Abstract

Total medication burden (antihypertensive and non-antihypertensive medications) may be associated with poor systolic blood pressure (SBP) control. We investigated the association of baseline medication burden and clinical outcomes, and whether the effect of the SBP intervention varied according to baseline medication burden in the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial. Participants were randomized to intensive or standard SBP goal (below 120 or 140 mmHg, respectively); n=3,769 participants with high baseline medication burden (≥5 medications) and n=5,592 with low burden (<5 medications). Primary outcome: differences in SBP. Secondary outcomes: 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale, and modified Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medications measured at baseline and 12 months; and incident cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and SAEs throughout the trial. Participants in the intensive group with high versus low medication burden were less likely to achieve their SBP goal at 12 months (Relative Risk [RR] 0.91, 95%CI 0.85-0.97), but not in the standard group (RR 0.98, 95%CI 0.93, 1.03; Pinteraction<0.001). High medication burden was associated with increased CVD events (Hazard ratio [HR] 1.39, 95%CI 1.14-1.70) and SAEs (HR 1.34, 95%CI 1.24-1.45), but the effect of intensive versus standard treatment did not vary between medication burden groups (Pinteraction>0.5). Medication burden had minimal association with adherence or satisfaction. High baseline medication burden was associated with worse intensive SBP control and higher rates of CVD events and SAEs. The relative benefits and risks of intensive SBP goals were similar regardless of medication burden.

Keywords: hypertension, blood pressure, cardiovascular diseases, drug-related side effects and adverse reactions, medication adherence, patient satisfaction, polypharmacy

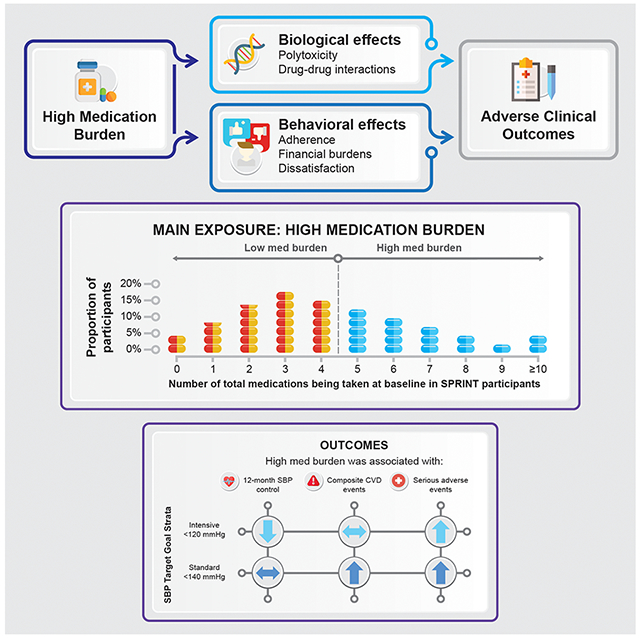

Graphical Abstract

Summary

Given the prevalence of hypertension among US adults, strategies are needed to reduce inappropriate medication burden among individuals treated for hypertension. Intensive SBP control remains a beneficial strategy to reduce CVD events regardless of medication burden status.

INTRODUCTION

Despite widespread availability of safe, effective, and low-cost antihypertensive medications, blood pressure (BP) control rates remain unacceptably low.1 High total daily medication burden, including antihypertensive and non-antihypertensive medications, may hinder control rates. Because achieving BP control often requires two or more antihypertensive medications, and hypertension often coincides with other comorbidities, patients with hypertension are likely to have high medication burden, often defined as taking five or more prescription medications.2 Although high medication burden may be clinically indicated and appropriate, it is associated with adverse events, medication non-adherence, reduced functional status, and other negative clinical outcomes.3–6

In the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT), targeting an intensive versus standard systolic BP (SBP) goal significantly reduced risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and all-cause mortality without negatively impacting patient-reported adherence, treatment satisfaction, and serious adverse events (SAEs).7,8 While the mean number of antihypertensive medications used per participant was 2.8 in the intensive group and 1.8 in the standard group, the association between total medication burden at baseline, including non-antihypertensive medications, and the likelihood of achieving and maintaining the assigned SBP goal within each treatment group is unknown.

We sought to determine the association between total prescription medication burden at baseline (including antihypertensive and non-antihypertensive medications) and SBP control, CVD events, SAEs, medication adherence, and treatment satisfaction. A secondary objective was to determine if total medication burden at baseline modified the effect of intensive vs standard treatment goals on CVD events and SAEs.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

In accordance with NIH policy, data will be shared through the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute data repository in spring 2019 (http://www.biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/home). The rationale, design, and primary results of SPRINT have been previously published.7,9 Briefly, SPRINT was a multicenter, randomized trial comparing two SBP treatment goals (an intensive goal of <120 mmHg versus a standard goal of <140 mmHg) in participants with hypertension at high CVD risk without diabetes or a history of stroke. Participants were age ≥50 years and had one or more high-CVD risk conditions (history of clinical or subclinical CVD other than stroke, estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] of 20–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 using the four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease [MDRD] equation,10 10-year risk for CVD ≥15% calculated using the Framingham Risk Score (FRS) for general clinical practice,11 and/or age ≥75 years). Those with diabetes, previous stroke, heart failure, proteinuria ≥1 g/day, or an eGFR <20 mL/min/1.73 m2 were excluded.

Trained SPRINT personnel ascertained participants’ baseline sociodemographic data, comorbidities,– and medications during the screening or randomization visit. We restricted the present analysis to participants with complete outcome and covariate data for each analysis (e.g., a participant with SBP data but missing adherence data at the 12-month visit would be included in the SBP analysis, but not the adherence analysis).

