Adolescents with access to guns pose a substantial public health risk; we sought to determine if implementing NICS changed youth gun-carrying behavior.

Abstract

Video Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Despite being unable to purchase firearms directly, many adolescents have access to guns, leading to increased risk of injury and death. We sought to determine if the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) changed adolescents’ gun-carrying behavior.

METHODS:

We performed a repeated cross-sectional study using National Youth Risk Behavior Survey data from years 1993 to 2017. We used a survey-weighted multivariable logistic regression model to determine if the NICS had an effect on adolescent gun carrying, controlling for state respondent characteristics, state laws, state characteristics, the interaction between the NICS and state gun laws, and time.

RESULTS:

On average, 5.8% of the cohort reported carrying a gun. Approximately 17% of respondents who carried guns were from states with a universal background check (U/BC) provision at the point of sale, whereas 83% were from states that did not have such laws (P < .001). The model indicated that the NICS together with U/BCs significantly reduced gun carrying by 25% (adjusted relative risk = 0.75 [95% confidence interval: 0.566–0.995]; P = .046), whereas the NICS independently did not (P = .516).

CONCLUSIONS:

Adolescents in states that require U/BCs on all prospective gun buyers are less likely to carry guns compared with those in states that only require background checks on sales through federally licensed firearms dealers. The NICS was only effective in reducing adolescent gun carrying in the presence of state laws requiring U/BCs on all prospective gun buyers. However, state U/BC laws had no effect on adolescent gun carrying until after the NICS was implemented.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Adolescents obtain guns from friends and family members. The National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) was implemented to prevent firearm sales to individuals with criminal records. Not all states require background checks, producing variation in accessibility to and availability of guns for both adults and minors.

What This Study Adds:

Our study suggests that the NICS alone does not decrease gun-carrying behaviors in adolescents. However, adolescents residing in states with laws that require background checks for all firearm purchases did have reduced gun carrying after NICS implementation.

During adolescence, youth tend to take more risks and have less impulse control compared with adults.1 As a result, their ability to access guns may lead to misuse, criminal activity, and injury. Both US federal and state laws have set minimum ages for gun purchases; however, age requirements for possessing firearms vary by state.2 Although restricted in purchasing guns, adolescents can still obtain guns indirectly through a “straw-purchase,” that is, someone purchasing on behalf of another person, or directly from unlicensed or illegal gun dealers. In addition, they may have access to guns owned by family or friends.2–4 Adolescents’ access to guns increases the risk of firearm injuries to their peers and to themselves and also increases society’s health care spending.5,6 Approximately 86% of homicide victims ages 10 to 24 are killed by firearms, 43% of youth suicides involve firearms, and 44% of firearm injury costs are generated by people ages 15 to 24.7–9 This suggests that current policies to prevent gun sales to minors may not be effective at reducing adolescent firearm access.

One approach to controlling firearm sales is conducting background checks on prospective buyers. This type of approach was first adopted through California State legislation.10 In 1994, the federal Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act was implemented, and the background check mandate was expanded nationally.11 To better enforce the Brady Act, the Federal Bureau of Investigation launched the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) in 1998, which is used to determine if prospective buyers are eligible to purchase firearms.12 The NICS allows background checks to be conducted through 4 federal databases (the National Crime Information Center, the Interstate Identification Index, the Department of Homeland Security’s US Immigration and Customs Enforcement databases, and the NICS index), expediting checks and reducing default approval of purchases to people ineligible to possess firearms.13 More than 280 million background checks have been conducted, and 1.5 million denials have been made through the NICS.12,14,15 Denials may reduce gun ownership by limiting direct sales as well as indirectly decreasing availability of guns in the secondary market, in turn, potentially limiting adolescents’ access to guns. One shortcoming of the federal background check requirement is that it only applies to licensed gun dealers but not to unlicensed private gun sellers, which generates a “loophole” in the law.16 As a result, prospective gun buyers denied by licensed sellers may pursue purchases through private sellers, making the federal background check requirement less effective in reducing sales to ineligible buyers, including adolescents.

To our knowledge, no study has specifically investigated whether the NICS reduces adolescent gun carrying. Research has primarily been focused on firearm-related deaths, and few studies have examined effects of laws on gun-carrying behavior in adolescents, a population at increased risk for firearm mishandling.17 Our objective for this study is to determine if the NICS affects adolescent gun carrying, controlling for and examining interactions with state background check laws. We hypothesize that the NICS serves as a tool for providing timely and more thorough background checks yet may be less effective at reducing adolescent gun carrying in states that do not require background checks for all gun sales.

