Abstract

Glioblastoma is one of the most lethal forms of adult cancer with a median survival of around 15 months. A potential treatment strategy involves targeting glioblastoma stem‐like cells (GSC), which constitute a cell autonomous reservoir of aberrant cells able to initiate, maintain, and repopulate the tumor mass. Here, we report that the expression of the paracaspase mucosa‐associated lymphoid tissue l (MALT1), a protease previously linked to antigen receptor‐mediated NF‐κB activation and B‐cell lymphoma survival, inversely correlates with patient probability of survival. The knockdown of MALT1 largely impaired the expansion of patient‐derived stem‐like cells in vitro, and this could be recapitulated with pharmacological inhibitors, in vitro and in vivo. Blocking MALT1 protease activity increases the endo‐lysosome abundance, impairs autophagic flux, and culminates in lysosomal‐mediated cell death, concomitantly with mTOR inactivation and dispersion from endo‐lysosomes. These findings place MALT1 as a new druggable target involved in glioblastoma and unveil ways to modulate the homeostasis of endo‐lysosomes.

Keywords: glioma, lysosome, MALT1, mTOR, protease

Subject Categories: Cancer, Autophagy & Cell Death, Membrane & Intracellular Transport

Protease MALT1 impairs lysosome biogenesis and increases mTOR signalling and autophagic flux in glioma stem cells.

Introduction

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) represents the most lethal adult primary brain tumors, with a median survival time of 15 months following diagnosis (Stupp et al, 2009, 2015). The current standard‐of‐care for the treatment of GBM includes a surgical resection of the tumor followed by treatment with alkylating agent temozolomide and radiation. While these standardized strategies have proved beneficial, they remain essentially palliative (Stupp et al, 2009; Chinot et al, 2014; Brown et al, 2016). Within these highly heterogeneous tumors exists a subpopulation of tumor cells named glioblastoma stem‐like cells (GSCs). Although the molecular and functional definition of GSCs is still a matter of debate, there is compelling evidence that these cells can promote resistance to conventional therapies, invasion into normal brain, and angiogenesis (Singh et al, 2004; Bao et al, 2006; Chen et al, 2012; Yan et al, 2013; Lathia et al, 2015). As such, they are suspected to play a role in tumor initiation and progression, as well as recurrence and therapeutic resistance. Owing to their quiescent nature, GSCs resist to both chemotherapy and radiation, which target highly proliferative cancer cells (Bao et al, 2006; Chen et al, 2012). Hence, there is a clear need to identify novel therapeutic targets, designed to eradicate GSCs, in order to improve patient outcome.

GSCs constantly integrate external maintenance cues from their microenvironment and as such represent the most adaptive and resilient proportion of cells within the tumor mass (Lathia et al, 2015). Niches provide exclusive habitat where stem cells propagate continuously in an undifferentiated state through self‐renewal (Lathia et al, 2015). GSCs are dispersed within tumors and methodically enriched in perivascular and hypoxic zones (Calabrese et al, 2007; Jin et al, 2017; Man et al, 2017). GSCs essentially received positive signals from endothelial cells and pericytes, such as ligand/receptor triggers of stemness pathways and adhesion components of the extracellular matrix (Calabrese et al, 2007; Galan‐Moya et al, 2011; Pietras et al, 2014; Harford‐Wright et al, 2017; Jacobs et al, 2017). GSCs are also protected in rather unfavorable conditions where they resist hypoxic stress, acidification, and nutrient deprivation (Shingu et al, 2016; Jin et al, 2017; Man et al, 2017). Recently, it has been suggested that this latter capacity is linked to the function of the RNA‐binding protein Quaking (QKI), in the down‐regulation of endocytosis, receptor trafficking, and endo‐lysosome‐mediated degradation. GSCs therefore down‐regulate lysosomes as one adaptive mechanism to cope with the hostile tumor environment (Shingu et al, 2016).

Lysosomes operate as central hubs for macromolecule trafficking, degradation, and metabolism (Aits & Jaattela, 2013). Cancer cells usually show significant changes in lysosome morphology and composition, with reported enhancement in volume, protease activity, and membrane leakiness (Fennelly & Amaravadi, 2017). These modifications can paradoxically serve tumor progression and drug resistance, while providing an opportunity for cancer therapies. The destabilization of the integrity of these organelles might indeed ignite a less common form of cell death, known as lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP). LMP occurs when lysosomal proteases leak into the cytosol and induce features of necrosis or apoptosis, depending on the degree of permeabilization (Aits & Jaattela, 2013). Recent reports also highlighted that lysosomal homeostasis is essential in cancer stem cell survival (Shingu et al, 2016; Mai et al, 2017; Le Joncour et al, 2019). Additionally, it has been shown that targeting the autophagic machinery is an effective treatment against apoptosis‐resistant GBM (Shchors et al, 2015; Zielke et al, 2018). The autophagic flux inhibitor chloroquine can decrease cell viability and acts as an adjuvant for TMZ treatment in GBM. However, this treatment might cause neural degeneration at the high doses required for GBM treatment (Weyerhäuser et al, 2018). Therefore, it is preferable to find alternative drugs that elicit anti‐tumor responses without harmful effects on healthy brain cells.

A growing body of literature supports the concept of non‐oncogene addiction (NOA) in cancer. Although neither mutated nor involved in the initiation of tumorigenesis, NOA genes are essential for the propagation of the transformed phenotype (Luo et al, 2009). Because NOA gene products are pirated for the benefit of tumor cells’ own survival, their targeting therefore constitutes an Achilles’ heel. Among reported NOA genes and pathways (Staudt, 2010), the paracaspase mucosa‐associated lymphoid tissue l (MALT1) might be of particular interest in GBM (please see Fig 1). This arginine‐specific protease plays a key role in NF‐κB signaling upon antigen receptor engagement in lymphocytes, via the assembly of the CARMA‐BCL10‐MALT1 (CBM) complex. In addition to this scaffold role in NF‐κB activation, MALT1 regulates NF‐κB activation, cell adhesion, mRNA stability, and mTOR signaling through its proteolytic activity (Rebeaud et al, 2008; Staal et al, 2011; Uehata et al, 2013; Hamilton et al, 2014; Jeltsch et al, 2014; Nakaya et al, 2014). MALT1 has been shown to be constitutively active in activated B‐cell‐like diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (ABC DLBCL), and its inhibition is lethal (Ngo et al, 2006; Hailfinger et al, 2009; Nagel et al, 2012). MALT1 was also recently reported to exert pro‐metastatic effects in solid tumors (McAuley et al, 2019). However, the role of MALT1 in solid tumors has not been extensively investigated.

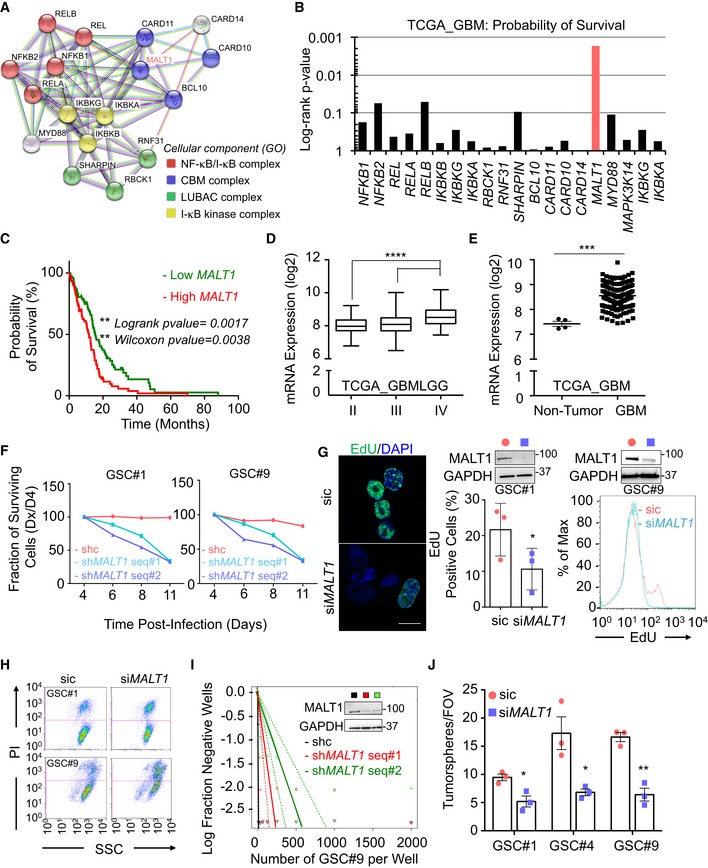

Figure 1. MALT1 expression sustains glioblastoma cell growth.

-

ASTRING diagram representation of the network of proteins involved in NF‐κB pathway.

-

BThe Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA RNAseq dataset) was used on the GlioVis platform (Bowman et al, 2007) to analyze the probability of survival (log‐rank P‐value) of 155 GBM patients, for each gene encoding for the mediators of the NF‐κB pathway.

-

CKaplan–Meier curve of the probability of survival for 155 GBM patients with low or high MALT1 RNA level, using median cutoff, based on the TCGA RNAseq dataset.

-

D, EBox and whisker plot of MALT1 mRNA expression in low‐grade glioma (LGG, grades II and III) or in GBM (grade IV) (TCGA GBMLGG, RNAseq dataset) (D). Horizontal line marks the median, box limits are the upper and lower quartiles, and error bars show the highest and lowest values. Alternatively, MALT1 mRNA expression was plotted in non‐tumor samples versus GBM samples (TCGA RNAseq dataset) (E). Each dot represents one clinical sample.

-

FFraction of surviving cells over time in GSC#1 and GSC#9, transduced with control (shc) or bi‐cistronic GFP plasmids using two different short hairpin RNA (shMALT1 sequences, seq #1 and #2). Data are plotted as the percentage of GFP‐positive cells at the day of the analysis (Dx), normalized to the starting point (day 4 post‐infection, D4).

-

GEdU incorporation (green, 2 h) was visualized by confocal imagery in GSC#1 or by FACS in GSC#9 transfected with sic or siMALT1. In GSC#1, the percentage of EdU‐positive cells was quantified. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. n > 240 cells per replicate. Scale bar: 10 μm. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments.

-

HFACS analysis of propidium iodide (PI) incorporation in GSC #1 and #9 transfected with non‐silencing duplexes (sic) or MALT1 siRNA duplexes (siMALT1) and analyzed 72 h later.

-

ILinear regression plot of in vitro limiting dilution assay (LDA) for control (shc) or shMALT1 seq#1 and seq#2 transduced GSC#9. Data are representative of n = 2. Knockdown efficiency was verified at day 3 by Western blot using anti‐MALT1 antibodies. GAPDH served as a loading control.

-

JTumorspheres per field of view (fov) were manually counted in sic or siMALT1 transfected GSC#1, #4, and #9. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments.

Here, we provide evidence of the role of MALT1 in disrupting GSC lysosomal homeostasis, which is associated with autophagic features. We found that targeting MALT1, notably through the phenothiazine family of drugs, including mepazine (MPZ), is lethal to GBM cells. We further established that MALT1 sequesters QKI and maintains low levels of lysosomes, while its inhibition unleashes QKI and hazardously increases endo‐lysosomes, which subsequently impairs autophagic flux. This leads to cell death concomitant with mTOR inhibition and dispersion from lysosomes. Disrupting lysosomal homeostasis therefore represents an interesting therapeutic strategy against GSCs.

