Abstract

Objective

To determine the potential and limitations of Primary Health Care professionals to identify situations of violence against women.

Location

A municipality of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil.

Design

Descriptive and exploratory study with a qualitative approach.

Participants

Twenty-one health professionals of three Family Health Strategy units, as well as one Basic Health Unit. The inclusion criterion consisted of being a health worker in these services. The exclusion criterion was to be absent from work by any kind type license during the period of data production.

Method

The technique used to produce data was individual, semi-structured, interviews in order to collect sociodemographic data and the monitoring by professionals related to the potentials and limitations to identify violence situations. The data collection was suspended based on the saturation criterion. The data were systematized and analyzed by the content analysis technique, according to the analytical categories of health care network and gender.

Results

The potential to identify themes were: professional experience, receptive atmosphere, bonding, and listening to the reports of women, children and/or neighbors and observing their behavior; to identify the lesions; prenatal consultations; and home visits. As to the limitations: silence, denial/non-recognition of violence, lack of complaints by women; fear and guilt; flaws and unpreparedness of the health team; and fear due to the presence of aggressor.

Conclusions

It is urgent to recognize the potential of Primary Care and to promote the qualification of professionals in order to identify the situation among visible and invisible complaints, leading to the confrontation of violence.

Keywords: Violence against women, Attitude of health personnel, Battered women, Women's health, Delivery of health care

Resumen

Objetivo

Conocer potencialidades y límites para identificar de situaciones de violencia contra las mujeres por profesionales de Atención Primaria a la Salud.

Emplazamiento

Un municipio de Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil.

Diseño

Estudio exploratorio y descriptivo con enfoque cualitativo.

Participantes

21 Profesionales de la salud de 3 unidades de Estrategia Salud de la Familia y una Unidad Básica de Salud. Criterio de inclusión: ser trabajador de salud en esos servicios. Criterio de exclusión: estar ausente del trabajo por licencia de cualquier naturaleza durante el período de generación de datos.

Método

Entrevistas semiestructuradas individuales para recopilar datos sociodemográficos y profesionales relacionados con potencialidades y límites para identificar situaciones de violencia. La recolección de datos fue cerrada mediante el criterio de saturación. Los datos fueron sistematizados y analizados a través del análisis de contenido según las categorías analíticas red de atención a la salud y género.

Resultados

Los temas fueron potencialidades para la identificación: experiencia del profesional, acogida, vínculo y escucha atenta del relato de la mujer, hijos y/o vecinos y su comportamiento; reconocer las lesiones; la consulta prenatal, visita domiciliaria. Los límites: silencio, negación/no reconocimiento de la violencia, falta de la denuncia por la mujer; miedo y culpabilidad; el déficit y la falta de preparación del equipo; y el miedo debido a la presencia del agresor.

Conclusiones

Cabe reconocer las potencialidades de la Atención Primaria y promover la calificación de los profesionales para la identificación de la situación entre las quejas (in)visibles, impulsando el enfrentamiento de la violencia.

Palabras clave: Violencia contra la mujer, Actitud del personal de salud, Mujeres maltratadas, Salud de la mujer, Prestación de Atención de Salud

Introduction

Violence against women is a kind violation of human rights that affect women from all over the world,1 presenting a high prevalence and impact on health services. It is defined as every act of violence against women that cause physical, psychological and sexual suffering, as well threats and deprivation of freedom.2 It is permeated and determined by gender issues and has as intrinsic component the divergences between sexes, and it represents the social relations of power and the different roles of men and women.3

It is estimated that 30% of women around the world have experienced physical and/or sexual violence.4 Studies point to the consequences of violence to women's health. As for mental health, they point to psychiatric problems, such as depressive disorders, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, somatoform and personality disorder.5, 6 Also, the use of licit and illicit substances and psychotropic and analgesic medication.4, 7 Sleep-related disorders, improper feeding, body aches, bruises, low self-esteem and panic syndrome are also presented by these women.8