Methods

Data

We collected cross-sectional survey data from the national, school-based Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) from 1993 to 2017. The YRBS is a biennial survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. With a 3-staged cluster-sampling survey design, data from the YRBS provides a nationally representative sample of US public and private school students in grades 9 to 12. A self-administered questionnaire is used to collect anonymous and voluntary responses from participating students on their demographics and health risk behaviors. In total, there were 191 391 responses over the period between 1993 and 2017. Details about YRBS sampling strategies and methodologies are reported elsewhere.18

Approximately 2.0% of the responses were missing state identifiers and 4.1% were missing information on the gun carrying survey item, so these responses were dropped from the analysis. Our final analysis included responses from 179 857 students from 1993 to 2017.

Measures

Gun Carrying

The YRBS in 1993–2015 was used to assess whether students carried guns by asking “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you carry a gun?” We dichotomized this question to flag those students who carried a gun on at least 1 day during the 30 days before the survey. In 2017, this question was modified to “During the past 12 months, on how many days did you carry a gun? (Do not count the days when you carried a gun only for hunting or for a sport, such as target shooting).” We used this question to flag the students if they carried a gun for at least 1 day in the past 12 months.

Pre- and Post-NICS

In November 1998, the Federal Bureau of Investigation launched the NICS. We used 1998 as the reference point and created the binary variable pre- and post-NICS period for YRBS data before and after 1998. Because the YRBS is biennial, data from years 1993–1997 were classified as pre-NICS, and data from years 1999–2017 were classified as post-NICS.

Universal Background Check

We created a data set of those states that have a requirement for a background check at the point of sale of any firearm. States, including California (1991), Colorado (2013), Connecticut (2013), Delaware (2013), the District of Columbia (1975), Maryland (2010), New York (2013), Oregon (2015), Pennsylvania (2010), Rhode Island (1990), and Washington (2014), have implemented universal background checks (U/BCs) either by requiring background checks for all gun sales conducted by licensed sellers only or by requiring licensed gun sellers, in addition to private sellers, to conduct background checks on all prospective buyers.16 Eight states, Hawaii (2013), Illinois (2013), Massachusetts (2006), New Jersey (2011), Iowa (2011), Michigan (2006), Nebraska (2010), and North Carolina (2014), implemented firearm background check requirements on private sales primarily by prohibiting private sellers to sell to buyers who did not have a requisite state license or permit and by requiring a background check before issuing the license or permit. Two of these states, Connecticut and New York, require both U/BCs and state permits to purchase firearms.

The YRBS responses were dichotomized into 2 groups: (1) respondents in states without any background check laws and (2) respondents in states with some background check laws at the point of sale or in states that require a license or permit after a background check, which was classified as U/BC. A state was identified as a U/BC state starting from the year when the law was enacted in that state.

Other Measures

Respondent-level variables included age, sex, race and ethnicity, state of residence, and whether the student reported any threat. The “threat” variable was obtained from the YRBS question “During the past 12 months, how many times has someone threatened or injured you with a weapon, such as a gun, knife, or club, on school property?” Studies have revealed that these variables are associated with the likelihood of gun carrying among adolescents.19,20 We also collected state-level data on annual estimates of median income in current and 2016 Consumer Price Index adjusted dollars and data on the percentage of the total population in urban areas from the decennial US Census.21,22

Statistical Analysis

Univariate, bivariate, and multivariable analyses were performed in Stata/SE version 14.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) by using the svy command to account for the complex sample design of the national YRBS. All estimates presented in the results are weighted estimates. Weighted estimates, with appropriate accounting of the survey design, reflect the national population estimate. α was set at .05. t tests and χ2 tests were used to test bivariate associations. National estimates of the percentage of high school students carrying guns is reported as well as the percentage of students carrying guns by each study variable.

The longitudinal nature of the data set allowed us to examine the effect of U/BCs before and after implementation of the NICS given the availability of responses from states that had U/BC laws in place before the NICS was implemented. To address our study objective, a longitudinal multivariable logistic regression model was used to examine the effects of the NICS and state U/BCs while controlling for age, race, ethnicity, sex, feeling threatened, and state of residence. It also controlled for time-varying effects, including implementation of the NICS, state U/BC policies, and annual state characteristics, which includes median income and the percentage of the population living in rural areas. It was used to examine the effect of the pre- and post-NICS period on the U/BC variable by using an interaction term. The interaction term between U/BC state and pre- and post-NICS period was used to examine the simultaneous effect of the NICS and state-specific U/BC laws. A postestimation command in Stata (adjrr) was used to estimate the adjusted relative risks (ARRs) for each variable in the model. Subpopulation analyses within the svy command were done to examine the effect of U/BCs on the observations before and after 1998.

