Abstract

Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease is a progressive and heterogeneous inherited peripheral neuropathy. A myriad of genetic factors have been identified that contribute to the degeneration of motor and sensory axons in a length-dependent manner. Emerging biological themes underlying disease include defects in axonal trafficking, dysfunction in RNA metabolism and protein homeostasis, as well deficits in the cellular stress response. Moreover, genetic contributions to CMT can have overlap with other neuropathies, motor neuron diseases (MNDs) and neurodegenerative disorders. Recent progress in understanding the molecular biology of CMT and overlapping syndromes aids in the search for necessary therapeutic targets.

Keywords: CMT, Genetics, Motor Neuron Disease, Neurodegeneration, Disease Spectrum, Ribosome-Associated Quality Control

Introduction

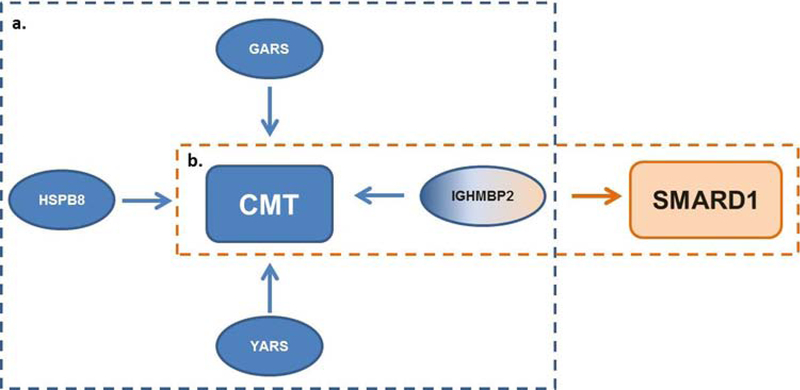

In the mid to late nineteenth century a premier neurologist, Jean-Martin Charcot, set out to correlate clinical findings in neurological patients with anatomical discoveries in the nervous system using a novel method known as the anatomoclinical method. This method provided comprehensive clinical findings coupled with the pathological changes, allowing for specific disease classification. Charcot defined many neurological disorders, chief among them multiple sclerosis (MS) in 1868, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) in 1869, and Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease in 1886. Although Charcot made great strides in neurology, his work predated modern understandings of inheritance and genetics, and it was not until almost a century later that the first genotype-phenotype correlation was made in CMT (PMP22) in 1991 and ALS (SOD1) in 1993 (Lupski et al., 1991, Timmerman et al., 1992a; Rosen et al., 1993). With the advent of precision genetics, we are now able to examine a disease from its three main faces: clinical presentation, pathological features, and underlying genetics. Variations in different genes can phenotypically converge onto the same clinical classification or disease category; an excellent example of this is Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (Fig. 1a). Conversely, variants within the same gene can diverge pathogenically and give rise to a spectrum of diseases (Fig. 1b). Among those with clinical and genetic heterogeneity are inherited peripheral neuropathies (IPNs), a group of diseases including CMT and hereditary motor neuropathy (HMN).

Figure 1.

Schematic showing that a. genetic contributions can converge onto a similar clinical phenotype as well as a b. genetic contribution presenting with diverging clinical presentation.

Charcot-Marie-Tooth is characterized by progressive muscular atrophy and loss of sensation in a length-dependent manner and is the most common IPN, with an estimated 1 in 2,500 individuals affected (Skre, 1974). CMT is further clinically subdivided into Types 1, 2, and intermediate. Classically, Type 1 CMTs are demyelinating neuropathies with decreased nerve conduction velocities (NCV), while Type 2 CMTs are axonal neuropathies with normal or near-normal NCVs. More recently, intermediate forms have been recognized with clinical characteristics of both demyelination and axonal degeneration. While CMTs are defined as having both distal sensory and motor involvement, other IPNs can be predominantly motor (hereditary motor neuropathy, HMN) or predominantly sensory (hereditary sensory neuropathy, HSN) (Rossor et al., 2015).

Recent work defining the genetic underpinnings of CMT suggests significant overlap in genes that may also be contributing to motor neuron diseases (MND) and other neurodegenerative diseases (Table 1). Historically, CMT and MNDs have been defined and diagnosed through clinical presentation, but newly-available genetic information can shed new light on these diseases and reshape our understanding of their classification. Genetic factors contributing to one disease presentation in one patient may have a slightly different presentation in another. CMT primarily impacts the most distal axons of a patient, whereas MNDs generally have upper and/or lower motor neuron degeneration as well as central involvement, there can be considerable overlap in the presentation of more severe CMTs and more mild or slowly-progressing MNDs. Common genetic MNDs that will be discussed in this review include: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) a later-onset MND resulting in progressive paralysis and mortality, as well hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) sometimes referred to as spastic paraplegia (SPG) an inherited MND with bilateral lower-extremity spasticity and weakness. HSP can be defined as uncomplicated (pure) or can be classified as complicated, which is characterized as having additional neurologic findings including, but not limited to, ataxia, intellectual disability, or peripheral neuropathy.

Table 1.

The Broad Genetic Overlap of CMT, MND and Neurodegenerative Diseases.

| Gene Name | Disease-Association | Inheritance | Function | OMIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMT2E | Dominant | 607684 | ||

| NEFL | CMT1F | Dom/Rec | Neuronal cytoskeleton | 607734 |

| CMT, dominant intermediate G | Dominant | 617882 | ||

| NEFH | CMT2CC | Dominant | Neuronal cytoskeleton | 616924 |

| ALS | Dom/Rec | 105400 | ||

| DYNC1H1 | CMT2OMRD13 | Dominant | 614228 | |

| Dominant | Retrograde transport | 614563 | ||

| SMALED1 | Dominant | 158600 | ||

| DCTN1 | CMT2C | Dominant | 607641 | |

| Perry syndrome | Dominant | Retrograde transport | 168605 | |

| ALS | Dom/Rec | 105400 | ||

| CMT2 | Dominant | |||

| KIF5A | SPG10 | Dominant | Anterograde transport | 604187 |

| ALS | Dominant | 617921 | ||

| NEIMY | Dominant | 617235 | ||

| HSN2C | Recessive | 614213 | ||

| KIF1A | SPG30 | Dom/Rec | Anterograde transport | 610357 |

| MRD9 | Dominant | 614255 | ||

| RTT | Recessive | |||

| CMT4J | Recessive | 611228 | ||

| FIG4 | ALS | Dominant | Vesicle trafficking | 612577 |

| Yunis-Varon syndrome | Recessive | 216340 | ||

| BTOP | Recessive | 612691 | ||

| SPG11 | ALS | Recessive | 616668 | |

| Spastic paraplegia 11 | Recessive | Vesicle trafficking | 602099 | |

| CMT2X | Recessive | 604360 | ||

| IGHMBP2 | SMARD1 | Recessive | RNA/DNA Helicase | 604320 |

| CMT2S | Recessive | 616155 | ||

| CLP1 | PCH10 has lPN component | Recessive | Splicing of intron containing tRNA | 615803 |

| GARS | CMT2D | Dominant | ||

| HMN5A | Dominant | Cytoplasmic and mitochondrial tRNA synthetase | 601472 | |

| blubar ALS | Dominant | 600794 | ||

| AARS | CMT2N | Dominant | Cytoplasmic tRNA synthetase | 616339 |

| MARS | CMT2U | Dominant | Cytoplasmic tRNA synthetase | 616280 |

| HARS | CMT2W | Dominant | Cytoplasmic tRNA synthetase | 616625 |

| KARS | CMTIB | Recessive | Cytoplasmic tRNA synthetase | 613641 |

| YARS | CMT-DIC | Dominant | Cytoplasmic and mitochondrial tRNA synthetase | 608323 |

| GTPBP2 | JABELS | Recessive | Ribosome recycling factor | 617988 |

| NEMF | ID w/hypotonia | Recessive | CATylation Ltn1 recruitment | 608378 |

| LTN1 | Mouse model: locomotor abnormalities neurodegeneration | Recessive | E3 ubiquitin ligase, degradation of aberrant nascent chains | 613083 |

| VCP | CMT2Y | Dominant | Protein degradation | 616687 |

| ALS14 | Dominant | 613954 | ||

| IBMPFD | Dominant | 167320 | ||

| HSPB1 | CMT2F | Dominant | Stress-activated kinase | 606595 |

| dHMN2B | Dominant | 608634 | ||

| HSPB3 | dHMN2C | Dominant | Stress-activated kinase | 613376 |

| CMT2 | Dominant | |||

| HSPB8 | CMT2L | Dominant | Stress-activated kinase, chaperone activity | 608673 |