In this context, the health sector has fundamental assignments in the intersectoral response to the violence against women as well the identification the kind of violence, a prerequisite for providing immediate care and conducting referrals to specialized services.9 So, it is important that attention to women's health in situation of violence occur in the Health Care Network (HCN), which is a network of organizations that provides or makes arrangements to offer equitable and integral health services to a specific population.10

In the context of the HCN, Primary Health Care (PHC) stands out for its role within this network which is to take over the communication center, organizing and rearranging flow and counter flow of users, products and information in order to enable a quality care and comprehensive care to users,10 mainly to women in a situation of violence. In the PHC, professionals have the possibility of identifying and confronting violence against women.11 This is especially true because health professionals are usually the first sought when they experience a situation of violence.12

Thus, this study aimed to know the potentiality and limitations for identifying situations of violence against women by PHC professionals.

Participants and methods

Design, location and period: Exploratory and descriptive study with a qualitative approach developed in three Family Health Strategy (FHS) units and one Basic Health Unit (BHU) of a municipality of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, in the period of April–July of 2015.

Sample and participants: The participants in this sample were 21 health professionals of the BHU and FHS teams (Table 1). The inclusion criterion consisted of being a professional health worker of these services and the exclusion criterion was being absent from work by any kind license during the period of data production.

Table 1.

Description of participants.

| Identification | Role (profession) at the BHU/FHS | Age (years) | Level of education | Time (years) at the BHU/FHS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 (P1) | Nurse | 36 | HE | 3 |

| Participant 2 (P2) | Nursing Technician | 48 | HE | 13 |

| Participant 3 (P3) | Nursing Technician | 54 | TE | 12 |

| Participant 4 (P4) | Nurse | 26 | Post-graduation (Master) | 1.10 months |

| Participant 5 (P5) | Nursing Technician | 37 | TE | 10 months |

| Participant 6 (P6) | Nursing Technician | 31 | TE | 12 |

| Participant 7 (P7) | Doctor | 66 | Specialist | 18 |

| Participant 8 (P8) | Nurse | 48 | Specialist | 6 |

| Participant 9 (P9) | Nurse | 27 | Specialist | 8 months |

| Participant 10 (P10) | Doctor | 29 | HE | 2 months |

| Participant 11 (P11) | Community Health Agent | 41 | HS | 9 |

| Participant 12 (P12) | Nurse | 40 | HE | 2 months |

| Participant 13 (P13) | Community Health Agent | 43 | HS | 6 |

| Participant 14 (P14) | Community Health Agent | 36 | HS | 5 |

| Participant 15 (P15) | Community Health Agent | 45 | HS | 10 |

| Participant 16 (P16) | Nursing Technician | 37 | TE | 3 months |

| Participant 17 (P17) | Community Health Agent | 43 | HS | 12 |

| Participant 18 (P18) | Nursing Technician | 31 | TE | 3 months |

| Participant 19 (P19) | Community Health Agent | 36 | TE | 6 |

| Participant 20 (P20) | Doctor | 34 | HE | 1 |

| Participant 21 (P21) | Community Health Agent | 32 | HE | 4.3 months |

Note: FHS, family health strategy; BHU, basic health unit; HE, higher education; TE, technician; HS, high school.

Data collection and analysis: Individual semi-structured interviews recorded in MP3 (audio), upon agreement of participants, were used for data generation. A script addressing sociodemographic and training data, the potentialities and limitations for the identification of situations of violence based on the gender perspective, was used. The interview was finished based on the saturation criterion.13 The data were systematized and analyzed through the content analysis technique proposed by Minayo,13 as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Data analysis process.

