Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this descriptive phenomenological study was to explore the nature of post-traumatic growth (PTG) in Turkish breast cancer survivors in the post-treatment first two years.

Materials and Methods

Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted with 13 breast cancer survivors. Data were collected between August 2015 and January 2016 in the medical oncology outpatient clinic of a university hospital in Turkey.

Results

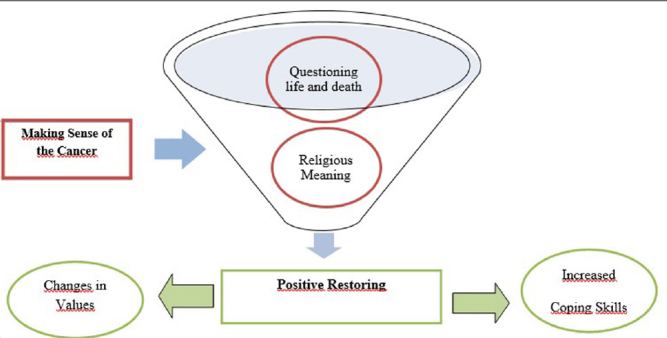

Two main themes were identified. They are as follows: making sense of the cancer (questioning life and death and religious meaning) and positive restoring (changes in values and increased coping skills).

Conclusion

Health care professionals should be aware of these positive changes in the post-treatment period in accordance with aspects of PTG and they should be designed programs directed towards facilitating and enhancing post-traumatic growth in the breast cancer survivors.

Keywords: Breast cancer, survivors, post-traumatic growth, qualitative study

Introduction

The number of breast cancer survivors is increasing with advances in diagnostic techniques and treatment of breast cancer (1, 2). Despite this increase, breast cancer is a traumatic experience including serious biopsychosocial and existential changes (3). Although researchers have traditionally been interested in these negative changes following breast cancer, focusing only on negative effects of traumatic experiences causes failure to understand post-traumatic reactions (4). In fact, traumatic life events like breast cancer can result in positive changes called post-traumatic growth (PTG) (5, 6). Health care professionals knowing the nature of PTG after breast cancer can provide better guidance for breast cancer survivors in recognition of positive aspects of their lives facilitate positive interpretations of their disease experiences and strengthen them in terms of coping with negative effects of the cancer.

Post-traumatic growth is individuals’ experiencing of meaningful positive changes arising from their struggles with major life difficulties. They experience a positive change in self-perception, interpersonal relationships and life philosophy (spiritual and existential changes) (6). The term “growth” means that these individuals have exceeded their prior adjustment abilities, psychological functioning or life awareness (6, 7). Although research in psycho-oncology focuses on negative outcomes of breast cancer, there has been a rise in the number of studies examining PTG in the breast cancer journey. However, there is limited information about post-treatment PTG in breast cancer survivors. Most of the relevant research has focused on predictors, prevalence and domains of PTG (5). In addition, the Post-traumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI) has been extensively used in adult cancer populations including breast cancer (7). PTGI includes five domains: personal strength, new possibilities, relating to others, appreciation for life, and spiritual change (8). Frequently described domains of PTG for breast cancer survivors are increased personal strength, enhanced appreciation of life and deeper relationships with others (9, 10). However, the quantitative methodology may cause difficulty in understanding and gaining a deep insight into life experiences of the survivors about each of five PTG domains and the ways through which growth and related variables mediate positive changes. Qualitative methodology can provide a rich understanding of PTG following breast cancer (11).

Only a few qualitative studies have specifically been directed towards explaining the nature of the PTG in the post-treatment period (12–14). One of these studies focused on positive changes in Japanese breast cancer survivors in different survival phases (post-surgical 1.2 to 26.5 years). The study showed that the survivors had awareness of death and life, strengthened trust in their families and friends, increased appreciation of life, awareness of self, empathy for others, hope for the future, willingness to help others and lifestyle changes (14). Fallah et al. (13) in their study on PTG in Iranian breast cancer survivors revealed the themes closeness to God, making meaning to suffering, and spiritual development, self-confidence, resiliency, improvement in problem solving and positive thinking skills, appreciation of life and thanks to God. In a qualitative study on Indian breast cancer survivors, closer, emphatic and warmer relationships, prioritizing oneself, feeling mentally stronger, positive changes in perspectives toward life, and richer spiritual dimension of life were described (12).

