. hydrophila stimulation, the relative expression level of EsIAP1 mRNA kept at quite low level and there was no significant difference from 0 to 24 h compared with that in PBS group. However, it increased significantly (2.71-fold of control group, p < 0.01) at 48 h post A. hydrophila stimulation (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Temporal expression of the EsIAP1 transcripts in hemocytes after LPS and A. hydrophila stimulations. (a) qRT-PCR detection of the expressions of EsIAP1 in crabs challenged by LPS. (b) qRT-PCR detection of the expressions of EsIAP1 in crabs challenged by A. hydrophila.

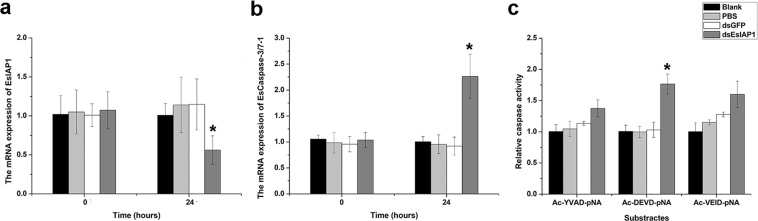

The mRNA expression of EsCaspase-3/7-1 and the activity of caspases in hemocytes after the gene silencing of EsIAP1

To further explore the function of EsIAP1 in vivo, the dsRNA-induced RNA interference (RNAi) was used to inhibit the expression of EsIAP1. The mRNA expression of EsIAP1 in hemocytes decreased to 0.47-fold (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4a), while the mRNA expression of EsCaspase-3/7-1 increased to 2.26-fold (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4b) at 24 h post the injection with sequence-specific dsRNA targeting EsIAP1 compared to that in dsGFP group. After EsIAP1 was silencd, the activity of caspase towards Ac-DEVD-pNA in hemocytes increased to 1.71-fold (p < 0.05) compared to that in the dsGFP group. While the activity of caspase-1 towards Ac-YAVD-pNA and caspase-6 towards Ac-VEID-pNA in hemocytes increased to 1.21-fold (p > 0.05) and 1.25-fold (p > 0.05) of that in the dsGFP group, respectively (Fig. 4c).

Figure 4.

The mRNA and activity of caspase after the gene silencing of EsIAP1. (a) The expression level of EsIAP1 mRNA in hemocytes after gene silencing of EsIAP1. Comparison of the level of EsIAP1 was normalized to dsGFP group. (b) The expression level of the EsCaspase-3/7-1 mRNA in hemocytes of EsIAP1-interfered crabs. Comparison of the level of EsIAP1 was normalized to dsGFP group. (c) The activities of caspases were determined by measuring hydrolyzing activity against Ac-YVAD-pNA (substrate of caspase-1), Ac-DEVD-pNA (substrate of caspase-3) or Ac-VEID-pNA (substrate of caspase-6).

