Abstract

Background and Objectives

Assisted living (AL) is a popular residential long-term care option for frail older adults in the United States. Most residents have multiple comorbidities and considerable health care needs, but little is known about their health care arrangements, particularly over time. Our goal is to understand how health care is managed and experienced in AL by residents and their care network members.

Research Design and Methods

This grounded theory analysis focuses on the delivery of health care in AL. Qualitative data were gathered from 28 residents and 114 of their care network members followed over a 2-year period in 4 diverse settings as part of the larger study, “Convoys of Care: Developing Collaborative Care Partnerships in Assisted Living.”

Results

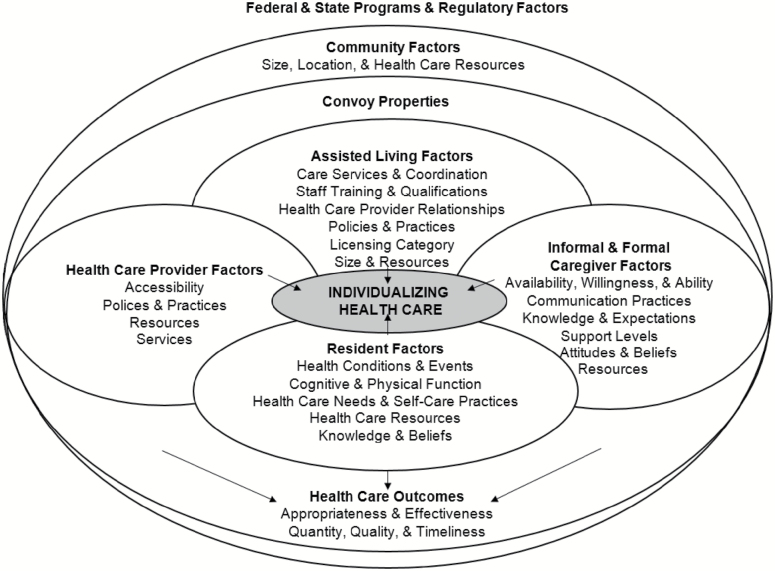

Findings show that health care in AL involves routine, acute, rehabilitative, and end-of-life care, is provided by residents, formal and informal caregivers, and occurs on- and off-site. Our conceptual model derived from grounded theory analysis, “individualizing health care,” reflects the variability found in care arrangements over time and the multiple, multilevel factors we identified related to residents and caregivers (e.g., age, health), care networks (e.g., size, composition), residences (e.g., ownership), and community and regulatory contexts. This variability leads to individualization and a mosaic of health care among AL residents and communities.

Discussion and Implications

Our consideration of health care and emphasis on care networks draw attention to the importance of communication and need for collaboration within care networks as key avenues for improving care for this and other frail populations.

Keywords: Formal care, Health care arrangements, Informal care, Long-term care, Qualitative research

Background and Objectives

Nearly one million elders reside in assisted living (AL), which, as the fastest growing formal long-term care option in the United States, is preferred over more expensive and institutional nursing home environments (Eckert, Carder, Morgan, Frankowski, & Roth, 2009). States vary in what this care option is labeled and what regulations apply, yet most AL communities provide 24-hr oversight, meals, assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs), instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), and medications and health-related and social services (Carder, O’Keeffe, & O’Keeffe, 2015). Conceived as a social, not medical, care model, AL assumes primary responsibility for residents’ personal care needs. The types, levels, and cost of care vary based on service availability and care package selection.

The typical AL resident is aged 85 or older and requires assistance with multiple ADLs and IADLs and medication (Khatutsky et al., 2016) and has significant health care needs (Kistler et al., 2017). Most have at least one chronic condition, with 75% having multiple comorbidities; 33% have heart disease, 28% have depression, 17% are diabetic, and estimates of cognitive impairment range from approximately 40% (Caffrey et al., 2012) to 70% (Zimmerman, Sloan, & Reed, 2014). In 2010, 15% of residents fell and sustained an injury; 35% visited an emergency department; 25% were hospitalized; and 8% had a nursing or rehabilitation facility stay (Khatutsky et al., 2016). Sending residents to the emergency department is a common strategy to manage acute care (Sharpp & Young, 2016), yet these care units are not well equipped to address the complex care needs of frail elders (Hwang & Morrison, 2007).

Despite the potential complexity of residents’ health conditions, most states’ regulations specify that licensed nurses may oversee, but not provide, skilled care and that only licensed personnel or authorized medication aides may administer medications (Carder et al., 2015). Zimmerman and colleagues (2011) found a 42% error rate, excluding timing errors, in their examination of medication preparation and administration in AL; 7% of errors had potential for harm.

A growing number of AL residences have nurses on staff (Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, & Kemp, 2010). Beeber and colleagues (2014) examined licensed nursing staff and health services in AL across 22 states and found a wide range of nursing use with a mix of registered and licensed practical nurses. Service types, from most to least available, included: basic services (e.g., vital signs); technically complex services (e.g., injections); assessments (e.g. cognitive), wound care, and therapies (e.g., pet); testing and specialty services (e.g., x-ray); and gastrostomy and intravenous medication (Beeber et al., 2014). Direct care workers in AL provide the majority of hands-on care and are comprised of certified nursing assistants (34%) and personal care aides (66%); training among the latter group is not standardized and varies nationwide (Kelly, Morgan, Kemp, & Deichert, 2018).