| Pre-analysis | Literal transcription of the data obtained in the semi-structured interviews using a text editor, what was done by the same researcher who conducted the interviews in order to guarantee the fidelity of the transcription. Listening to the records and quick reading, comprising the first contact with the material obtained in the interviews with creation of the initial impressions about this theme. Sequence of exhaustive readings, from which the excerpts of the participants’ speeches were highlighted with markers of different colors based on similar ideas in the content of the interviews. This step allowed gathering the material, which was submitted to a deeper analysis. |

| Material exploration | Separation of information shared in the content of the different lines transcribed, by means of the enumeration of Nuclei of Meaning. The latter are words, phrases and expressions that give meaning to the content of lines and support the creation of these categories. Grouping of the Nuclei of Meaning for the creation of two thematic categories. |

| Treatment and interpretation of results obtained | Proposition of inferences and interpretation of results according to the objective of this study, having as analytic categories the care network for health and gender. |

The study adopted as theoretical reference the Health Care Network, due to its guidelines and the possibility to offering quality health services to a specific population, which in this study are women in situation of violence. The results were analyzed according to the analytical categories network care for health and gender.

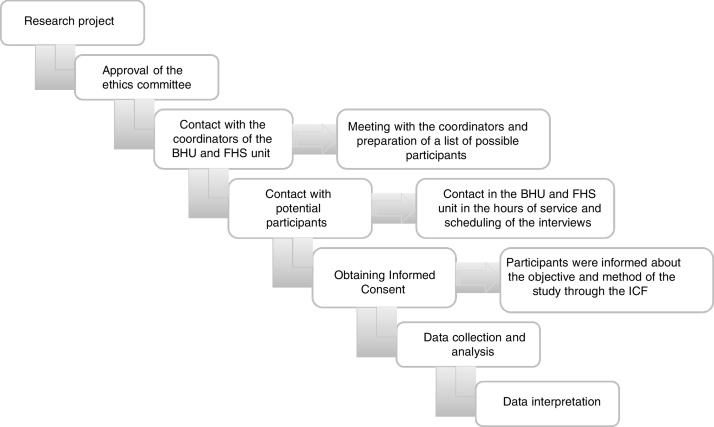

The participants were informed about the objectives and methods of the study through the Informed Consent Form. Those who agreed to participate signed two copies of this term. Participants were identified using the letter P referring to professional, followed by ordinal numbers according to the order of interviews (e.g.: P1, P2, …, P21). The study was approved by the Committee of Ethics on Research with Human Subjects of the Federal University of Santa Maria, Opinion no. 928.490. The recommendations of Resolution no. 466/2012 which regulates studies with humans in Brazil were followed.

General scheme of the study.

Results and discussion

Potential to identify situations of violence against women

In this category, several structural elements of health care in the network emerged in the speech of participants, according to the illustrations that follow (Table 3).

Table 3.

Thematic category 1 and testimony of participants.

| Category 1 | |

|---|---|

| Embracement | We identify more of those situations of violence against women at embracement [...] P1. |

| Active listening | They came here in the health unit shaken, nervous, tearful. I like to identify them when they arrive with high blood pressure. [...] So, you have a conversation with them: ‘Do you take your medicine?’ So, she replied: ‘I take my medicines.’ Then she starts to get a little choked up: ‘My husband drinks, I did not sleep with him tonight’. |

| Bond | Have a bond, because when you create a bond, they will tell you that they are suffering some kind of aggression. P9. |

| Spontaneous reporting | When the woman speaks by herself (without necessity to make questions) P7. |

| Behavior observation | Nursing is privileged work because the person does not need to verbalize that she is suffering violence. The victim has a posture of her own, suffered, she does not look you in your eyes, head down [...] P16. |

| Professional experience | We identify by the time of work. Sometimes they say, ‘I fall’. “Did you fall and get the black eye?” I identify the real story, by the time of work. P2. |

| Injury observation | There are those people we can identify that are not telling the truth. [...] For example: A bite on the body, although the battered person does not have the lower dentition. So, we do not believe in this history [...] P5. What can help me to identify is what I see in the person (referring to injuries). P8. |

| Prenatal consultation | At the prenatal consultation I do not ask about violence [...] I asked: ‘How is your relationship with your husband? And with your children?’ That is a kind of question I ask. The relationship itself. But, not in relation to violence [...] P4. |

| Home visit | We do a home visit. Sometimes, when we get there, the woman has a facial injury [...] P12. |

| Children and/or neighbors reports | I identified because one of the children said: ‘Is not truth mother that dad took the knife to kill you?’ The neighbor said: ‘In that house the man hits her. Sometimes there are screams’. There is a lot of complaint from the community. P12. |

