Abstract

Spatial segregation of proteins to neuronal axons arises in part from local translation of mRNAs that are first transported into axons in ribonucleoprotein particles (RNPs), complexes containing mRNAs and RNA binding proteins. Understanding the importance of local translation for a particular circuit requires not only identifying axonal RNPs and their mRNA cargoes, but also whether these RNPs are broadly conserved or restricted to only a few species. Fragile X granules (FXGs) are axonal RNPs containing the Fragile X related family of RNA binding proteins along with ribosomes and specific mRNAs. FXGs were previously identified in mouse, rat, and human brains in a conserved subset of neuronal circuits but with species-dependent developmental profiles. Here we asked whether FXGs are a broadly conserved feature of the mammalian brain and sought to better understand the species-dependent developmental expression pattern. We found FXGs in a conserved subset of neurons and circuits in the brains of every examined species that together include mammalian taxa separated by up to 160 million years of divergent evolution. A developmental analysis of rodents revealed that FXG expression in frontal cortex and olfactory bulb followed consistent patterns in all species examined. In contrast, FXGs in hippocampal mossy fibers increased in abundance across development for most species but decreased across development in guinea pigs and members of the Mus genus, animals that navigate particularly small home ranges in the wild. The widespread conservation of FXGs suggests that axonal translation is an ancient, conserved mechanism for regulating the proteome of mammalian axons.

Keywords: RNA binding proteins, local protein synthesis, axonal translation, RRID AB_2737297, RRID AB_10805421, RRID AB_528262, RRID AB_2278530

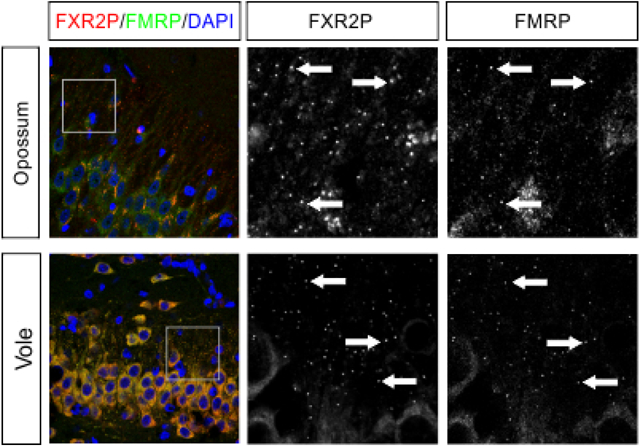

Graphical Abstract

Fragile X granules, axonal mRNA granules containing translational regulators including the Fragile X protein FMRP, are consistently expressed in specific brain circuits in diverse mammalian species including opossums and voles. This pattern suggests that FMRP-regulated axonal translation is an ancient, conserved mechanism for modulating the proteome of mammalian axons.

Introduction

Local protein synthesis is a broadly conserved mechanism for controlling spatiotemporal patterns of protein expression in both eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells and is critical for cell division, migration, and morphology (Buxbaum, Haimovich, & Singer, 2015; Martin & Ephrussi, 2009; Nevo-Dinur, Nussbaum-Shochat, Ben-Yehuda, & Amster-Choder, 2011). Restricting local translation to the appropriate cellular compartment at the correct developmental timepoint requires correct positioning of ribonucleoprotein particles (RNPs), complexes that contain mRNAs and the RNA binding proteins that control their translation. In neurons, local translation is supported by a variety of RNPs that can differ in their prevalence, mRNA cargoes, and RNA binding protein composition depending upon developmental stage, neuronal cell type, and subcellular location. The large number of neuronal RNPs reflects the diversity of neuronal morphology and function seen throughout the nervous system. However, since brain size and structure can vary drastically across species, some of these RNPs may support specialized functions in only one or a few species. The most interesting RNPs therefore are those whose expression is conserved across different species, since they are compelling candidates for supporting fundamental neurobiological functions.

Fragile X granules (FXGs) are a class of neuronal RNPs first identified in mice and rats that exhibit remarkable specificity in the circuits in which they are found, the RNA binding proteins they contain, and the mRNAs with which they associate (Akins et al., 2017; Akins, LeBlanc, Stackpole, Chyung, & Fallon, 2012; Christie, Akins, Schwob, & Fallon, 2009; Chyung, LeBlanc, Fallon, & Akins, 2018). Within the subset of neurons that express them, FXGs are found only in axons and are excluded from the somatodendritic domain (Akins et al., 2017, 2012; Christie et al., 2009). FXGs contain one or more of the Fragile X related (FXR) family of RNA binding proteins: FMRP (Fragile X mental retardation protein), FXR2P, and FXR1P. FMRP, which is mutated in the autism-related disorder Fragile X syndrome (FXS), modulates activity-dependent synaptic protein synthesis and therefore is a critical regulator of experience-dependent circuit refinement in both the developing and adult brain (Bassell & Warren, 2008; Darnell & Klann, 2013). Notably, FXGs associate with a specific subset of FMRP target mRNAs whose protein products modulate the structure and function of presynaptic sites (Akins et al., 2017; Chyung et al., 2018). These FXG properties are conserved in both mice and rats, suggesting these granules may support conserved cellular functions. FXG-regulated local protein synthesis may thus provide a conserved mechanism for regulating neuronal circuit function.

Local translation in axons supports axon outgrowth and synapse formation during development as well as synapse function and plasticity in the adult nervous system (Biever, Donlin-Asp, & Schuman, 2019; Korsak, Mitchell, Shepard, & Akins, 2016; Scarnati, Kataria, Biswas, & Paradiso, 2018; Younts et al., 2016). Defining the ages at which FXGs are found would suggest whether they function primarily in circuit formation or function. Interestingly, the developmental timing of FXG expression differs among species (Akins et al., 2017). In the olfactory bulb, FXGs are found throughout life in both mice and rats. In other forebrain regions, including hippocampus and neocortex, FXGs in mice are only found in juvenile animals during periods of robust experience-dependent circuit refinement. In contrast, in rats FXGs are present in hippocampus throughout life rather than only in juveniles. Importantly, FXGs are also present in adult human hippocampus in the same neuron types as in mice and rats (Akins et al., 2017). FXGs may thus regulate neuronal circuits during development as well as in adulthood in a species-dependent manner.

To elucidate whether FXGs play fundamental roles in the mammalian brain, we asked whether they are conserved in a broad variety of mammalian species and, if so, whether their expression patterns are also conserved or instead vary among species. In particular, we sought to better understand the species-dependent expression of FXGs in the adult hippocampus. To these ends, we examined brain tissue from mammalian species that together cover 160 million years of divergent evolution (Fig. 1). FXGs were present in all these species in a spatial pattern equivalent to that seen in juvenile mice. Interestingly, most of the species expressed FXGs in the adult hippocampus. To better understand the developmental profile of FXG expression, we examined olfactory bulb, cortex, and hippocampus from juveniles and adults of five rodent species. Olfactory bulb and cortex had similar developmental patterns in all these species, even though the absolute abundance of FXGs was species-dependent. In contrast, FXGs were found in both juvenile and adult hippocampal circuits in voles and deer mice (Peromyscus) but were only abundant in juvenile hippocampus in all examined representatives of the Mus genus as well as in guinea pigs. Interestingly, these species also have particularly small natural home ranges. Our results suggest that FXG-regulated local translation is a broadly conserved mechanism for regulating the axonal proteome of select neurons in the mammalian brain. Moreover, this regulation occurs in most species during both developmental and adult periods of experience-dependent circuit refinement.

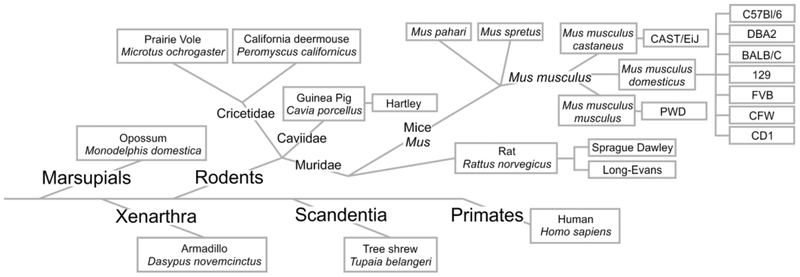

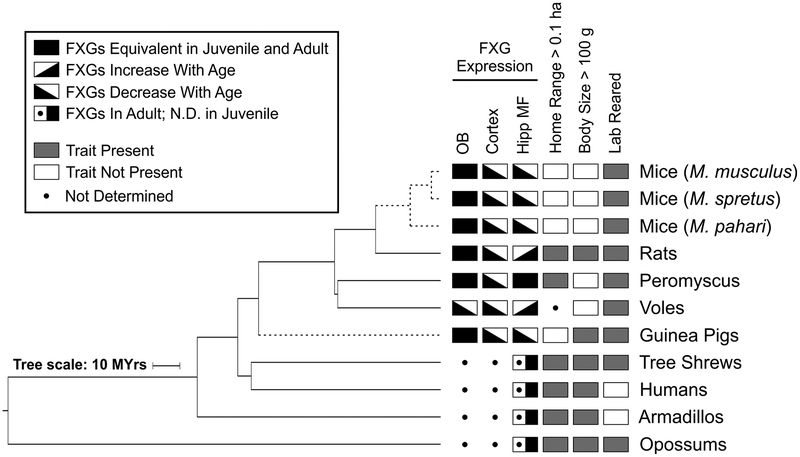

Figure 1. Phylogeny of examined species.

This key depicts the taxonomic relationships among the species investigated in the present study as well as in a past study (Akins et al., 2017). Relationships based on the Open Tree of Life (Hinchliff et al., 2015). See also Fig. 9.

