Abstract

Clinical glucocorticoid use, and diseases that produce elevated circulating glucocorticoids, promote drastic changes in body composition and reduction in whole body insulin sensitivity. Because steroid-induced diabetes is the most common form of drug-induced hyperglycemia, we investigated mechanisms underlying the recognized phenotypes associated with glucocorticoid excess. Male C57BL/6J mice were exposed to either 100ug/mL corticosterone (cort) or vehicle in their drinking water. Body composition measurements revealed an increase in fat mass with drastically reduced lean mass during the first week (i.e., seven days) of cort exposure. Relative to the vehicle control group, mice receiving cort had a significant reduction in insulin sensitivity (measured by insulin tolerance test) five days after drug intervention. The increase in insulin resistance significantly correlated with an increase in the number of Ki-67 positive β-cells. Moreover, the ability to switch between fuel sources in liver tissue homogenate substrate oxidation assays revealed reduced metabolic flexibility. Furthermore, metabolomics analyses revealed a decrease in liver glycolytic metabolites, suggesting reduced glucose utilization, a finding consistent with onset of systemic insulin resistance. Physical activity was reduced, while respiratory quotient was increased, in mice receiving corticosterone. The majority of metabolic changes were reversed upon cessation of the drug regimen. Collectively, we conclude that changes in body composition and tissue level substrate metabolism are key components influencing the reductions in whole body insulin sensitivity observed during glucocorticoid administration.

Keywords: body composition, glucocorticoid, insulin resistance, metabolic flexibility, metabolomics

1. Introduction

Glucocorticoids (GCs) are steroid hormones that act via the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), a member of the nuclear hormone receptor family (NR3C1) [1]. The transcriptional changes that occur as a result of GR activation form the basis of many therapeutic interventions. Indeed, a variety of agonists, both of the steroidal and non-steroidal scaffolds, exist to modulate GR activity in injectable, oral, and topical delivery systems with reduction of inflammatory responses as the most common goal [2–4]. As such, these drugs are used to treat a wide variety of diseases including allergies, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and specific cancers [5–7]. In addition, GCs are frequently used to suppress rejection of transplanted tissues [8]. However, a variety of metabolic side effects must be balanced in clinical treatment and in some cases preclude GC use in diseases with inflammatory causes.

One of the main side effects associated with chronic GC use is the development of steroid-induced diabetes [9–11]. Because GCs induce insulin resistance, it is likely that the reduced insulin action is a key factor leading up to the eventual onset of hyperglycemia [12, 13]. Whether the insulin resistant state manifests mostly due to lipid overload in tissues, changes in metabolic flexibility, or both is unclear at present. However, this information is critical because the ability to treat the side effects of GCs via specific interventional strategies requires a full understanding of the metabolic events that occur during drug delivery. Indeed, the key variables leading to steroid-induced diabetes are not entirely established, prompting our interest in pre-clinical models that will help to define new approaches to address this important clinical problem. For example, how whole body substrate metabolism is impacted by glucocorticoids as well as changes in tissue level substrate switching (i.e., metabolic flexibility) are important aspects that will help to explain the underlying causes of the side effect profiles that ultimately lead to hyperglycemia and associated adverse outcomes.

Therefore, in this study, we investigated the metabolic consequences associated with chronic corticosterone delivery using male C57BL/6J mice. We found that whole body fat mass increased, and insulin sensitivity decreased, during one week of exposure to corticosterone. As a possible explanation for the drug-induced insulin resistance, we observed changes in hepatic glycolytic and pentose phosphate pathway metabolites. Moreover, hepatic metabolic flexibility was markedly reduced in response to corticosterone. In addition, the proliferation marker Ki-67 was induced in β-cells from mice receiving corticosterone; the increase in Ki-67 staining correlated with the area under the curve for the insulin tolerance test but not with total body mass. Importantly, these phenotypes were completely reversed after removing the drug. Collectively, we conclude that changes in body composition and tissue level substrate metabolism are key components influencing the reductions in whole body insulin sensitivity observed during corticosterone administration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice (stock no. 000664) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine) at 9 weeks of age. Mice were group housed and given a minimum of 7 days to acclimate to the photoperiod (12 hours light/12 hours dark) and temperature conditions (22°C ± 1°C). During the acclimation period, mice were given ad libitum access to water and Lab Diet 5015 (catalog no. 0001328). Mice were randomized into study groups, followed by analysis of fed blood glucose and body mass measurements to ensure that these variables were not significantly different at the onset of the intervention. Corticosterone (Cort; catalog no. 27840; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in ethanol and diluted with water to make a 1% ethanol solution for a final concentration of 100 μg/mL. Animals in the vehicle control group were administered 1% ethanol via the drinking water. Vehicle and cort solutions were changed twice weekly. The drug removal phase (washout) involved switching mice to standard drinking water for the duration of the study. Non-fasting blood glucose measurements were obtained from the tail vein using the Bayer Contour Glucometer (Bayer HealthCare LLC, Mishawaka, IN). Measurements of body mass and composition (fat, lean, and fluid mass) were assessed by NMR using a Bruker Minispec LF110 Time-Domain NMR system. Upon completion of the study, animals were fasted for 4 h, anesthetized by CO2 asphyxiation, and then euthanized by decapitation. Fat depots, skeletal muscle, and liver tissue were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen, and pancreata were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. Trunk blood was harvested, and the serum fraction was collected. For measurements of energy expenditure, respiratory quotient (RQ), activity, sleep, food and liquid intake, a second cohort of mice were monitored for a 3 week period (2 weeks of Veh or Cort followed by a one week washout) using Promethion metabolic cages (Sable Systems). Acclimation using training cages followed by metabolic cage setup has been described [14]. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center and the University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

2.2. Sucrose Preference Testing

Plain cookie dough or cookie dough containing corticosterone was mixed using Betty Crocker Sugar Cookie Mix (74% w/w), unsalted butter (17% w/w) and Egg Beaters (9% w/w). Corticosterone was added to dry cookie mix and initially stirred manually and then blended before adding butter and Egg Beaters. The final concentration of corticosterone in cookie dough was 8 mg of corticosterone per gram of cookie dough. Mice in the corticosterone group were fed 16.6 grams of cookie dough per kg of body weight to achieve the target dose of 13. 3 mg/kg. Mice in the control group were fed 16.6 grams of cookie dough per kg of body weight. A 4-day sucrose preference assessment was used to measure the possible anhedonic effects of corticosterone treatment using a previously described method [15]. Briefly, two 50 ml conical tubes with sippers were initially added to the home cage of each mouse. One bottle contained plain water and one bottle contained a 1% sucrose solution. The initial left/right position of the water and sucrose solution tubes was counterbalanced across mice. On each of the following four days, the tubes were weighed, and positions of the tubes switched. Preference for the sucrose solution was measured as the grams of 1% sucrose solution consumed divided by total grams of fluid consumed (sucrose solution + water). Sucrose preference was assessed twice: once, ending four days prior to the start of treatment with corticosterone (13.3 mg/kg using cookie dough with 8 mg of corticosterone per gram of dough) and once beginning on the third day of corticosterone treatment and concluding on the seventh day of corticosterone treatment.