The present study is the first one carried out to describe the phenomenon of PTG in Turkish breast cancer survivors. Socio-cultural factors are environmental factors affecting PTG (15). In Turkish culture, cancer has negative connotations. Breast cancer patients identify cancer with death and suffering and its prognosis with uncertainty (16). One other factor likely to affect PTG can be related to social support. It plays an important role in Turkish culture. Some researchers have also noted that presence of social support can make great contributions to development of PTG (17, 18). The aim of this study was to explore the nature of PTG in Turkish breast cancer survivors. Results of the study are expected to provide guidance in development of effective interventions facilitating PTG and to provide insight into addressing PTG as a source of support for survivors’ early adaptation to the post-treatment.

Materials and Methods

Design

In this study, a descriptive phenomenological approach was used. This approach helps to gain insight into the meaning of PTG in breast cancer survivors’ life/world (19). We used the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) to guide the reporting of this study (20).

Participants

The study was conducted on breast cancer survivors followed in a Medical Oncology outpatient clinic of a university hospital in Turkey. To recruit a diverse sample, variability in age, employment status and clinical parameters was achieved. Inclusion criteria were age of over 18 years, completion of hospital-based treatment lasting minimum six months and maximum two years before the study and not having metastasis. First, patient records were examined in terms of the inclusion criteria and a list of potential participants was created. Each potential participant was contacted on the phone and was explained the aim of the study. Three survivors refused to participate in the study. Those agreeing to participate in the study were scheduled for interviews. The study sample consisted of 13 breast cancer survivors.

Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews by the first author, having knowledge and experience about the qualitative method. Before each interview, informed consent was obtained from the participant. The participants were individually interviewed in a one-to-one and face-to-face basis in a quiet, comfortable room in their home. The interviews were conducted in accordance with a semi-structured interview schedule including open-ended questions (Table 1). It was created by the researchers in light of the literature to help the participants describe their experiences in PTG. Each interview lasted between 30 and 47 min and was audiotape-recorded. The interviews were recorded with the same voice recorder and each participant was interviewed once. They continued until a saturation point at which no new information was obtained. Although data saturation was reached at the eleventh interview, the researcher conducted two more interviews.

Table 1.

Semi-Structured Interview Schedule

| Breast cancer is an experience that affects a woman’s life in many aspects. After this experience, women experience not only negative but also positive changes. Could you please tell me⋯ |

| What positive life changes associated with breast cancer you have had? |

| What these changes are like? |

| In what areas of your life have you experienced these positive changes? |

Data analysis

All the interviews were verbatim transcribed by the first author. Data analysis was made independently by two researchers experienced in qualitative research. In a descriptive phenomenological study, only the data gathered are analyzed and the analysis is made only to describe the phenomenon without interpreting or explaining it and to shed light on the essence of the phenomenon (21). The analysis was inspired by Colaizzi’s descriptive phenomenological data analysis method. It proceeded as follows: Each transcript was read and reread until it could be divided into significant statements. These statements were coded, and a list of codes was created. Similarities and differences between the codes were determined and meanings were formulated from these statements. The formulated meanings were assigned into categories. Each category was named in accordance with its content. Then themes were defined, and the researchers agreed on the themes. The structure of the phenomenon was described. Finally, the participants’ approval about the results of the research was obtained (22).

Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness approaches; credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability were based in the research process (23). Credibility and transferability were achieved by using a semi-structured interview schedule and obtaining expert opinions about questions. The researchers tried to get a deep understanding of information obtained at the interviews. The participants with various backgrounds were included into the study so that differences related to positive life changes could be revealed. The research team consisted of two female researchers and they were trained in qualitative research. The interviews were conducted by the first author who educated and experienced about qualitative studies. To achieve dependability and confirmability, data analysis was made independently by two researchers. The consent of the participants regarding themes was obtained.

This study was approved by the ethical review boards at the Dokuz Eylül University. Only the women volunteering to participate in the study were included. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants before the interviews.