| dHMN2A | Dominant | 158590 | ||

| DNAJB2 | dSMA5 | Recessive | ||

| dHMN | Recessive | Stress-activated kinase, chaperone activity | 614881 | |

| CMT2-like | Recessive | 614881 |

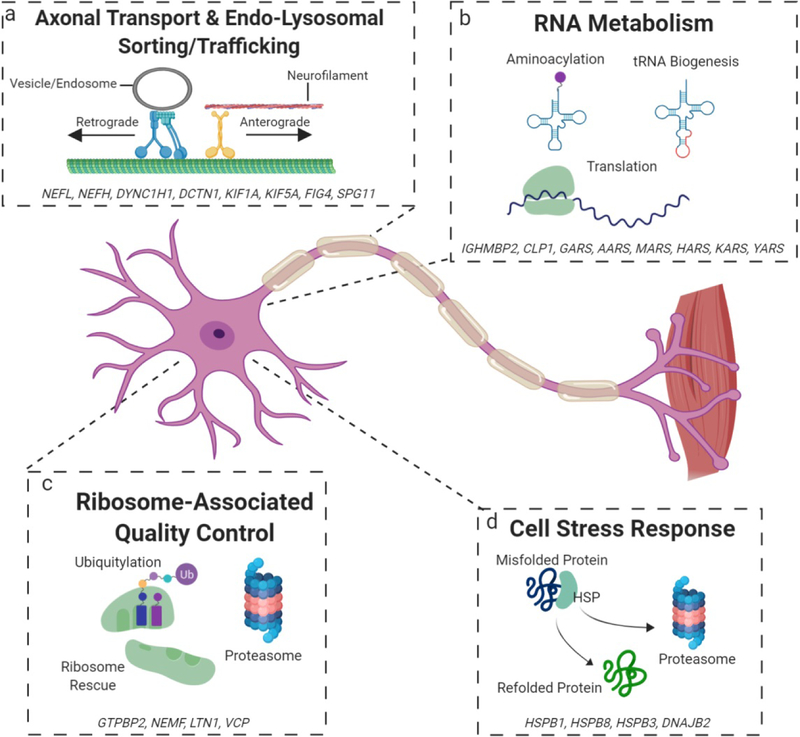

Here we will consider in depth the clinical and genetic features of CMT, as well as a spectrum of MNDs and other neurodegenerative diseases that share overlapping genetic contributions. We highlight emerging themes associated with pathogenic contributions to this spectrum, including disrupted axonal transport (Fig. 2a), dysfunction in RNA metabolism (Fig. 2b), the ribosome-associated quality control pathway (Fig. 2c), and cell stress response (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2. Mechanisms of disease implicated in CMT and a broader neurodegenerative spectrum.

a. Variants in genes involved in the endo-lysosomal sorting/trafficking, cytoskeleton, and axonal transport can disturb cytoskeletal integrity and impair transportation, limiting the movement of necessary organelles between the cell body and distal portions. b. Disruptions in proteins involved in the processing (CLP1) and charging (AARs proteins) of tRNAs, as well as others can impair translation and RNA metabolism, which slows a high translational demand. Additionally, neomorphic activities of AARs proteins can disrupt neuronal homeostasis. c. Mutations in proteins involved in the rescue and recycling of stalled ribosomes can give rise to potentially toxic polypeptides and disrupts the sensitive cellular economy of neurons and distal axons. d. Impairments in heat shock proteins, chaperones for potentially toxic misfolded proteins, can lead to toxic aggregates that further sequester more heat shock proteins, impairing the appropriate cell stress response.

1. Axonal Transport & Endo-Lysosomal Sorting/Trafficking

Endo-Lysosomal sorting and trafficking as well as axonal transport are both critical for axon growth, maintenance, and signaling (Cosker and Segal, 2014; Maday et al., 2014; Kalani and Tyagi, 2015; Mestres and Sung, 2017), so it is not surprising that mutations in the various genes associated with these processes have been tied to a wide variety of neurodegenerative diseases (De Vos et al., 2008; Hinckelmann et al., 2013; Millecamps and Julien, 2013; Neefjes and van der Kant, 2014; Prior et al., 2017; Burk and Pasterkamp, 2019; Vagnozzi and Praticò, 2019). In this section, we will take a closer look at a few of these genes that encode for proteins that make up the axon cytoskeleton, molecular motors, and vesicle trafficking and are implicated in a range of neuropathies (Fig. 2a) (Table 1).

1.1. NEFL

The NEFL gene encodes the neurofilament light chain protein which forms a type IV intermediate filament and plays a major role in the neuronal cytoskeleton (Agrawal et al., 2014). Mutations in this gene are associated with a variety of different CMT subtypes including CMTDIG (dominant intermediate type G) (Züchner et al., 2004), CMT1F (Jordanova et al., 2003), and CMT2E (Georgiou et al., 2002).

CMTDIG is an intermediate, but variable, disease with phenotype onset typically before 20 years of age and a slow progression that results in a spectrum of severity from progressive gait instability, to patients becoming wheelchair bound (Züchner et al., 2004; Berciano et al., 2015). It has been speculated that the demyelinating symptoms observed in patients may actually be secondary to the axon loss (Züchner et al., 2004; Berciano et al., 2017). Patients with autosomal dominant CMT1F typically present between 1–13 years of age with reduced nerve conduction velocity, sensory defects, and pathology consistent with a demyelinating neuropathy (Jordanova et al., 2003; Abe et al., 2009; Yum et al., 2009). One group speculated that a missense mutation in NEFL can also cause a recessive form of CMT1F (Abe et al., 2009) which was later supported by a study using patient-specific derived neurons in culture (Sainio et al., 2018). Dominant CMT2E is typically slower and less severe with onset starting in the 20s or later and pathology showing signs of giant axons indicating an axonopathy (Georgiou et al., 2002; Fabrizi et al., 2004; Miltenberger-Miltenyi et al., 2007).

Cell models carrying CMT2E and CMT1F mutations show that transport and assembly of neurofilament proteins are disrupted causing aggregation (Brownlees et al., 2002; Gentil et al., 2013; Saporta et al., 2015), which may provide a common therapeutic target and is a common feature in many other neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS. The cause of the variability seen in NEFL patients is currently unknown, but one paper notes that mutations in the head domain may slow nerve conduction velocities more than mutations in other regions of the gene (Miltenberger-Miltenyi et al., 2007).

1.2. NEFH

The NEFH gene encodes the heavy chain neurofilament protein which is a major component of the cytoskeleton in large myelinated axons (Elder et al., 1998). A NEFH-null mouse model showed that NEFH protein is not crucial for development but it does plays a critical role in the survival of mature motor and sensory axons (Rao et al., 1998). Overexpression of NEFH results in degeneration of motor neurons (Collard et al., 1995). Mutations in this gene have been associated with both mild ALS and CMT2CC.

While rare, most ALS-associated mutations identified in NEFH change transcription patterns resulting in one long and one short transcript that appear to encode proteins that assemble normally with other neurofilament subunits but may have altered interactions with other cytoskeletal elements (Figlewicz et al., 1994; Tomkins et al., 1998; Al-Chalabi et al., 1999). The dominant mutations in CMT2CC patients produce a frameshift in the last exon of the gene that causes the polymerase to read through the stop codon and add additional amino acids including a cryptic amyloidogenic element (Rebelo et al., 2016; Jacquier et al., 2017). Studies have also shown that the inclusion of these additional elements make the mutant NEFH highly likely to form protein aggregates (Rebelo et al., 2016).

While the mechanism of each of the mutations is slightly different, NEFH protein aggregation occurs in the dominant forms of both NEFH–related ALS and CMT2CC. The age of symptom onset of CMT2CC patients varies highly ranging from the first few years of life to over 50 years old. Aside from heterogeneity between alleles, intrafamilial variability is also observed suggesting that this mutation has that ability to be modulated by genetic background (Rebelo et al., 2016).

1.3. DYNC1H1

The DYNC1H1 gene codes for dynein heavy chain which assembles with multiple other subunits to form a molecular motor that uses ATP retrograde transport down toward the microtubule minus-ends. In axons, microtubules have uniform “plus-end out” polarity, so dynein is primarily responsible for retrograde transport in this cellular compartment. Mutations in this gene have been associated dominantly with CMT2O (Weedon et al., 2011), lower extremity-predominant spinal muscular atrophy-1 (SMALED1) (Harms et al., 2010, 2012; Tsurusaki et al., 2012), and mental retardation 13 (MRD13) (Vissers et al., 2010). Mouse models have validated these associations showing signs of both a neuropathy (Hafezparast et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2007), as well as neuronal migration defects in the cortex (Ori-McKenney and Vallee, 2011).

Symptom onset for dominant CMT2O appears during childhood before progressing slowly with both motor and sensory impairment as well as indications of learning impairment (Weedon et al., 2011). Interestingly, most of the MRD13 patients also experienced CMT-like symptoms, early-onset MR, seizures, and brain scans of these patients showed cortical malformations, likely due to neuronal migration defects (Vissers et al., 2010; Willemsen et al., 2012; Poirier et al., 2013; Jamuar et al., 2014). SMALED1 is a dominant form of Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) with clinical onset typically in early childhood with predominant paralysis in the lower extremities (Harms et al., 2010, 2012; Tsurusaki et al., 2012). While many patients exhibit severe early phenotypes, one patient’s symptoms were so mild that she was not genetically diagnosed until her children were diagnosed, suggesting that other genetic factors may contribute to susceptibility (Tsurusaki et al., 2012). New work has also shown that some SMALED1 patients may present with a congenital myopathy (Beecroft et al., 2017).

The overlap and variability in phenotype severity illustrate that this may really be a spectrum of overlapping diseases with the potential to be modified by other genetic factors (Lipka et al., 2015). The differences in severity related to DYNC1H1 have been mechanistically associated with both the methylation state of the gene at exon 37 (Maretina et al., 2019) and the change in processivity of dynein to move long distances through its binding to both dynactin and the BICD2 cargo adaptor (Hoang et al., 2017) with the latter possibly explaining the dominance seen in these diseases.

