Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) represents an important and growing public health problem, chronically infecting an estimated 70 million people worldwide. This blood-borne pathogen is generating a new wave of infections in the United States, associated with increasing intravenous drug use over the last decade. In most cases, HCV establishes a chronic infection, sometimes causing cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Although a curative therapy exists, it is extremely expensive and provides no barrier to reinfection; therefore, a vaccine is urgently needed. The virion is asymmetric and heterogeneous with the buoyancy and protein content similar to low-density lipoparticles. Core protein is unstructured, and of the two envelope glycoproteins, E1 and E2, the function of E1 remains enigmatic. E2 is responsible for specifically binding host receptors CD81 and scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI). This review will focus on structural progress on HCV virion, core protein, envelope glycoproteins, and specific host receptors.

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) affects an estimated 70 million people globally, in a bimodal age distribution (Moore et al. 2019). Baby boomers had a higher exposure rate to HCV between the 1960s and the 1980s, mainly from blood transfusion prior to screening efforts (∼40%) or from intravenous drug use (30%) (Williams 1999). The fastest growing population, however, is among young adults who have a history of intravenous drug use. For people ages 20–39, new diagnoses tripled between 2005 and 2015 (Shiffman 2018). Direct-acting antiviral drugs (DAAs) now present a means for curing HCV infection, albeit an expensive one, costing between $26,500 and $94,500 depending on regimen. This cure now boasts a near-100% rate of effectiveness on all HCV genotypes tested, but it is limited in its impact on public health by cost. Once cured, a person has no barrier to reinfection, which is of particular concern in the context of addiction and intravenous drug use. Furthermore, a person cured of HCV might have a higher likelihood of developing hepatocellular carcinoma than if they were treated with interferon (Cardoso et al. 2016; Conti et al. 2016; Reig et al. 2016a); this is controversial because of sample size and cohort variability among studies (Reig et al. 2016b; Guarino et al. 2018). For these reasons, development of effective vaccine strategies remains the ultimate goal of HCV research.

An effective vaccine would elicit the production of antibodies that bind tightly and specifically to epitopes that are common to all genotypes of HCV and that efficiently neutralize the viral particle. Broadly neutralizing antibodies directly implicate the viral epitopes that, if correctly reconstituted in isolation, could form the basis of safe and effective vaccine candidates. For this reason, the structural characterization of the surface-accessible epitopes remains a subject of significant interest.

As a chronic infection, HCV maintains its reservoir in the liver as well as its transmissibility circulating in the bloodstream for decades. People living with these infections develop antibodies against HCV, but these are generally genotype- or subgenotype-specific and non-neutralizing. The former indicates that epitopes available for antibody binding are variable. The latter suggests that antibody binding to these epitopes does not interfere with the mechanics of viral infection. The mechanisms of how HCV tolerates these antibodies and evades immune clearance over the course of a human lifetime continues to be a mystery that warrants attention and may provide insight into indirect methods of controlling or limiting the impact of HCV infection.

HCV was initially defined by what it was not. Under the electron microscope, sera from viral hepatitis patients are distinguishable by the viral particles they contain, and identification affects patient prognosis as well as precautions against transmission. The regular, icosahedral shape of naked hepatitis A virus capsids appear in striking contrast to the circulating viral products of hepatitis B, where enveloped empty and full capsids of two different sizes appear among elongated particles of empty envelope material. Neither these hallmarks, nor any others common to viruses in circulation, were observed in sera from non-A/non-B hepatitis patients as HCV was called before it was positively identified (Holland and Alter 1981). Eventually, HCV was identified by serologic exclusion of both hepatitis A and hepatitis B and was eventually followed by positive immunological identification (Vitvitski et al. 1979; Holland and Alter 1981).

The low rate of HCV virus production (about seven virions per hepatocyte per day) that befits a chronic infection has also hindered the progress of research on the structure of HCV viral particles. In the whole-liver context, ∼1012 virions are made per day (Neumann et al. 1998), but tissue culture has a far lower capacity. Structural observations have either been made from systems designed to circumvent this limitation or inferred by homology to more amenable relatives whose fields have advanced more quickly than HCV research. HCV is a member of the Flaviviridae family, along with dengue, West Nile, yellow fever, and Zika viruses. HCV contains a 9.6-kbp (+)ssRNA genome, expressing a single polyprotein that is cleaved into its 10 mature components by host and viral encoded proteases. In HCV, core (C) protein is expressed first, followed by the envelope (E) protein(s), an ion channel (p7), and then the nonstructural (NS) proteins. As they are produced, virions traffic through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi, acquiring glycosylation to generate the mature particle for circulation in the bloodstream. Virions enter cells through an endosomal triggering event that launches the nucleocapsid into the host cytoplasm. Unlike other family members, HCV is not transmitted via arthropod and so has no need for a temperature-based switch, as was observed in dengue virus (Zhang et al. 2013). So, although several inferences can be made based on homology to better-studied systems, these models need to be tested for relevance in HCV.

HCV circulates in the bloodstream for blood-contact-based transmission; even minute quantities of blood have resulted in transmission (Hosoglu et al. 2003; Egro et al. 2017). HCV targets the liver by binding to receptors in the lipid metabolism pathway, including scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI), claudin-1, and occludin, and heavily remodels and utilizes the lipoparticle biosynthetic pathway in its life cycle. These mechanisms affect clinical presentation, particularly regarding liver steatosis and nonhepatic symptoms including atherosclerosis (Targher et al. 2007) and heart attack (Butt et al. 2017). The mechanisms by which this virus so efficiently targets the liver, evades immune response, and proceeds to chronic infection warrant careful consideration.

With only 10 proteins, HCV manages to perpetuate itself both chronically in the individual and persistently in the population. The means by which these ends are achieved are founded in the elegant and robust structural mechanisms that HCV viral products use to survive and propagate in and among hosts. What follows is an examination of those structures and mechanisms that have been observed, although much remains to be explored.

STRUCTURE OF THE VIRION

Once serological identification of HCV and subsequent validation of anti-HCV antibodies was successful, immunogold-labeled HCV was positively identified under the electron microscope. Its smooth lipid-like surface and variable size are consistent with host apolipoparticles, leaving little wonder why initial attempts at visual identification failed (Catanese et al. 2013).

