Abstract

Neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), are prevalent among the elderly. Small GTPases of the Ras superfamily are essential regulators of intracellular trafficking and signal transduction. In this study, we develop a targeted quantification method for small GTPase proteins, where the method involves scheduled multiple-reaction monitoring analysis and the use of synthetic stable isotope-labeled peptides as internal standards or surrogate standards. We further applied this method to examine the altered expression of small GTPase proteins in post-mortem frontal cortex tissues from AD patients with different degrees of disease severity. We were able to achieve sensitive and reproducible quantifications of 80 small GTPases in brain tissue samples from 15 patients. Our results revealed substantial up-regulations of several synaptic GTPases, i.e., RAB3A/C, RAB4A/B, and RAB27B, in tissues from patients with higher degrees of AD pathology, suggesting that aberrant synaptic trafficking may modulate the progression of AD. The method should be generally applicable for high-throughput targeted quantification of small GTPase proteins in other tissue and cellular samples.

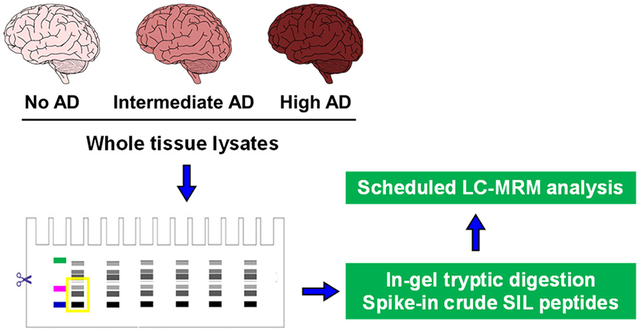

Graphical Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is among the most common neurodegenerative disorders and is a leading cause of dementia in the elderly.1 In the United States, AD affects approximately 10% of people with ages over 65 and constitutes the fifth leading cause of death in this population.2 The hallmarks of AD pathology in the brain include synapse loss, the accumulation of extracellular β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques, and twisted strands of the hyper-phosphorylated tau protein (neurofibrillary tangles) inside neurons, which promote neuronal death and ultimately dementia.3 As region-specific neurodegenerative disorders, AD can lead to neuronal loss that is predominantly found in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus, where the cerebral cortex can be further divided into the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes.4

Recent advances in quantitative proteomics have enabled high-throughput assessment of proteomic alterations accompanied by early development and progression of AD in various sample types or brain regions, including temporal neocortex,5 cerebral cortex,6 cerebrospinal fluids,7,8 hippocampus,9,10 frontal cortex,11–13 and anterior cingulate gyrus.14 Very recently, McKetney et al.15 reported a proteomic resource encompassing nine anatomically distinct sections from post-mortem brain tissues of AD patients. Moreover, targeted proteomic methods have been employed for the validation of biomarkers for AD.8,16

Small GTPases of the Ras superfamily are essential regulators of intracellular trafficking and signal transduction; therefore, they may serve as potential therapeutic targets.17 A growing body of literature revealed the importance of Rab small GTPases as crucial synaptic signaling modules in the brain.18–20 RAB7A and RAB35 regulate secretion and endolysosomal degradation of tau protein, respectively.21,22 Moreover, RAB6A is among the protein targets of 16 hub genes associated with metastable subproteome of AD,23 and RAB6 showed elevated expression in the temporal cortex, but not hippocampi of AD brains compared to nondemented controls.24 In addition, the mRNA levels of RAB4, RAB5, and RAB7 genes were up-regulated in the hippocampal tissues from individuals with AD.25 Augmented mRNA expressions of RAB4, RAB5, RAB7, and RAB27 genes were also observed in the basal forebrain of AD patients.26 Apart from Rab GTPases, Arf and Rho GTPases also assume important roles in the regulation of membrane dynamics and trafficking in neuronal cells.27 Given the importance of synaptic trafficking in neurodegenerative diseases, we reason that a comprehensive investigation about the association of small GTPase protein expression with AD progression may improve our understanding of disease etiology and lead to the identification of potential molecular targets for the therapeutic intervention of AD.

We recently developed a scheduled multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM)-based quantitative proteomic method, combined with metabolic labeling using SILAC (stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture), for high-throughput quantification of the small GTPase proteome in cultured human cells.28–30 In the current study, we set out to adapt the method to enable the quantification of these proteins in human tissue samples that are not amenable to metabolic labeling. In particular, we present a multiplexed and high-throughput targeted quantitative proteomic approach, involving the use of MRM and crude stable isotope-labeled (SIL) peptides, for the assessment of the small GTPase proteome in human tissues. We also apply the method to examine the altered expression of small GTPases in the frontal cortex region of post-mortem brain tissue samples from individuals with different stages of AD pathology.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

MRM Library Construction.

We recently established a Skyline spectral library for the Ras superfamily of small GTPases based on in-house shotgun proteomic data.28 On the basis of that library and an online targeted proteomic experiment design tool Picky (https://picky.mdc-berlin.de),31 we developed a new version of MRM spectral library that includes 389 tryptic peptides derived from 148 small GTPase proteins, representing 138 unique gene IDs and containing a total of 1635 MRM transitions. In this vein, up to three unique tryptic peptides with a maximum of 25 amino acids in length and without miscleavage (except for lysine and arginine residues preceding a proline) were selected for each small GTPase protein. Methionine-containing peptides were not preferred but were chosen when there was no better alternative. Cysteine carbamidomethylation (+57.0 Da) was set as a fixed modification, and uniformly [15N,13C]-labeled lysine (+8.0 Da) and arginine (+10.0 Da) were incorporated as heavy-isotope labels for 144 successfully synthesized heavy peptides, giving rise to a total of 538 peptide precursors. Details of all the small GTPase peptides monitored in this study and their corresponding MRM transitions are listed in Table S1A of the Supporting Information (SI).