1.4. DCTN1

The DCTN1 gene produces the p150(Glued) protein and is the largest subunit of the dynactin complex which binds to both the dynein motor, as well as acting as a cargo adapter (Holzbaur and Tokito, 1996) and is essential for most dynein function (Gauthier et al., 2004; Schroer, 2013). It normally binds directly with both dynein and microtubules through its N-terminus. Additionally, it plays a role in retrograde transport of autophagosomes (Ikenaka et al., 2013). Mutations in this gene have been associated with Perry Syndrome (Perry et al., 1975; Farrer et al., 2009) and distal hereditary motor neuropathy type VIIB (dHMN7B) (Puls et al., 2003; Nam, 2016), as well as ALS (Munch et al., 2004). While these mutations typically result in impairment of axon transport, it is important to note that this is not always the case (Chevalier-Larsen et al., 2008; Lloyd et al., 2012).

Perry syndrome is the most well studied of the DCTN1-associate diseases. Patients experience an onset of depression later in life followed by Parkinson’s and eventually respiratory failure due to defects in brainstem respiratory neurons (Perry et al., 1975, 2012; Caroppo et al., 2014). There is also substantial neuron loss seen in the substantia nigra and TDP43 pathology (Wider et al., 2010). Mutations associated with Perry syndrome act in a dominant manner and all are located in exon 2 within the microtubule binding domain of the protein (Puls et al., 2003; Farrer et al., 2009). Cell-based assays show that the result of these mutations is decreased microtubule binding (Farrer et al., 2009). dHMN7B is an intermediate motor neuron disease with progressive distal paralysis of the face, hands, and vocal cords with weakness of the lower distal limb progressing later (Puls et al., 2003). Histology shows abnormal dynein-dynactin inclusions within the motor neurons (Puls et al., 2005). While the first dHMN7B mutation was identified in exon 2, others have since been identified in other domains of DCTN1 (Hwang et al., 2016; Konno et al., 2017). Symptoms of dHMN7B overlap with CMT, which may account for some patients being initially diagnosed with CMT (Nam, 2016). As for ALS, while there have been DCTN1 mutations identified in ALS patients, a larger study could not find any conclusive association between DCTN1 mutations and ALS, Parkinson’s disease, or frontotemporal lobar degeneration (Vilariño-Güell et al., 2009). The differences in pathology and affected cell types in both Perry syndrome and dHMN7B indicate that they may have different molecular mechanisms.

1.5. KIF5A

The KIF5A gene encodes Kinesin heavy chain isoform 5A which is a neuron-specific member of the kinesin protein family (Niclas et al., 1994). It is involved in trafficking of a variety of cargoes anterogradely within axons (toward microtubule plus-ends) (Okada et al., 1995; Kanai et al., 2004). Mutations in this gene have been associated with a dominant form of neonatal intractable myoclonus (NEIMY) (Duis et al., 2016), ALS (Nicolas et al., 2018), Spastic paraplegia-10 (SPG10) (Reid et al., 2002a), and CMT2 (Crimella et al., 2012).

NEIMY is a severe neurological disorder in which patients experience myoclonic seizures soon after birth, developmental delays, and mitochondrial dysfunction (DaRe et al., 2013; Duis et al., 2016). The mutations that cause NEIMY are all stop-loss mutations that produce a longer protein that is postulated to alter mitochondrial transport (DaRe et al., 2013; Duis et al., 2016; Rydzanicz et al., 2017). All of the dominant loss-of-function mutations identified in ALS patients were either located near exon 26/27 or the C-terminus and resulted in abnormal splicing (Brenner et al., 2018; Nicolas et al., 2018). SPG10 is a variable disease that classically occurs in childhood or early adulthood with spasticity and hyperreflexia of the lower limbs. Some patients also show involvement of upper limbs and sensory defects. In rare cases, there can also be cognitive decline or Parkinson-like symptoms (Goizet et al., 2009; Crimella et al., 2012). Dominant missense mutations in these patients seem to primarily occur in the motor domain of the gene (Reid et al., 2002b; Crimella et al., 2012). There are some SPG10 patients that present with distal sensory and motor defects in the absence of spasticity which is more a CMT2-like phenotype. There are also patients diagnosed with CMT2 that have KIF5A mutations in the motor domain (Goizet et al., 2009; Crimella et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2014; Nam et al., 2018).

SPG10 and CMT2 share not only overlapping phenotypes, but they also share some overlap in mutations (Nam et al., 2018). This is why it is believed that SPG10 and CMT2 patients represent a spectrum (Crimella et al., 2012; Nam et al., 2018) and indicate that the phenotype can potentially be modified. While NEIMY and KIF5A-associated ALS share different mechanisms of disease from each other and SPG10/CMT2, they do share genetic overlap which can make structure/function assignments difficult.

1.6. KIF1A

KIF1A encodes Kinesin family member 1A which is a kinesin heavy chain protein involved in anterograde transport of synaptic vesicles down microtubules in axons (Rivire et al., 2011). Mutations in this gene have been associated with hereditary sensory neuropathy type IIC (HSN2C) (Rivire et al., 2011), spastic paraplegia 30 (SPG30) (Erlich et al., 2011; Klebe et al., 2012; Pennings et al., 2019), mental retardation autosomal dominant 9 (MRD9) (Hamdan et al., 2011; Esmaeeli Nieh et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015), and, very recently, Rett Syndrome (RTT) (Wang et al., 2019). At one point, KIF1A was also thought to be a candidate gene for juvenile-onset ALS4, but mapping studies disproved that theory (Keller et al., 1999).

HSN2C is a recessive sensory neuropathy resulting in distal numbness and weakness with a variable but typically young age of onset, and a subset of HSN2C patients also develop mental deficits more like MRD9 (Rivire et al., 2011). SPG30 has a slowly progressive phenotype onset in the first two decades of life and results in unsteady gait and over responsive reflexes (Erlich et al., 2011). Some patients also eventually develop sensory deficits, and SPG30 can be caused by either recessive or dominant loss-of-function mutations (Erlich et al., 2011; Klebe et al., 2012; Pennings et al., 2019). MRD9 is a dominantly inherited form of mental retardation with varying degrees of spasticity, hypotonia, peripheral neuropathy, and cerebellar atrophy (Hamdan et al., 2011; Esmaeeli Nieh et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015). Recently, one patient with a classical RTT syndrome diagnosis was identified to be compound heterozygous for KIF1A mutations (Wang et al., 2019). She showed signs of delayed development, never achieved independent mobility or the ability speak, and developed classical repetitive behaviors, but more patient data and experiments are needed to see if this association between KIF1A and RTT is causative.

HSN2C patients tend to have truncating mutations where SPG30 patients tend to have missense mutations (Klebe et al., 2012). These missense mutations are commonly found in the motor domain of KIF1A for both forms of SPG30 and MRD9, but some disease associated mutations have been identified outside of this region (Krenn et al., 2017; Pennings et al., 2019). While some mutations slow the transport of synaptic vesicles, several point mutations associated with SPG30 have been shown to produce a hyperactive form of KIF1A (Chiba et al., 2019). While there is some overlap in phenotypes between the various KIF1A-related diseases, the fact that there are both gain and loss-of-function mutations as well as mutations that truncate or alter protein function by either slowing or speeding up transport indicates that the mechanism of disease may not entirely be shared other than altered axon transport and that these diseases are potentially not part of a spectrum.

1.7. SPG11

The SPG11 gene encodes the protein spatacsin. While the exact function of SPG11 is unknown, it has been shown to play a role in anterograde transport, axon maintenance, and lipid turnover (Pérez-Brangulí et al., 2014; Branchu et al., 2017). It has also been shown to localize to axons and dendrites (Branchu et al., 2017). Mutations in this gene have been recessively associated with CMT2X (Montecchiani et al., 2016), autosomal recessive juvenile amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-5 (ALS5) (Hentati et al., 1998; Orlacchio et al., 2010), and spastic paraplegia-11 (SPG11) (Nakamura et al., 1995; Stevanin et al., 2007; Paisan-Ruiz et al., 2008; Guidubaldi et al., 2011; Hinreiner et al., 2016).

CMT2X is a slowly progressive recessive CMT with onset in the first 20 years of life resulting from axonal loss in the distal lower limbs. Almost all of the identified mutations are predicted to produce a non-functional truncated protein (Montecchiani et al., 2016). ALS5 is a recessive and slowly progressive form of ALS with phenotype onset before age 25 due to loss of motor neurons. A majority of the identified mutations implicated in ALS5 are predicted to result in truncated proteins (Orlacchio et al., 2010). SPG11 is a recessive disorder with significant phenotypic variability characterized by spastic movement of the lower limbs, progressive weakness, and a thin corpus callosum (Nakamura et al., 1995). Many patients also experience the development of a sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy and cognitive impairment. SPG11-associated mutations cause a frameshift that is predicted to cause a loss-of-function (Stevanin et al., 2007). There is a strong case for these diseases being modifiable due to the observed phenotypic variability and overlap in clinical features while sharing many of the same mutations (Bauer et al., 2009; Orlacchio et al., 2010; Montecchiani et al., 2016).