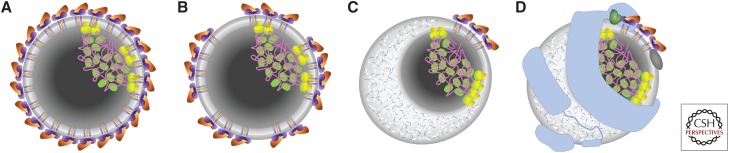

Co-expression of HCV structural proteins in a baculovirus system generated a size- and shape-heterogeneous population of purified particles from which a small set of isometric, 50-nm diameter particles was used to calculate an icosahedral reconstruction. Although limited in resolution (30 Å), the smooth surface was compared favorably to the icosahedrally ordered layer of envelope protein that is tightly associated with a lipid bilayer in related flavivirus structures that have been solved to near-atomic resolution (Yu et al. 2007). In this model, E1 and E2 together represent the discrete assembly unit, whereas other flaviviruses utilize a single E protein (Kuhn et al. 2002; Modis et al. 2003). The core protein was not observed as an icosahedrally ordered structure, suggesting that any nucleocapsid would be randomly oriented relative to the envelope protein as schematically shown in Figure 1A. This organization is inconsistent with the size and shape heterogeneity observed in that sample, so it might represent a special case within a diverse population. Nonconforming particles may simply represent more random packing of the envelope proteins (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Schematic representations of various models of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) virion. (A) Complete icosahedral shell of E1/E2 heterodimers (purple and orange, respectively), embedded in a lipid bilayer (gray), and including an asymmetrically localized condensate of lipid-embedded core protein (green/yellow) and genomic RNA (magenta). (B–D) Colors and nucleocapsid representation as in panel A. (B) Incomplete or nonicosahedral organization of the E1/E2 heterodimers, embedded in a lipid bilayer. (C) Partial dissociation of the lipid bilayer by cholesterol ester (white/blue) with clustering of E1/E2 heterodimers in the remaining lipid bilayer. (D) Inclusion of host apolipoproteins ApoAI (dark gray), ApoB-100 (light blue), and ApoE (green).

HCV virions from primary liver cells or Huh-7.5 cells were specifically concentrated onto coated EM grids via immunocapture (Catanese et al. 2013). Extensive size analysis under both negative stain and cryo conditions indicate a continuous distribution of diameters, mostly between 50 and 85 nm, but ranging from 40 to 100 nm. If this size heterogeneity were a result of polymorphism in an icosahedrally ordered system, then the diameter distribution would cluster into discrete modes, each correlated to a T number of quasi-equivalent environments for each assembly unit (Caspar 1980; Kellenberger 1990; Damle et al. 2012). As this is not the case, a more flexible model is indicated.

The continuously variable size of HCV virions may be a result of variable lipid content (Fig. 1C). The density of HCV virions ranges from 1.01 to 1.25 with infectivity associated with particles that have specific gravity of ∼1.12 g/mL (Lindenbach et al. 2005). This is consistent with the uniform exclusion of uranyl acetate from most virion particles in negative stain EM and with the lack of lipid bilayer structures in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) (Catanese et al. 2013).

Immunogold labeling identified apolipoproteins, ApoAI, ApoB, and ApoE, on the surface of HCV virions (Catanese et al. 2013), and some biochemical evidence indicates that ApoB and ApoE bind specifically to the ectodomain of E1 (Mazumdar et al. 2011). This further contraindicates an icosahedral envelope lattice as these host proteins would have to displace part of the viral protein lattice and are generally associated with lipoparticles rather than lipid bilayers. Immunocapture of HCV virions from Huh7.5 cells and from patient serum followed by negative stain showed similar internal structures not previously observed (Piver et al. 2017). Although these particles exhibit a number of staining and desiccation artifacts, absent in previous studies, this desiccation appears to have fortuitously granted stain the access to internal structures. Although particle sizes were not systematically measured, diameters appear to range from 50 to 200 nm in this sample, which may be attributed to RNA and lipid regions (Fig. 1D).

The emerging model of the HCV virion suggests that HCV evades the immune system while circulating in the blood by disguising itself as lipoparticles of approximate size and density of very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDLs). This model is consistent with the development of antibodies against apolipoproteins by people chronically infected with HCV (Bridge et al. 2018), the high rate of progression to chronic infection (70%–80%) (Alter et al. 1999), blood contact modes of transmission, and viral use of lipoparticle receptors for hepatocyte targeting (discussed below).

CORE

The viral core protein is a 191-amino-acid-long protein (21 kDa) and the first protein in the viral polyprotein. The amino-terminal domain, D1, is ∼120 residues long and condenses with the viral RNA genome to form the nucleocapsid (Fig. 1, green and magenta, respectively). Consistent with its RNA-binding function, D1 is nearly 20% arginine, but it is also high in glycine and proline (∼14% each) indicative of an intrinsically unstructured or elastomeric domain (Cheng et al. 2010). This has been observed experimentally, where recombinant D1 alone is disordered (Boulant et al. 2005). The carboxy-terminal domain, D2, is ∼50 residues long and associates with lipid droplets and ER membranes. Leucine and alanine account for 30% of the residues in D2, consistent with a hydrophobic domain. The last ∼20 residues serve as a signal sequence (SS) for the next protein, E1, and are cleaved from the core by an intramembrane-cleaving signal peptide peptidase after residue 177, yielding a mature size of ∼19 kDa (Fig. 2A; Kato et al. 2003; Lussignol et al. 2016).

Figure 2.

Structure and membrane association of core, E1, and E1 proteins. (A) A schematic of core (green/yellow), E1 (purple), and E2 (orange) proteins in association with the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane (gray). Residues are numbered at feature boundaries and signal peptide peptidase (SPP) cleavage is indicated (scissors). Unusual residue content is noted for the core amino-terminal domain and core carboxy-terminal domain and signal sequences (SSs), and transmembrane helices (TMs) are located in the ER membrane. Ribbon diagrams of three of six partial E1 ectodomain subunits are colored by chain (pink, purple, and dark purple, respectively) to indicate the two potential dimerization interfaces (PDB ID 4UOI). Superimposed ribbon diagrams of three successively larger E2 ectodomains show mutual consistency (orange, yellow, and white are PDB IDs 4WEB, 4MWF, and 6MEI, respectively). Ribbon diagrams of an E1 (B) and an E2 (C) ectodomain, rainbow colored from amino (blue) to carboxyl (red) termini with highly variable regions in white and boundary residues as marked.