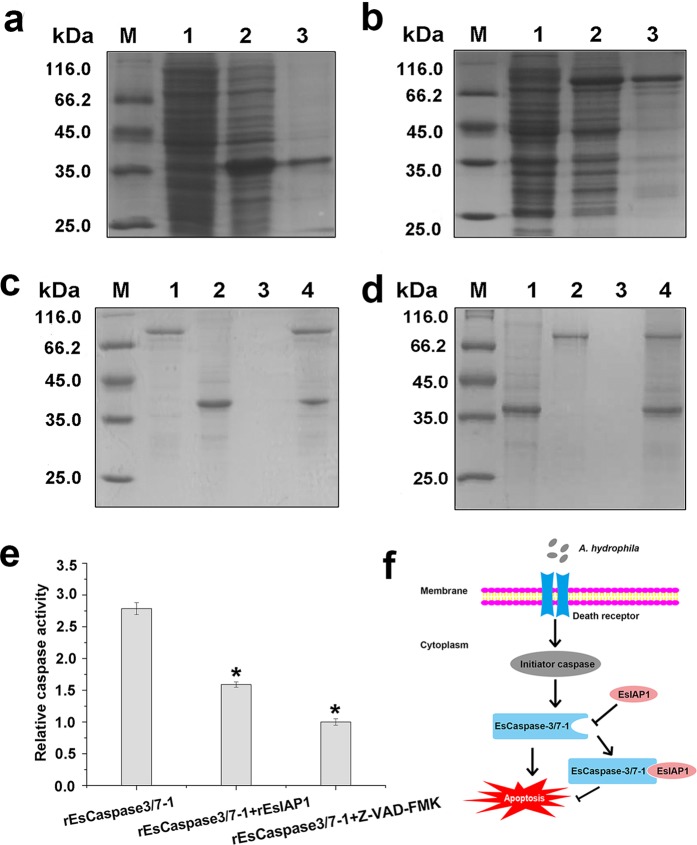

The interation of rEsIAP1 with rEsCaspase-3/7-1 in vitro

The interaction of EsIAP1 with EsCaspase-3/7-1 was analyzed by pull down assay to understand the regulatory mechanism of apoptosis. The full-length ORFs of EsIAP1 and EsCaspase-3/7-1 were expressed, and the purified rEsIAP1 and rEsCaspase-3/7-1 (Fig. 5a-b, Supplementary Fig. S2a-b) were used for GST and His pull down assays. Two distinct bands were observed in the elute liquid after pull down assay (Fig. 5c-d, Supplementary Fig. S2c-d). The results indicated that rEsIAP1 could directly combine and interact with rEsCaspase-3/7-1 in vitro.

Figure 5.

Interaction between EsIAP1 and EsCaspase-3/7-1 in vitro. (a) Purified rEsCaspase-3/7-1 (His). Lane 1: negative control for rEsCaspase-3/7-1 (His) (without IPTG induction); Lane 2: IPTG induced rEsCaspase-3/7-1 (His); Lane 3: purified rEsCaspase-3/7-1 (His). (b) Purified rEsIAP1 (GST). Lane 1: negative control for rEsIAP1 (GST, without IPTG induction); Lane 2: IPTG induced rEsIAP1 (GST); Lane 3: purified rEsIAP1 (GST). (c) Pull down by rEsIAP1 (GST). Lane 1: purified rEsIAP1 (GST); Lane 2: purified rEsCaspase-3/7-1 (His); Lane 3: washed liquid; Lane 4: eluted liquid. (d) Pull down by rEsCaspase-3/7-1 (His). Lane 1: purified rEsCaspase-3/7-1 (His); Lane 2: purified rEsIAP1 (GST); Lane 3: washed liquid; Lane 4: eluted liquid. (e) The activity of rEsIAP1 was detected with caspase-3 activity assay kit. (f) Model for EsIAP1 involvement in apoptosis pathway. A. hydrophila could activate caspase-mediated apoptosis pathway to initiate the activity of EsCaspase-3/7-1 to lead to hemocyte apoptosis. EsIAP1 could combine with EsCaspase-3/7-1 to inhibit the hemocyte apoptosis.

The hydrolytic activity of rEsCaspase-3/7-1 after incubation with rEsIAP1 in vitro

The hydrolyzing assay of caspase-3 substrate was employed to investigate the activity of rEsIAP1. The hydrolytic activity of rEsCaspase-3/7-1 was significantly inhibited after the incubation with rEsIAP1. rEsCaspase-3/7-1 displayed high hydrolytic activity towards Ac-DEVD-pNA (0.44 units per mg protein). After rEsCaspase-3/7-1 was incubated with rEsIAP1 or Z-VAD-FMK, the hydrolytic activities were 0.25 and 0.15 units per mg protein, respectively, which were significantly lower than that in rEsCaspase-3/7-1 group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5e).

Discussion

Apoptosis represents a fundamental biological process that relies on the activation of caspases34. IAPs are a family of negative regulators of both caspases and cell death35. In the present study, a novel IAP was identified from E. sinensis (designated EsIAP1). There were two BIR domains identified in EsIAP1, which was the typical domain of IAP family6. The deduced amino acid sequences of BIR1 and BIR2 domains in EsIAP1 shared high similarities (36.1%~53.5% and 45.9%~58.9%, respectively) with the corresponding domains of other IAP proteins (Fig. 1a,b). Moreover, the conserved spacing of cysteine and histidine residues (Cx2 Cx6 Wx3 Dx5 Hx6 C) in the other reported BIR2 domains were also found in EsIAP1, which was suggested to contribute to a novel zinc-binding fold6. These results suggested that EsIAP1 was a typical IAP family member. In the phylogenetic tree, EsIAP1 was firstly grouped with the crustacean IAPs to form a separated clade, then grouped with other arthropod IAP proteins, and finally clustered with vertebrate IAP proteins (Fig. 1c). These evidences collectively indicated that EsIAP1 belonged to the IAP family in crustaceans.