1.8. FIG4

The FIG4 gene encodes the Sac3 phosphoinositide phosphatases protein which helps to cleave a phosphate group from phosphoinositides within lysosomal membranes to regulate fission and fusion of vesicles (Sbrissa et al., 2007). Data indicates that Sac3 may also regulate homeostasis of lysosomal membranes in a noncatalytic manner (Bharadwaj et al., 2016), and mutations in FIG4 result in dysfunction in lysosomal storage (Martyn and Li, 2013). Mutations have been associated with CMT4J (Chow et al., 2007; Nicholson et al., 2011), Yunis-Varon syndrome (Campeau et al., 2013; Nakajima et al., 2013; Wiessner et al., 2013), Bilateral Temporooccipital Polymicrogyria (BTOP) (Ouled Amar Ben Cheikh et al., 2009), and ALS (Chow et al., 2009; Osmanovic et al., 2017; Bertolin et al., 2018).

CMT4J is a highly variable recessive CMT with both axonal and demyelinating defects (Nicholson et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2012). Patient mutations are typically compound heterozygous carrying one null allele and one mutant allele (Chow et al., 2007; Nicholson et al., 2011). Patients with recessive Yunis-Varon syndrome have skeletal defects and neuronal loss that is typically lethal in infancy (Campeau et al., 2013). Patients were either homozygous or compound heterozygous for mutations that are predicted to result in a complete loss of protein function (Campeau et al., 2013). BTOP is a rare recessive disorder with a variable onset from childhood to 20’s resulting in seizures as well as psychiatric and behavioral problems. The homozygous mutation identified in these patients results in a partial loss-of-function (Baulac et al., 2014). Dominant ALS-associated mutations in FIG4 are missense, splicing, and truncating mutations that cause either significant or complete loss-of-function (Chow et al., 2009). Not all known missense mutations are pathogenic, and the association of FIG4 with ALS has begun to be questioned (Verdiani et al., 2013).

The wide range of disease severity in CMT4J and FIG4-associated ALS, combined with the fact that different severities have been seen in patients carrying the same mutation combination in CMT4J (Nicholson et al., 2011) and incomplete penetrance of ALS mutations (Osmanovic et al., 2017), indicates that there are likely genetic or environmental factors that modify the phenotype. There may be a case for CMT4J and FIG4-associated ALS being related diseases since they share mutations (Osmanovic et al., 2017), and lysosomal storage defects are a common feature of all of these disorders

2. Translation & tRNA Biogenesis

Dysregulation of protein synthesis is an emerging commonality in hereditary peripheral neuropathies and motor neuron diseases. The process of decoding mRNA into proteins must be tightly regulated for proper cellular function. Neurons and axons are particularly sensitive to deviations in this regulation, as local axonal translation machinery is limited. Variants in genes encoding for proteins involved in translation are associated with a number of neurodegenerative diseases, ranging from infantile-onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy with Respiratory Distress (SMARD) to CMT and ALS. Both autosomal dominant (AD) and recessive (AR) inheritance patterns have been noted, with different diseases represented by AD or AR inheritance patterns within the same gene. Highlighted here are genes encoding proteins that play a role in protein synthesis and are implicated in a broad spectrum of hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies and MNDs (Fig. 2b) (Table 1).

2.1. IGHMBP2

Autosomal recessive mutations in the Immunoglobulin H μ-binding protein 2 (IGHMBP2) gene result in two clinically distinct diseases: Spinal Muscular Atrophy with Respiratory Distress Type 1 (SMARD1) and Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 2S (CMT2S). IGHMBP2 encodes a ubiquitously expressed dsDNA/dsRNA helicase, found to be localized in the cytoplasm and associated with key translational machinery (Grohmann et al., 2004; De Planell-Saguer et al., 2009, Guenther et al., 2009b). IGHMBP2’s preferred substrate in biochemical assays is dsRNA, highly suggesting that IGHMBP2 plays a role in translation or tRNA processing, as it has also been associated with tRNA fragments (De Planell-Saguer et al., 2009, Guenther et al., 2009b).

Disease-associated Ighmbp2 variants were first identified in a mouse model (nmd2J) (Cox et al., 1998), while a locus containing IGHMBP2 in humans was correlated with patients with early infantile respiratory distress and distal motor impairments (Grohmann et al., 1999). In 2001, Grohmann et al, made the connection between IGHMBP2 mutations and patients of the motor neuron disease, SMARD1, while additionally characterizing the nmd2J mouse model as a SMARD1 model (Grohmann et al., 2001). More recently, Cottenie et al. identified compound heterozygous missense and truncating mutations that were causative of disease symptoms more clinically similar to CMT than SMARD1 (Cottenie et al., 2014; Wagner et al., 2015). Variants in IGHMBP2 have also been linked to cases of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) (Grohmann et al., 1999, 2003; Jackson et al., 2017).

The recessive nature of these diseases, as well as work examining the function and stability of variants reported, suggests that both SMARD1 and CMT2S diseases are caused by loss-of-function alleles (Guenther et al., 2009c, a). Allelic heterogeneity doesn’t solely account for the variability noted in patients, as patients with identical allelic combinations have exhibited phenotypic heterogeneity (Guenther et al., 2009c; Joseph et al., 2009; Hamilton et al., 2015). Some evidence points towards a possible correlation between mutant protein levels and disease severity, as patients with a SMARD1 diagnosis have lower protein levels, while CMT2S patients have reported higher levels (Guenther et al., 2009c). Phenotypic variability may also be driven by genetic modifiers. We have identified a modifier region in the nmd2J mouse model which attenuates the MND, but not a cardiac phenotype (Cox et al., 1998; Maddatu et al., 2005). Interestingly, the modifier region contains a number of tRNAs, strengthening the hypothesis that IGHMBP2 functions in translation or tRNA biogenesis (Maddatu et al., 2004).

2.2. CLP1

CLP1, or cleavage and polyadenylation factor I subunit one, encodes for a kinase involved in tRNA splicing and associated with the tRNA splicing endonuclease (TSEN) complex (Vries et al., 2000; Paushkin et al., 2004). The role of TSEN and CLP1 is to edit out the intron that is present within the anticodon loop of select tRNAs (Weitzer and Martinez, 2007; Hanada et al., 2013). This cleavage event generates 5’ and 3’ tRNA exon halves. CLP1 phosphorylates the 3’ tRNA half, a prerequisite for ligation of the two exonic halves, and the production of a mature tRNA (Weitzer and Martinez, 2007). Editing out the intron of tRNAs is critical for translation, as some tRNA families have only intron-containing genes (van Tol and Beier, 1988).

tRNA processing has been found to be particularly sensitive for cerebellar development, as mutations in human CLP1 are associated with the recessively-inherited Pontocerebellar Hypoplasia Type 10 (PCH10) (Karaca et al., 2014; Schaffer et al., 2014; Wafik et al., 2018). PCH10 is characterized by progressive microcephaly, spasticity, and brain atrophy and delayed myelination (Karaca et al., 2014; Schaffer et al., 2014; Wafik et al., 2018). Additionally, a subset of patients present with axonal sensorimotor neuropathy, similar to CMT2 diseases (Karaca et al., 2014). A homozygous missense variant (p.R140H) identified in these families was found to be in a conserved region of the protein, and impaired in its interaction with members of the TSEN complex (Karaca et al., 2014; Schaffer et al., 2014). Changes in tRNA pre-processing were identified in patient neurons and found to have increased sensitivity to oxidative stress-induced death. These changes in tRNA pre-processing and depletion of mature tRNAs could certainly impair the overall translation ability in motor neurons, increasing stalling due to the depletion of available charged tRNAs (Gorochowski et al., 2015a). To further support the importance of CLP1 to neuron viability, CLP1 kinase-dead mice exhibited neo-natal lethality with impaired innervation of the diaphragm leading to respiratory failure, as well as a loss of motor neurons in the cervical and lumbar spinal cord, decreased level of processed tRNAs, and a sensitivity to oxidative stress (Hanada et al., 2013). Like the Ighmbp2 mouse model, CLP1 kinase-dead mutants were severe on the C57BL/6 background, but were found to be less affected on a CBA/J background, suggesting that some modifier locus exists decreasing motor neuron susceptibility to the Clp1 mutations (Hanada et al., 2013). Such differences in genetic background could explain why patients carrying the same homozygous missense mutation (p.R140H) in two different families presented with heterogeneous phenotypes (Karaca et al., 2014; Schaffer et al., 2014).

2.3. GARS.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (ARSs) are a group of enzymes that catalyze the association of amino acids to the end of their cognate tRNAs. ARSs play a critical role in the interpretation of the genetic code by associating the anticodon sequence of the tRNA to the specific amino acid. Here we discuss the ARS genes that are associated with autosomal dominantly inherited CMTs and distal hereditary motor neuropathies (dHMNs). It should be noted that many of these ARS genes are also associated with multi-systemic autosomal recessive diseases which are not discussed here (Boczonadi et al., 2018).