The classical model for trafficking a nascent peptide to the ER involves an amino-terminal SS that forms a hydrophobic transmembrane (TM) helix. Briefly, the ribosome translates the SS, which is recognized by the signal recognition particle (SRP), temporarily pausing translation. The SRP binds to its receptor on the ER membrane and threads the SS into the channel of the Sec61 translocon. Translation continues and the SS is proteolytically removed (Ellgaard et al. 2016). The SS for E1 is identified by its hydrophobicity and proximity to the cleavage site, but it is also preceded by the hydrophobic D2 domain, which is predicted to contain another SS between residues 129 and 149. The guided entry of tail-anchored proteins (the GET pathway) was described in yeast (Wang et al. 2014). The Get3 homolog in humans, TRC40, inserts tail-anchored proteins in an ATP-dependent manner, leaving the amino-terminal domain(s) exposed to the cytosol (Stefanovic and Hegde 2007), and can deliver cargo to the Sec61 translocon (Johnson et al. 2012). Although this has not yet been tested for HCV proteins, herpesviruses EBV and HSV-1 have both been shown to exploit TRC40 for localization of their membrane-embedded proteins (Horst et al. 2011; Ott et al. 2016).

E1 ENVELOPE GLYCOPROTEIN

Viral envelope glycoprotein E1 (Figs. 1 and 2A, purple) is 192 amino acids long (21 kDa) after it has been proteolytically cleaved from the viral polyprotein between residues 192 and 383. The carboxy-terminal TM helix of the core protein, residues 178–191, is sufficient to target E1 to the lumen of the ER. The hairpin-helix-sheet of the amino-terminal ectodomain, residues 192–276 (Fig. 2B), was crystallized as a heavily entwined homohexamer with two different dimer interfaces. The ectodomain has an amino-terminal hairpin that dimerizes to form one dimer interface, and a helix and three-stranded β-sheet that forms the other (Fig. 2A, pink/dark purple and purple/dark purple, respectively; El Omari et al. 2014). A carboxy-terminal TM helix serves as the SS for the next protein E2 and then anchors E1 to the membrane. The intervening half of the protein, residues ∼271–363, is poorly characterized but does contain an absolutely conserved sequence, residues 313–327, which is targeted by a series of broadly neutralizing antibodies (Meunier et al. 2008; Kong et al. 2015) and a putative fusion loop, residues 265–296 (Banda et al. 2019).

E2 ENVELOPE GLYCOPROTEIN

The viral envelope glycoprotein E2 (Figs. 1 and 2A, orange) is a 363-amino-acid-long (40-kDa) protein, residues 384–746, and is reported to bind to receptors SR-BI and CD81 (discussed below). Like E1, it has an amino-terminal ectodomain (residues 384–661) and a carboxy-terminal TM helix, although in E2 these features are separated by an amphipathic stem helix, residues 662 on. The ectodomain includes three hypervariable regions (HVR1, HVR2, and HVR3, corresponding to residues 385–411, 475–481, and 556–580, respectively) to facilitate immune evasion, although HVR1 is disordered in existing structures (Flyak et al. 2018). Several crystal structures have been determined for most of the E2 ectodomain (Kong et al. 2013; Khan et al. 2014; Flyak et al. 2018), residues 422–591, and all are in good agreement (Fig. 2A). This portion of the protein adopts an Ig-like β sandwich, stabilized by disulfide bonds, and HVR2 and HVR3 are surface exposed (Fig. 2C).

DIMERIZATION MODELS OF E1 AND E2

The E1/E2 heterodimer was proposed on the basis of familial ties to the better-studied flaviviruses such as dengue. Such viruses have a single, 53-kDa envelope protein (E) that is embedded in an envelope bilayer forming a complete, icosahedrally ordered shell of uniform diameter (Kuhn et al. 2002). The combined molecular weights of E1 and E2 (∼61 kDa) is attractively close to this size, and overexpression of these proteins can occasionally form icosahedra; however, coexpressed E1/E2 tends to aggregate (Cocquerel et al. 2003).

DIVISION OF LABOR BETWEEN THE TWO PROTEINS

Generally, an enveloped virus requires that its outer surface provide three functions: evade the immune system, identify an appropriate host cell through receptor binding, and delivery of the nucleocapsid to the cell through membrane fusion. That immune evasion is aided by virus association with host lipoparticles was discussed above, and receptor binding will be discussed below, but first will be a comment about membrane fusion.

E2 was assigned the role of type II fusion protein modeled on the basis of disulfide links (Krey et al. 2010) until the structures were determined (Kong et al. 2013; Khan et al. 2014; Flyak et al. 2018). Then, by exclusion, E1 was assigned this role. Again, the structure determined that the E1 ectodomain was inconsistent with a type II fusion protein (El Omari et al. 2014). A significant part of the E1 protein was absent in the structure solved, which includes a putative fusion loop. However, perhaps additional mechanisms should be considered.

CD81

HCV requires multiple factors for productive entry (Lindenbach and Rice 2013). However, only CD81 and SR-BI have been shown to directly interact with E2 (Pileri et al. 1998; Scarselli et al. 2002). CD81 is an integral membrane protein of the tetraspanin family that contains four TM helices and two extracellular loops, designated as the small and large extracellular loop (SEL and LEL, respectively). CD81 has been shown to be important for HCV entry by RNAi knockdown experiments as well as entry inhibition by addition of exogenous CD81-LEL or antibodies against CD81 (Zhang et al. 2004; Flint et al. 2006). Given that CD81 is widely expressed in a variety of cells, it does not explain the liver tropism of HCV and may function after initial recruitment of the virus on the host cell. In the liver, CD81 is expressed on both the sinusoidal endothelium and the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes (Reynolds et al. 2008) The CD81-binding site for E2 has been localized to the LEL and specific residues essential for the interaction have been identified (Higginbottom et al. 2000; Drummer et al. 2002). Although the LEL appears to be the major recognition site for E2, regions outside of the LEL can influence HCV susceptibility into hepatoma cells (Banse et al. 2018).

Initial structural and biophysical studies were focused on the CD81 LEL, owing to the important role it has in HCV entry (Kitadokoro et al. 2001, 2002). CD81 LEL forms a dimer in solution and in several different crystal forms. The CD81 LEL domain organization has been likened to a mushroom-like structure formed by five helices (labeled A–E) with helices A and E forming the stalk, whereas helices B, C, and D represent the cap. The LEL contains two disulfides that stabilize the fold. The absolutely conserved CCG motif (residues 156–158) of the LEL located on the B–C loop forms two disulfides with residue 190 of helix E and residue 175 on the C–D loop. Mutating the disulfides destabilizes the CD81-LEL conformation and diminishes E2 binding (Petracca et al. 2000).

