Abstract

Background

Sex hormones are important in female sexual physiology, growth, and homeostasis. Through skin receptors, sex hormones contribute to the dermatologic pathology known as catamenial dermatoses.

Objective

This study aims to summarize the literature on catamenial dermatoses and menses-induced exacerbations of chronic dermatoses.

Methods

This systematic review used the PRISMA method. PubMed was searched using the terms “menses” and “skin” in July 2018, and an assessment was conducted of the relevant literature on skin diseases related to non-pathologic menstruation, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome. Pathology associated with androgenetic acne was excluded from the study.

Results

A total of 102 studies with 1269 female patients were included. The most commonly reported primary catamenial dermatoses were autoimmune progesterone dermatitis and autoimmune estrogen dermatitis. The most commonly reported chronic skin disorders exacerbated by menses were psoriasis, Behcet’s disease, and eczematous dermatoses.

Conclusion

Physicians should be aware of the nature of catamenial dermatoses and their presentation with normal sexual physiology. Patients with chronic dermatoses should be appropriately counseled on menstruation-related exacerbations. Further research needs to be conducted to determine the interplay between immune regulation and sex hormones in catamenial dermatoses and to elucidate effective therapies.

Keywords: Catamenial, Menses, Menstruation, Menstrual cycle, Autoimmune, Progesterone, Estrogen, Dermatoses

Introduction

The monthly ovarian cycle is characterized by tightly regulated hormones predictably fluctuating throughout the reproductive years. The menstrual cycle plays a role in the exacerbation of rheumatologic conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus, with flares occurring prior to and during menses, respectively (Colangelo et al., 2011, Latman, 1983). Given these previous observations, sex hormones are hypothesized to influence the biologic properties of the immune system and skin.

This systematic review aims to catalog the available evidence with regard to skin pathologies occurring in conjunction with menstrual periods, also known as catamenial dermatoses.

Menstrual cycle, sex hormones receptors, and the skin

Circulating sex hormones (i.e., estrogens, progesterone, and androgens) regulate skin homeostasis. Thus, cutaneous disease may be influenced by the menstrual cycle, specifically by hormonal modulation of skin cell activity (Hermanns-Le et al., 2013). The menstrual cycle is split into two phases: the follicular phase (dominated by estradiol) and the luteal phase (dominated by progesterone). Initially, increased levels of estrogens and androgens at the end of the follicular phase and periovulation cause skin sebum production, resulting in increased cutaneous microflora burden. Toward the end of the luteal phase, a decline in progesterone can be observed, which is known to block androgen receptors (ARs) and inhibit the action of circulating androgens, thereby increasing AR activation (Raghunath et al., 2015).

In addition, during menstruation, progesterone and estrogen decline below basal testosterone levels, creating a relative increase in testosterone that may exacerbate androgen-dependent dermatoses. The activation of ARs by testosterone may also result in increased sebum production creating a favorable extracellular environment for Propionibacterium acnes and thus contributing to hormonal acne flares (Geller et al., 2014). Although this proposed theory is controversial because the exact mechanism of menstrual-related acne is currently unknown, it highlights an underlying association between the menstrual cycle and certain dermatoses.

While estrogen receptors (ERs) are widespread in the epidermis and dermis, progesterone receptors (PRs) are sparse (Farage et al., 2009). ER-β is highly expressed in basal keratinocytes, sebocytes, and eccrine sweat glands; ER-α is expressed in sebocytes. PRs are located in keratinocyte and sebocyte nuclei. ARs are localized to keratinocytes, 10% of dermal fibroblasts, sebaceous gland basal cells, sebocytes, and the dermal cell layer of hair follicles. Very few eccrine sweat glands express ARs (Pelletier and Ren, 2004).

Cyclic estrogen and progesterone production activate skin receptors and maintain skin homeostasis, including components of barrier function such as epidermal thickness, hydration, lipid and sebum production, and fat deposition. Hormones affect dermal collagen content and thus alter skin elasticity and aging (Farage et al., 2009, Shah and Maibach, 2001). Estrogen induces dermal sebaceous glands to produce intracellular versican and fibroblasts to release extracellular hyaluronic acid that increases skin moisture (Farage et al., 2009). Estrogen is also involved in the regulation of ultraviolet (UV)-induced skin damage and pigmentation by inducing intraepidermal melanogenesis, which causes transient patchy hyperpigmentation around the eyelids prior to menstruation. The effect of progesterone on skin physiology is not well known (Farage et al., 2009, Hermanns-Le et al. 2013, Stephens, 1997).

Sex hormones also influence the cutaneous immune milieu, which may play an important role in the cyclical exacerbations of catamenial dermatoses. Cytotoxic and helper T-cells, as well as macrophages and monocytes, express ER-α and -β. The activation of estrogen pathways is associated with toll-like receptors (TLRs) expression. TLR upregulation lowers the innate immune threshold and enhances immune response when estrogen levels are elevated, which may explain why certain autoimmune conditions fluctuate in severity during menstruation. Membrane-bound PR-α has been detected in the outer cellular membrane of CD8+ T-cells during the luteal phase, but not CD4+ lymphocytes (Dosiou et al., 2008, Young et al., 2014).

Sex hormone receptors in the skin play a role in homeostasis. Increases in relative proportions of hormones may lead to skin pathology. This systematic review provides an overview of the current literature on catamenial dermatoses.