GARS encodes for both the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial isoforms of glycyl-tRNA synthetases, ensuring that the appropriate tRNAs are charged with glycine. Dominant missense mutations in GARS were first identified in 2003 in families with CMT2D and distal hereditary motor neuropathy type VA (HMN5A) (Antonellis et al., 2003). This has since been supported by a number of familial and individual cases associated with dominant missense variants; however to date no null alleles have been observed (Christodoulou et al., 1995; Ionasescu et al., 1996; Sambuughin et al., 1998; Sivakumar et al., 2005; Del Bo et al., 2006; James et al., 2006; Liao et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2017). The GARS phenotypic spectrum has tentatively been further expanded from inherited peripheral neuropathies (IPNs) to more classical MNDs as a new case study suggests an association with ALS. A patient had developed a late-onset bulbar ALS phenotype and had a familial history of ALS (Corcia et al., 2018). Targeted next-generation sequencing identified a likely pathogenic variant (p.V665L) in a highly conserved region of the anti-codon binding domain of GARS and found no other mutations in known ALS-associated genes (Corcia et al., 2018). Further work determining the pathogenicity of the ALS-associated variant, as well as identifying other cases with GARS variants in bulbar or classical ALS will be informative to strengthen this connection. Overall, these findings indicate that dominant human variants in GARS lead to a spectrum of IPNs such as CMT2D and HMN5A, as well as the potential for later-onset MNDs.

Research determining the pathomechanisms of disease-causing variants has suggested that many are a combination of loss-of-function as well as dominant toxic gain-of-function. Work has suggested that some variants can impair enzymatic activity of GARS, cause localization defects, impair protein translation, and disrupt dimerization through loss-of-function mechanisms (Antonellis et al., 2006; Chihara et al., 2007; Nangle et al., 2007; Griffin et al., 2014; Malissovas et al., 2016). While disruption of the canonical activity and dimerization of GARS has been associated with some disease-associated variants, there is a distinct lack of correlation between canonical loss-of-function and all disease-causing variants. Evidence for a toxic gain-of-function pathomechanism in many of the disease-causing variants has been presented. Work in both mouse and Drosophila models have found that potential neomorphic activity may impair protein translation in motor and sensory neurons, a phenotype which cannot be rescued with overexpression of wildtype protein (Seburn et al., 2006; Motley et al., 2011; He et al., 2015; Niehues et al., 2015). Oprescu et al. highlight a patient with compound heterozygous GARS variants, one which includes a frameshifting putative null allele. The maternal carrier of this null allele was not found to have a CMT2D or HMN5A-like phenotype, further suggesting that haploinsufficiency is not a mechanism of GARS-associated variants. It is plausible that both LOF and GOF variants exist and drive similar phenotypes; however the lack of nonsense and putative null variants in patients with dominant CMT2D and HMN5A, as well as the finding that heterozygous null mice have no discernible phenotype, suggests that a toxic gain-of -function is likely at play.

Such a gain-of-function is likely due to conformational changes of GARS by the disease causing variants, which create novel structures that permit neomorphic binding. Targets for these sites have been identified in a number of studies; observations indicate that mutant GARS can aberrantly associate with Trk receptors, Nrp1, and HDAC6 (He et al., 2015; Sleigh et al., 2017; Mo et al., 2018). Mutant GARS has been found to antagonize the motor neuron VEGF-Nrp1 interaction, which has been implicated in neuronal migration and axonal guidance, however this does not explain why peripheral nerves selectively degenerate (He et al., 2015). Furthermore, mutant GARS aberrantly interact with Trk receptors causing mis-activation of Trk signaling, a process that has proven essential for sensory neuron differentiation and development (Sleigh et al., 2017). This interaction is increased in two of the CMT2D mouse models (GARSC201R/+ and GARSNmf249/+), both of which have sensory involvement. However, what was not tested were variants associated with HMN5A, which may not show spurious mis-activation of Trk. This may be a plausible explanation for the phenotypic heterogeneity of sensory involvement. However, certain variants (p. Ile280Phe and p.Leu129Pro) have been found to segregate with both CMT2D and HMN5A, suggesting that neomorphic Trk receptor binding may not account for all sensory heterogeneity (Sambuughin et al., 1998; James et al., 2006; Liao et al., 2015). Most recently, certain mutant forms of GARS have been shown to aberrantly associate with HDAC6, which impairs α-tubulin acetylation, causing peripheral nerve axonal transport deficits pre-disease onset (Mo et al., 2018). These findings suggest a common, but potentially specific pathomechansim among GARS alleles, by creating stable alternative conformations, which aberrantly interact with various proteins or receptors, causing a cascade of disruption that impacts axonal homeostasis.

Delineating why certain patients present as HMN5A, CMT2D, or ALS, has been difficult as some families present with multiple disease phenotypes (Sivakumar et al., 2005; Del Bo et al., 2006; Corcia et al., 2018). With no apparent allelic segregation, as previously mentioned with the neomorphic Trk receptor binding, it is possible that background genetics increase or decrease susceptibility to certain genetic variants (Sambuughin et al., 1998; Liao et al., 2015). In a CMT2D mouse model, modulating the background strain did alter disease progression and severity (Seburn et al., 2006; He et al., 2015). Likewise, genetic modifiers of disease have been identified in GARS Drosophila models (Ermanoska et al., 2014).

2.4. KARS

KARS, like GARS, is bifunctional in that it encodes for the cytoplasmic and mitochondrial isoforms of the lysyl-tRNA synthetase. However, unlike GARS, only recessive variants have been associated with KARS. The first to be identified was missense variant (p.Leu133His) that significantly impaired enzymatic activity (McLaughlin et al., 2010). This patient presented with an intermediate CMT with axonal and myelination involvement, as well as developmental delay and vestibular Schwannoma. Since this patient diagnosed with CMTRIB, no other KARS-associated CMT patients have been reported. However, there have been multiple reports of patients with neurodegenerative symptoms like leukoencephalopathy, microcephaly, and sensorineural hearing impairment, without peripheral nerve involvement (Santos-Cortez et al., 2013; McMillan et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2017; Ardissone et al., 2018; Scheidecker et al., 2019).

No models exist to study KARS variants, however the international mouse phenotyping consortium (IMPC) found that the knockout of the mouse KARS is homozygous-lethal, as no homozygous mice were observed post-wean, which is expected as lysine would be rendered useless in protein synthesis if left uncharged (Dickinson et al., 2016).

2.5. AARS

Unlike the aforementioned GARS and KARS, AARS only encodes for the cytosolic isoform of alanyl-tRNA synthetase. Dominant and recessive diseases have both been associated with AARS mutations and variants have been identified in all domains. Phenotypic heterogeneity is noted with some families presenting as CMT2N, characterized by distal sensorimotor neuropathy, while other families present with dHMN, lacking sensory involvement (Latour et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2011; McLaughlin et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2012; Bansagi et al., 2015; Motley et al., 2015; Weterman et al., 2018). Research regarding the pathomechanisms of the predominantly missense variants has found impaired amino-acetylation and failed complementation in yeast studies (McLaughlin et al., 2012; Motley et al., 2015; Weterman et al., 2018). However, there may be evidence not only for hypomorphic alleles, but also hypermorphic as Weterman et al., 2018, found that p.Glu337Lys increases tRNA charging velocity.

Animal models of AARS variants confirm neural abnormalities in the zebrafish as well as a mouse model, which has degeneration of the cerebellar Purkinje cells (Lee et al., 2006; Weterman et al., 2018). The AARS mouse model has a point mutation in the editing domain of AARS, which results in an increase in the mischarging of ser-tRNAAla. More recent work has found that ANKRD16 is a genetic modifier of the AARS mutant phenotype, as it prevents the charging of serine adenylates to tRNAAla and is a necessary co-regulator of tRNA synthetase editing; such deletion causes widespread protein aggregation and neuron loss (Vo et al., 2018).

2.6. MARS

MARS only encodes for the cytosolic isoform of methionyl-tRNA synthetase and, like other ARSs, has been implicated in a spectrum of dominant neurodegenerative diseases. To further expand the spectrum, dominant variants in MARS have been associated with a late-onset CMT type 2U. (Gonzalez et al., 2013; Hyun et al., 2014; Hirano et al., 2016; Sagi-Dain et al., 2018). Presentation associated with these dominant variants has been heterogeneous, with some families exhibiting incomplete penetrance, and others presenting far earlier than previously reported (Gonzalez et al., 2013; Sagi-Dain et al., 2018). Additionally, research regarding hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) candidate genes suggests that MARS variants may be causative of HSP, an upper motor neuron disease (Novarino et al., 2014). Future work to better understand the wide spectrum of disease onset and severity, particularly in dominant variant carriers is needed. Addressing if carriers of loss-of-function alleles, such as parents of patients with recessive interstitial lung and liver disease, have a sub-clinical CMT, or perhaps are not yet symptomatic of the later-onset (6–7th decade) CMT2U, will need to be further explored. Additionally, the potential for modifiers that modulate disease susceptibility also needs to be explored; as such mechanisms have begun to be identified in other ARS-associated diseases.

2.7. HARS

HARS, like previously noted ARSs, encodes for the cytosolic histidyl-tRNA synthetase and has been found to be associated with both dominant and recessive disease. As noted in other ARSs, the CMT-associated form of disease is dominantly inherited.