As regulators of the apoptotic machinery, IAPs play important roles in many physiological processes, including homeostasis maintenance, development of tissues, and immune responses22,36,37. In the present study, the mRNA transcripts of EsIAP1 could be detected in all the examined tissues inculding hemocytes, hepatopancreas, gill, muscle, brain, and heart (Fig. 2a). Similarly, the transcripts of CgIAP2 were also detected in various tissues in oyster C. gigas25. The constitutive expression profile of EsIAP1 indicated that it might involve in many physiological processes of crabs. It has been reported that IAPs could regulate the activity of caspases, further modulate cell cycle proliferation and receptor-mediated signal transduction9. The higher level of EsIAP1 mRNA was observed in immune-associated tissues, including hemocytes, hepatopancreas and gill, which might be attributed to the cellular metabolism and innate immunity38,39. Crustacean hemocytes play important roles in the host immune response, including recognition, phagocytosis and cell communication33,40,41. Moreover, the high level of EsCaspase-3/7-1 and EsCaspase-3-like were observed in hemocytes28,29. The hemocytes were thus chosen as target to analyze the expression of EsIAP1. In the present study, the location of EsIAP1 in hemocytes was observed by immunofluorescence assay, and the positive signal was found to be mainly distributed in the cytoplasm, which was similar as the previous reports in other species42–45, possibly for the sake of binding to cytoplasmic caspase to regulate hemocyte apoptosis. LPS, a vital component of the outer wall of gram-negative bacteria, could trigger caspase-mediated apoptosis pathway42,46. The apoptosis pathway is regulated by initiator caspases (such as aspase-8 and caspase-10), which can be triggered by death receptor (like Fas, TNFR1 and TRAIL-R1/R2) to initiate the activity of effector caspases43–45. In the present study, the expression level of EsIAP1 mRNA was significantly up-regulated after LPS and A. hydrophila stimulations (Fig. 3a,b). It has been reported that apoptosis pathway could be activated after LPS and A. hydrophila stimulations in crustacean47,48. In C. gigas, CgIAP2 was proposed to play a role in apoptosis inhibition in the immune defense against bacterial challenge25. Some crustacean IAPs such as PmIAP and LvIAP1 were suggested to be central to the regulation of hemocyte apoptosis24,49. Theses results suggested that EsIAP1 might exert important roles in immune defenses by regulating the apoptosis pathway in E. sinensis.

IAPs could regulate apoptosis through controlling caspase activities and caspase-activating platform formations, which also appeared to be important determinants of the responses of cells to endogenous or exogenous cellular injuries13. It was reported that c-IAP1 and c-IAP2 could directly bind to the activated caspase-3 and -7 to inhibit their activities in vertebrates10. In the present study, EsCaspase-3/7-1, an effector caspase, identified previously from E. sinensis28, were employed to investigate the binding activity of EsIAP1 with caspase. After rEsCaspase-3/7-1 was incubated with rEsIAP1 or Z-VAD-FMK, the hydrolyzing activity of rEsCaspase-3/7-1 was significantly decreased (Fig. 5e). This result was in coincidence with the observation that IAPs could inhibit the activation of effctor caspase13,20. The direct combination of rEsIAP1 with rEsCaspase-3/7-1 confirmed by pull down assay might explain the decrease of rEsCaspase-3/7-1 hydrolyzing activity after incubation with rEsIAP1 in vitro. These results suggested that rEsIAP1 could inhibit the hydrolytic activity of rEsCaspase-3/7-1 by interacting with rEsCaspase-3/7-1. Furthermore, the expression of EsCaspase-3/7-1 mRNA in hemocytes of crabs were significantly increased after the interference of EsIAP1, indicating the inhibitory regualtion of EsIAP1 on EsCaspase-3/7-1. The hydrolytic activity of caspase-3 was increased in hemocytes rather than caspase-1 and -6 after EsIAP1 was silenced. These results showed that EsIAP1 could regulate EsCaspase-3/7-1 and further inhibit hemocyte apoptosis in vivo. Similarly, the number of circulating hemocytes was increased in LvIAP1-silenced shrimp because of the extensive apoptosis24. Some mammalian IAPs, such as c-IAP1 and c-IAP2, were also found to be involved in signaling cascades, and play important roles in TNF-induced apoptosis50. Therefore, it was speculated that EsIAP1 could inhibit apoptosis by regulating EsCaspase-3/7-1 in E. sinensis.

