Abstract

Background

A recent clinical trial showed that an immediate transition to very low nicotine content (VLNC) cigarettes, compared with a gradual transition, produced greater reductions in smoking behavior, smoke exposure, and dependence. However, there was less compliance with the instruction to smoke only VLNC cigarettes in the immediate versus gradual reduction condition. The goal of this study was to test whether nicotine reduction method alters subjective ratings of VLNC cigarettes, and whether subjective ratings mediate effects of nicotine reduction method on smoking behavior, smoke exposure, dependence, and compliance.

Methods

This is a secondary analysis of a randomized trial conducted across 10 sites in the United States. Smokers (n = 1250) were randomized to either a control condition, or to have the nicotine content of their cigarettes reduced immediately or gradually to 0.04 mg nicotine/g of tobacco during a 20-week study period. Participants completed the modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire (mCEQ).

Results

After Week 20, the immediate reduction group scored significantly lower than the gradual reduction group on multiple subscales of the mCEQ (ps < .001). The Satisfaction subscale of the mCEQ mediated the impact of nicotine reduction method on smoke exposure, smoking behavior, dependence, compliance, and abstinence. Other subscales also mediated a subset of these outcomes.

Conclusions

An immediate reduction in nicotine content resulted in lower product satisfaction than a gradual reduction, suggesting that immediate reduction further reduces cigarette reward value. This study will provide the Food and Drug Administration with information about the impact of nicotine reduction method on cigarette reward value.

Implications

These data suggest that an immediate reduction in nicotine content will result in greater reductions in cigarette satisfaction than a gradual reduction, and this reduction in satisfaction is related to changes in smoking behavior and dependence.

Introduction

A mandated reduction in the nicotine content of cigarettes may reduce the prevalence of smoking by reducing the addictiveness of combusted cigarettes. Recent clinical trials investigating the impact of nicotine reduction in current smokers have had promising results—very low nicotine content (VLNC; 0.04 mg nicotine/g tobacco) cigarettes reduce the number of cigarettes smoked per day, reduce toxicant exposure, decrease nicotine dependence, and increase the likelihood of making a quit attempt compared to normal nicotine content (NNC; 15.5 mg nicotine/g tobacco) cigarettes.1–9 Indeed, in 2018, the Food and Drug Administration issued an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking announcing their intention to pursue a nicotine reduction policy and asking for input on a number of topics related to a potential policy in the United States.10

One of the topics on which the Food and Drug Administration solicited input was the impact of the method of nicotine reduction (gradual vs. immediate) in cigarettes. An immediate reduction would require all cigarettes in the United States to meet the VLNC product standard by a certain date, whereas a gradual reduction would require that cigarettes meet a series of standards with incrementally lower nicotine content over a certain length of time. The largest clinical trial to date investigating nicotine reduction method (ie, gradual vs. immediate) was published in 2018 and showed that an immediate transition to VLNC cigarettes produced greater reductions in toxicant exposure, number of cigarettes smoked per day, dependence, and a greater number of smoke-free days than a gradual reduction.1 However, immediate reduction produced higher rates of participant attrition and less compliance with smoking only the VLNC cigarettes than gradual reduction.1

We do not know whether the method of reduction (ie, gradual vs. immediate) impacts subjective responses to VLNC cigarettes. The subjective effects of smoking are often assessed using the modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire (mCEQ), which assesses several dimensions of subjective effects including Satisfaction, Psychological Reward, Aversion, Enjoyment of Respiratory Tract Sensations, and Craving Relief.11 Four of these subscales (Satisfaction, Psychological Reward, Enjoyment of Respiratory Tract Sensations, Craving Relief) are thought to reflect positive reinforcing effects of smoking and be associated with reinforcing efficacy and abuse liability, and one subscale (Aversion) reflects the acute punishing effects (eg, nausea, dizziness) associated with smoking.11–14 VLNC cigarettes are rated as less satisfying on a version of the mCEQ modified to ask about research cigarettes when participants try them in a laboratory setting.15 Reduced ratings for VLNC cigarettes compared to NNC cigarettes on the mCEQ in a within-subjects design are also predictive of fewer choices to use VLNC cigarettes in a laboratory-based choice task.16 Reduced subjective ratings on the mCEQ suggest that VLNC cigarettes hold reduced reinforcing efficacy compared to traditional cigarettes currently on the market. Thus, understanding the impact of nicotine reduction method on cigarette subjective effects would provide information to the Food and Drug Administration about whether the two methods have differential effects on reinforcing efficacy and abuse liability.