CMT2W, a dominantly inherited disease, has also been linked to the HARS gene (Vester et al., 2013; Safka Brozkova et al., 2015; Abbott et al., 2018; Royer-Bertrand et al., 2019). Presentation of CMT2W is heterogeneous, with some subsets of HARS variants presenting as pure motor axonal neuropathy (Safka Brozkova et al., 2015). One particularly interesting case found a late-onset demyelinating peripheral neuropathy, comorbid with cerebellar atrophy and cognitive deficit, suggesting that not only the PNS may be sensitive to changes in HARS, but also the CNS (Royer-Bertrand et al., 2019). Many of the CMT2W-causing variants have been studied to determine the functional impact to HARS and it has been found that they are able to form stable dimers, but had reduced overall aminoacylation (Vester et al., 2013; Safka Brozkova et al., 2015; Abbott et al., 2018; Royer-Bertrand et al., 2019). While the enzymatic activity of catalyzing the ligation of histidine to its cognate tRNA is reduced, this impact was not shown to reduce overall protein synthesis, as measured by puromycin click-chemistry assay (Royer-Bertrand et al., 2019). While the global translation level is not specifically impacted, it is plausible that a specific subset of proteins critical to axonal maintenance is impaired.

2.8. YARS

YARS gene encodes for the cytosolic tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase. To date a number of cases have associated YARS variants with DI-CMT (Jordanova et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2011; Hyun et al., 2014). Like many of the other CMT-associated ARSs genes, reduction in aminoacylation was observed in mutant proteins (Jordanova et al., 2006). Work in a Drosophila model expressing mutant YARS found progressive deficits in motor performance and axonal degeneration, with the neuron-specific expression inducing the phenotype, suggesting a cell-autonomous effect (Storkebaum et al., 2009). Furthermore, they found these phenotypes are not due to haploinsufficiency of aminoacylation activity but instead are likely due to a dominant-negative or gain-of-function, as seen in the disrupted localization at the axonal termini (Jordanova et al., 2006; Storkebaum et al., 2009). More recent work identified that mutant GARS and YARS-expressing Drosophila models had similar modifiers for the rough eye phenotype, with some modifiers impacting both ARSs, suggesting common pathomechanisms (Ermanoska et al., 2014). Interestingly, the modifiers were specific to the YARS and GARS mutant models, as models of other neurodegenerative disease Gl-Tau and Gl1 (human ortholog of Dynactin 1) were not modified. The enhancement of the rough eye phenotype (mutant-specific enhancers) was only found in the models of YARS/GARS, suggesting a specific interaction of these proteins with the mutant form rather than additive effects unrelated to the disease pathomechanism.

Commonalities between YARS-related toxicity and GARS-related toxicity may address common pathological findings. Such example is the finding that many disease-associated GARS mutations cause stable alternative conformations, YARS variants have also been found to encode proteins with stable and potentially toxic conformations (Blocquel et al., 2017). While disease-causing variants disrupt the conformation of these proteins, as a common mechanism, what these novel stable conformations bind to may be allele specific. Future work assessing other AARs variants for neomorphic binding partners, as a common pathomechanism in GARS and YARS suggest, could identify easily targetable biological pathways as therapeutic avenues.

3. Ribosome-Associated Protein Quality Control

The Ribosome-associated Quality Control (RQC) pathway responds to ribosomes that stall during translation elongation, facilitating resolution by degrading potentially toxic proteins. Ribosomes can stall during translation for a myriad of reasons; a lack of termination codon (nonstop mRNA), increased mRNA secondary structure, or the deficiency of charged tRNAs (no-go mRNA) (Wallen and Antonellis, 2013, Gorochowski et al., 2015b; Simms et al., 2017; Schuller and Green, 2018). Failure to appropriately respond to a stalled ribosomal complex can deplete the translational machinery, a problem that can be particularly apparent in neurons where machinery is extremely limited and translational demand is elevated. Another detrimental effect of improper RQC is the accumulation of misfolded protein products, which could be potentially toxic. Highlighted here are genes encoding for proteins that play essential roles throughout the RQC pathway and are involved in a range of movement and cognitive neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 2c) (Table 1).

3.1. GTPBP2

GTP-binding protein 2 (GTPBP2), and its yeast paralogue of Hbs1, function in ribosomal rescue upstream of RQC. Ribosomes that are stalled at the mRNA 3’ end are sensed by GTPBP2 and its binding partner, pelota (PELO; yeast Dom34). Work in the yeast model system has shown that Hbs1 with Dom34 play a role in non-canonical translation termination and recycling of stalled ribosomes in the 3’ region (Doma and Parker, 2006; Shoemaker et al., 2010; Pisareva et al., 2011).

Variants in GTPBP2 have recently been reported to cause the autosomal recessive Jaberi-Elahi syndrome (Jaberi et al., 2015; Bertoli-Avella et al., 2018; Carter et al., 2019). This neurodegenerative syndrome is early-onset and characterized by the presentation of dystonia, motor and sensory neuropathy, ataxia, cognitive dysfunction, and in some cases brain iron accumulation. It is likely that these variants are hypomorphic loss-of-function alleles, as all reported patients have nonsense or splicing variants leading to a putative null state. While mutations in GTPBP2 do not lead exclusively to CMT diseases, many of the patients exhibit progressive peripheral axonal degeneration and demyelination, suggesting pathomechanistic overlap between CMTs and more global neurodegenerative disorders.

Further insight into the pathomechanisms of GTPBP2 variants has come from mouse model work. A homozygous splice site mutation in mouse Gtpbp2 causes neurodegeneration accompanied with truncal ataxia symptoms, apoptosis of inner granular layer and degeneration of retinal neurons, which are only observable on the C57BL/6J background (Ishimura et al., 2014). Unique to the C57BL/6J strain is a mutation in tRNA-Arg-UCU, an isodecoder that is predominantly expressed in brain tissue, but is not critical in other tissue types. Correction of this tRNA mutation, by utilizing a different genetic background, mitigates the neurodegenerative phenotype. The presence of hypomorphic GTPBP2 as well as an imbalance in tRNA abundance increased ribosomal pausing in the cerebellum. These findings suggest that loss-of-function mutations in GTPBP2 are causative of neurodegenerative disease and can be highly modifiable if ribosomal stalling is decreased. More recent work with this model indicates that the kinase GCN2 is activated in the mutant brain, suggesting that activation of the integrated stress response is a regulatory and neuroprotective mechanism (Ishimura et al., 2016).

3.2. NEMF

NEMF (nuclear export mediator factor) was first identified as serologically defined colon cancer antigen 1 gene (SDCCAG1) (Carbonnelle et al., 1999). Work done in the Drosophila model found that the NEMF orthologue, Caliban, mediates nuclear export of fusion proteins, and is critical for neural differentiation and astrocyte development (Bi et al., 2005). However, since then much of the work regarding understanding the function of NEMF has been performed in the yeast model system. Rqc2 (the yeast NEMF orthologue) works in concert with its cofactor Ltn1 (mammalian Listerin). Rqc2 senses and binds the obstructed 60S subunit and the still-attached charged tRNA. After which, Rqc2 performs two critical roles: the first is to recruit and stabilize the binding of its cofactor Ltn1/Listerin to the stalled 60S subunit; the second is to catalyze the C-terminal elongation of the nascent chain with untemplated alanine and threonine tails (CAT tails) (Bengtson and Joazeiro, 2010; Lyumkis et al., 2014; Shao et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2015). The biological role of CAT-tails still remains largely unknown; however, it is thought that CAT-tails play a role in the activation of stress-response pathways to signal the slowing of translation and/or to increase the likelihood that a lysine substrate within the stalled nascent peptide is available for Ltn1 to ubiquitinate (Choe et al., 2016; Frost et al., 2017).

While not much is known about the role of NEMF in mammalian cells, the neuroprotective nature of GTPBP2 would suggest that aberrations in NEMF may also result in neurodegenerative diseases. One study has found NEMF to be a candidate gene for intellectual disability (Anazi et al., 2017). This study identified two families with independent homozygous truncating variants in NEMF. The patients, two sets of siblings from independent families, presented with global developmental delay, intellectual disability, microcephaly, and hypotonia. While it remains unknown if the hypotonia and global developmental delays are neurogenic in nature, the phenotypic overlap between these cases and the patients with variants in GTPBP2 suggest that deficits in RQC can lead to a spectrum of neurodegenerative diseases, including IPNs and ID.

3.3. LTN1

Listerin (LTN1) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that works in the RQC pathway (Bengtson and Joazeiro, 2010). Ltn1 then ubiquitinates the polypeptide to promote the recruitment of the potentially toxic nascent chain to the proteasome for degradation (Lyumkis et al., 2014; Defenouillère et al., 2016). Failure to ubiquitinate lysine in the nascent chain can cause protein aggregation and signaling of stress-response (Brandman et al., 2012).

While no human diseases are currently associated with mutations in LTN1, a promising mouse model highlights the impact of hypomorphic variants in Ltn1, implicated in peripheral neuropathies and motor neuron diseases (Chu et al., 2009). A splice mutation causes a hypomorphic allele giving rise to a motor neuron disease, while a complete null was found to be embryonic lethal. These findings further support that neurons are vulnerable to disruption in RQC pathways and may suggest that a spectrum of human peripheral and motor neuron disease is associated with pathogenic variants in LTN1.

3.4. VCP

Valosin-containing protein (VCP) is a member of the AAA-ATPase superfamily and plays a role in several cell protein pathways, including protein degradation through autophagic and proteasomal pathways (Hirabayashi et al., 2001; Walther et al., 2001; Rabinovich et al., 2002; Brandman et al., 2012; Defenouillere et al., 2013; van den Boom and Meyer, 2018). In the RQC pathway, VCP is recruited to extract and deliver the ubiquitinated nascent chain to the proteasome for degradation (Defenouillere et al., 2013; Verma et al., 2013). Clearance of the stalled complex is necessary for recycling the ribosome back into the translational pool. Defective ribosome-associated degradation could contribute to the pathophysiology of diseases implicated by variants in VCP.