Methods

The search terms “menses” and “skin” were used in July 2018 to conduct a systematic review in the PubMed database, including autoimmune progesterone dermatitis, autoimmune estrogen dermatitis, allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), atopic dermatitis (AD), Behcet's syndrome, bullous pemphigoid (BP), hereditary angioedema (HA) impetigo herpetiformis (IH), keratosis follicularis (KF), psoriasis, pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). After identification of relevant dermatoses, each disease was individually searched with “menses,” along with [“allergies” and “skin” and “menses”], [“progesterone dermatitis” and “case”], and [“estrogen dermatitis” and “case”].

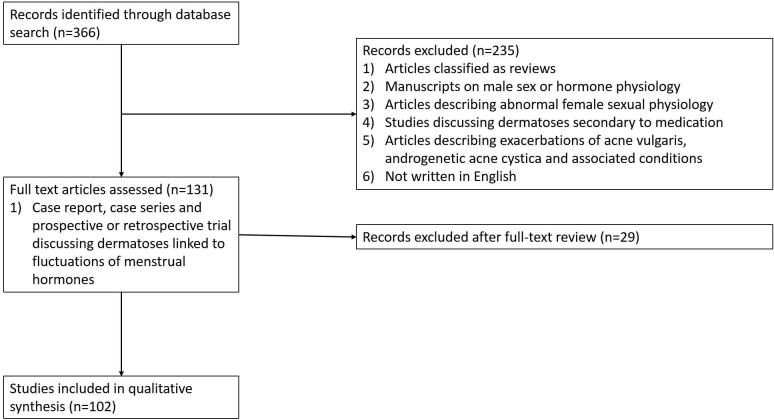

The inclusion criteria were case reports and series, clinical studies, and clinical trials written in English. The exclusion criteria included review articles; manuscripts in a language other than English; articles focusing on male sex or hormonal physiology; abnormal female sexual physiology including dysmenorrhea, endometriosis, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and hormonal physiology of pregnancy; and articles on dermatoses secondary to medications. Studies that reported on exacerbations of catamenial acne vulgaris, androgenetic acne cystica, and associated conditions such as hidradenitis suppurativa were omitted because the correlation between disease and hormonal variation is well established (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram depicting systematic search criteria for this review.

Results

Initially, 366 studies were identified through the PubMed database. Screening of the titles and abstracts excluded 235 studies, with another 29 studies excluded after full-article review. A total of 102 articles (with a total 1269 patients) reported on the cutaneous manifestations of dermatoses that flare with menstruation, including primary sensitivities to female sex hormones (autoimmune progesterone or estrogen dermatitis [AIPD/AIED]) and cutaneous manifestations of inflammatory diseases, such as ACD, AD, Behcet’s syndrome, BP, HA, IH, KF, psoriasis, PG, and SLE.

Autoimmune dermatoses

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis

AIPD, the most common primary catamenial dermatosis, is a reaction to luteal phase progesterone (Herzberg et al., 1995). Hypotheses of AIPD pathogenesis include the development of progesterone autoantibodies to endogenous or exogenous hormone and immune complex deposition. The clinical presentation is similar to inflammatory conditions including AD, urticaria, angioedema, and drug eruptions, making AIPD difficult to diagnose (Wintzen et al., 2004, You et al., 2017).

Sixty-seven case reports and seven case series (n = 110; age range: 13–55 years) were identified. AIPD diagnostic criteria include skin lesions associated with the menstrual cycle, a positive skin or systemic response to an intramuscular or intradermal progesterone challenge, and symptomatic improvement of a rash with inhibition of ovulation (Stranahan et al., 2006, Warin, 2001). The most common symptoms of AIPD include urticaria (n = 50), pruritus (n = 27), angioedema (n = 21), and erythema multiforme (n = 19). Symptoms of AIPD begin 3 to 10 days prior to and resolve 1 to 2 days after menses (Anderson, 1984, Asai et al., 2009, Bandino et al., 2011, Baptist and Baldwin, 2004, Berger, 1969, Bernstein et al., 2011, Bolaji and O'Dwyer, 1992, Camoes et al., 2017, Chawla et al., 2009, Choi et al., 2009, Cocuroccia et al., 2006, Cristaudo et al., 2007, Dedecker et al., 2005, Detrixhe et al., 2017, Domeyer-Klenske et al., 2015, Drayer et al., 2018, Farah and Shbaklu, 1971, Foer et al., 2016, Fournier, 2015, Frieder and Younus, 2016, Garcia-Ortega and Scorza, 2011, George and Badawy, 2012, Georgouras, 1981, Grunnet et al., 2017, Hacinecipoglu et al., 2016, Halevy et al., 2002, Hart, 1977, Herzberg et al., 1995, Hill and Carr, 2013, Honda et al., 2014, Izu et al., 2001, Jenkins et al., 2008, Jones and Gordon, 1969, Kakarla and Zurawin, 2006, Katayama and Nishioka, 1985, Kaygusuz et al., 2014, Lahmam Bennani et al., 2012, Le and Wood, 2011, Lee et al., 1992, Lee et al., 2011, Mbonile, 2016, Medeiros et al., 2010, Moghadam et al., 1998, Mokhtari et al., 2017, Moody and Schatten, 1997, Nasabzadeh et al., 2010, Nemeth et al., 2009, Oskay et al., 2002, Ozmen and Akturk, 2016, Poffet et al., 2011, Prieto-Garcia et al., 2011, Rasi and Khatami, 2004, Rodenas et al., 1998, Salman and Ergun, 2017, Shahar et al., 1997, Snyder and Krishnaswamy, 2003, Stephens et al., 1989, Stone and Downham, 1981, Teelucksingh and Edwards, 1990, Toms-Whittle et al., 2011, Tromovitch and Heggli, 1967, Vasconcelos et al., 2000, Walling and Scupham, 2008, Warin, 2001, Wingate-Saul et al., 2015, Wintzen et al., 2004, Wojnarowska et al., 1985, Yee and Cunliffe, 1994, You et al., 2017). Although rare, autoimmune progesterone anaphylaxis may occur up to 1 month prior to menses (Bemanian et al., 2007).

