Abstract

Background

Pigmentary disorders are common in patients with skin of color and one of the top five most common dermatologic diagnoses in individuals of African descent. Little is known about the spectrum of pigmentary disorders in South Africa’s second largest province, KwaZulu Natal.

Objective

This study aimed to determine the profile of pigmentary disorders in patients at five outpatient public hospital skin clinics in Durban, South Africa.

Methods

We collected data related to age, sex, ethnicity, and skin dyspigmentation diagnosis in a cross-sectional descriptive study of all dermatology patients at five public hospitals in Durban, South Africa between January 1 and March 31, 2015. The diagnosis was made on the basis of clinical grounds, supported by relevant laboratory investigations or histopathology where necessary. Only data relating to patients’ first visit were recorded and captured using a Microsoft Excel 2007 spreadsheet.

Results

A total of 304 patients, the majority of whom were African women (n = 230; 75.8%), were included in the study. The three most common pigmentary diagnoses included vitiligo, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and melasma.

Conclusion

Dyschromias are the third most common dermatologic diagnosis in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa. The most common subtypes of pigmentary disorders include (in order of frequency) vitiligo, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, and melasma.

Keywords: African, black, dyschromia, dyspigmentation, ethnic skin, Indian, pigmentation, skin of color, South Africa

Introduction

Disorders of pigmentation are commonly seen in dermatology, both in the public and private sector, and may negatively affect patients’ quality of life. Pigmentary disorders represent one of the top five most common dermatologic conditions diagnosed in Africans and African-Americans (Alexis et al., 2007, Dlova et al., 2015b, Halder and Nootheti, 2003). Many studies have been published on the spectrum and prevalence of pigmentary disorders in the Western hemisphere, but little is known about the spectrum of pigmentary disorders in South Africa’s second most populous province, KwaZulu Natal.

The increasing significance of pigmentary disorders worldwide led us to prospectively describe the epidemiology of pigmentary disorders in five major referral public hospitals in Durban, the third most populous city in South Africa and the largest city in the province of KwaZulu Natal. Durban is uniquely situated to study pigmentary disorder rates due to its unique racial profile: 51% of the population is black African, 25% is South Asian, 15% is white, and 9% is of mixed race.

This assessment of pigmentary disorders will assist in the future planning and delivery of limited health care resources by focusing dermatology and public health attention on the most common dyschromias. In doing so, dyschromias may be prevented or treated early to limit progression. Data gathered as part of this study will also allow for continued public health focus on the use of illicit skin bleaching creams, which are commonly used to treat some dyschromias (Dlova et al., 2015a).

Methods

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal. A total of 304 patients of primarily African and Indian descent (based on patient self identification) were consecutively enrolled into the study out of 3814 dermatology patients seen at five large public health hospitals over a 3-month period. Written informed consent was obtained. The data were entered and analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2007.

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study conducted over a 3-month period. Data were collected using a piloted questionnaire completed by examining doctors after patient consultation. The questionnaire included basic demographics, presenting complaint, HIV status, and specific dermatologic disorder. Only patients who presented with new skin complaints were selected to avoid bias from prior diagnoses. If the diagnosis was unclear at first visit, a skin biopsy was performed and the patient followed up within the study period to confirm the captured diagnosis.

Results

Out of 3814 patients seen over a 3-month period, 304 patients (7.97%) were diagnosed with pigmentary disorders (frequency of disease previously published as Table 1 in Dlova et al., 2018). Of these 304 patients, 79.6% (n = 242) were adults (> 18 years) and 20.4% (n = 62) were children. The majority of patients were female (n = 229; 75.8%), and all patients aged < 18 years were students. Fifty percent of the adults (n = 121) were unemployed or housewives, and the remainder were teachers (n = 24; 10%), nurses (n = 19; 8%), domestic workers (n = 73; 30%), and students (n = 5; 2%). With regard to ethnicity, 73.3% of patients (n = 222) were black African, 21.8% (n = 66) were Indian, 2.6% (n = 8) were white, and 2.3% (n = 7) were of mixed race. Of these patients,13.0% (n = 29) were HIV positive, and the majority were Fitzpatrick phototype 4 to 6. The demographic data are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Frequency of pigmentation disorders by participant characteristics