Each site’s institutional review board approved the main study protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Several agencies funded the trial without involvement in the analysis or interpretation of the present post-hoc study (see Acknowledgements). The SPRINT Steering Committee and Publications subcommittee reviewed and approved this manuscript on behalf of the SPRINT Research Group.

Assessment of Baseline Medication Burden

Trained study personnel recorded data on participants’ complete medication profiles (e.g., name, total daily dose) at baseline using information obtained from the participant, family member, or guardian (e.g., pill-bottle review), or if available, current medication profiles in the electronic health record (see Protocol and Supplemental Methods for description of data cleaning.)12 Medications were classified via route of administration, Food and Drug Administration-approved antihypertensive status, and over-the-counter status. Single-pill combinations were classified into individual components (e.g., “atorvastatin/amlodipine” was classified as two distinct components, “atorvastatin” and “amlodipine”). Each active ingredient in combination products were counted as individual medications because we could not reasonably determine if a combination product was used unless its brand name was recorded.

High medication burden was defined as five or more different prescription medications recorded at the baseline visit. There is no universally-accepted definition of “high” medication burden; however, five or more concomitantly-prescribed medications is frequently cited in the literature2,13,14 (see Supplemental Methods for detailed discussion.) The primary analysis included antihypertensive and non-antihypertensive prescriptions of all formulations and routes of administration, but to avoid exposure misclassification, we excluded over-the-counter medications and herbal supplements as these agents are inconsistently documented in medication reviews.15

Outcomes

We evaluated the following outcomes: 1) SBP, 2) CVD events (a composite of myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome not resulting in myocardial infarction, stroke, acute decompensated heart failure, or death from cardiovascular causes7,12), 3) all SAEs and SAEs of interest (i.e., hypotension, syncope, injurious falls, electrolyte abnormalities, or bradycardia7), 4) self-reported medication adherence scores measured by the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8),16–18 and 5) satisfaction with hypertension care and treatment using the modified Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM).19 SBP levels, medication adherence, and treatment satisfaction were evaluated at 12 and 48 months post-randomization. SBP levels were assessed in three ways: mean, mean change from baseline, and the proportion below the randomized treatment goal. Definitions, measurements, and adjudication of these outcomes have been previously described (see Supplemental Methods.)7–9,20

Covariates

Covariates were selected based on the potential to serve as confounders of the association between baseline total medication burden and the primary and secondary outcomes in the analysis, guided by clinical knowledge and prior evidence.5,21–23 Baseline covariates included age, sex, race or ethnic group, SBP, diastolic BP (DBP), eGFR, urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, blood glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, statin use, aspirin use, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), presence of metabolic syndrome, FRS, number of comorbidities, atrial fibrillation/flutter, myocardial infarction, heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, MMAS-8, treatment satisfaction scores, and depression. Definitions and measurement of these covariates have been previously described.7,9,20

Statistical Analysis

For the primary objective of determining the association between baseline medication burden and outcomes, analyses were performed within randomized treatment groups (i.e., intensive and standard). Modified Poisson regression with robust error variance was used to calculate risk ratios (RRs) for SBP control and to calculate adjusted percentages for medication adherence and treatment satisfaction associated with high or low baseline medication burden. Mean SBP and change in SBP from baseline to 12 months and 48 months was analyzed using an ordinary least squares regression model. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) for SAEs and CVD events associated with high or low baseline medication burden. The proportional hazards assumption was tested for violations by modeling the product of the medication burden group and the log of follow-up time as an interaction term. To determine the interaction between randomization treatment group and medication burden group, we calculated each outcome stratified by the randomized treatment group and included the product term (randomized treatment group×medication burden group) in each regression model in the full sample.

To determine if baseline medication burden modified the effect of intensive versus standard treatment, Cox proportional hazards regression was used to calculate HRs for CVD events and SAEs associated with intensive vs standard treatment within high or low baseline medication burden. The potential presence of an interaction between randomization treatment group and medication burden group was evaluated as described in the primary objective.

Several sensitivity analyses were planned for the present analysis a priori. To investigate whether the findings were sensitive to our medication burden definition, we repeated the analyses with various definitions: (1) including documented over-the-counter medications, (2) categorizing the number of baseline medications into ordinal categories and by quintiles, (3) excluding antihypertensive medications, and (4) restricting to only antihypertensives (by thresholds or tertiles). Because medication number is correlated with number of comorbidities, we repeated analyses stratified by the number of comorbidities at baseline, although number of comorbidities was included as a covariate in the primary analysis. Finally, two SAE sensitivity analyses were performed: first, we restricted the medication burden definition to non-antihypertensive medications only; and second, we restricted the outcome to only SAEs that the investigator deemed to be definitely or probably related to the treatment.

Adjusted percentages were calculated using STATA v.13.3 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX), and all other analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

