Abstract

Cutaneous endometriosis is a disorder that primarily affects women of reproductive age. The disorder is most commonly associated with cyclical pain during menses, but it can be difficult to diagnose in the absence of these symptoms and requires biopsy testing for a definitive diagnosis. We report on a case of a 41-year-old patient undergoing hormonal therapy for infertility who presented with a painful firm subcutaneous nodule in the umbilicus. She was ultimately diagnosed with cutaneous endometriosis and underwent surgical excision. In this report, we discuss the differential diagnosis and comment on treatment options, including surgical excision with wide margins or treatment with hormonal agents, such as danazol or leuprolide. Finally, we discuss whether patients with cutaneous endometriosis should receive an additional evaluation for pelvic endometriosis.

Keywords: Cutaneous endometriosis, endometriosis, hormone therapy

Introduction

Endometriosis represents the presence of non-neoplastic endometrial tissue outside the uterus. The disease is relatively common and typically affects the ovaries and presents with deep pelvic pain, dyspareunia, and dysmenorrhea. Cutaneous endometriosis is relatively uncommon and occurs when endometrial glands and stroma reside in the skin. Cutaneous endometriosis can be divided into primary and secondary endometriosis. The pathogenesis for primary cutaneous endometriosis remains unclear, but secondary cutaneous endometriosis is believed to occur due to seeding after abdominal or pelvic surgery.

Because the condition is rare and can mimic presentations of other diseases, such as keloid or dermatofibroma, cutaneous endometriosis can be difficult to diagnose. Punch biopsy can be performed to obtain tissue for histopathologic testing, but physicians must take care to obtain abdominal ultrasound if there is potential for uterocutaneous fistula. Once the diagnosis has been established, treatment options include hormonal agents and surgical excision with wide margins.

Case report

A 41-year-old woman presented to our department with a 5-month history of a painful firm subcutaneous nodule in the umbilicus. She experienced flares of pain with her menstrual cycle. Her medical history was notable for a missed abortion, for which she underwent dilation and curettage in 2009. She also underwent laparoscopic left salpingectomy for a ruptured ectopic pregnancy in 2013. At the time of presentation, the patient was undergoing fertility treatments, including subcutaneous injections of follitropin beta and choriogonadotropin alfa.

On physical examination, a firm subcutaneous nodule was noted on the umbilicus with slight erythema of the overlying skin. A diagnosis of cutaneous endometriosis was suspected given the patient’s history of laparoscopic salpingectomy and flares of pain with menstrual periods. An ultrasound was performed with reproductive endocrinology to rule out fistula. Once completed, a punch biopsy of the nodule was performed (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). The biopsy results showed endometrial glands with encompassing fibrotic stroma, consistent with cutaneous endometriosis. The site was most likely seeded during the laparoscopic port site entry during her left salpingectomy in 2013.

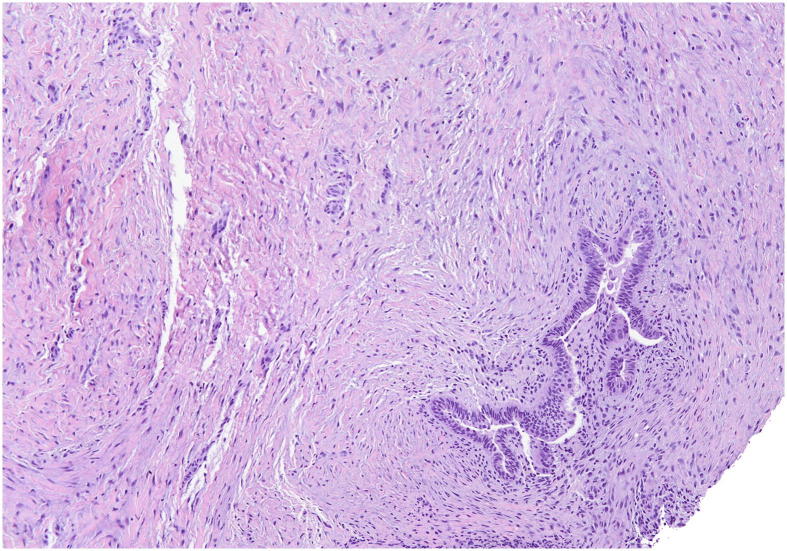

Fig. 1.

Endometrial glands surrounded by scant hypercellular stroma (right), consistent with a diagnosis of endometriosis. The remainder of the tissue is fibrotic and represents a chronic reactive change induced by the adjacent cycling ectopic tissue.

