Abstract

We report the luminescence and spectral properties of a phospholipid analogue containing a long-lifetime luminescent rhenium metal–ligand complex (MLC) covalently linked to the amino group of phosphatidyl ethanolamine. When incorporated into synthetic membranes, this lipid probe displays intensity decay times near 3 μs. Importantly, the probe displays highly polarized emission with a maximal fundamental anisotropy of 0.33. This probe is expected to have numerous applications for studies of microsecond diffusion and dynamics of membranes.

Keywords: Long-lifetime lipid, Rhenium metal–ligand complex, Membrane dynamics

1. Introduction

Cell membranes are predominantly composed of phospholipids, which are spectroscopically silent in the ultraviolet and visible regions of the spectrum. Extrinsic fluorophores embedded in membranes or attached to the phospholipids often serve as important reporter molecules to study the structure and dynamics of lipid membranes (Dewey et al., 1991; Stubbs et al., 1992; Slavik et al., 1994). The properties of membranes have been studied using a variety of fluorescence techniques, such as lifetime, anisotropy, energy transfer, solvent effects, and quenching. However, the vast majority of membrane probes display excited state lifetimes of only 1–10 ns, which restricts the time of observation and restricts the information obtained to the ns timescale. The few organic fluorophores with longer lifetimes include pyrene (Hresko et al., 19860, which displays a lifetime of ~100 ns but low anisotropy, and coronene, which shows a lifetime of 200 ns and complex anisotropy decays in membrane (Davenport et al., 1988). Phosphorescence has been used to circumvent the limitations of using short lifetime probes (Gonzalez-Rodriguez et al., 1994; Voss et al., 1995). However measurements of phosphorescence require complete exclusion of oxygen. Also, time-zero anisotropies of phosphorescence are often low. Clearly, there is the need for additional long-lifetime membrane probes.

In the present communication we continue the development of lipid probes containing long-lifetime metal–ligand complexes. As a class of luminescent probes, the transition metal–ligand complexes are unique in that their spectral properties, such as excited state lifetime, maximum emission wavelength, fundamental anisotropy, and quantum efficiency, can be varied by changing the coordinating ligands. In the previous reports we have shown that ruthenium metal–ligand lipid probes display intensity decay times of several hundred nanoseconds, and that such long decay times allow measurements of the overall rotational correlation time as long as several microseconds, which were assigned to overall rotation of the lipid vesicles (Li et al., 1997a,b). To further expand the usefulness of metal–ligand complexes in studies of lipid membranes, we synthesized a phospholipid analogue (Re-PE) of [Re(4,7-Me2phen)(CO)3(4-COOHPy)] (PF6), where 4,7-Me2phen is 4,7-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline, 4-COOHPy is isonicotinic acid, and PE stands for dipalmitoyl-l-α-phosphatidyl ethanolamine (Scheme I). This complex displays intensity decay times of several microseconds (Guo et al., 1997a), displays highly polarized emission, and has already been used in polarization immunoassays (Guo et al., 1997b). In the present paper, we extend our previous studies with the probe (Guo et al., 1997a) to include measurement of the overall rotational motion of lipid vesicles and microsecond dynamics of cell membranes.

Scheme I.

Molecular structure of the phospholipid analogue of [Re(4,7-Me2phen)(CO)3(4-COOHPy)]+(Re-PE).0

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Synthesis of [Re(4,7-Me2phen)(CO)3 (4-COOHPy)](PF6)

All reactions were performed in the dark under an atmosphere of argon. Re(4,7-Me2phen) (CO)3Cl, [Re(4,7-Me2phen)(CO)3(CH3CN)](PF6), and [Re(4,7-Me2phen)(CO)3(4-COOHPy)](PF6) were prepared by literature procedures (Sacksteder et al., 1990; Worl et al., 1991; Guo et al., 1997a,b). The final carboxylic acid product was obtained using the pure, isolated acetonitrile intermediate instead of the one pot synthesis used previously (Guo et al., 1997a) and further purified by chromatography on SiO2 using CHCl3/MeOH (2.5/1, v/v) as the eluent.