2.3. Peritoneal Inflammation Model and Flow Cytometry

Thioglycollate- induced peritoneal inflammation was carried out as previously described [16]. Briefly, mice were injected i.p. with 3% Brewer’s thioglycollate the same day they were placed on Cort (100 μg/mL) or vehicle control. Four days after injection with thioglycollate, all mice were euthanized and peritoneal exudate was harvested. The mice remained on the Cort or vehicle regimen the entire period prior to euthanasia. Red blood cells were removed from extracted peritoneal exudate using ammonium chloride-potassium lysis buffer. Our procedures for flow cytometry have been described [17]. Briefly, the single cell suspension was stained for flowcytometric analysis with the following fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies targeting the following cellular subsets: anti-Ly6G (1A8), anti-Ly6C (HK1.4) anti-F4/80 (BM8) anti-CD11c (N418), anti-CD19 (6D5) (all from BioLegend) and anti-CD11b (M1/70) from BD Pharmingen. Data was acquired on BD LSR II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo software, version 10.1.

2.4. Insulin Tolerance Test (ITT) and Substrate Oxidation

For insulin tolerance tests, mice were fasted for 2h and injected intraperitoneally with 1.0 U Humulin R insulin (Lilly, Indianapolis, IN) per kg body weight. Blood from the tail was used to track glucose levels pre- and post-insulin injection.

For Liver substrate oxidation, the assays was conducted using liver homogenates as previously described [18–21]. Briefly, using [1-14C] palmitate (100 μM), both complete (14CO2) and incomplete fatty acid oxidation were assessed ± 1 mM unlabeled pyruvate to test metabolic flexibility. Incomplete fatty acid oxidation is defined as 14C-acid soluble metabolites (ASMs). [U-14C]leucine (100 μM) oxidation was measured as the capture of 14CO2.

2.5. Serum ELISA, Liver TG measurements, and Islet Histology

The following kits were used to measure serum factors: Mouse Insulin ELISA kit (Cat # 10–1247-01) and Glucagon ELISA kit (Cat # 10–1271-01) from Mercodia (Uppsala, Sweden). Liver total acyl glycerol measurements have been described in detail in a previous study [18]. Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded pancreatic tissue was sectioned and stained as described previously [12]. Ki-67 (IHC-00375-T; Bethyl labs) and insulin (ab7842; Abcam) co-localization were imaged via a Hamamatsu NanoZoomer fluorescent slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics, K.K., Japan).

2.6. Metabolomics analyses

Water-soluble metabolites were extracted from 10–20 mg tissue samples with 0.1 M formic acid in 4:4:2 acetonitrile:water:methanol, as previously described [22]. Metabolites were analyzed with a previously established untargeted metabolomics method using ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to high resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC-HRMS) (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA, USA)[23]. The chromatographic separations were performed using a Synergi Hydro RP column (100mm × 2.1mm, 2.6 μm, 100 Å) and an UltiMate 3000 pump (Thermo Fischer). The mass analysis was performed using an Exactive Plus Orbitrap MS (Thermo Fischer). After the full scan analysis an open source metabolomics software package, Metabolomic Analysis and Visualization Engine (MAVEN) [24, 25], was used to identify metabolites using exact mass and retention time. Area under the curve was integrated and used for further statistical analyses. Solvents used were HPLC grade (Fischer Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA).

2.7. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using Prism version 7.0 (GraphPad) with p values given in the figure legends. For experiments comparing two groups, a Student’s t-test was used for analysis. For 3 or more groups, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc testing was used. For repeated measures of two groups, such as cross sectional body composition data, paired t-test analysis was conducted. For substrate oxidation assays to assess metabolic flexibility, two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test for multiple comparisons was used. Unless otherwise indicated, statistical significance was denoted with the following designations: * p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001; **** p ≤ 0.0001.

3. Results

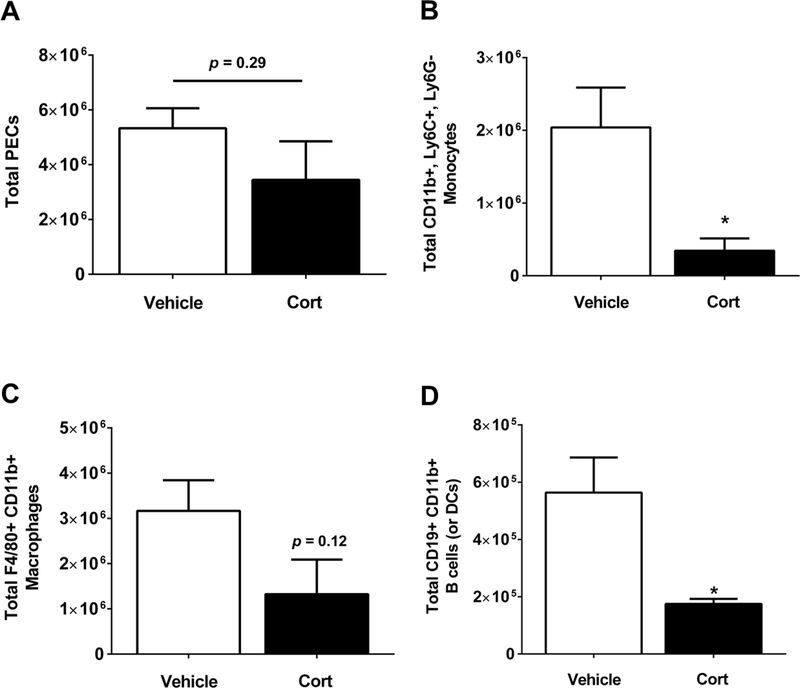

3.1. Corticosterone suppresses thioglycollate-induced recruitment of specific leukocyte populations

Intraperitoneal injection of thioglycollate provokes an inflammatory response defined by recruitment of various leukocytic populations to the peritoneal cavity [16, 26]. Because glucocorticoid treatment is most often used to suppress inflammatory reactions, we characterized the immune response to thioglycollate administration in the presence and absence of Cort. First, we found that total peritoneal exudate cells were not different in mice treated with Cort when compared with the vehicle control (Figure 1A). However, the amount of CD11b+,Ly6C+,Ly6G− cells, which signify inflammatory monocytes, were markedly reduced in Cort-treated mice (Figure 1B). Next, Cd11b+, F4/80+ cells, which represent macrophages, trended lower in the Cort-treated mice (Figure 1C). Finally, Cort-treated mice had fewer Cd11b+, Cd19+ cells, indicating B cells or dendritic cells [27], relative to mice receiving the vehicle control (Figure 1D). Taken together, these data show that Cort does not reduce the total number of cells recruited to the peritoneal cavity in response to thioglycollate, but rather suppressed the recruitment of specific leukocyte populations.

Figure 1. Cort suppresses thioglycollate-induced recruitment of specific leukocyte populations.

Mice were placed on either cort or vehicle control following i.p. injection with 3% thioglycollate. Peritoneal exudate cells were collected 4 days later. (A) Total cell count of the peritoneal infiltrate was determined for both groups. The infiltrate was further analyzed for (B) monocytes, (C) macrophages, and (D) peritoneal B-cells/dendritic cells. Data are means ± S.E. with five mice per group. *, p ≤ 0.05.

