Abstract

Purpose

Achilles tendon rupture leads to long term plantar flexor deficits, but some patients recover functional performance better than others. Early indicators of tendon healing could be helpful in establishing patient prognosis and making individualized decisions regarding rehabilitation progression. The purpose of this study was to investigate relationships between early tendon morphology and mechanical properties to long-term heel-rise and jumping function in individuals after Achilles tendon rupture.

Methods

Individuals after Achilles tendon rupture were assessed at 4, 8, 12, 24, and 52 weeks post-injury. Tendon cross sectional area, length, and mechanical properties were measured using ultrasound. Heel-rise and jump tests were performed at 24 and 52 weeks. Correlation and regression analysis were used to identify relationships between tendon structural variables in the first 12 weeks to functional outcomes at 52 weeks, and determine whether the addition of tendon structural characteristics at 24 weeks strengthened relationships between functional performance at 24 and 52 weeks. Functional outcomes of individuals with <3cm of elongation were compared to those with >3cm of elongation using a Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

Twenty-two participants (mean(SD) age=40(11) years, 17 male) were included. Tendon cross-sectional area at 12 weeks was the strongest predictor of heel-rise height (R2=0.280, p=0.014) and work symmetry (R2=0.316, p=0.008) at 52 weeks. Jumping performance at 52 weeks was not significantly related to any of the tendon structural measures in the first 12 weeks. Performance of all functional tasks at 24 weeks was positively related to performance on the same task at 52 weeks (r=0.456–0.708, p<0.05). The addition of tendon cross sectional area improved the model for height LSI (R2=0.519, p=0.001). Tendon elongation >3cm significantly reduced jumping symmetry (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Tendon cross sectional area and excessive elongation related to plantar flexor performance on functional testing after Achilles tendon rupture. Once an individual is able to perform function-based testing, tendon structural measures may inform long-term prognosis. Ultrasound-based measures of tendon structure early in recovery seem to relate to later performance on functional testing. Clinically, assessing tendon structure has the potential to be used as a biomarker of tendon healing early in recovery and better predict patients at risk of negative functional outcome.

Level of evidence

Level 2

Keywords: ultrasound, morphology, viscoelastic properties, ankle

Introduction

Achilles tendon rupture can lead to long term deficits in plantar flexor structure and function [4, 5, 17, 19, 32, 44]. It does seem that there is a spectrum of recovery from this injury with some individuals able to restore running and jumping function while others are not [5, 44]. Even when treatment is standardized [28, 41], there are a variety of factors that contribute to an individual’s ability to recover from characteristics of the injury [21, 43] to patient demographics [1, 12, 27] to patient behaviors and kinesiophobia [26]. Early indicators of tendon healing would be helpful to make informed, individualized decisions regarding the progression of early rehabilitation and better prognose a patient’s potential for recovery.

Several indicators to assist in treatment decision-making and prognostication have been previously described [1, 5, 12, 13, 21, 27, 35, 43]. Older age [1, 27], female sex [1, 12], and higher BMI [27] are associated with poorer outcomes, but are non-modifiable with treatment. Some factors are potentially modifiable with treatment if detected early. Immediately post-injury, gap distance between tendon ends has been found to relate to rerupture risk and long-term outcome [21, 43], measured by the heel-rise test [37] and Achilles tendon Total Rupture Score (ATRS) at one year [24]. At three months post-injury, ATRS has been found to relate to ability to return to play [13]. A heel-rise height deficit of greater than 30% one year post-injury has been associated with alterations in running and jumping biomechanics at five years post-injury [5, 44].

Assessing recovery of tendon morphology and mechanical properties may assist in detecting early healing. Recovery of myotendinous structure has been associated with atrophy of the muscular components of the triceps surae [16, 32] and functional deficits [2, 39, 45]. These relationships have been primarily limited to comparisons within a single time point. Tendon elongation has been associated with deficits in heel-rise height and long-term running and jumping mechanics [5, 44]. Alterations in tendon mechanical properties have also been suggested to affect heel-rise test performance [45], AOFAS score [47], and muscle recruitment during jumping [25]. Modeling studies, however, suggest tendon morphology may have a greater role than mechanical properties in tendon function [14]. From a muscle standpoint, alterations in pennation angle and fascicle length observed experimentally [2, 29] have been suggested to account for decreased heel-rise height in modeling studies [2].