Materials and Methods

Animals:

All work with animals was performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Drexel University and the respective institutions that donated tissue. Pilot studies showed that male and female mice did not exhibit differences in FXG expression or composition; therefore, we used a mix of males and females as indicated in the respective figure and table legends. We collected tissue from the following animals: Mus spretus (SPRET/EiJ), Mus pahari, Mus musculus castaneus (CAST/EiJ), Mus musculus musculus (PWD) (all from Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), and Mus musculus domesticus strains (DBA2, BALB/C, 129, FVB, CFW, CD1; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). Animals were deeply anaesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine/acepromazine before intracardiac perfusion with room temperature HBS (0.1M HEPES, pH 7.4; 150 mM sodium chloride) containing 1 U/mL heparin and 0.5% sodium nitrite followed by perfusion with room temperature PBS (0.1M phosphate, pH 7.4; 150 mM sodium chloride) containing 4% paraformaldehyde. After perfusion, intact brains were carefully removed and postfixed overnight in the perfusate. After washing in PBS, brains were cryoprotected in PBS containing 30% sucrose until the brains sank. Brains were then embedded in OCT medium by rapid freezing and stored at −80 °C until sectioned. Free-floating coronal or sagittal sections of OCT-embedded brains were prepared using a Leica cryostat at 40 μm and either used the same day or stored at 4 °C in PBS containing 0.02% sodium azide.

Perfused brains were generously donated by Dr. Elizabeth Becker (St. Joseph’s University; Peromyscus; line derived from the Peromyscus Genetic Stock Center of the University of South Carolina), Dr. Bruce Cushing (The University of Texas at El Paso; vole), Dr. Jeffery Padberg (University of Central Arkansas; armadillo), Dr. Leah Krubitzer (University of California, Davis; opossum and tree shrew), and Dr. Woody Petry (University of Louisville; tree shrew). Perfused guinea pig brains were purchased from Hilltop Lab Animals (Scottdale, PA). Donated and purchased tissue was perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde prior to being shipped and stored at 4 °C in PBS containing 0.02% sodium azide and processed as above starting with cryoprotection in PBS with 30% sucrose.

Immunohistochemistry:

Tissue was first washed three times in PBS (10 mM phosphate pH 7.4; 150 mM NaCl). To improve antibody accessibility to epitopes in tissue, sections were then heated in 0.01M sodium citrate (pH 6.0) for 10 min at 99 °C. Tissue was then treated with blocking solution [PBST (10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, and 0.3% Triton X-100) and 1% blocking reagent (Roche)] for 30 min to occupy nonspecific binding sites. Sections were then incubated with blocking solution plus primary antibody overnight before being washed for 5 min with PBST. For secondary detection, tissue was incubated with appropriate labelled antibodies in blocking solution for 1 h. Tissue was then washed for 5 min with PBST, mounted in 4% npropylgallate, 85% glycerol, 10 mM phosphate pH 7.4, then coverslipped and sealed with nail polish. Sections were imaged using a Leica SPE confocal microscope.

Antibody Characterization:

| Primary Antibody | Source | Target | RRID | Primary Dilution | Secondary antibody |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse anti-FXR2P | Monoclonal A42 from hybridoma supernatant | Raised against human FXR2P amino acids 12–426; recognizes a single band of the appropriate size by Western and does not cross react with either FMRP or FXR1P (Y. Zhang et al., 1995) | AB_2737297 | 1:300 | Alexa-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 (Life Technologies; 1:1000) |

| Mouse anti-FXR2P | Monoclonal 1G2 from hybridoma supernatant | Raised against recombinant FXR2P residues 414–658. Recognizes a single band of the appropriate size (Zang et al., 2009). | AB_528262 | 1:1000 | Alexa-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 (Life Technologies; 1:1000) |

| Mouse anti-FMRP | Monoclonal 2F5–1 from concentrated hybridoma supernatant | Raised against amino acids 1–204 of human FMRP. Recognizes bands of the appropriate sizes by Western, does not give signal in either blots or sections derived from Fmr1 null mice (Christie et al., 2009; Gabel et al., 2004) | AB_10805421 | 5 μg/ml | Alexa-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG2b (Life Technologies; 1:1000) |

| Rabbit anti-FMRP | Abcam ab17722 | Raised against synthetic peptide within Human FMRP aa 550 to the C-terminus. Recognizes bands of the appropriate sizes by Western, does not cross react with other FXR proteins and does not give signal in materials derived from Fmr1 null mice (Darnell, Fraser, Mostovetsky, & Darnell, 2009; Edbauer et al., 2010) | AB_2278530 | 1:500 | Alexa-conjugated donkey antirabbit (Life Technologies; 1:1000) |

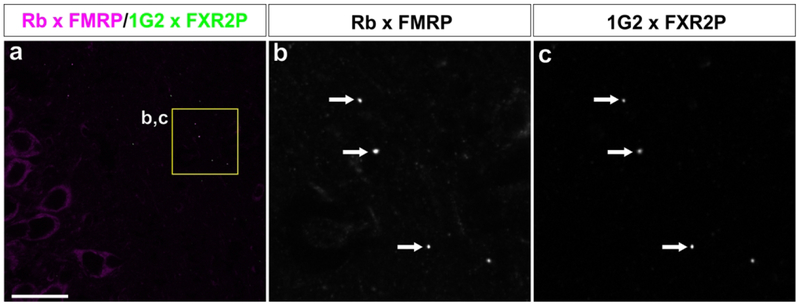

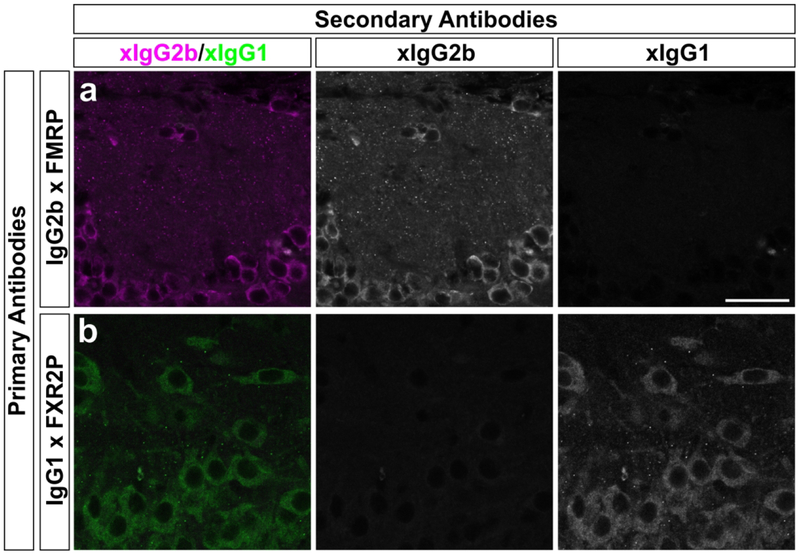

Past studies in mouse and rat tissue have shown the authenticity of the FMRP and FXR2P signal in FXGs as equivalent signal was revealed by multiple antibodies targeting distinct portions of these proteins while the signal for both proteins is absent in the corresponding knockout mouse tissue (Akins et al., 2012; Christie et al., 2009). Although we could not probe knockout tissue from the species included in this study, the 2F5–1 (which recognizes an N terminal sequence of FMRP) and A42 (raised against the N terminus of FXR2P) primary antibodies used throughout this study gave signal across species that was equivalent to that obtained with a rabbit antibody recognizing the C terminus of FMRP and the 1G2 monoclonal antibody against the C terminusof FXR2P (Fig. 2). Moreover, the isotype-specific secondary antibodies were validated to ensure they did not exhibit cross-reactivity with inappropriate immunoglobulin isotypes (Fig. 3).

Figure 2. FXGs are identified by multiple FXR protein antibodies.

(a) Confocal micrograph of P2 guinea pig hippocampus stained with rabbit anti-FMRP (magenta) and 1G2 mouse anti-FXR2P (green) antibodies. Inset depicted in b and c. (b,c) FXGs (arrows) were identified by these antibodies in a pattern indistinguishable from FXGs identified by 2F5–1 mouse anti-FMRP and A42 mouse anti-FXR2P as depicted in the other figures in this manuscript. Scale bar = 40 μm in a; 10 μm in b.

Figure 3. Secondary antibodies do not cross react with inappropriate primary antibodies.

Representative confocal micrographs of P15 C57Bl/6 mouse sections showing (a) olfactory bulb stained with the IgG2b monoclonal antibody 2F5–1 anti-FMRP and (b) hippocampus stained with the IgG1 monoclonal antibody A42 anti-FXR2P. Sections were then incubated with secondaries against both IgG2b and IgG1 primary antibodies. No crossreactive signal was seen in the absence of either primary antibody, validating the fidelity of the secondary antibodies and indicating that FXGs are bona fide sites of colocalization between FMRP and FXR2P signal. Scale bar = 25 μm.

Selection of Brain Regions for Quantification:

For quantification of FXG composition and abundance (see following paragraphs), brain regions were selected for imaging as in previous studies (Akins et al., 2017, 2012; Christie et al., 2009; Chyung et al., 2018). For olfactory bulb, 3–4 glomeruli were imaged from each of 3–6 sections spanning the rostrocaudal extent of the olfactory bulb. These glomeruli were selected for imaging based on their clear definition by surrounding juxtaglomerular cells as visualized with DAPI (notably not by using the FXG signal) and were arbitrarily chosen so as to include glomeruli from the dorsal, ventral, lateral and medial aspects of the olfactory bulb. For frontal cortex, single images were collected from each of 3–5 sections per animal from layers V/VI of motor cortex superficial to the genu of the corpus callosum. For CA3 mossy fibers, single images from each of 3–5 sections per animal were taken of the portion of CA3 (where pyramidal neurons had a clearly ordered laminar structure) most proximal to the dentate gyrus. In guinea pigs, we also acquired images of CA4, where cells were less organized and within the hilus of the dentate gyrus. CA3 associational fibers were imaged (one image from each of 3–5 sections per animal) in superficial stratum oriens.

FXG Composition Quantification:

Fluorescent micrographs of brain sections immunostained for FXR2P and FMRP were collected as above. FXGs were identified based on morphology using FXR2P signal as previously described (Akins et al., 2017, 2012; Christie et al., 2009; Chyung et al., 2018). In these images, each FXR2P-containing FXG was manually annotated as to whether it colocalized with FMRP signal.