The primary goal of this article was to test whether the method of nicotine reduction (gradual vs. immediate) impacts subjective effect ratings of VLNC cigarettes, as measured by the mCEQ. We conducted a secondary analysis utilizing data from a large, recently published clinical trial investigating the impact of method of nicotine reduction on changes in smoking behavior and smoke exposure.1 On the basis of the primary data, which showed a larger reduction in smoking and smoke exposure associated with immediate reduction, we hypothesized that immediate reduction would result in lower scores on the mCEQ subscales that reflect positive reinforcement. We also ask whether key baseline variables, gender and nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR) moderate the impact of reduction method on subjective effects. Gender has been shown to be related to smoking subjective effects,17 and NMR is a biomarker for the rate of nicotine metabolism, which might be expected to impact nicotine reduction outcomes18 (but see Mercincavage et al.19). Second, we were also interested in whether differential subjective effects observed between the gradual and immediate groups might help explain (ie, mediate) the effect of nicotine reduction method on key outcomes such as smoking behavior, smoke exposure, dependence, and compliance with the study cigarettes.

Study Design

This is a secondary analysis based on data from a randomized, double-blind trial conducted across 10 sites in the United States. For detailed methods and results of the primary outcomes, see the primary paper.1 Briefly, participants were assigned in a 2:2:1 ratio to receive either immediate nicotine reduction, gradual nicotine reduction, or NNC control condition, respectively. After a 2-week baseline period during which participants smoked their usual brand of cigarette, participants were randomized to their treatment conditions for 20 weeks. Participants in all groups received a supply of study cigarettes equivalent to 200% of their baseline number of cigarettes per day (CPD) to allow for compensatory smoking if needed and in case of a missed visit. Participants in the immediate group received Spectrum research cigarettes20 with 0.4 mg nicotine/g tobacco (VLNC; n = 503). Participants in the gradual group received Spectrum research cigarettes with a new nicotine content every 4 weeks (Weeks 0, 4, 8, 12, and 16) such that the final research cigarette was the same VLNC cigarette the immediate group received (n = 498). Nicotine contents for the gradual group were 15.5 (control), 11.7, 5.2, 2.4, and 0.4 (VLNC) mg nicotine/g tobacco. Participants in the control group received Spectrum cigarettes with 15.5 mg nicotine/g tobacco for the entire experimental period (n = 249). Participants and experimenters were blind to the nicotine content of assigned cigarettes, and participants received menthol or non-menthol cigarettes matched to their preference. The control group is not included in the main statistical analyses because the primary aim was to compare the two reduction groups. However, we have included the control group in figures for visual comparison and included statistical comparison to the control group in the Supplementary Materials. Participants were asked not to smoke any cigarettes other than their assigned cigarettes, and a semi-bogus pipeline was used to incentivize compliance. Participants in all groups were told that a spot urine collected at each visit would be randomly chosen for analysis to determine whether they had been compliant, and a bonus would be paid to them if they had been compliant ($1000). In actuality, bonus payments were provided when participants achieved urine total nicotine equivalents (TNEs) at or less than 12 nmol/mL at Weeks 18 and 20, when both groups were assigned to the lowest nicotine content. All participants in the control group were paid bonuses.

Participants

Current smokers (n = 1250) were recruited from 10 sites including Duke University, Johns Hopkins University, Mayo Clinic, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Oregon Research Institute, University of California San Francisco, University of Minnesota, University of Minnesota-Duluth, University of Pennsylvania, University of South Florida, and University of Texas. Eligibility criteria included being at least 18 years old, smoking at least five CPD (biochemically verified by expired carbon monoxide [CO] level greater than 8 ppm or urinary cotinine of greater than 1000 ng/mL), and breath alcohol level less than 0.02% at screening. Exclusion criteria included intention to quit smoking in the next 30 days; use of other tobacco products, including e-cigarettes, on more than 9 days out of the past 30; exclusive use of roll-your-own cigarettes; prior exposure to reduced nicotine content cigarettes; serious or unstable psychiatric or medical illness; positive urine screen for illicit drugs other than cannabis; and breast feeding, pregnancy, or planning to become pregnant.