Tendon structure changes over time [18, 22, 23, 34, 46], and there are long-term deficits in myotendinous structure, but the predictive value of structural measures assessed early in recovery to long-term function is not well-described. Relating early tendon structural outcomes to long-term function is limited to two studies reporting associations between tendon structure and functional performance with walking and heel-rise tasks at 6 [46] and 18 months [35] post-injury.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between early tendon morphology and mechanical properties to long-term function on heel-rise and jumping tests in individuals after Achilles tendon rupture. The overarching hypothesis was that tendon morphology and mechanical properties in the first 12 weeks of recovery would relate to functional outcomes at 52 weeks. Additionally, it was anticipated that 24 week functional outcomes would be the strongest indicator of performance on the same tasks at 52 weeks, but it was hypothesized that the addition of tendon structural characteristics at 24 weeks would strengthen the relationship between 24 and 52 week functional outcomes.

Materials and Methods

All tests and measures were performed at our laboratory with the approval of the BLINDED FOR REVIEW Institutional Review Board. Individuals within the first month after an acute Achilles tendon rupture were included. Participants were excluded if they were under 18 years of age; had a history of collagen disorders, peripheral neuropathy, peripheral vascular disorders; or if they did not perform any functional testing at the 52-week time point. Individuals were tested at 4, 8, 12, 24, and 52 weeks after injury. Participants received treatment at the discretion of their healthcare providers, which was not associated with their participation in the study. All participants reported participating in physical therapy, however, their level of participation was not systematically assessed. Results investigating change over the first 24 weeks, physical activity, and the relationship of tendon structure within the first 12 weeks on 24 week outcomes in this group has been previously reported [46]. Participant height and weight, ATRS, physical activity scale (PAS), and Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) was assessed at each time-point. Data were collected regarding duration of immobilization and non-weight bearing.

Tendon Structure Assessment

Tendon length and cross sectional area was measured using B mode ultrasound imaging [33, 38, 45]. Tendon length was assessed using extended field of view settings [33, 38] and tendon cross sectional area was measured at the rupture site. The distance from the calcaneal notch to the rupture site was measured on baseline assessment and these landmarks were used throughout the study.

Tendon material properties were assessed using continuous shear wave elastography [9, 42, 45]. All participants were placed in prone with the knee extended and ankle at 10 degrees dorsiflexion. Due to strain placed on the tendon in this position, measurement in the standardized position was initiated at the 12 week time point. Validity and reliability, including test-retest reliability have been previously reported for all of the ultrasound measures included in this study [8, 9, 38].

Functional Assessment

Participants completed jump [28, 40] and heel-rise testing [37, 40] at 24 and 52 weeks. Reliability for all functional assessments has been previously reported [6, 15, 40]. Jump tests included a unilateral counter movement jump (CMJ), hopping, and drop CMJ as previously described [40]. Jump height (for CMJ and drop CMJ) and plyometric quotient (for hopping) was recorded using a laser mat (MuscleLab, Ergotest, Norway). Performance metrics for CMJ and drop CMJ were averaged over three trials, hopping was averaged over two trials.

The heel-rise test was performed as previously described [37]. Participants stood on a 10 degree incline box and performed unilateral heel-rises to fatigue. A linear encoder (MuscleLab, Ergotest, Norway) attached to the participant’s heel recorded linear displacement, which was used to assess maximum heel-rise height and total work (total linear displacement * body weight).

To account for the effect of height and foot size, all functional testing was assessed using a limb symmetry index (LSI), defined as injured/uninjured value * 100%.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) of all included variables are reported. Pearson correlation was used to investigate the relationships between tendon structural measures in the first 24 weeks and functional testing LSIs at 52 weeks. Significant structural measures were then included in a stepwise regression model predicting LSI. Outliers greater than 3 standard deviations from the mean were excluded from the regression model. Prior work has indicated that there are little to no differences in functional outcome between individuals managed surgically and non-surgically [41]. However, as initial treatment has had mixed findings regarding their effect on structural recovery of the tendon [10, 22], initial treatment strategy was included in the final block of regression models to see if it improved the predictive power of the model.

Prior work has suggests that increased tendon length less than 3 cm may be accommodated for during functional tasks [5, 39]. Due to the lack of variability seen in elongation, as a retrospective analysis the sample was dichotomized into individuals with 3 cm or less elongation and those with greater than 3 cm of elongation at 24 weeks. This time point was selected because it was the average peak elongation at the group level over time. The premise of this analysis was that the musculotendinous unit may be able to accommodate for relatively small amounts of elongation, but if it reaches a critical point then accommodation is not possible. Due to non-normality, Mann-Whitney U Tests were used to identify differences in 52-week functional outcome LSIs between groups.