FXG Abundance Quantification:

Epifluorescent micrographs of FXR2P immunostaining were captured from three to five sections of each condition (age, species, and brain region as indicated in Results) with a Hamamatsu Orca-R2 camera coupled to a Leica DMI4000 B microscope using a 40x oil objective (NA=1.15). These images were processed using the FIJI build of ImageJ with a rolling ball background subtraction with a radius of 7 pixels followed by a median filter with a radius of 2 pixels. All pixels less than 1.5 standard deviations above the image background intensity were removed from further processing. Auto threshold was set using maximum entropy of the remaining pixels for FXG identification. Granules were counted manually using previously described criteria (Akins et al., 2012; Christie et al., 2009) with pixels inappropriately identified as FXGs (e.g., autofluorescent blood vessels) manually discarded from counts. Graphs and statistical analyses were produced using Prism 6.0 (Graphpad). Quantifications are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Figure Preparation:

Images used in figures were adjusted for brightness, contrast, and gamma using Photoshop CS6 13.0.6 (Adobe). Figures were prepared using Corel Draw X7 (Corel).

Results

FXGs are highly conserved across mammalian taxa

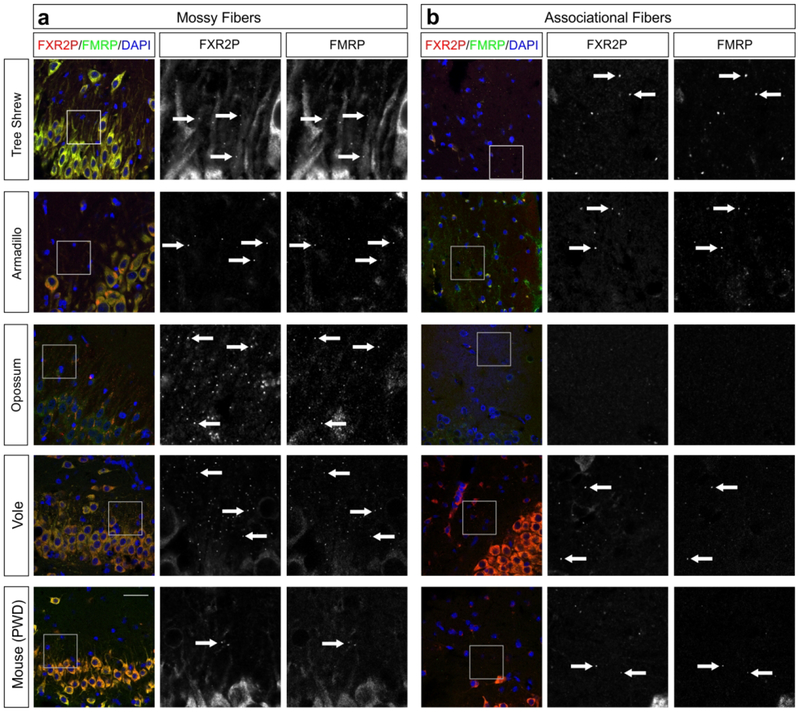

We first asked whether FXGs are broadly conserved by examining hippocampal tissue from adults of a wide range of mammalian species. In the hippocampus of mice, rats, and humans, FXGs are found in two populations of axons – dentate mossy fibers and CA3 associational fibers – but absent from others including the Schaffer collaterals (Akins et al., 2017; Christie et al., 2009). To test the extent of FXG conservation, we immunostained hippocampal sections from adult animals for FXR2P, a necessary component of all FXGs (Christie et al., 2009), and FMRP. Consistent with past studies, FXGs were readily observed in mossy fibers in adults of most examined species, including tree shrews, armadillos, opossums, and voles (Fig. 4). We also observed FXGs in associational fibers in all of these species except opossum. Since we do not have an independent marker of these axons, we could not determine whether this axon population does not contain FXGs in opossums or whether the axons were not present in our specimens. These findings reveal an ancient origin for FXG expression as they were found in brains from a wide taxonomic range, including both placental and non-placental mammals.

Figure 4. FXGs containing FMRP are expressed in the hippocampus in adults of diverse species.

Confocal micrographs of immunostaining for FXR2P (red) and FMRP (green) in (a) mossy fibers and (b) associational fibers in hippocampal tissue from adult armadillo (exact age unknown), tree shrew (P322), opossum (P527–848), vole (P120), and mouse (PWD strain, P120). FXGs were identified in mossy fibers in all species examined and in associational fibers in armadillo, tree shrew, vole, and PWD tissue; FXGs were not detected in associational fibers in opossum. FXGs colocalized with FMRP signal. DAPI (blue) used as a nuclear stain. Arrows indicate FXGs. Scale bar=50 μm, 14 μm in insets. Armadillo n=1 (male); tree shrew n=1 (female); opossum n=3 (2 female, 1 male); vole n=4 (2 male, 2 female); PWD n=5 (1 male, 4 female).

Our past studies of FXGs in the adult mouse brain found few FXGs in the adult hippocampus (Akins et al., 2017; Christie et al., 2009). These studies focused on C57Bl/6 mice, a strain of the Mus musculus domesticus subspecies. To determine whether the absence of FXGs from the adult hippocampus may be a specific feature of M. musculus domesticus, we asked whether FXGs were abundant in the hippocampus of adult PWD mice, a strain of the M. musculus musculus subspecies that diverged from M. musculus domesticus approximately 1 million years ago (Gregorová & Forejt, 2000; Montagutelli, Serikawa, & Guénet, 1991). As with the C57Bl/6 mice, we only rarely detected FXGs indicating that FXGs are not common in adult hippocampus of multiple M. musculus subspecies.

FMRP is a conserved component of hippocampal FXGs

The function and regulation of RNA granules are heavily dependent on the RNA binding proteins found within those granules. FXGs in the mouse forebrain contain FMRP and FXR2P, with a region-selective subset also containing FXR1P (Christie et al., 2009; Chyung et al., 2018). We therefore asked whether FMRP and FXR2P are conserved components of the hippocampal FXGs found in other species. We found that FMRP colocalized with FXR2P in the large majority of FXGs in all of the examined species regardless of the relative FXG abundance in each species (Fig. 4; Table 1). FXR2P and FMRP are therefore conserved components of FXGs.

Table 1. Quantification of FMRP-containing FXGs in hippocampus across species.

FXGs were identified in hippocampal axons of the examined species based on FXR2P immunoreactivity. The percentage and absolute number of these FXGs that also contained FMRP is indicated. For each animal (age and sex as indicated) the number of FXGs represents the summed total across 1–4 sections. Mean (± standard error as appropriate) is indicated for each region/species.

| Mossy Fibers | Associational Fibers | |

|---|---|---|

| Tree Shrew | 100% (40/40; P322 female) | 100% (53/53; P322 female) |

| Armadillo | 89.7% (175/195; adult male) | 98.5% (67/68; adult male) |

| Opossum | 95.9% (116/121; P818 female) | N/A |

| Vole | 99.8 ± 0.2% | 95.8 ± 2.2% |

| 99.3% (140/141; P21 male) | 95.2% (80/84; P21 male) | |

| 100% (145/145; P21 female) | 100% (71/71; P21 female) | |

| 100% (127/127; P120 female) | 92.3% (24/26; P120 female) | |

| Peromyscus | 99.6 ± 0.4% | 97.2 ± 2.8% |

| 98.9% (88/89; P21 female) | 100% (75/75; P21 female) | |

| 100% (113/113; P21 male) | 100% (101/101; P21 male) | |

| 100% (207/207; P120 male) | 91.7% (33/36; P120 male) | |

| M. pahari | 98.2 ± 0.8% | 87.5 ± 6.3% |

| 100% (72/72; P21 female) | 100% (83/83; P21 female) | |

| 94.6% (53/56; P21 female) | 82.4% (28/34; P21 female) | |

| 100% (28/28; P120 male) | 80% (8/10; P120 male) | |

| M. spretus | 90.3 ± 5.3% | 97.1 ± 1.6% |

| 81.8% (9/11; P120 female) | 94.7% (18/19; P120 female) | |

| 100% (102/102; P21 female) | 100% (58/58; P21 female) | |

| 89.2% (33/38; P21 female) | 96.5% (53/56; P21 female) | |

| PWD | 100% | 97.1 ± 2.0% |

| 100% (3/3; P120 female) | 90.0% (9/10; P120 female) | |

| 100% (12/12; P120 female) | 95.7% (22/23; P120 female) | |

| 100% (54/54; P21 female) | 100% (27/27; P120 female) | |

| 100% (48/48; P21 female) | ||

| 100% (22/22; P120 male) | ||

| Guinea Pig | 91.0 ± 5.7% | 85.9 ± 13.7% |

| 79.8% (281/352; P2 male) | 58.4% (156/267; P2 male) | |

| 98.3% (116/118; P2 male) | 99.2% (122/123; P2 male) | |

| 94.9% (148/156; P2 male) | 100% (100/100; P2 male) |

FXGs persist in mossy fibers in adult voles and Peromyscus

Our survey, along with our past studies of mice and rats (Akins et al., 2017), revealed that mossy fiber FXG abundance in adult animals varies dramatically between species. To better understand factors that might contribute to this variance, we investigated FXG expression within the order Rodentia, which comprises a vast number of species that vary in body size, behavior, and habitat and that together make up approximately 40% of all mammalian species (Kay & Hoekstra, 2008). Mice and rats both express hippocampal FXGs as juveniles but diverge in their adult expression patterns. We therefore examined both juveniles (P21) and young adults (P120) to capture FXG expression at each of the relevant developmental stages. We started with voles and California deer mice (Peromyscus) from the Cricetidae family, which diverged from the Muridae family containing mice and rats around 25 million years ago (Steppan, Adkins, & Anderson, 2004). We performed immunohistochemistry on hippocampal tissue sections for FXR2P and identified FXGs using standardized approaches as described in Methods. We quantified FXG abundance in dentate mossy fibers as well as in CA3 associational fibers (summarized in Table 2). FXGs were readily detected in these two regions in both species at P21 (Fig. 5). At P120, FXGs were evident in mossy fibers at levels comparable to or higher than those seen at P21, a pattern consistent with the developmental profile seen in rats. In contrast, FXG abundance decreased significantly in associational fibers, indicating that the developmental pattern of FXGs varies between the hippocampal circuits.

Table 2. Quantification and analysis of FXG abundance in rodents.