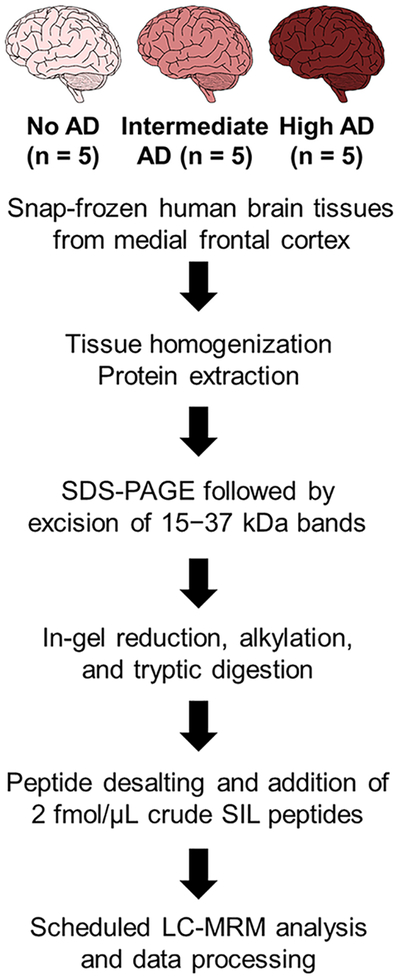

Brain Tissue Homogenization and Protein Extraction.

Snap-frozen post-mortem human brain tissues from medial frontal cortex of 15 individuals were collected by the Department of Pathology, University of Washington, and the AD cases were neuropathologically diagnosed as Braak stages 3–6. Among them, 5 each were from age-matched individuals with high (Braak stages 5–6, “high AD” group), medium (Braak stages 3–4, “intermediate AD” group), and no or low AD pathology (Braak stage 1 or none, “no AD” group). Each tissue piece (approximately 100 mg in wet weight) was homogenized in a 300-μL RIPA lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 1% NP-40), which was supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100, v/v), using a Bullet Blender (Next Advance) and 100 mg of 0.5 mm zirconium oxide beads (Next Advance). After centrifugation at 15 000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C, the supernatant was collected, and the total protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using the Quick Start Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad).

MS Sample Preparation.

Approximately 10 μg of tissue lysate was resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, followed by excision of gel bands in the molecular weight range of 15–37 kDa. The excised gel bands were cut into small pieces (1 mm3 volume), reduced with dithiothreitol, alkylated with iodoacetamide, and digested in-gel with trypsin (enzyme/substrate 1:50) at 37°C overnight.

The peptide samples were desalted, reconstituted in 40 μL of buffer A (0.08% formic acid in water), and spiked with crude SIL peptide stock solution (to a final concentration of 20 fmol/μL) prior to scheduled LC-MRM analysis. Approximately 4 μL (20 ng equiv) of sample was loaded onto a 4 cm long 150 μm inner diameter (ID) trapping column packed in house with 5 μm Reprosil-Pur C18-AQ resin (Dr. Maisch) and separated on a 25 cm long 75 μm ID fused silica column packed in-house with 3 μm Reprosil-Pur C18-AQ resin (Dr. Maisch). The LC–MS platform consisted of a Dionex UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano UPLC system coupled to a TSQ Altis triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer with a Flex nanoelectrospray ion source (Thermo Fisher). Sample elution was performed using a gradient, composed of 12–33% Buffer B (0.08% formic acid in 80% acetonitrile) in 70 min and 33–100% B in 5 min. The column was subsequently washed with 100% B for 3 min and equilibrated with 1% B for 10 min. The flow rate was maintained at 300 nL/min. The mass spectrometer was operated with an ion spray voltage of 2200 V, a capillary offset voltage of 35 V, a skimmer offset voltage of −5 V, and a capillary inlet temperature of 325°C. Both Q1 and Q3 were set at a resolution of 0.7 fwhm, and Q2 gas pressure used for peptide fragmentation was set at 1.5 mTorr. Collision energies specific to peptide precursors were calculated in Skyline (version 4.2.0). A modified iRT calculator was employed for retention time prediction and generation of the MRM method in Skyline, as described previously.28 Details of MRM quantification results are listed in Table S1B and C.

MRM Data Processing and Statistical Analysis.

The raw data were directly imported into Skyline for visualization of chromatograms of target peptides to manually determine the detectability of target peptides and to ensure the absence of matrix interference. Two parameters were considered for peak detection, i.e., scheduled retention time and dot-product (dotp) values.32 The latter indicates the similarity in distributions of relative intensities for three abundant transitions (fragment ions) for each tryptic peptide in the sample and the corresponding MS/MS in the spectral library. For those peptides where SIL peptides are available, we also calculated the ratio dot product (rdotp), which represents the similarities in distributions of relative intensities for three abundant transitions between the peptide of interest and the corresponding SIL peptide.33 All data were manually inspected to ensure that the intensity distributions of selected transitions match with the theoretical distributions of the corresponding transitions in the spectral library, with the dotp and rdotp values being greater than 0.8. The areas of peaks found in the extracted-ion chromatograms (XICs) obtained from three MRM transitions for endogenous peptides were normalized against those of SIL peptides as internal standard (IS) or surrogate standard (SS). The Skyline library and the raw files acquired from LC–MRM analyses were deposited into PeptideAtlas with the identifier number of PASS01380 (http://www.peptideatlas.org/PASS/PASS01380).

Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism 7. Differentially expressed proteins were assessed by performing Tukey’s multiple comparison test to calculate the p values among the three patient groups analyzed, i.e., no, intermediate, and high AD. The calculated p values are listed in Table S1C.

RESULTS

Targeted Proteomics Assay Development.

In the past decade, LC–MS/MS in the multiple-reaction monitoring (MRM) mode has become widely employed for sensitive, reproducible, and reliable protein quantitation in different biological matrices through multiplexed and targeted quantification of peptides.34 In MRM-based quantification, specific precursor-to-product ion transitions are monitored using a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer, generating signals for quantification. Therefore, analytical robustness of the method is highly dependent upon the selection of optimal proteotypic peptides and transitions that represent the peptides, and hence the proteins of interest.35 Recently, we established a scheduled MRM in combination with SILAC-based metabolic labeling for high-throughput quantitative profiling of small GTPases in cultured human cancer cells.28 This library was constructed on the basis of shotgun proteomic data acquired in-house, and the library contained 432 tryptic peptides originated from 131 small GTPases, which represent 113 unique gene IDs and cover approximately 75% of the human small GTPase proteome. With retention time scheduling, all targeted transitions for peptides from these small GTPases could be monitored in two LC–MRM runs with the use of a 6 min retention time window.

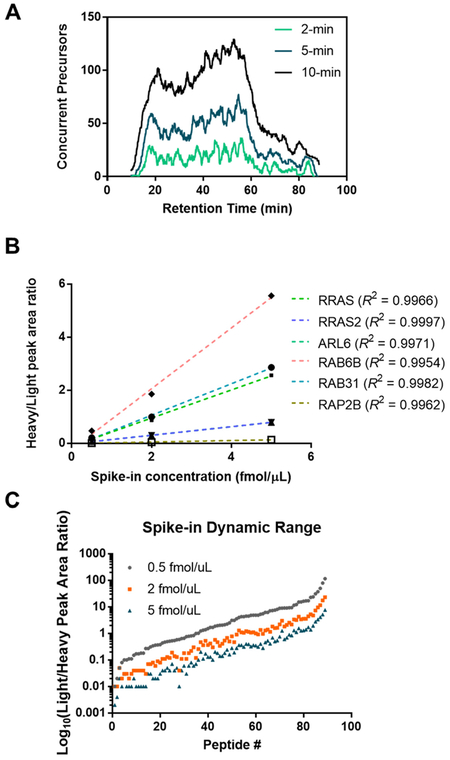

To further expand the proteome coverage of the MRM library, we employed an online targeted proteomic experiment design tool Picky (https://picky.mdc-berlin.de) to map comprehensively the candidate peptides for small GTPases of human and mouse origins.31 The peptides were chosen on the basis of their intensities as well as sequence uniqueness. With the use of this tool, we were able to modify the library to include 389 tryptic peptides from 148 proteins representing 138 unique gene IDs, which cover ~90% of the human small GTPase proteome. To the best of our knowledge, this is to date the most comprehensive MRM library for small GTPases. Because a relatively large number of transitions were monitored in a single LC run, we employed retention time scheduling using iRT.36 All targeted transitions for small GTPases can be monitored in a single LC-MS/MS run in scheduled MRM mode, with a retention time window of 4 min to yield the maximum number of concurrent transitions of ~50 (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Sensitivity, throughput, reproducibility, and accuracy of the MRM-based quantification at the peptide level. (A) The numbers of concurrent transitions scheduled in each cycle with a 2 min, 5 min, and 10 min retention time window, respectively; (B) linear regression of the peak area ratios (heavy/light) for 6 representative peptides obtained from three LC–MRM experiments with different spike-in concentrations of crude SIL standards (i.e., at nominal concentrations of 0.5, 2, and 5 fmol/μL, respectively); (C) scatter plots depicting the distribution of the peak area ratios (heavy/light) for all quantified peptides obtained from three LC–MRM experiments with different spike-in concentrations.

Analytical Performance of LC–MRM Analysis with the Use of Crude SIL Peptides.

There have been a limited number of studies in the use of crude synthetic SIL peptides in targeted quantitation, which is perhaps attributed to the relatively large variations in purities of the crude synthetic peptides.37–41 Nevertheless, owing to simplified purification, the use of crude SIL peptides allows for a larger set of candidate peptides to be incorporated into MRM assays at substantially reduced costs.

