Abstract

Cancer is rapidly becoming a public health crisis as a result of the continued growth and ageing of the global population and will greatly affect resource-limited low- to middle-income countries. It is widely acknowledged that research should be conducted within countries that will bear the greatest burden of disease, and Africa has the unparalleled opportunity to lead the way in developing clinical trials to improve the health of its countries. In 2018, the inaugural Global Congress on Oncology Clinical Trials in Blacks was organized to address the global challenges of clinical trials for oncology among black populations. During this event, researchers, scientists, and advocates participated in a town hall meeting where they explored the status of oncology clinical trials in Africa using the SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) approach. Participants discussed noteworthy successes, significant barriers, and opportunities to address gaps in developing a sustainable clinical research framework. Many comments centered on the lack of funding and inadequate infrastructure affecting most African countries. Others noted important successes, such as thriving collaborations among institutions and improved political commitment in support of clinical research. The main objectives of the town hall session were to share knowledge on and discuss advantages and disadvantages of conducting clinical research in Africa. These discussions are invaluable in developing interventions and policies that improve clinical research capabilities in Africa.

INTRODUCTION

There is a need for oncology clinical trials in blacks globally. Blacks are disproportionately affected by cancer worldwide, although black populations constitute only approximately 17% of the world population (> 1 billion). For example, blacks in the United States have the highest morbidity, highest mortality, and shortest survival in most cancers compared with other racial/ethnic groups.1 Blacks experience significant disparities in prostate, breast, colorectal, cervical, and oral and pharyngeal cancers. The cancer burden seen in US blacks is a microcosm of the burden of cancer seen in blacks globally, especially in Africa. For example, our team has documented the significant burden of prostate cancer in blacks connected by the transatlantic slave trade, including blacks in the Caribbean, Africa, and Europe.2,3 We have also reported on the rising burden of cancer in sub-Saharan African countries.4

Given the disproportionate burden of cancer experienced by blacks, it is important to have a significant number of blacks participate in cancer clinical trials globally. There are numerous benefits to participating in clinical trials, including access to new approaches that may not be available outside the clinical trial setting, exposure to more effective approaches, access to regular medical attention from a team comprising clinicians and researchers, being among the first to benefit from new methods, and helping other people in the future.5 However, there are also possible risks associated with medical research, including the following: new drugs or procedures under study may not be better than standard care, new treatments may have unexpected adverse effects or risks that are worse compared with those from standard care, participants in randomized trials are not able to choose the approach they receive, health insurance and managed care providers may not cover all patient care costs in a study, and participants may be required to make more visits to the physician than they would if they were not in a clinical trial.5 Unfortunately, given these risks and other barriers, the accrual of patients to clinical trials continues to be a significant challenge.

The lack of representation of blacks in clinical trials complicates the ability to effectively address cancer in these populations. Given the global challenges of oncology clinical trials in black populations, the Global Congress on Oncology Clinical Trials in Blacks was proposed and inaugurated in 2018.

The inaugural Global Congress on Oncology Clinical Trials in Blacks was organized to foster a global community of experts who will develop effective approaches for improving the representation of blacks in clinical trials around the world. The congress was held from November 14 to 16, 2018, in Lagos, Nigeria. Holding the conference in Nigeria was advantageous for several reasons: Nigeria is the most populous black country, Nigerians constitute the largest population of Africans in the diaspora, and Nigeria was a significant source population of US blacks through the transatlantic slave trade. The conference was organized by several international organizations and institutions, including the University of Florida, the Prostate Cancer Transatlantic Consortium, Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, the Association for Good Clinical Practice in Nigeria, and the African-Caribbean Cancer Consortium.

The goals of the congress as follows: provide opportunities for mutual learning, knowledge transfer, and collaboration among oncology clinical trial scientists, clinicians, sponsors, pharmaceutical companies, and government agencies; promote transdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approaches for oncology clinical trials in black populations; advance the engagement, recruitment, and retention of black populations for oncology clinical trials; identify cost-effective technologies to accelerate oncology clinical trials in blacks globally; facilitate networking among individuals involved in all aspects of oncology clinical trials in blacks; facilitate the development of a global community of practice to address common challenges in the engagement, recruitment, and retention of blacks for oncology clinical trials; and develop a comprehensive strategic plan for oncology clinical trials in blacks.