2.2. Synthesis of Re-PE

The activated rhenium complex was synthesized by formation of the NHS-ester of the carboxyl groups. 200 mg of [Re(4,7-Me2phen)(CO)3(4-COOHPy)](PF6) and 35 mg of N-hydroxysuccinimide were dissolved in 0.5 ml of acetonitrile at room temperature. N,N′-Dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (60 mg) was then added to the above solution. The mixture was sealed and stirred for 10 h. The formed precipitate was removed by filtration through a syringe filter (Nylon Acrodish, 0.45 μm pore size). The filtrate containing the activated rhenium complex was directly added to the mixture of dipalmitoyl-l-α-phosphatidyl ethanolamine (120 mg in 2.0 ml of CHCl3) and 1.2 ml triethylamine under an atmosphere of argon. The reaction mixture was stirred overnight in the dark. The solvents were then removed under vacuum and the product was redissolved in 2.0 ml of CHCl3/MeOH (2/1, v/v). The pure Re-PE was obtained through purification by TLC on K6F SiO2 plates using CHCl3/MeOH/NH4OH (65/25/4, v/v/v) as the eluent. The Rf value of Re-PE is 0.64, relative to that of PE (0.55), and the final product yield is near 10%. The product recovered from Rf=0.64 band was the only luminescent band observed on the thin layer plates.

2.3. Instrumentation

UV-Vis spectra were measured on a HP 8453 diode array spectrophotometer with ±1 nm resolution. Steady-state emission spectra were obtained on a SLM AB2 fluorimeter under magic angle polarization conditions. The frequency-domain instrumentation (ISS) was used for measurements of the fluorescence intensity and anisotropy decays. The excitation source was an argon ion (10 W, Spectra Physics 2060) pumped, mode-locked Ti:Sapphire (Ti:S) laser (Tsunami, Spectra Physics) with a repetition rate of 80 MHz at 800 nm (90 fs fwhm) with an average power of 1.1 W. This laser is equipped with the loc-to-clock option in which a PZT mounted mirror maintains the 80 MHz repetition rate. This signal also provides the frequency standard for synchronization of the laser with the frequency domain (FD) instrumentation. The 80 MHz output of the Ti:S laser was pulse picked with an external cavity acousto-optic pulse selector to reduce the repetition rate to 40 or 80 kHz (Spectra Physics, Model 3980). The procedure of pulse picking lowers the average power of the laser output more than 1000-fold (<1 mW). The selected pulses were frequency doubled with an Inrad model 5–050 ultrafast doubler/tripler to yield ~100 fs pulses at 400 nm. These 400 nm pulses were used to excite the samples after adjusting the polarization to vertical with a rotator (Special Optics). Emission was collected at 90° in an ISS Koala chamber with an R-928 PMT equipped with a 500 nm cutoff filter (Andover 500FH90–50S) in the emission path. The ISS frequency-domain fluorimeter was equipped with a Marconi Instruments 2022D frequency synthesizer output into an ENI 3W linear RF amplifier (150 kHz–300 MHz) for modulation of the detection system. Data was collected at integer multiples of the base laser frequency (40 or 80 kHz) using a 40 Hz cross-correlation frequency.

The frequency-domain luminescence intensity and anisotropy decays were analyzed by a nonlinear least squares procedure described previously (Lakowicz et al., 1984, 1991). Briefly, the intensity decays were described by

| (1) |

where αi and τi are the preexponential weighting factors and the excited state lifetimes, respectively. The anisotropy decays were fit to

| (2) |

where gir0 is the amplitude of the anisotropy decaying with the rotational correlation time θi with the restriction that Σgi=1.0, and r0 is the fundamental anisotropy in the absence of the rotational diffusion. If the measurements recover the entire anisotropy decay then r0 is also the time-zero anisotropy.

2.4. Preparation of phospholipid vesicles

Aliquots of Re-PE and DPPG in chloroform were taken from stock solutions, and kept in a water bath at a constant temperature of 55°C while the solvent was removed by a stream of argon. Vesicles were prepared by sonication in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.2, at final lipid concentration of 1.5 mg/ml. The molar ratio of Re-PE to DPPG was fixed at 1/25 in this study. Since the rhenium metal–ligand complex is located on the amino group of PE, the Re-PE probe can probably be incorporated into the membranes without substantial perturbation of the lipid side chains. Unless stated otherwise, all measurements were performed in a deaerated atmosphere.