Results

The study sample comprised 13 breast cancer survivors with a mean age of 48.76 years. Of 13 women, five were high school graduates, 11 were married and 10 were unemployed. They had completed their hospital-based treatment of 13.30 months on average, prior to participation in the study (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Survivors (n: 13)

| Participant | Age (Years) | Education | Marital Status | Number of Children | Employment | Stage | Months since post-treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 41 | Primary School | Married | 2 | Not Employed | I | 22 |

| II | 53 | High School | Single | 2 | Not Employed | II | 10 |

| III | 46 | Primary School | Married | 1 | Not Employed | II | 18 |

| IV | 40 | High School | Married | 1 | Not Employed | II | 11 |

| V | 48 | Primary School | Married | 2 | Not Employed | II | 9 |

| VI | 45 | University | Married | 0 | Not Employed | I | 14 |

| VII | 61 | High School | Married | 1 | Not Employed | III | 7 |

| VIII | 50 | University | Married | 1 | Not Employed | II | 17 |

| IX | 52 | University | Married | 1 | Employed | II | 20 |

| X | 70 | University | Married | 1 | Not Employed | III | 16 |

| XI | 39 | High School | Married | 0 | Employed | II | 9 |

| XII | 34 | High School | Single | 0 | Employed | III | 8 |

| XIII | 55 | Primary School | Married | 2 | Not Employed | II | 12 |

The findings showed that the women had a positive restoring process in the post-treatment period and made sense of cancer promoting PTG. Thus, two themes emerged: making sense of cancer and positive restoring (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of themes and sub-themes

Theme 1. Making Sense of Cancer

The women mentioned their interpretations of cancer while explaining their positive experiences. They defined breast cancer as a traumatic experience. They reported to question the meaning of cancer in their lives upon facing breast cancer. This theme involved the subthemes questioning life and death and religious meaning.

Questioning life and death

The women mostly identified breast cancer with death. Diagnosis of cancer forced them to question life and death. They reported that they were aware of the reality of death and that this awareness had a contribution of increasing the value of life. “First, one thinks about life and death. Normally, no one thinks that death is something concrete and may happen to everyone. However, it is real. In view of this reality, one realizes that life is short.” (Participant IX).

Religious meaning

Some women reported that they interpreted cancer based on their religious beliefs. They said their experience with cancer strengthened them and they attributed this to their religious interpretations of cancer. These women assumed that cancer was God’s warning to a person in order to reorganize their life. For these women, God had a purpose in giving this disease, and for them, trying to understand this purpose was associated with growth. “God (Allah) warned me not to get upset about anything and to prioritize my own needs” (Participant II).

Some of the women said that they perceived the disease as a test given by God to check whether they are patient. They believed that, in this process, God was with them, and that they would be rewarded by God if they showed patience (such as healing from cancer). “I thought this disease was a test given by God. I stayed patient and grew stronger” (Participant XI).

Theme 2. Positive Restoring

The post-treatment period was a restoring process. The women reported to have positive life experiences during this restoring process. This theme involved the subthemes changes in values and increased coping skills.

Changes in values

Breast cancer caused the women to question their values. They described changes in the value of life, self-value and relationships after this questioning. The women reported that they recognized the value of life and felt more committed to life after breast cancer. “I used to live without being aware of beauty of life, but now I can say life is beautiful despite all difficulties. It is great to survive. I have found out it while struggling against the disease; I suffered from serious side-effects of chemotherapy” (Participant XII).

With the increased value of life, priorities of the women also changed. Being healthy became the main priority for the women. “Now I feel different from the past. I care about nothing except my health. I have discovered that nothing is more important than health” (Participant IV). Becoming aware of the value of life brought about seizing the day. “I understand how valuable every day is and consider a day as beautiful if it is spent with a loved one. I understand that nothing is important in life; neither money nor status is important” (Participant VIII). The women aware of the value of life noted that they did not postpone anything. “I’ve realized that life is short, and I must enjoy everything. I used to put off realizing my plans, but now I don’t miss anything enjoyable” (Participant IV). The women also reported changes in self-value after breast cancer. They prioritized their own needs: “First, I meet my needs and then needs of others. I try doing things for myself. I used to take account of others’ criticisms, but now they are unimportant for me” (Participant III).