Data using similar methods across multiple time points were not available to perform an a priori power analysis. Studies using either similar methods within a single time point [45] or different methods across time [35] used sample sizes of 20 individuals. Therefore, we aimed to include similar numbers accounting for attrition. There were a few participants who were unable to complete the functional testing for a variety of reasons (other orthopaedic problems such as knee pain, unrelated medical concerns), in the tables, subject numbers (n) for each analysis are reported.

Results

Twenty-seven individuals were enrolled. Of those, one did not return after the 4-week time point and four did not complete functional testing at the 52-week time point (3 had moved out of the area and 1 was unable due to unrelated health concerns). Therefore, data from 22 individuals are included in this analysis.

Participants were a mean(SD) age of 40(11) years of age (17 male, 5 female; 5 managed non-surgically, 17 managed surgically). Participants had a mean(SD) of 71(15) days in immobilization and 40(24) days non-weight bearing. At the 52 week time point, participants scored a mean(SD) of 91(10) points on the ATRS, 31(7) points on the TSK, and 5(1) on the PAS. This score on the PAS corresponds with, “moderate exercise at least 3 hours a week, e.g. tennis, swimming, jogging, etc.” Ruptured tendons were significantly longer (p<0.001), had greater cross sectional area (p< 0.001), and lower dynamic shear modulus (p=0.001) than the uninjured sides at the 52 weeks (Table 1). Participants performed significantly less heel-rise test height and work (p<0.001) and jumped significantly lower during the CMJ (p=0.008) and drop CMJ (p< 0.001) on their ruptured compared to uninjured side. Performance on hopping was not significantly different between limbs (Table 2).

Table 1.

Tendon Structural Measures Descriptive Statistics

| 4 weeks | 8 weeks | 12 weeks | 24 weeks | 52 weeks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tendon cross sectional area (cm2) | |||||

| Ruptured side | 2.07(0.94) | 2.22(1.25) | 3.15(1.26) | 3.31(1.00) | 2.79(1.32) |

| Uninjured side | 0.62(0.16) | 0.58(0.11) | 0.60(0.14) | 0.61(0.12) | 0.60(0.13) |

| Tendon elongation (cm) | 1.3(1.6) | 1.3(1.5) | 1.6(1.4) | 1.8(1.6) | 1.6(1.8) |

| Dynamic shear modulus (kPa) | |||||

| Ruptured side | --- | --- | 140.7(39.6) | 153.7(33.8) | 178.5(43.9) |

| Uninjured side | --- | --- | 203.1(27.2) | 222.2(36.7) | 230.4(53.1) |

Table 2.