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | ||

| Adult (≥ 18 years) | 242 | 79.6 |

| Pediatric (< 18 years) | 62 | 20.4 |

| Total | 304 | 100 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 229 | 75.8 |

| Male | 73 | 24.2 |

| Total | 302 | 100 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African | 222 | 73.3 |

| Indian | 66 | 21.8 |

| White | 8 | 2.6 |

| Mixed race | 7 | 2.3 |

| Total | 303 | 100 |

| HIV status (4 hospitals only) | ||

| Positive | 29 | 13.0 |

| Negative | 194 | 87.0 |

| Total | 223 | 100 |

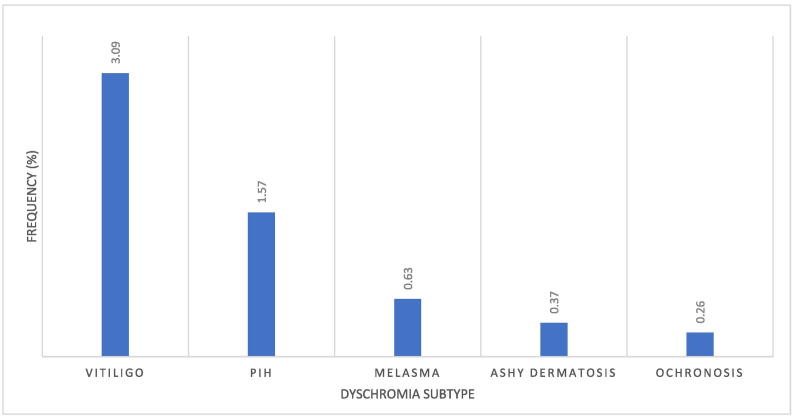

Vitiligo was the most frequently observed dyschromia during the study period (n = 118; 3.09%). Other subtypes of dyschromia diagnosed during the study period included postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH; n = 60; 1.6%) and melasma (n = 24; 0.6%). Ochronosis was diagnosed in 10 cases (0.3%). Figure 1 shows the spectrum of dyschromia diagnoses over the study period.

Fig. 1.

Dyschromias by subtype.

Discussion

Generally, pigmentary disorders are common in patients with skin of color. Moreover, the increased visibility within this population often causes significant psychological distress (Davis and Callender, 2010). Dyschromias are the third most common dermatologic diagnosis in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, (after acne and eczematous eruptions) with an estimated prevalence in the published literature of 11.6% (Dlova et al., 2018). Our study determined an estimated prevalence of 8.0% in a hospital clinic population, which is similar to the data in research conducted in other countries with a large population of patients with skin of color (Dunwell and Rose, 2003, Ogunbiyi et al., 2004, Yahya, 2007).

A Nigerian epidemiologic study estimated the frequency of pigmentary skin disorders to be 8.6% (Ogunbiyi et al., 2004). A study in the United Arab Emirates documented a 5.4% frequency of pigmentary disorders (Abu Share'ah and Abdel Dayem, 1991), and research from Saudi Arabia showed a frequency of 9.7% (Alakloby, 2005). Other studies have shown higher frequency rates, with a Jamaican study estimating the prevalence of pigmentary disorders to be 16.6% (Dunwell and Rose, 2003). A U.S. study of black patients found that dyschromias (not including vitiligo) were diagnosed with a frequency of 19.9% (Alexis et al., 2007). Comparatively, in a survey study of a U.S. sample of white patients, dyschromias were not even listed in the top10 dermatologic diagnoses (Dlova et al., 2015b).

A total of 3.1% of patients in the study sample (n = 118) were diagnosed with vitiligo, which was the most common dermatologic diagnosis in the present study. Of note, the current percentage is less than the prevalence of 5.7% estimated in a 2004 Nigerian epidemiologic study (Ogunbiyi et al., 2004). In another study of patients with skin of color, a Michigan study of Arab-Americans showed a frequency of vitiligo of 2.0% (El-Essawi et al., 2007). Of note, a 2016 meta-analysis showed that vitiligo rates are higher in African countries than anywhere else in the world (Zhang et al., 2016). This is consistent with a 2015 study that found that vitiligo occurred significantly more often in black patients within the African continent compared with those in North America (Dlova et al., 2015b).

Within our sample, 1.57% of patients were diagnosed with PIH. Comparatively, a 2003 U.S. study demonstrated a PIH prevalence of 9% in African Americans (Halder and Nootheti, 2003). A 2003 Jamaican study reported a 16.6% estimated prevalence of dyschromias, with > 50% of dyschromias attributable to PIH (Dunwell and Rose, 2003). Similarly to vitiligo, the increased visibility of PIH in patients with higher Fitzpatrick skin types leads to frequent dermatology visits, decreased self-image, and diminished quality of life (Davis and Callender, 2010).

