The understanding of suffering in pediatrics has changed dramatically over time. This history highlights the rise of pediatric palliative care as a philosophy and discipline.

Abstract

Most pediatric clinicians aspire to promote the physical, emotional, and developmental well-being of children, hoping to bestow a long and healthy life. Yet, some infants, children, and adolescents confront life-threatening illnesses and life-shortening conditions. Over the past 70 years, the clinician’s response to the suffering of these children has evolved from veritable neglect to the development of pediatric palliative care as a subspecialty devoted to their care. In this article, we review the history of how clinicians have understood and responded to the suffering of children with serious illnesses, highlighting how an initially narrow focus on anxiety eventually transformed into a holistic, multidimensional awareness of suffering. Through this transition, and influenced by the adult hospice movement, pediatric palliative care emerged as a new discipline. Becoming a discipline, however, has not been a panacea. We conclude by highlighting challenges remaining for the next generation of pediatric palliative care professionals to address.

Most pediatric clinicians aspire to promote the physical, emotional, and developmental well-being of children, hoping to bestow a long and healthy life. In the midst of childhood, however, some infants, children, and adolescents confront life-threatening illnesses and life-shortening conditions. Over the past 70 years, the clinician’s response to the suffering of these children has evolved from veritable neglect to the development of pediatric palliative care as a subspecialty devoted to their care. This subspecialty now encompasses inpatient and outpatient care as well as hospital-based and community-based services. Most importantly, pediatric palliative care now represents a philosophy of care that extends beyond any particular subspecialty. In this article, we explore the history of the palliative care philosophy in pediatrics. Through the study of this history, we can recognize how far pediatrics has come while also recognizing persistent challenges to providing effective care.

Suffering is experienced by persons, not merely by bodies, and has its source in challenges that threaten the intactness of the person as a complex social and psychological entity.

Eric Cassel, MD1

The Age of Ignorance: Before the 1970s

Before the 20th century, nearly one-third of children died acutely before they turned 16.2 This clinical picture improved only gradually until the mid-20th century.3 After World War II, advancing medical technology, like antimicrobial agents, intravenous infusions, and tank respirators (ie, iron lungs), allowed children with serious illnesses to survive longer.4,5 These advancements also prolonged the process of dying, creating the potential for protracted suffering. As Olmsted6 commented in 1970: “Death for children no longer comes quickly and mercifully.”

Although suffering is commonly recognized today as a complex state of distress that cannot be reduced to individual symptoms,7 this holistic understanding did not emerge in pediatrics until recent decades. Instead, clinicians initially focused narrowly on anxiety. In 1955, Bozeman, Sutherland, and Orbach8,9 published 1 of the earliest psychological studies of dying children. This 2-part series was focused primarily on the anxiety of mothers but also reported observations of the children’s experiences:

The children were extraordinarily quiet, sometimes apathetic. . .Their physical condition during hospitalization was largely responsible for limited activity, but the anxiety over separation from their mothers created additional limitations. Crying and moaning were common when mothers were present and increased shortly after they had left.9

Hospitals at that time had rigid restrictions on visiting hours, limiting visits with parents to a few hours each day10 and a few days per week,9 which negatively impacted parents and children.11,12

Richmond and Waisman,13 both pediatricians, published an article in 1955 that painted a similar picture: “In general, children seem to have reacted with an air of passive acceptance and resignation. Associated with this there often seemed to be an atmosphere of melancholia.” Despite identifying several diagnostic criteria of what we now call depression (apathy, resignation, and melancholia), investigators employed anxiety as the lens of psychological investigation for another decade. This focus was due in part to a societal preoccupation with anxiety as the source of many maladies at that time, and a limited understanding of depression.14 Additionally, the widespread belief that children lacked an awareness of death and did not experience existential loss might have led psychologists to question whether children could experience depression.

None of these studies, however, directly engaged dying children. In 1963, Morrissey,15 a social worker, conducted the first study in which these children were interviewed, finding high levels of anxiety. He proposed 4 manifestations of anxiety: verbal, behavioral (eg, withdrawal from peers, regressive play), physiologic (eg, nausea, poor appetite), and symbolic through play. As in earlier studies, Morrissey15 did not recognize that some “expressions of anxiety” were likely manifestations of end-of-life symptoms. This study was remarkable, however, for its active engagement with dying children.