AIPD therapies decrease inflammation and endogenous progesterone production, including antihistamines, systemic steroids, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, conjugated estrogen, oral contraceptives, tamoxifen, and hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Patients may respond well to any of the therapies listed, but the only modality with complete remission of disease in all treated patients is bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (Table 1; Anderson, 1984, Asai et al., 2009, Bandino et al., 2011, Baptist and Baldwin, 2004, Berger, 1969, Bernstein et al., 2011, Bolaji and O'Dwyer, 1992, Camoes et al., 2017, Chawla et al., 2009, Choi et al., 2009, Cocuroccia et al., 2006, Cristaudo et al., 2007, Dedecker et al., 2005, Detrixhe et al., 2017, Domeyer-Klenske et al., 2015, Drayer et al., 2018, Farah and Shbaklu, 1971, Foer et al., 2016, Fournier, 2015, Frieder and Younus, 2016, Garcia-Ortega and Scorza, 2011, George and Badawy, 2012, Georgouras, 1981, Grunnet et al., 2017, Hacinecipoglu et al., 2016, Halevy et al., 2002, Hart, 1977, Herzberg et al., 1995, Hill and Carr, 2013, Honda et al., 2014, Izu et al., 2001, Jenkins et al., 2008, Jones and Gordon, 1969, Kakarla and Zurawin, 2006, Katayama and Nishioka, 1985, Kaygusuz et al., 2014, Lahmam Bennani et al., 2012, Le and Wood, 2011, Lee et al., 1992, Lee et al., 2011, Mbonile, 2016, Medeiros et al., 2010, Moghadam et al., 1998, Mokhtari et al., 2017, Moody and Schatten, 1997, Nasabzadeh et al., 2010, Nemeth et al., 2009, Oskay et al., 2002, Ozmen and Akturk, 2016, Poffet et al., 2011, Prieto-Garcia et al., 2011, Rasi and Khatami, 2004, Rodenas et al., 1998, Salman and Ergun, 2017, Shahar et al., 1997, Snyder and Krishnaswamy, 2003, Stephens et al., 1989, Stone and Downham, 1981, Teelucksingh and Edwards, 1990, Toms-Whittle et al., 2011, Tromovitch and Heggli, 1967, Vasconcelos et al., 2000, Walling and Scupham, 2008, Warin, 2001, Wingate-Saul et al., 2015, Wintzen et al., 2004, Wojnarowska et al., 1985, Yee and Cunliffe, 1994, You et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Summary of reported cases of AIPD and AIED.

| AIPD | AIED | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age range (years) | 13–55 | Age range (years) | 21–47 |

| Manifestation | n | Manifestation | n |

| Urticaria | 50 | Pruritus | 10 |

| Pruritus | 27 | Urticaria | 9 |

| Angioedema | 21 | Atopic dermatitis | 3 |

| Erythema multiforme | 19 | Anasarca/edema | 2 |

| Vesiculobullous eruptions | 11 | Erythema annulare centrifugum | 1 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 8 | Erythema multiforme | 1 |

| Papules | 5 | Telangiectasia | 1 |

| Purpura | 4 | Hyperpigmentation | 1 |

| Anasarca/edema | 4 | Papulovesicular Eruption | 1 |

| Fixed drug eruption | 3 | ||

| Steven Johnson syndrome | 3 | ||

| Stomatitis | 3 | ||

| Erythema annulare centrifugum | 2 | ||

| Treatment | Treatment | n | |

| Progesterone desensitization | 18 | Tamoxifen | 20 |

| Oophorectomy/hysterectomy | 14 | Leuprolide (GnRH analog) | 2 |

| Combined oral contraceptive | 12 | Oophorectomy | 1 |

| Estrogen contraceptive | 10 | Topical steroid agents | 1 |

| Steroids (oral or topical) | 10 | None/lost to follow-up | 2 |

| GnRH analog | 10 | ||

| Antihistamine | 6 | ||

| Tamoxifen | 5 | ||

| None/lost to follow-up | 26 | ||

AIED, autoimmune estrogen dermatitis; AIPD, autoimmune progesterone dermatitis; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

Autoimmune estrogen dermatitis

Similar to AIPD, AIED is a cyclical cutaneous eruption caused by estrogen sensitivity during the menstrual follicular phase. Eight case reports and two case series (n = 26; age range: 21–47 years) were found. Clinically, AIED is similar to AIPD with pruritus (n = 10) or urticaria (n = 9) as the most common presenting cutaneous manifestations (Table 1; Bourgeault et al., 2017, Elcin et al., 2017, Kim et al., 1997, Kumar and Georgouras, 1999, Leylek et al., 1997, Murano and Koyano, 2003, Perdue et al., 2014, Shelley et al., 1995, Yoon et al., 2005, Yotsumoto et al., 2003). Along with AIPD, the major diagnostic clue for AIED is premenstrual worsening of skin lesions.