Considered as a traumatic experience, having breast cancer caused changes in values attributed to relationships. The women realized that their families were very precious for them: “I’ve found out that life is not very important, but my family and loved ones are important (Participant XIII).” The women also questioned their relationships with others. “I’ve determined the degree of my relationship with each of my friends. Now I know how close my friends and my relatives are” (Participant XII). After this questioning, the women put an end to some of their relationships, but the value of their other relationships increased. “I became aware of my values such as respect. Now I’ve limited my relationships with friends who do not respect me. I’ve become aware of the value of my friends who gave both financial and social support during diagnosis and treatment of the disease. It appears that the real gain in life is to have real friends” (Participant III).

In addition to awareness of the value of their friends, the women described growth in the value of their relationships with their spouses. Some women mentioned that their bond with their spouses was strengthened. “I believe that I’ve become more committed to my husband. In fact, my husband is the only one who has always been with me” (Participant VIII). Moreover, the women were found to have more empathy concerning their relationships with others after breast cancer. Especially the women needing support from other women experiencing the same condition reported that they were willing to help women facing breast cancer. “I feel the need to help because of my experiences. Actually, I wanted to talk to somebody having had the same experiences” (Participant VIII).

Increased coping skills

The women described increased coping skills after their struggle against breast cancer. First, they revealed changes in meaning they attached to their problems. “I used to be obsessed with everything, but now I don’t care about anything” (Participant V). Next, the women described a positive point of view and a positive reappraisal of stressors. “I try to think that everything, i.e. whatever I experience, will have a positive outcome. I believe that they have favorable outcomes. I think positive thinking will bring about positive effects” (Participant VII).

Furthermore, some women noted that they can be more tolerant. “I still give importance to problems, but I am able to be more tolerant. I think I can have a different attitude to the issue” (Participant IX).

While the women had difficulty in expressing their negative feelings initially, they easily talked about their feelings after the disease, which could be considered as an important progress. “I didn’t use to tell Serpil, a friend, that I felt uneasy with her. She used to visit me and cause stress. However, now I’ve told her that she disturbs me” (Participant X). Some women also commented that they sought social support for management of stress. “I used to be reserved, but now I don’t. I feel more comfortable. I used to disapprove of telling my husband about a quarrel between me and someone else, but now I can tell about such things comfortably” (Participant IV).

Some women noted that they could reject things after breast cancer: “I didn’t use to say no, but now I can. I simply refuse to do anything which causes me to feel stressed out or I don’t want to do” (Participant XI).

With the changes in their priorities, the women have had time on their hobbies, which they postponed in the past. “Now I have hobbies, which I did not use to spend time on. I used to clean home as soon as I came home … however, now, I do not clean home. Instead, I have taken a course to learn how to play the lute” (Participant XI).

Discussion and Conclusion

The findings of this study provide a specific insight into the nature of PTG in breast cancer survivors in the first post-treatment two years. In addition, the present study contributed to Turkish breast cancer survivors’ understanding the phenomenon of PTG.

The findings of the study showed that breast cancer was a traumatic experience, but that attempts to make sense of cancer during this experience promoted PTG in the early survival phase. Traumatic events result in cognitive processing and deeply influence basic beliefs of individuals about the world and their place and function in the world (24). During this process, searching for meaning is an important part of experiences with cancer. Patients question causal attributions of cancer and the meaning of cancer in their lives (25). In this study, the women mostly identified cancer with death while making sense of this disease. In traditional Turkish culture, cancer is considered as a lethal disease. Facing a life-threatening disease leads patients to become aware of death and their mortality. Individuals realize that routines, habits and priorities lose their importance in the face of death and they can gain new understandings of their lives (26). Health care professionals should provide patients with an opportunity to express their opinions about cancer and guide them to share their feelings, thoughts and experiences to promote a cognitive restructuring process. Health care professionals’ empathy for the patients’ seeking a meaning of life and disease can provide support.