Nationwide, most AL communities offer basic health monitoring, incontinence care, social and recreational services, therapeutic diets, and transportation to medical appointments (Park-Lee et al., 2011). Between 2013 and 2014, whether provided by staff or external providers, half offered social work, mental health, and dental services; the majority offered occupational, physical, and speech therapies and skilled nursing, pharmacy, podiatry, and hospice services (Harris-Kojetin et al., 2016). Availability of therapeutic, social, and nursing services increases with AL community size (Park-Lee et al., 2011); licensed nurses are more common in communities with separate dementia care units (Zimmerman et al., 2014). Typically a designated person serves as “primary point person for health care and health-related activities,” including staffing and staff training, monitoring, paperwork, regulatory compliance, direct care, and coordination of clinical care (Harris-Wallace et al., 2011, p. 98); variation exists in the position and training of this person.

Existing research reveals the growing complexity of health care in AL and offers insight into needs and services. However, little, if any, research focuses on understanding residents’ care arrangements qualitatively and with the full complement of stakeholders. Although AL environments are dynamic, affected by ongoing change, including residents’ functional decline, staff turnover, and policy and regulatory modifications (Perkins, Ball, Whittington, & Hollingsworth, 2012), no known studies have considered resident health care delivery and use in AL over time.

Our research is informed by the Convoys of Care model (Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, 2013), which extends Kahn and Antonucci’s (1980) “Convoy Model of Social Relations.” Consistent with a life course approach, the original model argues that individuals are entrenched in dynamic support networks that surround and accompany them over time. Our modified model applies the convoy metaphor to long-term care, suggesting that individuals are surrounded by dynamic networks (i.e., convoys) of informal and formal caregivers who provide and support care, including but not limited to health care (Kemp et al., 2013). In AL, care convoys could include family, friends, AL staff, and external care workers.

Here, we use data from the grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, 2015) study, “Convoys of Care: Developing Collaborative Care Partnerships in Assisted Living,” which sought to determine how to support informal care and care convoys in AL in ways that promote residents’ ability to age in place with optimal resident and caregiver quality of life. We build on previous analysis which identified variation in convoy structure and function (Kemp et al., 2018). Informal caregiving roles and responsibilities were assumed by a primary person or shared across multiple persons. Care convoys, including formal caregivers, varied based on consensus about care plans and goals, collaboration, and communication, with residents and convoy members “maneuvering” care processes “together, apart, and at odds” (Kemp et al., 2018). Respectively, these three ways of maneuvering align with three convoy types: cohesive, fragmented, and discordant. Although health care was not our initial analytic focus, as data collection and analysis progressed, it emerged as a topic warranting the further examination pursued here.

Using the aforementioned research as a “sensitizing framework” (Strauss & Corbin, 1998, pp. 51–53), we aim to: (a) learn how health care is managed and experienced by AL residents and their convoy members over time; and (b) develop a theory of health care in AL and the factors that shape it.

Research Design and Methods

The broader study and present analysis follow Corbin and Strauss’s (2015) grounded theory approach; data collection, hypothesis generation, and analysis occurred simultaneously and involved constant comparison within the data and the literature. Georgia State University’s Institutional Review Board approved the study. For anonymity, we use pseudonyms for study sites and participants.

Settings and Sample

Between 2013 and 2015, we collected data in four AL communities in Georgia, where, like most states, AL staff may not provide skilled nursing care (Carder et al., 2015). Sites were purposively selected to maximize variation (Patton, 2015) in size, location, ownership, resident characteristics, fee structure, and availability of a dementia care unit. Hillside, located in a rural area, was privately owned and licensed for 11 residents; all were white. Feld House was licensed for 46, foundation run, located in an Atlanta suburb, and catered to the Jewish community. Garden House was privately owned, licensed for 54, most white, and had a small-town location and a dementia care unit. Oakridge Manor, capacity 92, was corporately owned, located in an urban area, and had a dementia care unit; all residents were African American.

Within communities, we initially purposively selected residents to provide information-rich cases (Patton, 2015) varying in personal characteristics, functional status, and health conditions typical of AL residents nationwide and factors influencing care experiences. As data collection progressed, we used theoretical sampling (Corbin & Strauss, 2015) to select residents who offered insights into different personal, health, and care convoy scenarios, such as, residents with low and high care needs and informal support. For instance, early on we learned that residents’ health conditions created differences in convoy structure and function and recruited residents with specific conditions (e.g., heart disease, dementia, Parkinson’s, diabetes) and reliance on different types of formal care (e.g., specialty doctors, physical therapy, hospice). Convoy members also initially were sampled to achieve a range in caregivers and care roles. We subsequently used theoretical sampling to identify optimal data sources to explore and understand care-related concepts (Corbin & Strauss, 2015).

Ultimately, we recruited 28 focal residents: 61% were women; 36% were African American. The majority were unmarried and had a high school education or greater. Table 1 presents residents’ select health characteristics obtained through self-reports, AL records, and convoy member accounts. With conflicting accounts, we deferred to AL records.

Table 1.