Functional Outcomes Descriptive Statistics

| Limb Symmetry Indexes (%) | 24 weeks | 52 weeks |

|---|---|---|

| Heel-rise test | ||

| Maximum height | 59(31) | 75(21) |

| Total work | 46(28) | 68(26) |

| Counter movement jump height | 69(19) | 87(23) |

| Hopping plyometric quotient | 75(38) | 95(16) |

| Drop counter movement jump height | 71(41) | 78(26) |

Relationship of Tendon Structure and Patient Function

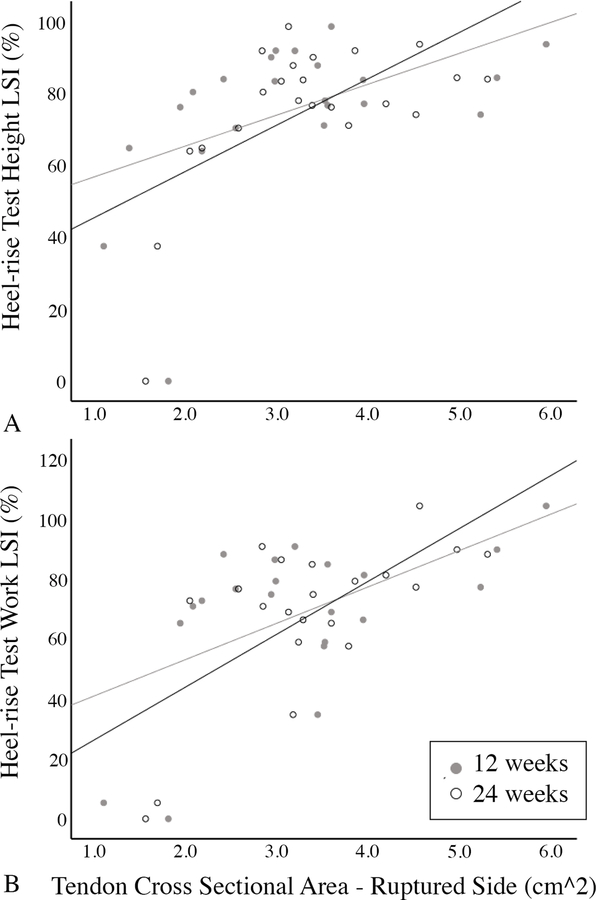

Tendon cross-sectional area at 12 weeks was the single strongest predictor of heel-rise test LSI at 52 weeks (Table 3, Figure 1), and was used in a regression model to predict heel-rise work and height LSIs at 52 weeks. The addition of initial treatment did not significantly improve the model for heel-rise height or heel-rise work, p > 0.05. For heel-rise height LSI, one outlier was identified and removed. This outlier happened to be the oldest individual included in the study. This resulted in a model R2 of 0.280, p=0.014. For heel-rise work LSI, no outliers were identified with a model R2 of 0.316, p=0.008. For both models, cross sectional area was significant (b=.056, β = 0.530, p =0.014; b=0.121, β = 0.562, p= 0.008, respectively). Jumping LSIs at 52 weeks did not significantly relate to any of the tendon structural measures in the first 24 weeks of recovery (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation Analysis

| Functional Outcome at 52 Weeks Limb Symmetry Index (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tendon Structural Characteristic | Time point (weeks) | Heel rise test height | Heel rise test work | CMJ height* | Drop CMJ height | Hopping plyometric quotient |

| Cross sectional area (cm2) | 4 | r=0.344 | r=0.460 | r=0.413 | r=0.379 | r=0.104 |

| n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| n=16 | n=15 | n=15 | n=15 | n=15 | ||

| 8 | r=0.393 | r=0.467 | r=0.395 | r=0.190 | r=0.179 | |

| n.s. | p=0.038 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| n=21 | n=20 | n=19 | n=18 | n=17 | ||

| 12 | r=0.506 | r=0.562 | r=0.211 | r=0.048 | r=0.108 | |

| p=0.016 | p=0.008 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| n=22 | n=21 | n=20 | n=19 | n=18 | ||

| 24 | r=0.602 | r=0.663 | r=0.007 | r=0.219 | r=0.233 | |

| p=0.003 | p=0.001 | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| n=22 | n=21 | n=20 | n=19 | n=18 | ||

| Elongation (cm) | 4 | r=0.014 | r=0.019 | r= −0.036 | r= −0.106 | r= −0.139 |

| n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| n=18 | n=17 | n=17 | n=17 | n=17 | ||

| 8 | r= −0.344 | r= −0.337 | r= −0.104 | r= −0.364 | r= 0.049 | |

| n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| n=22 | n=21 | n=20 | n=19 | n=18 | ||

| 12 | r= −0.128 | r= −0.119 | r= −0.248 | r= −0.339 | r= −0.038 | |

| n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| n=22 | n=21 | n=20 | n=19 | n=18 | ||

| 24 | r= −0.315 | r= −0.279 | r= −0.366 | r= −0.334 | r= −0.334 | |

| n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| n=22 | n=21 | n=20 | n=19 | n=18 | ||

| Dynamic shear modulus (kPa) | 12 | r= −0.005 | r= 0.187 | r= −0.114 | r=0.173 | r=0.285 |

| n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| n=21 | n=20 | n=20 | n=19 | n=18 | ||

| 24 | r= 0.222 | r= 0.219 | r= −0.035 | r= −0.246 | r= 0.421 | |

| n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||

| n=22 | n=21 | n=20 | n=19 | n=18 | ||

Bold values indicate p < 0.05. CMJ counter movement jump.

This analysis was pulled by an outlier with very low CMJ limb symmetry index, and this outlier was removed in the reported data.

Figure 1.

Relationship of tendon cross-sectional area on the ruptured side at 12 and 24 weeks to heel-rise test height (a) and work (b) limb symmetry indexes (LSI) at 1-year