In contrast to this emphasis on anxiety, clinicians caring for dying children seldom mentioned pain in the 1950s.16 One early discussion of pain by Blom,11 a psychiatrist, in 1958, was focused on a child with severe burns. An excerpt highlights how some clinicians grew frustrated with children’s protestations to severely painful procedures: “The reactions of these children may provoke dissatisfaction, dislike, avoidance, and antagonism in hospital personnel who care for them. It is often hard for hospital personnel to understand why these children feel so overwhelmed.”11

In the 1960s, a few clinicians began to challenge the broad resistance to prescribing opioids in children. Toch, a pediatric oncologist, wrote a detailed account of cancer pain in children in 1964.17 “Pain does become a problem towards the end of life in children with cancer, and the use of fairly potent analgesics is perfectly ethical. Morphine and scopolamine or other potent analgesic mixtures can be very soothing to the afflicted patient when all other measures fail.”18 Toch was arguing against a broad hesitance to prescribe opioids to children, in part caused by an assumption that children did not experience pain to the same extent as adults. Green,4 a pediatrician, directly addressed this misperception in 1967: “A few children tend to suffer in silence, but there is no evidence that the chronically ill patient is better able to tolerate pain than a healthy child (although I think this is frequently assumed) or that chronicity breeds stoicism.”

Even when severe pain was recognized, the fear of causing serious harm with opioids led to prescriptions of miniscule doses. This hesitance was due, in part, to lacking literature or recommendations for dosing of opioids in children. More than a decade would pass before such data became available.

This era of pediatrics was also notable for the lack of interdisciplinarity. In the 1950s, physicians urged that 1 pediatrician take responsibility for caring for these patients.16 This was a time of growing specialization in academic medicine, and large medical teams included students, residents, and other trainees. Solnit and Green19 warned in 1959 that “it is necessary to emphasize the importance of the one doctor when the most efficient hospital service is continuously faced with the weakening of this relationship.”

The proposed standards for this doctor were high. Green described his expectations in 1967:

The child and his family need to have access promptly to their physician if the need arises. . .Responsibility is not confined to office or clinic hours. The family should have a phone number through which the physician can always be reached with clear and definite arrangements for substituted coverage if he is not immediately available. . .This important relation is vitiated when care is provided by several physicians with no one identified as the child’s physician.4

Although these aspirations were laudable, little infrastructure existed to support the physician. In response to Green,4 a pediatrician wrote, “The pluralistic approach that Dr Green has described imposes severe demands on the time, emotions, and skills of the physician who is not part of a well-organized single-purpose cancer team. Incidentally, such teams exist in only a few medical centers.”20 Over time, as suffering was recognized and care grew in complexity, experts recognized that any 1 physician was insufficient to meet the full needs of these children.

Saunders and the Birth of Adult Hospice Philosophy

This age of ignorance was not unique to pediatrics. Clinicians in adult medicine were also hesitant to prescribe opioids, although to a lesser degree. Common practice for adults with “terminal illness” was to treat pain on an “as needed” basis, once pain had surged to intolerable levels, in hopes of preventing addiction.21 One man described his experience as a patient in a cancer ward in the 1970s, where he witnessed the suffering of another patient on his ward:

At the prescribed hour, a nurse would give Jack a shot of the synthetic analgesic, and this would control the pain for perhaps 2 hours or a bit more. Then he would begin to moan, or whimper, very low, as though he didn’t want to wake me. Then he would begin to howl, like a dog. . .Always the nurse would explain as encouragingly as she could that there was not long to go before the next intravenous shot – “Only about 50 minutes now.”22

Then the work of Cicely Saunders revolutionized terminal care for adults. Saunders trained as almoner (ie, social worker), nurse, and physician in the United Kingdom. While working as an almoner at London Hospital in 1948, she developed a strong bond with a dying patient named David Tasma. Their discussions “served as a fount of inspiration, and they later became emblematic of Saunders’ wider philosophy of care, but beyond them lay a great deal of further searching, both intellectual and spiritual.”23 After qualifying as a physician, she studied pain management of the incurably ill and worked at St. Joseph’s hospice for the dying poor.23 She advocated strongly for proactive prevention of pain with scheduled medications rather than reactive treatment, asserting that “constant pain needs constant control.”21 This proactive, intensive approach to pain management did not become prevalent in pediatrics until nearly 2 decades after gaining a foothold in adult end-of-life care.

Saunders also promoted the concept of “total pain,” which included mental, physical, social, and spiritual components.21,23,24 The growing popularity of this concept signaled the emergence of a holistic concern for suffering within medicine. Her work on “total pain” and team-based approaches to terminal care culminated in the founding of St. Christopher’s Hospice in 1967 and the launch of the adult hospice movement. In describing the hospice philosophy, Saunders wrote that “we continue to be concerned both with the sophisticated science of our treatments and with the art of our caring, bringing competence alongside compassion.”24 By the early 1970s, the hospice movement had spread to North America. Balfour Mount coined the term “palliative care” to describe a new, medical-based program in Montreal,25 and Florence Wald founded the first US hospice in Connecticut, both in 1974.23