Caspases are activated to gain the full catalytic activity after being proteolytically cleaved to initiate apoptosis51. EsCaspase-3, -7 and -8 are characterized to play crucial roles in Cadmium-induced apoptosis27, and EsCaspase-3/7-1 and EsCaspase-3-like protein are found to be involved in innate immune response and induce apoptosis under pathogen stimulation28,29. IAPs inhibit such proteolytically activated caspases, and further regulate apoptosis52. The loss or inhibition of cIAP1, cIAP2 and XIAP causes the majority of cells to be sensitized to death receptor to induce cell death53. In Drosophila, DIAP1 normally inhibits both initiator and effector caspases54,55. In summary, this study suggested that LPS and bacterial challenge could activate the apoptosis pathway in E. sinensis. EsIAP1 could inhibit apoptosis by directly combining with EsCaspase-3/7-1 and inhibit its hydrolytic activity (Fig. 5f). These results provided novel idea to understand the modulatory role of IAP in apoptosis pathway in crustaceans.

Materials and Methods

Crabs, collection of tissues and immune stimulations

The crabs with an average weight of 20 g were collected from a commercial farm in Lianyungang, China, and cultured in aerated freshwater at 20 ± 2 °C for one week before processing28. Six crabs were sacrificed for determining the expression of EsIAP1 mRNA in different tissues. The tissues including muscle, heart, brain, hepatopancreas and gill were collected from crabs to detect the mRNA expression of EsIAP1 according to the previous study56. The hemolymph drawing from the last pair of walking legs from each crab by using a syringe was mixed with anticoagulant solution (510 mM NaCl, 100 mM glucose, 200 mM citric acid, 30 mM sodium citrate, 10 mM EDTA·2Na, pH 7.3) at a ratio of 1:1, and the hemocytes were harvested by centrifugation57. Tissues from two crabs were pooled together as one sample and there were three duplicates for each assay according to the previous methods58. The crabs were treated by the injections of 100 μL Aeromonas hydrophila (107 CFU mL−1) and 100 μL lipopolysaccharide (500 μg mL−1) according to the previous reports59, respectively. Ninety crabs were employed and randomly divided into three groups. According to previous study, a volume of 100 μL alive A. hydrophila (1 × 107 CFU mL−1) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS from Escherichia coli 0111:B4, L2630, Sigma Aldrich, USA; 100 µg mL−1) resuspending in PBS (40 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4) was injected into the arthrodial membrane of the last pair of walking legs in the stimulation groups, respectively28,59,60. The crabs received an injection of 100 µL PBS were employed as control group. Six crabs were randomly sampled from each group at 0, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h after treatments.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) was uesd for the extraction of total RNA from E. sinensis tissue samples, and the first-strand cDNA was synthesised by using the PrimeScript™ real-time PCR kit (Takara, Japan) according to the manufacture’s instruction.

Sequence analysis of EsIAP1

The sequence of IAP genes was analyzed by BLASTP (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) in the genome database (PRJNA305216) of E. sinensis61. The primers (EsIAP1-F and -R) were designed to clone the open reading frame (ORF) of EsIAP1. The multiple sequence alignments were created by Clustal W. The conserved domain was identified through the SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/). MEGA6.0 package was used to construct phylogenetic tree.

Purification of recombinant protein and preparation of polyclonal antibody

The full-length ORF sequences of EsIAP1 and EsCaspase-3/7-1 were amplified with specific primers (rEsIAP1-His-F and -R, rEsCaspase-3/7-1-F and -R) (Table 1). The PCR products were inserted into pET-22b vector (Novagen) with a His-tag. rEsIAP1-GST-F and -R (Table 1) were used to amplify EsIAP1, and the PCR products were inserted into the pGEX4T-1 vector (GE Healthcare) with a GST-tag. All those recombinant plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3) competent cells. These prokaryotic proteins were purified by a Ni2+ chelating sepharose column or GST-resin, following the manufacturers’ instructions. Their concentrations were measured by BCA kit (Beyotime). The preparation of antiserum was performed as previously described62.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study.