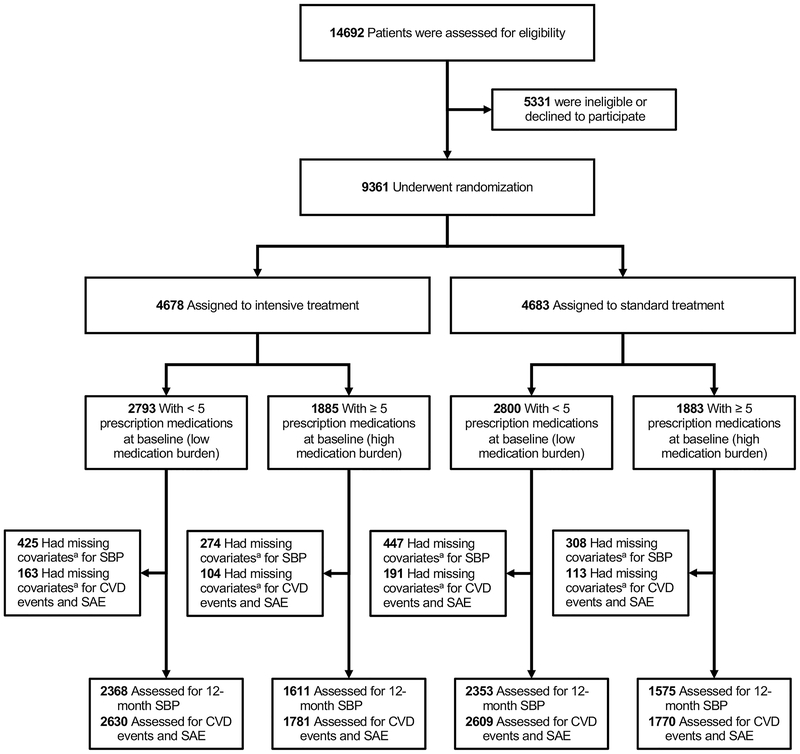

Among 9,361 study-eligible participants, 5,592 (59.7%) had low medication burden (median 3, IQR 2,4) and 3,769 (40.3%) had high medication burden (median 6, IQR 5,8) at baseline (Figure 1; Table S1 and Figures S1–S3 in the online-only data supplement). Those with high medication burden were more likely to be older, have lower SBP and DBP, demonstrate worse kidney function, use statins, and have more comorbidities at baseline compared to those with low medication burden (Table 1). These patterns were similar in the intensive and standard treatment groups (all Pinteraction>0.05).

Figure 1: CONSORT flow diagram.

CVD=cardiovascular disease; SAE=serious adverse event; SBP=systolic blood pressure

aMissing outcome or covariate data, see methods

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics by Treatment Group and Number of Baseline Medications

| Characteristic | Intensive treatment |

Standard treatment |

P interaction * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of baseline medications |

P-value | No. of baseline medications |

P-value | ||||

| < 5 | ≥ 5 | < 5 | ≥ 5 | ||||

| Participants, n | 2793 | 1885 | 2800 | 1883 | 0.93 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Age, years | 66.8±9.3 | 69.5±9.2 | <.001 | 66.9±9.5 | 69.3±9.3 | <.001 | 0.31 |

|

| |||||||

| Female sex | 998 (35.7) | 686 (36.4) | 0.64 | 977 (34.9) | 671 (35.6) | 0.60 | 0.97 |

|

| |||||||

| Race or ethnic group | <.001 | <.001 | 0.61 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Non-Hispanic black | 860 (30.8) | 519 (27.5) | 893 (31.9) | 530 (28.1) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Hispanic | 355 (12.7) | 148 (7.9) | 330 (11.8) | 151 (8.0) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1513 (54.2) | 1185 (62.9) | 1519 (54.3) | 1182 (62.8) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Other | 65 (2.3) | 33 (1.8) | 58 (2.1) | 20 (1.1) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Increased CVD risk criteria | 2352 (84.2) | 1708 (90.6) | <.001 | 2360 (84.3) | 1706 (90.6) | <.001 | 0.96 |

|

| |||||||

| Age ≥ 75 yr | 656 (23.5) | 661 (35.1) | <.001 | 699 (25.0) | 620 (32.9) | <.001 | 0.06 |

|

| |||||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 606 (21.7) | 723 (38.4) | <.001 | 601 (21.5) | 715 (38.0) | <.001 | 0.98 |

|

| |||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 394 (14.1) | 546 (29.0) | <.001 | 395 (14.1) | 542 (28.8) | <.001 | 0.93 |

|

| |||||||

| Clinical | 291 (10.4) | 448 (23.8) | <.001 | 275 (9.8) | 447 (23.7) | <.001 | 0.58 |

|

| |||||||

| Subclinical | 103 (3.7) | 98 (5.2) | 0.01 | 120 (4.3) | 95 (5.0) | 0.22 | 0.35 |

|

| |||||||

| FRS ≥ 15% | 2133 (76.9) | 1426 (75.7) | 0.37 | 2107 (75.8) | 1438 (76.7) | 0.49 | 0.26 |

|

| |||||||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 140.9±16.0 | 137.9±15.2 | <.001 | 140.7±15.2 | 138.1±15.5 | <.001 | 0.47 |

|

| |||||||

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 79.9±11.7 | 75.7±11.7 | <.001 | 79.8±11.9 | 75.4±11.7 | <.001 | 0.71 |

|

| |||||||

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 0.98 [0.84,1.15] | 1.04 [0.88,1.28] | <.001 | 0.99 [0.84,1.16] | 1.07 [0.89,1.29] | <.001 | 0.22 |

|

| |||||||

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 74.3 [62.3,86.3] | 66.4 [52.9,81.2] | <.001 | 73.9 [62.1,86.6] | 66.3 [52.5,80.4] | <.001 | 0.87 |

|

| |||||||

| Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio, g/mg | 9.0 [5.5,18.2] | 11.1 [6.1,28.3] | <.001 | 8.8 [5.4,18.7] | 10.7 [5.9,27.3] | <.001 | 0.42 |

|

| |||||||

| Blood glucose, mg/dL | 97.0 [90.0,105.0] | 98.0 [91.0,106.0] | 0.003 | 97.0 [91.0,104.0] | 98.0 [91.0,105.0] | 0.05 | 0.74 |

|

| |||||||

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 193.0 [169.0,221.0] | 176.0 [151.0,204.0] | <.001 | 194.0 [169.0,220.0] | 177.0 [153.0,205.0] | <.001 | 0.98 |

|

| |||||||

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL | 51.0 [43.0,61.0] | 50.0 [42.0,60.0] | 0.05 | 50.0 [43.0,61.0] | 50.0 [42.0,60.0] | 0.01 | 0.44 |