A tangible outcome of this clinical trials congress was the identification of a sustainable and culturally responsive infrastructure needed for clinical trial enterprise in blacks, including human capital; financing/funding mechanisms; effective recruitment, enrollment, and retention approaches; information systems; regulatory pathways; and institutional collaborations.

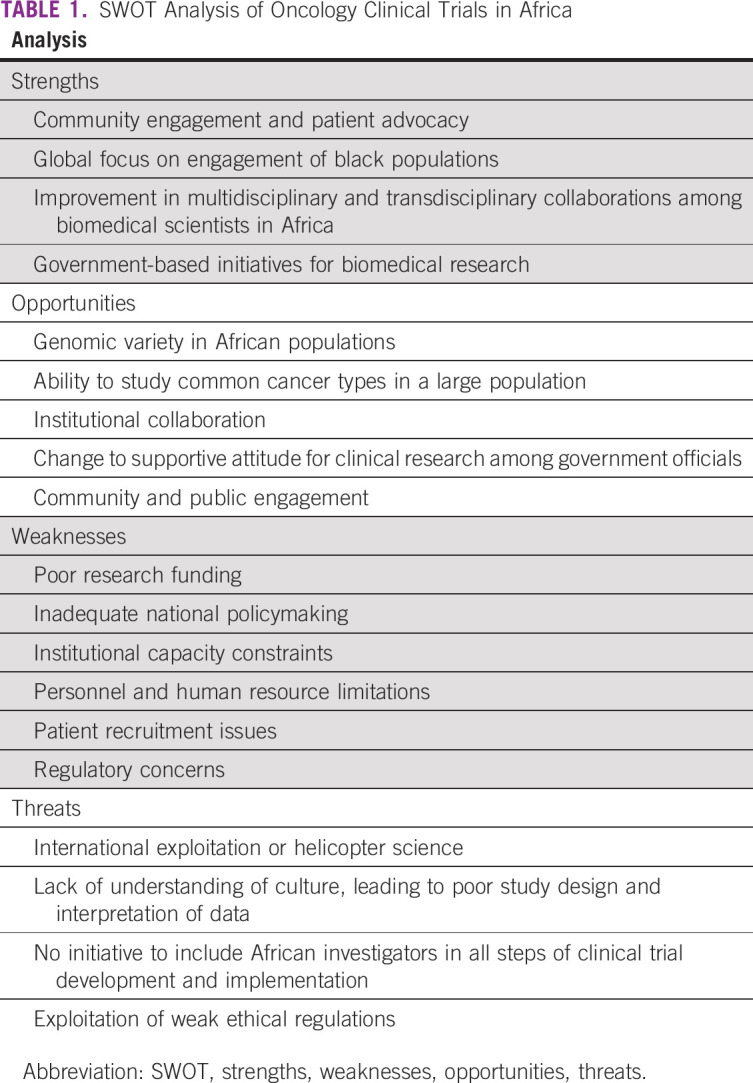

A town hall session was held as part of the Global Congress on Oncology Clinical Trials in Blacks to conduct a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis of clinical trials for black populations in Africa (Table 1). A SWOT analysis is a strategic planning tool used to evaluate the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats involved in a project. Once the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats faced by blacks in Africa relative to oncology clinical trials are identified, the next step is to create a strategic plan by answering the following questions: How can we use each strength? How can we stop each weakness? How can we exploit each opportunity? How can we defend against each threat?

TABLE 1.

SWOT Analysis of Oncology Clinical Trials in Africa

SWOT ANALYSIS REPORT

Strengths

Strengths refer to the internal conditions in Africa that are helpful to implementing clinical trials in blacks. The strengths identified by town hall participants included community engagement, trust, patient advocacy, and global focus on the engagement of black populations. The connection of clinicians and scientists to their respective communities is strong in Africa. This strong community engagement translates to trust of investigators, which facilitates the recruitment and retention of patients for clinical trials. For example, a familial cohort study of West African men in Nigeria and Cameroon recruited > 500 men within a few months.6,7 In contrast, recruiting blacks for biomedical research in the United States is often challenging.8 Another strength of oncology clinical trials in African blacks is the emergence of patient advocacy, especially in female cancers. The rise of patient advocacy in Africa has led to a more informed and educated population. This includes advocacy by cancer survivors, community leaders, family members, and nongovernmental organizations. Also, the practice of including patient advocates and community leaders in biomedical research is increasing, which is enhancing the quality of these studies.