Results

MALT1 expression sustains glioblastoma cell growth

Glioblastoma stem‐like cells (GSCs) are suspected to be able to survive outside the protective vascular niche, in non‐favorable environments, under limited access to growth factors and nutrients (Calabrese et al, 2007; Shingu et al, 2016; Jin et al, 2017). While many signaling pathways can influence this process, the transcription factor NF‐κB has been demonstrated to be instrumental in many cancers as it centralizes the paracrine action of cytokines, in addition to playing a major role in cell proliferation and survival of tumor cells and surrounding cells (Bargou et al, 1996; Davis et al, 2001; Karin & Greten, 2005; Li et al, 2009; McAuley et al, 2019). Because of this dual influence on both tumor cells and their microenvironment, we revisited The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) for known mediators of the NF‐κB pathway (Fig 1A). We found that MALT1 expression was more significantly correlated with survival than other tested genes of the pathway (Fig 1B). This arginine‐specific protease is crucial for antigen receptor‐mediated NF‐κB activation and B‐cell lymphoma survival (Ngo et al, 2006). In addition, when GBM patients were grouped between low and high MALT1 expression levels, there was a significant survival advantage for patients with lower MALT1 expression (Fig 1C). Moreover, levels of MALT1 mRNA are elevated in GBM (Grade IV) when compared with lower grade brain tumors (grades II and III) or non‐tumor samples (Fig 1D and E).

Although this increased MALT1 expression may be due to tumor‐infiltrating immune cells, we first explored whether MALT1 was engaged in patient‐derived GSCs, as these cells recapitulated ex vivo features of the tumor of origin (Lathia et al, 2015). The functional impact of MALT1 knockdown was thus evaluated by their viability and expansion in vitro (Fig 1F–J). Two individual short hairpin RNA sequences targeting MALT1 (shMALT1) cloned in a lentiviral bi‐cistronic GFP‐expressing plasmid were delivered into GSC#1 (mesenchymal) and GSC#9 (classical) cells. We observed a reduced fraction of GFP‐positive cells over time, while cells expressing non‐silencing RNA plasmids (shc) maintained a steady proportion of GFP‐positive cells, indicating that MALT1 silencing was detrimental to GSCs (Fig 1F). Likewise, cells transfected with siMALT1 had a lower percentage of EdU‐positive cells as compared to non‐silenced control cells (Fig 1G) and a higher incorporation of propidium iodide (PI) (Fig 1H). Additionally, GSCs either expressing shMALT1 or transfected with siMALT1 had less stem traits, as evaluated by limited dilution assay and tumorsphere formation (Fig 1I and J). Taken together, these results indicate that MALT1 expression may be important for glioblastoma cell ex vivo expansion.

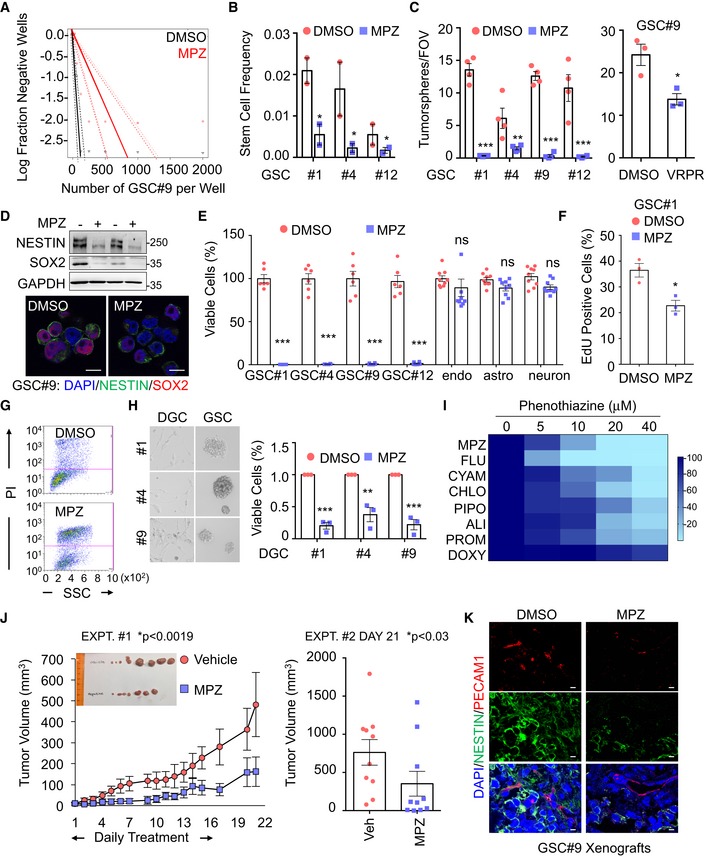

Pharmacological inhibition of MALT1 is lethal to glioblastoma cells

Next, to evaluate the potential of targeting MALT1 pharmacologically, we treated GSC #1 (mesenchymal), #4 (mesenchymal), #9 (classical), and #12 (neural) with the MALT1 allosteric inhibitor mepazine (MPZ) at a dose of 20 μM, as initially described (Nagel et al, 2012). All four GSCs showed a significant reduction in stemness by both limited dilution and tumorsphere assays (Fig 2A–C). Additionally, the competitive inhibitor Z‐VRPR‐FMK induced similar decrease in tumorsphere formation (Fig 2C). This was accompanied by a marked reduction in the abundance of SOX2 and NESTIN stemness markers (Fig 2D). Alongside the in vitro self‐renewal impairment, GSC viability was largely annihilated by MPZ treatment, including reduction in EdU staining and increase in PI incorporation (Fig 2E–G). In contrast, MPZ had no significant effect on viability of brain‐originated human cells (endothelial cells, astrocytes, and neurons), ruling out a non‐selectively toxic effect (Fig 2E). Differentiated sister GSCs (DGCs) also showed reduced viability in response to MPZ, indicating that targeting MALT1 may have a pervasive effect on differentiated GBM tumor cells (Fig 2H).

Figure 2. MALT1 pharmacological inhibition is lethal to glioblastoma cells.

- Linear regression plot of in vitro limiting dilution assay (LDA) for GSC#9 treated with MALT1 inhibitor, mepazine (MPZ, 20 μM, 14 days). DMSO vehicle was used as a control. Data are representative of n = 2.

- Stem cell frequency was calculated from LDA in GSCs #1, #4, and #12 treated with MPZ treatment (20 μM, 14 days). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on two independent experiments.

- Tumorspheres per field of view (fov) were manually counted in GSCs #1, #4, #9, and #12 in response to MPZ (20 μM) and vehicle (DMSO), and in GSC#9 treated with Z‐VRPR‐FMK (75 μM) and vehicle (H2O) for 4 days. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on 4 independent experiments for MPZ and three independent experiments for Z‐VRPR‐FMK.

- The expression of the stemness markers SOX2 and NESTIN was evaluated by Western blot and immunofluorescence (SOX2 in red NESTIN in green) in MPZ (+, 20 μM, 16 h) and vehicle (−, DMSO, 16 h) treated GSC#9. GAPDH served as a loading control. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Cell viability was measured using Cell TiterGlo luminescent assay in GSCs #1, #4, #9, and #12, human brain endothelial cells (endo), human astrocytes (astro), and human neuron‐like cells (neuron) treated for 48 h with DMSO or MPZ (20 μM). Data were normalized to their respective DMSO‐treated controls and are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments in triplicate.

- FACS analysis of EdU staining was performed on GSC#1 treated overnight with MPZ (10 μM). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments.

- FACS analysis of propidium iodide (PI) incorporation in GSC#9 treated for 48 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM).

- Cell viability was measured using Cell TiterGlo luminescent assay in differentiated GSC#1 #4, and #9 (DGCs) treated for 48 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM). Data were normalized to their respective DMSO‐treated controls and are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Morphology of GSCs #1, #4, #9, and DGCs #1, #4, #9 was shown using brightfield images.

- Heatmap of cell viability of GSC#9 using increasing doses (0, 5, 10, 20, 40 μM) of phenothiazines: mepazine (MPZ), fluphenazine (FLU), cyamemazine (CYAM), chlorpromazine (CHLO), pipotiazine (PIPO), alimemazine (ALI), promethazine (PRO), and doxylamine (DOXY). Data were normalized to their respective DMSO‐treated controls.

- Nude mice were implanted with GSC#9 (106 cells) in each flank, and randomized cages were treated with either vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (8 mg/kg) daily i.p., for 14 consecutive days, once tumors were palpable. Tumor volume was measured from the start of treatment until 1 week after treatment was removed. Graph of tumor volume on day 21 post‐treatment is presented. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM n = 10/group.

- Cryosections from GSC‐xenografted tumors were stained for the endothelial marker PECAM1 (red) and tumor marker NESTIN (green). Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bar: 20 μm.

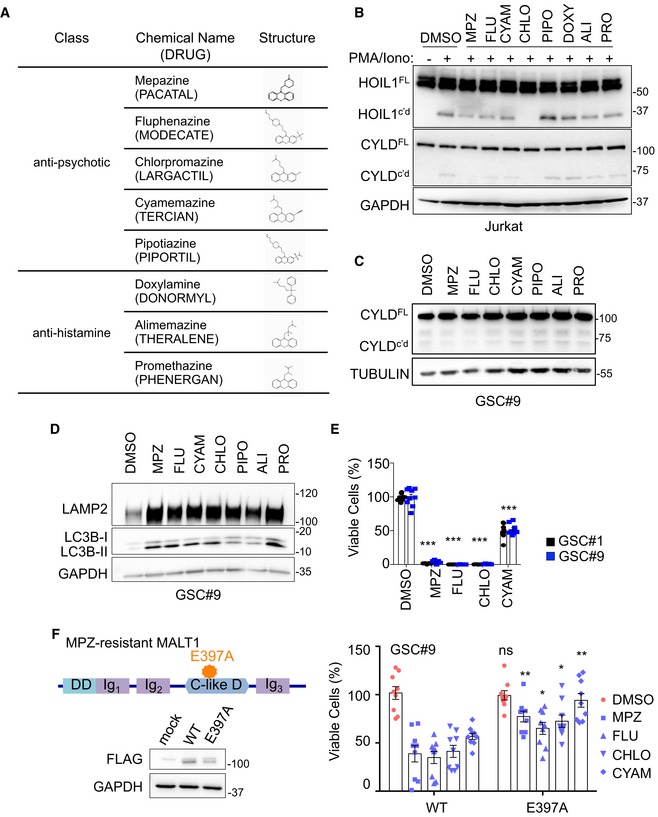

MPZ is a drug, belonging to the phenothiazine family, and was formerly used in the treatment of schizophrenia (Lomas, 1957). Several anti‐psychotic phenothiazines have been shown to potentially reduce glioma growth (Tan et al, 2018). We therefore evaluated whether clinically relevant phenothiazines could affect GSC viability (Fig EV1A–E). The effect on MALT1 inhibition was reflected in cell viability, with chlorpromazine (Oliva et al, 2017) and fluphenazine having robust effects on cell viability (Fig 2I). In addition to its effect on MALT1 protease activity (Fig EV1B and C) (Nagel et al, 2012; Schlauderer et al, 2013), MPZ may also exert off‐target biological effects (Meloni et al, 2018). We took advantage of the well‐characterized MPZ‐resistant E397A MALT1 mutant (Schlauderer et al, 2013) to challenge the toxic action of phenothiazines in GSCs (Fig EV1F). E397A MALT1 expression in GSCs partially restored cell viability in phenothiazine‐treated cells, suggesting that the main target of phenothiazine‐mediated death involves MALT1 inhibition (Fig EV1F). Because MPZ has been shown to efficiently and safely obliterate MALT1 activity in experimental models (Nagel et al, 2012; McGuire et al, 2014; Kip et al, 2018; Di Pilato et al, 2019; Rosenbaum et al, 2019), ectopically implanted GSC#9 mice were challenged with MPZ. Daily MPZ administration reduced tumor volume in established xenografts, as well as NESTIN‐positive staining (Fig 2J and K). This effect was prolonged for the week of measurement following treatment withdrawal (Fig 2J). Together, these data demonstrate that targeting MALT1 pharmacologically is toxic to GBM cells in vitro and in vivo.

Figure EV1. Impact of phenothiazines on MALT1 protease activity and lysosomes.

- Table summarizing eight phenothiazines used in clinics as either anti‐psychotic or anti‐histaminic, along with their generic and brand names (cap letters), and chemical structures.

