Abstract

Background

Deficits in cognition, social cognition, and motivation are significant predictors of poor functional outcomes in schizophrenia. Evidence of durable benefit following social cognitive training is limited. We previously reported the effects of 70 h of targeted cognitive training supplemented with social cognitive exercises (TCT + SCT) verses targeted cognitive training alone (TCT). Here, we report the effects six months after training.

Methods

111 participants with schizophrenia spectrum disorders were randomly assigned to TCT + SCT or TCT-only. Six months after training, thirty-four subjects (18 TCT + SCT, 16 TCT-only) were assessed on cognition, social cognition, reward processing, symptoms, and functioning. Intent to treat analyses was used to test the durability of gains, and the association of gains with improvements in functioning and reward processing were tested.

Results

Both groups showed durable improvements in multiple cognitive domains, symptoms, and functional capacity. Gains in global cognition were significantly associated with gains in functional capacity. In the TCT + SCT group, participants showed durable improvements in prosody identification and reward processing, relative to the TCT-only group. Gains in reward processing in the TCT + SCT group were significantly associated with improvements in social functioning.

Conclusions

Both TCT + SCT and TCT-only result in durable improvements in cognition, symptoms, and functional capacity six months post-intervention. Supplementing TCT with social cognitive training offers greater and enduring benefits in prosody identification and reward processing. These results suggest that novel cognitive training approaches that integrate social cognitive exercises may lead to greater improvements in reward processing and functioning in individuals with schizophrenia.

Keywords: Cognitive remediation, Motivation, Emotion perception, Durable

1. Introduction

Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia are recognized as a core feature of the illness and are associated with poor social and occupational outcomes. While these deficits may account for 20% to 60% of the variance in functional outcomes (Fervaha et al., 2014; Green et al., 2000; Lepage et al., 2014; Najas-Garcia et al., 2018), meta-analytic and statistical modeling studies show that social cognition is more strongly linked to community functioning, and explains unique variance in outcomes, above and beyond cognition alone (De Jong et al., 2013; Fett et al., 2011; Hoe et al., 2012; Schmidt et al., 2011). Given the significance of social cognition to functional outcomes, cognitive interventions which incorporate both cognitive and social cognitive training may be better suited to achieve clinically meaningful improvements.

Motivation also plays a significant role in the relationship between cognition, social cognition and functioning, and is more strongly linked to functioning than cognition (Najas-Garcia et al., 2018). Our group and others have shown that poor social cognitive abilities impede motivation, leading to poor functioning (Bhagyavathi et al., 2015; Fervaha et al., 2015; Gard et al., 2009; Green et al., 2012). Notably, Bhagyavathi et al. (2015) found that: (a) amotivation and other negative symptoms mediated the influence of social cognition on functional outcome, and (b) social cognition was the strongest predictor of motivation deficits and other negative symptoms. These relationships suggest that interventions that improve social cognition may result in functional improvement through improving both social cognitive and motivation pathways. These pathways are thought to be linked by shared neural circuitry supporting the processing of social stimuli, reward and motivation (e.g. Adolphs, 2009; Bhanji and Delgado, 2014; Millan and Bales, 2013; Strauss et al., 2014). We previously reported the effects of supplementing targeted cognitive training (TCT) of auditory and visual processes with social cognitive exercises (TCT + SCT), demonstrating improvements in social cognition as well as adaptive change in reward processing in the TCT + SCT group versus the TCT-only group (Fisher et al., 2017). Here, we tested whether these changes are durable six months after the intervention.

The efficacy of cognitive training and remediation interventions for improving cognition in schizophrenia in the short term is well supported (Katsumi et al., 2015; McGurk et al., 2007; Revell et al., 2015; Wykes et al., 2011). Evidence supporting the durability of gains is less robust, however, and is especially scarce for social cognitive training. The few studies that have reported on durability of outcomes following social cognitive training have focused on social skills training approaches rather than targeting the underlying neural systems supporting social cognitive processes (Combs et al., 2009; Eack et al., 2010). SocialVille, the social cognitive intervention used here, is grounded in the principles of neuroplasticity and designed to improve the fidelity of representations of socially relevant stimuli while simultaneously targeting processing speed, working memory, and attentional control (Nahum et al., 2014, Nahum et al., 2013). To our knowledge, no studies have yet examined the durability of a neuroplasticity-based social cognition training program.

The aim of this study was to compare the six-month durability of improvements in cognition, social cognition and reward processing resulting from a targeted auditory and visual training (TCT) supplemented with intensive social cognitive training (TCT + SCT) versus TCT only. In addition, we examined the impact of these trainings on symptoms and functional outcomes at six months post-training. We hypothesized that a) both groups would show durable gains in cognition, b) the TCT + SCT group would show durable gains in social cognitive domains relative to the TCT-only group and c) the TCT + SCT group would show greater gains in reward processing and functioning relative to the TCT-only group at six-month follow up.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