Resident Participants’ Select Health Characteristics (N = 28)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline self-rated health | ||

| Excellent | 1 | 4 |

| Good | 10 | 36 |

| Fair | 10 | 36 |

| Poor | 2 | 7 |

| Unable to report | 5 | 18 |

| Baseline assistance | ||

| With three or more ADLs | 16 | 57 |

| With three or more instrumental ADLs | 23 | 82 |

| With medications | 21 | 75 |

| Health conditionsa,b | ||

| High blood pressure | 21 | 75 |

| Dementia diagnosis | 11 | 39 |

| Heart disease | 11 | 39 |

| Depression | 8 | 29 |

| Arthritis | 11 | 39 |

| Osteoporosis | 2 | 7 |

| Diabetes | 4 | 14 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4 | 14 |

| Cancer | 2 | 7 |

| Stroke | 5 | 18 |

| Comorbiditiesb | Min–max | Mean number |

| 2–10 | 5.96 | |

Note: ADL = activities of daily living.

aTen most common conditions among assisted living residents (Caffrey et al., 2012).

bBased on triangulation between self-reports, assisted living records, and information from convoy members; includes all reported conditions.

Shown in Table 2, we enrolled 114 convoy member participants: 5 AL executive directors and 25 staff; 20 external care workers; and 65 informal caregivers. Through informal interviewing and resident and convoy member accounts, however, we learned about a total of 210 informal caregivers.

Table 2.

Care Convoy Member Participants (n = 114)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Formal convoy membersa | ||

| AL workers (n = 29) | ||

| Executive directors | 5 | 17 |

| Registered nurse | 1 | 3 |

| Resident services personnel | 3 | 10 |

| Medication technicians | 4 | 14 |

| Direct care workers | 6 | 21 |

| Activity personnel | 6 | 21 |

| Maintenance and transportation personnel | 2 | 7 |

| External care workers (n = 20) | ||

| Medical doctors | 3 | 15 |

| Registered nurse | 1 | 5 |

| Nurse practitioners | 3 | 15 |

| Speech, occupational, and physical therapists | 7 | 35 |

| Hospice personnel | 5 | 25 |

| Private care aide | 1 | 5 |

| Informal convoy members (n = 65) | ||

| Daughters | 20 | 31 |

| Sons | 10 | 15 |

| Spouses | 2 | 3 |

| Siblings | 6 | 9 |

| Grandchildren | 6 | 9 |

| Other kin (i.e., step-children, in-laws, aunt, uncle, niece) | 13 | 20 |

| Nonkin (friends and volunteers) | 8 | 12 |

| Informal caregiver participants per convoy | Min–max | Mean/median |

| 0–5 | 2.0/2.3 | |

aAll assisted living workers and some external care workers belonged to multiple resident convoys.

Data Collection

Trained gerontology and sociology researchers collected data. Each home’s executive director provided written consent for community access. In Month 1, we conducted in-depth interviews with executive directors and participant observation, including informal conversations with residents, staff, and visitors and involving assent procedures, and began recruiting residents; convoy member recruitment was ongoing. Consent procedures for individuals, including for those without capacity to consent, are detailed elsewhere (Kemp et al., 2017). Briefly, consent was an ongoing process, obtained using written consent and assent procedures. Resident interviews, most conducted in multiple sittings, addressed: personal, residential, and health histories; social relationships; and care needs, arrangements, and experiences. Convoy member interviews targeted residents’ relationships and care needs, arrangements, roles, and experiences. As data collection progressed, we modified interview and observation guides based on ongoing analysis. For instance, we delved deeper into aspects of health promotion related to nutrition and activity programing as their care significance emerged.

Researchers visited all sites at least weekly, totaling 809 visits and 2,225 observation hours, detailed in field notes. After formal interviews, we followed up with residents and AL staff weekly and attempted twice-monthly contact with other convoy members. Follow-ups captured changes in health and care needs and arrangements. Record review yielded information on diagnoses, care plans, treatments, and acute events.

Analysis

We used the qualitative software NVivo 11 to store, manage, and facilitate coding and analysis. Guided by research questions, data, and the literature, we developed codes to capture broad concepts driven by our aims and ongoing data collection and analysis; these codes, refined through ongoing analysis, including researcher discussions and memoing, allowed researchers to organize and manage data for higher level analysis (Kemp, Ball, & Perkins, forthcoming). Coding involved a three-pronged process (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). First, we identified emergent concepts based on questions about health care and issues raised by informants, an analytical process called open coding. Initial codes included, for example, hospice, acute care, and resident involvement. Through axial coding, we related initial to other categories to identify context, intervening conditions, strategies, and outcomes. We created analysis charts and diagrams, noting, for instance, similarities and differences in health care by resident, convoy, setting, and over time. Through axial coding, we identified connections between health care and conditions and strategies that varied by resident, caregiver, and convoy factors and noted variation in residents’ health care arrangements and experiences over time, including receipt of timely and appropriate care. Finally, we used selective coding to refine and integrate our concepts around our core category and map out our final analytical scheme. This stage involved integrating the analysis of individual convoys and sites, which identified variable health trajectories and care regimens across time, the types of factors influencing them, and accompanying outcomes. Our core category, “individualizing health care” characterizes the dynamic and variable processes associated with health care in AL and is represented in our conceptual model (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Individualization and the health care mosaic in assisted living.

Results

Individualization and the Health Care Mosaic

Each resident had a unique evolving mosaic of health care characterized by type, frequency, amount, timing, and location of care, care provider, and outcomes. Lack of uniformity in health care delivery within and across communities, paired with convoy member and resident change, meant fluctuating health care arrangements, experiences, and outcomes captured by our core category, a process we label “individualizing health care.” Derived from our analysis and illustrated in Figure 1 and below, we theorize that this individualization process and the numerous multi-level factors that shape it over time result in an ever-changing mosaic of health care for residents and AL communities. We identified four health care domains: routine, acute, rehabilitative, and end-of-life. To varying degrees, residents and care convoy members participated in each domain. In what follows, we explain each domain, including the nature and location of care, participants, and variability.