“Total pain” had faint echoes in pediatrics. Evans and Edin26 proposed the concept of “total care, which concerns both the physical and emotional components of the disease,” and Green4 noted that “physical distress accentuates psychologic discomfort.” In a tangible demonstration of adult hospice philosophy making inroads into pediatrics, Saunders27 spoke in 1969 at a symposium on the care of dying children. In stark contrast to the “one doctor” approach, she argued strongly for the importance of a team:

I would give for the first principle of terminal care co-operation, or, perhaps better, community. The care of the dying must be a shared work. It is important that as we come to a dying patient we should not be saying to ourselves: ‘How can I help so and so?’ but instead: ‘This is this unit trying to help this person. I happen to be the one who is here at the moment.’”27

Although the palliative care philosophy was developing in pediatrics, practice lagged behind. Pain and other symptoms were largely underestimated and underappreciated until the late 1970s.

The 1970s: Making Visible the Suffering of Children

In the 1970s, a noticeable shift occurred away from nonstandardized, observational writings to more-rigorous, reproducible psychological studies of dying children. These studies expanded beyond anxiety to broader psychological problems, including alteration of self-concept, alteration of body image, difficulty in interpersonal relationships, and interference with future plans.28,29 Two figures played a major role in exploring and demonstrating the inner lives of these children.

In 1973, Spinetta, a psychologist, began a series of landmark studies of dying children’s awareness of death. Previously, medical professionals had debated whether children with fatal illnesses were aware of their dire circumstances. This debate led to opposing views about how to communicate with dying children about prognosis. Some advocated for a “protective approach,” whereas others urged an “open approach.”30 Spinetta’s31–35 work showed that children with fatal illnesses demonstrated an awareness of their impending death, whether told or not.

Complementing Spinetta’s work, Bluebond-Langner,36 an anthropologist, addressed the social and relational roots of the protective approach. In the early 1970s when her research on children with leukemia was conducted, most children died of the disease. Thus, the disease threatened the identities and personhood of clinicians who were trained to cure, parents whose role it was to protect their children, and the children who were destined to grow into adulthood. Cassel1,7 subsequently identified such a state as the essence of suffering. To address this kind of suffering, parents, clinicians, and children commonly adopted the practice of mutual pretense, a term introduced by Glaser and Strauss37 in studies of terminally ill adults and expanded on by Bluebond-Langner36 as it applied to children and their parents and clinicians.

Awareness of Suffering and the Rise of Pediatric Palliative Care

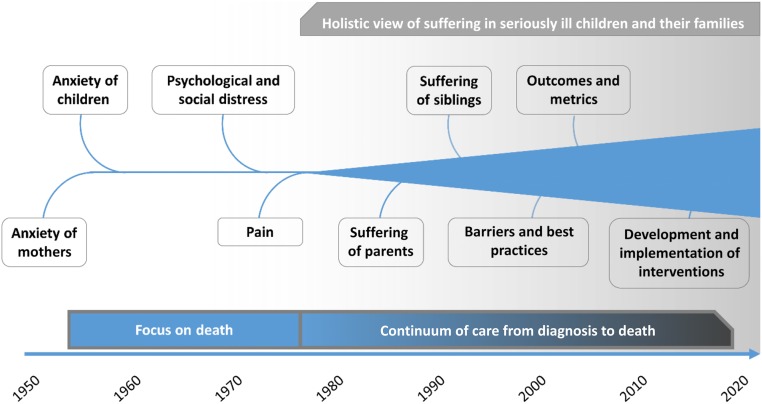

By the late 1970s, pediatrics was incorporating several concepts from adult hospice. Publications addressing suffering in children with serious illness proliferated. Several books expanded this discussion, promoting attention to psychological suffering,38 social challenges, best practices for orchestrating complex care, and a growing call for multidisciplinarity.4,39–42 Smith et al43 in 1979 described their approach to providing “total care” for children with cancer, noting the necessity of a broad team to meet the emotional, financial, and physical needs of the family. They also recommended a flattened hierarchy for team-based care: “All members of the cancer care team have an equal share in the total care of children so afflicted.”43 By 1983, Lewis44 argued that such principles should be applied to all seriously ill children as a continuum of care, not just those dying. At this time, most work on dying children was focused on cancer care, with limited attention to other life-limiting illnesses. Over time, clinicians more broadly applied palliative care principles to children with nononcologic diseases. Additionally, this philosophy called for care of the entire family, not just the child (Fig 1).45

FIGURE 1.

Timeline of concepts in pediatric palliative care literature.