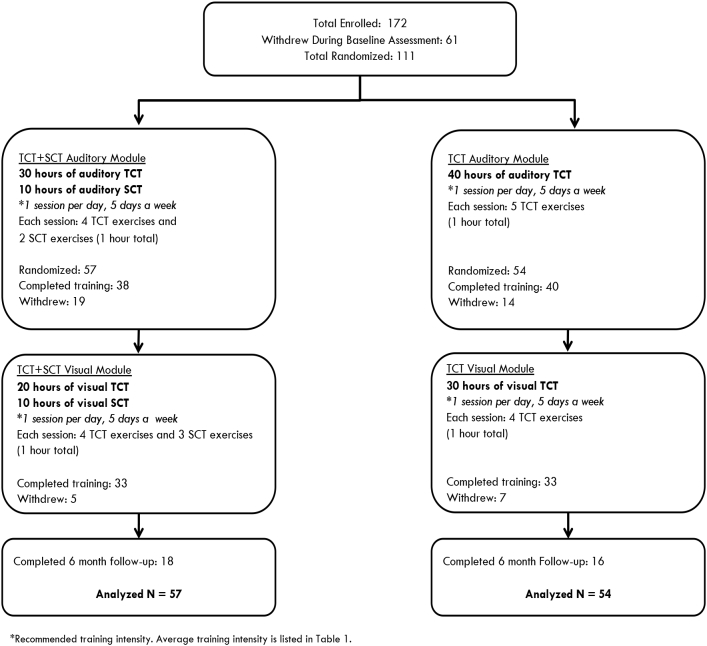

One hundred and eleven clinically stable participants with diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or psychosis not otherwise specified (NOS) were recruited from community outpatient mental health clinics (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02105779). All participants gave written informed consent and underwent a series of baseline clinical and cognitive assessments. Participants were stratified by age, education, and gender and randomly assigned to either the targeted cognitive training plus social cognition training (TCT + SCT) condition or the targeted cognitive training only condition (TCT-only). Participants reported no prior cognitive remediation treatment. All participants received $5 at the end of each successful day of training, and an additional $20 bonus for every fifth day of training, which was contingent on attendance only. A CONSORT diagram of enrollment and allocation is shown in Fig. 1. Demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1 and medication regimens are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram of study participants.

Table 1.

Demographics of Targeted Cognitive + Social Cognitive Training Participants (TCT + SCT) and Targeted Cognitive Training only participants (TCT).

| TCT + SCT (N = 57) Mean (SD) | TCT-only (N = 54) Mean (SD) | t-Test (p-Value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female (N)/male (N)a | 13/44 | 19/35 | (0.21) |

| Age | 44.08 (13.05) | 42.37 (12.65) | 0.70 (0.48) |

| Years of education | 13.77 (2.23) | 13.61 (2.26) | 0.38 (0.71) |

| Wechsler Test of Adult Reading—Premorbid IQ Estimate | 102.04 (11.75) | 102.51 (11.06) | −0.22 (0.83) |

| Diagnosisb | 1.48 (0.48) | ||

| Schizophrenia (N) | 39 | 31 | |

| Schizoaffective disorder (N) | 17 | 22 | |

| Psychosis NOS (N) | 1 | 1 | |

| Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale Total | 64.90 (17.00) | 62.17 (14.31) | 0.90 (0.37) |

| Quality of Life Scale — Average Item Rating | 3.10 (1.05) | 3.28 (1.11) | −0.84 (0.40) |

| Social Functioning Scale — Average Subscale Total | 108.03 (8.22) | 107.92 (8.75) | 0.08 (0.94) |

| Module 1 Dose (hours of training) | 31.38 (15.63) | 33.51 (13.04) | −0.79 (0.44) |

| Module 1 Weeks of training | 11.88 (6.79) | 13.12 (7.63) | −0.91 (0.37) |

| Module 1 Training intensity (hours/week) | 2.85 (1.33) | 3.08 (1.71) | −0.79 (0.43) |

| Module 2 Dose (hours of training) | 27.18 (9.56) | 25.77 (10.22) | 0.62 (0.54) |

| Module 2 Weeks of training | 11.51 (7.12) | 10.10 (7.92) | 0.815 (0.42) |

| Module 2 Training intensity (hours/week) | 2.97 (1.59) | 3.36 (1.70) | −0.994 (0.32) |

Fisher's exact test results.

Chi-square test results.

2.2. Interventions

The cognitive and social cognitive training was provided by PositScience, Inc. Social cognition training utilized the SocialVille online program (Nahum et al., 2014). The TCT + SCT group received 30 h of the general auditory exercises supplemented with 10 h of auditory social cognition exercises, followed by 20 h of general visual exercises supplemented with 10 h of visual social cognition exercises. The TCT-only group received 40 h of the general auditory exercises, followed by 30 h of the general visual exercises (Fig. 1). A description of the auditory, visual, and social cognition exercises is provided in the Supplemental Methods. Participants were asked to complete 1 h of training per day, five days per week. The sequence and hours of training, and number of exercises per session are shown in Fig. 1.

Average hours of training completed and training intensity during the auditory and visual modules are listed in Table 1. Seventy participants trained at the lab on laptops (39 TCT + SCT, 31 TCT-only) and 41 participants completed training off-site via iPad (18 TCT + SCT, 23 TCT-only). The difference in the number of participants in each group who trained via iPad was non-significant (Fisher's Exact Test p = 0.25). The iPad version of the exercises differed slightly from the laptop version in its user interface and graphics, due to developments in Posit Science's software packages. However, the ‘active ingredients’ of each exercise were similar across platforms, including the stimulus sets, stimulus progressions, adaptivity, and exercise logic.

2.3. Assessments

A diagnostic assessment was administered at baseline. All other assessments were administered at baseline, after 40 h of training (the auditory module), after 70 h of training (both modules), and 6 months after all training.

2.3.1. Diagnostic assessment

Each participant received a standardized diagnostic evaluation using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (First et al., 2002) performed by research personnel trained in research diagnostic techniques, as well as review of clinical records and interview with patient informants (e.g., psychiatrists, therapists, social workers).

2.3.2. Cognitive measures

The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) (Nuechterlein et al., 2008) was administered at all time points. All measures were distinct from tasks practiced during training. In addition to the learning trials, the verbal and visual memory trials (i.e. delayed recall) of the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-R (HVLT-R) and Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-R (BVMT-R) were administered. Alternate forms of the HVLT-R, BVMT-R, and Nab Mazes tests were administered and counterbalanced. All tests were scored and re-scored by a second staff member blind to the first scoring.

2.3.3. Social cognition measures

Social cognition was assessed with the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) Perceiving Emotions and Managing Emotions (Mayer et al., 2003) the Prosody Identification Test (PROID) (Juslin and Laukka, 2001), and the Faux Pas Recognition Test (theory of mind) (Gregory et al., 2002; Stone et al., 1998). Thirty-eight TCT + SCT and 40 TCT-only participants completed the PROID which was added to the battery after the study was initiated. Alternate forms of the Faux Pas Recognition Test were created and counterbalanced.