3. Results

The chemical structure of Re-PE is given in Scheme I. The absorption and emission spectra of Re-PE in DPPG vesicles at 20°C are shown in the Fig. 1. The strong UV band at 280 nm and the broad shoulder absorbance above 300 nm are due to the ligand-centered transition and MLCT transition, respectively (Wallace et al., 1993). Emission of Re-PE is broad with the maximum peak at 535 nm, which has been assigned as MLCT-based luminescence (Wallace et al., 1993; Guo et al., 1997a). These two spectra display a large Stokes’ shift and the scattered light from membrane suspensions can be easily eliminated from the detected emission. A large Stokes’ shift is also useful because membranes can contain relatively large amounts of probe without loss of anisotropy due to homo-resonance energy transfer (Lakowicz, 1999).

Fig. 1.

Absorption and emission spectra of Re-PE in DPPG vesicles at 20°C. Also shown is the excitation anisotropy spectrum of the parent compound [Re(,4,7-Me2phen)(CO)3(4-COOHPy)]+ in glycerol/methanol at −60°C.

Frequency-domain intensity decays of Re-PE in lipid membranes are shown in Fig. 2. These decays are best fit to three exponential decay law and the recovered lifetimes are listed in Table 1. The mean lifetimes, calculated using [p116]=Σiαiτi2/Σi αiτi, are approximately unchanged for Re-PE in DPPG vesicles at 10 and 30°C, below the gel phase to fluid phase transition temperature at 41°C. However, the mean lifetime above 41°C is substantially shorter. The result is likely due to changes in the probe environment which occur during the phase transition of lipid vesicles. The fact that the intensity of Re-PE is influenced by the lipid is seen by noting the single exponential decay of 5.9 μs in deaerated chloroform (not shown).

Fig. 2.

Frequency-domain intensity decays of Re-PE incorporated in DPPG vesicles at various temperatures.

Table 1.

Frequency-domain intensity and anisotropy decays of Re-PE in DPPG vesicles at various temperatures

| T (°C) | Intensity decays | Anisotropy decays | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αi | τi (ns) | θi (ns) | r0gi | ||||

| 10 | 0.238 | 112.6 | 3791.1 | 30.3 | 0.298 | ||

| 0.406 | 1142.9 | 1269.8 | 0.032 | 1.4 (35.7)a | |||

| 1.8 (130.6)a | 0.356 | 4676.3 | |||||

| 30 | 0.441 | 185.0 | 3845.4 | 14.0 | 0.301 | ||

| 0.292 | 1096.0 | 1305.1 | 0.029 | 3.2 (31.2) | |||

| 2.4 (490.6) | 0.267 | 4772.0 | |||||

| 45 | 0.476 | 23.8 | 2340.0 | 10.3 | 0.315 | ||

| 0.189 | 353.7 | 2431.1 | 0.015 | 2.9 (14.0) | |||

| 1.5 (341.1) | 0.335 | 2727.7 | |||||

In parentheses are values for the best single exponential fits. For the least squares analysis we used an uncertainity of 0.4° in the phase angle and 0.01 in the modulation.

For use as an anisotropy probe to study the hydrodynamics of lipid membranes, the metal–ligand complex must display polarized emission. We examined the excitation anisotropy spectrum of the parent compound, [Re(4,7-Me2phen)(CO)3(4-COOHPy)](PF6), dissolved in glycerol/methanol (95/5, v/v) under vitrified condition (−60°C) to avoid rotational diffusion (Fig. 1). This complex shows a maximal anisotropy of 0.33, which is sufficient for measurement of the time-resolved anisotropies. The reason for using the parent compound to obtain the fundamental anisotropy, instead of Re-PE, is the poor solubility of Re-PE in glycerol/methanol. Also, we found in previous studies that the excitation anisotropy spectra were similar for the MLC probes as the free carboxylic acids or when covalently bound to the amino groups of proteins (Terpetschnig et al., 1995; Szmacinski et al., 1996). Therefore, we expect the anisotropy spectrum of the parent MLC to reflect that of the lipid conjugate. This hypothesis has been verified in measurements of the time-resolved anisotropy using ruthenium MLC lipid probes (Li et al., 1997b). In this case, the total anisotropy recovered in DPPG vesicles at low temperature(2°C) closely approaches to the fundamental anisotropy value.