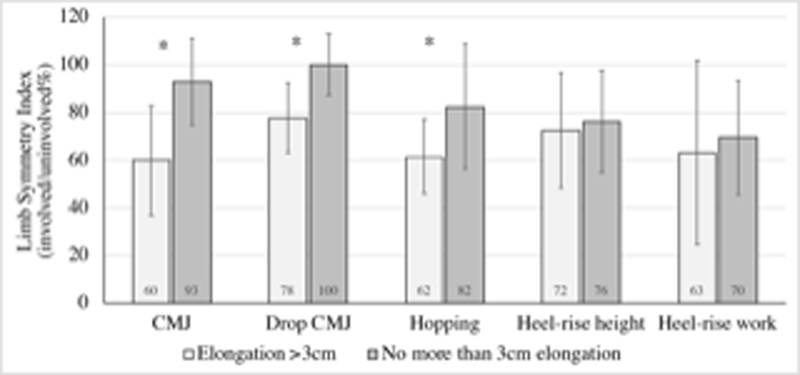

Individuals with more than 3 cm of elongation had significantly lower LSIs for all jumping tasks (Figure 2). There were no differences in heel-rise maximum height or total work LSI (n.s.) between groups based on tendon elongation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Differences in limb symmetry indexes for functional outcomes at 52 weeks between tendon elongation groups at 24 weeks. *p < 0.05

Relationship of 24 and 52 Week Functional Outcomes

Performance of functional tasks at 24 weeks positively related to performance on the same task at 52 weeks (CMJ: r=0.557, p=0.013, n=19; hopping: r=0.708, p=0.001, n=17; drop CMJ: r=0.676, p=0.002, n=18; heel-rise maximum height: r=0.456, p=0.038, n=21; heel-rise work: r=0.671, p=0.002, n=20).

Due to the significant bivariate relationship between heel-rise maximum height performance at 52 weeks with performance at 24 weeks and tendon cross sectional area at 24 weeks, both variables were included in a regression model predicting LSI. Results for the model indicated an R2 of 0.519, p=0.001 with both heel-rise maximum height LSI at 24 weeks (b = 0.289, β = 0.425, p=0.022) and tendon cross sectional area at 24 weeks (b = 0.095, β = 0.448, p=0.017) being significant. The addition of initial treatment did not significantly improve the model (significance F change = 0.611).

Discussion

The most important finding of the present study was that tendon cross sectional area and elongation within the first 6 months of recovery relates to plantar flexor function on the heel-rise test as well as with jumping performance at one-year after Achilles tendon rupture. These findings build on prior work that has investigated relationships between tendon structure and calf functional performance within a single time point [7, 39, 45]. It seems that once an individual is able to perform more function-based testing later in recovery that tendon structural measures may still be informative to long term prognosis.

Recovery of heel-rise height does seem to be of particular importance in this population as it relates to long term outcomes [5, 27, 30, 44]. The results of the present study further suggest that larger tendon cross-sectional area at 12 weeks is associated with improved performance of the heel-rise test at 1 year. Based on our regression model, a 0.06cm2 increase in tendon cross sectional area at 12 weeks was associated with a 1% increase in heel-rise height LSI at 1 year. Similarly, a 0.12cm2 increase in tendon cross sectional area at 12 weeks was associated with a 1% increase in heel-rise work LSI at 1 year. Our data support that once an individual is able to complete a single leg heel-rise, current performance of the heel-rise test serves as the strongest indicator of their future performance of the same task. The challenge, however, is that at 3 months after injury only as many as 50% of patients are able to complete this task [26]. A standardized, seated heel-rise test has been proposed to partially address this issue [3]. It may be that as patients progress through rehabilitation, tendon cross-sectional area followed by seated heel-rise performance and, finally, standing heel-rise performance could be used to indicate long term heel-rise performance.

Contrary to prior work [5, 35, 39, 45], there were no relationships between tendon mechanical properties or elongation and heel-rise performance. Relationships between heel-rise performance and tendon mechanical properties assessed using the same method as the present study have been previously reported [45]. Additionally, a relationship between early Young’s Modulus and later heel-rise performance has been reported [35]. Mechanically, it makes sense that a tendon with larger cross sectional area is capable of transmitting larger forces, which may relate to the ability of patients to do better in functional outcomes. It may be that due to the large changes in tendon cross sectional area in our population, the effect of mechanical properties was much smaller than the effect of the morphology of the tendon, which is consistent with findings from a prior modeling study [14]. Moving forward, it is possible that tendon mechanical properties may be more informative in conditions where there is less magnitude of change in tendon morphology, such as with tendinopathy.

For elongation, it is possible that there was not enough variability within our sample to identify this relationship if it is present. The 24-week time point was the timepoint with the largest difference between maximum and minimum values in the group (7.6 cm), however, all but 4 participants had less than 3 cm of elongation. To put this value into context, a prior study reporting relationships between elongation and heel-rise height had a group median of 3 cm and was comparing heel-rise height and elongation within a single time point [39]. To account for this lack of variability, a cut-off value of 3 cm was used to approximate values relevant to elongation and function performance in past studies [5, 39]. The results of the present study found individuals with greater than 3 cm of elongation performed worse on all of the jumping tasks. While the mean LSI for both heel-rise work and height was lower in the group with greater than 3 cm of elongation, this difference was not statistically significant. It may be that there is a certain amount of tendon elongation that can be compensated through remodeling of the muscular components of the triceps surae [2]. It may be beneficial in future longitudinal studies of larger cohorts to identify whether there is a threshold value for tendon elongation in predicting risk of poor functional outcome.