A sensitivity analysis used to examine nonfirearm weapon-carrying behavior, such as knives, was conducted to determine if laws targeting firearm purchases specifically affected gun carrying. In the sensitivity analysis, we compared students who reported carrying a weapon (but did not report carrying a gun) with those who did not carry a weapon.

Results

On average, 5.8% of high school students in the United States carried guns across the entire study period. Of those who carried guns, ∼17% were from the states that had U/BCs at the point of gun sales, whereas 83% were from states that did not have U/BCs (P < .001). Adolescents who carried guns were older (16–18 years; P < .001), male (P < .001), and white (P < .001). Students who were threatened reported carrying guns more than those who were not (28% vs 6%; P < .001) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sample Characteristics, Nationally Weighted Sample

| Variables | Total Sample | By Gun-Carrying Behavior | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 172 456) | Yes (n = 10 544) | P | ||

| Carried a gun, n (%) | ||||

| No | 172 456 (94.24) | — | — | — |

| Yes | 10 544 (5.76) | — | — | — |

| NICS period, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| Pre-NICS | 41 591 (22.73) | 38 680 (22.43) | 2912 (27.61) | |

| Post-NICS | 141 409 (77.27) | 133 777 (77.57) | 7633 (72.39) | |

| State U/BC, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| No | 141 506 (77.33) | 132 720 (76.96) | 8786 (83.322) | |

| Yes | 41 495 (22.67) | 39 736 (23.04) | 1758 (16.68) | |

| Age, y, mean (SE) | 16.07 (0.01) | 16.06 (0.01) | 16.12 (0.02) | .007 |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||

| 12–15 y | 64 449 (35.31) | 61 017 (35.47) | 3432 (32.71) | <.001 |

| 16–18 y | 118 051 (64.69) | 110 992 (64.53) | 7059 (67.29) | |

| Sex, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| Male | 93 081 (51.02) | 83 942 (48.82) | 9139 (87.24) | |

| Female | 89 344 (48.98) | 88 007 (51.18) | 1337 (12.76) | |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 111 356 (61.46) | 105 447 (61.75) | 5909 (56.74) | <.001 |

| African American | 24 875 (13.73) | 23 052 (13.50) | 1823 (17.51) | <.001 |

| Other | 44 942 (24.81) | 42 260 (24.75) | 2682 (25.75) | .221 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | .263 | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 163 384 (90.18) | 153 942 (90.15) | 9442 (90.66) | |

| Hispanic | 17 789 (9.82) | 16 817 (9.85) | 972 (9.34) | |

| Any threat felt, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| No | 169 484 (92.70) | 161 907 (93.97) | 7576 (72.00) | |

| Yes | 13 338 (7.30) | 10 392 (6.03) | 2946 (28.00) | |

| State median income, $, mean (SE) | 45 769.29 (410.30) | 45 900.13 (414.37) | 43 629.28 (430.98) | <.001 |

| State rural population, % (SE) | 22.80 (0.63) | 22.62 (0.62) | 25.74 (0.82) | <.001 |

| Year of survey, n (%) | <.001 | |||

| 1993 | 15 092 (8.25) | 13 913 (8.07) | 1179 (11.18) | |

| 1995 | 10 369 (5.67) | 9588 (5.56) | 781 (7.41) | |

| 1997 | 16 130 (8.81) | 15 178 (8.80) | 952 (9.03) | |

| 1999 | 15 240 (8.33) | 14 490 (8.40) | 750 (7.11) | |

| 2001 | 13 107 (7.16) | 12 359 (7.17) | 748 (7.09) | |

| 2003 | 14 516 (7.93) | 13 637 (7.91) | 879 (8.34) | |

| 2005 | 13 441 (7.35) | 12 713 (7.37) | 728 (6.90) | |

| 2007 | 13 340 (7.29) | 12 653 (7.34) | 687 (6.52) | |

| 2009 | 15 741 (8.60) | 14 805 (8.59) | 936 (8.87) | |

| 2011 | 14 232 (7.78) | 13 503 (7.83) | 729 (6.92) | |

| 2013 | 13 270 (7.25) | 12 539 (7.27) | 731 (6.94) | |

| 2015 | 14 520 (7.93) | 13 752 (7.97) | 768 (7.28) | |

| 2017 | 14 004 (7.65) | 13 327 (7.73) | 677 (6.42) | |

All percentages are column percentages. —, not applicable.