The E2-binding site has been localized to the cap region consisting of the C and D helices as well as the intervening loop. Comparison of several hCD81-LEL structures revealed that the C and D helices can undergo conformational fluctuations, whereas the conformation of stalk helices remains relatively fixed. Solution-based nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) study of hCD81-LEL confirmed the existence of A, B, C, and E helices, whereas the D helix was mostly disordered (Rajesh et al. 2012). Furthermore, analysis of 15 independent views of CD81 LEL across several different structures determined by X-ray crystallography have shown the C and D helices in at least three distinct conformations: open, closed, and intermediate (Cunha et al. 2017). Molecular dynamic simulations suggest that the state of the head group was pH dependent with the open conformation being more prevalent at low pH. This flexibility may be a result of the orientation of the conserved C157–C175 disulfide bond, which is found in multiple conformations. The authors proposed that the conformational flexibility of the head region may be exploited by HCV during endosomal acidification in the entry process. The current evidence suggests that CD81–E2 interaction is based upon flexible regions of both molecules that adopt a more ordered structure upon binding.

Recently, the structure of the full-length CD81 was determined by X-ray crystallography (Zimmerman et al. 2016). To assist in protein production, the intracellular cysteine residues that are sites of palmitoylation were mutated and the resulting protein was produced and crystallized in the presence of detergent and cholesterol. The overall structure resembles a waffle cone with the LEL covering the four TM helices, which form a wedge shape. The TMs are arranged as two separated pairs of antiparallel helices: TM1/TM2 and the other TM3/TM4. The organization of the TMs does not resemble any known integral membrane protein structure. This arrangement of TMs results in the formation of a large cavity containing additional electron density, which was identified as a single, bound cholesterol molecule.

The full-length CD81 structure consists of a monomer in the asymmetric unit. Superposition of the CD81 LEL dimeric structure onto the full-length structure results in a clash between the second LEL molecule and the TMs of the full-length structure. This clash would suggest that the dimeric LEL may be a biochemical artifact. However, molecular dynamics simulation of the full-length structure in the absence of cholesterol suggested that the LEL would be in an extended open conformation, which may expose the LEL dimer interface (Fig. 3). However, because the LEL dimer is in a head-to-tail orientation, the second CD81 molecule would need to be in an orientation that would not be consistent with a flat membrane. Therefore, the membrane would need to be curved or, alternatively, the second molecule could come from another cell.

Figure 3.

Structure of CD81 with emphasis on the large extracellular loop (LEL). (A) The CD81 LEL forms a dimer in solution as well as in several crystals forms. A ribbon representation of the CD81 LEL dimer (PDB ID 1G8Q) with the individual molecules colored gray and in a rainbow from the amino terminus (blue) to the carboxyl terminus (red). The two disulfides are shown as sticks. Helices C and D as well as the intervening loop have been implicated in recognizing HCV E2. The LEL forms a head-to-tail dimer with the E2-binding sites on opposite ends of the complex. (B) The LEL dimeric interface with one molecule shown in a ribbon representation similar to panel A, whereas the second molecule is a surface rendition colored for electrostatic potential (red for negative, blue for positive, and white for neutral). (C) Ribbon rendition of the full-length, human CD81 structure (PDB ID 5TCX) modeled approximately on to an idealized lipid bilayer (stick representation) (a simulated dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine bilayer). The transmembrane (TM) helices are colored beige, whereas the LEL is colored as a rainbow. The small extracellular loop (SEL) is located between TM helices 1 and 2, while the LEL is located between TMs 3 and 4. The five helices in the LEL are labeled A–E. The SEL is present in the crystallization construct, but disordered. Cholesterol from the crystallization solution is rendered as a space-filled model (left). A single molecule of bound cholesterol is shown in a sphere representation between the four TMs. (D) Superposition of the full-length CD81 structure (beige) with the LEL dimer colored blue and green for the two molecules in the asymmetric unit. (E) The LEL of the full-length CD81 has been proposed to undergo an open-to-closed transition upon cholesterol (green ligand) binding, the reverse of a closed-to-open transition modeled using molecular dynamics (Zimmerman et al. 2016). The coloring used is similar to panel A.

SR-BI

SR-BI is the high-density lipoprotein (HDL) receptor whose primary role is to mediate uptake of cholesteryl esters from HDL to the cell without internalization of the particle (Pittman et al. 1987). SR-BI has hepatocyte specific expression, suggesting a possible role in primary attachment to the target cells. HDL has been shown to enhance infectivity of HCV pseudoparticles (HCVpp) and HCV virions derived from cell culture (HCVcc) (Dreux et al. 2006; Voisset et al. 2006). Furthermore, antibodies against SR-BI, siRNA-mediated knockdown, and mutations to the intracellular and ectodomain of SR-BI result in a significant inhibition of HCV infectivity (Bartosch et al. 2003; Dreux et al. 2009). The region of E2 responsible for SR-BI binding has been mapped to HVR1 of E2 (Bartosch et al. 2005). It has been hypothesized that binding of SR-BI to E2 enhances CD81 binding (Bankwitz et al. 2010). Therefore, HVR1 region has been proposed to conceal the CD81-binding site and to block conserved epitopes mediating virus neutralization on E2 (Bankwitz et al. 2010).