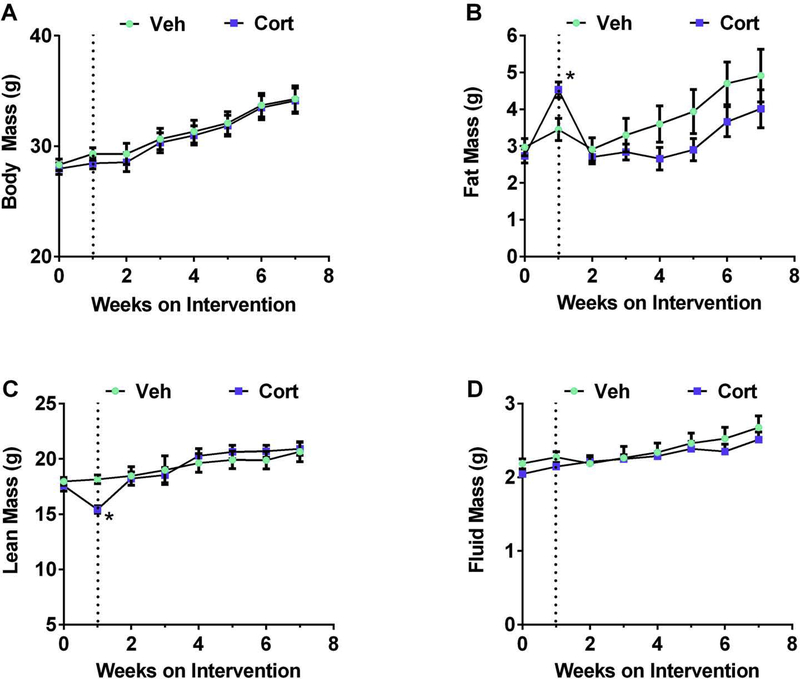

3.2. Early changes in body composition, but not total body mass, in response to corticosterone administration

The anti-inflammatory effects on peritoneal exudate cells induced by thioglycollate occurred within one week (Figure 1). During this time frame, using a separate cohort of mice, we found that total body mass was unchanged throughout Cort administration (Figure 2A). However, fat mass was significantly elevated, a phenotype that was reversed when the drug was removed (Figure 2B). Similarly, lean mass was reduced in mice receiving Cort, but returned to normal when the drug was discontinued (Figure 2C). Fluid mass was not significantly altered during either drug delivery or drug removal (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. Changes in body composition, but not total body mass, appear after one week on Cort.

(A) Body mass, (B) fat mass, (C) lean mass, and (D) fluid mass were measured weekly. Dashed line indicates removal of drug/beginning of washout phase. n=8 per group. *p < 0.05. Data are represented as means ± SEM.

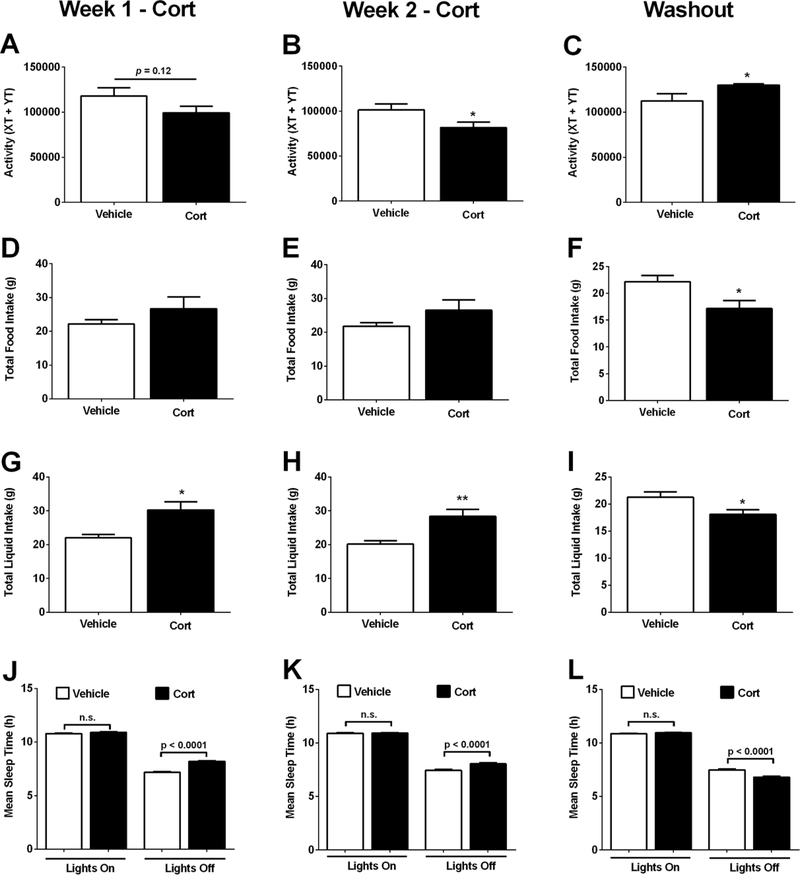

3.3. Corticosterone-mediated alterations in physical activity and sleep time are returned to normal after drug removal

To explain why fat mass accumulates during one week of Cort exposure, we measured activity, food intake, and sleep time as possible explanations. We found that while activity trended lower during the first week on Cort (Figure 3A), by week two it was significantly lower than mice receiving the vehicle control (Figure 3B). After the drug was removed, the phenotype reversed (Figure 3C). Food intake was not different during the two weeks of drug delivery (Figure 3D and 3E), but decreased after removal of the drug (Figure 3F). Liquid intake was greater during the two weeks of Cort administration (Figure 3G and 3H), then was significantly reduced upon discontinuation of the drug (Figure 3I).

Figure 3. Cort-mediated alterations in physical activity and sleep time returned to normal after drug removal.

(A-C) Activity, as measured by total number of X and Y beam breaks, (D-F) weekly food intake (g), (G-I) weekly liquid intake (g), and (J-L) weekly mean sleep time (h), in C57BL/6J mice treated with Vehicle or Cort for 1 (A, D, G J) or 2 (B, E, H, K) weeks, or following a 1 week washout (C, F, I, L). n=8 per group. *p < 0.05. Data are expressed as means ± SEM.

Prior to Cort treatment, differences between the two groups of mice in terms of sucrose preference and total fluid consumed were small and not statistically significant (data not shown). Cort-treated mice consumed more total fluid than vehicle-treated mice (F1,14 = 13.517, p=.002; Supplementary Figure 1A), while differences between the two groups of mice in terms of sucrose preference were non-significant (Supplementary Figure 1B). The largest difference in sucrose preference appeared on the last day of the sucrose preference test with 5 of the 7 Cort-treated mice exhibiting lower sucrose preference than all the vehicle-treated mice (Supplementary Figure 1B and 1C). In addition, reductions in sucrose intake correlated with deposition of fat mass in Cort exposed mice (Supplementary Figure 1D). Related to energy expenditure, an important variable complementary to physical activity is mean sleep time, which was increased during the dark cycle in both the first week (Figure 3J) and second week (Figure 3K). After removal of the Cort, the mice slept less during the dark cycle (Figure 3L), which was consistent with their increased activity after discontinuation of the drug (Figure 3C).