Another way of making sense of traumatic events is the use of religious beliefs. Religious beliefs provide a framework for understanding, managing and coping with traumas and are an important component of growth (15, 27). Concerning this aspect of making sense of cancer, the survivors in this study commented that cancer was a test and a warning sent by God in their lives. According to Muslim culture, diseases are tests given by God and individuals have to question the meaning of these tests and be patient about difficulties caused by diseases. Patience can give patients hope for the future. In addition, it is makes great contributions to personal development. This supports acceptability of life crises and positive changes (27). Health care professionals should realize that patients’ such statements as “cancer is a kind of a test given by God” are a part of their interpretation process of the disease and they should support the patients’ efforts to remain patient, and struggle shaped by this interpretation so that they help patients to find meaning in life while living with the disease.

The women mentioned positive restoring in the value of life, self-value and relationships. Similarly, results of qualitative studies showed survivors experience PTG in appreciation of life, personal strength, and deepened relationships with others (12, 13). Traumatic experiences lead individuals to perform an existential questioning. Responses obtained through this questioning result in changes in the meaning of life and goals (15). After a traumatic experience, individuals become more willing to live and lead a life they have selected instead of the one involving routines only (28). They also become aware of their vulnerability and mortality (15). Growing stronger after suffering helps to acquire a new perceived self and enhances appreciation an individual has for oneself (29). Also, the survivors in the current study noted that their available relationships and bonds with people became more valuable. Likewise, attention has been attracted towards increased depth of relationships after breast cancer in several studies (12, 14). Social support is an important source of coping in Turkish breast cancer patients in the cancer trajectory (16, 30). It is mostly provided by family members during diagnosis and treatment processes. Struggling against breast cancer, a traumatic experience, strengthens relationships (5). Traumatic experiences can lead individuals to become more honest while telling about their emotions and thoughts (15, 28). These experiences also help individuals become more aware of their own sensitivities, which encourages them to be more affectionate. In fact, the participants in the present study described willingness to help others. It is striking that the participants having had the need for help from others with the same experiences in the breast cancer journey were eager to provide such support. This finding reflects a deficiency in care for cancer patients in Turkey.

Another finding of this study was enhanced coping skills. Coping with difficulties led by a trauma means acquisition of new coping skills in life. In fact, with a traumatic event, people become aware of their own vulnerabilities and strengths, which results in development of their coping skills (29). The women in this study also commented that they were able to express their feelings better, reject things and have a positive attitude to life and new interests thanks to changes in their priorities and their increased self-value. Similarly, several studies draw attention to increased problem solving and positive thinking skills and developing new interests (12, 13, 31). Improvements like increased self-respect, being more assertive and tolerant, feeling more powerful and more confident help women with breast cancer to be able to cope with stress and conflicts (32). Health care professionals should question the nature of PTG in breast cancer survivors, help them recognize positive psychosocial changes in their lives and use these changes as a source of coping with negative effects of cancer.

The interviews were conducted on 13 breast cancer survivors in the extended phase. Although data saturation was considered to have been achieved, inclusion of survivors from different backgrounds could have improved the generalizability of the results.

The results of this study revealed that breast cancer survivors experience positive restoring in the first post-treatment two years. Making sense of cancer promotes PTG after breast cancer. Further studies focusing on each aspect of PTG separately and explaining the predictors of PTG may provide valuable insights for an effective survivorship care.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the participants for their contributions to the study.

Footnotes

Ethics Committee Approval: Ethics committee approval was received for this study from the Ethics Committee of Dokuz Eylül University (2150-GOA, 2015/15-14)

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from patients who participated in this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - F.Ş.İ.; Design - F.Ş.İ.; Supervision - F.Ş.İ., B.Ü.; Resources - F.Ş.İ.; Materials - F.Ş.İ.; Data Collection and/or Processing - F.Ş.İ.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - F.Ş.İ., B.Ü.; Literature Search - F.Ş.İ., B.Ü.; Writing Manuscript - F.Ş.İ.; Critical Review - F.Ş.İ., B.Ü.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society, 2017. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2017–2018. Atlanta: Available from: URL: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2017-2018.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ministry of Health of the Republic of Turkey. Health statistics yearbook 2010. Available from: URL: http://sbu.saglik.gov.tr/Ekutuphane/kitaplar/saglikistatistikleriyilligi2010.pdf.