2.3.4. Motivation measures of reward processing

The Temporal Experience of Pleasure Scale (TEPS) (Gard et al., 2006) was used as a proxy measure of reward processing related to motivated behavior. The TEPS assesses anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Anticipatory pleasure is closely linked to motivation and goal-directed behavior while consummatory pleasure is associated with satiation (i.e. wanting versus liking).

2.3.5. Symptom and functional outcome measures

Symptom severity was assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987). Functional capacity was assessed with the University of California, San Diego, Performance-Based Skills Assessment—Brief (UPSA-Brief) (Mausbach et al., 2007). Quality of life was assessed using an abbreviated version of the Quality of Life Scale (QLS) (Bilker et al., 2003; Heinrichs et al., 1984) and the Social Functioning Scale (Birchwood et al., 1990).

Research staff who conducted clinical or cognitive testing first completed extensive training (e.g., scoring videotaped sessions, observation of sessions, and participating in mock sessions). In our laboratory, intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) are >0.85 for the PANSS and QLS Total and subscale scores. Participants and assessment personnel were blind to group assignment.

2.3.6. Target engagement of auditory cortical processing efficiency

Target engagement – i.e., improvement in auditory cortical processing efficiency - was monitored at baseline and after 20 h of training using auditory processing speed (APS). This measure consists of a time-order judgment of a sequence of two frequency modulated tones and is considered a measure of successive signal interference/forward and backward masking. Detailed methods on APS measurement are provided elsewhere (Fisher et al., 2014).

2.4. Statistical analyses

The MCCB computerized scoring program was used to compute age and gender adjusted T-scores and the composite scores. All variables were screened and normally distributed after winsorising of outlying values. Independent Samples t-tests tested for group differences in demographic variables, hours of training, and training intensity. Fisher's Exact Test or Chi-Square Test tested for group differences in categorical variables. To assess effects of attrition, we also tested for differences in demographic variables, hours of training, training intensity and clinical and cognitive variables between study completers and participants who dropped out prior to the six-month assessment. An intent-to-treat analysis was conducted using a linear mixed-effects model with group and time as fixed factors. Model parameters were estimated using restricted maximum likelihood. Participant groups were compared on the change in the MCCB T-scores (listed in Table 2), measures of social cognition and motivation, the PANSS, UPSA-Brief, QLS, SFS totals and subscale scores. Effect sizes (Cohen's d) were calculated using mean change scores (baseline to six-month follow up) and change score standard deviations. Change in APS was tested with Paired Samples t-test. Exploratory analyses tested for associations between the change in global cognition and changes in symptoms and functioning in the total sample, and whether changes in social cognition and reward processing were associated with changes in symptoms and functioning in the TCT + SCT group using Pearson correlations. Exploratory analyses were uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

Table 2.

Scores on cognitive, social cognitive, and reward processing outcome measures, and symptom ratings and functional outcomes at baseline, 40 h and training, 70 h of training, and 6 month follow up in the Targeted Cognitive Training plus Social Cognition Training (TCT + SCT) or Targeted Cognitive Training only (TCT-only) groups.

| Outcome measures | TCT + SCT |

TCT only |

Main effects of time p value | Group × time interaction p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline mean (SE) N = 57 |

40 h mean (SE) N = 38 | 70 h mean (SE) N = 33 | 6 month follow up N = 18 | Baseline mean (SE) N = 54 | 40 h mean (SE) N = 40 | 70 h mean (SE) N = 33 | 6 month follow up N = 16 | |||

| MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Batterya | ||||||||||

| Global cognition | 29.41 (1.89) |

31.57 (2.46) |

32.91 (2.58) |

36.06 (2.87) |

31.84 (1.91) |

35.05 (2.03) |

36.00 (2.69) |

37.5 (2.81) |

<0.001 | 0.43 |

| Attention | 37.66 (1.63) |

37.78 (2.31) |

40.25 (2.08) |

41.38 (3.06) |

39.36 (1.89) |

43.00 (2.10) |

42.00 (2.39) |

43.38 (2.62) |

0.001 | 0.65 |

| Speed of processing | 34.75 (1.90) |

34.56 (2.65) |

35.47 (2.90) |

38.13 (2.43) |

36.62 (1.66) |

39.59 (2.31) |

42.16 (2.70) |

42.75 (3.89) |

<0.001 | 0.13 |

| Working memory | 39.61 (1.67) |

39.32 (1.98) |

41.69 (2.32) |

38.63 (3.71) |

39.97 (1.79) |

41.70 (1.85) |

42.49 (2.02) |

43.63 (3.02) |

0.08 | 0.22 |

| Verbal learning | 36.45 (1.09) |

38.11 (1.70) |

38.72 (1.55) |

41.31 (2.36) |

37.91 (1.27) |

40.08 (1.19) |

40.33 (2.08) |

37.06 (2.11) |

0.19 | 0.08 |

| Verbal memoryb | 29.87 (2.04) |

28.72 (2.73) |

29.92 (2.69) |

30.50 (3.29) |

32.52 (2.10) |

34.20 (2.56) |

33.59 (3.02) |

31.89 (3.92) |

0.58 | 0.62 |

| Visual learning | 35.63 (1.76) |

37.92 (2.02) |

42.53 (2.30) |

44.63 (3.10) |

39.44 (1.89) |

44.18 (2.34) |

43.91 (2.82) |

44.44 (3.82) |

0.001 | 0.052 |

| Visual memoryb | 33.86 (2.28) |

36.89 (2.41) |

40.53 (2.83) |

41.35 (3.64) |

38.13 (2.20) |

39.35 (2.35) |

41.95 (3.49) |

44.66 (3.91) |

0.01 | 0.2 |

| Problem solving | 39.61 (1.31) |

37.92 (1.50) |

41.75 (1.97) |

45.69 (3.22) |

41.38 (1.55) |

43.97 (1.77) |

44.22 (1.87) |

43.63 (2.30) |

<0.001 | 0.36 |

| Social cognition and reward processing measures | ||||||||||

| MSCEIT Perceiving Emotions | 42.30 (1.49) |

42.96 (2.08) |

43.03 (2.77) |

43.64 (4.90) |

44.18 (1.47) |

45.36 (1.76) |

44.81 (1.81) |

44.56 (2.11) |

0.95 | 0.25 |

| MSCEIT Managing Emotions | 40.92 (1.44) |

41.21 (1.15) |

40.12 (1.17) |

42.19 (1.89) |

38.99 (1.14) |

39.17 (1.29) |

39.69 (1.44) |

43.91 (1.79) |

0.01 | 0.82 |

| Prosody Identification Correct Responses | 31.90 (1.11) |

34.42 (2.24) |

34.92 (1.97) |

35.53 (2.22) |

34.24 (1.36) |

35.74 (1.81) |

35.35 (1.95) |

33.31 (1.57) |

0.002 | 0.01 |

| Prosody identification reaction time (ms) | 4841.45 (211.82) |

4311.19 (188.35) |

3954.28 (139.52) |

3868.57 (133.26) |

4241.88 (164.85) |

4443.43 (192.24) |

4325.06 (141.15) |

4114.56 (175.50) |

<0.0001 | 0.02 |

| Faux Pas Test Percent Correct | 74.19 (2.15) |

78.28 (2.97) |

79.89 (2.90) |

76.57 (3.98) |

76.56 (1.79) |

78.29 (2.27) |

79.06 (3.02) |

78.43 (3.54) |

0.06 | 0.77 |

| TEPS Anticipatory Pleasure | 4.05 (0.13) |

4.22 (0.13) |

4.41 (0.13) |

4.41 (0.18) |

4.34 (0.11) |

4.25 (0.14) |

4.15 (0.16) |

4.19 (0.20) |

0.21 | 0.04 |

| TEPS Consummatory Pleasure | 4.23 (0.14) |

4.34 (0.14) |

4.50 (0.15) |

4.21 (0.22) |

4.47 (0.14) |

4.34 (0.15) |

4.21 (0.16) |

4.26 (0.18) |

0.12 | 0.12 |

| Symptoms ratings | ||||||||||

| PANSS Total | 64.90 (2.25) |

63.11 (2.67) |

64.03 (3.03) |

60.07 (4.5) |

62.16 (2.00) |

60.28 (2.82) |

57.16 (2.74) |

60.57 (5.02) |

0.05 | 0.77 |

| PANSS Positive Symptoms | 15.68 (0.73) |

14.49 (0.71) |

15.33 (0.91) |

15.93 (1.5) |

14.98 (0.71) |

15.69 (0.86) |

13.65 (1.05) |

14.29 (1.55) |

0.26 | 0.97 |

| PANSS Negative Symptoms | 16.53 (0.77) |

15.84 (0.78) |

15.80 (0.84) |

14.73 (1.0) |

14.78 (0.68) |

13.81 (0.77) |

14.22 (0.83) |

16.29 (1.80) |

0.09 | 0.28 |

| PANSS General Psychopathology | 32.68 (1.17) |

32.05 (1.57) |

31.87 (1.76) |

29.4 (2.60) |

32.39 (1.10) |

31.03 (1.64) |

29.66 (1.43) |

30 (2.32) | 0.03 | 0.66 |

| Functional outcomes | ||||||||||

| UPSA-Briefc total | 69.60 (1.86) |

70.33 (2.58) |

70.75 (3.15) |

74.61 (2.81) |

70.91 (2.03) |

75.40 (2.25) |

79.03 (2.00) |

76.81 (2.95) |

0.003 | 0.98 |

| Quality of Life Scale Mean Item Score | 3.10 (0.14) |

3.14 (0.18) |

3.06 (0.18) |

3.06 (0.25) |

3.28 (0.15) |

3.27 (0.15) |

3.24 (0.20) |

3.21 (0.25) |

0.07 | 0.4 |

| Social Functioning Scale—Average Subscale Score | 107.98 (1.11) |

108.22 (1.34) |

107.98 (1.20) |

109.95 (2.18) |

107.85 (1.21) |

108.54 (1.29) |

106.64 (1.18) |

105.19 (1.74) |

0.37 | 0.31 |

MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB) Measures: Global Cognition (composite T-score across all MCCB measures); Attention (Continuous Performance Task-Identical Pairs); Speed of Processing (Trail Making Test Part A; Category Fluency Animal Naming; BACS Symbol Coding); Working Memory (Letter-Number Span; WMS-III Spatial Span); Verbal Learning (HVLT-R Immediate Recall); Visual Learning (BVMT-R Immediate Recall); Problem Solving (NAB Mazes); MSCEIT Managing Emotions.

In addition to the MCCB, verbal and visual Delayed Recall from the HVLT-R and BVMT-R were administered;

University of California, San Diego, Performance-Based Skills Assessment—Brief.

3. Results

There were no significant differences between groups in baseline demographic characteristics, cognitive measures, symptom severity, functioning, or medication regimens. There were no significant differences between groups in training intensity or attrition rate (χ2 = 0.05, p = 0.82) at the 6-month follow-up (Table 1 and Fig. 1). In terms of attrition, there were no differences in demographic variables, baseline cognitive performance, symptoms or functional outcomes between participants who dropped out at the post-training time point versus those who remained in the study (Fisher et al., 2017). Participants who completed the six-month follow up time point versus those who dropped out had significantly lower baseline scores on the prosody identification correct responses (t = −2.1, p = 0.036) and the TEPS consummatory pleasure scale (t = −3.0, p = 0.003). There were no other differences between six-month follow up completers and drop outs on demographic variables, baseline cognitive performance, symptoms or functional outcomes.