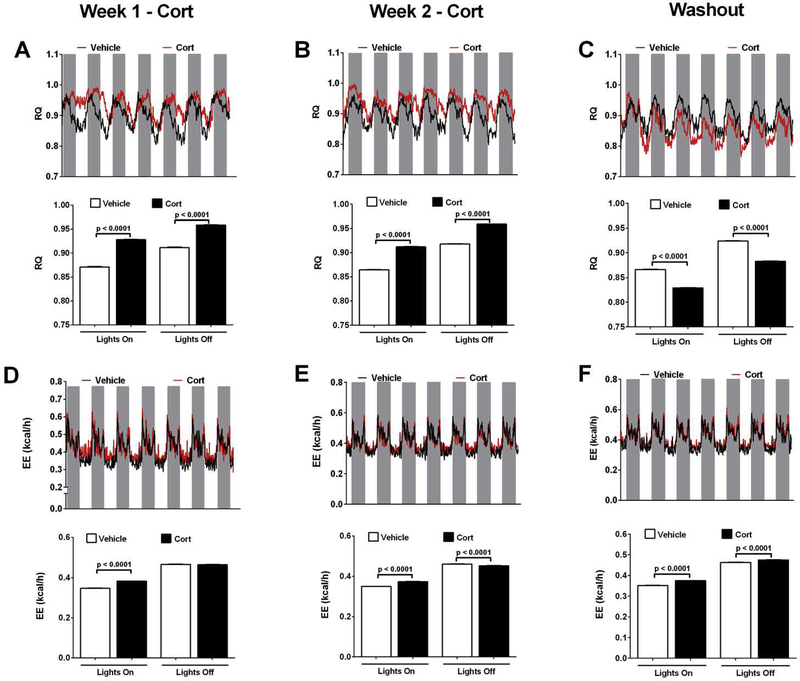

3.4. Corticosterone promotes changes in whole body substrate oxidation which are reversed during the drug washout phase

We observed that exposure to Cort shifted the RQ in both light and dark cycles within the first week of drug delivery (Figure 4A; upper and lower panels). This phenotype persisted into week two of drug exposure (Figure 4B; upper and lower panels). By contrast, one week after washout, the RQ phenotypes were reversed, with reduced RQ in the mice formerly receiving drug in both the light and dark cycles (Figure 4C; upper and lower panels). The changes in energy expenditure were modest, with increases in the light cycle in week one of drug delivery (Figure 4D; upper and lower panels). By week two, the mice receiving Cort had increased energy expenditure in the light but decrease in dark cycles (Figure 4E; upper and lower panels). The increase in energy expenditure persisted even during the drug withdrawal phase (Figure 4F; upper and lower panels).

Figure 4. Cort enhances RQ and Energy Expenditure.

(A-C) Mean respiratory quotient (RQ), (D-F) and mean energy expenditure (EE; kcal/h) in C57BL/6J mice treated with Vehicle or Cort for 1 (A and D; lower panel = quantification of light cycle data shown in top panels; gray bars represent lights off) or 2 (B and E; lower panel = quantification of light cycle data shown in top panels; gray bars represent lights off) weeks, or following a 1 week washout of Cort (C and F; lower panel = quantification of light cycle data shown in top panels; gray bars represent lights off). n=8 per group. Data are shown as means ± SEM.

3.5. Insulin sensitivity is reduced within days after corticosterone exposure and returns to normal after the drug regimen is halted

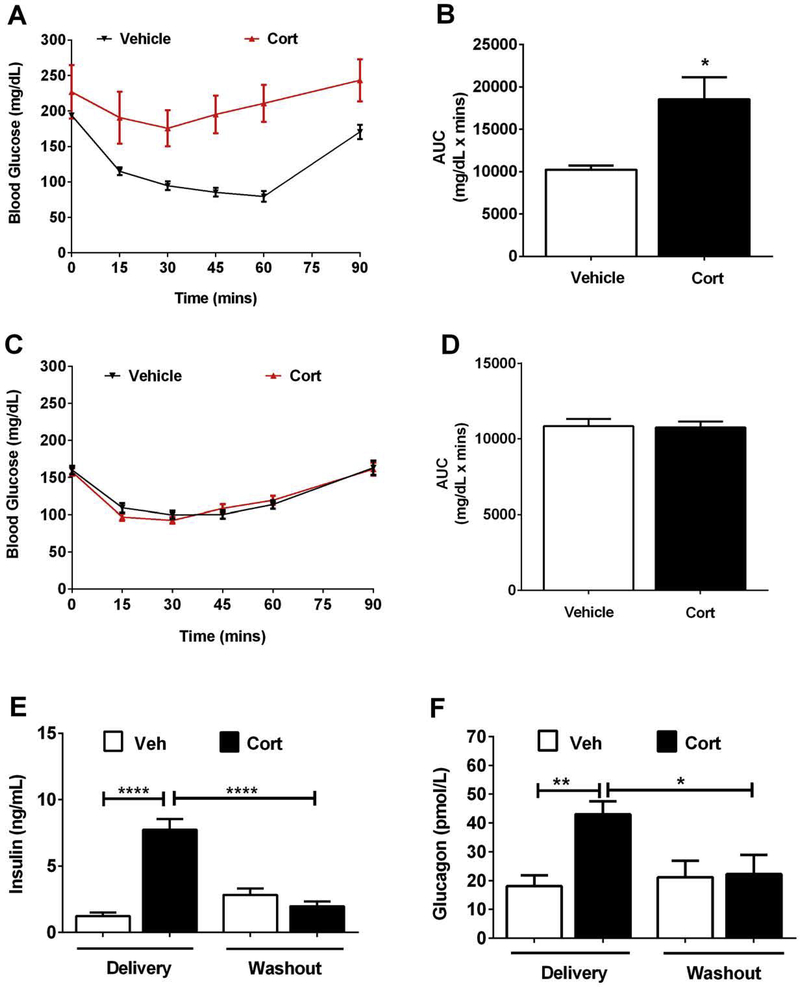

C57BL/6J mice were exposed to Cort or vehicle for five days, followed by insulin tolerance test. The mice receiving Cort were clearly less responsive to the glucose lowering effects of injected insulin (Figure 5A; area under the curve plotted in Figure 5B). After six weeks of washout (i.e., no drug), insulin sensitivity returns to normal (Figure 5C; area under the curve shown in Figure 5D). Using serum insulin as an indirect marker of insulin resistance, we observed a 6.25-fold increase in this circulating hormone compared with mice receiving the vehicle control (Figure 5E; Delivery). However, upon drug removal, the serum insulin returns to normal (Figure 5E; Washout). In addition, circulating glucagon levels follow a similar pattern, with elevations in response to Cort that return to normal when the drug is removed (Figure 5F).

Figure 5. Insulin sensitivity is reduced early after Cort exposure and returns to normal during the drug washout phase.

(A-B) Insulin tolerance test (ITT) after 5 days of Vehicle (Veh) or Cort administration. (C-D) A second ITT on the same cohort of mice following 6 weeks of steroid washout. B and D show the area under the curve calculations for each respective ITT (C = 5d; D = 6w washout). (E) Serum insulin and (F) serum glucagon measured after 7 days of Veh or Cort administration (delivery) and again following a 6 week withdrawal period (washout). n=8 with data represented as means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

3.6. Corticosterone exposure promotes early markers of β-cell proliferation which correlate with insulin resistance, but not with total body mass