- Western blot analysis of two MALT1 substrates, HOIL1 and CYLD, either full length (FL) or cleaved (c'd) in Jurkat T cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) or phenothiazines, as follows: 20 μM CYAM (cyamemazine), CHLO (chlorpromazine), PIPO (pipotiazine), DOXY (doxylamine), ALI (alimemazine), and PRO (promethazine), and 10 μM MPZ (mepazine) and FLU (fluphenazine) for 30 min and stimulated for 30 min more with PMA (20 ng/ml) and Ionomycin (Iono, 300 ng/ml). TUBULIN served as a loading control.

- Western blot analysis of CYLD processing in GSC#9 treated with vehicle (DMSO) or phenothiazines (20 μM CYAM, CHLO, PIPO, DOXY, ALI, and PRO, 10 μM MPZ and FLU) for 60 min. GAPDH served as a loading control.

- Western blot analysis of LAMP2 and LC3B in equal amount of total protein lysates from GSC#9 treated for 6 h with vehicle (DMSO) or 20 μM phenothiazines (MPZ, FLU, CYAM, CHLO, ALI, PRO). GAPDH served as a loading control.

- Cell viability of GSC#1 and GSC#9 using 20 μM of MPZ, FLU, CHLO, and CYAM, using Cell TiterGlo assays. Data were normalized to their respective DMSO‐treated controls and are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments in triplicate.

- Schematic drawing of MALT1 structures highlighting the E397A substitution in the mepazine‐resistant version. DD: death domain, C‐like D: caspase‐like domain, Ig: immunoglobulin domain. Western blot analysis of FLAG in equal amount of total protein lysates from HEK‐293T cells transfected with empty vector (mock), MALT‐WT, or MALT1‐E397A. GAPDH serves as a loading control. GSC#9 were transduced with MALT‐WT or MALT1‐E397A and treated with phenothiazines (10 μM of MPZ, FLU, CYAM, CHLO) for 24 h. Cell Viability was analyzed using Cell TiterGlo assay. Data were normalized to their respective DMSO‐treated controls and are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments in triplicate.

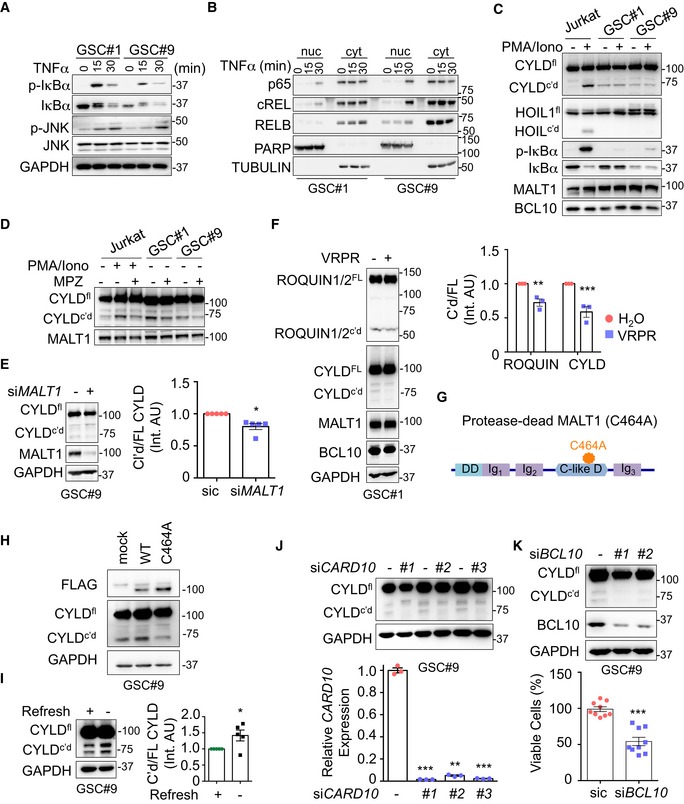

GSCs maintain basal protease activity of MALT1

In addition to its scaffold function in the modulation of the NF‐κB pathway, MALT1 also acts as a protease for a limited number of substrates (Juilland & Thome, 2018; Thys et al, 2018). No hallmarks of NF‐κB activation such as phosphorylation and degradation of IκBα, or p65 and cREL nuclear translocation were observed, unless GSCs were treated with TNFα (Fig 3A and B). Nevertheless, the deubiquitinating enzyme CYLD (Staal et al, 2011) and the RNA‐binding proteins ROQUIN 1 and 2 (Jeltsch et al, 2014), two known MALT1 substrates, were constitutively cleaved in GSCs (Fig 3C–F). This was, however, not the case of the MALT1 target HOIL1 (Douanne et al, 2016), suggesting that only a subset of MALT1 substrates is cleaved in GSCs (Fig 3C). Of note, CYLD proteolysis was not further increased upon stimulation with PMA plus ionomycin, in contrast to Jurkat lymphocytes, most likely due to a failure to co‐opt this signaling route in GSCs (Fig 3C). However, CYLD processing was reduced in cells treated with MPZ or upon siRNA‐mediated MALT1 knockdown (Fig 3D and E). The same was true when MALT1 competitive inhibitor Z‐VRPR‐FMK was used (Fig 3F). Further supporting a role for MALT1 enzyme in GSCs, the expression of a protease‐dead version of MALT1 (C464A) weakened CYLD trimming (Fig 3G and H). Interestingly, we found that refreshing medium also reduced CYLD cleavage, suggesting that MALT1 basal activity may rely on outside‐in signals rather than cell autonomous misactivation (Fig 3I).

Figure 3. MALT1 is active in GSCs.

- Total protein lysates from GSCs #1 and #9 challenged with TNFα (10 ng/ml, for the indicated times) were analyzed by Western blot for p‐IκBα, IκBα, and p‐JNK. Total JNK and GAPDH served as loading controls.

- Western blot analysis of p65, cREL, and RELB in cytosolic (cyt) and nuclear (nuc) cell fractionation from GSC#1 and GSC#9 stimulated with TNFα (10 ng/ml, for the indicated times). TUBULIN and PARP served as controls for each fraction.

- Jurkat T cells, GSC#1, and GSC#9 were stimulated with PMA (20 ng/ml) and ionomycin (Iono, 300 ng/ml) for 30 min. Total protein lysates were analyzed by Western blot for CYLD (full length, FL, and cleaved, c'd), HOIL1 (full length, FL, and cleaved, c'd), p‐IκBα and IκBα. MALT1 and BCL10 served as loading controls.

- Jurkat T cells, GSC#1, and GSC#9 were treated with vehicle (DMSO) and mepazine (MPZ, 20 μM) for 4 h. PMA/ionomycin mixture was also administered to Jurkat cells for the last 30 min. Total protein lysates were analyzed by Western blot for CYLD (full length, FL, and cleaved, c'd). MALT1 served as a loading control.

- Western blot analysis of CYLD (full length, FL, and cleaved, c'd) and MALT1 in total protein lysates from GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing RNA duplexes (sic) or MALT1 targeting duplexes (siMALT1). GAPDH served as a loading control. Densitometric analysis of c'd CYLD/FL CYLD was performed (right). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on five independent experiments.

- (Left) Western blot analysis of CYLD, ROQUIN1/2, MALT1, and BCL10 in total protein lysates from GSC#9 treated for 4 h with vehicle (H2O) or Z‐VRPR‐FMK (75 μM). GAPDH served as a loading control. (Right) Densitometric analysis of c'd/FL was performed for ROQUIN1/2 and CYLD. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments.

- Schematic drawing of MALT1 structures highlighting the C464A substitution in the protease‐dead version. DD: death domain, C‐like D: caspase‐like domain, Ig: immunoglobulin domain.

- Western blot analysis of CYLD and FLAG in total protein lysates from GSC#9 transfected with WT or C464A MALT1‐FLAG. GAPDH served as a loading control.

- Western blot of CYLD (full length, FL, and cleaved, c'd) in total protein lysates from GSC#9 after refreshing the medium (+), as compared to 3‐day‐old culture (−). GAPDH served as a loading control. Densitometric analysis of c'd/FL CYLD was performed. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on five independent experiments.

- Western blot analysis of CYLD (full length, FL, and cleaved, c'd) in total protein lysates from GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing RNA duplexes (sic) or CARD10 targeting duplexes (siCARD10 seq#1, seq#2, and seq#3). GAPDH served as a loading control. qPCR analysis confirmed the knockdown of CARD10 in GSC#9. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments.

- Western blot analysis of CYLD and BCL10 in total protein lysates from GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing RNA duplexes (sic) or BCL10 targeting duplexes (siBCL10, seq#1, and seq#3). GAPDH served as a loading control. Cell viability was measured using Cell TiterGlo luminescent assay in sic and seq#1 siBCL10‐transfected cells. Data were normalized to their respective sic‐treated controls and are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, in triplicate.

The activation of MALT1 habitually occurs within the microenvironment of the CBM complex (Thys et al, 2018). Accordingly, the knocking down of the CBM components BCL10 or CARD10 (i.e., CARMA3) also decreased CYLD processing (Fig 3J and K). In keeping with this, BCL10‐silenced GSC#9 cells showed a reduction in cell viability (Fig 3K), therefore recapitulating the effect of knocking down MALT1. These data reinforce the hypothesis that a fraction of MALT1 is most likely active in growing GSCs, outside its canonical role in antigen receptor signaling and immune cancer cells.