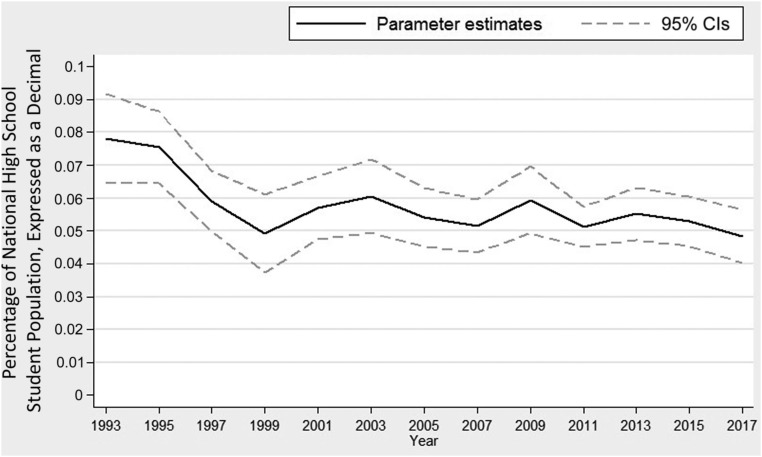

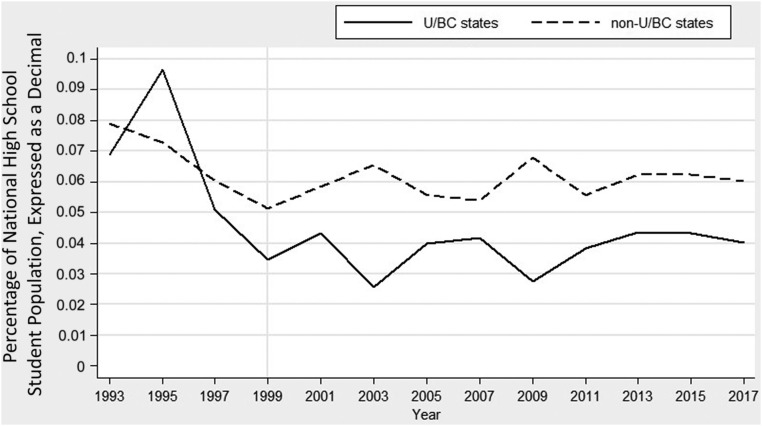

On average, we found a decline in gun carrying until 1999. Since 1999, the trend begins to plateau over time (Fig 1). When comparing states with and without U/BCs, we observe that before NICS implementation, there was no difference in adolescent gun-carrying rates between U/BC and non-U/BC states. However, a difference emerges and continues after 1999, with lower proportions of students reporting gun carrying in U/BC states than in non-U/BC states throughout the remaining study period (Fig 2).

FIGURE 1.

Trends of high school students’ gun-carrying behavior, 1993–2017. The figure reveals trends of gun carrying among all adolescents from 1993 to 2017. Percentages are expressed as decimals.

FIGURE 2.

Trends of high school students’ gun-carrying behavior by non-U/BC and U/BC states, 1993–2017. Percentages are expressed as decimals.

The results of the pooled and stratified weighted multivariable logistic regression model are presented as ARRs of gun carrying by high school students. During the estimation process, we controlled for age, sex, race, ethnicity, threat, state-level median income, and state percentage of the population living in rural areas. The pooled model includes the interaction between the NICS and U/BC. The pooled model reveals that the interaction term is significant, indicating that the NICS with U/BC reduced the risk of gun carrying by 25% (ARR = 0.75 [95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.566–0.995]; P = .046). There was no significant effect of U/BCs during the pre-NICS period whereas, during the post-NICS period, adolescents in states with U/BCs had a 15% reduction in the risk of carrying guns (ARR = 0.85 [95% CI: 0.738–0.984]; P = .029). Boys, African Americans, and those who received threats had a significantly higher risk of carrying guns. In the pooled analysis, ethnicity was not associated with the risk of gun carrying. However, Hispanic students, compared with non-Hispanic students, in the pre-NICS model had a higher risk of gun carrying (ARR = 1.32 [95% CI: 1.03–1.69]; P = .028), whereas they had lower risk in the post-NICS period (ARR = 0.80 [95% CI: 0.72–0.89]; P < .001). Older students in the pre- (12%; ARR = 1.12; P < .001) and post-NICS (20%; ARR = 1.20; P < .001) periods had an increased risk of carrying guns compared with younger adolescents. For each percent increase in the rural population in the post-NICS period, the risk of gun carrying increased by 1.3% (P < .001). Median income had no effect on gun carrying in the post-NICS period (P = .464) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