| Primers | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| EsIAP1-F | ATGGACATGTCTCGTCGGCAGTT |

| EsIAP1-R | TCAGCCGATGATGGGCCG |

| rEsCaspsase-3/7-1-F | GGGAATTCCATATGGATAACATCAAGGAAAATGG |

| rEsCaspsase-3/7-1-R | CCGCTCGAGATACTTGGGAGACAGGAAGACCT |

| rEsIAP1-F (His) | GGAATTCCATATGGACATGTCTCGGCAGTT |

| rEsIAP1-R (His) | CCGCTCGAGGCCGATGATGGGCCG |

| rEsIAP1-F(GST) | CGCGGATCCATGGACATGTCTCGGCAGTT |

| EsIAP1-R(GST) | ACGCGTCGACGCCGATGATGGGCCG |

| EsIAP1-RNAi-F | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATGGACATGTCTCGTCGGCAGTT |

| EsIAP1-RNAi-R | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGCCGATGATGGGCCG |

| GFP-RNAi-F | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGACGTAAACGGCCACAAGT |

| GFP-RNAi-R | TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGC |

| EsIAP1-qRT-F | CGCCAGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC |

| EsIAP1-qRT-R | CATCAAGGAGAAACTGTGCT |

| EsCaspsase-3/7-1-qRT-F | CCACCACTGCTGACTTCTTGATA |

| EsCaspsase-3/7-1-qRT-R | AGACAGGAAGACCTTTCTCATCAA |

| Es-β-Actin-F | CCCATCTACGAGGGCTACGC |

| Es-β-Actin-R | CCTTGATGTCTCGCACGATTTCT |

Western blotting and immunohistochemistry analysis of EsIAP1

The western blotting assay was performed according to the previous report28. Recombinant protein was separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking for 1 h with 5% non-fat milk in TBST, the membrane was incubated successively with 1/1000 diluted poly-antibody of anti-EsIAP1 as first antibody and 1/10,000 diluted goat-anti-mouse IgG (Sangon) as secondary antibody. After washing in TBST, the membrane dipped in ECL substrate system (Thermo Scientific) for 2 min, then imaged by Amersham Imager 600 (General Electric Company).

The hemocytes were resuspended with DMEM (Sangon) and then added into poly-L-lysine pre-coated dishes. After fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, diluted in PBS), the dishes were blocked with 3% fetal bovine serum albumin (diluted in PBS) at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by washing with PBST (PBS with 0.1% tween-20). The dishes were then successively incubated with 1/1000 diluted anti-EsIAP1 antibody at 37 °C for 1 h and 1/1,000 diluted Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat-anti-mouse antibody at 37 °C for 1 h. After final washing with PBST, DAPI (1 µg/mL in PBS) was used to stain the nucleus, and the dishes were observed by fluorescence microscope (ZEISS).

RNA interference

The RNA interference assay of EsIAP1 was performed according to the previous report32. T7 promoter linked primers (GFP-RNAi-F and -R, EsIAP1-RNAi-F and -R) were used to amplify the cDNA sequence of dsGFP (657 bp) and dsEsIAP1 (1,356 bp), respectively. The dsRNAs of EsIAP1 and GFP were diluted with PBS to the final concentration of 0.5 μg μL−1. The crabs were treated by the injections with 100 μL PBS, dsGFP and dsEsIAP1, respectively. The untreated crabs were used as blank group. Six crabs from each group were randomly sampled at 0 and 24 h post injections. The hemocytes were divided into two parts, and one aliquot of hemocyte sample was used to estimate the silencing efficiency, while the other was used for the measurment of caspase activity.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of mRNA expression

qRT-PCR was conducted according the previous reports63. Two primers, EsIAP1-qRT-F and -R, were used in qRT-PCR to detect the expression of EsIAP1. The fragment amplified by primers of Es-β-actin (Es-β-Actin-F and -R) were employed as reference. The gene expression analysis was performed using the 2−∆∆Ct method63, and all data were given in terms of relative mRNA expression of mean ± S.E. (N = 3).