3.1. Cognition

In the total sample, significant main effects of time were found in MCCB Global Cognition (d = 0.47, p < 0.001), Attention (d = 0.31, p = 0.001), Speed of Processing (d = 0.37, p < 0.001), Visual Learning (d = 0.52, p = 0.001), Visual Memory (d = 0.42, p = 0.01), Problem Solving (d = 0.39, p < 0.001), and in Working Memory at trend level significance (d = 0.10, p = 0.08) (Table 2). A group-by-time interaction at trend level significance was found in Verbal Learning (d = 0.95, p = 0.08) and Visual Learning (d = 0.61, p = 0.052), with the TCT + SCT group showing greater improvement (Table 2).

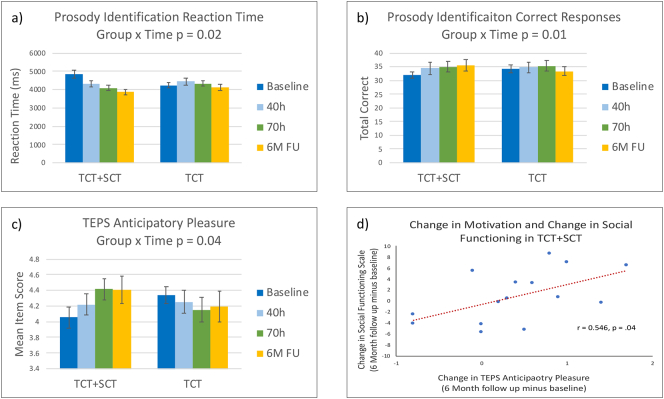

3.2. Social cognition

In the total sample, main effects of time were found in the MSCEIT Managing Emotions Scale (d = 0.35, p = 0.01) and in the Faux Pas Test at trend level significance (d = 0.14, p = 0.06). Significant group-by-time interactions were shown in the Prosody Identification Task Correct Responses (d = 1.03, p = 0.01) and Reaction Time (d = 0.03, p = 0.02), with the TCT + SCT group showing greater gains (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Performance in (a) prosody identification reaction time, (b) prosody identification correct responses, and (c) TEPS Anticipatory Pleasure score at baseline, 40 h of training, 70 h of training (post-training) and six-month follow up in the Targeted Cognitive Training + Social Cognition Training (TCT + SCT) and TCT-only participant groups. In the TCT + SCT group, changes in anticipatory pleasure significantly correlated with changes in social functioning from baseline to 6-month follow up (d).

3.3. Reward processing

A significant group-by-time interaction was found on the TEPS Anticipatory Pleasure Scale (d = 0.47, p = 0.04), with the TCT + SCT group showing greater gains (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

3.4. Symptoms and functioning

Significant main effects of time were shown in the PANSS Total (d = −0.20, p = 0.05), PANSS General Psychopathology Subscale (d = −0.35, p = 0.03), and in the UPSA-Brief (d = 0.39, p = 0.003), with both groups showing improvement (Table 2).

3.5. Target engagement

The auditory processing speed measure was available at baseline and after 20 h of auditory training in 58 subjects. There was a significant decrease in the APS threshold from baseline (Mean = 131.13 ms, SD = 117.69 ms) to 20 h (Mean = 73.06 ms, SD = 69.97 ms; t(57) = −4.391, p < 0.001) in the total sample. This improvement was not associated with gains in global cognition, symptoms or functioning at post-training or six-month follow-up.

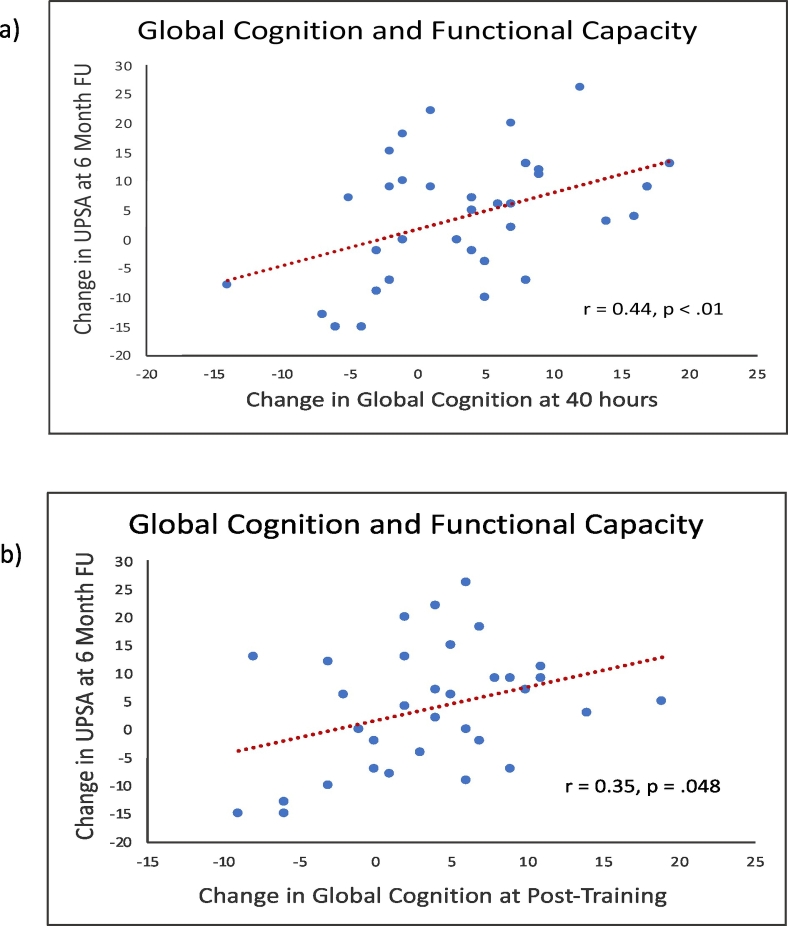

3.6. Exploratory analyses

In the total sample, changes in the UPSA-Brief from baseline to six-month follow-up were significantly associated with changes in Global Cognition from baseline to completion of the auditory training module at 40 h of training (r = 0.44, p < 0.01), and from baseline to post-training (r = 0.35, p = 0.05) (Fig. 3). In the TCT + SCT group, changes in anticipatory pleasure were significantly associated with gains on the Social Functioning Scale from baseline to the six-month follow-up (r = 0.55, p = 0.04) (Fig. 2). All other associations were non-significant.