Procedures

Participants completed a 2-week baseline period before being assigned to their conditions for 20 weeks. Participants smoked ad libitum during the baseline period with their usual brand and were then asked to exclusively use Spectrum research cigarettes during the 20-week experimental period. Participants attended weekly laboratory visits for the first 4 weeks after randomization, and then biweekly for the next 16 weeks. Throughout the study, participants completed daily phone calls assessing use of study and non-study cigarettes via an interactive voice response system. At the study visits, a variety of physiological and subjective assessments were administered (see primary paper for a full list). Relevant to this article, participants completed an mCEQ11 weekly for the first 4 weeks, and then again in 4-week increments (Weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20). Participants were instructed when answering the questions to think about their experiences with the assigned cigarettes since their last scheduled visit. Thus, at Week 0 the questionnaire refers to usual brand. At all other weeks, the questionnaire refers to the study cigarette assignment for the previous time period. Participants provided biological samples (eg, CO, first morning void urine samples) to assess for biomarkers of nicotine and toxicant exposure. First void urine was analyzed for TNEs, which was assessed to determine compliance to VLNC cigarettes. Two TNE criteria for compliance were used. Participants with TNEs less than or equal to 6.41 nmol/mL were classified as being compliant with exclusively using the VLNC cigarettes.21 A secondary, less stringent criterion of less than or equal to 12 nmol/mL was used to classify participants as being mostly compliant with the study cigarettes but allows for a low level of noncompliance.1 Participants also completed the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)22 and the Brief Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM).23

Data Analysis

Analyses focused on assessing (1) whether gradual versus immediate reduction produced different subjective cigarette ratings, and (2) whether subjective cigarette ratings mediated the impact of nicotine reduction method on smoking behavior, dependence, compliance, and abstinence. To understand whether the two methods of nicotine reduction impacted subjective ratings of VLNC cigarettes, five subscales were analyzed as dependent variables (Satisfaction, Psychological Reward, Aversion, Enjoyment of Respiratory Tract Sensations, and Craving Reduction). The mCEQ used for study cigarettes during the trial as well as subscale scoring information can be found in the supplement. These subscales are empirically derived from a confirmatory factor analysis.11 The four positive subscales are positively correlated with each other, and weakly negatively correlated with the Aversion subscale.11

Analyses utilized linear regression to test whether the gradual and immediate groups differed on each subscale of the mCEQ. Missing data were handled using multiple imputation with the Markov Chain Monte Carlo method. Sensitivity analyses were conducted for last observation carried forward (see Supplementary Table 1). The primary unadjusted analysis controlled for baseline values of the mCEQ scale based on usual brand, and a secondary adjusted analysis controlled for baseline, study site, and baseline variables, which were different between treatment arms at p less than .20 (employment, FTND, serum nicotine metabolic ratio). The primary unadjusted analysis is reported here, but the pattern of results was the same for the adjusted analysis (see Supplementary Table 2). This analysis examined two timepoints: First, mCEQ ratings at Week 20 were compared across the two experimental groups. This analysis tests mCEQ ratings of VLNC cigarettes at the end of the trial (after 5 months of research cigarette use). A secondary analysis tested differences between mCEQ ratings at Week 4 for the immediate group and Week 20 for the gradual group. This analysis holds length of VLNC cigarette use constant between both experimental groups by testing mCEQ ratings after each group had 4 weeks of VLNC cigarette use. Comparisons of both the gradual and immediate groups to the control group at Weeks 4 and 20 are included in Supplementary Table 3.

We also tested whether gender or serum NMR of 3'-hydroxycotinine to cotinine moderated the effect of nicotine reduction method on mCEQ subscales using the same multiple imputation and regression models. Similar to previous studies examining the NMR,24–26 a binary NMR variable was used that divided the lowest quartile NMR (Q1 = 0.235) from the higher three quartiles. All tests were two-sides and p-values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Note that no correction was applied on the p-values of individual tests because subjective cigarette ratings were exploratory endpoints in the original trial.1

The mediation analysis used a single-mediation model to test whether each mCEQ subscale at Week 20 served as a mediator of treatment effects on several outcomes, also assessed at Week 20.27 Outcomes of interest included measures of smoking and smoke exposure (expired CO, total [study + non-study] CPD, study CPD), dependence (FTND after removing the CPD item, WISDM primary subscales, WISDM secondary subscales, total WISDM score), compliance with only using the study cigarettes (meeting a urinary TNE criterion for compliance less than or equal to 12 nmol/mL, meeting a more stringent criterion of less than or equal to 6.41 nmol/mL), and CO-verified (CO < 6 ppm) 7-day abstinence (seven self-reported continuous smoke-free days before Week 20). Only observed data were used (ie, no imputation) in the mediation analysis, and sample size for each outcome is included in Supplementary Table 4. The mediation effect was estimated as the product of two regression coefficients: the impact of treatment (gradual vs. immediate) on the mCEQ subscale, and the impact of the mCEQ subscale on each outcome adjusting for treatment.27 The bootstrap method (bootstrap size = 1000) was used to construct the 95% confidence interval for the estimated mediation effect, as recommended by previous research.27 A 95% confidence interval not including zero indicates a significant mediation effect. An additional mediation analysis was performed using the change score of the outcome variables for those that have a relevant baseline measurement (Supplementary Table 5).