FXG abundance across brain regions in voles, Peromyscus, Mus pahari, Mus spretus, and Mus musculus musculus (PWD) was quantified and reported as FXG number per 100 μm2 (mean±SEM). Statistical analysis by Student’s T-test. Sample sizes are as follows: vole P21 n=4 (2 male, 2 female), P120 n=4 (2 male 2 female) for all regions; Peromyscus P21 n=2 (1 male, 1 female), P120 n=3 (3 female) for all regions; M. pahari P21 n=3 (3 female), P120 n=3 (2 male, 1 female) for all regions; M. spretus P21 n=3 (3 female), P120 n=3 (2 male, 1 female) for all regions; PWD P21 n=3 (2 male, 1 female) for all regions, P120 n=4 (1 male, 3 female) for mossy fibers, n=3 (1 male, 2 female) for associational fibers, n=2 (1 male 1 female) for frontal cortex and olfactory bulb.

| Vole | Peromyscus | M. pahari | M. spretus | PWD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mossy Fibers | P21 | 1.067±0.111 | 1.690±0.036 | 0.944±0.037 | 0.405±0.063 | 0.523±0.027 |

| P120 | 1.870±0.144 | 2.912±0.485 | 0.143±0.043 | 0.082±0.020 | 0.040±0.017 | |

| p-value | 0.0090 | 0.1462 | 0.0003 | 0.0080 | <0.0001 | |

| Associational Fibers | P21 | 0.232±0.051 | 0.504±0.018 | 0.525±0.004 | 0.218±0.033 | 0.272±0.047 |

| P120 | 0.047±0.014 | 0.022±0.002 | 0.022±0.004 | 0.052±0.006 | 0.061±0.019 | |

| p-value | 0.0097 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0080 | 0.0025 | |

| Frontal Cortex | P21 | 0.183±0.021 | 0.270±0.026 | 0.230±0.026 | 0.261±0.022 | 0.148±0.019 |

| P120 | 0.063±0.016 | 0.026±0.006 | 0.015±0.007 | 0.016±0.004 | 0.030±0.018 | |

| p-value | 0.0058 | 0.0013 | 0.0014 | 0.0004 | 0.0241 | |

| Olfactory Bulb | P21 | 1.034±0.073 | 1.046±0.108 | 3.957±0.366 | 2.556±0.017 | 1.960±0.211 |

| P120 | 0.409±0.038 | 2.301±0.351 | 3.229±0.347 | 1.994±0.246 | 3.767±0.401 | |

| p-value | 0.0004 | 0.0721 | 0.2226 | 0.0854 | 0.0209 | |

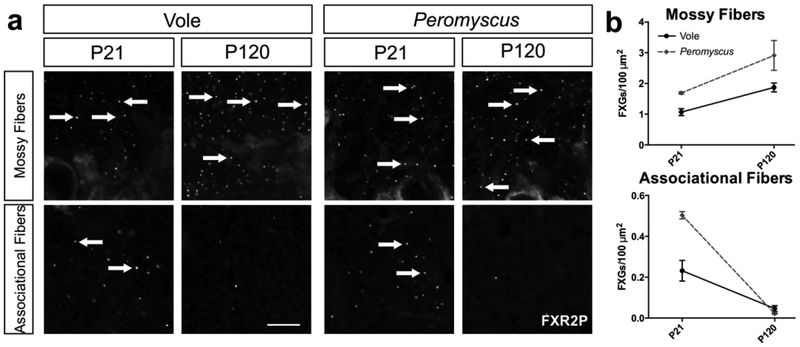

Figure 5. Mossy fiber FXGs persist into adulthood in some members of the Rodentia family.

(a) Confocal micrographs of immunostaining for FXR2P in hippocampal mossy and associational fibers. FXGs are abundant at P21 in vole and Peromyscus in both mossy and associational fibers, but while mossy fiber FXG abundance stays high through P120, it decreases drastically in associational fibers. (b) Quantification of FXG abundance in juvenile and adult vole and Peromyscus in mossy fibers and associational fibers. See Table 1 for FXG quantification and corresponding statistics. Vole P21 n=4 (2 male, 2 female), P120 n=4 (2 male 2 female); Peromyscus P21 n=2 (1 male, 1 female), P120 n=3 (3 female). Arrows indicate FXGs. Scale bar=10 μm.

Hippocampal FXGs are lost in adulthood in the Mus genus

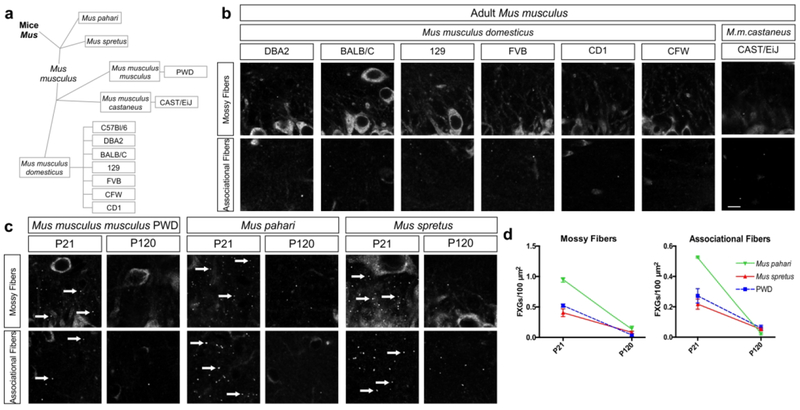

Our past findings showed that FXGs are rare in the adult hippocampus of C57Bl/6 mice (Akins et al., 2017; Christie et al., 2009) while our results here (Fig. 4) reveal they are also rare in adult PWD mice. The continued presence of FXGs in adult rat, vole, and Peromyscus hippocampus suggested that this difference may represent a species-specific divergence in FXG regulation that reflects differences in how the species live in the wild. However, lab mice have also been subjected to extensive controlled breeding for over a century, raising the possibility that the change in regulation may represent a quirk of selective breeding rather than revealing a difference in their native biology. To investigate these possibilities, we first asked whether FXGs are present in adult hippocampus in several additional M. musculus subspecies. We examined tissue from 6 additional strains of M. musculus domesticus (Fig. 6b) at ages ranging from P70 to P120, ages at which C57Bl/6 mice no longer express hippocampal FXGs (Christie et al., 2009). We found only rare hippocampal FXGs in adults of all of these strains, which included a mix of inbred and outbred strains (DBA2, BALB/C, 129, FVB, CFW, and CD1). Similarly, we saw very few hippocampal FXGs in adults of an additional M. musculus subspecies, M. musculus castaneus. The lack of FXGs in adult hippocampus thus appears to be a general feature of M. musculus that does not simply reflect lab adaptation.

Figure 6. Hippocampal FXGs are lost in adulthood in the Mus genus.

(a) Taxonomic key of examined members of the Mus genus. (b) FXGs were rare in hippocampus of adults (ranging from P60 to P150) of any examined Mus musculus domesticus strain or of Mus musculus castaneus. Confocal images of FXR2P immunostaining in CA3 stratum lucidum (mossy fibers) and CA3 stratum oriens (associational fibers) from: DBA2 (n = 2 males; age between P60-P90), BALB/C (n = 1 male, 1 female; P60-P90), 129 (n = 1 male, 1 female; P60-P90), FVB (n = 2 males; P60-P90), CD1 (n = 1 male, 1 female at P60-P90; 2 males at P150), CFW (n = 2 males at P60-P90; 2 males at P150), and CAST/EiJ (n= 2 males, 1 female at P150). (c) Confocal micrographs of immunostaining for FXR2P in hippocampal mossy fibers and associational fibers of M. pahari, M. spretus, and PWD. FXGs are abundant in both regions at P21 in Mus pahari, Mus spretus, and PWD but are nearly absent at P120. (d) Quantification of FXG abundance in juveniles and adults in Mus pahari, Mus spretus, and Mus musculus musculus (PWD) in both mossy fibers and associational fibers. While FXGs are abundant at P21 in both regions, they are nearly undetectable by P120 in all Mus species examined. See Table 2 for FXG quantification and corresponding statistics. M. pahari P21 n=3 (3 female), P120 n=3 (2 male, 1 female); M. spretus P21 n=3 (3 female), P120 n=3 (2 male, 1 female); PWD P21 n=3 (2 male, 1 female), P120 n=4 (1 male, 3 female) for mossy fibers and n=3 (1 male, 2 female) for associational fibers. Arrows indicate FXGs. Scale bar=10 μm.

We next asked whether other members of the Mus genus also exhibit a developmental decline in FXG abundance in the hippocampus. To complement our past studies of C57Bl/6 (M. musculus domesticus), we assessed the developmental pattern of FXG expression in PWD (M. musculus musculus) mice. We also extended our analyses to two related species within the Mus genus: M. pahari and M. spretus, which diverged from M. musculus approximately 6 million years ago (Thybert et al., 2018) and 2 million years ago (Galtier et al., 2004; Suzuki, Shimada, Terashima, Tsuchiya, & Aplin, 2004), respectively. We asked whether, similar to C57Bl/6, these mice had hippocampal FXGs as juveniles (P21) but not as adults (P120). Strikingly, the developmental pattern of hippocampal FXGs was consistent across these Mus species. FXGs were present in both mossy and associational fibers in juveniles but were rare in both circuits in the adults (Fig. 6c–d; Table 2). This pattern was unaffected by breeding history, as the examined Mus animals included inbred, outbred, and recently wild-derived species and strains (Table 3). Instead, downregulation of FXG abundance in adult hippocampus was conserved throughout the Mus genus.

Table 3. Characteristics of examined species.