Routine care

Routine care had two subdomains: wellness care (i.e., promoting and maintaining health) and chronic disease management. A central component of wellness care encompassed activity/engagement programing, which ideally promoted physical, emotional, cognitive, and social well-being. AL staff were responsible for activities, supported by volunteers and residents’ family members, which varied with residents’ needs, interests, and abilities. Although Hillside, the smallest home, did not have dedicated activity staff or calendar, it offered activities similar to other sites that included exercises, music, games, outings, and special events. Feld House’s activity director summarized her programing goals saying, “I hope every resident feels connected to the other residents, feels like they are valued, feels like their brain is still in gear [and] that they physically are still in gear.”

Homes endeavored to provide balanced meals. Feld House’s director explained, “The goals of the meal program are to create something that’s reasonably balanced nutritionally, that offers quality and taste and customer satisfaction,” noting the difficulty of achieving all. At Hillside, for instance, despite heart problems, hypertension, and diabetes, Charles insisted on gravy and biscuits. Oakridge Manor and Garden House instituted “hydration” programs because, according to one resident, “old people don’t drink enough water,” and installed hand sanitizer stations strategically located.

Chronic disease management involved all convoy members—residents, informal caregivers, AL staff, and health care professionals. Ongoing health monitoring was key and, according to Feld House’s Director of Resident Services, an LPN, required a team approach:

It starts from the caregivers and can go all the way up to me; it involves everyone, dietary, housekeeping, even activities, 'cause everyone sees the resident and knows how they are so if there’s any change you know someone will be able to catch it and notify me or one of the other[s].

Direct care workers were pivotal. A primary care physician who visited Feld explained, “They have a really important role, and more than the family they are there 24/7. They know what their base line is.” Residents and informal caregivers also monitored symptoms. Additionally, chronic disease management entailed blood-pressure, weight, and glucose monitoring, usually performed by AL staff, often following physicians’ orders and entailing communication of results.

Medication administration, a complex process involving AL staff, physicians, pharmacists, and sometimes informal caregivers and residents, was integral to managing chronic disease. AL staff who administered medications required special certification and training as outlined in state regulations. Capacity for resident self-administration was assessed regularly and frequently changed. Seven focal residents self-administered medications. Alice’s daughter explained her mother’s trajectory, “I was getting [medication] for her and she was taking it herself. . . .Then when she was getting a little bit more confused, [the owner] wanted her to have the staff do it.” Certain residents controlled PRN medications, sometimes against the rules. Delores noted:

I’m not supposed to—I keep Aleve in my medicine cabinet. If I wake up in the morning and I’m feeling bad and my arthritis is bad, I’ll take one or two. . . . I don’t want to get to the point that I’m dependent on everything [staff] give me because they might not be here at that time when I’m having [pain] and I need it.

Communication was essential to proper medication management, but, with multiple caregivers and health professionals involved, administration errors, including off-time, missed or incorrect doses, happened. One communication failure between weekday and weekend shifts meant a Garden House resident missed a new medication over the weekend. At Oakridge, one resident who self-medicated accidentally overdosed on pain medication, requiring hospitalization.

Physicians and nurse practitioners (NPs) offered on-site primary care across settings. A physician at Oakridge Manor described typical visits:

[I] do a standard interview with everybody and then I’ll do a focus physical exam, always heart, lungs, abdomen, check the blood pressure, my pulse ox machine, so I’ll check their heart rate and oxygen levels. . . .Usually I will handwrite my orders, and give it to the med tech, and they usually fax it off to [the] pharmacy.

For 15 focal residents, all routine care from health professionals occurred in-house (Kemp et al., 2018). Nine had most off-site, including specialty care. Relative to in-house care, this strategy created greater burden for family and staff. Four residents combined on- and off-site care, depending on service availability and their health and functional status and resources, including informal support.

All sites had monthly podiatry services; the majority of residents participated. Garden House, Feld House, and Oakridge Manor arranged on-site flu vaccinations yearly. Routine dental care was available at Oakridge Manor and Feld House. Only Feld House had a psychiatric social worker and clinical psychologist who visited residents, including one with severe depression and anxiety.

Chronic disease management also involved dietary accommodations, related, for example, to salt, sugar, and cholesterol intake and problems with swallowing and chewing, possibly requiring thickened or pureed food and entailing vigilant monitoring and collaboration between residents, informal caregivers, AL staff, and health professionals.

Acute care

Although most health care in AL was routine, acute care, usually related to a severe injury or illness, was common and typically was provided off-site. AL staff were key players in acute care events and often had to make split-second decisions about appropriate actions and even provide care while awaiting emergency personnel. Brenda, a Feld House resident, described her experience:

I was here a week when I had respiratory arrest, which immediately went into cardiac arrest. I was told I was blue. [Resident Services Director] did heroics on me and I suppose a few others. . . . When the emergency came to Feld House they put the tube in me.

Such events could be stressful for all involved. Brenda’s episode happened in a hall, viewable by residents and staff. Although Brenda and her daughter, who was vacationing abroad, “had worked on papers with the lawyer that there would be no such heroics,” emergency personnel “said it was not clear enough to them and they would have to [intubate her].” Almost all focal residents had advance directives in their AL records, but, as illustrated above, in critical situations such documents may lack clarity and communication with the appropriate person may be impractical or impossible.