We obtained 144 synthetic peptides carrying a uniformly [13C,15N]-labeled arginine or lysine at the carboxy termini from New England Peptide, Inc., with an average purity of ~75%. These crude SIL peptides may contain impurities such as residual salts, deblocking and scavenger reagents, and truncated and partially deblocked peptides.42 Thus, we first evaluated, by employing MRM analysis, the analytical performance of the method with the use of crude SIL peptides. In particular, we confirmed the absence of isotopic interference in MRM transitions monitored for any of the SIL peptides (Figure S1). In addition, we detected 114 out of 144 crude SIL peptides in a single LC–MRM run (Figure S2A), with the signal intensities for these peptides spanning 3 orders of magnitude (Figure S2B). The failure in detecting the remaining SIL peptides may be attributed to ion suppression resulting from matrix effects and/or low abundance of these peptides in the crude peptide pool.

Evaluation of Relative Quantitation by Crude SIL Peptides.

Next, we sought to investigate the use of crude SIL peptides in performing relative quantitation. In spite of their lower purities, crude SIL peptides can be added at an equivalent concentration to all samples, which allows for normalization across runs and facilitates correction for variations in instrument and other experimental conditions. Figure 1B displays the linear correlations for representative small GTPase peptides obtained from LC–MRM analyses with the addition of different concentrations of SIL peptides, where most peptides exhibit high linear correlation coefficients (R2 > 0.995). The results again supported the feasibility in using crude SIL peptides for relative quantitation. We further optimized the concentration of crude peptides that were spiked into the samples as internal standards. Among the three spike-in concentrations (0.5, 2, 5 fmol/μL, by assuming 100% purity), we found that the addition of 2 fmol/μL of SIL peptides could result in appropriate light/heavy ratios and dynamic range (Figures 1C and S2C, and S3). Hence, we chose 2 fmol/μL as the spike-in concentration for the crude SIL peptides in the subsequent quantification experiments.

For other library peptides without their heavy counterparts as IS, we adapted slightly from the previously reported labeled reference peptide (LRP) method and adopted the concept of RT-defined surrogate standards (SS).43 Unlike IS peptides, which exhibit nearly the same chemical and chromatographic properties as the target peptides, heavy SS peptides were chosen based upon their high signal intensities and similar chromatographic behaviors as the target peptides. Therefore, we selected 12 SS peptides that display strong MRM signals and elute in different retention time windows across the entire gradient (Figure S4). As depicted in Figure S5, we found that the SS peptides eluting at similar retention times exhibited more similar distribution in MRM signal intensity and peak area than those eluting at different retention times. Relative to existing normalization methods used in MRM-based quantitation, such as label-free and LRP method using a single peptide derived from house-keeping proteins, the use of crude SIL peptides offers a cost-effective and reliable alternative in MRM-based quantification.

Targeted Proteomic Analysis of Small GTPases in AD Brain Tissue Samples.

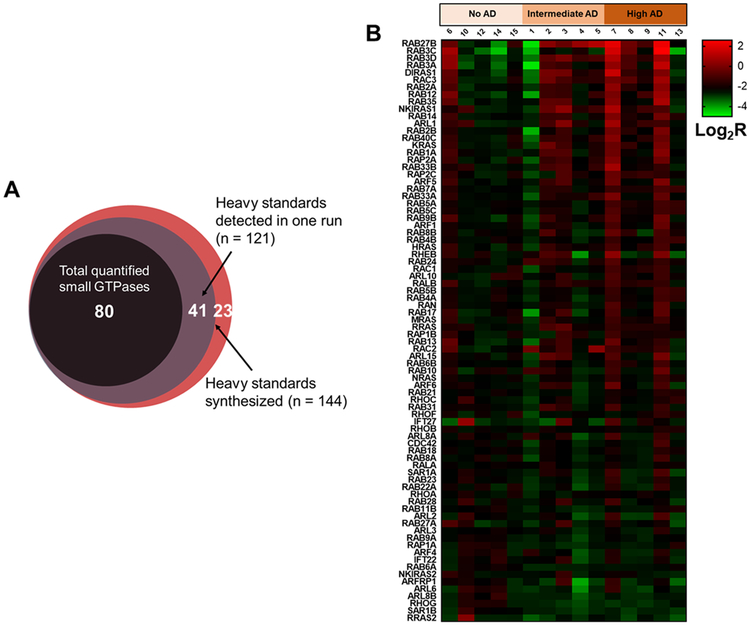

To explore the potential roles of small GTPases in AD progression, we applied the established MRM assay to assess the differential expression of small GTPases in the frontal cortex region of post-mortem brain tissue samples with different stages of AD pathology (Figure 2). In total, we were able to quantify reproducibly more than 80 small GTPases in 15 brain tissue samples (Figure 3A, Table S1B and C). As the availability of such clinical materials for analysis is often limited, we also demonstrated that a relatively small amount of protein input (~10 μg/sample) is sufficient to achieve a good coverage of target small GTPase proteins by using the LC–MRM method. Figure 3B shows a heat map illustrating detailed quantification results obtained for each small GTPase across the 15 brain tissues separated into three patient groups with different disease stages (no AD, intermediate AD, and high AD). For each quantified small GTPase, the results were normalized to the mean values of the control group (no AD).

Figure 2.

A schematic diagram illustrating the sample preparation workflow for LC-MRM analysis.

Figure 3.

Relative quantification of small GTPases in brain tissues obtained from Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients. (A) A Venn diagram depicting the overlap between quantified small GTPases, quantified SIL standards, and total targeted small GTPases in the library; (B) a heat map showing the relative quantification of small GTPases in post-mortem brain tissues of AD patients. Each column represents relative quantification results (in log2 scale) obtained from one biological replicate, and each row represents one small GTPase quantified, where sample codes and disease stages are labeled. The results were normalized to the mean values of the control group (no AD), and the quantified small GTPases were ranked by highest to lowest fold changes in mean of R(high AD/no AD).