The embracement is pointed out by APS professionals as the main way to identify situations of violence against women. In this sense, the situation of violence requires the professional skills of this host, which implies qualified, sensitive and empathetic assistance, free from blame, so that the woman feels safe to report the violence experienced. It has a view to overcoming the model of attention based on the knowledge and technologies of medical practice, aiming to attend to health needs in an integral way,14 especially in dealing with problems of a multifaceted and complex nature such as violence against women, marked by gender stereotypes.

Behavior observation of the users and the active listening were also pointed out by the professionals and perpass the analysis of information, when women speak spontaneously or when they show objective signs of physical violence experienced. But, mainly the analysis of the non-verbal manifestations, since the majority of the women in these situations behaves in a different way, emphasizing the little verbalization.

The fact that a large number of women in situations of violence show a singular behavior leads the professionals to be suspicious of violence. Thus, during procedures such as blood pressure measurement, it is possible to create an atmosphere for the woman to report the violence. For this, professionals must listen to her carefully, showing interest and respect for her, transmitting to the woman the certainty that she is being heard and understood in her singularity. From such treatments, women tend to trust the health professional and report the situation of violence, so at this moment, the professional have the possibility of developing actions with this woman to confront violence. It is important to emphasize that through the trust placed in the professional, a bond is created, which in turn broadens the dialog between the woman who experience violence and professionals, making attendance and follow-ups faster and more effective,15 within the scope of HCN.

Likewise, the women spontaneous report about violence experienced favors the interventions and referrals of health professionals.16 However, the taboos that are surrounding this problem favors the silence of women, professionals should employ strategies to stimulate reporting, such as building a relationship of trust and bonding, and the development of active listening.

The professional experience also helps the recognition of violence situations. Because they have been working for some time in the APS service, professionals have more experience and they know the daily lives of women and their families. This situation is understood after some experienced in the field, providing support to professionals for the identification of violence, and it is allowing them to become essential for ascertaining the suspicions of violence against women, even if the evidence is unclear.17 Health professionals from APS can identify the situation of violence faster, because of the large service coverage and also the approach to women.18

Another potentiality refers to the observation of injuries in the female human body. Those injuries have particularities, because they are part of a context whose report does not fit with the type of injury. The emphasis on injuries is associated with the visibility of violence for health professionals, which corroborates with another study in which the assistance practiced by professionals to the women in situations of violence is primarily directed at the treatment of injuries.19 Physical marks are visible (burns, fractures and others) that are treated as punctual demands by professionals.16, 17 This reinforces the urgency to overcome the technical training that prevails in training and qualification courses in the health area, considering as content the violence against woman and the gender social category.

There are also different moments of the care process in which health professionals have the possibility to identify violence situations, among which they were mentioned, prenatal consultation and home visits. At prenatal consultations, although professionals do not directly question women about violence, they discuss the relationship they have with their husband and/or partner and their children. These experiences indicate the prenatal consultation as a potent space to identify violence against women.20 This kind of conduct is in accordance with guidance that mentions the investigation of the conflicts existence in the family relationship as a way to identify situations of violence in the gestational period.21

At home visits, the professional, when entering the home of the female, can perceive possible manifestations of violence, by observing physical injuries, or by the woman, the children and/or partners behavior. On that occasion, professionals are able to detect signs and manifestations of different types of violence, and to approach users to report the situation of violence.22 They have also the possibility of finding children and/or neighbors who may report the situation. Because, children often witness situations of violence against their mother, while neighbors may witness or hear something that characterizes a situation of violence. Regarding this aspect, a study showed that FHS professionals report that identification occurred mainly through the observation of signs, by the reports of women or of people close to them.20

Limitations to identify situations of violence against women

In this category, several elements that compose issues related to violence against women from the gender perspective, as following illustrations (Table 4).

