Abstract

Objective:

Ectopic Cushing’s syndrome secondary to thymic carcinoid is a rare disorder that may be difficult to diagnose and manage.

Methods:

We describe a case of severe Cushing’s syndrome secondary to a large adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) producing thymic carcinoid in a patient with history of primary hyperaldosteronism.

Results:

A 43-year-old female with a 20-year history of an aldosterone-secreting adrenocortical adenoma status post right adrenalectomy presented with acute onset of proximal muscle weakness, swelling, facial hirsutism, and severe hypokalemia. Ectopic Cushing’s Syndrome was suspected based on the sudden symptom onset and markedly elevated 24-hr urine cortisol and ACTH levels. MRI revealed an empty pituitary sella and a large (7.3 cm) mediastinal mass visible on chest CT. The mass was resected by video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, resulting in resolution of symptoms and cortisol levels. Pathology assessment confirmed well-differentiated thymic carcinoid with positive ACTH staining.

Conclusion:

The case highlights clinical features, challenges in diagnostic work up, treatment modalities, and associated endocrine findings in a thymic carcinoid abutting the heart and presenting with ectopic ACTH secretion.

Keywords: Thymic carcinoid, ectopic Cushing’s syndrome, EAS, ACTH, neuroendocrine carcinoma of thymus, empty sella, hyperaldosteronism

Introduction

Thymic carcinoid tumors associated with ectopic ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome (EAS) are exceedingly rare. Approximately 90% of patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome arise from pituitary tumors, and the remaining are caused by non-pituitary tumors including small cell lung carcinomas, pancreatic or bronchial neuroendocrine tumors, medullary thyroid cancer, and pheochromocytomas (1). Thymic carcinoid tumors account for about 5% of ectopic ACTH secretion (1–3).

Thymic carcinoid tumors tend to be aggressive with poor clinical prognosis and may be associated with symptoms of hormone hypersecretion. Approximately 35% of thymic carcinoid tumors present with endocrinopathies and paraneoplastic syndromes, including Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly or SIADH (4). Here we report thymic carcinoid presenting with EAS with history of aldosterone-secreting adrenocortical tumor and incidental discovery of an empty sella on pituitary MRI.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old female presented with three weeks of generalized weakness and swelling in her lower extremities. She had been otherwise healthy except for a history of a 2-cm right aldosterone-secreting adrenal adenoma, for which she underwent right adrenalectomy 20 years prior. Hypertension resolved after adrenalectomy and she did not require medications. A detailed three generational family history revealed no significant medical problems.

On presentation, her symptoms included one month of mood swings, insomnia, generalized pruritic rash, prominently increased facial hair, and acute darkening of skin in sun-exposed areas including the face, neck, and upper chest. Physical examination was remarkable for elevated blood pressure (157/88 mmHg), dorsocervical subcutaneous fat pad, hirsutism, proximal muscle weakness, and acneiform-like rash on the upper chest, abdomen, and back. Patient was not taking medication at the time of presentation.

Laboratory evaluation revealed severe hypokalemia (2.6 mEq/L), hyperglycemia (223 mg/dL), significantly elevated urinary free cortisol (13,000 µg/24 hours), and elevated plasma ACTH levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory evaluation at baseline and at follow up.

| Lab | Reference range |

Baseline | 1 week after initiation of ketoconazole |

7 weeks after surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACTH, pg/mL | 6-50 | 396 | 25.9 | |

| Plasma cortisol, µg/dL | 6.2-19.4 | 95.2 | ||

| 24-hour urinary free cortisol, µg/24 hours | 4.0-50.0 | 13,000 | 909 | 9 |

| Late night salivary cortisol (10 PM-1AM), µg/dL | ≤0.09 | <0.01 | ||

| Potassium, mEq/L | 3.5-5.2 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 4.6 |

| Glucose, mg/dL | 70-99 | 233 |

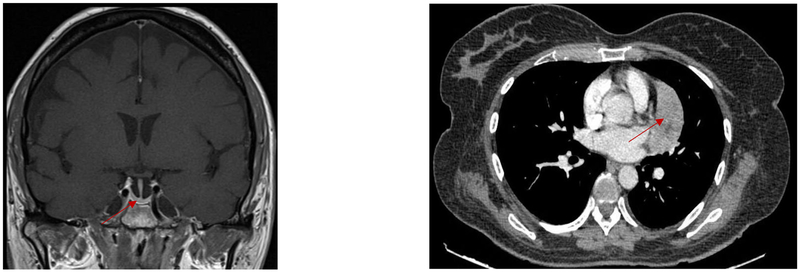

Pituitary magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an empty sella (Figure 1). Given a strong suspicion for an ectopic source of ACTH production, computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen and pelvis revealed a 7.1 × 3.1 × 7.3 cm heterogeneous mediastinal mass, inseparable from the left cardiac ventricle.