ARRs of Carrying Guns, Nationally Weighted Sample

| Pooled Sample | Pre-NICS Years | Post-NICS Years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARR (95% CI) | P | ARR (95% CI) | P | ARR (95% CI) | P | |

| NICS period | ||||||

| Pre-NICS | Reference | — | — | — | — | — |

| Post-NICS | 0.951 (0.819–1.106) | .516 | — | — | — | — |

| State U/BC | ||||||

| No | Reference | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 1.170 (0.913–1.498) | .215 | 1.101 (0.859–1.410) | .448 | 0.852 (0.738–0.984) | .029 |

| NICS + U/BC | 0.750 (0.566–0.995) | .046 | — | — | — | — |

| Age group, y | ||||||

| 12–15 | Reference | — | — | — | — | — |

| 16–18 | 1.121 (1.052–1.195) | .001 | 0.933 (0.809–1.076) | .338 | 1.198 (1.118–1.284) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | Reference | — | — | — | — | — |

| Female | 0.171 (0.156–0.188) | <.001 | 0.174 (0.140–0.215) | <.001 | 0.169 (0.153–0.187) | <.001 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | Reference | — | — | — | — | — |

| African American | 1.371 (1.242–1.513) | <.001 | 1.764 (1.523–2.044) | <.001 | 1.228 (1.080–1.395) | .002 |

| Other | 1.280 (1.172–1.397) | <.001 | 1.364 (1.098–1.694) | .005 | 1.245 (1.133–1.367) | <.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic | Reference | — | — | — | — | — |

| Hispanic | 0.937 (0.847–1.037) | .210 | 1.32 (1.031–1.690) | .028 | 0.800 (0.717–0.893) | <.001 |

| Any threat felt | ||||||

| No | Reference | — | — | — | — | — |

| Yes | 4.029 (3.726–4.358) | <.001 | 3.766 (3.188–4.449) | <.001 | 4.127 (3.777–4.510) | <.001 |

| State median income, $, thousands | 0.994 (0.987–1.001) | .082 | 0.973 (0.962–0.985) | <.001 | 0.997 (0.989–1.005) | .464 |

| State rural population, % | 1.013 (1.008–1.017) | <.001 | 1.008 (0.998–1.018) | .102 | 1.013 (1.008–1.018) | <.001 |

The pooled model includes data from the entire study period. The pre- and post-NICS models reflect data from those respective periods. —, reference category.

From the sensitivity analysis, we observed that U/BCs had no effect (P = .090) in the control condition (nonfirearm weapon carrying), helping to rule out the possibility of spurious associations between background checks and adolescent gun carrying (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Sensitivity Analysis to Estimate Nonfirearm Weapon-Carrying Behavior

| Pooled Sample | ||

|---|---|---|

| aOR (95% CI) | P | |

| NICS period | ||

| Pre-NICS | Reference | — |

| Post-NICS | 1.075 (0.947–1.221) | .26 |

| State U/BC | ||

| No | Reference | — |

| Yes | 1.119 (0.913–1.371) | .28 |

| NICS + U/BC | 0.825 (0.659–1.034) | .09 |

| Age group, y | ||

| 12–15 | Reference | — |

| 16–18 | 0.989 (0.942–1.038) | .65 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Reference | — |

| Female | 0.246 (0.231–0.263) | <.001 |

| Race | ||

| White | Reference | — |

| African American | 0.736 (0.670–0.808) | <.001 |

| Other | 0.957 (0.880–1.041) | .31 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic | Reference | — |

| Hispanic | 0.928 (0.843–1.021) | .13 |

| Any threat felt | ||

| No | Reference | — |

| Yes | 3.278 (3.032–3.545) | <.001 |

| State median income, $, thousands | 0.992 (0.985–0.998) | .01 |

| State rural population, % | 1.004 (1.001–1.008) | .04 |

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; —, reference category.