This study presents data from individuals who had different types of initial treatment and did not receive a standardized treatment protocol. The strength of this approach is that the findings of this study are more generalizeable to the heterogeneous patient population seen by the rehabilitative professional. This approach also presents a limitation, however, as more subtle relationships may be more apparent when controlling for some of this heterogeneity. Multiple factors (such as age or sex) were unable to be controlled for statistically due to the sample size in this exploratory study. That said, the sex distribution of participants in this study is representative of the larger body of individuals with Achilles tendon rupture [11, 20, 31, 36].

It seems like tendon morphological characteristics are a helpful tool at gauging a patient’s healing response after Achilles tendon rupture. Given that placing tensile loads with strengthening exercise has been found to result in increases in tendon cross sectional area [34], it may be that some of these measures could be indicators to make informed decisions regarding the progression of early rehabilitation at the individual level. Clinically, seeing an increase in tendon cross sectional area with a maintenance or slight elongation of tendon length could indicate that the patient is responding well to the level of load provided by the rehabilitative program. Conversely, if there are only minimal increases in tendon cross sectional area or if there are moderate amounts of tendon lengthening, a patient may be at risk of poor long term outcome. From a research standpoint, the findings of this study may be helpful in guiding the assessment of outcomes of pilot treatment protocols before performing studies with long term follow-ups.

The results of this study indicate that increases in cross sectional area with minimal amounts of elongation could indicate a patient is responding favorably to rehabilitation progression. If there is not a substantial increase in cross sectional area or tendon elongation more than 3 cm, there is concern that an individual may have poor functional outcomes at one year.

Conclusion

Tendon cross sectional area at 12 weeks after Achilles tendon rupture was related with plantar flexor function on the heel-rise test at 1 year after Achilles tendon rupture. Excessive tendon elongation at 24 weeks was associated with decreased limb symmetry during jumping tasks at 1 year. Once an individual is able to perform a given functional task, past performance of the task is the best single prognostic indicator of task performance, however, the addition of tendon structural characteristics can improve the prediction of future task performance.