|

| |||||||

| Smoking status | <.001 | <.001 | 0.37 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Never | 1310 (46.9) | 743 (39.4) | 1320 (47.1) | 749 (39.8) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Former | 1058 (37.9) | 917 (48.6) | 1088 (38.9) | 910 (48.3) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Current | 414 (14.8) | 225 (11.9) | 380 (13.6) | 221 (11.7) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Missing | 11 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | |||

|

| |||||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.6±5.6 | 30.4±6.0 | <.001 | 29.5±5.6 | 30.3±5.9 | <.001 | 0.84 |

|

| |||||||

| Metabolic syndrome | 1199 (42.9) | 885 (46.9) | 0.01 | 1214 (43.4) | 916 (48.6) | <.001 | 0.55 |

|

| |||||||

| Statin use | 816 (29.2) | 1167 (61.9) | <.001 | 873 (31.2) | 1207 (64.1) | <.001 | 0.99 |

|

| |||||||

| Aspirin use | 1336 (47.8) | 1150 (61.0) | <.001 | 1312 (46.9) | 1116 (59.3) | <.001 | 0.70 |

|

| |||||||

| Mean FRS, % | 24.8±12.6 | 24.8±12.6 | 0.96 | 24.7±12.3 | 24.9±12.8 | 0.54 | 0.69 |

|

| |||||||

| No. of comorbidities, median [IQR] | 3.0 [2.0,5.0] | 6.0 [4.0,8.0] | <.001 | 3.0 [2.0,5.0] | 6.0 [4.0,8.0] | <.001 | 0.41 |

|

| |||||||

| No. of medications, median [IQR] | 3.0 [2.0,4.0] | 6.0 [5.0,8.0] | <.001 | 3.0 [2.0,4.0] | 6.0 [5.0,8.0] | <.001 | 1.00 |

|

| |||||||

| Atrial Fibrillation/Flutter | 150 (5.4) | 240 (12.8) | <.001 | 155 (5.6) | 209 (11.1) | <.001 | 0.23 |

|

| |||||||

| Myocardial Infarction | 120 (4.3) | 218 (11.6) | <.001 | 127 (4.5) | 201 (10.7) | <.001 | 0.38 |

|

| |||||||

| Heart Failure | 44 (1.6) | 122 (6.5) | <.001 | 45 (1.6) | 115 (6.1) | <.001 | 0.75 |

|

| |||||||

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 107 (3.8) | 143 (7.6) | <.001 | 101 (3.6) | 152 (8.1) | <.001 | 0.49 |

CVD=cardiovascular disease; eGFR=estimated glomerular filtration rate; FRS=Framingham Risk Score; HDL=high-density lipoprotein; IQR=interquartile range; SD=standard deviation

All values are no.(%) or means±SD unless noted otherwise

P-value for treatment randomization×medication burden status

Association of baseline medication burden and SBP, CVD events, SAEs, medication adherence, and treatment satisfaction

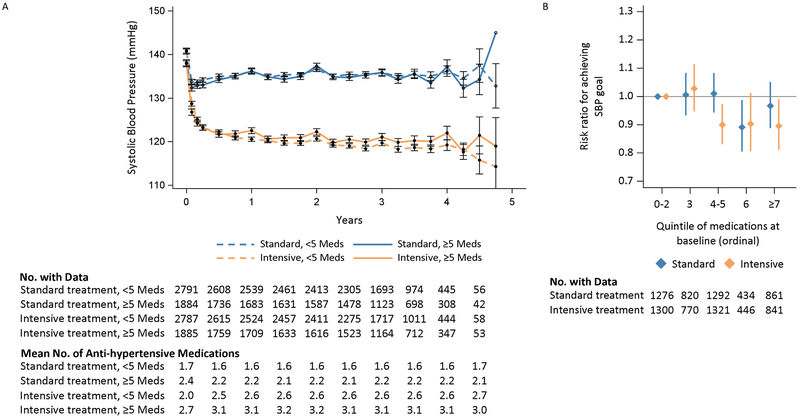

In the intensive treatment group at 12 months post-randomization, participants with high versus low baseline medication burden had a clinically small but statistically higher mean SBP level (122.5±14.3 mmHg versus 120.6±13.1 mmHg, P<0.001), experienced a smaller change in SBP from baseline (−15.3±18.2 mmHg versus −20.1±18.6 mmHg, P<0.001), and were less likely to achieve the assigned SBP goal (51.8% versus 58.3%, RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.85-0.97; Table 2). However, in the standard treatment group at 12 months, no statistically significant differences were observed between the high and low medication burden groups on achieved SBP level (136.2±14.8 mmHg versus 136.2±12.8 mmHg, P=0.63), change in SBP from baseline (−2.3±19.2 mmHg versus −4.5±17.7 mmHg, P=0.63), or likelihood of achieving the assigned SBP goal (63.6% versus 64.8%, RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.93-1.03). The Pinteraction between randomized treatment group and medication burden group were <0.001 for each of the three SBP metrics. Of 1,469 participants with available SBP data at 48 months post-randomization, the association between medication burden and SBP metrics was similar to that which was observed at 12 months for both randomization groups, although not statistically significant (Table S2). SBP differences between medication burden groups observed in the intensive treatment group were persistent throughout the trial (Figure 2, Panel A). Further, in the intensive treatment group, those with high medication burden were able to achieve lower SBP than those with high medication burden in the standard group throughout the trial. Differences in the likelihood of achieving the assigned SBP goal between the treatment groups were observed at 4-5 total baseline medications when medication burden was categorized by quintile (Figure 2, Panel B; Figure S4).