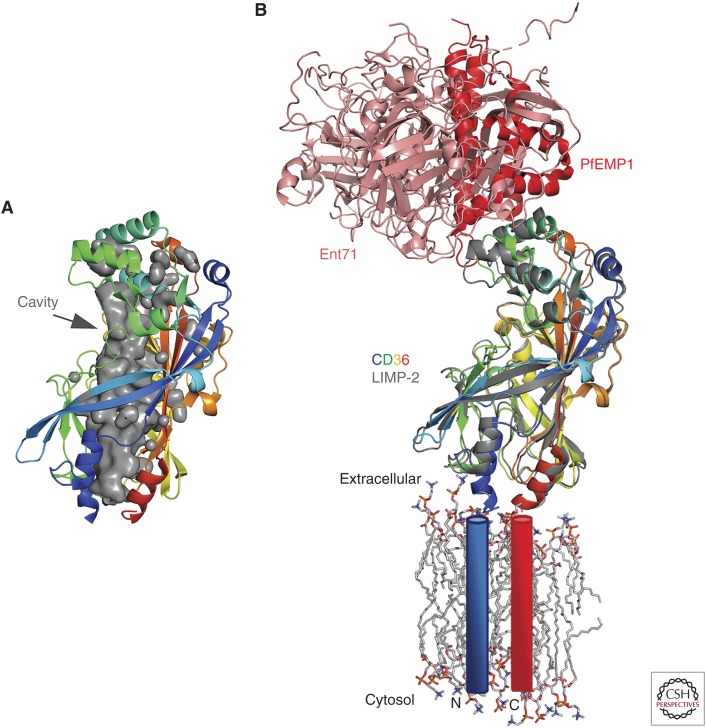

SR-BI is a member of the class B scavenger receptor family of proteins, which also includes CD36 and the lysosomal integral membrane protein-2 (LIMP-2) also referred to scavenger receptor class B member 2 (SCARB2). SR-BI is a type III membrane protein with amino- and carboxy-terminal TM helices with both termini located in the cytoplasm. The majority of the protein is located between the TMs, forming a large extracellular domain. Currently, structural information on SR-BI is lacking; however, models can be predicted from several, published structures of LIMP-2 and CD36 ectodomains (Neculai et al. 2013; Dang et al. 2014; Zhao et al. 2014; Hsieh et al. 2016; Zhou et al. 2019). LIMP-2 and CD36 have an overall globular shape formed by a 13-stranded antiparallel β-barrel with several short α-helices on the periphery. The SR-BI ectodomain is heavily modified post translation with 10 predicted N-linked glycosylation sites and two disulfide bonds (C321–C323, C274–C329). The two disulfide bonds are conserved in CD36 and LIMP-2, suggesting that these are critical for the overall fold. However, only one glycosylation site is conserved among the three proteins, which may reflect their different biological functions.

A remarkable feature of the structures is the presence of an internal tunnel that traverses the entire length of the ectodomain from the lipid bilayer to a solvent opening close on the apex (Fig. 4A). The tunnel has been proposed to mediate selective lipid uptake from HDL and efflux of cellular cholesterol to HDL transport lipids. Block lipid transport 1 (BLT-1) is a small-molecule inhibitor of lipid transport by SR-BI that covalently modifies C384 (Nieland et al. 2002; Yu et al. 2011). C384 is located in the lumen of the tunnel and the addition of a BLT-1 compound is expected to impede the transit of cholesterol. Furthermore, several of these structures contain various compounds in the tunnel, including PEG, phospholipids, and cholesterol.

Figure 4.

Structure of scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) homologs, CD36, and lysosomal integral membrane protein-2 (LIMP-2). (A) Ribbon representation of LIMP-2 with a gray surface highlighting a solvent-exposed cavity that traverses the protein from extracellular to the cell membrane. (B) Superposition of CD36 bound to PfEMP1 (PDB ID 5LGD) and LIMP-2 complexed with EV71 (PDB ID 6I2K). LIMP-2 is rainbow colored from the amino (blue) to the carboxyl (red) termini similar to panel A, whereas pfEMP1, EV71, and CD36 are colored red, pink, and gray, respectively. The structures are modeled on to an idealized lipid bilayer with the TMs. The lipid bilayer and amino-linked glycans are shown in a stick representation, whereas the TMs are approximated by blue (amino-terminal) and red (carboxy-terminal) cylinders.

In addition to HCV, other human pathogens have exploited this class of proteins as attachment or entry factors. In this review, we will focus specifically on recent structures of LIMP-2/SCARB2 complexed with the enterovirus 71 (EV71) virion (Zhou et al. 2019) and CD36 bound to the malarial protein Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) (Fig. 4B; Hsieh et al. 2016). LIMP-2 is a receptor or entry factor for several enteroviruses. EV71 infection causes hand, foot, and mouth disease. A structure of the LIMP-2 ectodomain bound to a pH-adapted EV71 mutant virus (N104S of VP1) and in the presence of a pocket factor inhibitor was determined by high-resolution cryo-EM. The viral capsid proteins, VP1 and VP2, engage with two α helices (α5 α7) at the apex of LIMP-2 distal from the membrane (>50 Å distance). This helical bundle undergoes pH-dependent conformational changes, which have been proposed to trigger release of the RNA genome (Dang et al. 2014). The model proposes that EV71 binds to LIMP-2 and is shuttled to the endosomal. Endosomal acidification activates the LIMP-2 lipid transport tunnel, causes the removal of the lipid pocket factor, and triggers capsid uncoating. PfEMP1 is an adhesive protein expressed on the surface on an infected red blood cell, which will adhere to blood vesicles and tissues. PfEMP1 are large proteins (>200 kDa) with the extracellular portion contain one to two copies of cysteine-rich interdomain region (CIDR) domains. Interestingly, PfEMP1 binds CD36 in an overlapping region as EV71 to CD36 (Fig. 4B). Unlike LIMP-2, CD36 is not known to undergo pH-dependent conformational changes as the critical pH-sensing histidine residue is not conserved. It is interesting to place these results in the context of HCV infection mediated by SR-BI. The amino-terminal portion of HCV E2 would engage the apical region of SR-BI and activate the lipid transfer tunnel to transfer cholesterol from the lipoviral particle to the cell stimulated by endosomal acidification. This could trigger fusion between the virion and cell membranes causing the release of the HCV genome into the cytoplasm.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

HCV is a unique virus. It does not meet the expectations established by comparison with its better-studied relatives in the flavivirus family and so, perhaps, HCV employs a novel mechanism of entry. E2 has been shown to bind to host cell receptors, CD81 and SR-BI, and pH is important as p7 regulates it during egress (Bentham et al. 2013); but how pH is sensed after endocytosis remains unknown. Other flaviviruses have a lipid bilayer, entirely covered by viral envelope protein, and use a type II fusion protein to join the host and viral membranes. HCV might lack a type II fusion protein because it may lack a well-defined lipid bilayer. Because the virus particle is coated in a variable layer of lipid and apolipoproteins, the mechanics of fusion would have to be different from a bilayer, although that mechanism remains unknown. Whether HCV has a fusion protein at all should also be considered. Comparisons between viruses have long been a fruitful means of hypothesis generation, but this is predicated on the viruses actually having enough in common to draw parallels. Considering the greater similarity of HCV to lipoparticles than to flaviviruses, perhaps the mechanisms of lipid homeostasis hold the key to how HCV accomplishes infection. If we learn what to look for, perhaps we will find more viruses like HCV, hiding in plain sight.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (A.D.D. and J.M.) and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (A.D.D.).