Results

Impact of Method of Nicotine Reduction on Cigarette Subjective Ratings

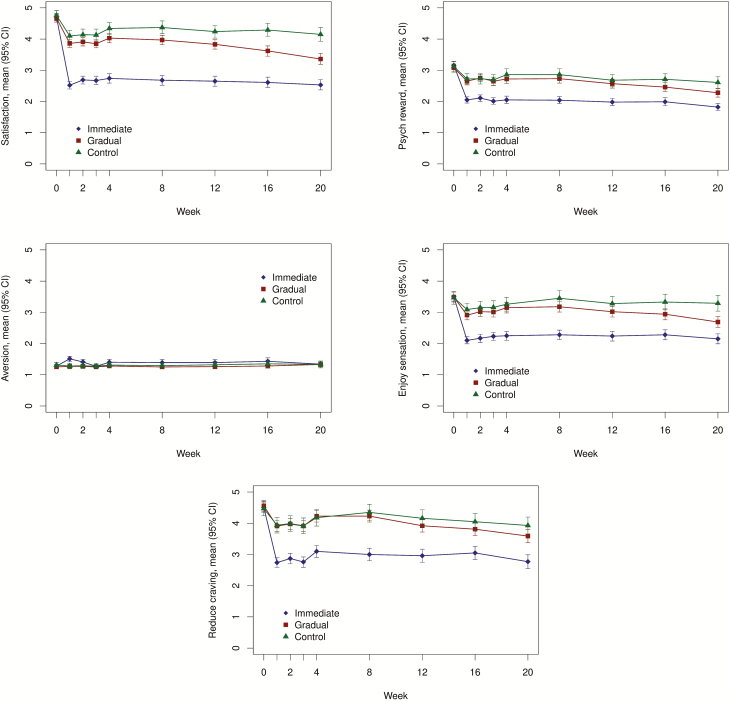

Figure 1 shows the impact of nicotine reduction method on each of the five mCEQ subscales at each timepoint. Individuals in the immediate condition had reduced ratings on four mCEQ subscales that are indicative of positive effects: Satisfaction, Psychological Reward, Enjoyment of Respiratory Tract Sensations, and Craving Relief, compared with the gradual group (ps < .01; Table 1). This pattern was the same both when Week 4 in the immediate group was compared to Week 20 in the gradual group and when Week 20 in the immediate group as compared to Week 20 in the gradual group. The analysis adjusting for additional baseline covariates (Supplementary Table 1) and the sensitivity analysis using last observation carried forward (Supplementary Table 2) showed similar results. Additional analyses comparing the two nicotine reduction groups with the control group (Supplementary Table 3) showed that the immediate reduction group rated the study cigarettes significantly lower than the control group at Weeks 4 and 20 for the Satisfaction, Psychological Reward, Enjoyment of Respiratory Tract Sensations, and Craving Relief. The gradual reduction group’s ratings were only significantly lower than the control group for these subscales at Week 20, when they had experienced reduction to the lowest nicotine content. The gradual group had reduced Satisfaction subscale ratings compared to the control group at Week 20, but there were not significant differences for the other subscales. Neither gender nor NMR significantly moderated the impact of method of reduction on CES subscales (interaction ps > .05).

Figure 1.

Means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each subscale in each treatment group across the 20 treatment weeks. Figures display observed data only (ie, no imputation). Week 0 refers to usual brand for all groups.

Table 1.

Results of analyses comparing mCEQ subscales in the immediate vs. gradual groups

| Measures | Week 20 immediate vs. Week 20 gradual | Week 4 immediate vs. Week 20 gradual | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference Immediate vs. gradual (95% CI) | p | Mean difference Immediate vs. gradual (95% CI) | p | |

| Satisfaction | −1.00 (−1.21 to −0.80) | <.00001* | −0.67 (−0.88 to −0.45) | <.00001* |

| Psych reward | −0.52 (−0.68 to −0.36) | <.00001* | −0.23 (−0.38 to −0.08) | .0025* |

| Aversion | 0.02 (−0.09 to 0.13) | 0.75 | 0.08 (−0.04 to 0.20) | 0.20 |

| Enjoy sensation | −0.63 (−0.84 to −0.42) | <.00001* | −0.48 (−0.70 to −0.26) | <.0001* |

| Craving relief | −0.87 (−1.15 to −0.60) | <.00001* | −0.49 (−0.77 to −0.22) | .0006* |

Bolded p values with asterisks indicate significance. Linear regression adjusted for baseline mCEQ subscale score (usual brand). Missing data were imputed by multiple imputation method. CI = confidence interval; Enjoy sensation = Enjoyment of Respiratory Tract Sensations; Psych reward = Psychological Reward.