Pull down assay

The pull down assay was carried out according to the previous report63. The proteins of rEsIAP1 (GST) and rEscaspase-3/7-1 (His) (30 μg) were mixed with 20 μL of glutathione resin (for GST-tagged proteins) or charged nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (for His-tagged proteins), respectively. The mixture (resin and binding proteins) was incubated at room temperature for 2 h with slight rotation, and then washed for three times by centrifuging at 500 × g for 3 min to remove the unbound proteins. The tested protein (rEsCaspase-3/7-1-His and rEsIAP1-GST), without GST tag or His tag, was added into the mixture containing the nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads or glutathione resin, and gently rotated at room temperature for 2 h. After washing three times, the mixture was analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

The hydrolyzing function assays of rEsIAP1 in vitro

The potential inhibiting hydrolytic activity of rEsIAP1 was detected using the caspase-3 activity assay kit (Beyotime) under the manufacturer’s manual10. The protein concentration of purified rEsIAP1-His and rEsCaspase-3/7-1 was adjusted to 1 mg mL−1. There were three experimental grous, including blank group (rEsCaspase-3/7-1), rEsIAP1 group (rEsIAP1 + rEsCaspase-3/7-1), and Z-VAD-FMK (pan caspase inhibitor) group (Z-VAD-FMK + rEsCaspase-3/7-1). rEsCaspase-3/7-1 protein in rEsIAP1 and Z-VAD-FMK groups were pre-incubated with rEsIAP1 and Z-VAD-FMK at final concentrations of 100 μg mL−1 and 100 μM, respectively64. The mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h and absorbance value was monitored at 405 nm by the SpectraMax 190 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The blank group (rEsCaspase-3/7-1) was employed as the control, and the hydrolytic activity of rEsIAP1 was determined by comparing the hydrolytic activity of rEsCaspase-3/7-1 against Ac-DEVD-pNA.

Hydrolyzing activity analysis of caspases in EsIAP1-interfered crabs

The hydrolyzing activity of caspases in hemocytes was examined according to the method described by previous study29. The hydrolytic activity of the crab hemocyte protein was detected at 0 and 24 h after the injection of EsIAP1-dsRNA. The protein concentration of the supernatant was measured using the Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime) and adjusted to 1 mg mL−1 with lysate buffer. The hydrolytic activity of caspases was examined with the substrate Ac-YAVD-pNA, Ac-DEVD-pNA and Ac-VEID-pNA using the caspase-1, -3 and -6 activity assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) under the manufacturer’s manual. The absorbance values of the reaction mixture was monitored at 405 nm using Spectra Max 190 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The different absorbance values represented the cleavage and release of pNA. The blank group was used as the reference.

Statistical analysis

The data (represented as mean ± S.E., N = 3) were calculated by using the 2−∆∆Ct method65, and analyzed with t-test. Significant differences across controls were indicated with an asterisk at p < 0.05, and two asterisks at p < 0.01.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the laboratory members for their technical advice and helpful discussions. We also thank Jiong Chen for helpful suggestions. This research was supported by National Key R&D Program (2018YFD0900606), NSFC (No. 31530069), AoShan Talents Cultivation Program Supported by Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (No. 2017ASTCP-OS13), Dalian High Level Talent Innovation Support Program (2015R020), Program for Innovative Talents in Higher Education of Liaoning Province (LR2016036), the Research Foundation for Distinguished Professor in Liaoning (to L. S.) and Talented Scholars in Dalian Ocean University (to L. W.).

Author contributions

C.Q. prepared the experiments and figures. Experiments were assisted by J.-J.S., Q.-S. X., X.-J.L., W.Y., F.-F.W., Y.W., Q.-L.Y., Z.-H.J., L.-L.W. and L.-S.S. supervised the work. The manuscript was written by C.Q., J.-J.S. and edited by L.-S.S.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-56971-1.