Altered Expression of Small GTPases Involved with Synaptic Functions.

Vesical trafficking, which involves continuous cycles of exocytosis and endocytosis, is required for the maintenance of proper synaptic functions.44,45 By performing network analysis, Kokotos et al.46 revealed that Rab small GTPases constitute a key functional hub within the activity-dependent bulk endocytosis proteome in cerebellar granule neurons. Table S2 shows the results from network analysis of the synaptic Rab small GTPases reported in the literature.

A loss of synaptic contacts in both the neocortex and hippocampus represents one of the major neuropathological hallmarks of AD.47 Several Rab GTPases were previously determined as part of the exocytotic (RAB3A, RAB3B, RAB3C, and RAB27B) or endocytic (RAB4B, RAB5A/B,RAB10, RAB11B, and RAB14) machineries of synaptic vesicles.48 Interestingly, the LC–MRM data revealed altered expression of several synaptic small GTPases that are accompanied with the disease progression of AD, including RAB3A/C, RAB4A/B, and RAB27B (Figure 3B). Among the several highly homologous RAB3 isoforms (RAB3A, RAB3B, RAB3C, and RAB3D), RAB3A is the most abundant in the brain, where it resides on synaptic vesicles and participates in Ca2+-triggered neurotransmitter release.49 In general, these RAB3 isoforms play largely overlapping secretory functions in neurons and are crucial for synaptic integrity.50 RAB3B was not detectable by the LC–MRM method, which is likely due to its low protein abundance (Figure S6). On the basis of the LC–MRM results, we observed increased protein expression of RAB3A, RAB3C, and RAB3D in later stages of AD (Figure 3B), suggesting important, yet previously unrecognized functions of small GTPase-regulated synaptic trafficking and signaling in promoting AD progression.

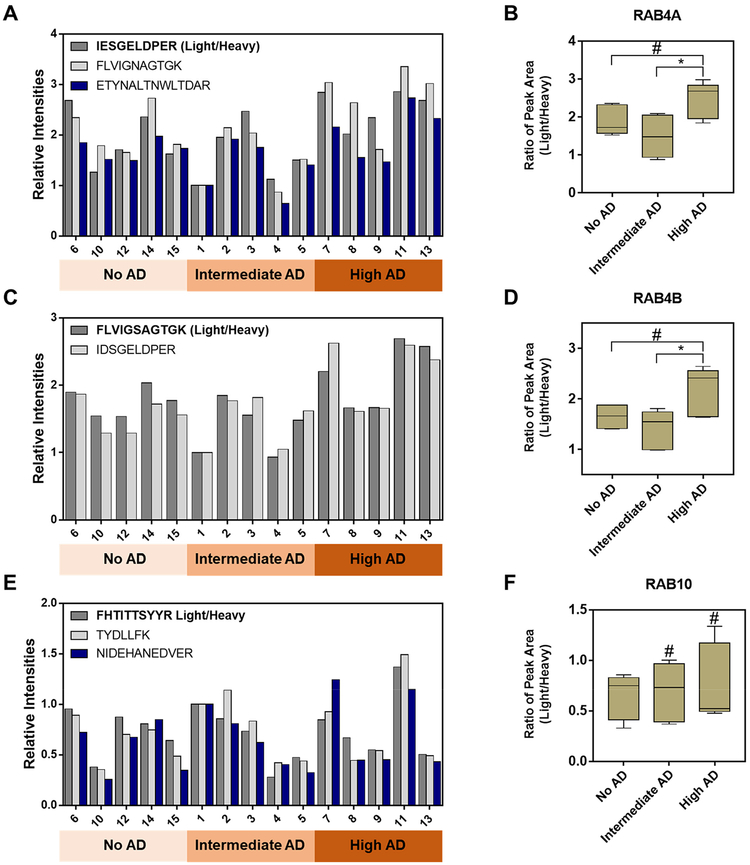

Two other synaptic small GTPases, RAB4A and RAB4B, were significantly up-regulated in the “high AD” group of patients relative to the “intermediate AD” group, though there were no significant differences between the “no AD” group and the “high AD” group (Figure 4A–D). It is of note that RAB4 was found to be up-regulated at mRNA levels in the basal forebrain and the hippocampal regions of AD brains in two independent studies.25,26 In contrast to the microarray-based studies, our MRM-based approach indicated that both isoforms of RAB4 (RAB4A and RAB4B), which are involved with synaptic functions, could bear important functions in AD progression. For other synaptic GTPases such as RAB10, there were no obvious differences in expression among the three patient groups (Figure 4E–F).

Figure 4. Representative MRM quantification results for three synaptic GTPases, RAB4A, RAB4B, and RAB10.

(A) A bar graph illustrating the MRM-based quantification results obtained from three peptides derived from RAB4A; (B) a box and whisker plot summarizing the quantification results in panel (A); (C) a bar graph illustrating the MRM-based quantification results obtained from two peptides derived from RAB4B; (D) a box and whisker plot summarizing the quantification results in panel (C); (E) a bar graph illustrating the MRM-based quantification results obtained from three peptides derived from RAB10; (F) a box and whisker plot summarizing the quantification results in panel (E). In the box and whisker plots, the horizontal bar in the box, top/bottom edges of the box, and whiskers indicate the mean, quartiles, and the maximum range, respectively. Tukey’s multiple comparison test was performed to calculate the p values (#, p > 0.05; *, 0.01 ≤ p < 0.05).