Essentially, a more complete picture of the suffering of children was developing by the late 1970s, with a growing recognition of the need to address multiple domains of suffering simultaneously. Changes in the actual management of this suffering, however, lagged behind. Only 1 book published at this time, for example, addressed pain and symptoms of dying children; treatment recommendations were limited to 1 paragraph.46 This growing awareness of suffering in the face of unchanging clinical practice began to motivate small groups of like-minded individuals from different disciplines to improve this care.

Addressing these inadequacies, Chapman and Goodall47 published a detailed report of their care for a 9-year-old girl dying from sarcoma in 1980. Echoing the approach of Saunders, they argued for the anticipation of symptoms and modification of treatment approaches based on the disease trajectory. They also decried the state of the field: “For every child who dies, many more suffer. Both terminal care and symptom control in childhood have been neglected areas. . .As well as the physical symptoms, the emotional and spiritual needs of the child, the family, and the caring staff will all require attention.”47 They also called attention to the clinician’s role in exacerbating pain: “All those who care for sick and dying children should be acutely aware that blood tests and injections do hurt, that being intensively cared for can be frightening, and that intravenous drips may not allow parents to hold a dying child.”47

Symptom and pain control were based on experience and best guesses, allowing misperceptions about children’s pain to persist. It was common, for example, to perform lumbar punctures and bone marrow biopsies without sedation or analgesia. Some infants even underwent thoracotomy without analgesia because clinicians did not believe they experienced pain in a meaningful way.48 In 1977, 2 nurses named Eland and Anderson49 evaluated the number of analgesic doses prescribed for children versus adults after similar surgeries. Analgesics were ordered for 21 children, yet only 12 were given any. In contrast, 18 adults were prescribed a total of 372 opioid and 299 nonopioid pain doses.50 In 2 subsequent studies in 198351 and 1986,52 researchers found that children received less than half the analgesic doses given to adults after similar procedures. By the 1990s, this persistent discrimination sparked the framing of adequate pain management in children as an ethical issue.53

Despite these inadequacies, pediatrics was demonstrating a growing awareness of the need to address suffering. By the 1980s, pediatric textbooks began incorporating sections on the care of dying children.54 Before this, the only mention of childhood death in textbooks described technical procedures for handling the body after death.55 In 1977, the Pediatrician’s Manual included one of the first sections on this topic, a letter written by a dying child:

I am a 13-year-old boy. I am dying. I write this to you who are and will become nurses and doctors in the hope that, by sharing my feelings with you, you may someday be better able to help those who share my experience. But no one likes to talk about such things. . .The dying person is not yet seen as a person and thus cannot be communicated with as such. He is a symbol of what every human fears and what we each know. . .56

He ends his letter with a plea: “Don’t run away. Wait. All I want to know is that there will be someone to hold my hand when I need it. I’m afraid.”56

The pace of growth quickened by the late 1980s. In 1985, Corr and Corr57 edited a book that brought members of the hospice and pediatric communities together. In 1989, Papadatou and Papadatos,58 a Greek psychologist together with her pediatrician father, held the first international conference on children and death. Shortly after, Sourkes,59 a psychologist, published a book focused on the psychological experience of children with life-threatening illnesses. Furthermore, the first Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine in 1996 included a section on pediatric palliative care, affirming that it “was indeed a legitimate field of study related to, but different from, adult palliative care.”60 In that same year, the Journal of Palliative Care published a special thematic issue on pediatric palliative care that served as an important reference for the developing discipline.61

Although pediatric palliative care would eventually broaden to a continuum of care for all children with serious illnesses, early literature was focused primarily on the management of dying children. Beginning in 1978, Martinson et al’s62 work demonstrated the feasibility of children dying at home, if desired. Martinson was a nurse with a doctorate in physiology. Before this time, the hospital was the assumed place of death for most children. As noted by Martinson et al,62 “Neither dying at home nor home nursing care are new ideas. Indeed, they are old practices. Today, however, children with cancer are not typically offered the option of going home to die.” Her study showed that home care was feasible, cost-efficient, and did not harm parents, siblings, or the clinicians providing care. Subsequent work reaffirmed that home death was feasible and should be offered to families.63–68

In England, Sister Frances Dominica, a nurse and Anglican nun, recognized that some children could not be constantly cared for at home, with acute care hospitals providing the only alternative. This spurred the development of the first pediatric hospice in 1982: Helen’s House.69,70 From the beginning, the goals of pediatric hospice differed from adult hospice. Rather than serving primarily as a final place of death, “Most children admitted to Helen House came for some form of relief care either on a planned basis or to enable the family to cope with some crisis.”69 Of 52 children admitted during Helen’s House’s first year, only 8 received terminal care.