Fig. 3.

Associations between change in the UPSA-Brief from baseline to the six-month follow-up, and (a) change in global cognition from baseline to 40 h of training, and (b) change in global cognition from baseline to post-training, in the total sample.

4. Discussion

4.1. Targeted cognitive training results in durable cognitive improvements

Our results add to the limited evidence that computerized targeted cognitive training, delivered as a standalone treatment, can drive enduring improvements across multiple cognitive domains. The magnitude of the effects on a range of cognitive measures were in the small to moderate range from baseline to six-month follow up, suggesting that the “dosing” of 70 h of targeted cognitive training is sufficient to drive lasting improvement. We cannot rule out the influence of practice effects. However, a large pooled cohort study of MCCB practice effects showed small effects sizes of Cohen's d = 0.15 for global cognition, and domain effect sizes ranging from 0.09 for problem solving to 0.19 for speed of processing (Georgiades et al., 2017). The authors report effect sizes of 0.11 on the HVLT-R and 0.13 on the BVMT-R learning trials, which are substantially smaller than the effect sizes in this study. This suggests that our results are not due to practice effects alone. Further, the largest practice effects have been found in studies with testing intervals <1 month apart, whereas we had a lengthy six-month test interval. Practice effects have also been found to diminish with additional assessments, as employed in our study design (Georgiades et al., 2017). Finally, we used alternative forms for the HVLT-R and BVMT-R which have been shown to result in minimal practice effects (Benedict and Zgaljardic, 1998).

4.2. Supplementation with social cognition training drives durable gains in prosody identification

To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that supplementing computerized cognitive training with social cognition training can induce enduring improvements in emotion perception as measured by prosody identification. At the six-month follow up, participants in the TCT + SCT group showed significantly greater improvement in emotional prosody identification accuracy and reaction time relative to the TCT-only group. This is an important finding as patients with schizophrenia have significant impairments in detecting subtle acoustic features such as pitch (Jahshan et al., 2013). These impairments manifest in deficits of emotion discrimination based on tone of voice and are associated with negative symptoms (Kantrowitz et al., 2013). As six-month follow up completers performed significantly worse on the prosody identification correct responses measure at baseline compared to drop outs, it is unlikely that the high attrition biased these results. However, we did not find differential improvement in the MSCEIT Perceiving Emotions subscale, and both groups showed improvement over time in the Managing Emotions subscale. We may have been underpowered to detect differences in the Perceiving Emotions measure. It is also possible that due to task design characteristics of this measure, such as unlimited response time and non-social stimuli, it was not particularly sensitive to the emotion recognition improvements driven by the SocialVille exercises, which aim to improve processing speed and accuracy of socially relevant information.

4.3. Supplementation with social cognition training drives durable improvements in reward processing

An important finding of this study is that TCT + SCT participants showed significantly larger gains from baseline to six-month follow up on the TEPS Anticipatory Pleasure scale relative to the TCT-only group. To our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled trial of social cognitive training to induce durable changes in motivational systems. It is particularly significant that we found significant effects specifically in anticipatory pleasure, described as the “wanting” of an event vs the “liking” of the event, as several studies support an intact neural response to reward in schizophrenia, but impairments in anticipation of these rewards, including hypo-activation of the ventral striatal system and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, and impaired dopaminergic activity in these areas (Frost and Strauss, 2016; Gard et al., 2007; Strauss et al., 2014).

Our results support the theory suggested by several path analyses that improvements in social cognition may lead to improved motivated behavior, as opposed to amotivation impeding social cognitive abilities (Bhagyavathi et al., 2015; Gard et al., 2009; Green et al., 2012). This has significant clinical implications given the lack of successful treatment interventions for negative symptoms such as amotivation in schizophrenia and suggests that targeting social cognitive deficits may improve motivation, and that improvements in these domains may translate to improved functioning. Consistent with this model, in our exploratory analysis we found that in the TCT + SCT group, changes in anticipatory pleasure were associated with improvements in social functioning at six-month follow up. In our previous work we demonstrated training induced normalization of medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) activity during a reality monitoring task immediately after a combined auditory and social cognition training, which was associated with improved social functioning six months later (Subramaniam et al., 2012). As mPFC is an important node in the reward valuation pathway, it could be hypothesized that the association between increased anticipatory pleasure and increased social functioning found in the current study is mediated by modulated mPFC activity. Together, cognition, social cognition, and motivation are all important contributors to functional ability in schizophrenia, and our results suggest that TCT + SCT may drive enduring improvements in all three of these domains.

4.4. Targeted cognitive training results in a decrease in symptom severity, and durable gains in functional capacity

In the total sample, participants showed improvements on the PANSS Total and General symptom scales. The impact of cognitive training on symptoms has been mixed in previous reports, with meta-analytic results showing small effect sizes at post-training that are not durable at follow up (Wykes et al., 2011). In the total sample, gains in functional capacity as measured by the UPSA, endured at six-month follow up with a small-moderate effect size. Improvements in the UPSA following TCT suggest transfer of cognitive gains to tasks important for daily functioning. Consistently, we found that in the total sample improvements in global cognition after 40 and 70 h of training were associated with improvements in the UPSA at six months. However, no significant changes were found in the Quality of Life or Social Functioning Scale, and improvements in cognition were not associated with improvements on these measures, in contrast to our previous study (Fisher et al., 2010).