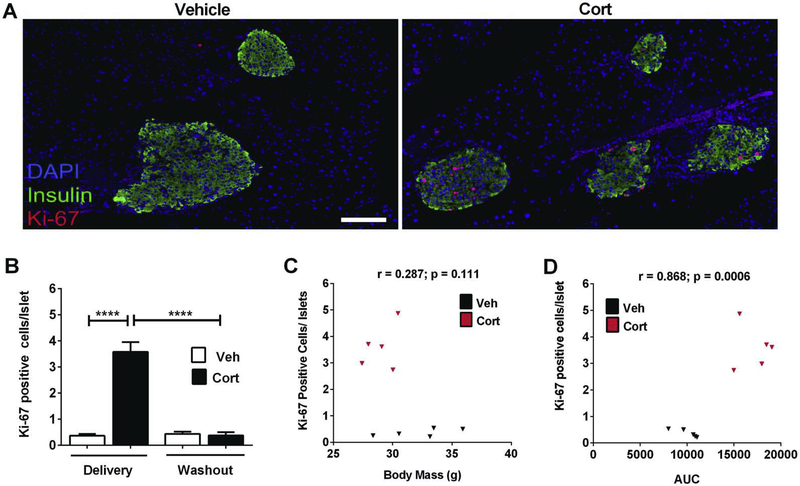

Glucocorticoid treatment leads to insulin resistance within days in both mice (Figure 5) and humans [28]. To determine whether glucocorticoid-induced insulin resistance influences cellular replication, we stained pancreatic sections for Ki-67, an established marker of proliferation [29]. We found that within pancreatic islets, Cort exposed mice had 10-fold more Ki-67 positive cells that co-localized with insulin relative to mice receiving the vehicle control (Figure 6A; quantification in Figure 6B). Upon washout of the drug, the staining for Ki-67 within the islet β-cell population returned to normal levels (Figure 6B and data not shown). We further examined whether Ki-67 positive cells correlated with either total body mass or with insulin resistance. Using Pearson’s r values, we found no significant correlation with total body mass (Figure 6C). By contrast, Ki-67 positive cells highly correlated with area under the curve values for the insulin tolerance test (Figure 6D). Taken together, we interpret these data to indicate that β-cells respond to peripheral insulin resistance with increased insulin output (Figure 5E) and as a signal to proliferation, as evidenced by the enhanced presence of Ki-67 (Figure 6A and 6B).

Figure 6. Cort exposure promotes markers of β-cell proliferation which correlate with insulin resistance, but not with total body mass.

(A) Triple-fluorescence staining of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded pancreatic tissue showing insulin (green), DAPI (blue), and Ki-67 (red) in mice treated with either Vehicle or Cort for 1 week. (B) Quantification of the number of Ki-67+ cells per islet in C57BL/6J mice treated with Vehicle or Cort for 1 week (delivery), or following a 6 week washout of Cort (washout). (C, D) Pearson correlations of Ki-67+ cells per islet quantified from the 1 week delivery period (B) expressed as a function of (C) body mass, and (D) AUC (from ITT data shown in Figure 5). Veh= vehicle; AUC= area under the curve. n=8 per group. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. ****p < 0.0001.

3.7. Corticosterone treatment impairs hepatic metabolic flexibility

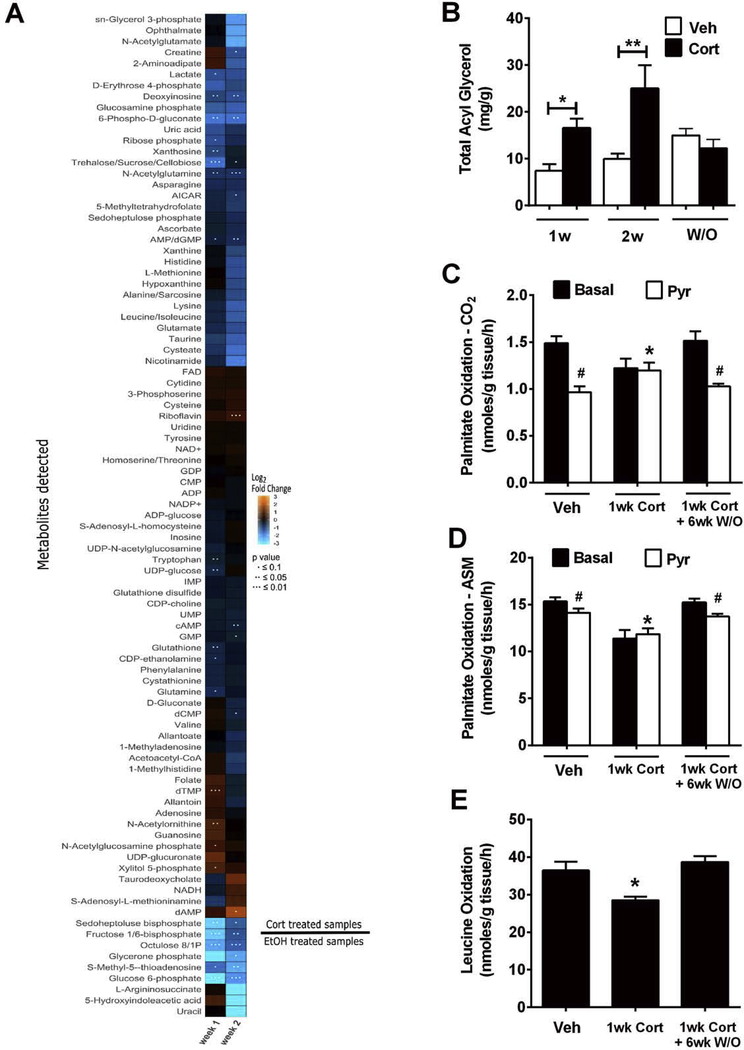

Liver tissue from mice exposed to Cort for one versus two weeks was compared with mice receiving the vehicle control. By principal component analysis, it was clear that data from one week of Cort administration sorted separately from samples obtained after two weeks on the drug. By contrast, the vehicle control data were similar between one and two weeks (Supplementary Figure 2). The heatmap shows that there were clear differences in metabolite profiles between the one week and two week treatment regiments (Figure 7A). A list of the top 10 metabolites showing the greatest increases and decreases by fold change are shown in Table 1. We note that metabolites linked to glucosamine production and glycolysis are among the most robust changes observed. For example N-acetyl glucosamine phosphate is elevated by 1.7 fold while glucosamine phosphate is decreased by 63% (Table 1). In addition, fructose 1, 6-bisphosphate and glucose 6-phosphate are reduced by 84% and 94%, respectively. We interpret these data to indicate that metabolism through glycolysis is markedly inhibited when Cort is present and that carbons are routed to production of hexosamine molecules.

Figure 7. Cort alters liver metabolites and promotes hepatic metabolic inflexibility.

(A) Heatmap illustrating log2 fold changes in relative abundance of metabolites to controls. An orange color indicates a positive fold change and a blue color indicates a negative fold change. P values are indicated with dots. n = 5 mice per group. (B) Total acyl glycerol was measured in the liver of C57BL/6J mice treated with Vehicle or Cort for 1 or 2 weeks, or following a 6 week washout of Cort (W/O). (C-D) Using 100μM [1-14C] palmitate, substrate switching was assessed by measured complete (CO2; C) and incomplete (acid soluble metabolite; ASM; D) fat oxidation ± 1 mM pyruvate as a competing substrate. E. Complete oxidation (CO2) of [U-14C] leucine (100 μM) was used to test effects on branch chain amino acid oxidation. C-E. Assays were run using homogenates from liver from C57BL/6J mice treated with Vehicle or Cort for 1 week (delivery; n = 8 per group), or following a 6 week washout of Cort (washout; W/O; n = 8 per group). *, p < 0.05 vehicle vs. Cort; #, p < 0.05 basal vs. pyruvate.

Table 1.