For hospitalized children, the approach to care also continued to evolve. In 1986, Goldman (a pediatric oncologist) developed the first multidisciplinary inpatient pediatric palliative care team:

This team does not confine itself to terminal care but, by choice, takes in supportive care at all stages of a child’s illness from diagnosis, during treatment, at relapse, terminally, and during bereavement. At all stages the care focuses on the management of physical symptoms, psychosocial support, and liaison within the community.71

From Aspiration to Practice: Palliative Care in Recent History

In contrast to the swelling aspirations for comprehensive, effective, and humane care of seriously ill children, evidence regarding actual practice was scant until the 21st century, when a series of studies showed that aspirations had not broadly translated into practice. In 2000, Wolfe et al72 interviewed 103 bereaved parents of children with cancer. Eighty-nine percent of these parents reported that their child suffered “a lot” or “a great deal” from symptoms like pain, fatigue, and dyspnea during their last month of life. Additionally, treatments for pain and dyspnea were successful only 27% and 16% of the time, respectively.72 In another study by Wolfe et al,73 physicians recognized that children with cancer would die 100 days sooner than parents did, highlighting deficiencies in communication with parents.73

The following year, Hilden et al74 surveyed pediatric oncologists about end-of-life care, finding “a strikingly high reliance on trial and error in learning to care for dying children, and a need for strong role models in this area.” In 2002, Contro et al75 explored bereaved families’ experiences with pediatric end-of-life care, uncovering “confusing, inadequate, or uncaring communications regarding treatment or prognosis; preventable oversights in procedures or policies; failure to include or meet the needs of siblings. . .and inconsistent bereavement follow-up.” Contro et al76 led another study in 2004, finding that “staff members reported feeling inexperienced in communicating with patients and families about end of life issues, transition to palliative care, and do-not-resuscitate status.”

In parallel, epidemiological and health service research studies began to demonstrate the diversity of complex chronic conditions that affected pediatric patients who died,77 with the implication that pediatric palliative care was appropriate not only for patients with cancer diagnoses or in the NICU setting but also for children and adolescents with severe cardiac, pulmonary, neurologic, or other conditions.78,79

National medical organizations began developing guidelines for the care of suffering and dying children. In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued its first explicit policy statement on pediatric palliative and end-of-life care, calling for “the development of clinical policies and minimum standards that promote the welfare of infants and children living with life-threatening or terminal conditions and their families, with the goal of providing equitable and effective support for curative, life-prolonging, and palliative care.”80 This policy proposed several principles of pediatric palliative care: respect for the dignity of patients and families, access to competent and compassionate palliative care, support for caregivers, improved professional and social support for pediatric palliative care, and continued improvement of pediatric palliative care through research and education. By 2008, the American Academy of Pediatrics had developed a provisional section for hospice and palliative medicine, which became permanent in 2010.

The Institute of Medicine, now called the National Academy of Science, Engineering, and Medicine, published a report on pediatric end-of-life care in 2003, noting that, “Too often, children with fatal or potentially fatal conditions and their families fail to receive competent, compassionate, and consistent care that meets their physical, emotional, and spiritual needs.”3 They recommended implementing institutional guidelines and policies, restructuring payments from the federal government, advancing interprofessional curricula to train palliative care specialists, and funding and developing a body of research to guide practice. They further noted the lack of empirical evidence: “Among the most common phrases in this report are ‘research is limited’ or ‘systematic data are not available.’”3 Subsequent research has begun to fill these gaps. In a follow-up report on dying in America in 2015, pediatric research was robust enough to be cited throughout the report, rather than being relegated to the “other” category, as in previous reports.45

Simultaneously, early training curricula for pediatric palliative care were being developed: the Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care in 200181 and End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium Pediatric Palliative Care in 2004.82 Shortly afterward, hospice and palliative medicine became an informal subspecialty in 2006, with formal recognition in 2008. Since this designation, pediatric palliative care has expanded in clinical practice, education, and research. By 2013, 69% of children’s hospitals surveyed reported having a palliative care team.83

As this field matures, investigators are examining the impact of primary and specialist pediatric palliative care. The PediQUEST trial, for example, has shown that supporting primary teams in providing palliative care to their patients can improve symptoms and quality of life.84 For complicated patients, mounting evidence demonstrates that specialist, multidisciplinary palliative care teams benefit patients and families.85–90 Yet, measuring and demonstrating value remains a persistent challenge.91,92

Successes, Challenges, and the Future

Over the last decade, clinical care and research in pediatric palliative care have advanced greatly. Most clinicians, for example, now view palliative care as critical to the care of all children with life-threatening illnesses,93 and most US pediatric hospitals have inpatient palliative care teams.83 Internationally, the World Health Organization has framed palliative care as an international human right to address global inequity in palliative care.94 In research, a growing body of evidence has defined the current state and standards for communication,95 psychosocial care,96 and symptom management,97 among others. Furthermore, studies such as the Promoting Resilience in Stress Management (PRISM) trial suggest a trend toward developing interventions.98 The amount and quality of research have increased rapidly in the last decade, far beyond the scope of what we can address in this article.99