Validation of Proteomic Data by Western Blot Analysis.

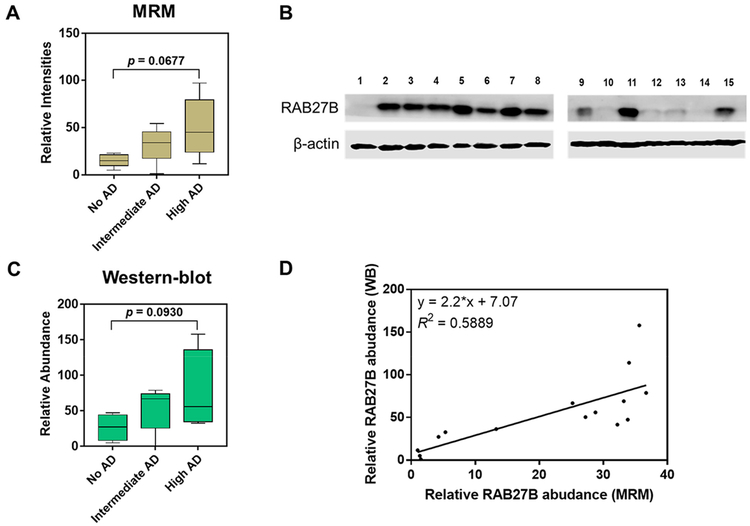

In addition to RAB3, RAB27B also plays a distinct yet overlapping role in synaptic vesicle trafficking and modulates Ca2+-dependent exocytosis.48 Interestingly, we observed that RAB27B was substantially up-regulated in higher AD stages, although the difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5A). By evaluating the three MRM transitions monitored for each peptide precursor, we observed that the endogenous and stable isotope-labeled peptide of LLALGDSGVGK showed dotp values of 0.93–0.97 and rdotp values of 0.99–1.00, and the endogenous peptide FITTVGIDFR displayed dotp values of 0.89–0.93 (Figure S7A–C). Furthermore, the quantification results for this protein in the 15 brain tissue samples normalized by both IS and SS peptides exhibited a reasonably good linear correlation (R2 = 0.961) (Figure S7D–E). Thus, the MRM quantitation results obtained from the two normalization methods, i.e., IS-based and SS-based, were highly similar and dysregulated synaptic trafficking could play potential roles in the progression of AD.

Figure 5.

Substantial up-regulation of RAB27B in higher stages of AD. (A) A box and whisker plot summarizing the LC–MRM quantification results of the protein levels of RAB27B among the three patient groups; (B) Western blot analysis of RAB27B in the 15 human brain tissue samples; (C) a box and whisker plot summarizing the Western blot quantification results for the relative levels of RAB27B in the brain tissues of the three patient groups. In the box and whisker plots, the horizontal bar in the box, top/bottom edges of the box, and whiskers indicate the mean, quartiles, and the maximum range, respectively; (D) linear regression analysis for the quantification results obtained by Western blot (WB) and LC–MRM assay. Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was performed to calculate the p values.

To validate the proteomic results, we also performed Western blot analysis for RAB27B and found that there was a moderate correlation between the quantification data obtained from the two methods, with an R2 value 0.5889 (Figure 5B–D). These results also indicate the different dynamic ranges of the two quantification methods, where LC–MRM is superior over Western blot in revealing large fold changes in protein expression. In this vein, the dynamic ranges for targeted proteomics and Western blot were estimated to be 4–5 and 2 orders of magnitude, respectively.38 Meanwhile, the other isoform of RAB27, i.e., RAB27A did not display obvious correlation in protein abundance with AD stage. When compared to Western blot analysis, which requires the availability of antibodies that are specific for the isoforms of the protein of interest, LC–MRM provides a powerful analytical approach to differentiate protein isoforms with high sequence homology.

DISCUSSION

Potential roles of small GTPases in synaptic trafficking and modulation of neurodegeneration have been increasingly discussed recently.20 In this study, we observed a substantial up-regulation of RAB27B protein in patient brain tissue samples with higher disease stage of AD, which is in accordance with the dysregulated RAB27B in AD reported in previous proteomic and transcriptomic studies.14,15,26 Furthermore, several other synaptic GTPases, such as RAB3A/C/D and RAB4A/B, were found to be up-regulated in brain tissues with higher degree of AD pathology (Figures 3 and 4). In this vein, it is worth noting that the proteomic profiles within different brain regions are likely to alter qualitatively and/or quantitatively during aging and/or in different disease states. Thus, identification of proteins unique to each brain region that are associated with neurodegenerative processes may offer opportunities for the development of new protective and restorative therapies for neurodegenerative diseases.