Footnotes

Editors: Arash Grakoui, Jean-Michel Pawlotsky, and Glenn Randall

Additional Perspectives on Hepatitis C Viruses: The Story of a Scientific and Therapeutic Revolution available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F, Moyer LA, Kaslow RA, Margolis HS. 1999. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med 341: 556–562. 10.1056/NEJM199908193410802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banda DH, Perin PM, Brown RJP, Todt D, Solodenko W, Hoffmeyer P, Kumar Sahu K, Houghton M, Meuleman P, Muller R, et al. 2019. A central hydrophobic E1 region controls the pH range of hepatitis C virus membrane fusion and susceptibility to fusion inhibitors. J Hepatol 70: 1082–1092. 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.01.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankwitz D, Steinmann E, Bitzegeio J, Ciesek S, Friesland M, Herrmann E, Zeisel MB, Baumert TF, Keck ZY, Foung SK, et al. 2010. Hepatitis C virus hypervariable region 1 modulates receptor interactions, conceals the CD81 binding site, and protects conserved neutralizing epitopes. J Virol 84: 5751–5763. 10.1128/JVI.02200-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banse P, Moeller R, Bruening J, Lasswitz L, Kahl S, Khan AG, Marcotrigiano J, Pietschmann T, Gerold G. 2018. CD81 receptor regions outside the large extracellular loop determine hepatitis C virus entry into hepatoma cells. Viruses 10: 207 10.3390/v10040207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosch B, Vitelli A, Granier C, Goujon C, Dubuisson J, Pascale S, Scarselli E, Cortese R, Nicosia A, Cosset FL. 2003. Cell entry of hepatitis C virus requires a set of co-receptors that include the CD81 tetraspanin and the SR-B1 scavenger receptor. J Biol Chem 278: 41624–41630. 10.1074/jbc.M305289200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartosch S, Woodmansey EJ, Paterson JC, McMurdo ME, Macfarlane GT. 2005. Microbiological effects of consuming a synbiotic containing Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium lactis, and oligofructose in elderly persons, determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction and counting of viable bacteria. Clin Infect Dis 40: 28–37. 10.1086/426027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentham MJ, Foster TL, McCormick C, Griffin S. 2013. Mutations in hepatitis C virus p7 reduce both the egress and infectivity of assembled particles via impaired proton channel function. J Gen Virol 94: 2236–2248. 10.1099/vir.0.054338-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulant S, Vanbelle C, Ebel C, Penin F, Lavergne JP. 2005. Hepatitis C virus core protein is a dimeric α-helical protein exhibiting membrane protein features. J Virol 79: 11353–11365. 10.1128/JVI.79.17.11353-11365.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge SH, Pagano S, Jones M, Foster GR, Neely D, Vuilleumier N, Bassendine MF. 2018. Autoantibody to apolipoprotein A-1 in hepatitis C virus infection: A role in atherosclerosis? Hepatol Int 12: 17–25. 10.1007/s12072-018-9842-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt AA, Yan P, Chew KW, Currier J, Corey K, Chung RT, Shuaib A, Abou-Samra AB, Butler J, Freiberg MS. 2017. Risk of acute myocardial infarction among hepatitis C virus (HCV)-positive and HCV-negative men at various lipid levels: Results from ERCHIVES. Clin Infect Dis 65: 557–565. 10.1093/cid/cix359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso H, Vale AM, Rodrigues S, Goncalves R, Albuquerque A, Pereira P, Lopes S, Silva M, Andrade P, Morais R, et al. 2016. High incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma following successful interferon-free antiviral therapy for hepatitis C associated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 65: 1070–1071. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspar DL. 1980. Movement and self-control in protein assemblies. Quasi-equivalence revisited. Biophys J 32: 103–138. 10.1016/S0006-3495(80)84929-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanese MT, Uryu K, Kopp M, Edwards TJ, Andrus L, Rice WJ, Silvestry M, Kuhn RJ, Rice CM. 2013. Ultrastructural analysis of hepatitis C virus particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 9505–9510. 10.1073/pnas.1307527110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Cetinkaya M, Gräter F. 2010. How sequence determines elasticity of disordered proteins. Biophys J 99: 3863–3869. 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocquerel L, Kuo CC, Dubuisson J, Levy S. 2003. CD81-dependent binding of hepatitis C virus E1E2 heterodimers. J Virol 77: 10677–10683. 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10677-10683.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti F, Buonfiglioli F, Scuteri A, Crespi C, Bolondi L, Caraceni P, Foschi FG, Lenzi M, Mazzella G, Verucchi G, et al. 2016. Early occurrence and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antivirals. J Hepatol 65: 727–733. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha ES, Sfriso P, Rojas AL, Roversi P, Hospital A, Orozco M, Abrescia NGA. 2017. Mechanism of structural tuning of the hepatitis C virus human cellular receptor CD81 large extracellular loop. Structure 25: 53–65. 10.1016/j.str.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damle PK, Wall EA, Spilman MS, Dearborn AD, Ram G, Novick RP, Dokland T, Christie GE. 2012. The roles of SaPI1 proteins gp7 (CpmA) and gp6 (CpmB) in capsid size determination and helper phage interference. Virology 432: 277–282. 10.1016/j.virol.2012.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang M, Wang X, Wang Q, Wang Y, Lin J, Sun Y, Li X, Zhang L, Lou Z, Wang J, et al. 2014. Molecular mechanism of SCARB2-mediated attachment and uncoating of EV71. Protein Cell 5: 692–703. 10.1007/s13238-014-0087-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreux M, Pietschmann T, Granier C, Voisset C, Ricard-Blum S, Mangeot PE, Keck Z, Foung S, Vu-Dac N, Dubuisson J, et al. 2006. High density lipoprotein inhibits hepatitis C virus-neutralizing antibodies by stimulating cell entry via activation of the scavenger receptor BI. J Biol Chem 281: 18285–18295. 10.1074/jbc.M602706200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreux M, Dao Thi VL, Fresquet J, Guérin M, Julia Z, Verney G, Durantel D, Zoulim F, Lavillette D, Cosset FL, et al. 2009. Receptor complementation and mutagenesis reveal SR-BI as an essential HCV entry factor and functionally imply its intra- and extra-cellular domains. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000310 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummer HE, Wilson KA, Poumbourios P. 2002. Identification of the hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein binding site on the large extracellular loop of CD81. J Virol 76: 11143–11147. 10.1128/JVI.76.21.11143-11147.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egro FM, Nwaiwu CA, Smith S, Harper JD, Spiess AM. 2017. Seroconversion rates among health care workers exposed to hepatitis C virus–contaminated body fluids: The University of Pittsburgh 13-year experience. Am J Infect Control 45: 1001–1005. 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellgaard L, McCaul N, Chatsisvili A, Braakman I. 2016. Co- and post-translational protein folding in the ER. Traffic 17: 615–638. 