Metabolites detected from liver tissue of mice after one and two weeks of cort exposure shown by fold change relative to vehicle control. n = 5 mice per group.

| Top 10 Increasing | Top 10 Decreasing | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 1 | Week 2 | ||||||||

| Metabolite | Fold change | p-value | Metabolite | Fold change | p-value | Metabolite | Fold change | p-value | Metabolite | Fold change | p-value |

| UDP-glucuronate | 2.22 | 0.320 | dAMP | 3.69 | 0.092 | Glucosamine phosphate | 0.37 | 0.137 | Nicotinamide | 0.25 | 0.156 |

| Xylitol 5-phosphate | 1.89 | 0.092 | Taurodeoxycholate | 2.35 | 0.231 | D-Erythrose 4-phosphate | 0.35 | 0.223 | Glucose 6-phosphate | 0.23 | 0.013 |

| N-Acetylornithine | 1.87 | 0.017 | S-Adenosyl-L-methioninamine | 1.78 | 0.620 | S-Methyl-5-thioadenosine | 0.31 | 0.084 | sn-Glycerol 3-phosphate | 0.21 | 0.149 |

| Guanosine | 1.84 | 0.107 | NADH | 1.76 | 0.146 | Trehalose/Sucrose/Cell obiose | 0.29 | 0.004 | Ophthalmate | 0.21 | 0.162 |

| 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid | 1.78 | 0.372 | Riboflavin | 1.58 | 0.003 | 6-Phospho-D-gluconate | 0.28 | 0.043 | Glycerone phosphate | 0.20 | 0.082 |

| Folate | 1.74 | 0.354 | Xylitol 5-phosphate | 1.42 | 0.318 | Octulose Phosphate | 0.19 | 0.000 | N-Acetylglutamate | 0.18 | 0.226 |

| N-Acetylglucosamine phosphate | 1.70 | 0.059 | 3-Phosphoserine | 1.40 | 0.655 | Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate | 0.16 | 0.011 | S-Methyl-5-thioadenosine | 0.18 | 0.040 |

| dTMP | 1.66 | 0.014 | Cysteine | 1.37 | 0.491 | Sedoheptoluse bisphosphate | 0.14 | 0.026 | Uracil | 0.09 | 0.118 |

| 2-Aminoadipate | 1.57 | 0.368 | FAD | 1.25 | 0.469 | Glycerone phosphate | 0.12 | 0.106 | 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid | 0.05 | 0.220 |

| Creatine | 1.54 | 0.616 | Cytidine | 1.21 | 0.440 | Glucose 6-phosphate | 0.06 | 6.43E-05 | L-Argininosuccinate | 0.04 | 0.148 |

We also found that triglycerides accumulated in liver tissue of mice that received Cort (Figure 7B). Therefore, we next tested whether substrate switching occurred in liver homogenates exposed to palmitate in the presence or absence of pyruvate. We observed that Cort reduced complete (CO2; Figure 7C) and incomplete (ASM; Figure 7D) palmitate oxidation. Moreover, metabolic flexibility, defined as ability to switch substrates, was lost; however, both phenotypes were completely normalized following a washout period. Likewise, Cort decreased leucine oxidation rates, but this was also normalized after drug removal (Figure 7E). We interpret these data to indicate that hepatic substrate metabolism and metabolic flexibility are altered in the presence of Cort (Figure 7E). Taken together, alterations in hepatic substrate metabolism are highly likely to influence whole body insulin sensitivity, as has been discussed previously [30].

4. Discussion

Glucocorticoids are widely prescribed anti-inflammatory molecules with potent metabolic side effects [31, 32]. Because these steroids are such an important part of clinical therapy, there is a greater need to understand their metabolic actions. In the present study, we put forth several lines of evidence to show that Cort treated mice display early onset of insulin resistance (within days; Figure 5), which is consistent with glucocorticoid administration to humans [33]. Insulin resistance and diabetes are associated with changes in pancreatic islet mass and function [34–37] and with increased hepatic glucose production [38]. Moreover, oral glucocorticoids in humans increase energy expenditure and RQ [39], similar to what we observed in C57BL/6J mice (Figure 4). We further report that islet β-cells from mice exposed to Cort for five days display increased presence of Ki-67 (Figure 6), a widely used marker of cellular proliferation [29]. Our data using Cort exposed mice are consistent with studies using high-fat diets, where proliferation also occurs with days of high-fat feeding in C57BL/6J mice [40, 41]. Along these lines, the degree of Ki-67 positive cells clearly correlated with insulin resistance, but not with total body mass (Figures 6C and 6D). This is consistent with human studies where insulin resistance strongly correlates with increases in β-cell mass [42], but does not correlate well with BMI [43].

Collectively, these observations are congruent with β-cell responsiveness to the changing metabolic needs of the organism, especially during periods of altered peripheral sensitivity to the hormone [37]. In addition, more β-cells are produced as needed via replication, which may be due to mild ER stress that triggers early entry into a proliferative program [44]; this outcome would ultimately provide increased cell mass to account for enhanced insulin requirements. While markers of proliferation were markedly elevated in β-cells during Cort administration, it will be informative to observe time points earlier than five days after GC dosing to determine how rapidly pancreatic β-cells respond to this signal to initiate a proliferative program. In addition, the paradigm of insulin resistance to enhance pancreatic β-cell production and secretion of insulin appears universal, as it occurs in response to high-fat diet, GCs, and many other stimuli (reviewed in ref. [37]). This is important because hyperinsulinemia itself is a risk factor for metabolic disease, including cardiovascular events [45], and appears to occur in conjunction with β-cell replication. Thus, it is possible that the elevated insulin levels, while attempting to compensate for peripheral insulin resistance, also exacerbate existing clinical conditions.

The data in the present study may help inform how GCs induce an adverse metabolic event that eventually contributes to the onset of insulin resistance and diabetes. This is significant because diabetes is a major risk factor that increases mortality in cancer patients [46]. In addition, diabetes due to GC use markedly increased the risk of death in patients with metastatic spinal cord compression [47]. With high-dose glucocorticoids being used in some cases as an adjunct therapy to radiation [48], it is imperative to understand the metabolic consequences associated with GCs. Along these lines, we have examined changes in hepatic substrate metabolism that could influence whole body insulin sensitivity.

Our metabolomics data is consistent with the liver displaying a more ‘fasting like’ state. Indeed, key metabolites of glycolysis, such as glucose-6-phosphate and fructose-1,6-bisphosphate are drastically decreased (Table 1). We interpret these data to indicate that metabolism through glycolysis is distinctly inhibited when Cort is present, which allows carbons to be routed to production of other molecules, such as hexosamines. It is therefore possible that increased flux through the hexosasmine biosynthetic pathway (HBP) is a contributor to the insulin resistance observed in mice exposed to Cort. Consistent with this idea, enhancing the abundance of glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFA) in the liver of mice promotes insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance as they aged [49]. GFA is the rate-controlling enzyme of the HBP and thus increases hexosamine production. Because N-acetyl glucosamine phosphate is elevated by Cort exposure (Table 1), it is possible that the HBP contributes to the insulin resistance observed during these conditions.

In addition, the liver is predicted to account for ~25% of resting energy expenditure [50], which is a substantial contribution to whole body fuel utilization in the basal state. Cort treatment modestly increased energy expenditure in light cycle, and also significantly increased RQ (Figure 4). An increase in RQ is typically interpreted to mean increased carbohydrate oxidation, which seems to contradict the glucose sparing effects of glucocorticoids. In this regard, metabolomics data suggested glycolysis was decreased in the liver while substrate oxidation results revealed an inability of pyruvate to act as a competing substrate to reduce fatty acid oxidation (Figure 7). Together, these data strongly suggest Cort reduces glucose utilization in liver.