Subjective Effects as a Mediator

The primary paper for this trial includes the treatment effects for each of the outcomes examined in the mediation analysis.1Table 2 shows the mediation effects of each mCEQ subscale on each of the key outcomes. The effects of treatment on total CPD, Study CPD, FTND, total WISDM score, primary WISDM subscales, and secondary WISDM subscales were all significantly mediated by the Satisfaction, Psychological Reward, Enjoyment of Respiratory Tract Sensations, and Craving Relief subscales of the mCEQ. CO was significantly mediated by the Satisfaction, Psychological Reward, and Enjoyment of Respiratory Tract Sensations subscales. CO-verified abstinence was mediated by the Satisfaction and Enjoyment of Respiratory Tract Sensations subscales. These mediated pathways all operated in the expected direction, such that the immediate reduction condition was associated with reduced mCEQ subscale scores compared to the gradual reduction condition, and in turn, the lower mCEQ subscale scores were associated with reduced smoking behavior and exposure to a smoking-related biomarker in the immediate group. Both TNE criteria for compliance with the study cigarettes were mediated by the Satisfaction and the Craving Relief subscales. Specifically, compared to gradual reduction, the immediate reduction condition was associated with reduced satisfaction and craving relief, which in turn, was associated with increased noncompliance. The Aversion subscale did not significantly mediate any outcomes. Analyses testing whether mCEQ subscales mediated change scores for these outcomes were consistent with those reported in the main text that utilized absolute scores (Supplementary Table 5).

Table 2.

Results of mediation analyses

| Dependent variable | Potential mediator | a | b | ab | 95% CI for ab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO (ppm) | Satisfaction | 0.83 | 0.71 | 0.59 | (0.20 to 1.01)* |

| Psych reward | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.26 | (0.02 to 0.64)* | |

| Aversion | −0.02 | −0.58 | 0.01 | (−0.08 to 0.09) | |

| Enjoy sensation | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.25 | (0.04 to 0.55)* | |

| Craving relief | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0.24 | (−0.05 to 0.56) | |

| Total CPD | Satisfaction | 0.83 | 1.70 | 1.42 | (0.84 to 2.20)* |

| Psych reward | 0.45 | 1.60 | 0.73 | (0.27 to 1.37)* | |

| Aversion | −0.02 | −0.31 | 0.01 | (−0.08 to 0.15) | |

| Enjoy sensation | 0.54 | 1.37 | 0.74 | (0.36 to 1.30)* | |

| Craving relief | 0.82 | 0.77 | 0.63 | (0.28 to 1.05)* | |

| Study CPD | Satisfaction | 0.83 | 2.33 | 1.94 | (1.34 to 2.77)* |

| Psych reward | 0.45 | 2.13 | 0.97 | (0.49 to 1.67)* | |

| Aversion | −0.02 | −1.15 | 0.02 | (−0.12 to 0.22) | |

| Enjoy sensation | 0.54 | 1.84 | 1.00 | (0.55 to 1.64)* | |

| Craving relief | 0.82 | 1.19 | 0.98 | (0.60 to 1.50)* | |

| FTND without CPD | Satisfaction | 0.83 | 0.28 | 0.23 | (0.16 to 0.34)* |

| Psych reward | 0.45 | 0.30 | 0.13 | (0.08 to 0.21)* | |

| Aversion | −0.02 | 0.13 | 0.00 | (−0.02 to 0.02) | |

| Enjoy sensation | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.13 | (0.07 to 0.21)* | |

| Craving relief | 0.82 | 0.12 | 0.10 | (0.04 to 0.17)* | |

| WISDM primary | Satisfaction | 0.83 | 0.31 | 0.26 | (0.17 to 0.38)* |

| Psych reward | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.24 | (0.15 to 0.35)* | |

| Aversion | −0.02 | 0.34 | −0.01 | (−0.04 to 0.04) | |

| Enjoy sensation | 0.54 | 0.28 | 0.15 | (0.08 to 0.24)* | |

| Craving relief | 0.82 | 0.23 | 0.19 | (0.11 to 0.30)* | |

| WISDM secondary | Satisfaction | 0.83 | 0.28 | 0.24 | (0.16 to 0.35)* |

| Psych reward | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.27 | (0.16 to 0.37)* | |