10.1111/tra.12392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Omari K, Iourin O, Kadlec J, Sutton G, Harlos K, Grimes JM, Stuart DI. 2014. Unexpected structure for the N-terminal domain of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E1. Nat Commun 5: 4874 10.1038/ncomms5874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint M, von Hahn T, Zhang J, Farquhar M, Jones CT, Balfe P, Rice CM, McKeating JA. 2006. Diverse CD81 proteins support hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol 80: 11331–11342. 10.1128/JVI.00104-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flyak AI, Ruiz S, Colbert MD, Luong T, Crowe JE Jr, Bailey JR, Bjorkman PJ. 2018. HCV broadly neutralizing antibodies use a CDRH3 disulfide motif to recognize an E2 glycoprotein site that can be targeted for vaccine design. Cell Host Microbe 24: 703–716.e3. 10.1016/j.chom.2018.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarino M, Sessa A, Cossiga V, Morando F, Caporaso N, Morisco F; Special Interest Group on “Hepatocellular carcinoma and new anti-HCV therapies” of the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2018. Direct-acting antivirals and hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C: A few lights and many shadows. World J Gastroenterol 24: 2582–2595. 10.3748/wjg.v24.i24.2582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginbottom A, Quinn ER, Kuo CC, Flint M, Wilson LH, Bianchi E, Nicosia A, Monk PN, McKeating JA, Levy S. 2000. Identification of amino acid residues in CD81 critical for interaction with hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E2. J Virol 74: 3642–3649. 10.1128/JVI.74.8.3642-3649.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PV, Alter HJ. 1981. Non-A, non-B viral hepatitis. Hum Pathol 12: 1114–1122. 10.1016/S0046-8177(81)80332-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horst D, Favaloro V, Vilardi F, van Leeuwen HC, Garstka MA, Hislop AD, Rabu C, Kremmer E, Rickinson AB, High S, et al. 2011. EBV protein BNLF2a exploits host tail-anchored protein integration machinery to inhibit TAP. J Immunol 186: 3594–3605. 10.4049/jimmunol.1002656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoglu S, Celen MK, Akalin S, Geyik MF, Soyoral Y, Kara IH. 2003. Transmission of hepatitis C by blood splash into conjunctiva in a nurse. Am J Infect Control 31: 502–504. 10.1016/j.ajic.2003.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh FL, Turner L, Bolla JR, Robinson CV, Lavstsen T, Higgins MK. 2016. The structural basis for CD36 binding by the malaria parasite. Nat Commun 7: 12837 10.1038/ncomms12837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N, Vilardi F, Lang S, Leznicki P, Zimmermann R, High S. 2012. TRC40 can deliver short secretory proteins to the Sec61 translocon. J Cell Sci 125: 3612–3620. 10.1242/jcs.102608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Miyamoto M, Furusaka A, Date T, Yasui K, Kato J, Matsushima S, Komatsu T, Wakita T. 2003. Processing of hepatitis C virus core protein is regulated by its C-terminal sequence. J Med Virol 69: 357–366. 10.1002/jmv.10297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellenberger E. 1990. Form determination of the heads of bacteriophages. Eur J Biochem 190: 233–248. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15568.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AG, Whidby J, Miller MT, Scarborough H, Zatorski AV, Cygan A, Price AA, Yost SA, Bohannon CD, Jacob J, et al. 2014. Structure of the core ectodomain of the hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein 2. Nature 509: 381–384. 10.1038/nature13117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitadokoro K, Bordo D, Galli G, Petracca R, Falugi F, Abrignani S, Grandi G, Bolognesi M. 2001. CD81 extracellular domain 3D structure: Insight into the tetraspanin superfamily structural motifs. EMBO J 20: 12–18. 10.1093/emboj/20.1.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitadokoro K, Ponassi M, Galli G, Petracca R, Falugi F, Grandi G, Bolognesi M. 2002. Subunit association and conformational flexibility in the head subdomain of human CD81 large extracellular loop. Biol Chem 383: 1447–1452. 10.1515/BC.2002.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Giang E, Nieusma T, Kadam RU, Cogburn KE, Hua Y, Dai X, Stanfield RL, Burton DR, Ward AB, et al. 2013. Hepatitis C virus E2 envelope glycoprotein core structure. Science 342: 1090–1094. 10.1126/science.1243876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Kadam RU, Giang E, Ruwona TB, Nieusma T, Culhane JC, Stanfield RL, Dawson PE, Wilson IA, Law M. 2015. Structure of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E1 antigenic site 314-324 in complex with antibody IGH526. J Mol Biol 427: 2617–2628. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krey T, d'Alayer J, Kikuti CM, Saulnier A, Damier-Piolle L, Petitpas I, Johansson DX, Tawar RG, Baron B, Robert B, et al. 2010. The disulfide bonds in glycoprotein E2 of hepatitis C virus reveal the tertiary organization of the molecule. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000762 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn RJ, Zhang W, Rossmann MG, Pletnev SV, Corver J, Lenches E, Jones CT, Mukhopadhyay S, Chipman PR, Strauss EG, et al. 2002. Structure of dengue virus: Implications for flavivirus organization, maturation, and fusion. Cell 108: 717–725. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00660-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenbach BD, Rice CM. 2013. The ins and outs of hepatitis C virus entry and assembly. Nat Rev Microbiol 11: 688–700. 10.1038/nrmicro3098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wölk B, Tellinghuisen TL, Liu CC, Maruyama T, Hynes RO, Burton DR, McKeating JA, et al. 2005. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 309: 623–626. 10.1126/science.1114016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussignol M, Kopp M, Molloy K, Vizcay-Barrena M, Fleck RA, Dorner M, Bell KL, Chait BT, Rice CM, Catanese MT. 2016. Proteomics of HCV virions reveals an essential role for the nucleoporin Nup98 in virus morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 113: 2484–2489. 10.1073/pnas.1518934113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumdar B, Banerjee A, Meyer K, Ray R. 2011. Hepatitis C virus E1 envelope glycoprotein interacts with apolipoproteins in facilitating entry into hepatocytes. Hepatology 54: 1149–1156. 10.1002/hep.24523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier JC, Russell RS, Goossens V, Priem S, Walter H, Depla E, Union A, Faulk KN, Bukh J, Emerson SU, et al. 2008. Isolation and characterization of broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to the e1 glycoprotein of hepatitis C virus. J Virol 82: 966–973. 10.1128/JVI.01872-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modis Y, Ogata S, Clements D, Harrison SC. 2003. A ligand-binding pocket in the dengue virus envelope glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 6986–6991. 10.1073/pnas.0832193100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KJ, Gauri A, Koru-Sengul T. 2019. Prevalence and sociodemographic disparities of hepatitis C in baby boomers and the US adult population. J Infect Public Health 12: 32–36. 