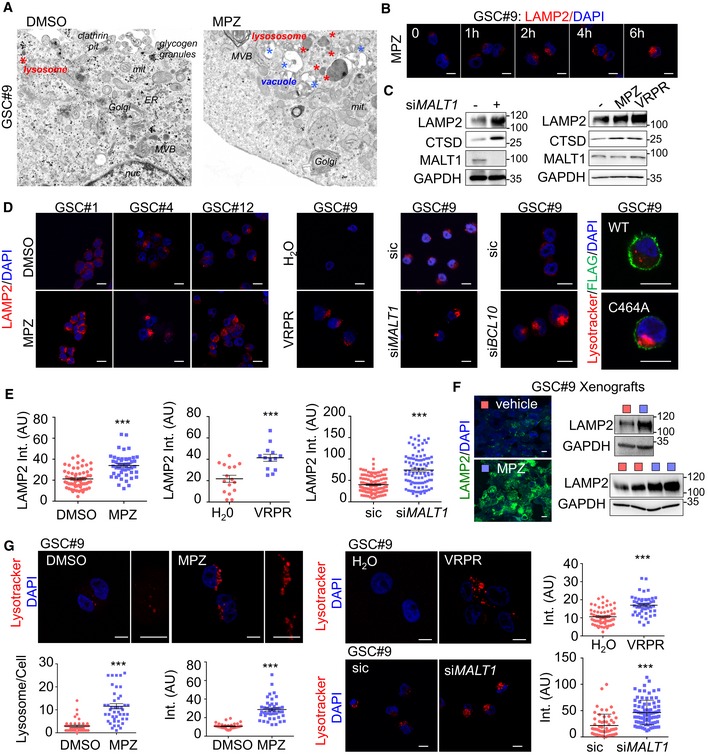

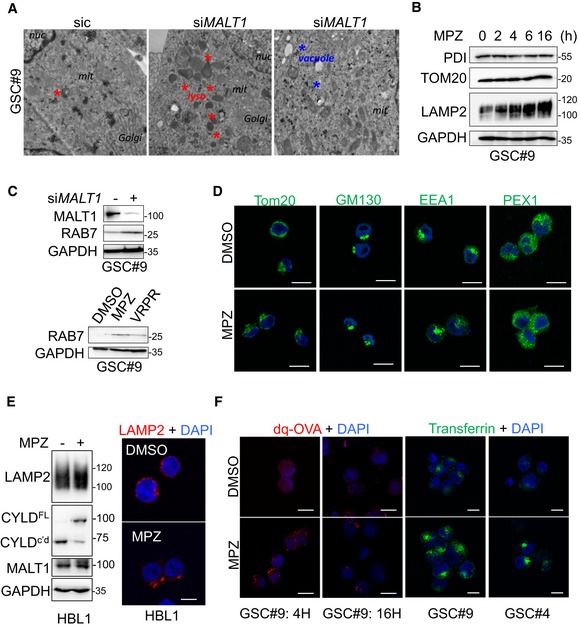

MALT1 inhibition alters endo‐lysosome homeostasis

To evaluate cell death modality triggered by MALT1 inhibition, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was deployed to visualize morphological changes upon MPZ treatment. TEM images showed increased vacuoles and lysosomes compared to control cells (Fig 4A). The augmentation was also visible in siMALT1‐transfected cells (Fig EV2A). In fact, the abundance of the endo‐lysosome protein LAMP2 was amplified upon MALT1 inhibition with MPZ, in a time‐dependent manner (Figs 4B and EV2B). Additionally, treatment with the MALT1 competitive inhibitor Z‐VRPR‐FMK, other phenothiazines, or MALT1 knockdown resulted in similar LAMP2 increase (Figs 4C–E and EV1D), therefore militating against putative drug‐related action or deleterious accumulation in lysosomes. Moreover, the ectopic expression of a protease‐dead MALT1 mutant (C464A) mimicked MPZ effect on lysosome staining, using the lysotracker probe (Fig 4D). In addition, CTSD and Rab7 endo‐lysosomal protein levels were up‐regulated as well upon MALT1 blockade (Figs 4C and EV2C). Conversely, other cellular organelles (early endosomes, mitochondria, Golgi, and peroxisomes) remained unchanged upon MPZ treatment (Fig EV2B and D). Furthermore, ectopic tumors, excised from mice challenged with a MPZ 2‐week regime, showed a marked gain in LAMP2 staining intensity and protein amount, as compared to vehicle‐treated tumors (Fig 4F). Finally, the treatment with MPZ of the ABC DLBCL lymphoma cell line HBL1, which displays constitutive MALT1 activity, also led to an increase in LAMP2 protein amount (Fig EV2E), indicating that MALT1's effect on lysosomal homeostasis might not be limited to GSCs.

Figure 4. MALT1 pharmacological inhibition alters endo‐lysosome homeostasis.

- Transmission electron microscopy of GSC#9 treated with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM) for 16 h. ER: endoplasmic reticulum; MVB: multivesicular bodies; lys: lysosome; mit: mitochondria; nuc: nucleus. Red stars denote lysosomes; blue stars vacuoles.

- Confocal analysis of LAMP2 staining (red) at 0, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h post‐MPZ (20 μM) treatment. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Western blot analysis was performed in total protein lysates from GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing duplexes (sic) or MALT1 targeting siRNA duplexes (siMALT1). Alternatively, Western blot analysis of LAMP2, CTSD, and MALT1 was done in total protein lysates from GSC#9 treated for 16 h with MPZ (20 μM) or Z‐VRPR‐FMK (75 μM). DMSO was used as vehicle. GAPDH served as a loading control.

- Confocal analysis of LAMP2 staining (red) in GSCs #1, #4, #12 treated for 16 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM). Alternatively, GSC#9 were either treated for 16 h with H2O or Z‐VRPR‐FMK (75 μM). Additionally, cells were transfected with non‐silencing duplexes (sic) or MALT1 and BCL10 targeting siRNA duplexes (siMALT1 and siBCL10). Alternatively, lysotracker staining (red) was used to track for lysosomes in either GSC#9 expressing either wild‐type (WT) or C464A FLAG‐MALT1 (green). Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Quantification of LAMP2 staining pixel intensity on GSC#9 treated as described in panel (D). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments. Each dot represents one cell. n > 30.

- Cryosections from GSC#9‐xenografted tumors in vehicle and MPZ‐challenged animals (as described in Fig 2J) and assessed for LAMP2 staining (green). Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bar: 10 μm. Western blot analysis of LAMP2 was performed in tumor lysates. GAPDH served as a loading control.

- Confocal analysis of lysotracker staining (red) in GSC#9 treated for 16 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM). Alternatively, GSC#9 were either treated for 16 h with H2O or Z‐VRPR‐FMK (75 μM) (upper panel) or transfected with sic and siMALT1 (bottom panel). As indicated, number of lysotracker‐positive puncta and lysotracker pixel intensity (arbitrary unit, AU) were quantified per cell. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments. Each dot represents one cell. n > 30. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Figure EV2. Impact of MALT1 inhibition on intracellular organelles.

- Transmission electron microscopy images from GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing duplexes (sic) or siRNA duplexes targeting MALT1 (siMALT1). Multiple images and sections from one experiment were analyzed. Red stars denote lysosomes; blue stars vacuoles.

- Western blot analysis of PDI, TOM20, and LAMP2 in total protein lysates from GSC#9 treated vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM) for the indicated times. GAPDH serves as a loading control.

- Western blot analysis of RAB7 and MALT1 in GSC#9 in total protein lysates from GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing duplexes (sic) or siRNA duplexes targeting MALT1 (siMALT1). Alternatively, GSC#9 received Z‐VRPR‐FMK (VRPR, 75 μM, 16 h) and mepazine (MPZ, 20 μM, 16 h). GAPDH serves as a loading control.

- Confocal analysis of TOM20, GM130, EEA1, and PEX1 immunostaining (green) in GSC#9 treated with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM) for 4 h. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm.

- ABC DLBCL lymphoma cells HBL1 treated with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM) for 4 h. (Left) Western blot analysis of LAMP2 and CYLD (full length, FL, or cleaved, c'd) in total protein lysates. MALT1 and GAPDH serve as loading controls. (Right) Confocal analysis of LAMP2 (red). Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm.

- Confocal analysis of dq‐ovalbumin (dq‐OVA, red) in GSC#9 treated with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM) for 4 or 16 h. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Alternatively, confocal analysis of transferrin uptake (green) in GSC#9 and GSC#4 treated with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM) for 4 h. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm.

The newly formed endo‐lysosomes in GSCs appeared to be at least partially functional, as evidenced by pH‐based Lysotracker staining, DQ‐ovalbumin, and transferrin uptake (Figs 4G and EV2F). Of note, at a later time point (16 h) in MPZ‐treated cells, DQ‐ovalbumin staining was dimmer as compared to early time points (4 h), which might signify lysosomal membrane permeabilization (Fig EV2F). Our data demonstrated that MALT1 knockdown and pharmacological inhibition provoke a meaningful endo‐lysosomal increase.

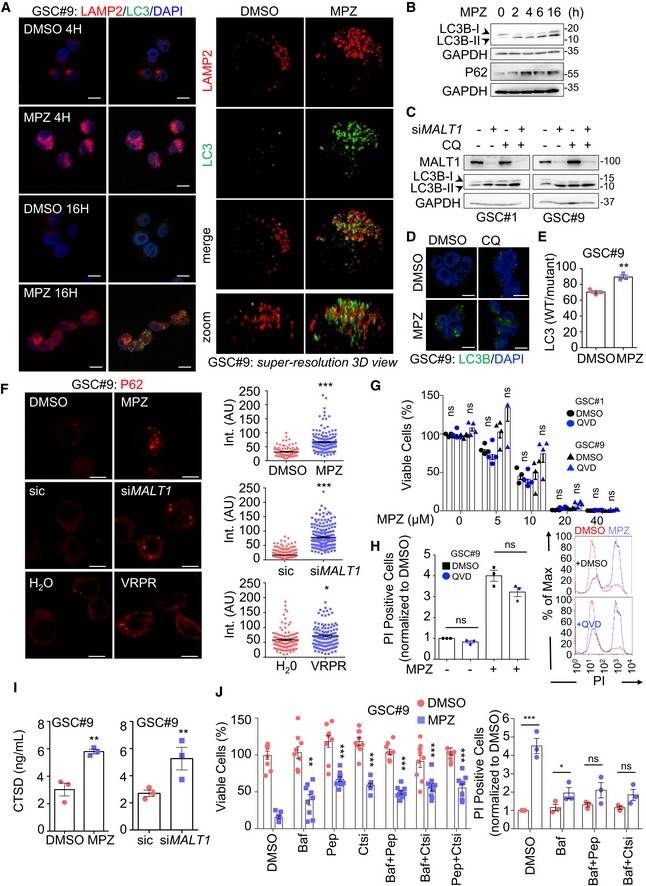

MALT1 inhibition induces autophagic features in GBM cells

Because autophagy is fueled by endo‐lysosomal activity, the impact of MALT1 inhibition on autophagy in GSCs was explored and estimated by LC3B modifications. The turnover of LC3B and the degradation of the autophagy substrate P62 also reflect autophagic flux (Loos et al, 2014). Treatment with MPZ led to a significant increase in LC3B puncta at later time points (16 h), subsequent to lysosomal increase (4 h) (Fig 5A, left panel). Super‐resolution microscopy using structured illumination microscopy (SIM) further revealed that these LC3 structures were covered with LAMP2‐positive staining (Fig 5A, right panel). Upon MPZ treatment, there was also an accumulation of lipidated LC3B (LC3B‐II) and P62 protein amount over time, suggesting impaired autophagic flux (Fig 5B). Likewise, there was an increase in lipidated LC3B protein amount in cells that received phenothiazines or were knocked down for MALT1 (Figs EV1D and 5C). Of note, chloroquine treatment did not further augment LC3 lipidation (Fig 5C and D). The effect of MPZ was concomitant with a reduced LC3B turnover, as evaluated via luciferase assay (Fig 5E), and P62 puncta accumulation in cells treated with MPZ and Z‐VRPR‐FMK, or knocked down for MALT1 (Fig 5F). Taken together, this suggests that MALT1 inhibition impairs autophagic flux in GSCs.

Figure 5. MALT1 inhibition induces autophagic features in GSCs.

- (Left) Confocal analysis of LAMP2 (red) and LC3B (green) in GSC#9 treated for 4 and 16 h with vehicle (DMSO) and MPZ (20 μM). Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm. (Right) Super‐resolution imaging (SIM, Structured Illumination Microscopy) of LAMP2 (red) and LC3B (green) staining in GSC#9 treated for 16 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM).

- Western blot analysis of LC3B and P62 in total protein lysates from GSC#9 at 0, 2, 4, 6, and 16 h post‐MPZ treatment (20 μM). GAPDH served as a loading control.

- Western blot analysis of LC3B in total protein lysates from GSCs #1 and #9 at 72 h post‐transfection with sic or siMALT1 and subsequently treated 4 h with vehicle (DMSO) or chloroquine (CQ, 20 μM). Knockdown was verified by MALT1 blotting and GAPDH served as a loading control.

- Confocal analysis of LC3B (green) in GSC#9 treated for 16 h with vehicle (DMSO) and MPZ (20 μM) with or without chloroquine (CQ, 20 μM). Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm.

- GSC#9 were transfected with LC3B reporters (wild‐type WT or G120A mutant, which cannot be lipidated), treated 24 h later with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM) for 6 more hours. Ratios of WT/mutant luciferase signals are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

- Confocal analysis of P62 staining (red) in GSC#9 treated for 16 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM). Alternatively, GSC#9 was either transfected with sic or siMALT1 (middle) or treated for 16 h with H2O or Z‐VRPR‐FMK (75 μM) (bottom). Quantification of P62 staining pixel intensity on GSC#9 treated for 16 h with vehicle (DMSO or H2O), MPZ (20 μM) or Z‐VRPR‐FMK (75 μM) or sic and siMALT1. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments. Each dot represents one cell. n > 30.

- Cell viability was measuring using Cell TiterGlo in GSCs #1 and #9 pre‐treated for 1 h with vehicle (DMSO) or QVD (20 μM) and treated for 72 h more with the indicated doses of MPZ. Data were normalized to the vehicle‐treated controls and are presented as the mean ± SEM of 4 independent experiments.

- FACS analysis of propidium iodide (PI) incorporation in GSC#9 treated for 48 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (15 μM) in combination with QVD (20 μM). (Left) Percentage of PI‐positive cells, normalized to vehicle‐treated controls are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments. (Right) Histogram plots for representative experiment (DMSO in red and MPZ in blue).