Information collected from Animal Diversity Web, University of Michigan Museum of Zoology (Myers et al., 2018), except as noted: a: (MacMillen, 1964); b: (Asher et al., 2008); c: (Molur et al., 2005); d: (Smith & Xie, 2008); e: (Montoto et al., 2011); f: (Palomo, Justo, & Vargas, 2009); g: (Gray et al., 1998); h: (Mikesic & Drickamer, 1992). ‡ We were unable to find reports of wild prairie vole home range size in a manner that would allow comparison to the other species studied here or any reports of Mus pahari home range.

| Animal Species/Strain | Body Size (g) | Home Range (hectares) | Natural Habitat | Social Structure | Diet | Breeding History | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species with abundant FXGs in adult hippocampus | |||||||

| Human Homo sapiens | 54000–83000 | - | Ubiquitous | Diverse | Omnivore | - | |

| Opossum Monodelphis domestica | 80–155 | 0.8 | Tropical South America; ground or low-level vegetation | Solitary | Omnivore, mostly insects | Lab reared line established between 1978 and 1993 | |

| Armadillo Dasypus novemcinctus | 3600–7700 | 0.63–20.1 | Tropical and temperate Americas; forest/scrub brush, in burrows | Solitary | Omnivore, mostly insects | Wild-caught | |

| Tree shrew Tupaia belangeri | 50–270 | 0.81 | Tropical and subtropical southeast Asia; arboreal | Monogamous pairs | Insectivore, some fruit | Lab reared line first established ~1967 | |

| Prairie vole Microtus ochrogaster | 30–70 | n.d. ‡ | North American prairie; grass tunnels | Varies seasonally between solitary, mated pairs and small groups | Herbivore | Lab reared outbred line periodically refreshed with wild voles | |

| Deer mice Peromyscus californicusa | 33–55 | 0.15 | California chaparral, in burrows | Small family groups based around long-term monogamous pairs | Herbivore | Lab reared line established ~1985 | |

| Rat Rattus norvegicus Sprague Dawley & Long Evans | 200–500 | 0.2 | Native to northern China, currently ubiquitous; in burrows, preferably in riparian areas | Large groups | Omnivore | Lab reared outbred line first established ~1925 | |

| Species with scarce FXGs in adult hippocampus | |||||||

| Hartley Guinea Pig Cavia porcellus | 700–1100 | 0.03–0.07 (for the related C. aperea)b | Domesticated ~7000 years ago from an extinct South American ancestor | Gregarious groups with male social hierarchies | Herbivore | Lab reared outbred line, last wild ancestor ~5000 BC | |

| Mouse (Mus) | Gairdner’s shrewmouse M. paharic,d | ~30e | n.d.‡ | Southeast Asia; montane, semi-arboreal, nests in dry grass | - | Omnivore | Lab reared line established 1995 |

| Algerian mouse M. spretusf | 15–19e | ~0.03g | Mediterranean grasslands; open terrain | Solitary | Omnivore | Lab reared inbred line established in 1978 | |

| M. musculus castaneus (CAST/EiJ) | 20–45 | 0.02–0.05h | Southern and southeastern Asia | Small family groups | Omnivore | Lab reared inbred line established in 1971 | |

| M. musculus musculus (PWD) | Eastern Europe and northern Asia | Lab reared inbred line established in 1972 | |||||

| M. musculus domesticus (C57Bl/6, DBA2, Balb/C, 129, FVB, CFW, CD-1) | Ubiquitous; fields and forests, close associations with humans | Lab reared as 5 inbred and 2 outbred lines that originated between 1913 and 1935 | |||||

Frontal cortex and olfactory bulb FXG developmental patterns are consistent across species

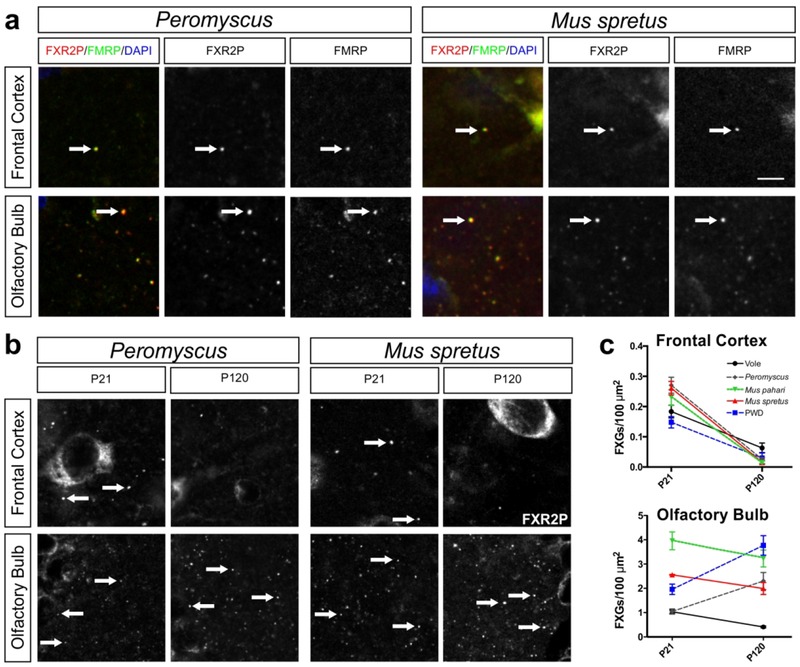

Previous findings have indicated that, in contrast to the hippocampus, the FXG developmental profile is similar between mice and rats in frontal cortex (where both species exhibit a developmental decrease in FXG abundance) and olfactory bulb (where FXGs are expressed across the lifespan) (Akins et al., 2017). To determine if these observed patterns are consistent across species, we quantified FXG abundance in frontal cortex and olfactory bulb in vole, Peromyscus, M. pahari, M. spretus, and PWD mice at P21 and P120 (Fig. 7). FXGs were found in these circuits in all species examined. Consistent with the protein composition seen in past studies in mice, a large majority of granules in both brain regions contained both FXR2P and FMRP (Table 4). In all species FXG abundance declined significantly in the frontal cortex between P21 and P120.

Figure 7. Frontal cortex and olfactory bulb FXG developmental pattern throughout the Rodentia family.

(a) Confocal micrographs of coimmunostaining of FXGs, indicated by FXR2P (red) with FMRP (green) in frontal cortex and olfactory bulb of P120 Peromyscus and Mus spretus. FMRP colocalized with FXGs in both regions at P21 and P120 in all species examined (vole, PWD, Peromyscus, Mus pahari, and Mus spretus, data not shown). DAPI (blue) used as a nuclear stain. (b) Confocal micrographs of immunostaining for FXR2P in frontal cortex and olfactory bulb of Peromyscus and Mus spretus at P21 and P120. Arrows indicate FXGs. (c) Quantification of frontal cortex and olfactory bulb FXG abundance in Peromyscus, vole, Mus pahari, M. spretus, and PWD at P21 and P120. In frontal cortex of all species examined, FXG abundance declines drastically by P120 compared to P21. In olfactory bulb, FXG abundance did not change with age in Peromyscus, M. pahari, or M. spretus, but was lower in adults than juveniles in voles, and higher in adults than juveniles in PWD. See Table 1 for FXG quantification and statistics values. Vole P21 n=4 (2 male, 2 female), P120 n=4 (2 male 2 female); Peromyscus P21 n=2 (1 male, 1 female), P120 n=3 (3 female); M. pahari P21 n=3 (3 female), P120 n=3 (2 male, 1 female); M. spretus P21 n=3 (3 female), P120 n=3 (2 male, 1 female); PWD P21 n=3 (2 male, 1 female), P120 n=2 (1 male 1 female). Arrows indicate FXGs. Scale bar=6 μm (a), 10 μm (b).

Table 4. Quantification of FMRP-containing FXGs in frontal cortex and olfactory bulb across species.

FXGs were identified in cortical and olfactory bulb axons of the examined species based on FXR2P immunoreactivity. The percentage and absolute number of these FXGs that also contained FMRP is indicated. For each animal (age and sex as indicated) the number of FXGs represents the summed total across 1–4 sections. Mean (± standard error as appropriate) is indicated for each region/species.

| Frontal Cortex | Olfactory Bulb | |

|---|---|---|

| Vole | 98.2 ± 1.8% | 96.9 ± 1.7% |

| 100% (22/22; P21 female) | 100% (46/46; P21 female) | |

| 94.7% (18/19; P120 female) | 94.1% (64/68; P120 female) | |

| 100% (47/47; P120 female) | 96.7% (29/30; P120 female) | |

| Peromyscus | 98.2 ± 1.1% | 99.8 ± 0.2% |

| 100% (41/41; P21 female) | 100% (42/42; P21 female) | |

| 98.2% (55/56; P21 male) | 100% (75/75; P21 male) | |

| 96.3% (26/27; P120 male) | 99.2% (137/138; P120 male) | |

| M. pahari | 100% | 99.3 ± 0.7% |

| 100% (55/55; P21 female) | 100% (70/70; P21 female) | |

| 100% (60/60; P120 female) | 100% (93/93; P120 male) | |

| 97.8% (44/45; P120 male) | ||

| M. spretus | 100% | 96.8 ± 1.6% |

| 100% (7/7; P120 female) | 100% (53/53; P120 female) | |

| 100% (70/70; P21 female) | 95.7% (110/115; P21 female) | |

| 94.6% (53/56: P21 female) | ||

| PWD | 100% | 90.5 ± 7.8% |

| 100% (71/71; P21 female) | 98.3% (113/115; P21 female) | |

| 100% (7/7; P120 female) | 82.7% (105/127; P120 male) | |

| 100% (3/3; P120 male) | ||

| Guinea Pig | 98.0 ± 1.2% | 95.1% (39/41; P2 male) |

| 98.4% (120/122; P2 male) | ||

| 95.7% (68/71; P2 male) | ||

| 100% (39/39; P2 male) |

Although FXG abundance in the olfactory bulbs of all species remained high at both ages, we did observe small but significant changes in most species. FXG abundance remained steady in Peromyscus, M. pahari, and M. spretus but decreased with age in voles and increased with age in PWD mice (Fig. 7b–c, Table 2). Both rats and C57Bl/6 mice exhibit a developmental increase in olfactory bulb FXG abundance up to a peak that is then followed by a decrease to the levels seen in adults (Akins et al., 2017; Christie et al., 2009). The developmental timing of these peaks differs – for rats it occurs around P60 while for C57Bl/6 mice it occurs about P30. The species-dependent differences in FXG abundance seen in the present study may reflect similar variability in the timing of peak FXG abundance. Taken together, our findings from hippocampus, frontal cortex, and olfactory bulb indicate that the developmental profile of FXG expression in forebrain circuits is largely conserved across species with the single exception of dentate mossy fibers.

Species with small home range sizes lack mossy fiber FXGs in adulthood

The divergence in adult hippocampal FXG abundance in the Mus lineage raises the possibility that these animals were subjected to different environmental constraints that led to a diminished requirement for FXG function in the adult hippocampus. We examined potentially relevant factors including body size, home range size, natural habitat, social structure, diet, breeding history, and housing conditions (Table 3). Among these, Mus were distinguished by their particularly small home range but also were among the smallest in terms of body size.