Table 4.

Thematic category 2 and participants’ testimonials.

| Category 2 | |

|---|---|

| Denial of the situation of violence | When it comes to this issue (violence) people do not talk much about themselves [...] is always the neighbor. P1 |

| Non-recognition of violence | I believe that the majority of the population, when they speak of violence, they think that it is physical aggression [...] and that many women are raped daily, verbally and morally and they can’t detect this violence. P4. |

| Fear and blame | They (women) do not speak out of fear of coming home and getting hurt again [...] I said, ‘go there and complain because he drinks and beats the kids up’. And she said, ‘if I do that I may come home and he would kill me’. P3. |

| Flaws on the part of professionals | In a basic unit that serves more than 30,000 people, there is less human resources than there should be. You can’t know the reality of these people. You know what they tell you. P4. I have to do things fast, I do not have time to identify if the patient does not tell me. P20. |

| Unpreparedness health team | These issues of violence end up getting in the background because other issues are more urgent: prenatal consultation, childcare consultation. Thus, issues of violence, which are related to health, but are more of a social nature, end up left in the background. Even because they are difficult to work [...] it is mostly about this biomedical, curative issue. We go there, do the procedure. Treat the injury, treat the pain. P4. |

| Presence of the aggressor | The girl came here with him (her companion... and wanted an excuse note not go to work). She said she fell, but we know she didn’t. P18. |

| Fear of professionals | We are very vulnerable because we have no police here. What if we notify and they suspect of us? They (aggressors) can come here and shoot us. P4. |

The participants mention aspects related to the concealment of situations of violence, evidenced by the woman's non-recognition of the situation she is experiencing, the visibility of physical violence and the invisibility of psychological or emotional violence. They also mentioned the possibility of the woman to be hiding and/or denying the situations lived, which results from fear of reporting, denouncing the aggressor, or even because they feel guilty. These aspects arise from the social construction of gender in which women occupy a position of inferiority in relation to men in the context of relationships, besides the fact that the use of violence by men is taken as natural.

In this scenario, professionals can develop activities to promote women's health in an individual or collective scope, informing them about the types of violence and their possibilities of coping. They must also reinforce the notion that violence should not be trivialized.23 In direct care, adopting an attitude of willingness and empathic, respectful and nonjudgmental openness to break up the silence is something that minimizes the fear and feeling of guilt of women. With regard to silence, a study proposes that this represents one of the greatest barriers to the recognition and confrontation of violence against women, with the consequence of recurrent aggression.16

Concerning the women's fear of denouncing the aggressor, evidence points to the following reasons: concern with children; fear of retaliation on the part of the aggressor; belief that the aggression will no longer be repeated; belief that the aggressor will not be punished; and shame of the aggression suffered.24

Other aspects that hinder the identification of violence are related to flaws and lack of preparation on the part of the health team to provide care to the user and her family in their respective areas of training and performance. In spite of the shortage of health professionals in the teams, it is necessary that superficial consultations in which the professionals do not follow-up the women or the possibilities of dialog about the problem experienced are not possible must be eliminated.25 In this respect, a study revealed that health professionals should provide adequate time to approach the subject with the victim.26 This space is fundamental, whether in medical and nursing consultations, in home visits, or during the development of procedures.

The unpreparedness of the health team to identify and address the issue of violence can be explained by professional training that prioritizes curative and biomedical aspects, considering that most health professionals did not have contact with the theme during undergraduate training.27 Therefore, it is necessary to include violence against women in the training of health professionals, so as to sensitize them and enable them to act in the face of this problem.

According to one of the health professionals interviewed, violence against women ends up left in the background because they believe that it is also a social issue for which they are not prepared to intervene. These results corroborate a research that points out that professionals working in health services have limitations to deal with problems such as violence because of the essentially social or personal nature of the problem.28 Thus, it is fundamental that health professionals include the demands for care resulting from violence as the object of their actions by understanding that the breadth or complexity of the issue does not exempt professionals from helping women in situation of violence within the health care network.