Discussion

Authors of several studies have investigated the effects of both federal and state background check laws on the adult population.23,24 Our study of adolescents both supports and differs from studies in adults, indicating that more work needs to be done to understand the downstream effects on minors of gun-purchasing laws aimed at adults. The authors of 1 study reported that the Brady Act’s impact on firearm injury and overall homicide and suicide rates only significantly reduced suicide rates in those aged >55 years.11 In 2001, a study revealed that California’s background check law reduced violent misdemeanants’ subsequent arrests for gun possession and violent crimes.25 This suggests that increasing background checks for gun purchases may potentially reduce violent crimes and criminal charges because firearms may be less accessible, and carrying a deadly weapon substantially alters the severity of a criminal charge.26,27 The authors of another study examined the association of various state background check laws with firearm homicides, finding that stricter background check regulations were associated with lower firearm homicide rates.28 Recently, evidence that suicide-prone populations residing in states with less strict gun laws were at an increased risk of a completed suicide by firearm.29 In light of increasing rates of suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents, it may be important to evaluate the efficacy of background checks in reducing unintended access to firearms because gunshots are the most fatal means of completing suicide.30,31 Findings from the above studies suggest that federal and state background checks laws can reduce gun-related crimes and firearm deaths in the adult population as well as reduce adverse outcomes of firearm ownership.29,32,33

In our study, we did not find evidence revealing that implementation of the NICS in 1998 was independently associated with a national reduction in adolescents’ gun carrying when controlling for individual, state, and time effects. We found that adolescents living in states that required U/BCs on all prospective gun buyers were less likely to carry guns compared with adolescents living in states that only require background checks on purchases through federally licensed gun dealers. This finding is similar to that of other studies that found that state-specific gun laws reduced youth gun carrying.17 However, our results also indicate that states’ U/BC laws were not effective before NICS implementation. This suggests that the NICS may be more effective in reducing adolescent gun carrying if all gun buyers were required to have a background check. When we examined the interaction between the NICS and state U/BC laws, we found that together they significantly reduced the risk of adolescent student gun carrying by 25%. Our results may reflect several factors. First, it is possible that adolescents who purchase guns for themselves may be more likely to purchase from a private seller, particularly if they do not meet minimum age requirements. Requiring all gun sales to be made through licensed dealers, who either require a background check or a gun permit issued only after a background check, could deter gun purchases by adolescents. It is also possible that adults who would sell or allow minors access to a firearm would be less likely to be approved for a firearm purchase, thus giving them fewer options to purchase guns when residing in areas that require background checks on all buyers.

It is important to note that factors in addition to background check laws on adult gun purchases likely play a larger role in adolescent gun carrying. Adolescents often obtain firearms from their own home, purchased legally by adults who may not always secure weapons (either within a safe or using another locking mechanism).34 A cross-sectional survey of adolescents attending New York City high schools on their perception of firearms revealed that 41% of students lived with an adult who possessed a firearm.34 These students were more likely to be found in residences with gun-supporting families that witnessed gun violence at some point in their lives. Thus, gun-safety storage programs may be beneficial to both rural- and urban-dwelling families, particularly those with high school youth, because researchers found these programs to be helpful across populations.35 Storing firearms securely reduces the likelihood that a minor residing in the home would obtain it without an adult’s knowledge as well as prevents gun theft, which is an important source of guns used in crimes or possibly sold in illegal markets to minors.36

With our study, we add to the literature by examining how federal and state policy changes over a 24-year period, approximately a generation, interact to affect adolescent gun carrying. Specifically, we found that state laws moderate the effect of federal background check laws, which may suggest that implementing U/BCs at the national level could increase efficacy of the NICS. The NICS background check system is limited because of the potential to sidestep the system through private sales. Implementing U/BCs nationally may decrease the number of guns accessible to adolescents and, in turn, reduce their gun carrying. On the basis of studies in adults, this could also indirectly prevent firearm-related suicides, homicides, and injuries as well as reduce the likelihood of being charged with a felony that could affect employment opportunities throughout life.33,37–40 Strengthening background check policies and making safety training available to all gun owners on proper storage of firearms may decrease the number of firearms acquired by adolescents, preventing injuries that are costly both financially and to quality of life.41–43