Most acute events were less dramatic, but emergency vehicles and personnel were commonplace across homes. Within one 12-hr period, three Feld House residents received in-house emergency care. During data collection, 20 of 28 focal residents were hospitalized, 12 multiple times (Kemp et al., 2018). Such events typically shifted care responsibility from AL staff to hospital-based providers, introducing temporary transitions in convoy structure and function. Ideally, discharge involved collaboration between the hospitalist and primary care providers, residents, informal caregivers, and AL staff. An NP explained the discharge of a Feld House resident:

The hospitalist who was following him, called me and we talked about his needs from when he would be returning. I said to her, “If you could just go ahead and write the orders for speech therapy and anything else you think he needs, they can get that started as soon as he gets in, that would be terrific.”

Dr. Patel, who visited Feld House, characterized this scenario as “the way you dream it can be all the time,” implying lack of universality.

Falls across homes were common. Ten focal residents fell during the study, five multiple times. Some falls required treatment in emergency departments and hospitalization. For example, Garden House resident, Fred, broke a bone in his leg, which required hospitalization, surgery, and in-patient rehab.

Wound care, usually performed by a home health nurse, was common and required collaboration. Dr Patel explained, “If there is a new wound or if something is not healing, I try to follow up and if the home health is not enough, I talk to the family to send them to outpatient wound care.”

Mobile x-ray services, which required a physician order, facilitated on-site diagnosis of acute conditions such as pneumonia. Although only utilized at Feld House, focal resident, Estelle, avoided one hospitalization this way. Off-site diagnostic tests could be stressful for residents and caregivers. Ninety-two-year-old Garden House resident Delores fell and spent 12 hours in the emergency department, where “they X-rayed every part” of her body. Delores found the experience “loud and painful,” saying, “They beat me up and pounded me.”

Rehabilitative care

Rehabilitative care included speech, physical, and occupational therapies and typically followed acute events. Four focal residents had in-patient rehabilitation after hospitalization; 20 had rehabilitation on-site, some multiple times (Kemp et al., 2018).

Each site had preferred home health providers, but selection could not always be controlled. A physical therapist explained, “Referrals either come from the hospitalist . . . or the rehab or from the patient’s primary care physician, if someone has not been in the hospital but they are showing those issues where they need therapy.” Only Oakridge Manor had in-house therapy, though other companies also delivered care on-site. Rarely, residents received therapy off-site. Yet, Fred, unhappy with his on-site provider, switched to a community clinic, which he felt was “helping” and just being out made him “happy.”

On-site therapies required additional communication and collaboration among convoy members, including physicians, residents, care staff, and families. A physical therapist with clients at Feld House explained:

I always communicate with staff because I need them to be informed as to what I’m doing for success. . . . Honestly, the way therapy is, especially with older folks and in an AL facility, if you don’t have somebody that is going to carry through with the recommendations and the plan, those six weeks, or four weeks, or even eight weeks of therapy is kind of for naught.

Across settings, however, collaboration was not always possible.

End-of-life care

We consider end-of-life care as care for residents diagnosed as dying and on hospice care. Hospice was used in all settings, most notably Hillside, where a hospice certified nursing assistant worked on-site 30 hr per week and at one time six of eight residents, including all focal residents, received hospice (Kemp et al., 2018). She suggested that hospice keeps residents “comfortable” and means, “The family don’t have to worry about takin’ ‘em to the doctors or making sure this appointment’s made or making sure they get that medicine. Hospice makes sure all that’s brought here to us.” A hospice director identified the benefits of providing “24/7” support noting, “instead of sending [residents] out to the hospital, they call the on-call hospice nurse,” who helps resolve any medical issues.

All executive directors and health professionals viewed hospice positively, especially because of pain management and reduced strain on staff, residents, and families. Federal regulations require a physician’s order for hospice care, but care directors commonly discussed hospice with residents and families. Five focal residents, three who died, received hospice care during the study, facilitating aging in place with quality care.

As with other care domains, optimum hospice care involved collaboration among care partners: medical professionals, care aides, family members, and, when possible, the resident. Oakridge Manor’s executive director identified “coordination between making sure people say and do what they say they’re going to do as a provider” as a challenge. However, across homes, the perceived benefits outweighed the challenges, including “extra clinical assistance,” “affirmation [for families] of multiple people trying to take care of your loved one,” and “help” having “a better passing.” Most residents and family members hoped residents could die in place in AL.

Illustrative Cases

The two cases below illustrate the individualization of residents’ health care in AL. They show the spectrum of arrangements and experiences, the factors influencing health care, and the outcomes for residents and convoy members.

Jack

Eighty-eight-year-old Jack from Garden House had congestive heart failure, hypertension, an enlarged prostate, chronic back and joint pain, double vision, and borderline diabetes and was a fall risk. He described “good days and bad days” noting how he feels “depends on the overall balance. Individual problems kick up from time-to-time.” A veteran, he received most health care, including from a geriatrician, cardiologist, dermatologist, and ophthalmologist, at the VA hospital, 20 miles away. He had four hospitalizations for heart complications and internal bleeding, afterwards receiving home health nursing care and physical therapy. For minor acute care, he saw a NP, who checked in monthly but, with over 300 patients across 20 AL communities, was not always accessible.