References

- 1.Steller H. Mechanisms and genes of cellular suicide. Science. 1995;267:1445–1449. doi: 10.1126/science.7878463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kiss T. Apoptosis and its functional significance in molluscs. Apoptosis. 2010;15:313–321. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0446-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danial NN, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death: critical control points. Cell. 2004;116:205–219. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fan TJ, Han LH, Cong RS, Liang J. Caspase family proteases and apoptosis. Acta Bioch. Bioph. Sin. 2005;37:719–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7270.2005.00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Youle RJ, Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deveraux QL, Reed JC. IAP family proteins-suppressors of apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:239–252. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crook NE, Clem RJ, Miller LK. An apoptosis-inhibiting baculovirus gene with a zinc finger-like motif. J. Virol. 1993;67:2168–2174. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2168-2174.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Riordan MX, Bauler LD, Scott FL, Duckett CS. Inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in eukaryotic evolution and development: a model of thematic conservation. Dev. Cell. 2008;15:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang YL, Li XM. The IAP family: endogenous caspase inhibitors with multiple biological activities. Cell Res. 2000;10:169–177. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natalie R, Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. The c-IAP-1 and c-IAP-2 proteins are direct inhibitors of specific caspases. EMBO J. 1997;23:6914–6925. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death proteases. Nature. 1997;388:300–304. doi: 10.1038/40901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamm I, et al. IAP-family protein Survivin inhibits caspase activity and apoptosis induced by Fas (CD95), Bax, Caspases, and anticancer drugs. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5315–5120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berthelet J, Dubrez L. Regulation of apoptosis by inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) Cell. 2013;2:163–187. doi: 10.3390/cells2010163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi R, et al. A single BIR domain of XIAP sufficient for inhibiting caspases. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:7787–7790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borden KL. RING domains: master builders of molecular scaffolds. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;295:1103–1112. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liston P, Fong WG, Korneluk RG. The inhibitors of apoptosis: there is more to life than Bcl2. Oncogene. 2003;22:8568–8580. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin H, et al. The BIR domain of IAP-like protein 2 is conformationally unstable: implications for caspase inhibition. Biochem. J. 2005;385:1–10. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ditzel M, Meier P. IAP degradation decisive blow or altruistic sacrifice. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:449–542. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(02)02366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaux DL, Silke J. IAPs, RINGs and ubiquitylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:287–297. doi: 10.1038/nrm1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meier P, Silke J, Leevers SJ, Evan GI. The Drosophila caspase DRONC is regulated by DIAP1. EMBO J. 2000;19:598–611. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muro I, Hay BA, Clem RJ. The Drosophila DIAP1 protein is required to prevent accumulation of a continuously generated, processed form of the apical caspase DRONC. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:49644–49650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203464200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gesellchen V, Kuttenkeuler D, Steckel M, Pelte N, Boutros M. An RNA interference screen identifies inhibitor of apoptosis protein 2 as a regulator of innate immune signalling in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:979–984. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kleino A, et al. Inhibitor of apoptosis 2 and TAK1-binding protein are components of the Drosophila Imd pathway. EMBO J. 2005;24:3423–3434. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leu JH, et al. Litopenaeus vannamei inhibitor of apoptosis protein 1 (LvIAP1) is essential for shrimp survival. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2012;38:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qu T, et al. Characterization of an inhibitor of apoptosis protein in Crassostrea gigas clarifies its role in apoptosis and immune defense. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2015;51:74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang LL, Li L, Zhang GF. Gene discovery, comparative analysis and expression profile reveal the complexity of the Crassostrea gigas apoptosis system. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011;35:603–610. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu YR, Yang WX. Role of three EsCaspases during spermatogenesis and Cadmium-induced apoptosis in Eriocheir sinensis. Aging. 2018;10:1146–1165. doi: 10.18632/aging.101454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qu C, et al. A novel effector caspase (Caspase-3/7-1) involved in the regulation of immune homeostasis in Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018;83:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2018.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu MH, et al. Caspase-mediated apoptosis in crustaceans: cloning and functional characterization of EsCaspase-3-like protein from Eriocheir sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014;41:625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2014.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang PH, et al. Analysis of expression, cellular localization, and function of three inhibitors of apoptosis (IAPs) from Litopenaeus vannamei during WSSV infection and in regulation of antimicrobial peptide genes (AMPs) PLoS One. 2013;8:e72592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, et al. Genetic improvement and breeding practices for Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 2018;49:292–301. doi: 10.1111/jwas.12500. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dong CH, et al. The immune responses in Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis challenged with double-stranded RNA. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2009;26:438–442. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johansson MW, Keyser P, Sritunyalucksana K, Soderhall K. Crustacean haemocytes and haematopoiesis. Aquaculture. 2000;191:45–52. doi: 10.1016/S0044-8486(00)00418-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obexer P, Ausserlechner MJ. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein-a critical death resistance regulator and therapeutic target for personalized cancer therapy. Front. Oncol. 2014;4:197. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott FL, et al. XIAP inhibits caspase-3 and -7 using two binding sites: evolutionarily conserved mechanism of IAPs. EMBO J. 2005;24:645–655. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xing Z, Conway EM, Kang C, Winoto A. Essential role of survivin, an inhibitor of apoptosis protein, in T cell development, maturation, and homeostasis. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:69–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cai Q, et al. A potent and orally active antagonist (SM-406/AT-406) of multiple inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) in clinical development for cancer treatment. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:2714–2726. doi: 10.1021/jm101505d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lavine MD, Strand MR. Insect hemocytes and their role in immunity. Insect Biochem. Molec. 2002;32:1295–1309. doi: 10.1016/S0965-1748(02)00092-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao ZY, et al. Profiling of differentially expressed genes in hepatopancreas of white spot syndrome virus-resistant shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) by suppression subtractive hybridisation. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2007;22:520–534. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bachere E, et al. Knowledge and research prospects in marine mollusc and crustacean immunology. Aquaculture. 1995;132:17–32. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(94)00389-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adachi K, Hirata T, Nishioka T, Sakaguchi M. Hemocyte components in crustaceans convert hemocyanin into a phenoloxidase-like enzyme. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2003;134:135–141. doi: 10.1016/S1096-4959(02)00220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi KB, et al. Lipopolysaccharide mediates endothelial apoptosis by a FADD-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:20185–20188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ye J, et al. Protective effect of SIRT1 on toxicity of microglial-derived factors induced by LPS to PC12 cells via the p53-caspase-3-dependent apoptotic pathway. Neurosci. Lett. 2013;553:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ding XM, Ding WX. Death receptor activation-induced hepatocyteapoptosis and liver injury. Curr. Mol. Med. 2003;6:491–508. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elmore S. Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007;35:495–516. doi: 10.1080/01926230701320337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen GM. Caspases: the executioners of apoptosis. Biochem. J. 1997;326:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3260001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xian JA, Miao YT, Li B, Guo H, Wang AL. Apoptosis of tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) haemocytes induced by Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2013;164:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu HS, et al. Effect of lipopolysaccharide on the hemocyte apoptosis of Eriocheir sinensis. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 2015;16:971–979. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1500098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leu JH, Kuo YC, Kou GH, Lo CF. Molecular cloning and characterization of an inhibitor of apoptosis protein (IAP) from the tiger shrimp, Penaeus monodon. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2008;32:121–133. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Varfolomeev E, et al. IAP antagonists induce autoubiquitination of c-IAPs, NF-kappaB activation, and TNFalpha-dependent apoptosis. Cell. 2007;131:669–681. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vasudevan D, Ryoo H. Regulation of cell death by IAPs and their antagonists. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2015;114:185–208. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shapiro PJ, Hsu HH, Jung H, Robbins ES, Ryoo HD. Regulation of the Drosophila apoptosome through feedback inhibition. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008;10:1440–1446. doi: 10.1038/ncb1803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vasilikos L, Spilgies LM, Knop J, Wong WW. Regulating the balance between necroptosis, apoptosis and inflammation by inhibitors of apoptosis proteins. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2017;95:160–165. doi: 10.1038/icb.2016.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tenev T, et al. The Ripoptosome, a signaling platform that assembles in response to genotoxic stress and loss of IAPs. Mol. Cell. 2011;43:432–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan N, Wu JW, Chai J, Li W, Shi Y. Molecular mechanisms of DrICE inhibition by DIAP1 and removal of inhibition by Reaper, Hid and Grim. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:420–428. doi: 10.1038/nsmb764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang W, et al. Beclin-1 is involved in the regulation of antimicrobial peptides expression in Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019;89:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang W, et al. A novel nuclear factor Akirin regulating the expression of antimicrobial peptides in Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2019;101:103451. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2019.103451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qu C, et al. The involvement of suppressor of cytokine signaling 6 (SOCS6) in immune response of Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2018;72:502–509. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2017.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jin XK, et al. Two novel short C-type lectin from Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis, are induced in response to LPS challenged. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2012;33:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jia ZH, Wang MQ, Wang XD, Wang LL, Song LS. The receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1) functions in hematopoiesis through JNK activation in Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016;57:252–261. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Song LS, et al. Draft genome of the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Gigascience. 2016;5:5. doi: 10.1186/s13742-016-0112-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheng SF, Zhan WB, Xing J, Sheng XZ. Development and characterization of monoclonal antibody to the lymphocystis disease virus of Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus isolated from China. J. Virol. Methods. 2006;135:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun JJ, et al. beta-Arrestins negatively regulate the Toll pathway in shrimp by preventing dorsal translocation and inhibiting Dorsal transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:7488–7504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.698134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu JC, et al. Caspase-3 serves as an intracellular immune receptor specific for lipopolysaccharide in oyster Crassostrea gigas. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2016;61:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2016.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using Real-Time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.