To differentiate AIED from AIPD, intradermal skin tests identifying estrogen sensitivity and the absence of progesterone sensitivity must be completed (Shelley et al., 1995). Therapy for AIED targets estrogen and its receptors. Review of the literature revealed that 77% of cases demonstrate a complete resolution with tamoxifen.

Exacerbations of chronic inflammatory dermatoses

Psoriasis

Three relevant studies (n = 48) were found (Ceovic et al., 2013, Mowad et al., 1998, Murase et al., 2005). Although the exact pathogenesis of psoriasis is unknown, imbalanced T-helper (Th) cells (Th1 and Th17) are believed to affect inflammation. Disease distribution is bimodal in women, with peaks during late adolescence/early 20s and the perimenopausal period; disease severity may worsen with the menstrual cycle (Stevens et al., 1993). Of note, psoriasis often improves, and may resolve, during pregnancy only to reappear after delivery, suggesting that increased estrogen and progesterone may be associated with decreased disease severity (Ceovic et al., 2013, Mowad et al., 1998). A case-control study comparing 47 pregnant with 27 nonpregnant, menstruating women with psoriasis demonstrated that increased estradiol, estriol, and the estrogen:progesterone ratio were correlated with improvement in psoriasis-affected body surface area (Murase et al., 2005).

Behcet’s syndrome

Behcet’s syndrome is characterized by uveitis and recurring ulcers of the mouth and genitals. Multiple studies report disease flare associated with menstruation. Two case reports and two case series (n = 229) were found (Bang et al., 1997, Guzelant et al., 2017, Hewitt, 1971, Oh et al., 2009). In a study of 27 postpartum women, nine experienced exacerbations of their disease related to menstruation, with the hypothesis that flares were related to increased progesterone (Bang et al., 1997).

More recently, a survey study of premenopausal women with Behcet’s syndrome (n = 200) reported that 68% of women experienced exacerbation of at least one skin or mucosal lesion during menses (Guzelant et al., 2017). Successful treatment of Behcet’s syndrome with oral contraceptives further supports the hypothesis that flares are associated with endogenous progesterone levels (Hewitt, 1971, Oh et al., 2009).

Eczematous dermatoses

Although dermatitis may present as part of AIPD or AIED, AD severity may also cycle with menstruation. In one cohort study (n = 286), 47% of patients reported worsening clinical symptoms 1 week prior to menstruation (Kiriyama et al., 2003). One case report described ACD exacerbated by menstruation in a 41-year-old woman. The patient presented with a 2-year history of cyclic, self-healing skin eruptions clinically described as multiple, symmetrical, erythematous, nonpruritic papules on the upper trunk, neck, and arms, associated with abdominal distention and cramps. Symptoms appeared 3 to 7 days before menses and improved with menstruation onset. The patient had a copper-containing intrauterine device placed 12 years prior, and patch test results were positive for copper sulfate. After the copper intrauterine device was removed, the lesions resolved (Pujol et al., 1998).

Hereditary angioedema

HA is characterized by recurrent swelling of the face, limbs, intestinal tract, and airway. In one case series, a mother and daughter with HA experienced worsening edema and erythema of the chest and back during the menstrual luteal phase. At the age of 35 years, the mother was considered the first reported case of premenstrual HA exacerbation. The daughter demonstrated worsening symptoms after taking estrogen-containing oral contraceptives (Yip and Cunliffe, 1992).

Bullous pemphigoid

BP often afflicts elderly patients, making reports of disease fluctuation due to sex hormone changes rare. One case described a 19-year-old woman who was diagnosed with BP as a young teenager, and experienced extensive disease flare-ups after her first menses (Mori et al., 1994). Endogenous estrogens prolong the life of antibody-producing B-cells in murine models; thus, it can be hypothesized that increased estrogen may exacerbate this autoimmune disease (Peeva et al., 2005).

Impetigo herpetiformis

A single case of IH in a 26-year-old post-partum woman describes worsening symptoms prior to each menses for 7 years. Symptoms occurred 2 to 3 days before menstruation and would resolve after 7 days. The patient was unsuccessfully treated with oral cyclosporine, and the medication was discontinued. After 7 years, the IH exacerbations spontaneously resolved, with the hypothesis that skin estrogen receptors were depleted because of increasing age (Chaidemenos et al., 2005).

Keratosis follicularis (Darier disease)

KF presents with hyperkeratotic, greasy papules of seborrheic areas, mucosal lesions, nail bed changes, and palmar pits (Espy et al., 1976). Women experience increased symptom severity compared to men, and symptoms may cyclically worsen with menses. One case series described eight premenopausal women who developed KF during menarche, which flared with menstruation. Three patients treated with estrogen-dominant oral contraceptives demonstrated improvement of symptoms, suggesting a connection between estrogen and KF flares (Espy et al., 1976).

Pyoderma gangrenosum

One case described a 34-year-old woman with a 6-month history of cyclic PG that worsened 1 week prior to menstruation. The patient’s PG resolved after suppression of menses via oral ethinyl estradiol and drospirenone taken daily for 1 month. This resolution suggests a relationship between female sex hormones and the disease course of PG (Jourabchi et al., 2016).