Another notable strength is improvement in multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary collaborations among biomedical scientists in Africa. This has greatly facilitated the team science as well as the synergistic expertise needed for clinical trials in Africa. Another advantage of these collaborations is shared resources and infrastructure.

For example, the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa consists of 13 research and academic institutions from multiple regions in Africa dedicated to strengthening research infrastructure and capacity and developing collaborative research training programs. These institutions are facilitating a productive environment for research on priority issues present in developing countries and creating networks of trained and accomplished scientists.9 Another example is the Prostate Cancer Transatlantic Consortium (CaPTC). CaPTC Nigeria comprises > 15 institutions and > 50 investigators in Nigeria. The group has developed regional areas of centers of excellence and has successfully leveraged the expertise and resources of collaborating investigators and institutions to apply for and attract extramural funding, including US National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute awards. CaPTC Nigeria team members actively leverage the WhatsApp platform, the Web, and social media for scholarship collaboration as well as training programs.

In addition, there is slight progress with respect to government-based initiatives for biomedical research. In Nigeria, the Nigerian Federal Ministry of Health has established the Nigeria Institute of Medical Research, which provides facilities for research, develops structures for dissemination, and enables training and education. Another example is the Nigeria Tertiary Education Trust Fund, an intervention to critically address some of the challenges faced in training and education. The Nigeria Tertiary Education Trust Fund was established to ensure that universities receive necessary resources, which includes funding, training and development, and project management.10

Finally, the participants of the town hall session remarked on the change in attitude within the government and among the public regarding clinical research. There has been recent progress in government interest in cancer clinical research. More officials understand that the research capability of a country is essential to development in health and medicine. At the Global Congress on Oncology Clinical Trials in Blacks, the director general of the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control, Mojisola Christianah Adeyeye, MD, provided the keynote speech highlighting the importance of partnering with regulatory bodies to improve the standard of clinical research. In addition, in 2017, Nigeria Institute of Medical Research appointed an advisory board on research funding. The purpose of the committee is to attract funding from both local and international research communities to ultimately improve the health care in Nigeria.11 In addition, local communities are beginning to recognize the benefits of clinical research. Patients and advocates are spreading awareness about the positive impact clinical trials create when conducted in local settings. Clinical research brings access to care, such as disease screening, treatment, and management. With increased community engagement and public awareness, patient recruitment and retention rise, allowing researchers to reach target accrual in a timely manner.

Weaknesses

Weaknesses refer to the internal conditions in Africa that are harmful to implementing clinical trials in blacks. During the town hall session, participants noted several issues that limit the implementation of clinical research in developing countries. Clinical trials are prone to several challenges related to intrinsic problems in governance, culture, and practices, such as inadequate national policymaking, institutional capacity constraints, personnel and human resource limitations, patient recruitment issues, regulatory concerns, and poor research funding.

Lack of funding is arguably the most glaring factor that stunts the growth of research in African countries. For instance, despite the recent increased focus on medical and clinical research, government grants totaled US$200,000 in Nigeria, US$8 million in The Gambia, and US$79 million in South Africa in 2010, compared with US$114 billion in the United States and US$3 billion in the United Kingdom.12 Unfortunately, there has been a lack of advocacy to promote science and research for proper national budgetary allocation and external funding. Governments need to commit to legislative reform, planning, and funding for research activities. In addition, when research institutions are awarded funding, public concern rises regarding the management of grant money, which can lead to reduced support for clinical research. Therefore, government officials are pressured to increase oversight and financial transparency, which leads to policies that generate redundancy in paperwork and affect timelines as a result of the increase in administrative duties.

Another major barrier, a consequence of poor funding, is the relatively inadequate physical infrastructure in Africa compared with developed countries. Some structural challenges that affect research facilities in Africa include the following: irregular power supply, especially affecting studies that require biobanking, which can lead to loss of samples, extended timelines, and increased costs; inadequate Internet connectivity, which reduces access to online resources such as online journals, protocol development, statistical expertise, and database management13; poor accessibility because of dilapidated road networks, leading to reduced access for patient populations and logistic issues; and unavailable or poorly maintained equipment.