Yet, challenges remain (Table 1). For example, palliative medicine is typically a consulting service, requiring the engagement of primary medical teams to maximize clinical impact. Quill and Abernethy100 promoted the concept of generalist and specialist palliative care in which palliative care principles are employed by all providers, and specialist palliative care is reserved for challenging scenarios. Some primary medical teams have resources and expertise to provide palliative care for most of their patients, whereas others have limited capabilities. The benefit of specialist palliative care consultation depends on these contextual factors. In certain specialties, however, clinician barriers might preclude involvement of palliative care teams, even if families would benefit from consultation. Furthermore, providing seamless care for children at the end of life remains a challenge as children transition from hospital to home or from hospital-based palliative care to community-based hospice or nursing services.

TABLE 1.

Remaining Challenges in PPC

| Remaining Challenges in PPC |

|---|

| Insufficient training, funding, and infrastructure to support the development of PPC investigators and academicians |

| Insufficient research funding |

| Deficiency of metrics to demonstrate productivity and quality of PPC |

| Need for validated outcome measures for PPC interventions |

| Disparities in access to PPC, especially outside the hospital |

| Variable integration of specialist PPC teams |

| Global disparities in access to PPC |

| Gaps in seamless care from hospital to community at the end of life |

PPC, pediatric palliative care.

In palliative care research, studies need to move beyond identifying problems and barriers, work that was crucial as the discipline was forming, and toward implementing the most effective clinical practices to minimize suffering. To achieve these research goals, this field must further develop infrastructure, training, and funding mechanisms to support the development of investigators.

Conclusions

The field of pediatric palliative care began a half century ago when small groups of individuals from diverse professional backgrounds became aware of the suffering of children and thought we could do better. Since then, these individual efforts have coalesced into a network of like-minded professionals dedicated to relieving the suffering of children with serious, life-limiting illnesses. This development has benefitted from the collaboration of nurses, social workers, anthropologists, physicians, psychologists, academics, advocates, and parents. Now, the passionate leaders who drove this initial development are handing the field over to the next generation. Building on this firm foundation, this next generation must address persistent challenges while also adapting to the changing realities of medicine, politics, and society.