Table 2:

Blood Pressure and Clinical Outcomes by Treatment Group and Number of Baseline Medications

| Outcomes | Intensive treatment |

Standard treatment |

P interaction * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of baseline medications |

P-value or RR/HR (95% CI) | No. of baseline medications |

P-value or RR/HR (95% CI) | ||||

| < 5 | ≥ 5 | < 5 | ≥ 5 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Participants with SBP value at 12 months | (N=2,368) | (N=1,611) | (N=2,353) | (N=1,575) | |||

| SBP, mmHg | 120.6±13.1 | 122.5±14.3 | <0.001 | 136.2±12.8 | 136.2±14.8 | 0.63 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| SBP change, mmHg | −20.1±18.6 | −15.3±18.2 | <0.001 | −4.5±17.7 | −2.3±19.2 | 0.63 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||||

| Below randomization goal | 1381 (58.3) | 835 (51.8) | 0.91 (0.85-0.97) | 1524 (64.8) | 1001 (63.6) | 0.98 (0.93-1.03) | <0.001 |

| All Participants | (N=2,630) | (N=1,781) | (N=2,609) | (N=1,770) | |||

|

| |||||||

| CVD Events† | 98 (3.8) | 136 (7.7) | 1.32 (0.98-1.78) | 138 (5.4) | 170 (9.7) | 1.47 (1.13-1.92) | 0.53 |

|

| |||||||

| Any SAE‡ | 831 (31.9) | 872 (49.3) | 1.32 (1.18-1.47) | 786 (30.5) | 853 (48.4) | 1.35 (1.21-1.51) | 0.59 |

All values are no. (%) or means ± SD unless noted otherwise

CI=confidence interval, CVD=cardiovascular disease, HR=hazard ratio, RR=risk ratio, SAE=serious adverse event, SBP=systolic blood pressure, SD=standard deviation

P-value for treatment randomization×medication burden status

Composite of myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, heart failure, or death from cardiovascular causes

Figure 2: SBP and risk ratios for achieving SBP control by medication burden and treatment group.

Panel A: Mean SBP

Panel B: Adjusted risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals for achieving SBP goal at 12 months by quintile of medication burden

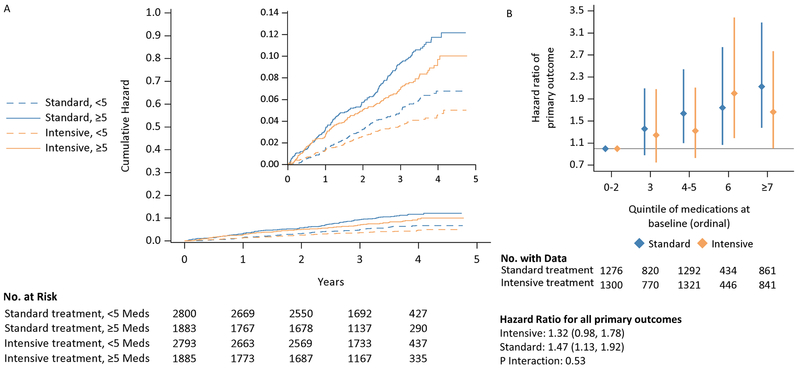

Participants with high versus low baseline medication burden were more likely to experience a composite CVD event outcome (HR 1.39, 95% CI 1.14-1.70; Figure 3, Panel A; Table 2/Table S3 for stratified analysis) and any SAE (HR 1.34, 95% CI 1.24-1.45; Table 2/Table S4 for stratified anlysis). The incidence of CVD events was progressively higher at higher levels of baseline medication burden (Figure 3, Panel B; Figure S4). These associations were similar regardless of treatment group (all Pinteraction>0.5). When stratified by treatment group, the association between high medication burden and increased risk of experiencing a CVD event (intensive: HR 1.32 [95% CI 0.98-1.78], standard: HR 1.47 [95% CI 1.13-1.92], Pinteraction=0.53) and SAE (intensive: HR 1.32 [95%CI 1.18-1.47], standard: HR 1.35 [95%CI 1.21-1.51]; Pinteraction=0.59) remained. These findings were not driven by increased associations with individual components of each composite measure.

Figure 3: Cumulative hazard plot and hazard ratios for CVD events outcome by medication burden and treatment group.

Panel A: Cumulative hazards for CVD event

Panel B: Adjusted risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals for experiencing CVD events by quintile of medication burden

At 12 months post-randomization, more participants in the standard treatment group with high medication burden reported “high” medication adherence (score of 8 on MMAS-8) compared to those with low medication burden (P<0.001); this association was not observed in the intensive treatment group (Pinteraction<0.001; Table S5). In both treatment groups, no significant differences were observed between high and low medication burden groups on MMAS-8 scores at 48 months or on TSQM responses at 12 and 48 months post-randomization (all Pinteraction>0.05, Tables S6–S8).

Effect modification of intensive SBP treatment by baseline medication burden

The beneficial effects of intensive versus standard SBP treatment on CVD events (i.e., reduced with intensive treatment group) and SAEs (i.e., no difference between treatment groups) were similar among those with and without high baseline medication burden (Table S9; all Pinteraction>0.5).

Sensitivity analyses

A detailed description of the results of all sensitivity analyses is provided in the Supplementary Results. Overall, the results of all sensitivity analyses were qualitatively similar to the main analysis (Figures S5–S7 and Tables S10–S16).

DISCUSSION

In this post-hoc analysis of SPRINT, high medication burden at baseline was significantly associated with a lower likelihood of achieving the intensive, but not the standard, SBP target at 12-months of follow-up. Within the intensive treatment group, participants with high versus low prescription medication burden had an approximately 10% lower likelihood of achieving an SBP of <120 mmHg at 12 months; high burden participants also had a higher mean SBP and a smaller change in SBP from baseline. In both treatment groups, high medication burden was associated with increased likelihood of experiencing a CVD event or an SAE. However, SAE rates were similar between treatment groups, and baseline medication burden did not impact the beneficial reduction in CVD events and mortality observed in the intensive treatment group. There were minimal differences in patient-reported adherence and treatment satisfaction between participants with high and low medication burden in both groups.