| Aversion | −0.02 | 0.31 | −0.01 | (−0.03 to 0.04) | |

| Enjoy sensation | 0.54 | 0.29 | 0.16 | (0.09 to 0.25)* | |

| Craving relief | 0.82 | 0.17 | 0.14 | (0.09 to 0.21)* | |

| WISDM total | Satisfaction | 0.83 | 3.22 | 2.68 | (1.76 to 3.91)* |

| Psych reward | 0.45 | 6.22 | 2.83 | (1.72 to 4.04)* | |

| Aversion | −0.02 | 3.55 | −0.06 | (−0.37 to 0.44) | |

| Enjoy sensation | 0.54 | 3.14 | 1.70 | (0.98 to 2.73)* | |

| Craving relief | 0.82 | 2.12 | 1.74 | (1.05 to 2.63)* | |

| Compliance (TNE ≤ 12 nmol/mL) | Satisfaction | 0.83 | 0.14 | 0.12 | (0.03 to 0.22)* |

| Psych reward | 0.45 | 0.11 | 0.05 | (−0.01 to 0.12) | |

| Aversion | −0.02 | −0.37 | 0.01 | (−0.04 to 0.05) | |

| Enjoy sensation | 0.54 | 0.06 | 0.03 | (−0.02 to 0.10) | |

| Craving relief | 0.82 | 0.22 | 0.18 | (0.09 to 0.30)* | |

| Compliance (TNE ≤ 6.41 nmol/mL) | Satisfaction | 0.83 | 0.11 | 0.09 | (0.00 to 0.17)* |

| Psych reward | 0.45 | 0.04 | 0.02 | (−0.05 to 0.08) | |

| Aversion | −0.02 | −0.36 | 0.01 | (−0.04 to 0.05) | |

| Enjoy sensation | 0.54 | 0.04 | 0.02 | (−0.03 to 0.08) | |

| Craving relief | 0.82 | 0.18 | 0.15 | (0.07 to 0.25)* | |

| CO-verified (<6 ppm) 7 cigarette-free days | Satisfaction | 0.83 | −0.52 | −0.43 | (−1.22 to −0.11)* |

| Psych reward | 0.45 | −0.31 | −0.14 | (−0.84 to 0.07) | |

| Aversion | −0.02 | 0.21 | 0.00 | (−1.05 to 0.17) | |

| Enjoy sensation | 0.54 | −0.52 | −0.28 | (−0.75 to −0.11)* | |

| Craving relief | 0.82 | −0.31 | −0.25 | (−1.05 to 0.02) |

All mediators and outcomes are assessed at Week 20. Bolded confidence intervals with asterisks indicate significance. = effect of gradual vs. immediate reduction on mCEQ subscale, and a positive a indicates that the gradual group had a higher average score on the relevant mCEQ subscale than the immediate group; = effect mCEQ subscale on dependent variable, and a positive indicates that the relevant mCEQ subscale was positively associated with the dependent variable controlling for the treatment effect; a = mediation effect, and estimates for a that are significantly different than 0 indicate the mCEQ subscale mediates the effect of the treatment on the dependent variable. CO = carbon monoxide; CPD = cigarettes per day; Enjoy Sensation = Enjoyment of Respiratory Tract Sensations; FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; mCEQ = modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire; Psych reward = Psychological Reward; TNE = total nicotine equivalents; WISDM = Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives.

Discussion

The present data show that an immediate reduction in nicotine content produces a more drastic change in the subjective effects of VLNC cigarettes than gradual reduction including product Satisfaction, Psychological Reward, Enjoyment of Respiratory Tract Sensations, and Craving Relief. The immediate group reported lower scores on these subscales than the gradual group both at the end of the study (Week 20 both groups) and when comparing the two groups after each had 4 weeks of experience with the lowest nicotine content cigarettes (Week 4 immediate vs. Week 20 gradual). Scores on these subscales for the immediate group were remarkably stable for the duration of time participants experienced VLNC cigarettes. However, both groups had significantly reduced scores on these subscales compared to the control group at Week 20. There are several possible reasons for differential product satisfaction between nicotine reduction methods. First, it is possible that smokers may have rated the VLNC cigarettes relative to the preceding cigarette that they experienced. For the immediate group, VLNC cigarettes would have been rated relative to usual brand, whereas for the gradual group, VLNC cigarettes would have been rated relative to an intermediate nicotine content. Second, it is possible that as a result of experience with intermediate nicotine contents, participants in the gradual group were less likely to discriminate the change in the subjective effects of even lower nicotine content cigarettes. Prior research has shown that it is difficult for smokers to discriminate VLNC cigarettes from other low nicotine contents.28 Finally, it is possible that experience with a gradual reduction may shift the dose–response curve, such that VLNC cigarettes now maintain more reinforcement value for the gradual group.