The frequency-domain anisotropy decays of DPPG vesicles labeled with Re-PE at various temperatures are shown in Fig. 3. For measurement of the frequency-domain anisotropy of Re-PE in DPPG vesicles, the chosen excitation wavelength was 400 nm at which the fundamental anisotropy of Re-PE is near 0.33. Analysis of these data in terms of two rotational correlation times using Eq. (2) are summarized in Table 1. The total anisotropy was fixed to 0.33 during the analyses. The short rotational correlation time near 10–30 ns probably reflects the fast rotational motion of rhenium MLC by itself. The longer correlation time (≈ 1.3 μs) recovered is consistent with that expected for overall rotational diffusion of phospholipid vesicles with the diameter between 200 and 250 Å. According to the Stokes–Einstein equation, the rotational correlation time is given by θ=ηV/RT, where η is the viscosity of the medium and is equal to 1 cP, V is the volume of single lipid vesicle, and T=297 K. Vesicles with diameters of 200 and 250 Å are expected (Li et al., 1997b) to display correlation times of 1034 and 2020 ns, respectively, which are comparable to the recovered values. The amplitude of the long correlation time dropped by half as the temperature was increased from 10 to 45°C. However, the slow vesicular rotational persists even at 45°C, above the lipid phase transition temperature (41°C). Also, the correlation time recovered at 45°C is as long or longer than those found below the phase transition temperature, possibly resulting from the scattered data points and the low value of the fractional anisotropy contributed by this slow rotational motion which affect the accuracy of the analysis. However, it is also possible that the long correlation time has increased due to aggregation of the vesicles. Further studies are required to clarify this conjecture.

Fig. 3.

Frequency-domain anisotropy decays of DPPG vesicles labeled with Re-PE.

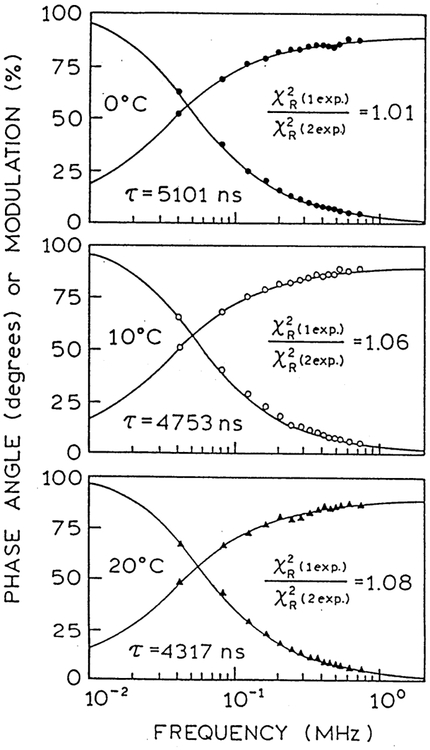

It is interesting to examine the time-dependent anisotropy decays reconstructed from the recovered parameters (Fig. 4). At temperatures above and below the phase transition temperature of the lipid the anisotropies show rapid decreases below 100 ns, followed by a much slower loss of the remaining anisotropy over several microseconds. For use as an anisotropy probe it is important to know if the complex anisotropy decay displayed by the MLC probe is due to its motions, and not due to some fundamental property of the probe. Hence we examined the intensity and anisotropy decay of the parent component Re(4,7-Me2phen)(CO)3(4-COOHPy) in glycerol. The intensity decays were found to be single exponential at all studied temperatures (Fig. 5 and Table 2). Importantly, the anisotropy decays displayed a single correlation time and a time-zero anisotropy near 0.32, with no evidence of a more rapid component. (Fig. 6). Hence the probe does not display any unusual anisotropy behavior, and can be reliably expected to report on microsecond molecular motions.

Fig. 4.

Reconstructed time-domain anisotropy, decays of DPPG vesicles labeled with Re-PE.

Fig. 5.

Frequency-domain intensity decay of Re(Me2-phen)(CO)3 (COOHPy) PF6 in glycerol.

Table 2.

Fluorescence intensity and anisotropy decay analyses of (Re(4,7-dimethyl-phen (CO)3 py-COOH)PF6 in glycerol at various temperatures

| T (°C) | τ (ns) | r0 | Θ (ns) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5101.0 | 2.4 | 1.01 | 0.316 | 1026.7 | 3.7 | 1.07 |

| 10 | 4752.6 | 2.3 | 1.06 | 0.316 | 356.5 | 2.3 | 1.04 |

| 20 | 4316.8 | 3.4 | 1.08 | 0.314 | 98.4 | 0.9 | 1.00 |

| Global fit | |||||||

| 0 | – | 0.316 | 1027.4 | 2.3 | 1.03 | ||

| 10 | – | 356.1 | |||||

| 20 | – | 97.6 |

Fig. 6.