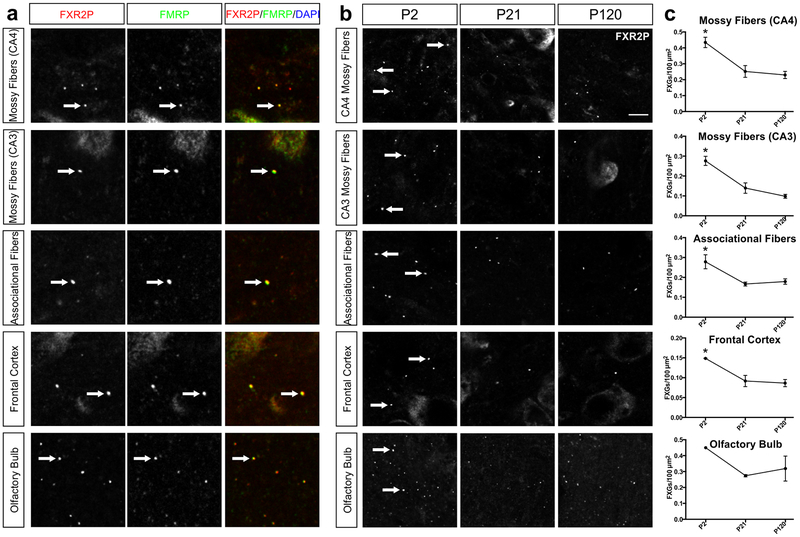

To investigate the potential contribution of these factors, we examined FXG expression in guinea pigs, who are much larger than mice but occupy similarly small home ranges (Asher, de Oliveira, & Sachser, 2004; Asher et al., 2008). However, in contrast to the other, altricial rodent species examined here, guinea pigs are precocial. Our past studies in mice revealed that FXGs are rare until approximately P15, coinciding with eye opening and increased exploration (Christie et al., 2009). Because guinea pigs can fully explore their environment essentially immediately after birth, we hypothesized that they might express FXGs earlier than mice. We therefore investigated FXG expression in P2 neonates in addition to P21 juveniles and P120 adults. We observed FXGs in P2 animals in axons of all examined brain regions including mossy fibers, CA3 associational fibers, olfactory sensory neuron axons in olfactory bulb, and axons innervating frontal cortex (Fig. 8; Table 5). Because guinea pig hippocampus is more elaborated than that in other rodents with defined CA4 and CA3 regions, we quantified FXGs in dentate mossy fibers in both of these regions. In all five regions, abundance declined significantly from P2 to P21, attaining levels consistent with those seen at P120. Further, as in all examined species, FXR2P and FMRP were components of FXGs in all of these brain regions (Tables 2, 4). The decrease in mossy fiber FXGs in guinea pigs differs from the developmental increase seen in other species and instead echoes, although less dramatically, the developmental decrease seen in Mus species.

Figure 8. FMRP-containing FXGs are abundant across the brain in neonatal guinea pigs and decline with age.

(a) Confocal micrographs of coimmunostaining for FXGs, indicated by FXR2P (red) and FMRP (green) in mossy fibers, associational fibers, frontal cortex, and olfactory bulb of P120 guinea pig. FMRP colocalized with FXGs in all four regions at P120 as well as P2 and P21 (data not shown). DAPI (blue) used as a nuclear stain. Arrows indicate FXGs. (b) Confocal micrographs of immunostaining for FXGs, indicated by FXR2P, in mossy fibers in the CA3 and CA4 regions, associational fibers, frontal cortex, and olfactory bulb in guinea pig at P2, P21, and P120. (c) Quantification of FXG abundance. FXG abundance decreased significantly in all hippocampal regions and frontal cortex between the neonate (P2) and juvenile (P21), then remained stable into adulthood (P120). See Table 5 for FXG quantification and statistics values. n=3 males for all regions except olfactory bulb where P2 n=1, P21 and P120 n=2. Scale bar=6 μm (a), 10 μm (b).

Table 5. Quantification and analysis of FXG abundance in guinea pigs.

FXG abundance across brain regions in guinea pigs was quantified and reported as number of FXGs per 100 μm2 (mean±SEM). Statistical analysis by ANOVA with multiple comparisons; n=3 except olfactory bulb where n=1 at P2; n=2 at P21 and P120; all guinea pigs examined were male. There was no statistical difference between P21 and P120 for any region.

| Mossy fibers (CA4) (ANOVA p=0.0068) | Mossy fibers (CA3) (ANOVA p=0.0023) | Associational fibers (ANOVA p=0.0237) | Frontal Cortex (ANOVA p=0.0070) | Olfactory Bulb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2 | 0.434±0.032 | 0.276±0.023 | 0.279±0.035 | 0.149±0.001 | 0.450 |

| P21 | 0.252±0.037 (p=0.0124 vs P2) | 0.139±0.026 (p=0.0073 vs P2) | 0.167±0.010 (p=0.0373 vs P2) | 0.092±0.014 (p=0.0119 vs P2) | 0.274±0.007 |

| P120 | 0.230±0.022 (p=0.0108 vs P2) | 0.098±0.010 (p=0.0029 vs P2) | 0.178±0.014 (p=0.0402 vs P2) | 0.086±0.009 (p=0.0118 vs P2) | 0.319±0.079 |

Discussion

In this study, we investigated FXG expression across mammalian species as a means to address whether these granules are likely to play fundamental, conserved roles. FXGs were found in the brains of every examined species, including both placental and nonplacental mammals (Fig. 9). Many aspects of these granules were conserved including the RNA binding proteins they comprise, the circuits in which they are found, and the developmental timing of FXG expression in olfactory bulb and neocortex. Interestingly, one aspect that diverged among species was the developmental window in which FXGs were found in hippocampus, with FXGs found in the adult hippocampus of most but not all mammals. Investigation of this divergence within rodents suggested that the species that lose FXG expression in the adult hippocampus may be those that occupy small home ranges in the wild. Together, these findings indicate that FXGs are broadly conserved in the mammalian brain and that FXG-regulated translation likely plays important roles in controlling the neuronal proteome.

Figure 9. Summary of FXG expression in mammals.

Together with past analyses of FXG expression in M. musculus, rats and humans (Christie et al., 2009; Akins et al., 2017), our findings show that FXGs are present in the brains of all examined mammalian species across ~160 million years (MYrs) of divergent evolution, including in olfactory bulb (OB), frontal cortex (Cortex), and hippocampal mossy fibers (Hipp MF). The spatiotemporal pattern of their expression is largely conserved, with most species having FXGs in the adult hippocampus. In contrast, guinea pigs and members of the Mus genus lack adult hippocampal FXGs (indicated by dashed lines). The presence of adult hippocampal FXGs corresponds with a large natural home range size, but cannot be explained by body size, rearing conditions, or evolutionary relationships. Phylogenetic relationships based on the Open Tree of Life (Hinchliff et al., 2015). See also Fig. 1 and Table 3.

Local protein synthesis following transport of mRNAs to particular subcellular locations is a fundamental mechanism for controlling the spatial distribution of proteins within cells that occurs not only in eukaryotes but also in bacteria (Buxbaum et al., 2015; Jung, Gkogkas, Sonenberg, & Holt, 2014; Martin & Ephrussi, 2009; Nevo-Dinur et al., 2011; Vazquez-Pianzola & Suter, 2012). The RNPs and their constituent RNA binding proteins that are associated with the transport and translational control of localized mRNAs are specific to particular lineages with, for example, some found only in yeast or in animals (Claußen & Suter, 2005; Heym & Niessing, 2012; Vazquez-Pianzola & Suter, 2012). Within animals, the FXR protein family is widely conserved and consistently controls the translation of localized mRNAs within neurons (Bassell & Warren, 2008). Among the FXR protein-containing complexes, FXGs are unique with regard to their neuron type specificity and subcellular distribution solely within axons. The findings presented here reveal that this specificity is consistent across a remarkably diverse collection of mammalian species indicating that the mechanisms that govern FXG formation and localization are highly conserved. Moreover, the widespread conservation of these axonal RNPs suggests that local axonal protein synthesis, a phenomenon that has only recently been widely studied, is an ancient, conserved mechanism for regulating the axonal proteome in the mammalian brain.

Several lines of evidence suggest that FXG-regulated translation modulates experience-dependent synaptogenesis. FXGs are most abundant in axons that are undergoing experience-dependent synapse formation and elimination. For example, in adult animals FXGs are consistently seen across all species in olfactory sensory neuron axons in the olfactory bulb (Akins et al., 2017; Christie et al., 2009). These neurons are generated throughout life and exhibit a remarkable degree of experience-dependent structural plasticity during initial circuit integration that continues long after the axons have formed synapses and reached maturity (Cheetham, Park, & Belluscio, 2016). Lesion studies of the olfactory neurons showed that FXGs are most abundant as newly formed neurons are forming synapses (Christie et al., 2009). Interestingly, the developmental onset of FXG expression further points toward a correlation with circuit refinement. In mice and rats, FXGs are rare or absent at birth and don’t appear until approximately two weeks of age (Christie et al., 2009). This timing corresponds to a period of intense sensory exploration of the world since it occurs during the time when visual and auditory information first impinge on the CNS, leading to experience-dependent circuit refinement (Barkat, Polley, & Hensch, 2011; Hensch, 2004, 2005). In contrast to rats and mice, guinea pigs are precocial and therefore receive and process sensory information and eat solid food shortly after birth (Künkele & Trillmich, 1997). Notably, FXGs were found in brains from neonatal guinea pigs, further supporting a correlation between FXG onset and initial sensory experience. Directly manipulating sensory experience (e.g., olfactory deprivation by naris occlusion or visual deprivation by dark rearing) and measuring the effect on FXG abundance would test this possibility. Moreover, this correlation further suggests the possibility that the number and specific subaxonal localization of FXGs in an individual axon is dependent on the activity of that neuron. Consistent with this, the levels and localization of dendritic FMRP, mRNA, and ribosomes are controlled by sensory experience and neuronal activity in order to meet the unique information processing demands placed on individual neurons (Dictenberg, Swanger, Antar, Singer, & Bassell, 2008; Gabel et al., 2004; Kim, Kim, Kim, & Schuman, 2005; Wang et al., 2014). Together, these findings suggest that FXGs play similar, conserved roles in guiding experience-dependent synaptogenesis by axons.