Our analyses were based on cross-sectional data of adolescents sampled in different years, and therefore conclusions about association, rather than causality, between background check laws and adolescent gun carrying can only be made. We attempted to address this using longitudinal analyses that allowed for time-varying effects, such as state U/BC laws and annual changes in state-level variables, to account for latent changes in gun carrying nationally. Another limitation is that the laws examined do not directly apply to adolescents. It is likely that the effects of these laws are mediated by adult behavior, and whether this changed the availability of firearms in the respondent’s household is unknown. Although a strength of the YRBS is that it is a long-running, nationally representative data source, information on other important outcomes is limited, and we only examined gun carrying. Studying outcomes such as gun use or gun-related injury would provide additional public health insights. The YRBS was also missing outcome data on 4.1% of the sample. However, the weighted analysis used in the study is 1 approach to produce unbiased estimates of a population. Another limitation is that data are self-reported, and adolescents not enrolled in school are excluded, likely making our estimates of adolescent gun carrying low. Finally, experiences outside of school, such as bullying (eg, in person, through text messaging, or in cyber or social media settings), anxiety around mass shootings, and other factors that might influence gun carrying, could not be accounted for. We attempted to control for this using the respondent’s self-reported variable of being threatened or injured on school property, but we do not have data on whether adolescents experienced threats outside of school or harassment online, partially because the early years of these data predate widespread Internet use.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that federal systems for conducting background checks do not independently reduce adolescent gun carrying on a national level. This may be because the NICS effect was only significant in the presence of state U/BC laws. Additionally, U/BC laws did not independently affect adolescent gun carrying before implementation of the NICS. Therefore, it is possible that both federal and state background check laws work together to reduce gun carrying in high school students.

Glossary

- ARR

adjusted relative risk

- CI

confidence interval

- NICS

National Instant Criminal Background Check System

- U/BC

universal background check

- YRBS

Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Footnotes

Dr Timsinia performed the data analysis and drafted the manuscript; Dr Qiao assisted in the study design, acquired data, and drafted the manuscript; Mr Mongalo drafted the manuscript; Ms Vetor drafted the manuscript and interpreted results; Dr Carroll provided critical feedback on the study design, interpreted results, and made critical manuscript revisions; Dr Bell conceptualized and designed the study, interpreted results, and drafted the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by grants KL2TR002530 and UL1TR002529 from the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2019-2334.

References

- 1.Casey BJ, Jones RM, Hare TA. The adolescent brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:111–126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence Minimum age to purchase & possess. 2016. Available at: http://lawcenter.giffords.org/gun-laws/policy-areas/who-can-have-a-gun/minimum-age/. Accessed August 9, 2018

- 3.Teret SP, Wintemute GJ. Policies to prevent firearm injuries. Health Aff (Millwood). 1993;12(4):96–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemenway D. Reducing firearm violence. Crime Justice. 2017;46(1):201–230 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rattan R, Parreco J, Namias N, Pust GD, Yeh DD, Zakrison TL. Hidden costs of hospitalization after firearm injury: national analysis of different hospital readmission. Ann Surg. 2018;267(5):810–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spitzer SA, Staudenmayer KL, Tennakoon L, Spain DA, Weiser TG. Costs and financial burden of initial hospitalizations for firearm injuries in the United States, 2006-2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(5):770–774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howell EM, Abraham P. The Hospital Costs of Firearm Assaults. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Center for Disease Control and Prevention Youth violence: facts at a glance. 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/yv-datasheet.pdf. Accessed August 9, 2018

- 9.Harvard Injury Control Research Center; Suicide Prevention Resource Center . Youth Suicide: Findings From a Pilot for the National Violent Death Reporting System. Waltham, MA: Suicide Prevention Resource Center; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence The California model: twenty years of putting safety first. 2013. Available at: http://lawcenter.giffords.org/the-california-model-twenty-years-of-putting-safety-first/. Accessed August 9, 2018

- 11.Ludwig J, Cook PJ. Homicide and suicide rates associated with implementation of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act. JAMA. 2000;284(5):585–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Federal Bureau of Investigation National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS). 2013. Available at: https://www.fbi.gov/services/cjis/nics#Reports-%20Statistics. Accessed August 9, 2018

- 13.Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence Background check procedures. 2016. Available at: http://lawcenter.giffords.org/gun-laws/policy-areas/background-checks/background-check-procedures/. Accessed August 9, 2018

- 14.Federal Bureau of Investigation NICS firearm checks: month/year. 2018. Available at: https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/nics_firearm_checks_-_month_year.pdf/view. Accessed August 9, 2018