The primary paper for this trial reported that there was a greater reduction in smoking behavior and smoke exposure associated with an immediate reduction, and here we report that an immediate reduction also resulted in a greater reduction in subjective effects like product satisfaction. The mediation analysis presented here suggests that greater reduction in cigarette subjective effects observed in the immediate group, like satisfaction, is related to greater reductions in smoking, smoke exposure, and dependence for this group. As noted later, subjective effects and the other outcomes were assessed at the same timepoint, making it difficult to determine the direction of the effect. However, product satisfaction as a mechanism for changes in smoking behavior is consistent with data, showing that smoking interventions that target product satisfaction increase cessation.29 We were underpowered to test the impact of nicotine reduction method on abstinence given that the rate of abstinence at Week 20 was low (7% in immediate vs. 3% in gradual). Nonetheless, we report that the Satisfaction mCEQ subscale mediated the relationship between method of nicotine reduction and abstinence at Week 20. Satisfaction and Craving Relief subscales were also related to noncompliance among the immediate group, which is consistent with a previous analysis showing that low satisfaction with VLNC cigarettes is associated with noncompliance.30 These data suggest that noncompliance may have been more common in the immediate group at least partially because immediate reduction results in less satisfaction with VLNC cigarettes. If NNC cigarettes are not available in the real-world marketplace, it is possible that smokers who find VLNC cigarettes to be unsatisfying may quit cigarettes, be motivated to seek illicit NNC cigarettes, or may choose to use other tobacco products like e-cigarettes. Non-cigarette tobacco products like e-cigarettes are likely to hold greater relative reinforcement value once the reinforcement value of cigarettes has been reduced.3

Conclusions and Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the mCEQ is completed after extended experience with the VLNC cigarettes, and thus may be less reflective of acute primary reinforcing effects than in a laboratory setting. Second, for the mediation analysis, both the mCEQ subscales and the outcomes of interest were collected at the same timepoint. Thus, we cannot confirm the temporal order of the associations between the mediators and outcomes. It is possible that smokers who experienced greater reductions in smoking behavior and dependence may have inferred that they were less satisfied with the product based on their experiences, which could have influenced their mCEQ ratings. In addition, because we were only able to test mediation at Week 20, the gradual and immediate groups have different lengths of experience with the VLNC cigarettes when completing the mCEQ that was used for this analysis. Third, as reported in the primary paper, there was greater attrition in the immediate group than the gradual group, which may have been related to differences in subjective effects. However, it is likely that if we had been able to include the participants who withdrew from the study, the differences observed here between the gradual and immediate groups on cigarette subjective effects would have been even larger. Finally, we do not know how the subjective effects of VLNC research cigarettes used in this trial (Spectrum) will compare to commercially made VLNC cigarettes. It is possible that commercially made VLNC would be more satisfying than Spectrum cigarettes, reducing the influence of subjective effects on smoking behavior.

These data suggest that an immediate reduction in the nicotine content of cigarettes is likely to result in a greater reduction in the positive subjective effects of VLNC cigarettes than a gradual reduction. Furthermore, these data suggest that greater changes in subjective effects like product satisfaction are related to larger changes in smoking behavior and dependence as well as reduced compliance when nicotine is reduced immediately. Overall, these data suggest that if a mandated reduction in nicotine content is implemented, an immediate nicotine reduction policy is likely to result in the greatest improvement in public health given that it is likely to result in greater changes in product satisfaction, and in turn, smoking behavior and exposure. However, immediate reduction might also produce greater interest in illicit cigarettes and other tobacco products because it will produce a greater reduction in VLNC cigarette reinforcement value.

Funding

The research reported in this article was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products (U54DA031659). Salary support during the preparation of this article was provided by U54DA031659, K01DA043413, K01DA047433, R36DA045183. The biostatistical analyses were carried out in the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resources of the Masonic Cancer Center, supported in part by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support grant P30CA077598. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or Food and Drug Administration.

Declaration of Interests

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the co-investigators, students, fellows, staff, and participants involved in the Center for the Evaluation of Nicotine in Cigarettes.