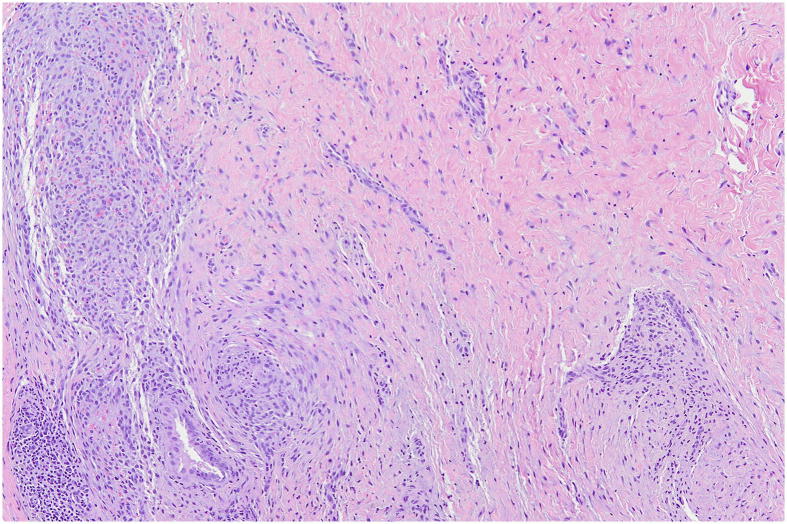

Fig. 2.

Endometrial gland (left) with plump stromal cells and extravasated erythrocytes prominently flanking the gland. Hemorrhagic stroma in the skin evokes secondary fibrosis, which explains the prominent hemorrhagic scarring to the right of the frame.

The patient was counseled with regard to the etiology of the disease and given treatment options of hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide versus surgical excision. Because the patient was undergoing fertility treatment at the time, she declined hormonal therapy. Her obstetrics and gynecology team was informed, and ultimately a referral was placed to the general surgery department for excision of the nodule.

Discussion

Cutaneous endometriosis is a disorder that primarily affects women of reproductive age and classically presents as a firm subcutaneous papule or nodule that averages 2 cm in diameter (Loh et al., 2017). Its color can range from blue or violaceous to brown or skin-colored. Patients frequently experience cyclical pain, swelling, and even bleeding that corresponds with their menstrual cycle (Victory et al., 2007). A diagnosis of cutaneous endometriosis can be made once the presence of endometrial glands and stroma in the skin is established. Notably, an ultrasound should be completed prior to performing a punch biopsy of the lesion to rule out the presence of uterocutaneous fistula.

The skin is an uncommon location for endometriosis, and cutaneous endometriosis cases comprise < 1% of all cases in large series (Victory et al., 2007). One review demonstrated that only 109 cases of cutaneous endometriosis had been described in the literature up to that point in time (Lopez-Soto et al., 2018). Cutaneous endometriosis is subdivided into two categories depending on patients’ surgical history. Primary cutaneous endometriosis refers to cases in which the endometriosis develops spontaneously without any history of local surgery. It is the less common of the two (only 30% of patients present without a surgical history that could explain their cutaneous manifestations; Victory et al., 2007). Secondary cutaneous endometriosis, also called scar endometriosis, is associated with prior abdominal or pelvic surgery (Loh et al., 2017).

Our patient was diagnosed with cutaneous endometriosis based on the cyclical nature of her pain and the diagnostic dermatopathology. Identifying the patient’s surgical history was crucial to subclassifying our patient’s involvement as most likely being secondary in nature.

As with our patient, the most common location for both primary and secondary cutaneous endometriosis is the umbilicus. Umbilical cutaneous endometriosis comprises 30% to 40% of all cutaneous endometriosis cases, but other locations such as the groin, arm, episiotomy wounds, appendectomy scars, and cesarean scars have also been described (Victory et al., 2007).

Many theories have been proposed with regard to the pathogenesis of primary and secondary cutaneous endometriosis. Secondary cutaneous endometriosis is perhaps easier to conceptualize, and the prevailing hypothesis remains that endometrial cells dislodged during surgery seed the wound within and adjacent to the incision sites. In cases of primary cutaneous endometriosis, some postulate that seeding occurs hematogenously or via lymphatics (Victory et al., 2007). In cases of primary cutaneous endometriosis of the umbilicus, some have postulated that the pathogenesis is similar to that of secondary cutaneous endometriosis, with the umbilicus acting as a physiologic scar. A third theory (i.e., metaplastic theory) has offered an explanation for both primary and secondary cutaneous endometriosis and states that cutaneous endometriosis is the result of primitive pluripotent mesenchymal cells undergoing specialized differentiation and metaplasia into endometrial tissue.

The differential diagnosis of umbilical lesions with similar presentation includes keloid, dermatofibroma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and cutaneous metastasis of cancer (e.g., Sister Mary Joseph nodule). Distinguishing between these lesions can be challenging, particularly when patients do not endorse a history of cyclical pain that corresponds with menses.

Adult patients with a keloid typically present with a history of keloid or hypertrophic scars elsewhere on the body. Keloids appear as well-circumscribed pink-to-purple, firm, smooth nodules or plaques with regular or irregular borders. These can develop at umbilical surgical scars, but keloids favor locations with increased tension, such as the shoulder or arms. Sometimes, patients with cutaneous endometriosis will present having already received intralesional corticosteroids for a misdiagnosis of keloid scar (Loh et al., 2017). Intralesional corticosteroids are ineffective to treat cutaneous endometriosis.