Figure 1.

Left panel: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) pituitary with empty sella (red arrow). Right panel: computer tomography (CT) chest with 7.3 cm mediastinal mass (red arrow).

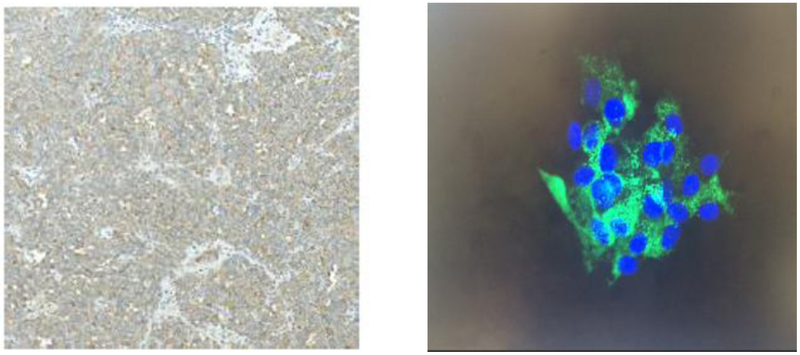

Ketoconazole 200 mg twice daily was initiated, and was titrated up to 400 mg twice a day with subsequent improvement in 24-hr urine cortisol to 909 µg/24 hours. Hyperglycemia was managed with insulin. Pre-operative hospital course included treatment for urinary tract infection, large doses of potassium repletion, and venous thromboembolism prophylaxis with subcutaneous heparin. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery was undertaken with complete resection of a well encapsulated tumor. Pathology evaluation revealed well-differentiated thymic carcinoid with involved margins and extensive angiolymphatic invasion (Stage IIa, pT2Nx). On immunohistochemistry ACTH staining was diffusely positive (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Left panel: Diffusively positive ACTH staining of tissue from mediastinal mass. Right panel: Positive immunostaining of isolated cell culture. Green: ACTH; blue: DAPI (4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole).

After tumor resection, there was clinical improvement and ketoconazole was discontinued, as were insulin and potassium supplementation. Immediately after surgery, hydrocortisone 100 mg intravenously was administered. Hydrocortisone dose was quickly tapered down to an oral dose of 10 mg with breakfast and 5 mg with lunch. Morning pre-dose cortisol levels were adequate and there were no signs or symptoms of adrenal insufficiency after discontinuation of hydrocortisone. Nearly three weeks after operation, the patient lost weight, re-gained strength, and rash and acne diminished. At the one-month post-operative follow-up, ACTH level was 25.9 pg/mL. Hypercortisolemia resolved as evidenced by a 24-hr urine cortisol of 9 µg/24 hours and two suppressed (<0.01 µg/dL) late-night salivary cortisol values (Table 1). Three months after surgery, CT, MRI, and octreotide scans did not reveal tumor remnant or recurrence.

Discussion

Though adrenal adenomas co-secreting cortisol and aldosterone have been reported (5), this is a unique report of a combined ectopic ACTH dependent Cushing’s syndrome (EAS), primary hyperaldosteronism, and empty sella. Clinical presentation that includes abrupt onset, pronounced symptoms, and severe hypokalemia can be an important clue alluding to the presence of ectopic source of ACTH (1,6). However, ectopic tumors can be difficult to identify, and up to 19% of cases of EAS may not have tumor localization despite extensive diagnostic work-up (1,2,7).

Diagnosis of EAS relies on dynamic testing including inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS) and high dose dexamethasone suppression, as well as localizing imaging modalities. IPSS is the gold standard for distinguishing pituitary versus ectopic ACTH sources, especially if MRI of the pituitary reveals an adenoma less than 6 mm in diameter (8). In our case, pituitary MRI revealed an empty sella and clinical presentation was consistent with an ectopic ACTH source. As markedly elevated ACTH levels also point to a diagnosis of EAS (9), we did not pursue IPSS and proceeded to perform a CT of the chest which revealed a 7 cm mediastinal mass.

Empty sella may theoretically have occurred due to pituitary hypoplasia as a result of strong negative glucocorticoid feedback from EAS. However, the presence of an empty sella does not preclude the diagnosis of pituitary Cushing’s disease and appropriate testing should be pursued if the suspicion for a pituitary ACTH source is high (10,11).