4.5. Study limitations and future directions

The main limitations of this study are the small sample size at the six-month follow up, and the high rates of attrition during the active study condition (35–37%) and at the six-month timepoint. While several efforts were made to contact participants for the six-month follow-up assessment, a large portion of participants were unable to be reached. To address the attrition rate in our analyses, we ensured that there were no differential attrition rates between groups, and that attrition did not result in the groups being unbalanced on any baseline demographic, cognitive, symptom or functional measures that could account for our results. Additionally, we used intent-to-treat analysis to help minimize potential bias from attrition. Second, due to our lack of control group, we cannot rule out the possibility that practice effects impacted our results. However, the MCCB cognitive testing battery is the gold standard in the field due to its consistent demonstration of high reliability and low practice effects, and practice effects may be further minimized by the long period between post-training and six-month follow up testing and by the use of alternative forms where applicable (Georgiades et al., 2017; Nuechterlein et al., 2008). Additionally, the cognitive effect sizes found in this study were substantially larger than those expected due to practice effects (Georgiades et al., 2017). Third, the generalizability of our results may also be impacted by the sociodemographic background of our sample, which included well educated individuals with a mean age of 43. Finally, this study used a large dose of training hours, and our previous results have demonstrated that significant and durable cognitive gains can be achieved with 50 h of TCT (Fisher et al., 2010). We do not yet know the optimal length and intensity to drive enduring gains—an important area for future research.

Evidence of enduring effects beyond the immediate training period is needed to support the clinical utility of cognitive training interventions. Treatments that are successful in improving real word functioning may need to go beyond improving cognition to also target social cognition and motivation systems. Our findings indicate that an intensive, targeted, and standalone cognitive training approach may lead to enduring improvements in cognition, symptoms and functional capacity in individuals with psychotic illnesses. Further, when supplemented with social cognition training, durable improvements in prosody identification and reward processing are found; and importantly, improved reward processing may drive enhanced social functioning. Future research must continue to identify the necessary cognitive and reward system targets that will translate into meaningful psychosocial gains.

Funding sources

This research was supported by NIMH R01MH082818. KM is supported by the National Institutes of Health's National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grants TL1R002493 and UL1TR002494. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health's National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. KM receives support as a Jonas Scholar 2018–2020.

Author contribution statement

Kathleen Miley: Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Visualization. Melissa Fisher: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration. Mor Nahum: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing; Elizabeth Howard: Investigation, Data Curation. Abby Rowlands: Investigation, Data Curation. Benjamin Brandrett: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing. Josh Woolley: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing. Christine I. Hooker: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing. Bruno Biagianti: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing. Ian Ramsay: Writing – Review & Editing. Sophia Vinogradov: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Project Administration, Funding Acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

Bruno Biagianti MD, PhD is Senior Scientist at Posit Science, a company that produces cognitive training and assessment software.

Drs. Vinogradov, Fisher, and Nahum have scientific collaborations with scientists at Posit Science, and do not hold any financial interests in the company.

Dr. Vinogradov serves on Scientific Advisory Boards for the following organizations: Mindstrong, Inc., Alkermes, Inc., and Psyberguide.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scog.2019.100171.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Adolphs R. The social brain: neural basis of social knowledge. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009;60:693–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict R.H.B., Zgaljardic D.J. Practice effects during repeated administrations of memory tests with and without alternate forms. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1998;20:339–352. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.3.339.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagyavathi H.D., Mehta U.M., Thirthalli J., Kumar C.N., Kumar J.K., Subbakrishna D.K., Gangadhar B.N. Cascading and combined effects of cognitive deficits and residual symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia - a path-analytical approach. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229:264–271. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhanji J.P., Delgado M.R. The social brain and reward: social information processing in the human striatum. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2014;5:61–73. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilker W.B., Brensinger C., Kurtz M.M., Kohler C., Gur R.C., Siegel S.J., Gur R.E. Development of an abbreviated schizophrenia quality of life scale using a new method. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:773–777. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birchwood M., Smith J., Cochrane R., Wetton S., Copestake S. The Social Functioning Scale. The development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Britsh J. Psychiatry. 1990;157:853–859. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combs D.R., Penn D.L., Tiegreen J.A., Nelson A., Ledet S.N., Basso M.R., Elerson K. Stability and generalization of Social Cognition and Interaction Training (SCIT) for schizophrenia: six-month follow-up results. Schizophr. Res. 2009;112:196–197. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong J.S.J., De Gelder B.B., Hodiamont P.P.P.G. Sensory processing, neurocognition, and social cognition in schizophrenia: towards a cohesive cognitive model. Schizophr. Res. 2013;146:209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eack S.M., Greenwald D.P., Hogarty S.S., Keshavan M.S. One-year durability of the effects of cognitive enhancement therapy on functional outcome in early schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2010;120:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fervaha G., Foussias G., Agid O., Remington G. Motivational and neurocognitive deficits are central to the prediction of longitudinal functional outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2014;130:290–299. doi: 10.1111/acps.12289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fervaha G., Siddiqui I., Foussias G., Agid O., Remington G. Motivation and social cognition in patients with schizophrenia. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2015;21:436–443. doi: 10.1017/S1355617715000375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fett A.K.J., Viechtbauer W., Dominguez M. de G., Penn D.L., van Os J., Krabbendam L. The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2011;35:573–588. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M.B., Spritzer R.L., Gibbon M., Williams J. Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, New York: 2002. Structure Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis 1 Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M., Holland C., Subramaniam K., Vinogradov S. Neuroplasticity-based cognitive training in schizophrenia: an interim report on the effects 6 months later. Schizophr. Bull. 2010;36:869–879. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M., Loewy R., Carter C., Lee A., Ragland J.D., Niendam T.…Vinogradov S. Neuroplasticity-based auditory training via laptop computer improves cognition in young individuals with recent onset schizophrenia. Schizophrenia bulletin. 2014;41(1):250–258. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M., Nahum M., Howard E., Rowlands A., Brandrett B., Kermott A., Woolley J., Vinogradov S. Supplementing intensive targeted computerized cognitive training with social cognitive exercises for people with schizophrenia: an interim report. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2017;40:21–32. doi: 10.1037/prj0000244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost K.H., Strauss G.P. A review of anticipatory pleasure in schizophrenia. Curr. Behav. Neurosci. Reports. 2016;3:232–247. doi: 10.1007/s40473-016-0082-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard D.E., Gard M.G., Kring A.M., John O.P. Anticipatory and consummatory components of the experience of pleasure: a scale development study. J. Res. Pers. 2006;40:1086–1102. [Google Scholar]