- CTSD ELISA was performed on culture media from GSC#9 treated for 8 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM). Alternatively, cells were transfected with sic or siMALT1 and analyzed 72 h later. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments.

- (Left) Cell viability was measured using Cell TiterGlo luminescent assay in GSC#9 treated for 48 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (10 μM), following a 30‐min pre‐treatment with the following drugs: Bafilomycin A1 (Baf, 100 nM), pepstatin A (Pep, 1 μg/ml), or CTS inhibitor 1 (Ctsi, 1 μM). Data were normalized to the vehicle‐treated controls and are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments in triplicate, stars refer to comparison to vehicle + MPZ group (blue squares). (Right) FACS analysis of propidium iodide (PI) incorporation in GSC#9 treated for 48 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (15 μM) in combination with Baf, Pep, and Ctsi. Percentage of PI‐positive cells normalized to vehicle‐treated controls are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments.

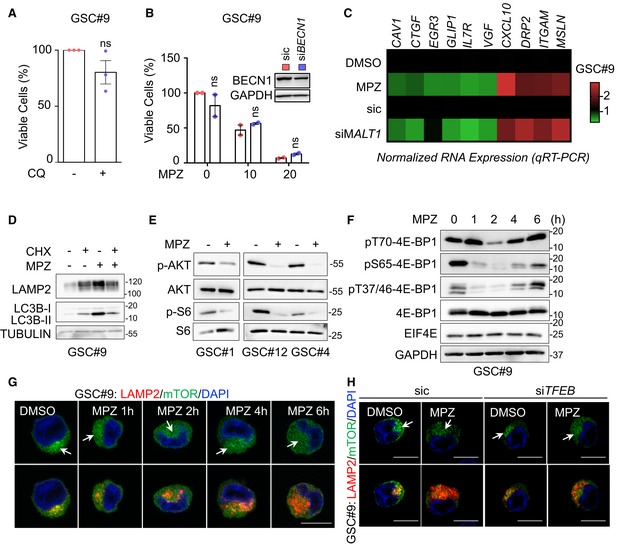

Lysosomes are the cornerstone of MPZ‐induced cell death

To evaluate precisely the mechanism of cell death by MPZ, caspases were simultaneously blocked with Q‐VD‐OPh (QVD) (Fig 5G and H). However, this did not thwart MPZ‐mediated cell death, suggesting another mechanism than apoptosis. Meanwhile, chloroquine treatment did not impact GSC#9 viability (Fig EV3A). Further, cells, in which autophagy was inhibited via knockdown of BECN1 (i.e., BECLIN1), were not protected either, suggesting that autophagy might be secondary to MPZ‐induced cell death (Fig EV3B). Nonetheless, there was increased CTSD release by GSCs treated with MPZ or silenced for MALT1, which could signify either lysosomal membrane permeabilization or increased secretion of lysosomal enzymes (Fig 5I). Accordingly, treatment with lysosomal enzyme inhibitors partially rescued cells from MPZ‐induced cell death (Fig 5J). Thus, lysosomes participate in MPZ‐induced cell death, while MALT1 appears to be required to maintain innocuous level of endo‐lysosomes in GSCs.

Figure EV3. Impact of MALT1 inhibition on cell death and mTOR signaling.

- Cell viability was measured using Cell TiterGlo luminescent assay in GSC#9 treated for 72 h with vehicle (DMSO) or chloroquine (CQ, 20 μM). Data were normalized to the vehicle‐treated controls and are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments in triplicate.

- Cell viability was measured using Cell TiterGlo luminescent assay in GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing duplexes (sic, red) or siRNA duplexes targeting BECLIN1 (siBECN1, blue) and further treated with vehicle (DMSO) and MPZ (10 and 20 μM) for 72 h. Data were normalized to the vehicle‐treated controls and are presented as the mean ± SEM of two independent experiments in triplicate. Knockdown efficiency was checked at the end point by Western blot. GAPDH serves as a loading control.

- GSC#9 were treated with vehicle (DMSO) and mepazine (MPZ, 20 μM) for 16 h. Alternatively, GSC#9 were transfected with non‐silencing duplexes (sic) or siRNA duplexes targeting MALT1 (siMALT1). RNAs were processed for qRT–PCR on 10 gene candidates from RNAseq data (Table EV1). Data are represented as heatmap representation of RNA expression, normalized to two housekeeping genes (HPRT1 and ACTB).

- Western blot analysis of LAMP2 and LC3B in total protein lysates from GSC#9 treated with vehicle (DMSO) and mepazine (MPZ, 20 μM) in the presence of cycloheximide (CHX, 50 μg/ml) for 16 h. TUBULIN served as a loading control.

- Western blot analysis of indicated antibodies in total protein lysates from GSC#1, GSC#12, and GSC#4 that received vehicle (DMSO, −) or mepazine (MPZ, 20 μM, 1 h).

- Western blot analysis of indicated antibodies in total protein lysates from GSC#9 treated vehicle (DMSO) or mepazine (MPZ, 20 μM) for the indicated times. GAPDH serves as a loading control.

- Confocal analysis of LAMP2 (red) and mTOR (green) staining in GSC#9 treated vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM) for the indicated times. Arrows point to LAMP2‐positive area. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm.

- GSC#9 were transfected with sic or siTFEB and treated with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM) for 16 h. Samples were analyzed as described in (G). Arrows point to LAMP2‐positive area. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm.

MALT1 modulates the lysosomal mTOR signaling pathway

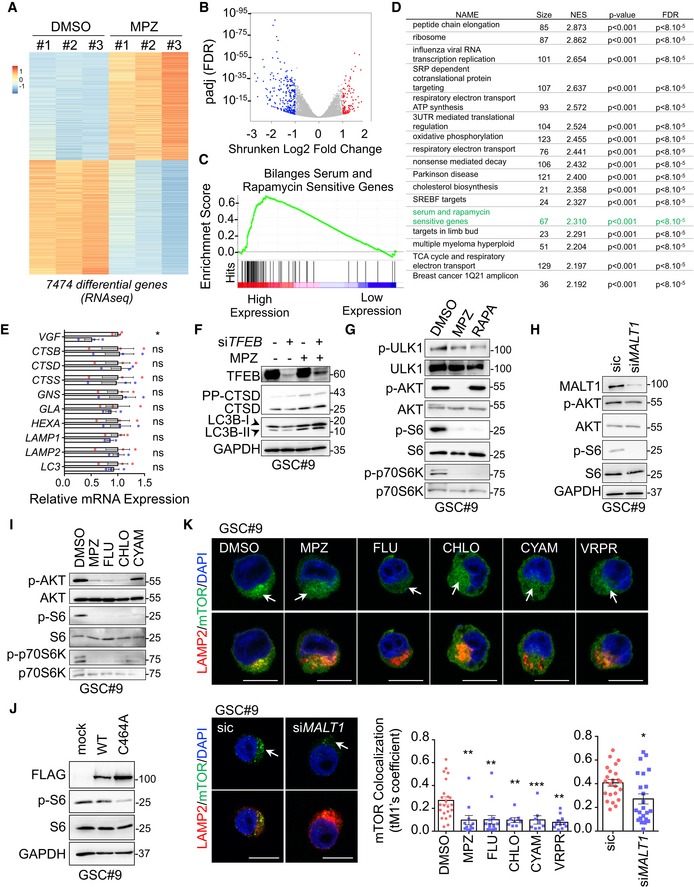

In order to further characterize the mode of action of MALT1 inhibition in GSCs, we performed RNA‐sequencing analysis on GSCs treated with MPZ for 4 h, prior to any functional sign of death. Our results identified 7474 differentially expressed genes, among which 9/10 randomly chosen top candidates were validated in both MPZ‐treated and MALT1‐silenced cells (Figs 6A and EV3C, Table EV1). No obvious endo‐lysosomal protein encoding genes were found, which was further confirmed by qPCR (Fig 6A–E, Table EV1). Of note, VGF, recently shown to promote GSC/DGC survival, was down‐regulated upon MPZ treatment (Wang et al, 2018a) (Figs 6E and EV3C, Table EV1). In line with a non‐transcriptional regulation of lysosome biogenesis, knockdown of the master regulator of lysosomal transcription TFEB (Sardiello et al, 2009) failed to reduce autophagy signature and CTSD protein up‐regulation upon MPZ treatment (Fig 6F). We thus hypothesized that the observed endo‐lysosomal increase was due to modulation in their translation and/or RNA metabolism. When translation was blocked with cycloheximide, MPZ failed to increase endo‐lysosomal protein amounts (Fig EV3D). Likewise, RNAseq analysis unveiled putative changes in translation (peptide chain elongation, ribosome, co‐translational protein targeting, 3′‐UTR mediated translational regulation), RNA biology (influenza viral RNA, nonsense mediated decay), metabolism (respiratory electron transport, ATP synthesis, oxidative phosphorylation, respiratory electron transport), and an mTOR signature (referred as Bilanges serum and rapamycin‐sensitive genes) (Fig 6C and D). Because mTOR sustains GSC expansion and its activation is linked to lysosomal biogenesis (Yu et al, 2010; Galan‐Moya et al, 2011; Settembre et al, 2012), we further explored this possibility. Notably, MALT1 activity has been shown to participate in mTOR activation upon antigen receptor engagement, although the mechanism of action remains poorly understood (Hamilton et al, 2014; Nakaya et al, 2014). In fact, MPZ and phenothiazine pharmacological challenge, as well as MALT1 siRNA blunted mTOR activation in GSCs, as evaluated through the phosphorylation of AKT, p70S6K, and S6 ribosomal protein (Figs 6G–I and EV3E). MPZ treatment also reduced inhibitory phosphorylation of autophagy regulator ULK1 at serine 757 (Fig 6G), which may partially account for increased autophagic features upon MPZ treatment. In addition, the enforced expression of protease‐dead MALT1 (C464A) reduced S6 phosphorylation levels, reiterating the importance of MALT1 catalytic activity in the observed phenotype (Fig 6J). Furthermore, as phosphorylation of 4EBP1 increases protein translation by releasing it from EIF4E (Gingras et al, 1998), and as it can be resistant to mTOR inhibition (Qin et al, 2016), we evaluated 4EBP1 phosphorylation levels over time in response to MPZ (Fig EV3F). Although reduced shortly upon MPZ addition, phosphorylation returned at later time points, which may allow for the observed translational effect despite mTOR inhibition. As mTOR signaling is intimately linked to lysosomes (Korolchuk et al, 2011), we explored the impact of MPZ treatment on mTOR positioning. Confocal microscopy analysis revealed that mTOR staining no longer colocalized with LAMP2‐positive structures upon treatment with MPZ (Figs 6K and EV3G). Interestingly, TFEB silencing did not influence mTOR recruitment at endo‐lysosomes (Fig EV3H). Conversely, mTOR staining appears dispersed from LAMP2 puncta upon Z‐VRPR‐FMK, phenothiazines treatment, or knockdown of MALT1 (Fig 6K). These results suggest that MALT1 affects lysosomal homeostasis post‐transcriptionally, and that the increase in endo‐lysosomes coincides with weakening of the mTOR signaling, which may be due to displacement of mTOR from its lysosomal signaling hub.

Figure 6. MALT1 modulates the lysosomal mTOR signaling pathway.

- Heatmap of differentially expressed genes obtained from RNAseq analysis of GSC#9 treated for 4 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM), from three biological replicates.

- Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in RNAseq analysis of GSC#9, expressed as fold changes between vehicle (DMSO) and MPZ‐treated cells.

- GSEA (gene set enrichment analysis) plot showing enrichment of “Bilanges serum and rapamycin sensitive genes” signature in vehicle (DMSO) versus MPZ‐treated triplicates.

- Table of top differential pathways in DMSO versus MPZ‐treated triplicates. Size of each pathway, normalized enrichment scores (NES), P‐value, and false discovery rate q value (FDR) were indicated.