Variants in VCP are implicated in a spectrum of neurodegenerative and myopathic diseases, predominantly comprised of the autosomal dominantly-inherited inclusion body myopathy with early-onset Paget disease and frontotemporal dementia (IBMPFD), as well as a few cases of sporadic and familial ALS, CMT2, Parkinson’s disease, and HSP. VCP-associated IMBPFD has been found to be highly heterogeneous both intra-familial as well as inter-familial (Haubenberger et al., 2005; van der Zee et al., 2009; Chan et al., 2012; Abrahao et al., 2016). VCP variants alone cannot account for the broad heterogeneity as many of the patients carry p.Arg159His and presentations include FTD alone, IBM with PBD, or any combination of the three (Haubenberger et al., 2005; van der Zee et al., 2009). Further still, this same variant has also been associated with a peripheral neuropathy phenotype, as well as a familial ALS patient, with a strong family history of FTD (Koppers et al., 2012; Segers et al., 2014). Phenotypic overlap is observed in IMBPFD and ALS-FTD, as both can be characterized by TDP-43 positive ubiquitinated inclusions in the muscle and frontal cortex neurons (Cairns et al., 2007; Neumann et al., 2007; Weihl et al., 2008). A review of the genetic spectrum of familial ALS (fALS) found that mutations in VCP may account for 1–2% of all cases, and other work has identified VCP variants associated with a sporadic ALS (sALS) patient (DeJesus-Hernandez et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2011). To further broaden the phenotypic spectrum, cases of CMT2 and peripheral sensorimotor neuropathy, as well as hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) and Parkinson’s Disease have all been associated with variants in VCP (De Bot et al., 2012; Gonzalez et al., 2014; Al-Obeidi et al., 2018).

Pathogenic VCP mutations have been suggested to preferentially disrupt autophagy, leading to cellular degeneration and an accumulation of immature autophagosomes (Ju et al., 2009; Gonzalez et al., 2014). Pathogenic variants were also found to disrupt VCP hexamer formation leading to increased stress-induced toxicity in the Drosophila model (Wang et al., 2016). Mice expressing the p.Arg155His variant exhibited pathology in muscle, brain and bone, recapitulating IBMPFD (Custer et al., 2010). Work from Custer et al., also found that in in vitro studies mutant VCP caused aberrant activation of the NF-kB signaling cascade, which could contribute to the mechanism of pathogenesis in multiple tissues including muscle, bone, and brain. Further studies with the VCP-R155H mouse observed pathology consistent with ALS phenotypes: age-dependent degeneration of the ventral horn motor neurons, TDP-43 positive inclusions, and progressive astrogliosis (Yin et al., 2012). While no patients homozygous for VCP variants have been identified, a homozygous knock-in of the p.Arg155His variant found an earlier-onset, more severe IBMPFD phenotype (Nalbandian et al., 2012). This may suggests that the spectrum of VCP patients may include recessive patients that present at a much earlier time, further expanding the spectrum of overlapping neurodegenerative diseases.

4. Cell Stress Response

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) act as chaperones and monitor for misfolded proteins caused by stressors such as temperature change and UV light. When they detect a misfolded protein, they can either refold the protein into its appropriate tertiary structure or facilitate it towards a proteasome for degradation, promoting cell survival during stressful events (Bakthisaran et al., 2015). If overexpressed, HSPB1, HSPB3, and DNAJB2 have been shown to be neuroprotective in cell cultures modeling Huntington’s, Parkinson’s, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and other neurological diseases associated with deleterious protein folding and aggregation (Carra et al., 2005; Westhoff et al., 2005; Borrell-Pages et al., 2006; Blumen et al., 2012; La Padula et al., 2016; Zarouchlioti et al., 2017). However, when these chaperone proteins are no longer able to properly function proteins aggregate (James and Talbot, 2006; Sanchez et al., 2016). Bound proteins stuck in the aggregates, including HSPs and other homeostatic proteins, are no longer be able to perform their duties. This causes a cascade of other issues to arise, disrupting cell transport, cytoskeletal structure, and ultimately cell death especially for cells that undergo a lot of stress and translation. Neurons are gravely affected when a mutation occurs in fundamental heat shock proteins such as HSPB1, HSPB3, HSPB8, and DNAJB2. The arrest of the homeostatic duties of the heat shock proteins and the number of other processes interrupted by mutations in these genes cause the neurons to degenerate. Though, most mutations in these proteins cause motor neuron death exclusively, it has been seen to sometimes cause sensory neuropathy. Most commonly, mutations in these four genes are associated with an onset of distal motor neuron degeneration. However, in certain cases, both a motor and sensory neuropathy can occur causing an axonal Charcot-Marie-Tooth disorder (Fig. 2d) (Table 1).

4.1. HSPB1

Variants in HSPB1 have been found to have phenotypic heterogeneity and disease overlap, which allele-type alone cannot account for. The S135F variant, found in the α-crystalline domain, was found to cause both dHMN, as well as CMT type 2F (Evgrafov et al., 2004; Chung et al., 2008). Other variants in the same domain also presented as CMT2F or dHMN, but onsets ranged wildly (Kijima et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2005; Houlden et al., 2008). While many of these variants were autosomal dominant dHMN or CMT2F causing, there have been reports of autosomal recessive inheritance of dHMN/CMT2 (Houlden et al., 2008). Phenotypic heterogeneity, especially between patients with the same variant is suggestive that genetic and/or environmental background may impact the severity of the mutation with potential modifiers perhaps mitigating or enhancing the impact of the mutation.

Two transgenic mice have been created based on the human S135F and P182L mutations (D’Ydewalle et al., 2011). These mice had neuron-specific expression of the wildtype or mutated HSPB1 and displayed signs of neuropathy, with differences in onset, severity, and sensory involvement based on allele. The researchers found that these models displayed a decreased α-tubulin acetylation and utilizing pharmacological inhibition of histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6), mitigated the CMT-like phenotype displayed in the models. The inhibition of HDAC6 has also proven beneficial in motor neurons derived from ALS patients with fused in sarcoma (FUS) mutations (Guo et al., 2017) and in HSPB1-induced CMT2 mouse models in pharmacological trials (Benoy et al., 2017).

A single copy of a mutant HSPB1 expressed specifically in the nerves caused CMT-like phenotypes, suggesting a toxic-gain-of-function (D’Ydewalle et al., 2011). Despite being ubiquitously expressed, HSPB1 seems to have a large impact on peripheral motor and sensory nerves. Further studies assessing the CMT/dHMN variable p.S135F mutation in different mouse backgrounds still need to be conducted in order to determine if the severity and sensory nerve loss can be increased or mitigated by possible mouse strain-specific modifiers.

4.2. HSPB8

Very similarly to HSP1, most mutations are autosomal dominant and found in the α-crystallin domain. Three known mutations all occur at a mutational hot spot, lysine 141, in five independent families. Four of these families that carried the same variant K141N displayed distal Hereditary Motor Neuropathy type 2A (dHMN2A) with presentation in the second and third decades of life and rarely a later onset sensory loss (Timmerman et al., 1992b; Irobi et al., 2004). However a Chinese family, also with p.K141N but a different nucleotide change of c.423G>T, displayed a CMT2L phenotype (Tang et al., 2005). Additionally, at this mutational hot spot, a p.K141T mutation had a CMT2L presentation, while p.K141E presented as dHMN2A (Irobi et al., 2004; Nakhro et al., 2013). Work understanding the cellular impact of variants at this site suggests that HSPB8 has greater binding to its interacting partner HSPB1, promoting formation of intracellular aggregates (Irobi et al., 2004).

In 2018, Bouhy et al., found that HSPB8-null mice have comparable locomotor abilities as wildtype mice, while homozygous HSPB8- K141N mice have impaired locomotion and strength (Bouhy et al., 2018). Interestingly, heterozygous-K141N mice do not show impaired locomotor activity or axon loss, unlike the human patients who are carriers. Similar to the in vivo cellular findings from Irobi et al., mutant mice show increased protein aggregations of myofibrils (Bouhy et al., 2018). This suggests that the mutated HSPB8 takes on a dose responsive gain-of-function with two copies of the K141N HSPB8 allele being necessary to show a phenotype.

Interestingly, human patients have also been found to have myopathies without the nerve degeneration aspect. Patients from independent families presented with the same heterozygous two base-pair deletion in the HSPB8 (c.508_509delCA) and late-onset muscle degeneration leading to impaired locomotor abilities (Echaniz-Laguna et al., 2017). This may suggest an even broader disease spectrum related to HSPB8, depending on variant type.

4.3. HSPB3

Mutations in HSPB3 are not as common as the other aforementioned genes. Kolb et al. in 2010 studied candidate HSP genes in patients presenting with peripheral motor neuropathies with or without sensory involvement that did not have mutations in known neuropathy-associated genes, such as IGHMBP2. They found a heterozygous mutation in HSPB3 in 2 siblings presenting with motor axonal degeneration in distal limbs starting in their 20s. This motor neuropathy was restricted to their legs until about 30 years later when their arms started to become affected as well. Interestingly, the mutation found was not in the α-crystallin region, but in the N-terminal domain. The autosomal dominant mutation, R7S, was found in a highly conserved residue of HSPB3 (Kolb et al., 2010).