An open question is the identity of the molecular cues that govern the exquisitely specific pattern of FXG localization to axons, even though the FXR proteins themselves are expressed nearly ubiquitously in all neuron types across the nervous system (Christie et al., 2009; Zorio, Jackson, Liu, Rubel, & Wang, 2017). The localization and function of FXGs within axons of individual neurons is likely controlled by extrinsic cues since at least some neuron types exhibit selective localization of FXGs to particular axon branches. For example, FXGs are found in the recurrent axons of CA3 pyramidal neurons that innervate CA3 but not in the Schaffer collaterals that innervate CA1 (Akins et al., 2012). Glutamate and neurotrophins are leading candidates to govern FXG localization, since these signals control the localization and function of other axonal RNPs (Hsu et al., 2015; Ji & Jaffrey, 2012; Willis et al., 2005; Yao, Sasaki, Wen, Bassell, & Zheng, 2006; X. Zhang & Poo, 2002). However, to our knowledge, none of these cues have spatiotemporal distributions that can explain the FXG expression pattern, particularly the interspecies differences. For example, differing neurotrophin levels are unlikely to account for species-dependent FXG expression patterns since these cues exhibit equivalent developmental expression profiles in rat and mouse hippocampus (Katoh-Semba, Semba, Takeuchi, & Kato, 1998). The formation and localization of FXGs could be driven by other, as yet unidentified, extrinsic molecular cues. Alternatively, FXG-containing axons could express a combination of receptor complexes and axonal transport machinery that render them uniquely sensitive to widely expressed cues such as neurotrophins. Together, our findings suggest that the localization and function of FXGs, as well as their associated ribosomes and mRNAs, are controlled by novel regulatory mechanisms.

In addition to first appearing as circuits are forming, FXGs are developmentally downregulated in most brain regions, including cerebellum and neocortex, after robust experience-dependent circuit refinement has concluded (Akins et al., 2017; Christie et al., 2009). In contrast, FXGs persist into adulthood in both olfactory bulb and hippocampus in most species. While lesion studies showed a link between neurogenesis and FXG expression in the olfactory bulb (Christie et al., 2009), FXG expression in the hippocampus is independent of neurogenesis (Akins et al., 2017), indicating an ongoing role for FXG-regulated translation in mature axons in this circuit. Interestingly, adult FXG expression was lost in the Mus lineage sometime after it diverged from the Rattus lineage, even though expression in the juveniles is similar between mice and rats. This deviation could merely reflect random genetic variation, but it also raises the possibility that the organismal roles that hippocampal FXGs support are less prominent in adult mice than in adults of other mammalian species. A survey of factors that may have led to this deviation pointed towards the comparatively small home range occupied by mice in the wild, suggesting that ecological factors may contribute to whether FXGs persist or are absent from adult hippocampus of particular species. Consistent with this idea, guinea pigs, whose wild relatives also occupy very small home ranges and apparently are not reliant on spatial strategies when navigating in lab settings (Lewejohann, Pickel, Sachser, & Kaiser, 2010), were the only examined species outside the Mus genus that exhibited a developmental decline in FXG expression in hippocampal mossy fibers. The relative paucity of FXGs in adult mice and guinea pigs may reflect the smaller territories inhabited by individuals of these species. This interpretation is consistent with the hypothesis that the size of an individual’s home range along with the strategies needed to find food and navigate social interactions within that range are important evolutionary influences on hippocampal size (Konefal, Elliot, & Crespi, 2013; Murray, Wise, & Graham, 2018; Sherry, Jacobs, & Gaulin, 1992). As discussed above, FXGs may modulate the formation and modification of synapses (Akins et al., 2017; Christie et al., 2009; Chyung et al., 2018). Sustained expression of FXGs in the adult hippocampus may support the continuous circuit rewiring that occurs as animals navigate a large and changing world.

Axonal FMRP functions are varied and include regulation of ion channel function and localization as well as regulation of protein synthesis during axon outgrowth and synapse formation (Deng et al., 2013; Ferron, Nieto-Rostro, Cassidy, & Dolphin, 2014; Li, Bassell, & Sasaki, 2009; Zimmer, Doll, Garcia, & Akins, 2017). Loss of these functions likely contributes to the cognitive and neurological symptoms seen in FXS patients. In particular, the presence of FXGs, and their associated translational machinery, in the adult human hippocampus points towards a role for FMRP-regulated local protein synthesis in this circuit in humans. The majority of our mechanistic understanding of FMRP and how its loss impacts synaptic function come from the study of mouse models of Fragile X. In terms of presynaptic FMRP in mature hippocampal circuits, however, mice are not representative of the vast majority of mammalian species including humans. Elucidating how FXG-associated presynaptic FMRP contributes to adult circuit function, and how its loss may impact adult Fragile X patients, therefore requires studies in species outside the Mus genus. For example, Peromyscus and rats both engage in complex social behaviors and provide ideal models for investigating the relationship between such behaviors and the regulation and function of FXGs. Moreover, Fmr1 null rats (Hamilton et al., 2014) provide a basis for understanding FMRP control of FXG functions in adult mammals in general as well as a more clinically relevant model than Fmr1 null mice for the investigation of FXG dysregulation in human FXS patients.

Acknowledgements.

We are grateful to colleagues who donated animal tissue: Dr. Elizabeth Becker (St. Joseph’s University; Peromyscus), Dr. Bruce Cushing (The University of Texas at El Paso; vole), Dr. Jeffery Padberg (University of Central Arkansas; armadillo), and Dr. Leah Krubitzer (University of California, Davis; opossum and tree shrew). We are also grateful to Dr. Dylan Cooke for helping arrange tissue donations and for critical reading of the manuscript, to Dr. Sean O’Donnell for critical reading of the manuscript, and to Duy Le, Sachi Desai, Anshul Ramanathan, and Eric Gebski for technical assistance. Work in the Akins lab was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R00 MH090237. The opossum colony at UC Davis was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 EY022987 and Grant # 220020516 from the McDonnell Foundation.