References

- 1.Aujla R, Patel S, Jones A, Bhatia M (2018) Predictors of functional outcome in non-operatively managed Achilles tendon ruptures. Foot Ankle Surg 24:336–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baxter JR, Hullfish TJ, Chao W (2018) Functional deficits may be explained by plantarflexor remodeling following Achilles tendon rupture repair: Preliminary findings. J Biomech 79:238–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brorsson A, Olsson N, Nilsson-Helander K, Karlsson J, Eriksson BI, Silbernagel KG (2015) Recovery of calf muscle endurance 3 months after an Achilles tendon rupture. Scand J Med Sci Sports 26:844–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brorsson A, Silbernagel KG, Olsson N, Helander KN (2017) Calf muscle performance deficits remain 7 years after an Achilles tendon rupture. Am J Sports Med 46:470–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brorsson A, Willy RW, Tranberg R, Grävare Silbernagel K (2017) Heel-rise height deficit 1 year after Achilles tendon rupture relates to changes in ankle biomechanics 6 years after injury. Am J Sports Med 45:3060–3068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne C, Keene DJ, Lamb SE, Willett K (2017) Intrarater reliability and agreement of linear encoder derived heel-rise endurance test outcome measures in healthy adults. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 36:34–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmont MR, Zellers JA, Brorsson A, Olsson N, Nilsson-Helander K, Karlsson J, Silbernagel KG (2017) Functional outcomes of achilles tendon minimally invasive repair using 4- and 6-strand nonabsorbable suture: A cohort comparison study. Orthop J Sport Med 5(8):2325967117723347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corrigan P, Zellers JA, Balascio P, Silbernagel KG, Cortes DH (2019) Quantification of Mechanical Properties in Healthy Achilles Tendon Using Continuous Shear Wave Elastography: A Reliability and Validation Study. Ultrasound Med Biol 45(7):1574–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortes DH, Suydam SM, Silbernagel KG, Buchanan TS, Elliott DM (2015) Continuous shear wave elastography: A new method to measure viscoelastic properties of tendons in vivo. Ultrasound Med Biol 41:1518–1529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freedman B, Gordon J, Bhatt P, Pardes A, Thomas S, Sarver J, Riggin C, Tucker J, Williams A, Zanes R, Hast M, Farber D, Silbernagel K, Soslowsky L (2016) Nonsurgical treatment and early return to activity leads to improved Achilles tendon fatigue mechanics and functional outcomes during early healing in an animal model. J Orthop Res 34:2172–2180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ganestam A, Kallemose T, Troelsen A, Barfod KW (2016) Increasing incidence of acute Achilles tendon rupture and a noticeable decline in surgical treatment from 1994 to 2013. A nationwide registry study of 33,160 patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24:3730–3737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gravare Silbernagel K, Brorsson A, Olsson N, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J, Nilsson-Helander K, Silbernagel KG, Brorsson A, Olsson N, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J, Nilsson-Helander K (2015) Sex differences in outcome after an acute Achilles tendon rupture. Orthop J Sport Med 3(6): 2325967115586768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen M, Christensen M, Budolfsen T, Ostergaard T, Kallemose T, Troelsen A, Barfod K (2016) Achilles tendon total rupture score at 3 months can predict patients’ ability to return to sport 1 year after injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24:1365–1371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hansen W, Shim VB, Obst S, Lloyd DG, Newsham-West R, Barrett RS (2017) Achilles tendon stress is more sensitive to subject-specific geometry than subject-specific material properties: A finite element analysis. J Biomech 56:26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hébert-Losier K, Wessman C, Alricsson M, Svantesson U (2017) Updated reliability and normative values for the standing heel-rise test in healthy adults. Physiotherapy 103:446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heikkinen J, Lantto I, Piilonen J, Flinkkil T, Ohtonen P, Siira P, Laine V, Niinim J, Pajala A, Leppilahti J (2017) Tendon length, calf muscle atrophy, and strength deficit after acute Achilles tendon rupture. J Bone Joint Surg 99:1509–1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heikkinen J, Lantto L, Flinkkila T, Ohtonen P, Pajala A, Siira P, Leppilahti J (2016) Augmented compared with nonaugmented surgical repair after total Achilles rupture: Results of a prospective randomized trial with thirteen or more years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg 98:85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kangas J, Pajala A, Ohtonen P, Leppilahti J (2007) Achilles tendon elongation after rupture repair: A randomized comparison of 2 postoperative regimens. Am J Sports Med 35:59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lantto I, Heikkinen J, Flinkkila T, Ohtonen P, Kangas J, Siira P, Leppilahti J (2015) Early functional treatment versus cast immobilization in tension after Achilles rupture repair: Results of a prospective randomized trial with 10 or more years of follow-up. Am J Sports Med 43:2302–2309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lantto I, Heikkinen J, Flinkkila T, Ohtonen P, Leppilahti J (2015) Epidemiology of Achilles tendon ruptures: Increasing incidence over a 33-year period. Scand J Med Sci Sport 25:e133–e138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrence JE, Nasr P, Fountain DM, Berman L, Robinson AHN (2017) Functional outcomes of conservatively managed acute ruptures of the Achilles tendon. Bone Joint J 99:87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Möller M, Kälebo P, Tidebrant G, Movin T, Karlsson J (2002) The ultrasonographic appearance of the ruptured Achilles tendon during healing: A longitudinal evaluation of surgical and nonsurgical treatment, with comparisons to MRI appearance. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 10:49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mortensen N, Saether J, Steinke M, Staehr H, Mikkelsen S (1992) Separation of tendon ends after Achilles tendon repair: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Orthopedics 15:899–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nilsson-Helander K, Thomeé R, Silbernagel KG, Thomeé P, Faxén E, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J (2007) The Achilles tendon total rupture score (ATRS): Development and validation. Am J Sports Med 35:421–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oda H, Sano K, Kunimasa Y, Komi PV., Ishikawa M (2017) Neuromechanical modulation of the Achilles tendon during bilateral hopping in patients with unilateral Achilles tendon rupture, over 1 year after surgical repair. Sport Med 47:1221–1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsson N, Karlsson J, Eriksson BI, Brorsson A, Lundberg M, Silbernagel KG (2014) Ability to perform a single heel-rise is significantly related to patient-reported outcome after Achilles tendon rupture. Scand J Med Sci Sport 24:152–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsson N, Petzold M, Brorsson A, Karlsson J, Eriksson BI, Grävare Silbernagel K (2014) Predictors of clinical outcome after acute Achilles tendon ruptures. Am J Sports Med 42:1448–1455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olsson N, Silbernagel KG, Eriksson BI, Sansone M, Brorsson A, Nilsson-Helander K, Karlsson J (2013) Stable surgical repair with accelerated rehabilitation versus nonsurgical treatment for acute Achilles tendon ruptures: A randomized controlled study. Am J Sports Med 41:2867–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peng W-C, Chang Y-P, Chao Y-H, Fu S, Rolf C, Shih TT, Su S-C, Wang H-K (2017) Morphomechanical alterations in the medial gastrocnemius muscle in patients with a repaired Achilles tendon: Associations with outcome measures. Clin Biomech 43:50–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Powell HC, Silbernagel KG, Brorsson A, Tranberg R, Willy RW (2018) Individuals post-Achilles tendon rupture exhibit asymmetrical knee and ankle kinetics and loading rates during a drop countermovement jump. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther 48:34–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raikin SM, Garras DN, Krapchev PV (2013) Achilles tendon injuries in a United States population. Foot Ankle Int 34:475–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosso C, Vavken P, Polzer C, Buckland DM, Studler U, Weisskopf L, Lottenbach M, Müller AM, Valderrabano V (2013) Long-term outcomes of muscle volume and Achilles tendon length after Achilles tendon ruptures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 21:1369–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan ED, Rosenberg JG, Scharville MJ, Sobolewski EJ, Thompson BJ, King GE (2013) Test-retest reliability and the minimal detectable change for Achilles tendon length: A panoramic ultrasound assessment. Ultrasound Med Biol 39:2488–2491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schepull T, Aspenberg P (2013) Early controlled tension improves the material properties of healing human achilles tendons after ruptures: A randomized trial. Am J Sports Med 41:2550–2557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schepull T, Kvist J, Aspenberg P (2012) Early E-modulus of healing Achilles tendons correlates with late function: Similar results with or without surgery. Scand J Med Sci Sport 22:18–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheth U, Wasserstein D, Jenkinson R, Moineddin R, Kreder H, Jaglal SB (2017) The epidemiology and trends in management of acute Achilles tendon ruptures in Ontario, Canada. Bone Joint J 99:78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silbernagel KG, Nilsson-Helander K, Thomeé R, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J (2010) A new measurement of heel-rise endurance with the ability to detect functional deficits in patients with Achilles tendon rupture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 18:258–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silbernagel KG, Shelley K, Powell S, Varrecchia S (2016) Extended field of view ultrasound imaging to evaluate Achilles tendon length and thickness: a reliability and validity study. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 6:104–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Silbernagel KG, Steele R, Manal K (2012) Deficits in heel-rise height and Achilles tendon elongation occur in patients recovering from an Achilles tendon rupture. Am J Sports Med 40:1564–1571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silbernagel KGK, Gustavsson A, Thomeé R, Karlsson J, Thomee R, Karlsson J (2006) Evaluation of lower leg function in patients with Achilles tendinopathy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14:1207–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soroceanu A, Sidhwa F, Aarabi S, Kaufman A, Glazebrook M (2012) Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Bone Joint Surg 94:2136–2143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suydam SM, Soulas EM, Elliott DM, Silbernagel KG, Buchanan TS, Cortes DH (2015) Viscoelastic properties of healthy Achilles tendon are independent of isometric plantar flexion strength and cross-sectional area. J Orthop Res 33:926–931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westin O, Nilsson Helander K, Grävare Silbernagel K, Möller M, Kälebo P, Karlsson J (2016) Acute ultrasonography investigation to predict reruptures and outcomes in patients with an Achilles tendon rupture. Orthop J Sport Med 4:1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Willy RW, Brorsson A, Powell HC, Willson JD, Tranberg R, Grävare Silbernagel K (2017) Elevated knee joint kinetics and reduced ankle kinetics are present during jogging and hopping after Achilles tendon ruptures. Am J Sports Med 45:1124–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zellers JA, Cortes DH, Corrigan P, Pontiggia L, Silbernagel KG (2017) Side-to-side difference in Achilles tendon geometry and mechanical properties following Achilles tendon rupture. Muscles, Ligaments, Tendons J 7:541–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zellers JA, Cortes DH, Pohlig RT, Silbernagel KG (2018) Tendon morphology and mechanical properties assessed by ultrasound show change early in recovery and potential prognostic ability for 6 month outcomes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5277-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Zhang L, Wan W, Wang Y, Jiao Z, Zhang L, Luo Y, Tang P (2016) Evaluation of elastic stiffness in healing Achilles tendon after surgical repair of a tendon rupture using in vivo ultrasound shear wave elastography. Med Sci Monit 22:1186–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]