Lupus erythematosus

Female sex hormones may play a role in aggravating cutaneous symptoms of SLE, discoid lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus, drug-induced lupus, and neonatal lupus. Estrogen has been shown to cause increased TLR expression in macrophages, upregulation of inflammatory pathways, and possible induction of autoimmune disease in predisposed patients. SLE is commonly treated with the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine, which inhibits endosomal TLRs.

This disease favors women of reproductive age, with premenopausal women outnumbering men 9:1; postmenopausal and prepubescent women only outnumber men 2:1 (Young et al., 2014). Only one relevant case study (n = 57) was found, including 32 patients with SLE, 25% of whom reported experiencing cyclic flares; 16% of patients with discoid lupus erythematosus experienced cyclic flares. This study identified elevated estradiol prior to ovulation as the exacerbating factor (Yell and Burge, 1993).

Discussion

The menstrual cycle is characterized by tightly regulated sex hormone fluctuations. Primary dermatoses, as well as exacerbations of chronic cutaneous disorders, may occur in association with these fluctuations. In cases of cyclic worsening of skin lesions, it is important that physicians consider menstrual cycle association (Table 2; DeRosa et al., 2015).

Table 2.

Timing of disease flare during menstrual cycle.

| Disease flare prior to menses | |

|---|---|

| Autoimmune estrogen dermatitis | 14 days prior |

| Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis | 3–10 days prior |

| Eczematous dermatoses | 1 week prior |

| Hereditary angioedema | Unspecified |

| Impetigo herpetiformis | 2–3 days prior |

| Keratosis follicularis | Unspecified |

| Psoriasis | Unspecified |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 1 week prior |

| Systemic lupus erythematous | Unspecified |

| Disease flare during menses | |

| Behcet’s syndrome | |

| Bullous pemphigoid | |

Immune cells and cytokines fluctuate with the menstrual cycle, especially regulatory T-cells (Arruvito et al., 2007). The level and activity of B-lymphocytes may also increase in the periovulatory period due to high estrogen levels (Grimaldi et al., 2002). During this period, estrogen levels are similar to those during pregnancy, preventing B-cell apoptosis and increasing autoreactive cell survival, which may be a possible explanation for cutaneous exacerbations of certain autoimmune diseases (Grimaldi et al., 2002). Estrogen enhances immune system activation via upregulation of TLR3/7/8/9. High estrogen levels may inappropriately lower the threshold of innate immune activation, creating a plausible mechanism for the increased prevalence of autoimmune disease in women (Cheesman et al., 1982, Cunningham and Gilkeson, 2011, Grimaldi et al., 2002, Oertelt-Prigione, 2012, Peeva et al., 2005, Young et al., 2014).

The most common primary catamenial dermatosis is AIPD. The recommended therapy is progesterone desensitization. However, the only treatment modality with complete AIPD remission is surgical removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes. Other rare cases of menstrual cutaneous exacerbations include psoriasis, Bechet’s syndrome, eczematous dermatoses including ACD and AD, BP, HA, and persistent postpartum IH. Estrogen is implicated as a cause of AIED and lupus flares, as well as HA.

Most cutaneous conditions worsen in association with estrogen or progesterone, but KF may improve during periods of increased estrogen levels. The complex interaction between sex hormones and skin, as well as variations among individual diseases, demonstrate that further research is needed to delineate a sex hormone–skin axis. Until the causative mechanisms of catamenial dermatoses are understood, physicians should be aware that menses may cause disease exacerbation and should treat patients with a catamenial-associated flare of their primary or underlying dermatosis accordingly.

The rarity of certain catamenial dermatoses leads to limitations in this systematic review. The literature linking menstruation to ACD, BP, HA, IH, and PG are limited to singular reports. Details of disease flare, such as causative hormones/receptors, are not robustly reported. Further large-scale, cohort studies should be completed for each disease to determine the connection between exacerbation and menstrual cycle to better understand pathophysiology and treatment strategies.

Conclusion

The menstrual cycle and female sex hormones (estrogen and progesterone) contribute to the pathogenesis of a variety of primary and chronic skin conditions through unknown mechanisms. Hypotheses include catamenial hormonal receptor activation, aberrant initiation of the innate immune system, prolongation of antibody production by B-cells, and survival of autoreactive cells. Evidence from the current literature suggests that hormonal fluctuations during menstruation exacerbate a vast range of dermatologic conditions, including autoimmune dermatoses, chronic dermatoses, and cutaneous manifestations of systemic diseases. Further large-scale studies are needed to determine whether estrogen or progesterone plays a large role in cutaneous disease flare and whether hormonal adjuvants are effective treatment modalities.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Study Approval

NA.

Footnotes

No human subjects were included in this study. No animals were used in this study.