Accompanying physical capacity issues, research institutions have a limited number of trained research personnel, from administrative support to researchers. In Africa, there is a dearth of human resources necessary for the administrative, governing, financial, and management functions needed to develop and sustain competitive research platforms.14 Additionally, there are few African scientists trained in research, a problem aggravated by the inability to retain quality researchers and scientists from other countries or other occupations (ie, brain drain). Without trained and experienced investigators, there are a limited number of mentors for junior investigators. There is also concern that senior investigators feel threatened by their junior counterparts, leading to slackness in mentoring, especially if they fear being surpassed, because they may not be as adept in new technologic or research advances as junior investigators.15 Competition among various cadres of researchers may be a cultural issue, with clinicians and basic scientists claiming superiority of relevance, thereby stunting congeniality and a good research atmosphere. Furthermore, there are few career paths in place at research centers and universities to attract and retain skilled researchers. More career opportunities are needed at every stage of learning, from junior internships to postdoctoral fellowships, in addition to attractive positions with competitive salaries and benefits.16

Another barrier concerns study procedures, primarily in participant recruitment and ethical review. Unfortunately, there exist factors that limit the potential number of participants for clinical research in Africa. For example, some community physicians are wary of collaborating with major institutions because of fear of losing their patients. Another challenge is communicating with community gatekeepers, such as tribal leaders and traditional healers, and gaining permission to recruit participants. These delays result in failure to meet patient recruitment deadlines, increased costs, and termination of clinical studies. Issues concerning national and institutional regulatory bodies are also important and can be limiting. The WHO African Regional Office discovered that 36% of member countries had no research ethics committees.17 In countries that did have research ethics committees, the committees met infrequently, had limited funding, and involved members with inadequate training in human research ethics. The lack of standard guidelines and operating procedures weakens the integrity of clinical research. Clinical trials will need oversight of regulatory bodies, like National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control and the National Health Research Ethics Committee in Nigeria, that are compliant with good clinical practice and quality assurance.

Opportunities

Opportunities refer to the external conditions in Africa that are helpful to implementing clinical trials in blacks. There are many opportunities to grow the field of clinical research and clinical trials in African countries. The main requirements to unlock the potential of establishing a strong oncology clinical trial platform involve understanding the significance of the genomic variety and cancer types present in the African population, embracing institutional collaboration, and taking advantage of the current increased governmental interest in clinical research.

The population in Africa provides a unique opportunity to gain improved biologic insight into cancer and develop effective clinical interventions. The African genome is known to be diverse. This genetic variation may lead to the discovery of mutations that were previously deemed uncommon and unimportant in cancer research.18 This translates to the development of clinical research and clinical trials that can effectively address cancer disparities and improve the current understanding of cancer biology, leading to the development of improved targeted therapies and better clinical outcomes. Furthermore, certain cancers, such as lung, colorectal, breast, and prostate cancers, disproportionately affect men and women of African descent and are usually aggressive and difficult to treat when diagnosed. For example, compared with other races/ethnicities, black women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, a particularly aggressive form of the disease with poor survival rates. The mortality rate for prostate cancer is more than twice as high in black men compared with other races/ethnicities.19 In the case of advanced prostate cancer, there is a clinical unmet need for more accurate and standardized reporting of metastatic biopsies because of poor access to metastatic tissue.20 Because men in Africa tend to be diagnosed at advanced stages, there is opportunity for investigators to understand the variants of advanced prostate cancer, which has significant implications for management and treatment.

The successful development of clinical trials in Africa depends on the establishment or strengthening of research capacity and infrastructure. This is best done through collaboration among all institutions, such as nonprofit organizations, universities, and health care facilities, as seen in the United States and other developed countries. BIO Ventures for Global Health, a nonprofit global health organization, launched the African Access Initiative, a program focused on bringing together oncology companies with governments and hospitals in Africa to foster cancer research and increase availability of cancer treatment. Through African Access Initiative, BIO Ventures for Global Health launched the African Consortium for Cancer Clinical Trials to develop cancer clinical trials led by investigators in Africa. The goals of African Consortium for Cancer Clinical Trials include increasing access to cancer treatment through clinical trials; supporting African investigators and their research; building clinical trial capacity, including training and acquisition of laboratory equipment; and encouraging support from pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies in drug research and development in Africa.21 An upgrade in infrastructure and capacity will strengthen research facilities in Africa and make them better contenders for research funding. Arguably, the most important benefit of forming partnerships is the central support for facilities. It would be advantageous to have a single principal body that ensures research centers and their investigators meet Good Clinical Practice and Good Clinical Laboratory Practice standards and have support for administrative aspects, such as protocol writing, institutional review board submission, and budget development. Creation of new relationships among investigators and institutions also provides opportunities for new projects, and such collaboration on research studies could increase sample sizes; reduce time for study completion; and help develop standardized approaches to data collection, management, and analysis.