Footnotes

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Akins MR, Berk-Rauch HE, Kwan KY, Mitchell ME, Shepard KA, Korsak LIT, … Fallon JR (2017). Axonal ribosomes and mRNAs associate with fragile X granules in adult rodent and human brains. Human Molecular Genetics, 26(1), 192–209. 10.1093/hmg/ddw381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akins MR, LeBlanc HF, Stackpole EE, Chyung E, & Fallon JR (2012). Systematic mapping of fragile X granules in the mouse brain reveals a potential role for presynaptic FMRP in sensorimotor functions. The Journal of Comparative Neurology, 520(16), 3687–3706. 10.1002/cne.23123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher M, de Oliveira ES, & Sachser N (2004). Social System and Spatial Organization of Wild Guinea Pigs (Cavia aperea) in a Natural Population. Journal of Mammalogy, 85(4), 788–796. 10.1644/BNS-012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asher M, Lippmann T, Epplen JT, Kraus C, Trillmich F, & Sachser N (2008). Large males dominate: Ecology, social organization, and mating system of wild cavies, the ancestors of the guinea pig. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 62(9), 1509–1521. 10.1007/s00265-008-0580-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barkat TR, Polley DB, & Hensch TK (2011). A critical period for auditory thalamocortical connectivity. Nature Neuroscience, 14(9), 1189–1194. 10.1038/nn.2882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ, & Warren ST (2008). Fragile X Syndrome: Loss of Local mRNA Regulation Alters Synaptic Development and Function. Neuron, 60(2), 201–214. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biever A, Donlin-Asp PG, & Schuman EM (2019). Local translation in neuronal processes. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 57, 141–148. 10.1016/j.conb.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxbaum AR, Haimovich G, & Singer RH (2015). In the right place at the right time: Visualizing and understanding mRNA localization. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 16(2), 95–109. 10.1038/nrm3918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham CEJ, Park U, & Belluscio L (2016). Rapid and continuous activity-dependent plasticity of olfactory sensory input. Nature Communications, 7, 10729 10.1038/ncomms10729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie SB, Akins MR, Schwob JE, & Fallon JR (2009). The FXG: A Presynaptic Fragile X Granule Expressed in a Subset of Developing Brain Circuits. J. Neurosci, 29(5), 1514–1524. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3937-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyung E, LeBlanc HF, Fallon JR, & Akins MR (2018). Fragile X granules are a family of axonal ribonucleoprotein particles with circuit-dependent protein composition and mRNA cargos. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 526(1), 96–108. 10.1002/cne.24321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claußen M, & Suter B (2005). BicD-dependent localization processes: From Drosophilia development to human cell biology. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger, 187(5), 539–553. 10.1016/j.aanat.2005.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC, Fraser CE, Mostovetsky O, & Darnell RB (2009). Discrimination of common and unique RNA-binding activities among Fragile X mental retardation protein paralogs. Human Molecular Genetics, 18(17), 3164–3177. 10.1093/hmg/ddp255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC, & Klann E (2013). The translation of translational control by FMRP: Therapeutic targets for FXS. Nature Neuroscience, 16(11), 1530–1536. 10.1038/nn.3379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng P-Y, Rotman Z, Blundon JA, Cho Y, Cui J, Cavalli V, … Klyachko VA (2013). FMRP Regulates Neurotransmitter Release and Synaptic Information Transmission by Modulating Action Potential Duration via BK Channels. Neuron, 77(4), 696–711. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dictenberg JB, Swanger SA, Antar LN, Singer RH, & Bassell GJ (2008). A Direct Role for FMRP in Activity-Dependent Dendritic mRNA Transport Links Filopodial-Spine Morphogenesis to Fragile X Syndrome. Developmental Cell, 14(6), 926–939. 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edbauer D, Neilson JR, Foster KA, Wang C-F, Seeburg DP, Batterton MN, … Sheng M (2010). Regulation of Synaptic Structure and Function by FMRP-Associated MicroRNAs miR-125b and miR-132. Neuron, 65(3), 373–384. 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron L, Nieto-Rostro M, Cassidy JS, & Dolphin AC (2014). Fragile X mental retardation protein controls synaptic vesicle exocytosis by modulating N-type calcium channel density. Nature Communications, 5 10.1038/ncomms4628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabel LA, Won S, Kawai H, McKinney M, Tartakoff AM, & Fallon JR (2004). Visual Experience Regulates Transient Expression and Dendritic Localization of Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein. J. Neurosci, 24(47), 10579–10583. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2185-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galtier N, Bonhomme F, Moulia C, Belkhir K, Caminade P, Desmarais E, … Boursot P (2004). Mouse biodiversity in the genomic era. Cytogenetic and Genome Research, 105(2–4), 385–394. 10.1159/000078211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray SJ, Hurst JL, Stidworthy R, Smith J, Preston R, & MacDougall R (1998). Microhabitat and spatial dispersion of the grassland mouse (Mus spretus Lataste). Journal of Zoology, 246(3), 299–308. 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1998.tb00160.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gregorová S, & Forejt J (2000). PWD/Ph and PWK/Ph inbred mouse strains of Mus m. Musculus subspecies—A valuable resource of phenotypic variations and genomic polymorphisms. Folia Biologica, 46(1), 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton SM, Green JR, Veeraragavan S, Yuva L, McCoy A, Wu Y, … Paylor R (2014). Fmr1 and Nlgn3 knockout rats: Novel tools for investigating autism spectrum disorders. Behavioral Neuroscience, 128(2), 103–109. 10.1037/a0035988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK (2004). Critical period regulation. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 27, 549–579. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK (2005). Critical period plasticity in local cortical circuits. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 6(11), 877–888. 10.1038/nrn1787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heym RG, & Niessing D (2012). Principles of mRNA transport in yeast. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 69(11), 1843–1853. 10.1007/s00018-011-0902-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchliff CE, Smith SA, Allman JF, Burleigh JG, Chaudhary R, Coghill LM, … Cranston KA (2015). Synthesis of phylogeny and taxonomy into a comprehensive tree of life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(41), 12764–12769. 10.1073/pnas.1423041112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu W-L, Chung H-W, Wu C-Y, Wu H-I, Lee Y-T, Chen E-C, … Chang Y-C (2015). Glutamate Stimulates Local Protein Synthesis in the Axons of Rat Cortical Neurons by Activating α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic Acid (AMPA) Receptors and Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 290(34), 20748–20760. 10.1074/jbc.M115.638023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji S-J, & Jaffrey SR (2012). Intra-axonal Translation of SMAD1/5/8 Mediates Retrograde Regulation of Trigeminal Ganglia Subtype Specification. Neuron, 74(1), 95–107. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, Gkogkas CG, Sonenberg N, & Holt CE (2014). Remote Control of Gene Function by Local Translation. Cell, 157(1), 26–40. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh-Semba R, Semba R, Takeuchi IK, & Kato K (1998). Age-related changes in levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in selected brain regions of rats, normal mice and senescence-accelerated mice: A comparison to those of nerve growth factor and neurotrophin-3. Neuroscience Research, 31(3), 227–234. 10.1016/S0168-0102(98)00040-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay EH, & Hoekstra HE (2008). Rodents. Current Biology, 18(10), R406–R410. 10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Kim Y-B, Kim E-G, & Schuman E (2005). Measurement of dendritic mRNA transport using ribosomal markers. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 328(4), 895–900. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konefal S, Elliot MG, & Crespi B (2013). The adaptive significance of adult neurogenesis: An integrative approach. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, 7 10.3389/fnana.2013.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korsak LIT, Mitchell ME, Shepard KA, & Akins MR (2016). Regulation of Neuronal Gene Expression by Local Axonal Translation. Current Genetic Medicine Reports, 4(1), 16–25. 10.1007/s40142-016-0085-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Künkele J, & Trillmich F (1997). Are Precocial Young Cheaper? Lactation Energetics in the Guinea Pig. Physiological Zoology, 70(5), 589–596. 10.1086/515863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewejohann L, Pickel T, Sachser N, & Kaiser S (2010). Wild genius - domestic fool? Spatial learning abilities of wild and domestic guinea pigs. Frontiers in Zoology, 7(1), 9 10.1186/1742-9994-7-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Bassell G. j, & Sasaki Y (2009). Fragile X mental retardation protein is involved in protein synthesis-dependent collapse of growth cones induced by Semaphorin-3A. Frontiers in Neural Circuits, 3, 11 10.3389/neuro.04.011.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillen RE (1964). Population ecology, water relations, and social behavior of a Southern California semi-desert rodent fauna (Vol. 71). University of California Publications Zoology. [Google Scholar]

- Martin KC, & Ephrussi A (2009). mRNA Localization: Gene Expression in the Spatial Dimension. Cell, 136(4), 719–730. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikesic DG, & Drickamer LC (1992). Factors Affecting Home-Range Size in House Mice (Mus musculus domesticus) Living in Outdoor Enclosures. The American Midland Naturalist, 127(1), 31–40. 10.2307/2426319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molur S, Srinivasulu C, Srinivasulu B, Walker S, Nameer PO, & Ravikumar L (2005). Status of nonvolant small mammals: Conservation Assessment & Management Plan (C.A.M.P.) Workshop Report (No. 23; p. 618). Coimbatore, India: Zoo Outreach Organisation/CBSG-South Asia. [Google Scholar]

- Montagutelli X, Serikawa T, & Guénet JL (1991). PCR-analyzed microsatellites: Data concerning laboratory and wild-derived mouse inbred strains. Mammalian Genome: Official Journal of the International Mammalian Genome Society, 1(4), 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoto LG, Magaña C, Tourmente M, Martín-Coello J, Crespo C, Luque-Larena JJ, … Roldan ERS (2011). Sperm Competition, Sperm Numbers and Sperm Quality in Muroid Rodents. PLoS One; San Francisco, 6(3), e18173 http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy2.library.drexel.edu/10.1371/journal.pone.0018173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EA, Wise SP, & Graham KS (2018). Representational specializations of the hippocampus in phylogenetic perspective. Neuroscience Letters, 680, 4–12. 10.1016/j.neulet.2017.04.065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers P, Espinosa R, Parr CS, Jones T, Hammond GS, & Dewey TA (2018). The Animal Diversity Web (online). Retrieved November 4, 2018, from Animal Diversity Web website: https://animaldiversity.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Nevo-Dinur K, Nussbaum-Shochat A, Ben-Yehuda S, & Amster-Choder O (2011). Translation-Independent Localization of mRNA in E. coli. Science, 331(6020), 1081–1084. 10.1126/science.1195691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomo LJ, Justo ER, & Vargas JM (2009). Mus spretus (Rodentia: Muridae). Mammalian Species, (840), 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Scarnati MS, Kataria R, Biswas M, & Paradiso KG (2018). Active presynaptic ribosomes in the mammalian brain, and altered transmitter release after protein synthesis inhibition. ELife, 7, e36697 10.7554/eLife.36697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherry DF, Jacobs LF, & Gaulin SJC (1992). Spatial memory and adaptive specialization of the hippocampus. Trends in Neurosciences, 15(8), 298–303. 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90080-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AT, & Xie Y (2008). A Guide to the Mammals of China. Retrieved from https://press.princeton.edu/titles/8631.html [Google Scholar]

- Steppan S, Adkins R, & Anderson J (2004). Phylogeny and divergence-date estimates of rapid radiations in muroid rodents based on multiple nuclear genes. Systematic Biology, 53(4), 533–553. 10.1080/10635150490468701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Shimada T, Terashima M, Tsuchiya K, & Aplin K (2004). Temporal, spatial, and ecological modes of evolution of Eurasian Mus based on mitochondrial and nuclear gene sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 33(3), 626–646. 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thybert D, Roller M, Navarro FCP, Fiddes I, Streeter I, Feig C, … Flicek P (2018). Repeat associated mechanisms of genome evolution and function revealed by the Mus caroli and Mus pahari genomes. Genome Research, 28(4), 448–459. 10.1101/gr.234096.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez-Pianzola P, & Suter B (2012). Conservation of the RNA Transport Machineries and Their Coupling to Translation Control across Eukaryotes. International Journal of Genomics. 10.1155/2012/287852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Sakano H, Beebe K, Brown MR, Laat R. de, Bothwell M, … Rubel EW (2014). Intense and specialized dendritic localization of the fragile X mental retardation protein in binaural brainstem neurons: A comparative study in the alligator, chicken, gerbil, and human. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 522(9), 2107–2128. 10.1002/cne.23520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis D, Li KW, Zheng J-Q, Chang JH, Smit A, Kelly T, … Twiss JL (2005). Differential Transport and Local Translation of Cytoskeletal, Injury-Response, and Neurodegeneration Protein mRNAs in Axons. J. Neurosci, 25(4), 778–791. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4235-04.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J, Sasaki Y, Wen Z, Bassell GJ, & Zheng JQ (2006). An essential role for β-actin mRNA localization and translation in Ca2+-dependent growth cone guidance. Nature Neuroscience, 9(10), 1265–1273. 10.1038/nn1773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Younts TJ, Monday HR, Dudok B, Klein ME, Jordan BA, Katona I, & Castillo PE (2016). Presynaptic Protein Synthesis Is Required for Long-Term Plasticity of GABA Release. Neuron, 92(2), 479–492. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zang JB, Nosyreva ED, Spencer CM, Volk LJ, Musunuru K, Zhong R, … Darnell RB (2009). A Mouse Model of the Human Fragile X Syndrome I304N Mutation. PLoS Genet, 5(12), e1000758 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, & Poo M (2002). Localized Synaptic Potentiation by BDNF Requires Local Protein Synthesis in the Developing Axon. Neuron, 36(4), 675–688. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01023-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, O’Connor JP, Siomi MC, Srinivasan S, Dutra A, Nussbaum RL, & Dreyfuss G (1995). The fragile X mental retardation syndrome protein interacts with novel homologs FXR1 and FXR2. The EMBO Journal, 14(21). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer SE, Doll SG, Garcia ADR, & Akins MR (2017). Splice form-dependent regulation of axonal arbor complexity by FMRP. Developmental Neurobiology, 77(6), 738–752. 10.1002/dneu.22453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorio DAR, Jackson CM, Liu Y, Rubel EW, & Wang Y (2017). Cellular distribution of the fragile X mental retardation protein in the mouse brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 525(4), 818–849. 10.1002/cne.24100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]