- 3.Landmark BT, Wahl A. Living with newly diagnosed breast cancer: A qualitative study of 10 women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40:112–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linley PA, Joseph S. Positive change following trauma and adversity: a review. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17:11–21. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.İnan FŞ, Üstün B. Breast cancer and posttraumatic growth. J Breast Health. 2014;10:75–78. doi: 10.5152/tjbh.2014.1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychol Inq. 2004;15:1–18. doi: 10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zoellner T, Maercker A. Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology-a critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26:626–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9:455–471. doi: 10.1007/BF02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lelorain S, Bonnaud-Antigna A, Florin A. Long term posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: prevalence, predictors and relationships with psychological health. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17:14–22. doi: 10.1007/s10880-009-9183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mols F, Vingerhoets AJ, Coebergh JWW, Poll-Franse LV. Well-being, posttraumatic growth and benefit finding in long-term breast cancer survivors. Psychol Health. 2009;24:583–595. doi: 10.1080/08870440701671362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hefferon K, Grealy M, Mutrie N. Posttraumatic growth in life threatening physical illness: A systematic review of qualitative literature. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;14:343–378. doi: 10.1348/135910708X332936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barthakur MS, Sharma MP, Chaturvedi SK, Manjunath SK. Posttraumatic growth in women survivors of breast cancer. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016;22:157–162. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.179609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fallah R, Keshmir F, Kashani FL, Azargashb E, Akbari ME. Post-traumatic growth in breast cancer patients: a qualitative phenomenological study. Middle East Journal of Cancer. 2012;3(2–3):35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuchiya M, Horn S, Ingham R. Positive changes in Japanese breast cancer survivors: a qualitative study. Psychol Health Med. 2013;18:107–116. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.686620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. The foundations of posttraumatic growth: an expanded framework. In: Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, editors. The Handbook of Posttraumatic Growth: Research and Practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inan FŞ, Günüşen NP, Üstün B. Experiences of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients in Turkey. J Transcult Nurs. 2016;27:262–269. doi: 10.1177/1043659614550488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris BA, Campbell M, Dwyer M, Dunn J, Chambers SK. Survivor identity and post-traumatic growth after participating in challenge-based peer-support programmes. Br J Health Psychol. 2011;16:660–674. doi: 10.1348/2044-8287.002004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroevers MJ, Helgeson VS, Sanderman R, Ranchor AV. Type of social support matters for prediction of posttraumatic growth among cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2010;19:46–53. doi: 10.1002/pon.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez KA, Willis DG. Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:726–735. doi: 10.1177/1049732304263638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahlberg K, Dahlberg H, Nyström M. Reflective lifeworld research. Sweden: Studentlitteratur; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrow R, Rodriguez A, King N. Colaizzi’s descriptive phenomenological method. The Psychologist. 2015;28:643–644. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications Ltd; 1985. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenberg M. Cognitive processing in trauma: the role of intrusive thoughts and reappraisals. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1995;25:1262–1296. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.1995.tb02618.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor EJ. Whys and wherefores: adult patient perspectives of the meaning of cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1995;11:32–40. doi: 10.1016/S0749-2081(95)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG. Posttraumatic Growth in Clinical. Practice NY: Routledge; 2013. pp. 121–127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw A, Joseph S, Linley A. Religion, spirituality, and post-traumatic growth: a systematic review. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture. 2005;8:1–11. doi: 10.1080/1367467032000157981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG, Cann A, Hanks E. Positive outcomes following burden: paths to posttraumatic growth. Psychol Belg. 2010;50:125–143. doi: 10.5334/pb-50-1-2-125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Janoff-Bulman R. Posttraumatic growth: three explanatory models. Psychol Inq. 2004;15:30–34. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cebeci F, Yangin HB, Tekeli A. Life experiences of women with breast cancer in south western Turkey: a qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Helgeson VS. Corroboration of growth following breast cancer: ten years later. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2010;29:546–574. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.5.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kucukkaya PG. An exploratory study of positive life changes in Turkish women diagnosed with breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]