- qRT–PCR was performed on total RNA from GSC#9 treated for 4 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM). Histograms showed changes in RNA expression of indicated targets. Data were normalized to two housekeeping genes (ACTB, HPRT1) and are presented as the mean ± SEM of technical triplicates.

- Western blot analysis of LC3B, CTSD, and TFEB in total protein lysates from GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing duplexes (sic) or siRNA duplexes targeting TFEB (siTFEB) and treated with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM) for 16 h. GAPDH served as a loading control.

- Western blot analysis of p‐ULK1, p‐AKT, p‐S6, and p‐p70S6K in GSC#9 treated for 1 h with MPZ (20 μM) or rapamycin (RAPA, 50 nM). Total ULK, AKT, S6, and p70S6K served as loading controls. DMSO was used as a vehicle.

- Western blot analysis of MALT1, p‐AKT, and p‐S6 in total protein lysates from GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing duplexes (sic) or MALT1 targeting siRNA duplexes (siMALT1). Total AKT and S6, as well as GAPDH served as loading controls.

- Western blot analysis of p‐AKT, p‐S6, and p‐p70S6K in total protein lysates from GSC#9 treated for 1 h with vehicle (DMSO) or 20 μM of phenothiazine compounds (MPZ, FLU, CHLO, and CYAM). Total AKT, total S6, and total p70S6K served as loading controls.

- Western blot analysis of p‐S6 and FLAG in GSC#9 expressing WT or C464A MALT‐FLAG. Total S6 and GAPDH served as loading controls.

- Confocal analysis of LAMP2 (red) and mTOR (green) staining in GSC#9 treated with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM), Z‐VRPR‐FMK (75 μM), FLU (20 μM), CHLO (20 μM), and CYAM (20 μM). Alternatively, cells were transfected with sic or siMALT1. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Arrows point to LAMP2‐positive area. Scale bars: 10 μm. Quantification of mTOR colocalization score with LAMP2 is shown. The Coloc2 plug‐in from ImageJ was used to measure Mander's tM1 correlation factor in LAMP2‐positive ROI, using Costes threshold regression. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments. Each dot represents one cell. n > 10.

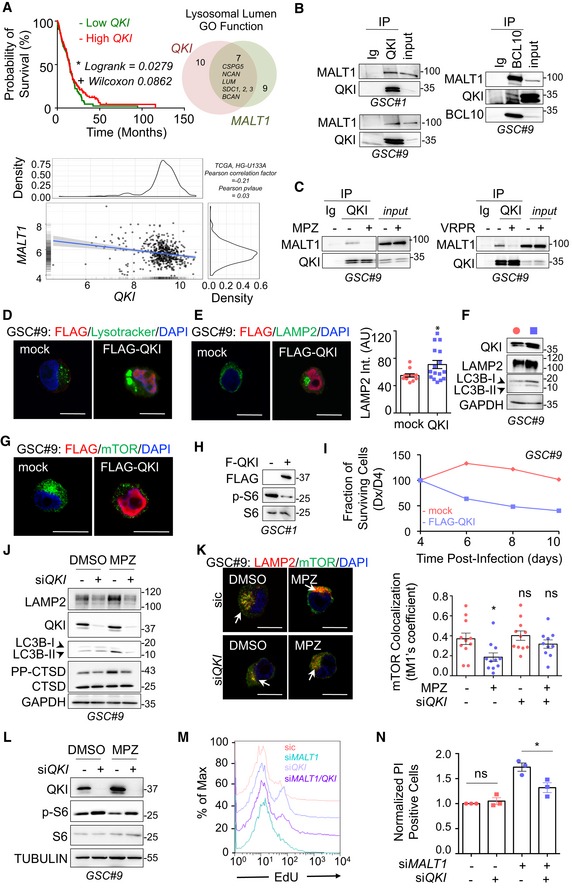

MALT1 is negatively linked to the endo‐lysosomal regulator QKI

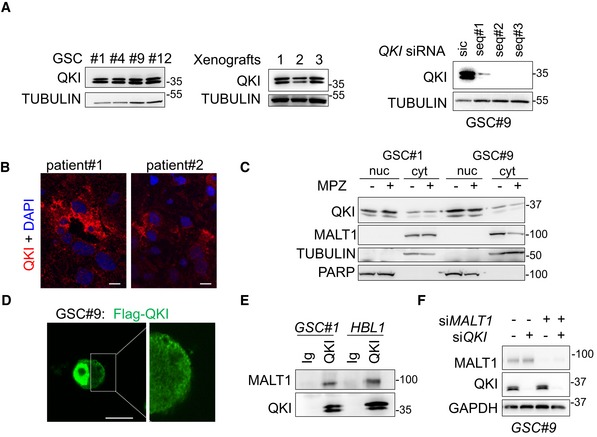

Shinghu et al recently demonstrated that the RNA‐binding protein Quaking (QKI) regulates endo‐lysosomal levels in GBM. They showed that GBM‐initiating cells maintain low levels of endo‐lysosomal trafficking in order to reduce receptor recycling (Shingu et al, 2016). QKI was suggested to regulate RNA homeostasis of endo‐lysosome elements, independently of the TFEB‐driven endo‐lysosome biogenesis. TCGA analysis confirmed the prognosis value of QKI expression in GBM, as patients with higher expression of QKI had a slight survival advantage (Fig 7A). As our data suggest a counterbalancing role of MALT1 in lysosomal biogenesis, we revisited the TCGA and compared the expression of MALT1 with that of QKI in GBM patients. Interestingly, there was a negative correlation between the levels of expression of the two genes (Fig 7A). In addition, QKI and MALT1 were both linked to the expression of 7 common lysosomal lumen genes (Fig 7A). This prompted us to examine QKI pattern in GBM. First, QKI was indeed expressed in a panel of GSCs, as well as in ectopic xenografts (Fig EV4A). Similarly, human GBM samples from two patients showed pervasive QKI staining (Fig EV4B). As expected (Wu et al, 1999), QKI displayed cytosolic and nuclear forms, as evidenced by cellular fractionation and immunofluorescence (Fig EV4C and D). Given these findings, we decided to explore the possible link between MALT1 and QKI in GSCs. Co‐immunoprecipitation experiments were thus deployed using QKI and the MALT1 binding partner BCL10 as baits. This showed that MALT1 was pulled down with QKI in GSC#1 and GSC#9, and vice versa (Fig 7B). Because MALT1 appeared excluded from nuclear fractions, the QKI/MALT1 interaction most likely occurs in the cytosol (Fig EV4C). Binding was, however, reduced in cells exposed to MPZ or Z‐VRPR‐FMK (Fig 7C). This suggests that active MALT1 tethered QKI in GSCs, while blocking MALT1 unleashed a fraction of QKI from the BCL10/MALT1 complex. Of note, QKI and MALT1 readily interacted in HBL1 ABC DLBCL lymphoma cells with constitutive MALT1 activation (Fig EV4E).

Figure 7. MALT1 is negatively linked to the endo‐lysosomal regulator QKI.

- (Left) Kaplan–Meier curve of the probability of survival for 155 GBM patients with low or high QKI RNA level, using median cutoff, based on the TCGA RNAseq dataset. (Right) Differential expression analysis related to either MALT1 or QKI expression highlighted a lysosomal lumen GO function. Venn diagram of overlapping lysosomal enriched protein encoding genes from this comparison showed 7 shared genes, together with 9 and 10 specific genes for MALT1 and QKI expression, respectively. (Bottom) Correlation between MALT1 and QKI expression was analyzed using The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, HG‐U133A dataset) on the GlioVis platform (Bowman et al, 2007). Pearson correlation factor = −0.21, P‐value = 0.03.

- GSCs #1 and #9 protein lysates (input) were processed for immunoprecipitation (IP) using control immunoglobulins (Ig), anti‐QKI, or anti‐BCL10 antibodies. Input and IP fractions were separated on SDS–PAGE and Western blots for MALT1, QKI, and BCL10 antibodies were performed as specified.

- Total protein lysates (input) from GSC#9 treated with vehicle (‐, DMSO) or MPZ (+, 20 μM, 1 h) or with vehicle (‐, H2O) or Z‐VRPR‐FMK (+, 75 μM, 4 h), were processed for control immunoglobulins (Ig) or anti‐QKI antibodies immunoprecipitation (IP). Western blots were performed with indicated antibodies. Western blots were performed with indicated antibodies.

- Confocal analysis of Lysotracker (green) or FLAG (red) in GSC#9 overexpressing either empty vector (mock) or FLAG‐QKI. Scale bars: 10 μm. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue.

- Confocal analysis of LAMP2 (green) or FLAG (red) in GSC#9 transfected with either empty vector (mock) or FLAG‐QKI. Scale bars: 10 μm. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Quantification of LAMP2 staining pixel intensity on GSC#9 transfected with mock and FLAG‐QKI. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments. Each dot represents one cell. n > 15.

- Western blot analysis of QKI, LAMP2, and LC3B in GSC#9 overexpressing either empty vector (mock) or FLAG‐QKI. GAPDH served as a loading control.

- Confocal analysis of mTOR (green) or FLAG (red) in GSC#9 transfected with either empty vector (mock) or Flag‐QKI. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm.

- GSC#1 were transfected with either empty vector (mock) or FLAG‐QKI. Total protein lysates were processed for Western blots against p‐S6 and FLAG. Total S6 served as a loading control.

- Fraction of surviving cells over time in GSCs #1 and #9, transduced with empty vector (mock) or FLAG‐QKI bi‐cistronic GFP plasmids. Data are plotted as the percentage of GFP‐positive cells at the day of the analysis (Dx), normalized to the starting point (Day 4 post‐infection, D4). Data are representative of n = 3.

- GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing RNA duplexes (sic) or QKI targeting siRNA duplexes (siQKI) were treated for 16 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (10 μM). Total protein lysates were processed for Western blots against LAMP2, CTSD, QKI, and LC3B expression, as indicated. GAPDH served as a loading control.

- Confocal analysis of mTOR (green) and LAMP2 (red) in GSC#9 transfected with sic or siQKI and treated for 16 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM). Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm. Quantification of mTOR colocalization score with LAMP2 is shown. The Coloc2 plug‐in from ImageJ was used to measure Mander's tM1 correlation factor in LAMP2‐positive ROI, using Costes threshold regression. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments. Each dot represents one cell. n > 10.

- GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing RNA duplexes (sic) or QKI targeting siRNA duplexes (siQKI) were treated for 1 h with vehicle (DMSO) or MPZ (20 μM). Total protein lysates were processed for Western blots against QKI and p‐S6. TUBULIN and total S6 served as loading controls.

- FACS analysis of EdU staining was performed on GSC#9 cells transfected with non‐silencing RNA duplexes (sic, pink), QKI targeting siRNA duplexes (siQKI, light purple), MALT1 targeting siRNA duplexes (siMALT1, blue), or double‐transfected with siQKI and siMALT1 (purple).

- FACS analysis of propidium iodide (PI) incorporation in GSC#9 transfected with non‐silencing RNA duplexes (sic), QKI targeting siRNA duplexes (siQKI), MALT1 targeting siRNA duplexes (siMALT1) or double‐transfected with siQKI and siMALT1 and analyzed 72 h later. Percentage of PI‐positive cells normalized to vehicle‐treated controls are presented as the mean ± SEM on three independent experiments.

Figure EV4. Characterization of the RNA‐binding protein QKI in glioblastoma cells.

- Western blot analysis of QKI in total protein lysates from GSC #1, #4, #9, #12, and from GSC‐xenografted tumors. Alternatively, GSC#9 were transfected with sic or siQKI using three different duplexes. TUBULIN served as a loading control.

- Confocal analysis of QKI immunostaining (red) in glioblastoma tissue sections from two patients. Nuclei (DAPI) are shown in blue. Scale bars: 10 μm.

- Western blot analysis of QKI in cytosolic (cyt.) and nuclear (nuc.) cell fractionation from GSC#1 and GSC#9, treated with vehicle (−) and mepazine (MPZ, 20 mM, 1 h). TUBULIN and PARP served as loading controls for each fraction. Each panel was replicated at least twice.