The presence of the aggressor in the care setting was also reported by professionals as a hindrance for the identification of violence in PHC. This inhibits the reporting of women, the action of professionals and notification to authorities, often due to fear also felt by professionals. It is important to create strategies that guarantee the privacy of women: when in the unit, it should be requested that the possible aggressor leave the woman and the professional alone; when in the home, an appointment in the unit should be scheduled because, in general, men who practice violence seek to exercise control upon the actions of their female partners. As an example, in prenatal consultations, the user will hardly report the situation of violence in the presence of the aggressor.25 As for the fear that the professionals feel, this is related to the possibility of retaliation by the aggressor, which is one of the determining reasons for not doing the notification in their areas of performance.29

Conclusion

The results give evidence of the need for professionals to recognize in their work attitudes in PHC their potentialities for the identification of violence among the (in)visible complaints of women, impelling the confrontation. It is urgent to include the theme in the training of health professionals and in their qualification through continuing education in order to qualify the actions that make it possible to detect cases of violence. This will imply in a clinical practice grounded, especially, in embracement and bond as possibilities to break with the silence that pervades situations of violence.

The limitations of the present study are typical of descriptive qualitative studies, particularly the fact that the study was developed in a local level, in some PHC services in just one municipality, making it difficult to generalize the findings. However, their results contribute with subsidies to (re)think the actions of PHC professionals in order to identify situations of violence experienced by women. Furthermore, the study presents valid findings for daily clinical practice and public policies in the perspective of care network to health and genders, seeking to confront and prevent new situations of violence. As implications, intervention studies are recommended to fill gaps and promote strategies to assist in this identification.

What is known on the topic

-

-

Violence has several consequences for the health of women who experience it and the professionals involved in Primary Health Care (PHC) play a fundamental role in identifying and addressing this problem.

-

-

Most of the time, they are the first to be sought by women with various complaints or (in)visible evidence of violence. In public policies, PHC is recognized worldwide as the preferred gateway to the Health Care Network.

What this study contributes

-

-

PHC has the potential to identify situations of violence against women through embracement; active listening; bonding; spontaneous reporting and observation of woman's behavior; professional experience; and actions such as prenatal consultation; home visits in which the story of children and neighbors arise.

-

-

It also has limitations such as denial and non-recognition of violence; fear and guilt; flaws on the part of professionals; unpreparedness and fear of professionals, sometimes due to the presence of the aggressor in the unit.

-

-

Given the potential of PHC to identify situations of violence against women, the results of this study can be used for daily clinical practice and public policies in the perspective of the health care network, seeking to confront and prevent new situations of violence.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Ellsberg M., Arango D.J., Morton M., Gennari F., Kiplesund S., Contreras M. Prevention of violence against women and girls: what does the evidence say? Lancet. 2015;385:1555–1566. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61703-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naciones Unidas Organización (ONU) ONU; 2006. Estudio a fondo sobre todas las formas de violencia contra la mujer. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott J. Gênero: uma categoria útil de análise histórica. Educação Realidade. 1995;20:71–99. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO; Suiça: 2013. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of sexual violence from intimate partners and non-partners. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Satyanarayana V.A., Chandra P.S., Vaddiparti K. Mental health consequences of violence against women and girls. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:350–356. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salom C.L., Williams G.M., Najman J.M., Alati R. Substance use and mental health disorders are linked to different forms of intimate partner violence victimization. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;151:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simmons S.B., Knight K.E., Menard S. Consequences of intimate partner violence on substance use and depression for women and men. J Fam Viol. 2015;30:351–361. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Netto L.A., Moura M.A.V., Queiroz A.B.A., Tyrrell M.A.R., Bravo M.M.P. Violência contra a mulher e suas consequências. Acta paul Enferm. 2014;27:458–464. [Google Scholar]