References

- 1. Hatsukami DK, Luo X, Jensen JA, et al. . Effect of immediate vs gradual reduction in nicotine content of cigarettes on biomarkers of smoke exposure: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(9):880–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Donny EC, Denlinger RL, Tidey JW, et al. . Randomized trial of reduced-nicotine standards for cigarettes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(14):1340–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smith TT, Hatsukami DK, Benowitz NL, et al. . Whether to push or pull? Nicotine reduction and non-combusted alternatives—two strategies for reducing smoking and improving public health. Prev Med. 2018;117:8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith TT, Cassidy RN, Tidey JW, et al. . Impact of smoking reduced nicotine content cigarettes on sensitivity to cigarette price: Further results from a multi-site clinical trial. Addiction. 2017;112(2):349–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benowitz NL, Dains KM, Hall SM, et al. . Smoking behavior and exposure to tobacco toxicants during 6 months of smoking progressively reduced nicotine content cigarettes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21(5):761–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Benowitz NL, Hall SM, Stewart S, Wilson M, Dempsey D, Jacob P 3rd. Nicotine and carcinogen exposure with smoking of progressively reduced nicotine content cigarette. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(11):2479–2485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hatsukami DK, Kotlyar M, Hertsgaard LA, et al. . Reduced nicotine content cigarettes: effects on toxicant exposure, dependence and cessation. Addiction. 2010;105(2):343–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Donny EC, Houtsmuller E, Stitzer ML. Smoking in the absence of nicotine: behavioral, subjective and physiological effects over 11 days. Addiction. 2007;102(2):324–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shiffman S, Kurland BF, Scholl SM, Mao JM. Nondaily smokers’ changes in cigarette consumption with very low-nicotine-content cigarettes: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(10):995–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. FDA. FDA announces comprehensive regulatory plan to shift trajectory of tobacco-related disease, death, in Agency to pursue lowering nicotine in cigarettes to non-addictive levels and create more predictability in tobacco regulation. July 28, 2017. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-announces-comprehensive-regulatory-plan-shift-trajectory-tobacco-related-disease-death? [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, Baker CL, et al. . Confirmatory factor analyses and reliability of the modified cigarette evaluation questionnaire. Addict Behav. 2007;32(5):912–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. O’Connor RJ, Lindgren BR, Schneller LM, Shields PG, Hatsukami DK. Evaluating the utility of subjective effects measures for predicting product sampling, enrollment, and retention in a clinical trial of a smokeless tobacco product. Addict Behav. 2018;76:95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arger CA, Heil SH, Sigmon SC, et al. . Preliminary validity of the modified cigarette evaluation questionnaire in predicting the reinforcing effects of cigarettes that vary in nicotine content. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;25(6):473–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shiffman S, Kirchner TR. Cigarette-by-cigarette satisfaction during ad libitum smoking. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118(2):348–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hatsukami DK, Heishman SJ, Vogel RI, et al. . Dose-response effects of spectrum research cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(6):1113–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bergeria CL, Heil SH, Davis DR, et al. . Evaluating the utility of the modified cigarette evaluation questionnaire and cigarette purchase task for predicting acute relative reinforcing efficacy of cigarettes varying in nicotine content. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;197:56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Perkins KA, Karelitz JL, Kunkle N. Sex differences in subjective responses to moderate versus very low nicotine content cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2018;20(10):1258–1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Faulkner P, Ghahremani DG, Tyndale RF, et al. . Reduced-nicotine cigarettes in young smokers: impact of nicotine metabolism on nicotine dose effects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(8):1610–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mercincavage M, Lochbuehler K, Wileyto EP, et al. . Association of reduced nicotine content cigarettes with smoking behaviors and biomarkers of exposure among slow and fast nicotine metabolizers: a nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Richter P, Steven PR, Bravo R, et al. . Characterization of SPECTRUM variable nicotine research cigarettes. Tob Regul Sci. 2016;2(2):94–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Denlinger RL, Smith TT, Murphy SE, et al. . Nicotine and anatabine exposure from very low nicotine content cigarettes. Tob Regul Sci. 2016;2(2):186–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström tolerance questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith SS, Piper ME, Bolt DM, et al. . Development of the brief Wisconsin inventory of smoking dependence motives. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(5):489–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lerman C, Jepson C, Wileyto EP, et al. . Genetic variation in nicotine metabolism predicts the efficacy of extended-duration transdermal nicotine therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;87(5):553–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lerman C, Schnoll RA, Hawk LW Jr, et al. ; PGRN-PNAT Research Group. Use of the nicotine metabolite ratio as a genetically informed biomarker of response to nicotine patch or varenicline for smoking cessation: a randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(2):131–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patterson F, Schnoll RA, Wileyto EP, et al.. Toward personalized therapy for smoking cessation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial of bupropion. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(3):320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annu Rev Psychol. 2007;58:593–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Perkins KA, Kunkle N, Karelitz JL, Michael VC, Donny EC. Threshold dose for discrimination of nicotine via cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2016;233(12):2309–2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rose JE, Behm FM, Westman EC, Kukovich P. Precessation treatment with nicotine skin patch facilitates smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(1):89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nardone N, Donny EC, Hatsukami DK, et al.. Estimations and predictors of non-compliance in switchers to reduced nicotine content cigarettes. Addiction. 2016;111(12):2208–2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.