Footnotes

Dr Sisk conceptualized the manuscript, performed a literature review, and drafted the initial manuscript; Drs Feudtner, Sourkes, Bluebond-Langner, Hinds, and Wolfe participated in conceptualizing and planning the review study, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported in part by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (award no. UL1 TR002345) (Dr Sisk). Additionally, Myra Bluebond-Langner’s post at University College London is funded by the True Colours Trust and supported by the National Institute for Health Research Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Cassel EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(11):639–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillier T. Diseases of Children: A Clinical Treatise Based on Lectures Delivered at the Hospital for Sick Children, London. London, United Kingdom: Bradbury, Evans, and Co; 1868 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Field MJ, Behrman RE; Institute of Medicine Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families . When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green M. Care of the dying child. Pediatrics. 1967;40(3):492–497 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong GL, Conn LA, Pinner RW. Trends in infectious disease mortality in the United States during the 20th century. JAMA. 1999;281(1):61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Olmsted RW. Care of the child with a fatal illness. J Pediatr. 1970;76(5):814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassel EJ. The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine, 2nd ed Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orbach CE, Sutherland AM, Bozeman MF. Psychological impact of cancer and its treatment. III. The adaptation of mothers to the threatened loss of their children through leukemia. II. Cancer. 1955;8(1):21–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bozeman MF, Orbach CE, Sutherland AM. Psychological impact of cancer and its treatment. III. The adaptation of mothers to the threatened loss of their children through leukemia. I. Cancer. 1955;8(1):1–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connor C. Hope and Healing: St. Louis Children’s Hospital, the First 125 Years. St Louis, MO: St. Louis Children’s Hospital; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blom GE. The reactions of hospitalized children to illness. Pediatrics. 1958;22(3):590–600 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman SB, Chodoff P, Mason JW, Hamburg DA. Behavioral observations on parents anticipating the death of a child. Pediatrics. 1963;32:610–625 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richmond JB, Waisman HA. Psychologic aspects of management of children with malignant diseases. AMA Am J Dis Child. 1955;89(1):42–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horwitz AV. How an age of anxiety became an age of depression. Milbank Q. 2010;88(1):112–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrissey J. Children’s adaptation to fatal illness. Soc Work. 1963;8(4):81–88 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yudkin S. Children and death. Lancet. 1967;1(7480):37–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toch R. Management of the child with a fatal disease. Clinical Pediatrics. 1964;3:418–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker EA., Jr Management of the child with a fatal disease. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1964;3:418–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solnit AJ, Green M. Psychologic considerations in the management of deaths on pediatric hospital services. I. The doctor and the child’s family. Pediatrics. 1959;24(1):106–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothenberg MB. Reactions of those who treat children with cancer. Pediatrics. 1967;40(3):507–510 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clark D. ‘Total pain’, disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958-1967. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(6):727–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rachels J. More Impertinent Distinctions and a Defense of Active Euthanasia In: Steinbock B, Norcross A, eds. Killing and Letting Die, 2nd ed New York, NY: Fordham University Press; 1994:ix [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark D. To Comfort Always: A History of Palliative Medicine since the Nineteenth Century, 1st ed Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saunders C, Summers DH, Teller N. Hospice: The Living Idea, 1st ed London, United Kingdom: Edward Arnold Ltd; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Billings JA. What is palliative care? J Palliat Med. 1998;1(1):73–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans AE, Edin S. If a child must die. N Engl J Med. 1968;278(3):138–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saunders C. The management of fatal illness in childhood. Proc R Soc Med. 1969;62(6):550–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore DC, Holton CP, Marten GW. Psychologic problems in the management of adolescents with malignancy. Experiences with 182 patients. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1969;8(8):464–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Howarth RV. The psychiatry of terminal illness in children. Proc R Soc Med. 1972;65(11):1039–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sisk BA, Bluebond-Langner M, Wiener L, Mack J, Wolfe J. Prognostic disclosures to children: a historical perspective. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20161278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spinetta JJ, Rigler D, Karon M. Anxiety in the dying child. Pediatrics. 1973;52(6):841–845 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spinetta JJ. The dying child’s awareness of death: a review. Psychol Bull. 1974;81(4):256–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spinetta JJ, Rigler D, Karon M. Personal space as a measure of a dying child’s sense of isolation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1974;42(6):751–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spinetta J, Maloney J. Death anxiety in the outpatient leukemic child. Pediatrics. 1975;56(6):1035–1037 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spinetta J. Adjustment in children with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 1977;2(2):49–51 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bluebond-Langner M. The Private Worlds of Dying Children. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1978 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Glaser BG. Awareness of Dying, 1st ed New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sourkes BM. The Deepening Shade: Psychological Aspects of Life-Threatening Illness. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press; 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Easson WM. The Dying Child; the Management of the Child or Adolescent Who Is Dying. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Pub Ltd; 1970 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Debuskey M, Dombro RH. The Chronically Ill Child and His Family. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Pub Ltd; 1970 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sahler OJZ. The Child and Death. St Louis, MO: Mosby; 1978 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adams DW. Childhood Malignancy: The Psychosocial Care of the Child and His Family. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Pub Ltd; 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith SD, Sturgeon JK, Rosen D, et al. Total care. Recent advances in the treatment of children with cancer. J Kans Med Soc. 1979;80(3):113–140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lewis IC. Humanizing paediatric care. Child Abuse Negl. 1983;7(4):413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues; Institute of Medicine . Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mennie AT. The Child in Pain In: Burton L, ed. Care of the Child Facing Death. London, United Kingdom, Boston, MA: Routledge and Kegan Paul; 1974:xi [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chapman JA, Goodall J. Helping a child to live whilst dying. Lancet. 1980;1(8171):753–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harrison H. Why infant surgery without anesthesia went unchallenged. New York Times. 1987. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1987/12/17/opinion/l-why-infant-surgery-without-anesthesia-went-unchallenged-832387.html. Accessed November 6, 2019

- 49.Eland JM, Anderson JE. The Experience of Pain in Children In: Jacox AK, ed. Pain: A Source Book for Nurses and Other Health Professionals. Boston, MA: Little, Brown; 1977 [Google Scholar]