Threats

Threat refers to the external conditions in Africa that are harmful to implementing clinical trials in blacks. Threats to oncology clinical trials in Africa largely result from the perceptions and interests of foreign nations that conflict with those of locals. If the interests of natives are not taken into consideration, the opinions and preferences of those disconnected from locals will take precedent.

Much can be learned from research exploits of tribal and native populations, because they too have had to develop research practices to respect and protect their interests. Otherwise, abuses such as so-called helicopter science ensue. Specifically, international scientists briefly and often hurriedly enter a country or community, conduct research, and leave without adequately engaging with local health care providers, researchers, or community leaders.

Subsequently, the international researchers benefit from the study findings in tangible ways, including publications, additional grants, and promotions/tenure, whereas the populations studied do not benefit, and in many cases are actually harmed, because they are often characterized in ways that are out of context and culturally insensitive.

Such agnostic, insensitive treatment threatens oncology clinical trials in Africa by also perpetuating a lack of understanding of the cultures of African populations. Consideration should be given as to how best to develop long-term working relationships among international collaborators and African researchers. Shared knowledge, resources, and professional benefits should be pursued. Of the scientific and clinical knowledge that may predominate in international programs, training and skill building should be provided to African academic and clinical partners. By working to understand the culture of each group, Africans gain knowledge of the scientific research process while the international scientists learn and appreciate pertinent cultural nuances. When this threat is not combated, the study design, data analysis, and interpretation of the results lack cultural relevance, portray an incomplete picture, and are largely not generalizable to the very patient group or community under study.

In addition to the importance of governing, regulatory, and ethical board considerations, funding is paramount. International research entities must be willing to share government and federal grant allocations and/or pharmaceutical funding to support oncology clinical trials in Africa. Shared funding is needed to develop long-term partnerships, foster community and patient engagement, and support clinical research and oncology clinical trials. African investigators need to be part of the budget discussions and must be appropriately and equitably compensated for patient recruitment as well as intellectual and scientific contributions to study design and implementation. Equitable salaries for all investigators involved in data collection, management, analysis, and interpretation should be established before commencement of the research. This will help prevent discrimination and abuse of power on the part of international interests.

As actualized during the Global Congress on Oncology Clinical Trials in Blacks, international collaborations can thrive if the widely accepted standard research practices and ethical principles that are adhered to throughout the world are also implemented, monitored, and regulated in Africa. Many of the ethical considerations that guide international research should be fostered in Africa. Institutional review boards, advisory bodies, international policies like Helsinki, and native guiding principles for fair, humane, and collegial interaction should be a part of common practice. The informed consent process should be put into practice and maintained throughout.

The global pressure to race for a cure for cancer set forth by initiatives such as the NIH Cancer Moonshot Research Initiative could unduly influence international researchers to cut corners, rush, and be less adherent to strict guidelines. Such threats to the quality of oncology clinical trials in Africa might give rise to and perpetuate abuses that would otherwise be nonexistent if African investigators were involved throughout the research process and protective of their interests.

In general, threats to oncology clinical trials in Africa demand surveillance and monitoring, and course correction is necessary if research abuses arise. Diligence must be maintained to protect the interests of Africans in international collaborations. Systems of checklists, policies and procedures, quality assurance, assessments and audits, and shared decision making can help to ensure all interests are considered, power differentials are balanced, and research is conducted that favors the health and well-being of all involved.

DISCUSSION

There are some promising signs of progress in clinical research and clinical trials in Africa, but there are many barriers preventing Africa from becoming a global contender. Cancer research development in Africa needs a strategic approach, primarily focused on building a framework that nurtures research. Attention should be paid to government policy changes, collaboration across institutions and professions, and public engagement.