Jack weighed himself daily to assess the appropriate diuretic dosage, in consultation with the med tech, monitored his blood pressure and glucose levels, coordinated his dietary needs with the kitchen, and exercised. His cohesive convoy was led by his local daughter, Anne, his “quarterback” and “center of communication.” A staff member elaborated: “Anne’s been like a medical reporter. She really keeps up with everything and really advocates for him . . . She’s great, and her husband, too.” Anne said of her father’s care:

It’s been great. [The owner] actually arranges for herself or somebody at Garden House to drive him to the VA for appointments. For the most part, he can navigate it. If he’s going to cardiology, I usually will go meet him and attend the appointment with him. Then either my husband and I, or sometimes my daughters, will pick him up. . . . Then in terms of medication, all of that, that’s all online now, which is great. All his medication gets refilled directly, and there are a couple things I have to go online and refill for him that way. . . . Then of course, I’ve engaged with the pharmacy that repackages all the medication.

Garden House’s care coordinator said, “I think Jack’s support from his daughter is admirable. . . .She’s always in the know. She has an amazing relationship with her father, and they talk all the time.” His convoy supported his independence and ability to remain at Garden House despite considerable physical decline. He rated his care convoy as “good” and “great” except Anne, who was “excellent.”

Estelle

Ninety-five-year-old Estelle moved to Feld House from a rehab facility following a stroke. Initially on hospice, she improved and according to Dr Patel, her primary care physician, “came back” to be “very active.” She had congestive heart failure, hypertension, osteoarthritis with chronic knee pain, bladder incontinence, depression, and problems swallowing, which caused bouts of aspiration pneumonia, was hearing impaired and somewhat overweight, and used a wheelchair. Cognitively alert, with a “strong personality,” she managed and monitored her care assertively, but needed help with all ADLs, IADLs, and medications.

Estelle had “a lot of ups and downs in her condition,” including seven falls and three hospitalizations and received on-site physical and speech therapies and skilled nursing, podiatry and mobile x-ray services. Dr Patel visited monthly, was responsive during acute health episodes, once avoiding hospitalization for pneumonia with timely intervention, and communicated with AL staff, home health workers, and Estelle and her three children. Estelle’s children, who all had full-time jobs, shared care responsibilities in a fragmented convoy with little communication except during crises and which, in Estelle’s view, supported her acute needs better than routine problems.

Estelle described receiving “very good care” from AL staff but wished they had more time to assist her with walking. Dr Patel concurred, but overall praised Feld staff, emphasizing the importance of well-trained, adequate, and consistent staff who monitor and communicate changes to “avoid major hospitalization [and], major decline in mental and physical activity.”

Influential Factors

As Figure 1 illustrates, our analysis identified numerous multi-level factors that intersected to shape resident health care. At the societal level, Medicare reimbursement enabled on-site health care services. State AL regulations shaped health care possibilities by stipulating AL staff training and roles and specifying residents’ rights to noncompliance regarding medications and dietary and lifestyle choices.

Community factors included the availability and quality of external health care resources. AL residence factors included size, ownership, fees, location, including accessibility to health care, staffing levels and training, communication practices, and overall care strategies were influential. Garden House’s executive director noted, “We’d like to think that this is their home and whatever they could get in their home they can get here . . . whether it be hospice or physical therapy or, you know, things of that nature.” Each site had a staff member who coordinated care and communicated with residents and convoy members. Oakridge Manor’s care director described her role: “I manage the care of all the residents [and] the staff that gives the care to all the residents.”

On-site health care delivery afforded additional options. For a fee, the three largest homes provided transportation to off-site care, but, without informal backup and adequate staffing, relying on this strategy could limit residents’ access to essential health care. Across sites, investment in hiring and training care and activity staff and in activity programing affected care delivery and management.

Principal resident factors included health, functional status, and informal caregiver support. Residents with greater independence and support, such as Jack, saw more physicians, particularly specialists, externally. Conversely, Estelle relied more on AL staff and on-site professionals. Estelle’s experiences demonstrate that the complexity and severity of a health condition also were germane. Other resident factors include: the desire and ability to participate, care attitudes, goals, and compliance, and health literacy. Jack and Estelle engaged in self-care, yet certain residents lacked the interest, ability, or knowledge to do so. These cases reflect patterns across the sample and illustrate variation in influential factors over time.

Formal and informal caregiver factors included availability, caregiving attitudes and beliefs, resources, support levels, and expectations. Jack’s daughter represented a gold standard but informal support was variable and dynamic. Many informal caregivers had health problems and competing obligations, which also changed with time. Formal caregivers varied in their training and ability to effectively respond to and monitor resident health care needs.

Health care provider factors included availability and responsiveness to residents and convoy members. Jack’s NP’s case load limited her accessibility, and, hence, ability to communicate and collaborate regularly, a key factor in care outcomes. Feld’s NP explained:

I really see myself as part of a larger team that is helping to take care of a particular person. So they have family, they have long time friends, they have staff of the assisted living community and then they also have other providers in the greater community . . . it is important to collaborate with them.

Convoy properties (e.g., size, composition, communication) shaped care arrangements, experiences, and outcomes. With daughter Anne acting as the “center of communication,” Jack’s convoy shows that leadership effectiveness, goal commonality, and relationship quality are particularly important to residents’ receipt of timely and appropriate health care.

Discussion and Implications

With an emphasis on understanding health care holistically and over time, the present analysis advances knowledge and has implications for research, policy, and practice. Derived from our analysis, we offer a conceptual model representing our core category, “individualizing health care.” As the model shows, health care services and when, where, how, and by whom they were provided varied by resident and over time.

AL research on health care frequently overlooks resident and informal caregiver contributions. We found informal caregiver contributions to be pivotal in whether and how health care needs were addressed. Particularly important were their roles in accessing care and coordinating services, in the increasing complex AL health care arena. As other studies show (Ball et al., 2005), their support of resident self-care also was key. Consistent with the literature (Kemp et al., 2013), we also found that informal caregivers’ competing demands frequently curtail their involvement, which can impede timely and appropriate health care.