In the context of an aging population with increasing multi-morbidity, high medication burden prevalence is expected to rise. Up to 50% of patients aged 65 or older take five or more medications.24–28 Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) demonstrate an increasing prevalence of high medication burden over time in the entire population, from 8.2% in 1999-2000 to 15% in 2011-2012.26 Consistent with the current analysis, high medication burden has been associated with increased risks of experiencing an adverse drug event, drug-drug interactions, impaired balance and falls, frailty and disability, cognitive decline, hip fracture, delirium, hospital admission, and mortality.5,6,29–38 As comorbidity burden increases, clinicians are challenged with choosing medications that are most appropriate. While our analysis included adjustment for number of comorbidities, specific comorbidities, and age, we could not distinguish between inappropriate and appropriate medications in this study, and this remains an area that requires more research.

Within the intensive treatment group, we observed a statistically significant difference in 12-month SBP of 1.9 mmHg between the between the high and low medication burden groups. Although small, differences of such magnitude have the potential to have vast population health impacts. For example, data extrapolated from the INTERSALT study suggest that by lowering population-wide average SBP by 2.2 mmHg, risk for coronary death and stroke death would decrease by 4% and 6%, respectively.39 Moreover, pooled projections from clinical trials estimate that for every 5 mmHg reduction in SBP, risk for experiencing the composite cardiovascular endpoint decreases by 13%.40

Because there is no universal definition of high medication burden, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. Qualitatively, results were similar when including over-the-counter medications in the definition of medication burden and stratifying by the number of comorbidities at baseline, but the association with SBP control was not statistically significant when excluding antihypertensive medications from the definition. Furthermore, when categorizing medication burden into ordinal categories, ≥4 and ≥6 total medications was the threshold at which SBP control begins to diminish in the intensive and standard treatment groups, respectively (Figure 2, Panel B and Figure S4).

Similar to previous analyses on patient-reported outcomes in SPRINT, medication burden was not associated with clinically significant differences in medication adherence or treatment satisfaction at 12 or 48 months.8 This could be due to the measurement of these outcomes at 12 and 48 months, which largely ignore the effects of therapy intensification that occurred in the early phases of the trial (i.e., visits at 3, 6, and 9 months). Additionally, several patient- and provider-specific factors influence medication selection, adherence and treatment satisfaction, which complicate the achievement of clinical outcomes. These factors provide a complex clinical picture for managing hypertension and include cultural preferences, health literacy level, cost or financial burdens, medication allergies/interolerances or previous experiences with antihypertensives, the patient-provider fiducial relationship, potential for SAEs, and physician medication preferences, among others.41–43 These factors could not be accounted for in our analyses; further research is needed on how to optimize these factors to improve hypertension treatment and outcomes.

There are several study limitations worth noting. Although our results were consistent across sensitivity analyses and we included an extensive list of covariates in our adjusted models, there is an inherent risk of confounding as participants with higher baseline medication burden are also more likely to be the highest risk participants with more comorbidities. We did not adjust our results for multiple comparisons, increasing the type I error risk. Low participant numbers at long-term follow-up (i.e., 48 and 60 months post-randomization) limited our ability to determine long-term associations with medication burden because the trial was stopped early (median follow-up of 3.2 years) due to overwhelming benefit of intensive treatment. For this reason, we did not re-classify participants’ medication burden status beyond the baseline visit, although this may be of interest for future analyses. There is potential for misclassification of baseline medication burden status, particularly due to inconsistent collection or patient reporting of over-the-counter products, herbal supplements, and non-oral medications. Medication data collection within clinical research is time-consuming and arduous, and standardization solutions are needed.44,45 We were not able to detect and properly account for single-pill combination medications, which may have confounded the adherence analyses and led to the observed null association; thus, our analysis should be interpreted as investigating associations with medication burden rather than those of daily pill burden. Furthermore, we could not distinguish medications intended for short-term use (e.g., antibiotics) or account for the use of medications which may increase BP (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), which may have affected our results. Finally, differences in medication burden across race/ethnicity, sex, and comorbidity strata were not performed here due to small sample sizes but should be explored in future analyses.

PERSPECTIVES

In SPRINT, high medication burden was common and associated with a lower probability of achieving intensive SBP control. Medication burden was not associated with patient-reported medication adherence or treatment satisfaction. Importantly, the beneficial effects of intensive SBP control for reducing CVD events observed in the primary analysis persist irrespective of medication burden without a differential association with SAEs. Nonetheless, high medication burden was associated with increased risks of CVD events and SAEs irrespective of treatment group. Whether this reflects medication polytoxicities, patient behavior, drug-drug interactions or an inability to statistically control for medication use as a marker of sicker patients with multiple comorbidities, or a combination of these, is unresolved and deserving of further study.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance:

What Is New?

High medication burden (five or more prescription medications) was common and associated with increased risk of CVD events and SAEs in both treatment groups of a randomized clinical trial.

High medication burden was significantly associated with a higher SBP at 12 months and reduced likelihood of achieving an intensive SBP goal (<120 mmHg).

The beneficial effects of intensive SBP control (i.e., reduced CVD events) persisted irrespective of medication burden status.

What Is Relevant?

Adults with hypertension often take non-antihypertensive and antihypertensive medications to control comorbidities, thereby increasing risks associated with high medication burden (i.e., reduced medication adherence and increased serious adverse events).

Acknowledgments:

Drs. Adam P. Bress and Jordan B. King had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Co-authors Jennifer Herrick and Dr. Bress conducted and are responsible for the data analysis.