Furthermore, private and public sectors, health industries, and governmental agencies within African countries need to take the initiative and make the commitment to invest in research with dedicated staff and budgets. Such strategies should include the following: develop and strengthen regional networks of institutions to combine resources and skills; create advocacy groups that rally support and communicate the positive impact of clinical research; provide education and training in needed research expertise, such as data management, statistics, and ethics; establish professional career development pathways, such as fellowships; and train and support administrative personnel in navigating grant and funding procedures and policies. If clinical trials are to flourish, Africa needs to play the major role in strengthening and sustaining its own infrastructure and capacity.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Adaora Ezeani, Folakemi Odedina, Omolara Fatiregun

Administrative support: Adaora Ezeani, Folakemi Odedina, Desiree Rivers

Collection and assembly of data: Adaora Ezeani, Folakemi Odedina, Desiree Rivers, Omolara Fatiregun

Data analysis and interpretation: Adaora Ezeani, Folakemi Odedina, Desiree Rivers, Titilope Akinremi

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jgo/site/misc/authors.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2016-2018. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odedina FT, Ogunbiyi JO, Ukoli FA. Roots of prostate cancer in African-American men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:539–543. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Odedina FT, Akinremi TO, Chinegwundoh F, et al. Prostate cancer disparities in black men of African descent: A comparative literature review of prostate cancer burden among black men in the United States, Caribbean, United Kingdom, and West Africa. Infect Agent Cancer. 2002;4(suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-4-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morhason-Bello IO, Odedina F, Rebbeck TR, et al. Challenges and opportunities in cancer control in Africa: A perspective from the African Organisation for Research and Training in Cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:e142–e151. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Cancer Institute: Clinical Trials Questions and Answers for Prospective Participants, 2019. https://dtc.cancer.gov/trials/information.htm.

- 6. Kaninjing ET, Dagne G, Atawodi SE, et al: Modifiable risk factors implicated in prostate cancer mortality and morbidity among Nigerian and Cameroonian men. Cancer Health Disparities [epub ahead of print on May 5, 2019] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oladoyinbo CA, Akinbule OO, Bolajoko OO, et al: Risk factors for prostate cancer in West African men: The familial cohort study. Cancer Health Disparities [epub ahead of print on May 27, 2019]

- 8.Hussain-Gambles M, Atkin K, Leese B. Why ethnic minority groups are under-represented in clinical trials: A review of the literature. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;12:382–388. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2004.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ezeh AC, Izugbara CO, Kabiru CW, et al. Building capacity for public and population health research in Africa: The Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA) model. Glob Health Action. 2010 doi: 10.3402/gha.v3i0.5693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Onyeike VC, Eseyin EO. Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFund) and the management of university education in Nigeria. Glob J Educ Res. 2014;13:63–72. doi: 10.4314/gjedr.v13i2.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gbenga-Mustapha O. NIMR inaugurates advisory board on research funding. http://thenationonlineng.net/nimr-inaugurates-advisory-board-research-funding/

- 12. Nigerian Institute of Medical Research: Development of a Strategic Plan (2011-2015). http://www.ianphi.org/_includes/documents/sections/toolkit/Nigeria_NIMR_STRATEGIC_PLAN.pdf.

- 13.Chu KM, Jayaraman S, Kyamanywa P, et al. Building research capacity in Africa: Equity and global health collaborations. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zumla A, Huggett J, Dheda K, et al. Trials and tribulations of an African-led research and capacity development programme: The case for EDCTP investments. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:489–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumwenda S, Niang EHA, Orondo PW, et al. Challenges facing young African scientists in their research careers: A qualitative exploratory study. Malawi Med J. 2017;29:1–4. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v29i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitworth JA, Kokwaro G, Kinyanjui S, et al. Strengthening capacity for health research in Africa. Lancet. 2008;372:1590–1593. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61660-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kass NE, Hyder AA, Ajuwon A, et al. The structure and function of research ethics committees in Africa: A case study. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e3. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Green A: African DNA could hold the key to a cure for cancer. https://www.cancerhealth.com/article/african-dna-hold-key-cure-cancer.

- 19.DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:211–233. doi: 10.3322/caac.21555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beltran H, Tomlins S, Aparicio A, et al. Aggressive variants of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:2846–2850. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dent J, Manner CK, Milner D, et al: Africa’s emerging cancer crisis: A call to action. https://bvgh.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Africas-Emerging-Cancer-Crisis-A-Call-to-Action.pdf.