Reflecting trends nationwide (Harris-Wallace et al., 2011), all study sites had a health care point person during day time hours. Though highly effective, care coordinators in this study could not always guarantee proper resident health care, especially without informal support. Questions remain about placing such responsibility on one person within an organization (Harris-Wallace et al., 2011). Further research is needed.

Direct care workers, who usually administer medications and have a role in health monitoring and therapeutic support, are central players in residents’ health care, a fact inadequately reflected in their remuneration, status, and training (Morgan, Dill, & Kalleberg, 2013). These workers typically experience heavy workloads (Ball et al., 2010), which can impede their ability to support health care, as shown with Estelle’s case. Their required training, in general and regarding medications, also varies across states (Carder et al., 2015). Effective medication management is critical. Consistent with Zimmerman and colleagues (2011), we found evidence of medication errors. Medication management requires further research, practice, and policy attention.

The quality and quantity of activity programing was influenced by the resources invested, including staffing levels and training and care philosophy. Activity-related evaluation should be performed routinely to tailor programing to reflect residents’ health promotion needs and interests (Sandhu, Kemp, Ball, Burgess, & Perkins, 2013).

Residents in all homes utilized an array of in-house health care from external care providers. These services identified acute problems and were especially helpful in reducing informal caregiver burden, particularly regarding transporting residents with physical or cognitive impairment. We found that transportation is an important piece of the AL health care mosaic and pivotal to receiving off-site care. In their ethnographic work on African American AL communities, Ball and colleagues (2005, p. 265) describe transportation as “a huge problem,” particularly for small homes with limited family support and resources. Transportation requires research and policy attention.

Hospice was used in all sites. We confirm that hospice facilitates aging in place with quality care and frequently depends on AL administrators’ support of hospice and integration of hospice services into AL care practices (Ball, Kemp, Hollingsworth, & Perkins, 2014). Embraced by most residents, family, and staff, hospice can be an effective way to manage pain. However, in a recent study comparing hospice care in AL and private homes, Dougherty and colleagues (2015) found that AL residents were less likely to die in an in-patient setting or hospital, but enrolled in hospice later and were less likely to receive opiates for pain. Another study addressing end of life in AL (Vandenberg et al., 2018) shows that many residents, including some on hospice, experience uncontrolled pain. Researchers should examine decision-making processes, particularly within convoys, surrounding hospice use and pain management in AL.

Similar to AL nationwide (Khatutsky et al., 2016), our resident sample experienced frequent falls and other acute events. We found, as did Sharpp and Young (2016), emergency departments are commonly used to manage residents’ acute care, especially with no nurse on staff. Our data support Hwang and Morrison’s (2007, p. 1873) assertion regarding “a disconnect between emergency and elder care.” As they note, adequately serving older adults with increasingly complex health conditions requires changes to the physical environment and care practices in emergency rooms.

Our research adopts an in-depth, comprehensive, and prospective longitudinal approach, but has limitations. First, we collected data in a single state; findings do not capture state regulatory variability. Next, our purely qualitative work provides an in-depth account of health care processes, but quantitative methods or mixed-methods approaches have much to contribute. Third, relatively speaking, resident participants had reasonably good informal support and access to resources, which can influence health care in AL (Ball et al., 2005). We currently are collecting data in settings that reflect the full range found nationwide, including homes with limited resources and family involvement. Finally, although we attempted to interview all convoy members and observe as many care encounters as possible, we did not accompany residents to off-site health care settings. Future research might consider AL residents’ health care experiences in the broader community, including in emergency rooms, hospitals, and rehabilitation centers.

Over a decade ago, Kane and Mach (2007) identified health care as an important AL research agenda. The present analysis contributes to this agenda by: (a) examining how health care is managed and experienced by AL residents and their convoy members over time; and (b) offering a theory elucidating the individualization of residents’ health care in AL. We posit that numerous multi-level factors shape the individualization process, resulting in a dynamic mosaic of health care for residents and AL communities. The availability and involvement of formal and informal caregivers and residents and the quality of relationships, communication, consensus, and collaboration were central and influenced the quality and quantity of resident health care, which ultimately affected residents’ ability to age in place with good quality of life. Health care in AL is complex and dynamic, and involves an array of stakeholders—factors that are essential to acknowledge in research and should be taken into account in the development and implementation of meaningful quality improvement strategies.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R01AG044368 to C. L. Kemp).

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all those who gave so generously of their time and participated in the study. We are very grateful to co-investigators, Elisabeth Burgess, Patrick Doyle, and Jennifer Craft Morgan and to Joy Dillard and Carole Hollingsworth for their valuable contributions and dedication to the study. The authors thank Elizabeth Avent, Christina Barmon, Andrea Fitzroy, Victoria Helmly, Russell Spornberger, and Deborah Yoder for assisting with data collection and analysis activities. The authors also thank Victor Marshall and Frank Whittington for ongoing feedback and mentorship.