- 9.García-Moreno C., Hegarty K., d’Oliveira A.F.L., Koziol-McLain J., Colombini M., Feder G. The health systems response to violence against women. Lancet. 2015;385:1567–1579. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Organización Panamericana de Salud (OPAS) OPAS; Washington: 2010. Redes Integradas de Servicios de Salud. Conceptos, opciones de política y hoja de ruta para su implementación en las Américas. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodríguez-Blanes G.M., Vives-Cases C., Miralles-Bueno J.J., Sebastián M.S., Goicolea S. Detección de violencia del companero íntimo en atención primaria de salud y sus factores asociados. Gac Sanit [Internet] 2017;31:410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2016.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Organización Panamericana de la Salud (OPAS) OPAS; Washington: 2014. Resumen: Respuesta a la violencia de pareja y a la violencia sexual contra las mujeres. Directrices de la OMS para la práctica clínica y las políticas. [Internet] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minayo M.C.S. 14 ed. Hucitec; São Paulo: 2014. O desafio do conhecimento: pesquisa qualitativa em saúde. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos D.S., Mishima S.M., Merhy E.E. Processo de trabalho na Estratégia de Saúde da Família: potencialidades da subjetividade do cuidado para reconfiguração do modelo de atenção. Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2018;23:861–870. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232018233.03102016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guerrero P., Mello A.L.S.F., Andrade S.R., Erdmann A.L. User embracement as a good practice in primary health care. Texto Context Enferm. 2013;22:132–140. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nascimento E.F.G.A., Ribeiro A.P., Souza E.R. Perceptions and practices of Angolan health care professionals concerning intimate partner violence against women. Cad Saude Publ. 2014;30:1229–1238. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00103613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes N.P., Garcia T.C.S., Conceição C.R., Sampaio P.O., Almeida V.C., Paixão G.P.N. Violência conjugal: elementos que favorecem o reconhecimento do agravo. Saúde Debate. 2012;36:514–522. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Visentin F., Vieira L.B., Trevisan I., Lorenzini E., Silva E.F. Women's primary care from nursing in situations of gender violence. Invest Educ Enferm. 2015;33:556–564. doi: 10.17533/udea.iee.v33n3a20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva E.B., Padoin S.M.M., Vianna L.A.C. Violence against women and care practice from the perception of the health professionals. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2015;24:229–237. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guedes R.N., Fonseca R.M.G.S., Egry E.Y. Evaluative limits and possibilities in the family health strategy for gender-based violence. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2013;47:304–311. doi: 10.1590/s0080-62342013000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministério da Saúde . Ministério da Saúde; Brasília: 2012. Gestação de alto risco: manual técnico. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva E.B., Padoin S.M.M., Vianna L.A.C. Violence against women: the limits and potentialities of care practice. Acta Paul Enferm. 2013;26:608–613. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arboit J., Padoin S.M.M., Vieira L.B., Paula C.C., Costa M.C., Cortes L.F. Health care for women in situations of violence: discoordination of network professionals. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2017;51:e03207. doi: 10.1590/S1980-220X2016113303207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministério da Saúde . Senado Federal; Brasília: 2015. Violência doméstica e familiar contra a mulher. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kiss L.B., Schraiber L.B. Temas médico-sociais e a intervenção em saúde: a violência contra mulheres no discurso dos profissionais. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2011;16:1943–1952. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232011000300028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Usta J., Antoun J., Ambuel B., Khawaja M. Involvement of the health care system in domestic violence: what does women want? Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:213–220. doi: 10.1370/afm.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliveira C.C., Almeida M.A.S., Morita I. Violência e saúde: concepções de profissionais de uma Unidade Básica de Saúde. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2011;35:412–420. [Google Scholar]

- 28.D‟Oliveira A.F.P.L., Scharaiber L.B. Mulheres em situação de violência: entre rotas críticas e redes intersetoriais de atenção. Rev Med. 2013;92:134–140. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kind L., Orsini M.L.P., Nepomuceno V., Gonçalves L., Souza G.A., Ferreira M.F.F. Subnotificação e (in)visibilidade da violência contra mulheres na atenção primária à saúde. Cad Saúde Públ. 2013;29:1805–1815. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00096312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]