Melasma is described as symmetric grey-brown hyperpigmentation, typically on the face, that is frequently seen in patients with skin of color, particularly women. A total of 0.6% of patients in our study were diagnosed with melasma. General estimations of global melasma prevalence rates range from 1% in the general population to 9% to 50% in at-risk populations. Risk factors include pregnancy, ultraviolet ray exposure, and darker skin phenotype (Ogbechie-Godec and Elbuluk, 2017). The melasma prevalence rate of 0.6% is much less than figures documented in other research studies in other countries. This could be because melasma can be considered a cosmetic skin condition like PIH and most public hospitals do not offer treatment for melasma. In a 2015 study of 6600 participants by Dlova et al. (2015b) in the same province but in the private sector, the prevalence of melasma was 4%.

Research in Ethiopia showed a 1.5% prevalence of melasma (Hiletework, 1998). In addition, a melasma study in Saudi Arabia found a prevalence of 2.9% (Parthasaradhi and Al Gufai, 1998), but an Arab-American population was found to have a melasma prevalence of 14.5% (El-Essawi et al., 2007). One study found that men represent only 10% of the melasma population, incidentally with low-testosterone documented in this group (Awosika et al., 2017, Sarkar et al., 2010).

Although exogenous ochronosis is a result of inappropriate and long-term use of hydroquinone, it presents with nonmelanin dyschromia. We would like to pay special attention to exogenous ochronosis because of its relevance in the South African dermatology landscape. Ochronosis appears as blue-black pigmented deposits that are most frequently found on the face after use of skin-lightening agents, such as corticosteroids, mercury, or hydroquinone. Although not a disorder of pigmentation, the appearance of ochronosis as a complication of treatment or self-initiated skin-lightening regimens can be quite worrisome to patients and prompt a dermatology consultation.

Ochronosis is quite a rare diagnosis in the United States (Vashi and Kundu, 2013). A 2006 literature review found that, out of 789 documented worldwide cases, only 22 diagnoses were made in the United States (Levitt, 2007). Ochronosis was the least frequent dermatologic diagnosis in the Durban study sample, with a rate of 0.3%. Other countries with large populations with skin of color, such as Ghana, have been shown to have higher rates of exogenous ochronosis—one study showed a frequency of 0.9% (Doe et al., 2001). Interestingly, a 1989 study found that, within a sample of patients visiting a dermatology clinic, a high proportion of women were diagnosed with exogenous ochronosis compared with men (Hardwick et al., 1989). The low prevalence of exogenous ochronosis in Durban is likely attributable to recent notable South African public health efforts dedicated to eliminating the sale and availability of hydroquinone-containing products on the market.

Of note, women made up 75.8% of the patient sample. Although previously thought to be equal in affecting both sexes, current research shows that pigmentary disorders seem to be more prevalent in women (Amer and Metwalli, 2000, Badreshia-Bansal and Draelos, 2007, Dlova et al., 2012, Dunwell and Rose, 2003, Hermanns et al., 2002, Nesby-O'Dell et al., 2002). In both population and hospital-based studies, Chen et al. (2016) showed that the pooled prevalance of vitiligo was slightly higher in women than in men. In 2014, Hexsel et al. found that melasma has a strong female preponderance with a female-to-male ratio of up to 39:1. Of course, some subcategories of pigmentary disorders, such as PIH from acne keloidalis nuchae, are more common in men than women. However, based on current data, women are more likely to be concerned about pigmentary challenges and/or may be more inclined to pursue consultation and treatment for pigmentary disorders. Thus, women are more likely to be reported in the literature. Further investigation should be sought into sex differences in the epidemiology of pigmentary disorders, particularly within populations with skin of color.

Conclusion

The present study documents the spectrum of pigmentary disorders in five major dermatology outpatient public hospital skin clinics in a predominantly female South African patient sample of black and Indian ethnicities. The leading pigmentary disorders in Durban over a 3-month study period include vitiligo, PIH, and melasma. A limitation of this study includes selection bias, because all subjects were clinic patients in a large urban setting, as well as a short study period. As such, our findings cannot be generalized to South Africa as a whole and may not represent the true prevalence of the disease in the population. True community studies and long-term cohort studies are needed to determine the real prevalence of pigmentary disorders in this population and the significant risk factors for these disorders.

A study of pigmentary disorders is important, particularly within populations with skin of color because variances in pigment are much more noticeable in this population group. Knowledge of current pigmentary disorders in KwaZulu-Natal will undoubtedly improve the diagnostic and therapeutic management of patients who reside not only in this province but in South Africa as a whole. The judicious allocation of resources and effective dermatology/public health planning are critical to best serve patients with a particular focus on both prevention and treatment. Finally, an understanding of national and international differences in pigmentary disorders may help provide insights into their pathogenesis.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Funding

None.