References

- Anderson R.H. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Cutis. 1984;33:490–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruvito L., Sanz M., Banham A.H., Fainboim L. Expansion of CD4+CD25+and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle: implications for human reproduction. J Immunol. 2007;178:2572–2578. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai J., Katoh N., Nakano M., Wada M., Kishimoto S. Case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption. J Dermatol. 2009;36:643–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2009.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandino J.P., Thoppil J., Kennedy J.S., Hivnor C.M. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis caused by 17alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate for preterm labor prevention. Cutis. 2011;88:241–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang D., Chun Y.S., Haam I.B., Lee E.S., Lee S. The influence of pregnancy on Behcet's disease. Yonsei Med J. 1997;38:437–443. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1997.38.6.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptist A.P., Baldwin J.L. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in a patient with endometriosis: Case report and review of the literature. Clin Mol Allergy. 2004;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bemanian M.H., Gharagozlou M., Farashahi M.H., Nabavi M., Shirkhoda Z. Autoimmune progesterone anaphylaxis. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;6:97–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger H. Progesterone. Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:117. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1969.01610250123030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein I.L., Bernstein D.I., Lummus Z.L., Bernstein J.A. A case of progesterone-induced anaphylaxis, cyclic urticaria/angioedema, and autoimmune dermatitis. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011;20:643–648. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolaji I.I., O'Dwyer E.M. Post-menopausal cyclic eruptions: autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1992;47:169–171. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(92)90050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeault E., Bujold J., Doucet M.E. A rare case of oestrogen dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21:261–262. doi: 10.1177/1203475416685075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camoes S., Sampaio J., Rocha J., Tiago P., Lopes C. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: case report of an unexpected treatment reaction. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e132–e134. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceovic R., Mance M., Bukvic Mokos Z., Svetec M., Kostovic K., Stulhofer Buzina D. Psoriasis: Female skin changes in various hormonal stages throughout life–puberty, pregnancy, and menopause. Biomed Res Int. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/571912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaidemenos G., Lefaki I., Tsakiri A., Mourellou O. Impetigo herpetiformis: menstrual exacerbations for 7 years postpartum. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:466–469. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla S.V., Quirk C., Sondheimer S.J., James W.D. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:341–342. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2008.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheesman K.L., Gaynor L.V., Chatterton R.T., Jr, Radvany R.M. Identification of a 17-hydroxyprogesterone-binding immunoglobulin in the serum of a woman with periodic rashes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;55:597–599. doi: 10.1210/jcem-55-3-597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi K.W., Lee C.Y., Lee Y.K., Kim Y.H., Kim K.H. The photosensitivity localized in a vitiliginous lesion was associated with the intramuscular injections of synthetic progesterone during an in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:88–91. doi: 10.5021/ad.2009.21.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocuroccia B., Gisondi P., Gubinelli E., Girolomoni G. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2006;22:54–56. doi: 10.1080/09513590500216735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo K., Haig S., Bonner A., Zelenietz C., Pope J. Self-reported flaring varies during the menstrual cycle in systemic lupus erythematosus compared with rheumatoid arthritis and fibromyalgia. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:703–708. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristaudo A., Bordignon V., Palamara F., De Rocco M., Pietravalle M., Picardo M. Progesterone sensitive interferon-gamma producing cells detected by ELISpot assay in autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:439–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M., Gilkeson G. Estrogen receptors in immunity and autoimmunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2011;40:66–73. doi: 10.1007/s12016-010-8203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dedecker F., Graesslin O., Quereux C., Gabriel R., Salmon-Ehr V. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a rare pathology. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2005;123:120–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRosa A., Adams S., Fee E.K. Progressively worsening cyclic rash: diagnosis and approach to care. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2015;115:738–744. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2015.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detrixhe A., Nikkels A.F., Dezfoulian B. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;296:1013–1014. doi: 10.1007/s00404-017-4497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domeyer-Klenske A., Robillard D., Pulvino J., Spratt D. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist use to guide diagnosis and treatment of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:1114–1116. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosiou C., Hamilton A.E., Pang Y., Overgaard M.T., Tulac S., Dong J. Expression of membrane progesterone receptors on human T lymphocytes and Jurkat cells and activation of G-proteins by progesterone. J Endocrinol. 2008;196:67–77. doi: 10.1677/JOE-07-0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drayer S.M., Laufer L.R., Farrell M.E. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis mistaken for Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131:723–726. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elcin G., Gulseren D., Bayraktar M., Gunalp S., Gurgan T. Autoimmune estrogen dermatitis in an infertile female. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2017;36:195–198. doi: 10.1080/15569527.2016.1245197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espy P.D., Stone S., Jolly H.W., Jr. Hormonal dependency in Darier disease. Cutis. 1976;17:315–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farage M.A., Neill S., MacLean A.B. Physiological changes associated with the menstrual cycle: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2009;64:58–72. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3181932a37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farah F.S., Shbaklu Z. Autoimmune progesterone urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1971;48:257–261. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(71)90025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foer D., Buchheit K.M., Gargiulo A.R., Lynch D.M., Castells M., Wickner P.G. Progestogen hypersensitivity in 24 cases: diagnosis, management, and proposed renaming and classification. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016;4:723–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fournier J.B. Resolution of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis after treatment with oral contraceptives. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:319–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieder J., Younus M. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis with delayed intradermal skin reaction: a case report. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:438–439. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ortega P., Scorza E. Progesterone autoimmune dermatitis with positive autologous serum skin test result. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:495–498. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318206cb2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller L., Rosen J., Frankel A., Goldenberg G. Perimenstrual flare of adult acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:30–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George R., Badawy S.Z. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a case report. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/757854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgouras K. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 1981;22:109–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1981.