While it is possible that increased glucose levels typically observed with a glucocorticoid regimen can induce a mass action affect which necessitates increased whole body glucose oxidation, it is also important to note that states of heightened de novo lipogenesis (DNL) will also increase RQ [51, 52]. Glucocorticoids are capable of increasing DNL [53], so we predict that the increased RQ in the present study is likely to at least partially be explained by increased DNL. Furthermore, a combination of increased DNL and decreased hepatic fatty acid oxidative capacity, as observed in Figure 7C and 7D, would contribute strongly to increased intrahepatic lipid accumulation (Figure 7B) and facilitate excess adiposity (Figure 2B), which are all phenotypes observed during Cort administration. Future isotopic tracer studies that track the metabolic fate of glucose would help clarify this matter.

In summary, a comparison between high-fat feeding and Cort administration reveals that insulin resistance [12, 54], increased β-cell proliferation (see Figure 6A, Figure 6B, and ref. [40, 41]), enhanced β-cell mass [12, 41, 55], elevated insulin in circulation (see Figure 5E and refs. [12, 55, 56]), increased fat mass (see Figure 2B and refs. [12, 56]), and reduced physical activity (see Figure 3B and ref. [57]) are all shared outcomes between these two rodent models. In addition, the mouse as a pre-clinical model of glucocorticoid-induced metabolic perturbations captures several important features of human disease and thus provides a model of insulin resistance distinct from the high-fat fed paradigm in which to investigate key features of metabolic dysregulation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Corticosterone administration alters body composition

Corticosterone modifies hepatic metabolic flexibility

Energy expenditure and sleep time change with corticosterone exposure

Metabolic alterations induced by corticosterone are reversed upon drug withdrawal