Study Approval

The authors confirm that any aspect of the work covered in this manuscript that has involved human patients has been conducted with the ethical approval of all relevant bodies.

Footnotes

HUMAN SUBJECTS: No human subjects were included in this study. No animals were used in this study.

References

- Abu Share'ah A.M., Abdel Dayem H. The incidence of skin diseases in Abu Dhabi (United Arab Emirates) Int J Dermatol. 1991;30(2):121–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1991.tb04223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alakloby O.M. Pattern of skin diseases in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2005;26(10):1607–1610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexis A.F., Sergay A.B., Taylor S.C. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: A comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80(5):387–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amer M., Metwalli M. Topical liquiritin improves melasma. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39(4):299–301. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awosika O., Burgess C.M., Grimes P.E. Considerations when treating cosmetic concerns in men of color. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(Suppl. 2):S140–S150. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badreshia-Bansal S., Draelos Z.D. Insight into skin lightening cosmeceuticals for women of color. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6(1):32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen T., Grau C., Suprun M., Silverberg N.B. Vitiligo patients experience barriers in accessing care. Cutis. 2016;98(6):385–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E.C., Callender V.D. Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: A review of the epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment options in skin of color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3(7):20–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlova N., Hamed S., Tsoka-Gwegweni J., Grobler A. Skin lightening practices: An epidemiological study of South African women of African and Indian ancestries. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(S2):2–9. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlova N.C., Chateau A., Khoza N., Skenjane A., Mkhize Z., Katibi O.S. Prevalence of skin diseases treated at public referral hospitals in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(1):e1–e2. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlova N.C., Hendricks N.E., Martincgh B.S. Skin-lightening creams used in Durban. South Africa Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(Suppl. 1):51–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05566.x. 56–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlova N.C., Mankahla A., Madala N., Grobler A., Tsoka-Gwegweni J., Hift R.J. The spectrum of skin diseases in a black population in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(3):279–285. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe P.T., Asiedu A., Acheampong J.W., Rowland Payne C.M. Skin diseases in Ghana and the UK. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40(5):323–326. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwell P., Rose A. Study of the skin disease spectrum occurring in an Afro-Caribbean population. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42(4):287–289. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Essawi D., Musial J.L., Hammad A., Lim H.W. A survey of skin disease and skin-related issues in Arab Americans. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(6):933–938. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder R.M., Nootheti P.K. Ethnic skin disorders overview. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(6 Suppl):S143–S148. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick N., Van Gelder L.W., Van der Merwe C.A., Van der Merwe M.P. Exogenous ochronosis: An epidemiological study. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120(2):229–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb07787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanns J.F., Petit L., Pierard-Franchimont C., Paquet P., Pierard G.E. Assessment of topical hypopigmenting agents on solar lentigines of Asian women. Dermatology. 2002;204(4):281–286. doi: 10.1159/000063359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hexsel D., Lacerda D.A., Cavalcante A.S., Machado Filho C.A., Kalil C.L., Ayres E.L. Epidemiology of melasma in Brazilian patients: A multicenter study. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(4):440–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiletework M. Skin diseases seen in Kazanchis health center. Ethiop Med J. 1998;36(4):245–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt J. The safety of hydroquinone: A dermatologist's response to the 2006 Federal Register. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(5):854–872. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesby-O'Dell S., Scanlon K.S., Cogswell M.E., Gillespie C., Hollis B.W., Looker A.C. Hypovitaminosis D prevalence and determinants among African American and white women of reproductive age: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(1):187–192. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbechie-Godec O.A., Elbuluk N. Melasma: An up-to-date comprehensive review. Dermatol Ther. 2017;7(3):305–318. doi: 10.1007/s13555-017-0194-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunbiyi A.O., Daramola O.O., Alese O.O. Prevalence of skin diseases in Ibadan, Nigeria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(1):31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasaradhi A., Al Gufai A.F. The pattern of skin diseases in Hail Region, Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 1998;18(6):558–561. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1998.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar R., Puri P., Jain R.K., Singh A., Desai A. Melasma in men: A clinical, aetiological and histological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(7):768–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashi N.A., Kundu R.V. Facial hyperpigmentation: Causes and treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169(Suppl. 3):41–56. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahya H. Change in pattern of skin disease in Kaduna, north-central Nigeria. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46(9):936–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Cai Y., Shi M., Jiang S., Cui S., Wu Y. The prevalence of vitiligo: A meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]