Dermatofibromas are benign fibrohistiocytic tumors that present as asymptomatic firm masses that dimple when compressed laterally due to tethering of the epidermis to the underlying nodule (i.e., dimple sign). Dimpling is not considered specific to dermatofibromas but has not been described in cutaneous endometriosis in the literature.

Cutaneous endometriosis can also mimic malignancy. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, a locally aggressive but low-grade soft tissue sarcoma, classically presents in early stages as an asymptomatic, indurated plaque that slowly enlarges. In later stages, the tumor can become raised, firm, and nodular, and telangiectasia may be noted in the surrounding skin. The presence of nodules signifies that the growth has become accelerated, and often nodular growth is associated with ulceration or bleeding, which does not classically occur in cutaneous endometriosis. Ultimately, this condition can only be definitively differentiated from cutaneous endometriosis by biopsy.

Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule, a palpable nodule that protrudes from the umbilicus and represents malignant, metastatic cancer, typically presents with pain, change in bowel habits, or anemia due to underlying abdominal or pelvic cancer. Because gastrointestinal malignancy, particularly that of the ascending colon, can initially have an occult presentation, this diagnosis should be considered even in the absence of obstructive symptoms.

Once a diagnosis of either primary or secondary cutaneous endometriosis is established, the definitive treatment is surgical excision with wide margins, which was the treatment option selected by the patient in this case. The prognosis of cutaneous endometriosis is generally considered favorable. Lopez-Soto et al. (2018) studied 33 women with cutaneous endometriosis; 31 of the women had a surgical history that suggested secondary cutaneous endometriosis. The majority of these women (90%) received surgical excision. Overall, cutaneous endometriosis recurred in 3 women (9%), suggesting surgical excision is a reasonable management option.

The perioperative management of patients may vary. Some suggest performing surgery at the end of the menstrual cycle when lesions are as small as possible, but there is no data to support this practice. Others have recommended either preoperative or postoperative hormonal agents. Preoperatively, the goal of hormonal therapy is to address patients’ discomfort and shrink lesions to a smaller size to facilitate complete removal during surgery. Postoperatively, the goal is to prevent recurrence. Currently, available data do not comment on the best practices for the perioperative management of cutaneous endometriosis.

Another option for patients who do not wish to undergo surgery is treatment with hormonal agents alone, such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists or danazol. These agents work by preventing cyclical proliferation of the endometrial tissue. The primary drawback to medical therapy is the potential for recurrence; ectopic endometrial tissue may resume proliferation once medications are discontinued (Loh et al., 2017). In one case series, Drs. Robert Purvis and Steven Tyring (1994) describe two cases in which medical management was attempted, one with danazol and the other with leuprolide. In both cases, hormonal therapy was able to relieve associated pain, and in one case the nodule diminished in size by approximately 50%. However, the patient treated with monthly injections of subcutaneous leuprolide experienced return of her pain between her second and third treatment cycles. Both patients opted for surgical excision of their lesions within 1 year due to the unfavorable side effects of the hormonal therapies (Purvis and Tyring, 1994). Although surgical excision with wide margins is the gold standard for therapy, if the decision is made to opt for hormonal therapy, surveillance with histopathology should be considered due to case reports noting instances of malignant transformation (Cameron et al., 2017).

The final question for those treating patients with cutaneous endometriosis is whether there is an association between cutaneous and pelvic endometriosis that warrants gynecologic workup for patients presenting with cutaneous disease. Vellido-Cotelo et al. (2015) performed a retrospective case study in which they examined the medical records of 17 patients with scar endometriosis and found that only two (14%) had associated pelvic endometriosis. Although the number of patients studied was quite low, the study authors stated that this 14% fell within the 8% to 15% range that represents the overall incidence of pelvic endometriosis in the general population. Ultimately, patients should be referred to the obstetrics and gynecology department if they describe classic symptoms, including pain with menses, dyspareunia, and infertility, and wish to explore diagnostic and therapeutic options.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Study Approval

NA.

References

- Cameron M., Westwell S., Subramanian A., Ramesar K., Howlett D. Postmenopausal cutaneous endometriosis: Mimicking breast metastasis. Breast J. 2017;23(3):356–358. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loh S.H., Lew B.L., Sim W.Y. Primary cutaneous endometriosis of umbilicus. Ann Dermatol. 2017;29(5):621–625. doi: 10.5021/ad.2017.29.5.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Soto A., Sanchez-Zapata M.I., Martinez-Cendan J.P., Ortiz Reina S., Bernal Mañas C.M., Remezal Solano M. Cutaneous endometriosis: Presentation of 33 cases and literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;221:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purvis R.S., Tyring S.K. Cutaneous and subcutaneous endometriosis. Surgical and hormonal therapy. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20(10):693–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1994.tb00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellido-Cotelo R., Muñoz-González J.L., Oliver-Pérez M.R., de la Hera-Lázaro C., Almansa-González C., Pérez-Sagaseta C. Endometriosis node in gynaecologic scars: A study of 17 patients and the diagnostic considerations in clinical experience in tertiary care center. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:13. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0170-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victory R., Diamond M.P., Johns D.A. Villar's nodule: A case report and systematic literature review of endometriosis externa of the umbilicus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]