Sources of Funding:

This work was supported by R01HL139837 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD. Dr. Bress is supported by K01HL133468 and R01HL139837 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD. Dr. Moran is supported by R01HL130500-01A1 and R01HL139837 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD. Dr. Kronish is supported by UL1-TR001873 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Additional support was provided by the University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistics Center, with funding in part from the Public Health Services research grant numbers UL1-RR025764 and C06-RR11234 from the National Center for Research Resources.

Additional support was provided by K24HL125704 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NHLBI or the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of SPRINT for their valuable contributions.

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial is funded with Federal funds from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), including the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), the National Institute on Aging (NIA), and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), under Contract Numbers HHSN268200900040C, HHSN268200900046C, HHSN268200900047C, HHSN268200900048C, HHSN268200900049C, and Inter-Agency Agreement Number A-HL-13-002-001. It was also supported in part with resources and use of facilities through the Department of Veterans Affairs. The SPRINT investigators acknowledge the contribution of study medications (azilsartan and azilsartan combined with chlorthalidone) from Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. All components of the SPRINT study protocol were designed and implemented by the investigators. The investigative team collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. All aspects of manuscript writing and revision were carried out by the coauthors. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, or the United States Government. For a full list of contributors to SPRINT, please see the supplementary acknowledgement list: https://www.sprinttrial.org/public/dspScience.cfm

We also acknowledge the support from the following CTSAs funded by NCATS: CWRU: UL1TR000439, OSU: UL1RR025755, U Penn: UL1RR024134& UL1TR000003, Boston: UL1RR025771, Stanford: UL1TR000093, Tufts: UL1RR025752, UL1TR000073 & UL1TR001064, University of Illinois: UL1TR000050, University of Pittsburgh: UL1TR000005, UT Southwestern: 9U54TR000017-06, University of Utah: UL1TR000105-05, Vanderbilt University: UL1 TR000445, George Washington University: UL1TR000075, University of CA, Davis: UL1 TR000002, University of Florida: UL1 TR000064, University of Michigan: UL1TR000433, Tulane University: P30GM103337 COBRE Award NIGMS.

Footnotes

Registration: URL –-https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01206062. Unique Identifier: NCT01206062

Disclosures:

Dr. Morisky is the developer/owner of the copyrighted and trademarked protected Morisky Medication Adherence Scale and sells MMAS licenses and consulting services through MMAS Research LLC, 14725 NE 20th St., Bellevue, Washington 98007. Use of the ©MMAS is protected by the US and International copyright laws. Permission for use is required. A license agreement is available from Donald E. Morisky, MMAS Research (MORISKY), 294 Lindura Ct. 89138-4632, USA; dmorisky@gmail.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whelton PK. The Elusiveness of Population-Wide High Blood Pressure Control. Annual Reviews Public Health. 2015;36:109–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, Caughey GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatrics. 2017;17(1):230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hasler S, Senn O, Rosemann T, Neuner-Jehle S. Effect of a patient-centered drug review on polypharmacy in primary care patients: study protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2015;16:380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maher RL Jr., Hanlon JT, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 2014;13(1):57–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Blyth FM, Naganathan V, Waite L, Seibel MJ, Mclachlan AJ, Cumming RG, Handelsman DJ, Le Couteur DG. Polypharmacy cutoff and outcomes: five or more medicines were used to identify community-dwelling older men at risk of different adverse outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2012;65:989–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poudel A, Peel NM, Nissen LM, Mitchell CA, Gray LC, Hubbard RE. Adverse Outcomes in Relation to Polypharmacy in Robust and Frail Older Hospital Patients. JAMDA. 2016;17(8):e9–767.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright J Jr., Williamson J, Whelton P, Snyder J, Sink K, Roccoo M, Reboussin D, Mahboob R, Oparil S, Lewis C, Kimmel P, Johnson K, Goff D Jr., Fine L, Cutler J, et al. A Randomized Trial of Intensive versus Standard Blood-Pressure Control. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373:2103–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berlowitz DR, Foy CG, Kazis LE, Bolin LP, Conroy MB, Fitzpatrick P, Gure TR, Kimmel PL, Kirchner K, Morisky DE, Newman J, Olney C, Oparil S, Pajewski NM, Powell J, et al. Effect of Intensive Blood-Pressure Treatment on Patient-Reported Outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(8):733–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ambrosius WT, Sink KM, Foy CG, Berlowitz DR, Cheung AK, Cushman WC, Fine LJ, Goff DC, Johnson KC, Killeen AA, Lewis CE, Oparil S, Reboussin DM, Rocco M V, Snyder JK, et al. The design and rationale of a multicenter clinical trial comparing two strategies for control of systolic blood pressure: the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT). Clinical Trials. 2014;11(5):532–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D, Group M of D in RDS. A More Accurate Method to Estimate Glomerular Filtration Rate from Serum Creatinine: A New Prediction Equation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1999;130(6):461–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General Cardiovascular Risk Profile for Use in Primary Care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) protocol version 5.0. 2015.

- 13.Monégat M, Sermet C, Perronnin M, Rococo E. Polypharmacy: definitions, measurement and stakes involved. Review of the literature and measurement tests. 2014. http://www.irdes.fr/english/issues-in-health-economics/204-polypharmacy-definitions-measurement-and-stakes-involved.pdf. Accessed December 12, 2017.