- 15.Federal Bureau of Investigation Federal denials. 2018. Available at: https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/federal_denials.pdf/view. Accessed August 9, 2018

- 16.Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. Universal background checks. 2016. Available at: http://lawcenter.giffords.org/gun-laws/policy-areas/background-checks/universal-background-checks/. Accessed October 11, 2018

- 17.Xuan Z, Hemenway D. State gun law environment and youth gun carrying in the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):1024–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brener ND, Kann L, Shanklin S, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Methodology of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System–2013. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62(RR-1):1–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pham TB, Schapiro LE, John M, Adesman A. Weapon carrying among victims of bullying. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20170353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kemal S, Sheehan K, Feinglass J. Gun carrying among freshmen and sophomores in Chicago, New York City and Los Angeles public schools: the Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2007-2013. Inj Epidemiol. 2018;5(suppl 1):12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iowa State University Iowa Community Indicators Program; Iowa State University . Urban Percentage of the Population for States, Historical. Ames, IA: 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 22.US Census Bureau Current population survey. Available at: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/data-detail.html. Accessed November 7, 2018

- 23.Miller M, Hepburn L, Azrael D. Firearm acquisition without background checks: results of a national survey. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):233–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthay EC, Galin J, Rudolph KE, Farkas K, Wintemute GJ, Ahern J. In-state and interstate associations between gun shows and firearm deaths and injuries: a quasi-experimental study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(12):837–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wintemute GJ, Wright MA, Drake CM, Beaumont JJ. Subsequent criminal activity among violent misdemeanants who seek to purchase handguns: risk factors and effectiveness of denying handgun purchase. JAMA. 2001;285(8):1019–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perkins C. National Crime Victimization Survey, 1993-2001: Weapon Use and Violent Crime. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller M, Azrael D, Hemenway D. Firearm availability and unintentional firearm deaths, suicide, and homicide among 5-14 year olds. J Trauma. 2002;52(2):267–274–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruddell R, Mays GL. State background checks and firearms homicides. J Crim Justice. 2005;33(2):127–136 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alban RF, Nuño M, Ko A, Barmparas G, Lewis AV, Margulies DR. Weaker gun state laws are associated with higher rates of suicide secondary to firearms. J Surg Res. 2018;221:135–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiao N, Bell TM. Indigenous adolescents’ suicidal behaviors and risk factors: evidence from the National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19(3):590–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bell TM, Qiao N, Jenkins PC, Siedlecki CB, Fecher AM. Trends in emergency department visits for nonfatal violence-related injuries among adolescents in the United States, 2009-2013. J Adolesc Health. 2016;58(5):573–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monuteaux MC, Lee LK, Hemenway D, Mannix R, Fleegler EW. Firearm ownership and violent crime in the U.S.: an ecologic study. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(2):207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee LK, Fleegler EW, Farrell C, et al. Firearm laws and firearm homicides: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):106–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kahn DJ, Kazimi MM, Mulvihill MN. Attitudes of New York City high school students regarding firearm violence. Pediatrics. 2001;107(5):1125–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coyne-Beasley T, Schoenbach VJ, Johnson RM. “Love our kids, lock your guns”: a community-based firearm safety counseling and gun lock distribution program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(6):659–664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hemenway D, Azrael D, Miller M. Whose guns are stolen? The epidemiology of gun theft victims. Inj Epidemiol. 2017;4(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parikh K, Silver A, Patel SJ, Iqbal SF, Goyal M. Pediatric firearm-related injuries in the United States. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(6):303–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joudi N, Tashiro J, Golpanian S, Eidelson SA, Perez EA, Sola JE. Firearm injuries due to legal intervention in children and adolescents: a national analysis. J Surg Res. 2017;214:140–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tseng J, Nuño M, Lewis AV, Srour M, Margulies DR, Alban RF. Firearm legislation, gun violence, and mortality in children and young adults: a retrospective cohort study of 27,566 children in the USA. Int J Surg. 2018;57:30–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hepburn L, Azrael D, Miller M, Hemenway D. The effect of child access prevention laws on unintentional child firearm fatalities, 1979-2000. J Trauma. 2006;61(2):423–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tashiro J, Lane RS, Blass LW, Perez EA, Sola JE. The effect of gun control laws on hospital admissions for children in the United States. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(4 suppl 1):S54–S60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monuteaux MC, Azrael D, Miller M. Association of increased safe household firearm storage with firearm suicide and unintentional death among US youths. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(7):657–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]