The absolute quantification (AQUA), which involves the spiking of samples with high-purity (>98%) stable isotope-labeled (13C and/or 15N) peptides as internal standards (SIS), enables highly reliable and specific targeted quantification of proteins and their post-translational modifications.51 The AQUA method usually requires the generation of calibration curves by stable isotope dilution using high-purity SIS peptides and is therefore more expensive and labor-intensive. Other studies employed the LRP approach, which essentially uses MRM signals for one or more peptides derived from house-keeping proteins (e.g., GAPDH or actin) to normalize MRM signals for the targeted peptides.43,52,53 In general, the LRP-based method represents a cost-effective normalization strategy for a large number of target proteins, in which a single isotope-labeled standard peptide is used as the reference for all target peptides in an analysis.43 In the current study, we have limited the scope of the analysis to relative quantitation and data normalization based on crude SIL peptide cocktail, by avoiding the corresponding high cost for high-purity SIS peptide standards. In this regard, it is important to assess, by MRM analysis, the potential interferences from the crude SIL peptides in analyte measurements and the detectability of the SIL peptides before they are used as IS or SS for targeted quantification.

We were able to assess quantitatively the differential expression of small GTPases in the frontal cortex regions of post-mortem brain tissue samples acquired from patients with different stages of AD. Although the current method is not amenable for absolute quantitation, it can be modified to enable absolute quantification by utilizing high-purity SIS peptides.

In conclusion, we developed an MRM-based targeted quantitative proteomic assay for monitoring 389 tryptic peptides (>1600 transitions) with a 70 min linear LC gradient. We also described the use of crude SIL peptides as internal standards or surrogate standards for targeted measurements of small GTPases. The method obviates the needs of metabolic labeling and is directly applicable to high-throughput quantification of small GTPase proteome in tissue samples. It can be envisaged that the method can be generally applicable to the quantitative analysis of small GTPase proteins in other tissue and cellular samples. Our results also led to the discovery of the altered expressions of several synaptic GTPase proteins, including RAB3A/C, RAB4A/B, and RAB27B in higher AD stages. As a proof-of concept case study, the results from the established targeted quantitative proteomic workflow suggested potential roles of synaptic small GTPases in AD progression. Nevertheless, we recognized that a limited number of tissue samples were employed in the present study. This limitation, along with heterogeneity of AD patients, requires expansion of the study to a larger number of patients to further substantiate the findings made from the present work.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 ES025121-04S1 and P50 AG005136), and M.H. was supported by an NRSA T32 Institutional Training Grant (T32 ES018827).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.anal-chem.9b02485.

Detailed experimental procedures and figures showing analytical performance of the LC–MRM method (PDF)