References

- Ball M. M., Kemp C. L., Hollingsworth C., & Perkins M. M (2014). “This is our last stop”: Negotiating end-of-life transitions in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies, 30, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. M., Perkins M. M., Hollingsworth C., & Kemp C. L (Eds.). (2010). Frontline workers in assisted living. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. M., Perkins M. M., Whittington F. J., Hollingsworth C., King S. V., & Combs B. L (2005). Communities of care: Assisted living for African American elders. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beeber A. S., Zimmerman S., Reed D., Mitchell C. M., Sloane P. D., Harris-Wallace B.,…Schumacher J. G (2014). Licensed nurse staffing and health service availability in residential care and assisted living. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62, 805–811. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey C., Sengupta M., Park-Lee E., Moss A., Rosenoff E., & Harris-Kojetin L (2012). Residents living in residential care facilities: United States, 2010. NCHS Data Brief, 91: 1–8. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db78.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carder P., O’Keeffe J., & O’Keeffe C (2015). Compendium of residential care and assisted living regulation and policy: 2015 edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Retrieved from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/compendium-residential-care-and-assisted-living-regulations-and-policy-2015-edition [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J., & Strauss A (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty M., Harris P. S., Teno J., Corcoran A. M., Douglas C., Nelson J.,…Casarett D. J (2015). Hospice care in assisted living facilities versus at home: Results of a multisite cohort study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63, 1153–1157. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert J. K., Carder P. C., Morgan L. A., Frankowski A. C., & Roth E. G (2009). Inside assisted living: The search for home. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Kojetin L., Sengupta M., Park-Lee E., Valverde R., Caffrey C., Rome V., & Lendon J (2016). Long-term care providers and services users in the United States: Data from the national study of long-term care providers, 2013–2014. Vital & Health Statistics. Series 3. (38): x-xii, 1-105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Wallace B., Schumacher J. G., Perez R., Eckert J. K., Doyle P. J., Beeber A. S., & Zimmerman S (2011). The emerging role of health care supervisors in assisted living. Seniors Housing & Care Journal, 19, 97–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang U., & Morrison R. S (2007). The geriatric emergency department. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55, 1873–1876. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R. L., & Antonucci T. C (1980). Convoys over the life course: A life course approach. In Baltes P. B. & Brim O. (Eds.), Life span development and behavior (pp. 253–286). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kane R. L., & Mach J. R. Jr (2007). Improving health care for assisted living residents. The Gerontologist, 47(Suppl. 1), 100–109. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.Supplement_1.100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C. M., Morgan J. C., Kemp C. L., & Deichert J. A, (2018). A profile of the assisted living direct care workforce in the United States. Journal of Applied Gerontology. doi: 10.1177/0733464818757000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L., Ball M. M., Morgan J. C., Doyle P. J., Burgess E. O., Dillard J.,…Perkins M. M (2017). Exposing the backstage: Critical reflections on a longitudinal qualitative study of residents’ care networks in assisted living. Qualitative Health Research, 25, 1190–1202. doi: 10.1177/1049732316668817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L., Ball M. M., Morgan J. C., Doyle P. J., Burgess E. O., & Perkins M. M (2018). Maneuvering together, apart, and at odds: Residents’ care convoys in assisted living. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73, e13–e23. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L., Ball M. M., & Perkins M. M (2013). Convoys of care: Theorizing intersections of formal and informal care. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp C. L., Ball M. M., & Perkins M. M (forthcoming). Charting the course: Analytic processes used in a study of residents’ care networks in assisted living. In Humble Á. & Radiname E. (Eds.), Going beyond ‘themes emerged’: Real stories of how qualitative analysis happens. Oxon, UK: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Khatutsky G., Ormond C., Wiener J. M., Greene A. M., Johnson R., Jessup E. A.,…Harris-Kojetin L (2016). Residential care communities and their residents in 2010: A national portrait (DHHS Publication No. 2016-1041). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Kistler C. E., Zimmerman S., Ward K. T., Reed D., Golin C., & Lewis C. L (2017). Health of older adults in assisted living and implications for preventive care. The Gerontologist, 57, 949–954. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan J. C., Dill J., & Kalleberg A. L (2013). The quality of healthcare jobs: Can intrinsic rewards compensate for low extrinsic rewards?Work, Employment and Society, 27, 802–822. doi: 10.1177/0950017012474707 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park-Lee E., Caffrey C., Sengupta M., Moss A. J., Rosenoff E., & Harris-Kojetin L. D (2011). Residential care facilities: A key sector in the spectrum of long-term care providers in the United States (NCHS data brief, no 78). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. (2015). Qualitative methods and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins M. M., Ball M. M., Whittington F. J., & Hollingsworth C (2012). Relational autonomy in assisted living: A focus on diverse care settings for older adults. Journal of Aging Studies, 26, 214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu N., Kemp C. L., Ball M. M., Burgess E. O., & Perkins M. M (2013). Coming together and pulling apart: Exploring the influence of functional status on co-resident relationships in assisted living. Journal of Aging Studies, 27, 317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpp T. J., & Young H. M (2016). Experiences of frequent visits to the emergency department by residents with dementia in assisted living. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.), 37, 30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A., & Corbin J (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing Grounded Theory, second edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg A. E., Ball M. M., Kemp C. L., Doyle P. J., Fritz M., Halpin S.,…Perkins M. M (2018). Contours of “here”: Phenomenology of space for assisted living residents approaching end of life. Journal of Aging Studies. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2018.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S., Love K., Sloane P. D., Cohen L. W., Reed D., & Carder P. C; Center for Excellence in Assisted Living-University of North Carolina Collaborative (2011). Medication administration errors in assisted living: Scope, characteristics, and the importance of staff training. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59, 1060–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman S., Sloane P. D., &Reed P. S (2014). Dementia prevalence and care in assisted living. Health Affairs, 33, 658–666. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]