- Confocal analysis of FLAG‐QKI (green) localization in transfected GSC#9. Scale bars: 10 μm.

- GSC#1 and HBL1 protein lysates were processed for immunoprecipitation using control immunoglobulins (Ig) and anti‐QKI antibodies. Western blots were performed using anti‐MALT1 and anti‐QKI, as specified.

- GSC#9 were transfected with non‐silencing RNA duplexes (sic), QKI targeting siRNA duplexes (siQKI), MALT1 targeting siRNA duplexes (siMALT1), or double‐transfected with siQKI and siMALT1 and analyzed 72 h later. Knockdown efficiency was checked by Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies.

Source data are available online for this figure.

To next challenge the function of this putative neutralizing interaction of MALT1 and QKI, QKI expression was manipulated to alter QKI/MALT1 stoichiometry in GSCs. Strikingly, transient overexpression of QKI phenocopied the effect of MALT1 inhibition on endo‐lysosomes. Reinforcing pioneer findings of QKI action on endo‐lysosome components in transformed neural progenitors (Shingu et al, 2016), ectopically expressed QKI was sufficient to increase Lysotracker staining, LAMP2 protein amount and lipidated LC3B (Fig 7D–F). Accordingly, the augmented endo‐lysosome staining synchronized with mTOR dispersion from a focalized organization, together with a decrease in the level of S6 phosphorylation (Fig 7G and H). Corroborating the surge of endo‐lysosomes, the fraction of cells overexpressing QKI was drastically reduced over time, while the fraction of cells expressing an empty vector remained stable, suggesting that exacerbated QKI expression hampered cell viability (Fig 7I). Conversely, cells knocked down for QKI did not show the same MPZ‐driven increase in LAMP2, CTSD, and lipidated LC3B (LC3B‐II), suggesting that QKI knockdown can partially rescue cells from endo‐lysosomal increase (Fig 7J and K). Reinforcing this idea, the dissipation of mTOR staining from endo‐lysosomes and the reduction of S6 protein phosphorylation both provoked upon MPZ treatment were no longer observed without QKI (Fig 7K and L). Finally, double knockdown of QKI and MALT1 rescued cells from decreased proliferation and increased cell death triggered by MALT1 depletion (Figs 7M and N, and EV4F). Thus, QKI silencing rescued phenotype upon MALT1 inhibition or knockdown, further indicating that MALT1 is negatively linked to the endo‐lysosomal regulator QKI.

Discussion

Here, we provide evidence that the activity of the paracaspase MALT1 is decisive for growth and survival of GBM cells. Our data indicate that MALT1 inhibition causes indiscipline of endo‐lysosomal and autophagic proteins, which appears to occur in conjunction with a deficit in mTOR signaling. In addition to the known MALT1 inhibitor mepazine (Nagel et al, 2012), we show that several other clinically relevant phenothiazines can potently suppress MALT1 enzymatic activity and have similar effects to MPZ on endo‐lysosomes and cell death in GSCs. Our data with MALT1 and BCL10 silencing, as well as the expression of catalytically dead MALT1, clearly support a role for MALT1 in maintaining the endo‐lysosomal homeostasis in GSCs. Although pharmacological inhibitors largely recapitulated the phenotype obtained with molecular interference, nonselective action of drugs remains of concern when it comes to clinics. Indeed, because some of the less potent MALT1 inhibitors, such as promethazine (Nagel et al, 2012; Schlauderer et al, 2013), also provoke changes LAMP2 and LC3B‐II increase, we cannot exclude that some of the lysosomal effects of phenothiazine derivatives result from potential off‐target accumulation in the lysosome. Likewise, it has been shown that Z‐VRPR‐FMK can efficiently inhibit cathepsin B (Eitelhuber et al, 2015). Nevertheless, since these drugs efficiently cross the blood–brain barrier in humans (Korth et al, 2001) and since they are currently used in the clinic, they represent an exciting opportunity for drug repurposing.

The disruption of endo‐lysosomal homeostasis appears to be the main cause of death upon MALT1 inhibition in GSCs. This is aligned with recent findings that define lysosomes as an Achilles’ heel of GBM cells (Shingu et al, 2016; Le Joncour et al, 2019). As CTSD release is accelerated upon MALT1 blockade, and as inhibitors of lysosomal cathepsins (cathepsin inhibitor 1 and pepstatin A), but not pan‐caspase blockade (QVD), can partially rescue cell viability, we hypothesize that cells may be dying from a form of caspase‐independent lysosomal cell death (LCD) (Aits & Jaattela, 2013). During this form of death, which may also be initiated by cathepsins, lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP) allows cathepsins to act as downstream mediators of cell death upon leakage into the cytosol (Aits & Jaattela, 2013). Additional studies will determine how exactly MALT1 inhibition drives lysosomal death in GSCs. Nevertheless, we found that inhibition of cathepsins provides only partial protection to cells treated with MPZ (Fig 4K). Autophagic features may also play a part in cell death. Induction of autophagy likely occurs due to reduced inhibition of ULK1 (Fig 6G) as a consequence of mTOR dispersion from endo‐lysosomes (Yu et al, 2010; Settembre et al, 2012) (Fig 6K). Whether inducing or blocking autophagy is preferable therapeutic strategy in treating GBM remains up for debate, with some groups reporting beneficial effects of blocking autophagy, and others preferring its activation as a therapeutic strategy (Shchors et al, 2015; Rahim et al, 2017). Here, we show that the observed increased autophagic features are associated with reduced autophagic flux. Impairment in autophagic flux reduces a cell's ability for bulk degradation (Loos et al, 2014). Others have shown that lysosomal dysfunction, such as LMP, can impede upon autophagic flux and eventually lead to cell death (Elrick & Lieberman, 2013; Wang et al, 2018b). Because of this, we infer that reduced autophagic flux is a downstream consequence of LMP and ultimately contributes to LCD in our cells.

MALT1 has previously been linked to mTOR activity (Hamilton et al, 2014; Nakaya et al, 2014). For instance, MALT1 was reported to be necessary for glutamine uptake and mTOR activation after T‐cell receptor engagement (Nakaya et al, 2014). Subsequently, the inhibition of MALT1 with Z‐VRPR‐FMK causes a reduction in the phosphorylation of S6 and p70S6K (Hamilton et al, 2014). Our data now extend these findings to GSCs, although the exact mechanism by which mTORC1 inhibition occurs remains to be explored in both cellular backgrounds. Immunofluorescence analysis of mTOR positioning after MPZ treatment suggests that inhibition of mTOR is linked to its dispersion from the endo‐lysosomes, concurrent with lysosomal increase. In addition to a reduction in mTORC1 signaling, AKT phosphorylation was also impaired upon MALT1 inhibition in GSCs. It is thus possible that perturbed lysosome positioning might also influence specific pools of mTORC2 and AKT, as recently demonstrated (Jia & Bonifacino, 2019). Accordingly, AKT activity modulated the lysosomal membrane dynamics during autophagy (Arias et al, 2015). We and others speculate that there may exist unidentified substrates of MALT1, which link its protease activity directly to mTOR activation (Juilland & Thome, 2018; Thys et al, 2018). This may also rationalize the need for constitutive MALT1 activity in GSCs, as mTOR is constantly functioning in these cells (Galan‐Moya et al, 2011). Moreover, it was suggested that down‐regulation of lysosomes reduces recycling of receptors, including EGFR, which allows signaling to continue even in unfavorable niche where GSCs often reside and/or travel (Shingu et al, 2016). Less turnover of EGFR may also explain increased mTOR activation despite lysosomal down‐regulation (Li et al, 2016). In addition, AKT can be central to balance between proliferation and apoptosis, by integrating multiple signaling networks besides mTOR in GBM. One hypothesis is that mTOR inhibition and/or dissociation from endo‐lysosomes originate from lack of processing of unknown MALT1 substrates and is then exacerbated once homeostasis is disrupted.

How is QKI involved? Based on our data, we hypothesize that MALT1 sequesters QKI to prevent it from carrying out its RNA‐binding function. Interestingly, MALT1 is already known to regulate other RNA‐binding proteins Regnase‐1/ZC3H12A, Roquin‐1/RC3H1, and Roquin‐2/RC3H2 (Uehata et al, 2013; Jeltsch et al, 2014). We propose that upon MALT1 inhibition QKI is released and free to bind its RNA‐binding partners. QKI has already been shown to bind directly to lysosomal RNAs in progenitor cells (Shingu et al, 2016). It is thus tempting to speculate that QKI‐dependent stabilization of lysosomal RNAs would preference the system toward more translation of these genes upon MALT1 inhibition, leading in turn to dysregulated endo‐lysosomal protein expression and LMP. Indeed, our RNA‐sequencing data suggest changes in translation and RNA biology upon MPZ treatment; however, further study is needed to validate whether there is increased QKI binding to lysosomal RNAs upon MALT1 inhibition. Notably, QKI‐dependent lysosomal increase appears to be a post‐transcriptional effect, independent of TFEB. As such, we propose a method of dual lysosomal control in GSCs whereby transcriptional biogenesis is tightly checked by known mTOR/TFEB pathway, and MALT1 acts on post‐transcriptional regulation by isolating QKI from RNAs.

These findings place MALT1 as a new druggable target operating in non‐immune cancer cells and involved in endo‐lysosome homeostasis. Lysosomal homeostasis appears vital for glioblastoma cell survival and thus presents an intriguing axis for new therapeutic strategies in GBM.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to sample collection for diagnostic purposes. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of Sainte Anne Hospital, Paris, France, and Laennec Hospital, Nantes, France, and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Protocol. Animal procedures were conducted as outlined by the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes (ETS 123) and approved by the French Government (APAFIS#2016‐2015092917067009).

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) analysis

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) was explored via the Gliovis platform (http://gliovis.bioinfo.cnio.es/) (Bowman et al, 2007). RNAseq databases (155 patients) were used to interrogate data related to MALT1 and QKI expression (levels of RNA, probability of survival, correlation with QKI expression). Optimal cutoffs were set. All subtypes were included and histology was the only selective criteria.

Cell culture, siRNA and DNA transfection, and lentiviral transduction

GBM patient‐derived cells with stem‐like properties (GSCs) were isolated as previously described (Treps et al, 2016; Harford‐Wright et al, 2017). GSC#1 (mesenchymal, 68‐year‐old male), GSC#4 (mesenchymal, 76‐year‐old female), GSC#9 (classical, 68‐year‐old female), and GSC#12 (neural, 59‐year‐old male) were cultured as spheroids in NS34 medium (DMEM‐F12, with N2, G5, and B27 supplements, glutamax, and antibiotics). In order to induce differentiation, GSCs were grown in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), glutamax, and antibiotics, for at least 2 weeks. Differentiation of sister cells (DGC) was monitored through their morphology and NESTIN and/or SOX2 loss of expression. Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hCMEC/D3, a gift from PO Couraud, Institut Cochin, Paris, France) and HEK‐293T cells (ATCC) were cultured as previously described (Treps et al, 2016). Human fetal astrocytes SVG‐p12 (ATCC) and human neuronal‐like cells SK‐N‐SH (ATCC) were cultured in MEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and antibiotics.