- Gard D.E., Kring A.M., Gard M.G., Horan W.P., Green M.F. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: distinctions between anticipatory and consummatory pleasure. Schizophr. Res. 2007;93:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard D.E., Fisher M., Garrett C., Genevsky A., Vinogradov S. Motivation and its relationship to neurocognition, social cognition, and functional outcome in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2009;115:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades A., Davis V.G., Atkins A.S., Khan A., Walker T.W., Loebel A., Haig G., Hilt D.C., Dunayevich E., Umbricht D., Sand M., Keefe R.S.E. Psychometric characteristics of the MATRICS consensus cognitive battery in a large pooled cohort of stable schizophrenia patients. Schizophr. Res. 2017;190:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M.F., Kern R.S., Braff D.L., Mintz J. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the “right stuff”? Schizophr. Bull. 2000;26:119–136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M.F., Hellemann G., Horan W.P., Lee J., Wynn J.K. From perception to functional outcome in schizophrenia: modeling the role of ability and motivation. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2012;69:1216–1224. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory C., Lough S., Stone V., Erzinclioglu S., Martin L., Baron-Cohen S., Hodges J.R. Theory of mind in patients with frontal variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: theoretical and practical implications. Brain. 2002;125:752–764. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs D., Hanlon T., Carpenter W. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenia deficit syndrome. Schizophr. Bull. 1984;10:388–396. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.3.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoe M., Nakagami E., Green M.F., Brekke J.S. The causal relationships between neurocognition, social cognition and functional outcome over time in schizophrenia: a latent difference score approach. Psychol. Med. 2012;42:2287–2299. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahshan C., Wynn J.K., Green Relationship between auditory processing and affective prosody in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2013;143:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juslin P.N., Laukka P. Impact of intended emotion intensity on cue utilization and decoding accuracy in vocal expression of emotion. Emotion. 2001;1:381–412. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.4.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantrowitz J.T., Leitman D.I., Lehrfeld J.M., Laukka P., Juslin P.N., Butler P.D., Silipo G., Javitt D.C. Reduction in tonal discriminations predicts receptive emotion processing deficits in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr. Bull. 2013;39:86–93. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsumi A., Hoshino H., Fujimoto S., Niwa S.-I. Efficacy of cognitive remediation in schizophrenia: a short review of its variable effects according to cognitive domain. Open J. Psychiatry. 2015;5:170–176. [Google Scholar]

- Kay S., Fiszbein A., Opler L. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepage M., Bodnar M., Bowie C.R. Neurocognition: clinical and functional outcomes in schizophrenia. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2014;59:5–12. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach B.T., Harvey P.D., Goldman S.R., Jeste D.V., Patterson T.L. Development of a brief scale of everyday functioning in persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr. Bull. 2007;33:1364–1372. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer J.D., Caruso D.R., Salovey P.S., Sitarenios G. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion. 2003;3:97–106. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk S.R., Twamley E.W., Sitzer D.I., McHugo G.J., Mueser K.T. NIH public access. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2007;164:1791–1802. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07060906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan M.J., Bales K.L. Towards improved animal models for evaluating social cognition and its disruption in schizophrenia: the CNTRICS initiative. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013;37:2166–2180. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahum M., Lee H., Merzenich M.M. Progress in Brain Research. 1st ed. Elsevier B.V; 2013. Principles of neuroplasticity-based rehabilitation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahum M., Fisher M., Loewy R., Poelke G., Ventura J., Keith H., Hooker C.I., Green M.F., Merzenich M. A novel, online social cognitive training program for young adults with schizophrenia: a pilot study. Schizophr. Res. Cogn. 2014;1:e11–e19. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najas-Garcia A., Gómez-Benito J., Huedo-Medina T.B. The relationship of motivation and Neurocognition with functionality in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Community Ment. Health J. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10597-018-0266-4. Springer US. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein K.H., Green M.F., Kern R.S., Baade L.E., Barch D.M., Cohen J.D., Essock S., Fenton W.S., Frese F.J., Gold J.M., Goldberg T., Heaton R.K., Keefe R.S.E., Kraemer H., Mesholam-Gately R., Seidman L.J., Stover E., Weinberger D.R., Young A.S., Zalcman S., Marder S.R. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165:203–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revell E.R., Neill J.C., Harte M., Khan Z., Drake R.J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of cognitive remediation in early schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2015;168:213–222. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S.J., Mueller D.R., Roder V. Social cognition as a mediator variable between neurocognition and functional outcome in schizophrenia: empirical review and new results by structural equation modeling. Schizophr. Bull. 2011;37 doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone V.E., Baron-Cohen S., Knight R.T. Frontal lobe contributions to theory of mind. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1998;10:640–656. doi: 10.1162/089892998562942. (doi:Thesis_references-Converted #463) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss G.P., Waltz J.A., Gold J.M. Vol. 40. 2014. A Review of Reward Processing and Motivational Impairment in Schizophrenia; pp. 107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam K., Luks T.L., Fisher M., Simpson G.V., Nagarajan S., Vinogradov S. Computerized cognitive training restores neural activity within the reality monitoring network in schizophrenia. Neuron. 2012;73:842–853. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykes T., Huddy V., Cellard C., McGurk S., Czobor P. 2011. A Meta-Analysis of Cognitive Remediation for Schizophrenia: Methodology and Effect Sizes; pp. 472–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material