The mainstay of treatment for thymic carcinoid tumors is surgical resection (12). Our patient achieved excellent response with video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS), including complete clinical response and no evidence of residual tumor three months after surgery. Comparison of long term outcomes for VATS and median sternotomy in treating thymic carcinoid tumor is lacking, but long term effectiveness has been reported in treatment of early stage thymoma (13). The early favorable therapeutic response of this patient favors the use of VATS as a safe and effective surgical approach by an experienced surgeon, even in the setting of a very large tumor.

Pre-operative medical management of Cushing’s syndrome is crucial to prevent life-threatening complications. Treatment options include steroidogenesis inhibitors such as ketoconazole or metyrapone, and glucocorticoid receptor antagonists such as mifepristone, which can be used solely or in combination (14). Molecular targeted therapies studied as a potential therapeutic option include gefitinib targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and R-roscovitine targeting the ACTH secreting tumor (15–17).

Urinary cortisol levels improved markedly shortly after initiation of ketoconazole monotherapy; however, symptoms of hypokalemia and hyperglycemia persisted.

Thymic carcinoid, especially associated with EAS, shows worse prognosis and has a higher chance of recurrence compared to other neuroendocrine tumors (1). Despite the excellent surgical response, our patient remains at high risk for tumor recurrence.

Conclusion

EAS is a rare form of Cushing’s syndrome that can present with suggestive clinical findings and unique endocrine gland associations as presented here. Though medical management is an important temporizing measure, medical monotherapy is seldom effective in disease control. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment and VATS may be a less invasive and preferred approach.

References

- 1.Ilias I, Torpy DJ, Pacak K, Mullen N, Wesley RA, Nieman LK. Cushing’s syndrome due to ectopic corticotropin secretion: twenty years’ experience at the National Institutes of Health. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4955–4962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Isidori AM, Kaltsas GA, Pozza C, et al. The ectopic adrenocorticotropin syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, management, and long-term follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:371–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aniszewski JP, Young WF Jr., Thompson GB, Grant CS, van Heerden JA. Cushing syndrome due to ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion. World J Surg 2001;25:934–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaur P, Leary C, Yao JC. Thymic neuroendocrine tumors: a SEER database analysis of 160 patients. Ann Surgery. 2010;251:1117–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Honda T, Nakamura T, Saito Y, Ohyama Y, Sumino H, Kurabayashi M. Combined primary aldosteronism and preclinical Cushing’s syndrome: an unusual case presentation of adrenal adenoma. Hypertens Res 2001;24:723–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salgado LR, Fragoso MC, Knoepfelmacher M, et al. Ectopic ACTH syndrome: our experience with 25 cases. Eur J Endocrinol 2006;155:725–733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ejaz S, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Busaidy NL, et al. Cushing syndrome secondary to ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion: the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer. 2011;117:4381–4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacroix A, Feelders RA, Stratakis CA, Nieman LK. Cushing’s syndrome. Lancet 2015;386:913–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhn JM, Proeschel MF, Seurin DJ, Bertagna XY, Luton JP, Girard FL. Comparative assessment of ACTH and lipotropin plasma levels in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with Cushing’s syndrome: a study of 210 cases. Am J Med 1989;86:678–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manavela MP, Goodall CM, Katz SB, Moncet D, Bruno OD. The association of Cushing’s disease and primary empty sella turcica. Pituitary. 2001;4:145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta GU, Bakhtian KD, Oldfield EH. Effect of primary empty sella syndrome on pituitary surgery for Cushing’s disease. J Neurosurg 2014;121:518–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kulke MH, Shah MH, Benson AB 3rd, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2015;13:78–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maniscalco P, Tamburini N, Quarantotto F, Grossi W, Garelli E, Cavallesco G. Long-term outcome for early stage thymoma: comparison between thoracoscopic and open approaches. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;63:201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corcuff JB, Young J, Masquefa-Giraud P, Chanson P, Baudin E, Tabarin A. Rapid control of severe neoplastic hypercortisolism with metyrapone and ketoconazole. Eur J Endocrinol 2015;172:473–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukuoka H, Cooper O, Ben-Shlomo A, et al. EGFR as a therapeutic target for human, canine, and mouse ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas. J Clin Invest 2011;121:4712–4721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu NA, Araki T, Cuevas-Ramos D, et al. Cyclin E-mediated human proopiomelanocortin regulation as a therapeutic target for Cushing disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:2557–2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Araki T, Liu NA, Tone Y, et al. E2F1-mediated human POMC expression in ectopic Cushing’s syndrome. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2016;23:857–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]