- 14.Mortazavi SS, Shati M, Keshtkar A, Malakouti SK, Bazargan M, Assari S. Defining polypharmacy in the elderly: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e010989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox E, Martin BC, Van Staa T, Garbe E, Siebert U, Johnson ML. Good Research Practices for Comparative Effectiveness Research: Approaches to Mitigate Bias and Confounding in the Design of Nonrandomized Studies of Treatment Effects Using Secondary Data Sources: The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research Good Research Practices for Retrospective Database Analysis Task Force Report—Part II. Value in Health. 2009;12(8):1053–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. Journal of Clinical Hypertension (Greenwich). 2008;10(5):348–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 17.Muntner P, Joyce C, Holt E, He J, Morisky D, Webber LS, Krousel-Wood M. Defining the Minimal Detectable Change in Scores on the Eight-Item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2011;45:569–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krousel-Wood M, Islam T, Webber LS, Re RN, Morisky DE, Muntner P. New medication adherence scale versus pharmacy fill rates in hypertensive seniors. American Journal of Managed Care. 2009;15(1):59–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkinson MJ, Sinha A, Hass SL, Colman SS, Kumar RN, Brod M, Rowland CR. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2004;2:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson KC, Whelton PK, Cushman WC, Cutler JA, Evans GW, Snyder JK, Ambrosius WT, Beddhu S, Cheung AK, Fine LJ, Lewis CE, Rahman M, Reboussin DM, Rocco M V, Oparil S, et al. Blood Pressure Measurement in SPRINT (Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial) SPRINT Trial. Hypertension. 2018;71:848–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jorgensen T, Johansson S, Kennerfalk A, Wallander M-A, Svardsudd K. Prescription drug use, diagnoses, and healthcare utilization among the elderly. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2001;35:1004–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grimmsmann T, Himmel W. Polypharmacy in primary care practices: an analysis using a large health insurance database. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2009;18:1206–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCracken R, McCormack J, McGregor MJ, Wong ST, Garrison S. Associations between polypharmacy and treatment intensity for hypertension and diabetes: a cross-sectional study of nursing home patients in British Columbia, Canada. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e017430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qato DM, Alexander GC, Conti RM, Johnson M, Schumm P, Lindau ST. Use of prescription and over-the-counter medications and dietary supplements among older adults in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(24):2867–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qato DM, Wilder J, Schumm LP, Gillet V, Alexander GC. Changes in Prescription and Over-the-Counter Medication and Dietary Supplement Use Among Older Adults in the United States, 2005 vs 2011. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016;176(4):473–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in Prescription Drug Use among Adults in the United States from 1999–2012. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1818–1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elmståhl S, Linder H. Polypharmacy and Inappropriate Drug Use among Older People: A Systematic Review. Healthy Aging & Clinical Care in the Elderly. 2013;5:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hajjar ER, Cafiero AC, Hanlon JT. Polypharmacy in Elderly Patients. The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. 2007;5(4):345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olsson IN, Runnamo R, Engfeldt P. Medication quality and quality of life in the elderly, a cohort study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2011;9:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muhlack DC, Hoppe K, Weberpals J, Brenner H, Schöttker B. The Association of Potentially Inappropriate Medication at Older Age With Cardiovascular Events and Overall Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. JAMDA. 2017;18:211–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bourgeois FT, Shannon MW, Valim C, Mandl KD. Adverse drug events in the outpatient setting: an 11-year national analysis. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2010;19(9):901–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agostini JV., Han L, Tinetti ME. The relationship between number of medications and weight loss or impaired balance in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(10):1719–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai S-W, Liao K-F, Liao C-C, Muo C-H, Liu C-S, Sung F-C. Polypharmacy Correlates With Increased Risk for Hip Fracture in the Elderly. Medicine. 2010;89(5):295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin NJ, Stones MJ, Young JE, Bédard M. Development of delirium: a prospective cohort study in a community hospital. International Psychogeriatrics. 2000;12(1):117–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peron EP, Gray SL, Hanlon JT. Medication use and functional status decline in older adults: a narrative review. The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. 2011;9(6):378–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koyama A, Steinman M, Ensrud K, Hillier TA, Yaffe K. Long-term cognitive and functional effects of potentially inappropriate medications in older women. Journal of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2014;69(4):423–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Espino DV, Bazaldua OV, Palmer RF, Mouton CP, Parchman ML, Miles TP, Markides K. Suboptimal Medication Use and Mortality in an Older Adult Community-Based Cohort: Results From the Hispanic EPESE Study. Journal of Gerontology. 2006;61A(2):170–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pérez T, Moriarty F, Wallace E, Mcdowell R, Redmond P, Fahey T. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people in primary care and its association with hospital admission: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2018;363:k4524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stamler J, Rose G, Stamler R, Elliott P, Dyer A, Marmot M. INTERSALT Study Findings: Public Health and Medical Care Implications. Hypertension. 1989;14(5):570–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verdecchia P, Gentile G, Angeli F, Mazzotta G, Mancia G, Reboldi G. Influence of blood pressure reduction on composite cardiovascular endpoints in clinical trials. Journal of Hypertension. 2010;28(7):1356–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krousel-Wood M, Thomas S, Muntner P, Morisky D. Medication adherence: A key factor in achieving blood pressure control and good clinical outcomes in hypertensive patients. Current Opinion in Cardiology. 2004;19(4):357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Choi HY, Oh IJ, Lee JA, Lim J, Kim YS, Jeon T-H, Cheong Y-S, Kim D-H, Kim M-C, Lee SY. Factors Affecting Adherence to Antihypertensive Medication. Korean Journal of Family Medicine. 2018;39(325–332):325–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oliveria SA, Lapuerta P, McCarthy BD, L’Italien GJ, Berlowitz DR, Asch SM. Physician-Related Barriers to the Effective Management of Uncontrolled Hypertension. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2002;162:413–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richesson RL, Smith SB, Malloy J, Krischer JP. Achieving standardized medication data in clinical research studies: two approaches and applications for implementing RxNorm. Journal of Medical Systems. 2010;34(4):651–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saczynski JS, McManus DD, Goldberg RJ. Commonly used data-collection approaches in clinical research. The American Journal of Medicine. 2013;126(11):946–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.