10.1016/j.jiph.2018.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neculai D, Schwake M, Ravichandran M, Zunke F, Collins RF, Peters J, Neculai M, Plumb J, Loppnau P, Pizarro JC, et al. 2013. Structure of LIMP-2 provides functional insights with implications for SR-BI and CD36. Nature 504: 172–176. 10.1038/nature12684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, Layden TJ, Perelson AS. 1998. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-α therapy. Science 282: 103–107. 10.1126/science.282.5386.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieland TJ, Penman M, Dori L, Krieger M, Kirchhausen T. 2002. Discovery of chemical inhibitors of the selective transfer of lipids mediated by the HDL receptor SR-BI. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 15422–15427. 10.1073/pnas.222421399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott M, Marques D, Funk C, Bailer SM. 2016. Asna1/TRC40 that mediates membrane insertion of tail-anchored proteins is required for efficient release of herpes simplex virus 1 virions. Virol J 13: 175 10.1186/s12985-016-0638-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petracca R, Falugi F, Galli G, Norais N, Rosa D, Campagnoli S, Burgio V, Di Stasio E, Giardina B, Houghton M, et al. 2000. Structure–function analysis of hepatitis C virus envelope-CD81 binding. J Virol 74: 4824–4830. 10.1128/JVI.74.10.4824-4830.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pileri P, Uematsu Y, Campagnoli S, Galli G, Falugi F, Petracca R, Weiner AJ, Houghton M, Rosa D, Grandi G, et al. 1998. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science 282: 938–941. 10.1126/science.282.5390.938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittman RC, Knecht TP, Rosenbaum MS, Taylor CA Jr. 1987. A nonendocytotic mechanism for the selective uptake of high density lipoprotein-associated cholesterol esters. J Biol Chem 262: 2443–2450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piver E, Boyer A, Gaillard J, Bull A, Beaumont E, Roingeard P, Meunier JC. 2017. Ultrastructural organisation of HCV from the bloodstream of infected patients revealed by electron microscopy after specific immunocapture. Gut 66: 1487–1495. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh S, Sridhar P, Tews BA, Fénéant L, Cocquerel L, Ward DG, Berditchevski F, Overduin M. 2012. Structural basis of ligand interactions of the large extracellular domain of tetraspanin CD81. J Virol 86: 9606–9616. 10.1128/JVI.00559-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reig M, Mariño Z, Perelló C, Iñarrairaegui M, Ribeiro A, Lens S, Díaz A, Vilana R, Darnell A, Varela M, et al. 2016a. Unexpected high rate of early tumor recurrence in patients with HCV-related HCC undergoing interferon-free therapy. J Hepatol 65: 719–726. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reig M, Torres F, Mariño Z, Forns X, Bruix J. 2016b. Reply to “Direct antiviral agents and risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) early recurrence: Much ado about nothing.” J Hepatol 65: 864–865. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds GM, Harris HJ, Jennings A, Hu K, Grove J, Lalor PF, Adams DH, Balfe P, Hübscher SG, McKeating JA. 2008. Hepatitis C virus receptor expression in normal and diseased liver tissue. Hepatology 47: 418–427. 10.1002/hep.22028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarselli E, Ansuini H, Cerino R, Roccasecca RM, Acali S, Filocamo G, Traboni C, Nicosia A, Cortese R, Vitelli A. 2002. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J 21: 5017–5025. 10.1093/emboj/cdf529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman ML. 2018. The next wave of hepatitis C virus: The epidemic of intravenous drug use. Liver Int 38 (Suppl. 1): 34–39. 10.1111/liv.13647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanovic S, Hegde RS. 2007. Identification of a targeting factor for posttranslational membrane protein insertion into the ER. Cell 128: 1147–1159. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targher G, Bertolini L, Padovani R, Rodella S, Arcaro G, Day C. 2007. Differences and similarities in early atherosclerosis between patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and chronic hepatitis B and C. J Hepatol 46: 1126–1132. 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitvitski L, Trepo C, Prince AM, Brotman B. 1979. Detection of virus-associated antigen in serum and liver of patients with non-A non-B hepatitis. Lancet 314: 1263–1267. 10.1016/S0140-6736(79)92280-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisset C, de Beeck A O, Horellou P, Dreux M, Gustot T, Duverlie G, Cosset FL, Vu-Dac N, Dubuisson J. 2006. High-density lipoproteins reduce the neutralizing effect of hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patient antibodies by promoting HCV entry. J Gen Virol 87: 2577–2581. 10.1099/vir.0.81932-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Chan C, Weir NR, Denic V. 2014. The Get1/2 transmembrane complex is an endoplasmic-reticulum membrane protein insertase. Nature 512: 441–444. 10.1038/nature13471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams I. 1999. Epidemiology of hepatitis C in the United States. Am J Med 107: 2–9. 10.1016/S0002-9343(99)00373-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Qiao M, Atanasov I, Hu Z, Kato T, Liang TJ, Zhou ZH. 2007. Cryo-electron microscopy and three-dimensional reconstructions of hepatitis C virus particles. Virology 367: 126–134. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Romer KA, Nieland TJ, Xu S, Saenz-Vash V, Penman M, Yesilaltay A, Carr SA, Krieger M. 2011. Exoplasmic cysteine Cys384 of the HDL receptor SR-BI is critical for its sensitivity to a small-molecule inhibitor and normal lipid transport activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 12243–12248. 10.1073/pnas.1109078108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Randall G, Higginbottom A, Monk P, Rice CM, McKeating JA. 2004. CD81 is required for hepatitis C virus glycoprotein-mediated viral infection. J Virol 78: 1448–1455. 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1448-1455.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Sheng J, Plevka P, Kuhn RJ, Diamond MS, Rossmann MG. 2013. Dengue structure differs at the temperatures of its human and mosquito hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 6795–6799. 10.1073/pnas.1304300110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Ren J, Padilla-Parra S, Fry EE, Stuart DI. 2014. Lysosome sorting of β-glucocerebrosidase by LIMP-2 is targeted by the mannose 6-phosphate receptor. Nat Commun 5: 4321 10.1038/ncomms5321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Zhao Y, Kotecha A, Fry EE, Kelly JT, Wang X, Rao Z, Rowlands DJ, Ren J, Stuart DI. 2019. Unexpected mode of engagement between enterovirus 71 and its receptor SCARB2. Nat Microbiol 4: 414–419. 10.1038/s41564-018-0319-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman B, Kelly B, McMillan BJ, Seegar TCM, Dror RO, Kruse AC, Blacklow SC. 2016. Crystal structure of a full-length human tetraspanin reveals a cholesterol-binding pocket. Cell 167: 1041–1051.e11. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.09.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]