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by NIH grant R21 AI138136 (J.J.C.). This study also used facilities supported by the NORC (P30 DK072476) and COBRE (P30 GM118430) Center grants and equipment purchased with funds from a shared instrumentation grant (NIH S10 OD023703). The authors thank Hayley Hall (LSU) and Sara Howard (UTK) for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Granner DK, Wang JC, Yamamoto KR, Regulatory Actions of Glucocorticoid Hormones: From Organisms to Mechanisms, Adv Exp Med Biol, 872 (2015) 3–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ratman D, Vanden Berghe W, Dejager L, Libert C, Tavernier J, Beck IM, De Bosscher K, How glucocorticoid receptors modulate the activity of other transcription factors: a scope beyond tethering, Mol Cell Endocrinol, 380 (2013) 41–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kadmiel M, Cidlowski JA, Glucocorticoid receptor signaling in health and disease, Trends Pharmacol Sci, 34 (2013) 518–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Rhen T, Cidlowski JA, Antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids--new mechanisms for old drugs, N Engl J Med, 353 (2005) 1711–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lin KT, Wang LH, New dimension of glucocorticoids in cancer treatment, Steroids, 111 (2016) 84–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].De Bosscher K, Haegeman G, Elewaut D, Targeting inflammation using selective glucocorticoid receptor modulators, Curr Opin Pharmacol, 10 (2010) 497–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Freishtat RJ, Nagaraju K, Jusko W, Hoffman EP, Glucocorticoid efficacy in asthma: is improved tissue remodeling upstream of anti-inflammation, J Investig Med, 58 (2010) 19–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hwang JL, Weiss RE, Steroid-induced diabetes: a clinical and molecular approach to understanding and treatment, Diabetes Metab Res Rev, 30 (2014) 96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Dirlewanger M, Schneiter PH, Paquot N, Jequier E, Rey V, Tappy L, Effects of glucocorticoids on hepatic sensitivity to insulin and glucagon in man, Clin Nutr, 19 (2000) 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Suh S, Park MK, Glucocorticoid-Induced Diabetes Mellitus: An Important but Overlooked Problem, Endocrinol Metab (Seoul), 32 (2017) 180–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Zhou PZ, Zhu YM, Zou GH, Sun YX, Xiu XL, Huang X, Zhang QH, Relationship Between Glucocorticoids and Insulin Resistance in Healthy Individuals, Med Sci Monit, 22 (2016) 1887–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Burke SJ, Batdorf HM, Eder AE, Karlstad MD, Burk DH, Noland RC, Floyd ZE, Collier JJ, Oral Corticosterone Administration Reduces Insulitis but Promotes Insulin Resistance and Hyperglycemia in Male Nonobese Diabetic Mice, Am J Pathol, 187 (2017) 614–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Beard JC, Halter JB, Best JD, Pfeifer MA, Porte D Jr., Dexamethasone-induced insulin resistance enhances B cell responsiveness to glucose level in normal men, Am J Physiol, 247 (1984) E592–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Burke SJ, Batdorf HM, Martin TM, Burk DH, Noland RC, Cooley CR, Karlstad MD, Johnson WD, Collier JJ, Liquid Sucrose Consumption Promotes Obesity and Impairs Glucose Tolerance Without Altering Circulating Insulin Levels, Obesity (Silver Spring), 26 (2018) 1188–1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Anderson EM, Gomez D, Caccamise A, McPhail D, Hearing M, Chronic unpredictable stress promotes cell-specific plasticity in prefrontal cortex D1 and D2 pyramidal neurons, Neurobiol Stress, 10 (2019) 100152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Baron EJ, Proctor RA, Elicitation of peritoneal polymorphonuclear neutrophils from mice, J Immunol Methods, 49 (1982) 305–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Burke SJ, Lu D, Sparer TE, Karlstad MD, Collier JJ, Transcription of the gene encoding TNF-alpha is increased by IL-1beta in rat and human islets and beta-cell lines, Mol Immunol, 62 (2014) 54–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Burke SJ, Batdorf HM, Burk DH, Noland RC, Eder AE, Boulos MS, Karlstad MD, Collier JJ, db/db Mice Exhibit Features of Human Type 2 Diabetes That Are Not Present in Weight-Matched C57BL/6J Mice Fed a Western Diet, Journal of diabetes research, 2017 (2017) 8503754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wicks SE, Vandanmagsar B, Haynie KR, Fuller SE, Warfel JD, Stephens JM, Wang M, Han X, Zhang J, Noland RC, Mynatt RL, Impaired mitochondrial fat oxidation induces adaptive remodeling of muscle metabolism, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Noland RC, Koves TR, Seiler SE, Lum H, Lust RM, Ilkayeva O, Stevens RD, Hegardt FG, Muoio DM, Carnitine insufficiency caused by aging and overnutrition compromises mitochondrial performance and metabolic control, J Biol Chem, 284 (2009) 22840–22852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Koves TR, Ussher JR, Noland RC, Slentz D, Mosedale M, Ilkayeva O, Bain J, Stevens R, Dyck JR, Newgard CB, Lopaschuk GD, Muoio DM, Mitochondrial overload and incomplete fatty acid oxidation contribute to skeletal muscle insulin resistance, Cell Metab, 7 (2008) 45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tague ED, Bourdon AK, MacDonald A, Lookadoo MS, Kim ED, White WM, Terry PD, Campagna SR, Voy BH, Whelan J, Metabolomics Approach in the Study of the Well-Defined Polyherbal Preparation Zyflamend, J Med Food, 21 (2018) 306–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Lu W, Clasquin MF, Melamud E, Amador-Noguez D, Caudy AA, Rabinowitz JD, Metabolomic analysis via reversed-phase ion-pairing liquid chromatography coupled to a stand alone orbitrap mass spectrometer, Anal Chem, 82 (2010) 3212–3221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Melamud E, Vastag L, Rabinowitz JD, Metabolomic analysis and visualization engine for LC-MS data, Anal Chem, 82 (2010) 9818–9826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Clasquin MF, Melamud E, Rabinowitz JD, LC-MS data processing with MAVEN: a metabolomic analysis and visualization engine, Curr Protoc Bioinformatics, Chapter 14 (2012) Unit14 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Leijh PC, van Zwet TL, ter Kuile MN, van Furth R, Effect of thioglycolate on phagocytic and microbicidal activities of peritoneal macrophages, Infect Immun, 46 (1984) 448–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bjorck P, Kincade PW, CD19+ pro-B cells can give rise to dendritic cells in vitro, J Immunol, 161 (1998) 5795–5799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kauh EA, Mixson LA, Shankar S, McCarthy J, Maridakis V, Morrow L, Heinemann L, Ruddy MK, Herman GA, Kelley DE, Hompesch M, Short-term metabolic effects of prednisone administration in healthy subjects, Diabetes Obes Metab, 13 (2011) 1001–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Scholzen T, Gerdes J, The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown, J Cell Physiol, 182 (2000) 311–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Collier JJ, Scott DK, Sweet changes: glucose homeostasis can be altered by manipulating genes controlling hepatic glucose metabolism, Mol Endocrinol, 18 (2004) 1051–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Schacke H, Docke WD, Asadullah K, Mechanisms involved in the side effects of glucocorticoids, Pharmacol Ther, 96 (2002) 23–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].De Bosscher K, Haegeman G, Minireview: latest perspectives on antiinflammatory actions of glucocorticoids, Mol Endocrinol, 23 (2009) 281–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Willi SM, Kennedy A, Wallace P, Ganaway E, Rogers NL, Garvey WT, Troglitazone antagonizes metabolic effects of glucocorticoids in humans: effects on glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, suppression of free fatty acids, and leptin, Diabetes, 51 (2002) 2895–2902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Marchetti P, Bugliani M, Boggi U, Masini M, Marselli L, The pancreatic beta cells in human type 2 diabetes, Adv Exp Med Biol, 771 (2012) 288–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lindstrom P, beta-cell function in obese-hyperglycemic mice [ob/ob Mice], Adv Exp Med Biol, 654 (2010) 463–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].In’t Veld P, Marichal M, Microscopic anatomy of the human islet of Langerhans, Adv Exp Med Biol, 654 (2010) 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Burke SJ, Karlstad MD, Collier JJ, Pancreatic Islet Responses to Metabolic Trauma, Shock, 46 (2016) 230–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Laskewitz AJ, van Dijk TH, Bloks VW, Reijngoud DJ, van Lierop MJ, Dokter WH, Kuipers F, Groen AK, Grefhorst A, Chronic prednisolone treatment reduces hepatic insulin sensitivity while perturbing the fed-to-fasting transition in mice, Endocrinology, 151 (2010) 2171–2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chong PK, Jung RT, Scrimgeour CM, Rennie MJ, The effect of pharmacological dosages of glucocorticoids on free living total energy expenditure in man, Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 40 (1994) 577–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Stamateris RE, Sharma RB, Hollern DA, Alonso LC, Adaptive beta-cell proliferation increases early in high-fat feeding in mice, concurrent with metabolic changes, with induction of islet cyclin D2 expression, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 305 (2013) E149–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mosser RE, Maulis MF, Moulle VS, Dunn JC, Carboneau BA, Arasi K, Pappan K, Poitout V, Gannon M, High-fat diet-induced beta-cell proliferation occurs prior to insulin resistance in C57Bl/6J male mice, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 308 (2015) E573–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Mezza T, Muscogiuri G, Sorice GP, Clemente G, Hu J, Pontecorvi A, Holst JJ, Giaccari A, Kulkarni RN, Insulin resistance alters islet morphology in nondiabetic humans, Diabetes, 63 (2014) 994–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dybala MP, Olehnik SK, Fowler JL, Golab K, Millis JM, Golebiewska J, Bachul P, Witkowski P, Hara M, Pancreatic beta cell/islet mass and body mass index, Islets, 11 (2019) 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sharma RB, O’Donnell AC, Stamateris RE, Ha B, McCloskey KM, Reynolds PR, Arvan P, Alonso LC, Insulin demand regulates beta cell number via the unfolded protein response, J Clin Invest, 125 (2015) 3831–3846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Garcia RG, Rincon MY, Arenas WD, Silva SY, Reyes LM, Ruiz SL, Ramirez F, Camacho PA, Luengas C, Saaibi JF, Balestrini S, Morillo C, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Hyperinsulinemia is a predictor of new cardiovascular events in Colombian patients with a first myocardial infarction, Int J Cardiol, 148 (2011) 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Barone BB, Yeh HC, Snyder CF, Peairs KS, Stein KB, Derr RL, Wolff AC, Brancati FL, Long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis, JAMA, 300 (2008) 2754–2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Schultz H, Pedersen-Bjergaard U, Jensen AK, Engelholm SA, Kristensen PL, The influence on survival of glucocorticoid induced diabetes in cancer patients with metastatic spinal cord compression, Clin Transl Radiat Oncol, 11 (2018) 19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Sorensen S, Helweg-Larsen S, Mouridsen H, Hansen HH, Effect of high-dose dexamethasone in carcinomatous metastatic spinal cord compression treated with radiotherapy: a randomised trial, Eur J Cancer, 30A (1994) 22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Veerababu G, Tang J, Hoffman RT, Daniels MC, Hebert LF Jr., Crook ED, Cooksey RC, McClain DA, Overexpression of glutamine: fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase in the liver of transgenic mice results in enhanced glycogen storage, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and impaired glucose tolerance, Diabetes, 49 (2000) 2070–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Wang Z, Heshka S, Gallagher D, Boozer CN, Kotler DP, Heymsfield SB, Resting energy expenditure-fat-free mass relationship: new insights provided by body composition modeling, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 279 (2000) E539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Simonson DC, DeFronzo RA, Indirect calorimetry: methodological and interpretative problems, Am J Physiol, 258 (1990) E399–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Elia M, Livesey G, Theory and validity of indirect calorimetry during net lipid synthesis, Am J Clin Nutr, 47 (1988) 591–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Berdanier CD, Role of glucocorticoids in the regulation of lipogenesis, FASEB J, 3 (1989) 2179–2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Laskewitz AJ, van Dijk TH, Grefhorst A, van Lierop MJ, Schreurs M, Bloks VW, Reijngoud DJ, Dokter WH, Kuipers F, Groen AK, Chronic prednisolone treatment aggravates hyperglycemia in mice fed a high-fat diet but does not worsen dietary fat-induced insulin resistance, Endocrinology, 153 (2012) 3713–3723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Fransson L, Franzen S, Rosengren V, Wolbert P, Sjoholm A, Ortsater H, beta-Cell adaptation in a mouse model of glucocorticoid-induced metabolic syndrome, J Endocrinol, 219 (2013) 231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hoffler U, Hobbie K, Wilson R, Bai R, Rahman A, Malarkey D, Travlos G, Ghanayem BI, Diet-induced obesity is associated with hyperleptinemia, hyperinsulinemia, hepatic steatosis, and glomerulopathy in C57Bl/6J mice, Endocrine, 36 (2009) 311–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Vellers HL, Letsinger AC, Walker NR, Granados JZ, Lightfoot JT, High Fat High Sugar Diet Reduces Voluntary Wheel Running in Mice Independent of Sex Hormone Involvement, Front Physiol, 8 (2017) 628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.