More recently, the disease spectrum of HSPB3 has expanded, as a dominant CMT2 has been associated with p.Y118H. These patients presented similarly to the previously reported distal HMN, however also had vibration sensory loss and pes cavus.

4.4. DNAJB2

DNAJB2, or HSJ1, is not as closely related to HSPB1, HSPB3, and HSPB8 as they are with each other, but still retains the same roles as the other heat shock proteins of maintaining homeostasis of proteins despite stressors. What makes DNAJB2 unique from HSPB1, HSPB3, and HSPB8 is the J domain which allows DNAJB2 to interact with Hsp70 and assist in resolving protein mis-folding. DNAJB2 is found to protect neurons in vitro from polyQ induced cell death (Borrell-Pages et al., 2006) as well as reduce aggregation of mutant SOD1 in motor neuron like cells in vitro (Blumen et al., 2012)). This participation of DNAJB2 in the resolution of protein aggregates associated with well-known neurodegenerative diseases highlights the importance of this chaperone in mitigating potentially neurotoxic peptides.

The HSPB mutations are predominantly dominant diseases, while the mutations associated with DNAJB2 have been found to be recessive and typically cause splicing defects. Not only are mutations in DNAJB2 associated with CMT and dHMN, but SMA as well. A splicing mutation in DNAJB2 gave rise to a dHMN phenotype, while a missense gave rise to a more CMT2-like, both however presented in their second-third decade (Gess et al., 2014). One family had a large 3.8kb deletion that removed the J domain associated with an SMA diagnosis; one individual also displayed juvenile Parkinsonism with symptoms of not only muscular atrophy, but tremor, and hypokinesia (Sanchez et al., 2016).

The large 3.8kb deletion is not the only allele to show Parkinson’s-like symptoms. One Brazilian family with a splicing mutation shows significant intrafamilial heterogeneity as individuals have presented with cerebellar ataxia, Parkinson’s disease or dHMN. Genetic testing searching for mutations in typical genes associated with parkinsonism, ataxias, and SMA yielded negative results, while whole exome sequencing revealed the 352+1G>A mutation in DNAJB2 (Teive et al., 2016).

5. Conclusions & Perspectives

Unlike Charcot’s anatomoclinical approach, today’s clinicians may turn to genetic screening as the first clinical assessment, particularly with the “1000 dollar” genome nearly in sight. One key to efficiently utilizing a clinicogenetic approach will be determining which variants are pathogenic and which are benign. The current gold standard for determining this includes a multi-faceted approach utilizing population genetics, new powerful modelling and prediction tools as well as functional and segregation data. Furthering the genetic and clinical findings of variants will aid in appropriately interpreting a variant’s potential. Early assessment of the underlying genetic contributions of a given disease is critical as patients, such as those with SMARD, have a very limited window to receive a given therapy prior to irreversible motor neuron death. Therapeutic approaches, like promising gene therapies, are most efficacious when administered at the earliest point. Improved knowledge of the clinical neurogenetics and the spectrum and overlap of inherited axonopathies, MNDs, and other neurodegenerative diseases will aid in the necessary early diagnosis.

Research into the genetics underlying the spectrum of diseases has found that genes contributing to CMTs, HMN, HSPs and MNDs have significantly connected disease modules, forming local connections with each other as they work in related biological pathways (Fig. 1) (Bis-brewer et al., 2019). Among those are biological themes we covered here: axonal trafficking, dysfunction in RNA metabolism and protein homeostasis, and deficits in the cellular stress response (Fig. 2; Table 1). Understanding the molecular pathology of the spectrum and diseases involved in these biological modules will guide research to potential common therapeutic targets and strategies, such as how ALS and SMA have learned from one another (Tosolini and Sleigh, 2017). Cross-over between modules is to be expected, as common pathomechanisms are likely to converge on similar disease phenotypes. Examples of this described here include the changes that variants in GARS and HSPB1 have on HDAC6, causing changes to axonal transport functions. Such findings have observed that for both, HDAC6 inhibitors can attenuate disease severity, indicating a common therapeutic avenue. Furthermore, well-defined family history and advances in genome sequencing technology will improve our knowledge of all genetic contributions to disease, including genetic modifiers that change susceptibility and may potentially shift the spectrum of disease associated with any given variant.

Highlights.

CMT, MNDs and other neurodegenerative diseases share genetic contributions.

Many of these diseases appear to have shared molecular mechanisms.

Clinicogenetics can be useful for the diagnosis of many neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jenn Stauffer for her careful review and insightful editing of the manuscript. We would also like to acknowledge the technical support from BioRender (https://biorender.com/) when producing Figure 2.

Funding Source

This work was supported in part by an NIH R01-NS102414 and the SIMS Family Fund to GAC, and by the University of Maine institutional training grant T32-GM132006 from NIGMS (PIs: L. Liaw and C. Henry) to SEH.

Abbreviations

- AD

Autosomal dominant

- ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- AR

Autosomal recessive

- ARSs

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases

- BTOP

Bilateral temporooccipital polymicrogyria

- CMT

Charcot-Marie-Tooth

- FTD

Frontotemporal dementia

- GOF

Gain of function

- HMN

Hereditary motor neuropathy

- HSP

Hereditary spastic paraplegia

- IBM

Inclusion body myopathy

- IBMPFD

Inclusion body myopathy with Paget disease and frontotemporal dementia

- IMPC

International mouse phenotyping consortium

- IPN

Inherited peripheral neuropathy

- LOF

Loss of function

- MND

Motor Neuron Disease

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- NEIMY

Neonatal intractable myoclonus

- NCV

Nerve conduction velocity

- PBD

Paget’s body disease

- PCH10

Pontocerebellar hypoplasia type 10

- RQC

Ribosome-associated quality control

- SMA

Spinal muscular atrophy

- SMARD

Spinal muscular atrophy with respiratory distress

- SPG

Spastic paraplegia

- TSEN

tRNA splicing endonuclease

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abbott JA, Meyer-Schuman R, Lupo V, Feely S, Mademan I, Oprescu SN, et al. Substrate interaction defects in histidyl-tRNA synthetase linked to dominant axonal peripheral neuropathy. Hum Mutat 2018; 39: 415–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe A, Numakura C, Saito K, Koide H, Oka N, Honma A, et al. Neurofilament light chain polypeptide gene mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: Nonsense mutation probably causes a recessive phenotype. J Hum Genet 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahao A, Abath Neto O, Kok F, Zanoteli E, Santos B, Pinto WBV de R, et al. One family, one gene and three phenotypes: A novel VCP (valosin-containing protein) mutation associated with myopathy with rimmed vacuoles, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Sci 2016; 368: 352–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal PB, Joshi M, Marinakis NS, Schmitz-Abe K, Ciarlini PDSC, Sargent JC, et al. Expanding the phenotype associated with the NEFL mutation neuromuscular disease in a family with overlapping myopathic and neurogenic findings. JAMA Neurol 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Chalabi A, Andersen PM, Nilsson P, Chioza B, Andersson JL, Russ C, et al. Deletions of the heavy neurofilament subunit tail in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Obeidi E, Al-Tahan S, Surampalli A, Goyal N, Wang AK, Hermann A, et al. Genotype-phenotype study in patients with valosin-containing protein mutations associated with multisystem proteinopathy. Clin Genet 2018; 93: 119–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anazi S, Maddirevula S, Salpietro V, Asi YT, Alsahli S, Alhashem A. Expanding the genetic heterogeneity of intellectual disability. Hum Genet 2017; 136: 1419–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonellis A, Ellsworth RE, Sambuughin N, Puls I, Abel A, Jordanova A, et al. Glycyl tRNA Synthetase Mutation in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease Type 2D and Distal Spinal Muscular Atrophy Type V. Am J Hum Genet 2003: 1293–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonellis A, Lee-Lin S-Q, Wasterlain A, Leo P, Quezado M, Goldfarb LG, et al. Functional Analyses of Glycyl-tRNA Synthetase Mutations Suggest a Key Role for tRNA-Charging Enzymes in Peripheral Axons. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 10397–10406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardissone A, Tonduti D, Legati A, Lamantea E, Barone R, Dorboz I, et al. KARS-related diseases: Progressive leukoencephalopathy with brainstem and spinal cord calcifications as new phenotype and a review of literature. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2018; 13: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakthisaran R, Tangirala R, Rao CM. Small heat shock proteins: Role in cellular functions and pathology. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015; 1854: 291–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansagi B, Antoniadi T, Burton-Jones S, Murphy SM, McHugh J, Alexander M, et al. Genotype/phenotype correlations in AARS-related neuropathy in a cohort of patients from the United Kingdom and Ireland. J Neurol 2015; 262: 1899–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer P, Winner B, Schüle R, Bauer C, Häfele V, Hehr U, et al. Identification of a heterozygous genomic deletion in the spatacsin gene in SPG11 patients using high-resolution comparative genomic hybridization. Neurogenetics 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baulac S, Lenk GM, Dufresnois B, Bencheikh BOA, Couarch P, Renard J, et al. Role of the phosphoinositide phosphatase FIG4 gene in familial epilepsy with polymicrogyria. Neurology 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]