Stealth non‐silencing control duplexes (low‐GC 12935200, Life Technologies), and small interfering RNA duplexes (Stealth RNAi, Life Technologies) were transfected using RNAiMAX lipofectamine (Life Technologies). The following duplexes targeting the respective human genes were as follows: CAGCAUUCUGGAUUGGCAAAUGGAA (MALT1), CCTTGAGTATCCTATTGAACCTAGT (QKI), UCAGAUGAGAGUAAUUUCUCUGAAA and GGGCUCCUCCUUUGCCACCAGAUCU (BCL10), CCCUUUGCGUGAAAGCCCAAGAGAU, ACAUCACAGGGAGUGUGACACUUAA, and GACAAGGGACCAGAUGGACUGUCGU (CARD10), AGACGAAGGUUCAACAUCA (TFEB), CCACTCTGTGAGGAATGCACAGATA (BECN1).

pFRT/FLAG/HA‐DEST QKI was purchased from Addgene and was subsequently cloned into a pCDH1‐MSCV‐EF1α‐GreenPuro vector (SBI). pMSCV‐MALT1A‐WT and pMSCV‐MALT1A‐E397A were a gift from Daniel Krappmann (German Research Center for Environmental Health, Neuherberg, Germany). pMSCV‐MALT1A‐WT was subsequently mutated to C464A. Lentiviral GFP‐expressing GIPZ shMALT1 (V2LHS_84221 TATAATAACCCATATACTC and V3LHS378343 TCTTCTGCAACTTCATCCA) or non‐silencing short hairpin control (shc) was purchased from Open Biosystems. Lentiviral particles were obtained from psPAX2 and pVSVg co‐transfected HEK‐293T cells and infected as previously described (Dubois et al, 2014). pFRT/FLAG/HA‐DEST QKI was a gift from Thomas Tuschl (Landthaler et al, 2008); pRluc‐LC3wt and pRluc‐LC3BG120A were a gift from Marja Jaattela (Farkas & Jaattela, 2017). They were introduced in GSCs using Neon electroporation system according to manufacturer's instructions (Life technologies).

Antibodies and reagents

Cathepsin inhibitor 1 was purchased from SelleckChem, rapamycin from Tocris Bioscience, and mepazine from Chembridge. Bafilomycin A1, cycloheximide, chloroquine, phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), pepstatin A, fluphenazine, cyamemazine, chlorpromazine, pipotiazine, alimemazine, promethazine, and doxylamine were all from Sigma‐Aldrich. Z‐VRPR‐FMK was purchased from Enzo Life Sciences. Q‐VD‐OPh and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha (TNFα) were obtained from R&D Systems. Ionomycin was purchased from Calbiochem. The following primary antibodies were used: NESTIN (Millipore MAB5326), SOX2 (Millipore AB5603), GAPDH (Santa Cruz SC‐25778 and SC‐32233), TUBULIN (Santa Cruz SC‐8035), MALT1 (Santa Cruz SC‐46677), LAMP2 (Santa Cruz SC‐18822), BCL10 (Santa Cruz SC‐13153), BCL10 (Santa Cruz SC‐5273), CYLD (Santa Cruz SC‐137139), HOIL1 (Santa Cruz SC‐393754), QKI (Santa Cruz SC‐517305), PARP (Santa Cruz SC‐8007), IκBα (CST 9242), p‐S32/S36‐IκBα (CST 9246), P62 (CST 5114), P62 (CST 88588), mTOR (CST 2983), p‐S473‐AKT (CST 4060), AKT (CST 9272), p‐S235/S236‐S6 (CST 2211), p‐T183/Y185‐JNK (CST 9255), JNK (CST 9258), p‐S757‐ULK1 (CST 6888), LC3B (CST 3868), p‐T37/T46‐4E‐BP1 (CST 2855), p‐T70‐4E‐BP1 (CST 9455), p‐S65‐4E‐BP1 (CST 9451), 4E‐BP1 (CST 9644), eIF4E (CST 2067), TOM20 (CST 42406), p‐T421/S424‐p70S6K (CST 9204), p70S6K (CST 14130), EEA1 (BD Bioscience 610456), CTSD (BD Bioscience 610800), PEX1 (BD Bioscience 611719), PECAM (BD Bioscience 557355), TFEB (Bethyl A303‐673A), PDI (Abcam ab2792), GM130 (Abcam ab52649), QKI (Atlas HPA019123), CTSD (Atlas HPA063001), ULK1 (Sigma A7481), and FLAG (Sigma F1804). HRP‐conjugated secondary antibodies (anti‐rabbit, mouse Ig, mouse IgG1, mouse IgG2a, and mouse IgG2b) were purchased from Southern Biotech. Alexa‐conjugated secondary antibodies were from Life Technologies.

Tumorsphere formation

To analyze tumorsphere formation, GSCs (100/μl) were seeded in triplicate in NS34 media as previously described (Harford‐Wright et al, 2017). Cells were dissociated manually each day to reduce aggregation influence and maintained at 37°C 5% CO2 until day 5 (day 4 for siRNA). Tumorspheres per field of view (fov) were calculated by counting the total number of tumorspheres in 5 random fov for each well. The mean of each condition was obtained from the triplicates of three independent experiments.

Limiting dilution assays

In order to evaluate the self‐renewal of GSCs, limited dilution assays (LDA) were performed as previously described (Tropepe et al, 1999). GSCs were plated in a 96‐well plate using serial dilution ranging from 2,000 to 1 cell/well with 8 replicates per dilution and treated as indicated. After 14 days, each well was binarily evaluated for tumorsphere formation. Stemness frequency was then calculated using ELDA software (Hu & Smyth, 2009). The mean stemness frequency for each treatment was calculated by averaging across two independent experiments.

Cell viability

Cell viability was measured using Cell TiterGlo luminescent cell viability assay, according to the manufacturers’ protocol. Briefly, cells were seeded at 5,000 cells per well in triplicate per indicated treatment. Two days later, 100 μl of Cell TiterGlo reagent was added to each condition, cells were shaken vigorously, using an orbital shaker, to aid in their lysis, and then, luminescence was measured on a FluStar Optima plate reader (BMG).

ELISA

10 × 106 GSCs were cultured with 20 μM MPZ or DMSO and culture media was collected at 8 h, centrifuged, and filtered. Alternatively, cells were transfected with sic or siMALT1 and supernatants were collected on day 3 post‐transfection, centrifuged, and filtered. Human CTSD ELISA (Sigma) was performed on the culture media according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Animal procedures

Tumor inoculation was performed on female Balb/C nude mice aged 6–7 weeks, as described previously (Harford‐Wright et al, 2017). Animals were randomly assigned to each group and group‐housed in specific pathogen‐free (SPF) conditions at 24°C on a 12‐h day–night cycle. At all times, animals were allowed access to standard rodent pellets and water ad libitum. Mice were subcutaneously injected in each flank with 106 GSC#9 in 100 μl of PBS and growth factor‐free Matrigel. Once tumors were palpable, mice were injected intraperitoneally daily with MPZ (8 mg/kg) or vehicle (DMSO) for two consecutive weeks, based on previous reports (Nagel et al, 2012; McGuire et al, 2014). Tumor size was measured daily during treatment and for 1 week following treatment withdrawal, with calipers and tumor volume calculated using the following equation (width2 × length)/2.

Luciferase assays

Rluc‐LC3B luciferase assay was performed as previously described (Farkas & Jaattela, 2017). Briefly, GSC#9 was transfected with 1 μg plasmid using a Neon Transfection System. 24 h later, cells were treated for 4 h with DMSO or MPZ and then assayed using Dual‐Glo Luciferase assay system according to the manufacturers’ guidelines. Luminescence was measured on a FluStarOptima plate reader.

Flow cytometry

For EdU analysis, cells we incubated with EdU (10 μM) for 2 h followed by fixation and Click‐it reaction according to the manufacturers’ protocol. For propidium iodide (PI) staining, cells were incubated for 15 min at room temperature with PI (100 μg/ml) following treatment according to manufacturer's protocol. Flow cytometry analyses were performed on FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, Cytocell, SFR Francois Bonamy, Nantes, France) and processed using FlowJo software.

Immunostaining

After treatment, cells were seeded onto poly‐lysine slides, fixed for 10 min with 4% PFA diluted in PBS, permeabilized in 0.04% Triton X‐100, and blocked with PBS–BSA 4% prior to 1 h primary antibody incubation. After PBS washes, cells were incubated with AlexaFluor‐conjugated secondary antibodies for 30 min. Next, cells were incubated with DAPI for 10 min and mounted with prolong gold anti‐fade mounting medium. For Lysotracker Red DND‐99 staining, cells were incubated with 50 nM Lysotracker during the last 30 min of treatment, and cells were fixed for 10 min in 4% PFA. To monitor changes in lysosomal enzyme activity, DQ‐ovalbumin assay was performed, as previously described (Ebner et al, 2018). Cells were incubated with 10 μg/ml DQ‐ovalbumin for 1 h at the end of treatment. Cells were then fixed for 10 min in 4% PFA. For transferrin uptake assay, following treatment, cells were washed in medium and incubated with Alexa596‐conjugated transferrin (25 μg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were then acid‐washed for 40 s and fixed for 10 min in 4% PFA. Mouse tissue sections, 7 μm thickness, were obtained after cryosectioning of xenograft tumor embedded in OCT (Leica cryostat, SC3M facility, SFR Francois Bonamy, Nantes, France). Mouse tissue sections and human GBM samples from patients (IRCNA tumor library IRCNA, CHU Nantes, Integrated Center for Oncology, ICO, St. Herblain, France) were stained as followed. Sections were fixed 20 min in 4% PFA, permeabilized 10 min with PBS–Triton 0.2%, and blocked with 4% PBS–BSA 2 h prior to staining. Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C. All images were acquired on confocal Nikon A1 Rsi, using a 60× oil‐immersion lens (Nikon Excellence Center, MicroPicell, SFR Francois Bonamy, Nantes, France). Structure illumination microscopy (SIM) images were acquired with a Nikon N‐SIM microscope. Z‐stacks of 0.12 μm were performed using a 100× oil‐immersion lens with a 1.49 aperture and reconstructed in 3D using the NIS‐Element Software. All images were analyzed and quantified using the ImageJ software.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Cells were harvested with cold PBS followed by cellular lysis in TNT lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X‐100, 1% Igepal, 2 mM EDTA, supplemented with protease inhibitor) for 30 min on ice. Samples were centrifuged at 8,000 g to remove insoluble fraction. Tissue samples were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer for 2 h under agitation, following homogenization with mortar and pestle. Lysates were cleared in centrifuge at max speed for 30 min. Cytosol and nuclei separation were performed as previously described (Dubois et al, 2014). Briefly, cells were lysed in Buffer A (HEPES 10 mM, KCl 10 mM, EDTA 0.1 mM, EGTA 0.1 mM, DTT 1 mM, Na3VO4 1 mM, plus protease inhibitor) on ice for 5 min and then Buffer A + 10% Igepal was added for 5 min. Samples were centrifuged at 1,000 g for 3 min. Soluble fraction was cleared at 8,000 g. Immunoprecipitation was performed as previously described (Dubois et al, 2014). Briefly, cells were lysed in TNT lysis buffer for 30 min and cleared by centrifugation at 8,000 g. Samples were precleared by a 30‐min incubation with Protein G agarose and then incubated for 2 h at 4°C with Protein G agarose and 5 μg of indicated antibodies. Protein concentrations were determined by BCA. Equal amount of 5–10 μg proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were revealed using a chemiluminescent HRP substrate and visualized using the Fusion imaging system.

Electron microscopy

After treatment, 1 volume of warm 2.5% glutaraldehyde (0.1M PB buffer, pH 7.2, 37°C) was added to 1 volume of cell suspension for 5 min, RT. Fixative was removed by centrifugation, and cells were treated 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h, RT. Samples were then stored at 4°C in 1% paraformaldehyde until processed. After washes (10 min × 3), cells are post‐fixed by 1% OsO4/1.5% K3[Fe(CN)6] for 30 min following washed by ddH2O 10 min × 3, then dehydrated by 50, 70, 80, 90, 100% ethanol, 100% ethanol/100% acetone (1:1) for 5 min, 100% acetone for 3 min. Cells were infiltrated by 100% acetone/pure resin 1:1, 1:2, 1:3 for 1 h, pure resin overnight, pure resin for 1 h, then cells were embedded in the pure resin and polymerized at 60°C for 48 h. 70‐nm sections were stained by uranyl acetate and lead citrate then observed under TEM at 80 kV (Technology Center for Protein Sciences, School of Life Sciences, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China).

RNAseq analysis