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi C.M., Cleary J., Dagtas A.S., Moussai D., Diamond B. Estrogen alters thresholds for B cell apoptosis and activation. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1625–1633. doi: 10.1172/JCI14873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunnet K.M., Powell K.S., Miller I.A., Davis L.S. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis manifesting as mucosal erythema multiforme in the setting of HIV infection. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:22–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzelant G., Ozguler Y., Esatoglu S.N., Karatemiz G., Ozdogan H., Yurdakul S. Exacerbation of Behcet’s syndrome and familial Mediterranean fever with menstruation. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017;35(Suppl 108):95–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacinecipoglu F., Benar H., Gonul M., Okcu Heper A. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis characterized by grouped small vesicles. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016;41:681–682. doi: 10.1111/ced.12840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halevy S., Cohen A.D., Lunenfeld E., Grossman N. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis manifested as erythema annulare centrifugum: Confirmation of progesterone sensitivity by in vitro interferon-gamma release. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:311–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart R. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1977;113:426–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanns-Le T., Hermanns J.F., Lesuisse M., Pierard G.E. Cyclic catamenial dermatoses. Biomed Res Int. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/156459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg A.J., Strohmeyer C.R., Cirillo-Hyland V.A. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:333–338. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt A.B. Behcet’s disease. Alleviation of buccal and genital ulceration by an oral contraceptive agent. Br J Vener Dis. 1971;47:52–53. doi: 10.1136/sti.47.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J.L., Carr T.F. Iatrogenic autoimmune progesterone dermatitis treated with a novel intramuscular progesterone desensitization protocol. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1:537–538. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honda T., Kabashima K., Fujii Y., Katoh M., Miyachi Y. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis that changed its clinical manifestation from anaphylaxis to fixed drug eruption-like erythema. J Dermatol. 2014;41:447–448. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.12473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izu K., Yamamoto O., Yamaguchi J., Ohta T., Asahi M. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. J UOEH. 2001;23:431–436. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.23.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins J., Geng A., Robinson-Bostom L. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis associated with infertility treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:353–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.10.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones W.N., Gordon V.H. Auto-immune progesterone eczema. An endogenous progesterone hypersensitivity. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:57–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourabchi N., Rhee S.M., Lazarus G.S. Premenstrual flares of pyoderma gangrenosum controlled with use of a combined oral contraceptive and antiandrogen (ethinyl estradiol/drospirenone) Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:1096–1097. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakarla N., Zurawin R.K. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis in an adolescent female. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006;19:125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama I., Nishioka K. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis with persistent amenorrhoea. Br J Dermatol. 1985;112:487–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaygusuz I., Gumus I.I., Sarifakioglu E., Eser A., Bozkurt B., Kafali H. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53:420–422. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K.H., Yoon T.J., Oh C.W., Kim T.H. A case of estrogen dermatitis. J Dermatol. 1997;24:332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1997.tb02800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiriyama K., Sugiura H., Uehara M. Premenstrual deterioration of skin symptoms in female patients with atopic dermatitis. Dermatology. 2003;206:110–112. doi: 10.1159/000068463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Georgouras K.E. Oestrogen dermatitis. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:96–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.1999.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahmam Bennani Z., El Fekih N., Baccouche D., Khaled A., Zaglaoui F., Fazaa B. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2012;139:832–835. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latman N.S. Relation of menstrual cycle phase to symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med. 1983;74:957–960. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)90789-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le K., Wood G. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis diagnosed by progesterone pessary. Australas J Dermatol. 2011;52:139–141. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2011.00753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.W., Yoon K.B., Yi J.U., Cho S.H. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. J Dermatol. 1992;19:629–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1992.tb03743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.K., Lee W.Y., Yong S.J., Shin K.C., Lee S.N., Lee S.J. A case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis misdiagnosed as allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2011;3:141–144. doi: 10.4168/aair.2011.3.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leylek O.A., Unlü S., Oztürkcan S., Cetin A., Sahin M., Yildiz E. Estrogen dermatitis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;72:97–103. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(96)02657-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mbonile L. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: Case report with history of urticaria, petechiae and palpable pinpoint purpura triggered by medical abortion. S Afr Med J. 2016;106:48–50. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i4.9896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medeiros S., Rodrigues-Alves R., Costa M., Afonso A., Rodrigues A., Cardoso J. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: treatment with oophorectomy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:e12–e13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam B.K., Hersini S., Barker B.F. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis and stomatitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:537–541. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtari R., Sepaskhah M., Aslani F.S., Dastgheib L. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting as fixed drug eruption: a case report. Dermatol Online J. 2017:23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody B.R., Schatten S. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: onset in a women without previous exogenous progesterone exposure. South Med J. 1997;90:845–846. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199708000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori O., Hachisuka H., Kusuhara M., Sasai Y., Fujiwara S. Bullous pemphigoid in a 19-year-old woman. A case with unusual target antigens. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:241–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb02909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowad C.M., Margolis D.J., Halpern A.C., Suri B., Synnestvedt M., Guzzo C.A. Hormonal influences on women with psoriasis. Cutis. 1998;61:257–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murano K., Koyano T. Estrogen dermatitis that appeared twice in each menstrual period. J Dermatol. 2003;30:719–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2003.tb00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murase J.E., Chan K.K., Garite T.J., Cooper D.M., Weinstein G.D. Hormonal effect on psoriasis in pregnancy and post partum. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:601–606. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.5.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasabzadeh T.J., Stefanato C.M., Doole J.E., Radfar A., Bhawan J., Venna S. Recurrent erythema multiforme triggered by progesterone sensitivity. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:1164–1167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth H., Kovacs E., Godeny S., Simics E., Pfliegler G. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis diagnosed by intravaginal progesterone provocation in a hysterectomised woman. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25:410–412. doi: 10.1080/09513590902770164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertelt-Prigione S. Immunology and the menstrual cycle. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11:A486–A492. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh S.H., Kwon J.Y., Lee J.H., Han E.C., Bang D. Behcet's disease: Remission of patient symptoms after oral contraceptive therapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e88–e90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2008.03201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oskay T., Kutluay L., Kaptanoglu A., Karabacak O. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:589–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozmen I., Akturk E. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting with purpura. Cutis. 2016;98:E12–E13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeva E., Venkatesh J., Diamond B. Tamoxifen blocks estrogen-induced B cell maturation but not survival. J Immunol. 2005;175:1415–1423. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier G., Ren L. Localization of sex steroid receptors in human skin. Histol Histopathol. 2004;19:629–636. doi: 10.14670/HH-19.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdue N., Ezra N., Mousdicas N. Estrogen dermatitis presenting as gyrate erythema treated with leuprolide. Dermatitis. 2014;25:277–278. doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poffet F., Abraham S., Taramarcaz P., Fontao L., Borradori L. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: potential role of cutaneous angiogenin expression? Dermatology. 2011;223:32–35. doi: 10.1159/000329427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto-Garcia A., Sloane D.E., Gargiulo A.R., Feldweg A.M., Castells M. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: clinical presentation and management with progesterone desensitization for successful in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(1121):e1129–e1131. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol R.M., Randazzo L., Miralles J., Alomar A. Perimenstrual dermatitis secondary to a copper-containing intrauterine contraceptive device. Contact Dermatitis. 1998;38:288. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1998.tb05751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghunath R.S., Venables Z.C., Millington G.W. The menstrual cycle and the skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:111–115. doi: 10.1111/ced.12588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasi A., Khatami A. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:588–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodenas J.M., Herranz M.T., Tercedor J. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: treatment with oophorectomy. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:508–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salman A., Ergun T. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis mimicking fixed drug eruption. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017;15:219–220. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah M.G., Maibach H.I. Estrogen and skin. An overview. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2001;2:143–150. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200102030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar E., Bergman R., Pollack S. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: Effective prophylactic treatment with danazol. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:708–711. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley W.B., Shelley E.D., Talanin N.Y., Santoso-Pham J. Estrogen dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:25–31. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J.L., Krishnaswamy G. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis and its manifestation as anaphylaxis: a case report and literature review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;90:469–477. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61838-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens C.J. Perimenstrual eruptions. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:31–34. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(96)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens C.J., Wojnarowska F.T., Wilkinson J.D. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis responding to tamoxifen. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:135–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb01410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens H.P., Ostlere L.S., Black C.M., Jacobs H.S., Rustin M.H. Cyclical psoriatic arthritis responding to anti-oestrogen therapy. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:458–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone J., Downham T. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:50–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1981.tb05289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stranahan D., Rausch D., Deng A., Gaspari A. The role of intradermal skin testing and patch testing in the diagnosis of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2006;17:39–42. doi: 10.2310/6620.2006.05045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teelucksingh S., Edwards C.R. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. J Intern Med. 1990;227:143–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1990.tb00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toms-Whittle L.M., John L.H., Griffiths D.J., Buckley D.A. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis: a diagnosis easily missed. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:378–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tromovitch T.A., Heggli W.F. Autoimmune progesterone urticaria. Calif Med. 1967;106:211–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos C., Xavier P., Vieira A.P., Martinho M., Rodrigues J., Bodas A. Autoimmune progesterone urticaria. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2000;14:245–247. doi: 10.3109/09513590009167688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walling H.W., Scupham R.K. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Case report with histologic overlap of erythema multiforme and urticaria. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:380–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warin A.P. Case 2. Diagnosis: erythema multiforme as a presentation of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:107–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingate-Saul L., Rymer J., Greaves M.W. Chronic urticaria due to autoreactivity to progesterone. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40:644–646. doi: 10.1111/ced.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintzen M., Goor-van Egmond M.B., Noz K.C. Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis presenting with purpura and petechiae. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2004.01516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojnarowska F., Greaves M.W., Peachey R.D., Drury P.L., Besser G.M. Progesterone-induced erythema multiforme. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:407–408. doi: 10.1177/014107688507800512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee K.C., Cunliffe W.J. Progesterone-induced urticaria: response to buserelin. Br J Dermatol. 1994;130:121–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb06897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yell J.A., Burge S.M. The effect of hormonal changes on cutaneous disease in lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip J., Cunliffe W.J. Hormonally exacerbated hereditary angioedema. Australas J Dermatol. 1992;33:35–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1992.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon T.Y., Kim Y.G., Kim M.K. Estrogen dermatitis responding to leuprolide acetate. J Dermatol. 2005;32:405–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2005.tb00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yotsumoto S., Shimomai K., Hashiguchi T., Uchimiya H., Usuki K., Nishi M. Estrogen dermatitis: a dendritic-cell-mediated allergic condition. Dermatology. 2003;207:265–268. doi: 10.1159/000073088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You H.R., Yun S.J., Kim S.J., Lee S.C., Won Y.H., Lee J.B. Three cases of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29:479–482. doi: 10.5021/ad.2017.29.4.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Young N.A., Wu L.C., Burd C.J., Friedman A.K., Kaffenberger B.H., Rajaram M.V. Estrogen modulation of endosome-associated toll-like receptor 8: An IFNalpha-independent mechanism of sex-bias in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Immunol. 2014;151:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]