Processed quantification data (XLSX)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Blennow K; de Leon MJ; Zetterberg H Lancet 2006, 368, 387–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s Dementia 2018, 14, 367–429. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Spires-Jones TL; Hyman BT Neuron 2014, 82, 756–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zhang J; Goodlett DR; Montine TJ J. Alzheimer’s Dis 2006, 8, 377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Musunuri S; Wetterhall M; Ingelsson M; Lannfelt L; Artemenko K; Bergquist J; Kultima K; Shevchenko GJ Proteome Res. 2014, 13, 2056–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Seyfried NT; Dammer EB; Swarup V; Nandakumar D; Duong DM; Yin L; Deng Q; Nguyen T; Hales CM; Wingo T; Glass J; Gearing M; Thambisetty M; Troncoso JC; Geschwind DH; Lah JJ; Levey AI Cell Syst 2017, 4, 60–72. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Sathe G; Na CH; Renuse S; Madugundu AK; Albert M; Moghekar A; Pandey A Clin. Proteomics 2018, 15, e1800105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Lleo A; Nunez-Llaves R; Alcolea D; Chiva C; Balateu-Panos D; Colom-Cadena M; Gomez-Giro G; Munoz L; Querol-Vilaseca M; Pegueroles J; Rami L; Llado A; Molinuevo JL; Tainta M; Clarimon J; Spires-Jones T; Blesa R; Fortea J; Martinez-Lage P; Sanchez-Valle R; Sabido E; Bayes A; Belbin O Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2019, 18, 546–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Begcevic I; Kosanam H; Martinez-Morillo E; Dimitromanolakis A; Diamandis P; Kuzmanov U; Hazrati LN; Diamandis EP Clin. Proteomics 2013, 10, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Hondius DC; van Nierop P; Li KW; Hoozemans JJ; van der Schors RC; van Haastert ES; van der Vies SM; Rozemuller AJ; Smit AB Alzheimer’s Dementia 2016, 12, 654–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Andreev VP; Petyuk VA; Brewer HM; Karpievitch YV; Xie F; Clarke J; Camp D; Smith RD; Lieberman AP; Albin RL; Nawaz Z; El Hokayem J; Myers AJ J. Proteome Res 2012, 11, 3053–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zhang Q; Ma C; Gearing M; Wang PG; Chin LS; Li L Acta Neuropathologica Communications 2018, 6, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hales CM; Dammer EB; Deng Q; Duong DM; Gearing M; Troncoso JC; Thambisetty M; Lah JJ; Shulman JM; Levey AI; Seyfried NT Proteomics 2016, 16, 3042–3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ping L; Duong DM; Yin L; Gearing M; Lah JJ; Levey AI; Seyfried NT Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).McKetney J; Runde RM; Hebert AS; Salamat S; Roy S; Coon JJ J. Proteome Res 2019, 18, 1380–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Shi TJ; Song EW; Nie S; Rodland KD; Liu T; Qian WJ; Smith RD Proteomics 2016, 16, 2160–2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Prieto-Dominguez N; Parnell C; Teng Y Cells 2019, 8, 255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Govek EE; Hatten ME; Van Aelst L Dev. Neurobiol 2011, 71, 528–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Li G Curr. Drug Targets 2011, 12, 1188–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Kiral FR; Kohrs FE; Jin EJ; Hiesinger PR Curr. Biol 2018, 28, R471–R486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Rodriguez L; Mohamed NV; Desjardins A; Lippe R; Fon EA; Leclerc NJ Neurochem. 2017, 141, 592–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Vaz-Silva J; Gomes P; Jin Q; Zhu M; Zhuravleva V; Quintremil S; Meira T; Silva J; Dioli C; Soares-Cunha C; Daskalakis NP; Sousa N; Sotiropoulos I; Waites CL EMBO J. 2018, 37, e99084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kundra R; Ciryam P; Morimoto RI; Dobson CM; Vendruscolo M Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2017, 114, E5703–E5711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Scheper W; Hoozemans JJ; Hoogenraad CC; Rozemuller AJ; Eikelenboom P; Baas F Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol 2007, 33, 523–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Ginsberg SD; Alldred MJ; Counts SE; Cataldo AM; Neve RL; Jiang Y; Wuu J; Chao MV; Mufson EJ; Nixon RA; Che S Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 68, 885–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ginsberg SD; Mufson EJ; Alldred MJ; Counts SE; Wuu J; Nixon RA; Che SJ Chem. Neuroanat 2011, 42, 102–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Klassen MP; Wu YE; Maeder CI; Nakae I; Cueva JG; Lehrman EK; Tada M; Gengyo-Ando K; Wang GJ; Goodman M; Mitani S; Kontani K; Katada T; Shen K Neuron 2010, 66, 710–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Huang M; Qi TF; Li L; Zhang G; Wang Y Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 5431–5445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Huang M; Wang Y Anal. Chem 2018, 90, 14551–14560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Huang M; Wang Y Anal. Chem 2019, 91, 6233–6241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Zauber H; Kirchner M; Selbach M Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 156–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Sherwood CA; Eastham A; Lee LW; Risler J; Vitek O; Martin DB J. Proteome Res 2009, 8, 4243–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Pino LK; Searle BC; Bollinger JG; Nunn B; MacLean B; MacCoss MJ Mass Spectrom. Rev 2017, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Picotti P; Aebersold R Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 555–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Kawahara R; Bollinger JG; Rivera C; Ribeiro ACP; Brandao TB; Leme AFP; MacCoss MJ Proteomics 2016, 16, 159–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Escher C; Reiter L; MacLean B; Ossola R; Herzog F; Chilton J; MacCoss MJ; Rinner O Proteomics 2012, 12, 1111–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Shi T; Sun X; Gao Y; Fillmore TL; Schepmoes AA; Zhao R; He J; Moore RJ; Kagan J; Rodland KD; Liu T; Liu AY; Smith RD; Tang K; Camp DG 2nd; Qian WJ J. Proteome Res 2013, 12, 3353–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Zhang CC; Li R; Jiang H; Lin S; Rogalski JC; Liu K; Kast JJ Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 967–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Lam MP; Lau E; Scruggs SB; Wang D; Kim TY; Liem DA; Zhang J; Ryan CM; Faull KF; Ping PJ Proteomics 2013, 81, 15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Kim YJ; Sertamo K; Pierrard MA; Mesmin C; Kim SY; Schlesser M; Berchem G; Domon BJ Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 1412–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Guo X; Trudgian DC; Lemoff A; Yadavalli S; Mirzaei H Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2014, 13, 1573–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hoofnagle AN; Whiteaker JR; Carr SA; Kuhn E; Liu T; Massoni SA; Thomas SN; Townsend RR; Zimmerman LJ; Boja E; et al. Clin. Chem 2015, 62, 48–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Zhang H; Liu Q; Zimmerman LJ; Ham AJ; Slebos RJ; Rahman J; Kikuchi T; Massion PP; Carbone DP; Billheimer D; Liebler DC Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2011, 10, 006593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Sudhof TC Annu. Rev. Neurosci 2004, 27, 509–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Rizzoli SO EMBO J. 2014, 33, 788–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Kokotos AC; Peltier J; Davenport EC; Trost M; Cousin MA Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2018, 115, E10177–E10186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Scheff SW; Price DA; Schmitt FA; Mufson EJ Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 1372–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Pavlos NJ; Gronborg M; Riedel D; Chua JJ; Boyken J; Kloepper TH; Urlaub H; Rizzoli SO; Jahn RJ Neurosci. 2010, 30, 13441–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Takai Y; Sasaki T; Matozaki T Physiol. Rev 2001, 81, 153–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Jahn R Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 2004, 1014, 170–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Gerber SA; Rush J; Stemman O; Kirschner MW; Gygi SP Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2003, 100, 6940–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Whiteaker JR; Lin C; Kennedy J; Hou L; Trute M; Sokal I; Yan P; Schoenherr RM; Zhao L; Voytovich UJ; Kelly-Spratt KS; Krasnoselsky A; Gafken PR; Hogan JM; Jones LA; Wang P; Amon L; Chodosh LA; Nelson PS; McIntosh MW; Kemp CJ; Paulovich AG Nat. Biotechnol 2011, 29, 625–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Demory Beckler M; Higginbotham JN; Franklin JL; Ham AJ; Halvey PJ; Imasuen IE; Whitwell C; Li M; Liebler DC; Coffey RJ Mol. Cell. Proteomics 2013, 12, 343–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.