Frequency-domain anisotropy decay of Re(Me2-phen)(CO)3 (COOHPy) PF6 in glycerol.

In order to obtain additional information on the overall hydrodynamics of membranes it would be valuable to decrease the amplitude of the faster motion. This could possibly be accomplished by attaching the rhenium complex to two lipid molecules, as has been done previously for a luminescent ruthenium complex (Li et al., 1997b). In summary, long lifetime rhenium-lipid complexes are promising new probes for the microsecond dynamics of membranes.

4. Discussion

The rhenium MLC–lipid conjugate described in this report is a result of the continuing effort in this laboratory to explore the usefulness of the metal–ligand complexes in biochemistry and biophysics (Terpetschnig et al., 1997; Szmacinski et al., 1996; Lakowicz et al., 1997; Malak et al., 1997; Castellano et al., 1998; Terpetschnig et al., 1998). The important point is that MLCs can display a variety of spectral properties. For example, by selection of the metal ion or ligand, one can increase the quantum efficiency to about 0.5 and extend the excited state lifetime to over 10 μs (Kober et al., 1985; Zipp et al., 1993). It is also possible to obtain probes with maximal emission from 500 to 800 nm, although generally with a reduced lifetime (Pankuch et al., 1980; Juris et al., 1988; Sacksteder et al., 1990). For the study of highly scattering membrane suspensions, long-lifetime MLCs are especially attractive because they allow off-gating detection to eliminate the prompt autofluorescence, display useful anisotropy, and they are highly stable and conjugatable.

Re-PE in this study shows highly polarized emission with the fundamental anisotropy of 0.33, which is much higher than those of ruthenium lipid conjugates in the previous report (Li et al., 1997b). The luminescence quantum yield of Re-PE is near 0.08, also higher than those in the previous study. Moreover, it displays mean lifetime of 3.8 μs, which in principle allows to measure rotational motions of membranes to nearly 12 μs, or about three times the mean decay time. Hence, this probe is suitable for studying hydrodynamics of cell membranes with diameters of several micrometers. This probe allowed measurement of the DPPG vesicles, which cannot be accomplished with ns decay time probes. To make use of the long luminescence lifetime, Re-PE has also been used to measure lateral diffusion coefficient in the lipid membranes by resonance energy transfer, which will be published elsewhere. All of these ascertain the feasibility of using long lifetime MLC probes to study the microsecond dynamics of membranes.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (GM-35154 and RR-08119) for the support of this research. FNC was supported by a NIH fellowship.

Abbreviations:

- FD

frequency-domain

- 4,7-Me2phen

4,7-dimethyl-1,10-phenanthroline

- MLCT

metal-to-ligand charge transfer

- 4-COOHPy

isonicotinic acid

- PE

dipalmitoyl-l-α-phosphatidyl ethanolamine

- Re-PE

PE with the covalently attached rhenium complex

- Ti:S

titanium sapphire

References

- Castellano FN, Dattelbaum D, Lakowicz JR, 1998. Long-lifetime Ru(II) complexes as labeling reagents for sulfhydryl groups. Anal. Biochem 255, 165–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport L, Knutson JR, Brand L, 1988. Time-resolved fluorescence anisotropy of membrane probes: Rotations gated by packing fluctuations. SPIE Proc. 909, 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey TG (Ed.), 1991. Biophysical and Biochemical Aspects of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Plenum, New York, p. 294. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Rodriguez J, Acun AU, Alvarez MV, Jovin TM, 1994. Rotational mobility of the fibrinogen receptor glycoprotein IIb/IIIa or integrin (IIb(3 in the plasma membrane of human platelets. Biochemistry 33, 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo XQ, Castellano FN, Li L, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, Sipior J, 1997a. A long-lived highly luminescent Re(I), metal–ligand complex as a biomolecular probe. Anal. Biochem 254, 179–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X-Q, Castellano FN, Li L, Lakowicz JR, 1997b. Use of a long-lifetime Re(I) complex in fluorescence polarization immunoassays of high-molecular-weight analytes. Anal. Chem 70 (3), 632–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hresko RC, Sugar P, Barenholz Y, Thompson TE, 1986. Lateral distribution of a pyrene-labeled phosphatidylcholine in phosphatidylcholine bilayers: Fluorescence phase and modulation study. Biochemistry 25, 3813–3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juris A, Balzani V, Barigelletti F, Campagna S, Belser P, Von Zelewsky A, 1988. Ru(II) polypyridine complexes: photophysics, photochemistry, electrochemistry, and chemiluminescence. Coord. Chem. Rev 84, 85–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kober EM, Marshall JL, Dressick WJ, Sullivan BP, Caspar JV, Meyer TJ, 1985. Synthetic control of the excited states. Nonchromophoric ligand variations in polypyridyl complexes of osmium(II). Inorg. Chem 24, 2755–2763. [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz JR, Gratton E, Laczko G, Cherek H, Limkeman M, 1984. Analysis of fluorescence decay kinetics from variable-frequency phase shift and modulation data. Biophys. J 46, 463–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz JR, Gryczynski I, 1991. Fluorescence in membranes In: Lakowicz JR (Ed.), Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Volume: 1 Techniques. Plenum, New York, pp. 293–335. [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz JR, Terpetschnig E, Murtaza Z, Szmacinski H, 1997. Development of long-lifetime metal–ligand probes for biophysics and cellular imaging. J. Fluoresc 7, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lakowicz JR, 1999. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 2nd ed Plenum Press, New York: (in press). [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, 1997a. Long-lifetime lipid probe containing a luminescent metal–ligand complex. Biospectroscopy 3, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, 1997b. Synthesis and luminescence spectral characterization of long-lifetime lipid metal–ligand probes. Anal. Biochem 244, 80–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malak H, Gryczynski I, Lakowicz JR, Meyer GJ, Castellano FN, 1997. Long-lifetime metal–ligand complexes as luminescent probes for DNA1–5. J. Fluorescence 7 (2), 107–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankuch BJ, Pankuch DE, Crosby GA, 1980. Charge-transfer excited states of osmium(II) complexes. 1. Assignment of the visible absorption bands. J. Phys. Chem 84, 2061–2067. [Google Scholar]

- Sacksteder L, Zipp AP, Brown EA, Streich J, Demas JN, DeGraff BA, 1990. Luminescence studies of pyridine α-diimine rhenium(I) tricarbonic complexes. Inorg. Chem 29, 4335–4340. [Google Scholar]

- Slavik J, (Ed.), 1994. Fluorescent Probes in Cellular and Molecular Biology. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs CD, Williams BW, 1992. Fluorescence in membranes In: Lakowicz JR (Ed.), Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy, Vol: 3 Biochemical Applications. Plenum, New York, pp. 231–271. [Google Scholar]

- Szmacinski H, Terpetschnig E, Lakowicz JR, 1996. Synthesis and evaluation of Ru-complexes as anisotropy probes for protein hydrodynamics and immunoassays of high-molecular-weight antigens. Biophys. Chem 62, 109–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpetschnig E, Dattelbaum JD, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, 1997. Synthesis and Spectral Characterization of a Thiol-Reactive Long-Lifetime Ru(II) Complex. Anal. Biochem 251, 241–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, Malak H, Lakowicz JR, 1995. Metal–ligand complexes as a new class of long-lived fluorophores for protein hydrodynamics. Biophys. J 68, 342–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpetschnig E, Szmacinski H, Lakowicz JR, 1998. Long-lifetime MLSs as probes In: Lakowicz JR (Ed.), Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Plenum, New York, pp. 294–321. [Google Scholar]

- Voss JC, Mahaney JE, Jones LR, Thomas DD, 1995. Molecular dynamics in mouse atrial tumor sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biophys. J 68, 1787–1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace L, Rillema DP, 1993. Photophysical properties of rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes containing alkyl- and aryl-substituted phenanthrolines as ligands. Inorg. Chem 32, 3836–3843. [Google Scholar]

- Worl LA, Duesing R, Chen P, DellaCiana L, Meyer TJ, 1991. Photophysical properties of polypyridyl carbonyl complexes of rhenium(I). J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. (150th Anniversary Celebration Issue), 849–858. [Google Scholar]

- Zipp AP, Sacksteder L, Streich J, Cook A, Demas JN, DeGraff BA, 1993. Luminescence of rhenium(I) complexes with highly sterically hindered (diimine ligands. Inorg. Chem 32, 5629–5632. [Google Scholar]