- 50.McGrath PJ. Science is not enough: the modern history of pediatric pain. Pain. 2011;152(11):2457–2459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beyer JE, DeGood DE, Ashley LC, Russell GA. Patterns of postoperative analgesic use with adults and children following cardiac surgery. Pain. 1983;17(1):71–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schechter NL, Allen DA, Hanson K. Status of pediatric pain control: a comparison of hospital analgesic usage in children and adults. Pediatrics. 1986;77(1):11–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walco GA, Cassidy RC, Schechter NL. Pain, hurt, and harm. The ethics of pain control in infants and children. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(8):541–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.On children dying well. Lancet. 1983;1(8331):966–967 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Washington University School of Medicine. St Louis Children’s Hospital Records, 1879-2011. St Louis, MO: Washington University School of Medicine; Bernard Becker Medical Library Archives Sub-Series 3: Procedure books, 1947-1970, Box 127 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Collipp PJ. Pediatrician’s Manual. Oceanside, NY: Dabor Science Publications; 1977 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Corr CA, Corr DM. Hospice Approaches to Pediatric Care. New York, NY: Springer Pub Co; 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Papadatou D, Papadatos CJ. Children and Death. New York, NY: Hemisphere Pub Corp; 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sourkes BM. Armfuls of Time: The Psychological Experience of the Child With a Life-Threatening Illness. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davies B. Reflections on the Evolution of Palliative Care for Children. ChiPPS E-Journal. Alexandria, VA: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; 2018:8–15 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liben S. Pediatric palliative medicine: obstacles to overcome. J Palliat Care. 1996;12(3):24–28 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martinson IM, Amrstrong GD, Geis DP, et al. Home care for children dying of cancer. Pediatrics. 1978;62(1):106–113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martinson IM, Moldow DG, Armstrong GD, Henry WF, Nesbit ME, Kersey JH. Home care for children dying of cancer. Res Nurs Health. 1986;9(1):11–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moldow DG, Armstrong GD, Henry WF, Martinson IM. The cost of home care for dying children. Med Care. 1982;20(11):1154–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moldow DG, Martinson IM. From research to reality–home care for the dying child. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 1980;5(3):159–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lauer ME, Mulhern RK, Bohne JB, Camitta BM. Children’s perceptions of their sibling’s death at home or hospital: the precursors of differential adjustment. Cancer Nurs. 1985;8(1):21–27 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lauer ME, Mulhern RK, Wallskog JM, Camitta BM. A comparison study of parental adaptation following a child’s death at home or in the hospital. Pediatrics. 1983;71(1):107–112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lauer ME, Camitta BM. Home care for dying children: a nursing model. J Pediatr. 1980;97(6):1032–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burne SR, Dominica F, Baum JD. Helen House–a hospice for children: analysis of the first year. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1984;289(6459):1665–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Farrow G. Helen House: our first hospice for children. Nurs Times. 1981;77(33):1433–1434 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goldman A, Beardsmore S, Hunt J. Palliative care for children with cancer–home, hospital, or hospice? Arch Dis Child. 1990;65(6):641–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wolfe J, Klar N, Grier HE, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2469–2475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hilden JM, Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, et al. Attitudes and practices among pediatric oncologists regarding end-of-life care: results of the 1998 American Society of Clinical Oncology survey. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(1):205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen H. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Contro NA, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen HJ. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1248–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1, pt 2):205–209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ, Muldoon JH, Neff JM, Koepsell TD. Characteristics of deaths occurring in children’s hospitals: implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):887–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Feudtner C, Hays RM, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Neff JM, Koepsell TD. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/107/6/E99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2, pt 1):351–357 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Browning DM, Solomon MZ; Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care (IPPC) Investigator Team . The initiative for pediatric palliative care: an interdisciplinary educational approach for healthcare professionals. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20(5):326–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matzo ML, Sherman DW, Penn B, Ferrell BR. The end-of-life nursing education consortium (ELNEC) experience. Nurse Educ. 2003;28(6):266–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Feudtner C, Womer J, Augustin R, et al. Pediatric palliative care programs in children’s hospitals: a cross-sectional national survey. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1063–1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Cook EF, et al. Improving the care of children with advanced cancer by using an electronic patient-reported feedback intervention: results from the PediQUEST randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(11):1119–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, et al. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1717–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Friedrichsdorf SJ, Postier A, Dreyfus J, Osenga K, Sencer S, Wolfe J. Improved quality of life at end of life related to home-based palliative care in children with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(2):143–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kassam A, Skiadaresis J, Alexander S, Wolfe J. Differences in end-of-life communication for children with advanced cancer who were referred to a palliative care team. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(8):1409–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ananth P, Melvin P, Berry JG, Wolfe J. Trends in hospital utilization and costs among pediatric palliative care recipients. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(9):946–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ullrich CK, Lehmann L, London WB, et al. End-of-life care patterns associated with pediatric palliative care among children who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(6):1049–1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Snaman JM, Kaye EC, Lu JJ, Sykes A, Baker JN. Palliative care involvement is associated with less intensive end-of-life care in adolescent and young adult oncology patients. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(5):509–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kaye EC, Abramson ZR, Snaman JM, Friebert SE, Baker JN. Productivity in pediatric palliative care: measuring and monitoring an elusive metric. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):952–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Friedel M, Aujoulat I, Dubois AC, Degryse JM. Instruments to measure outcomes in pediatric palliative care: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2019;143(1):e20182379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Committee on Hospital Care Pediatric palliative care and hospice care commitments, guidelines, and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):966–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.World Health Organization. Palliative care. 2018. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care. Accessed July 15, 2019

- 95.Stein A, Dalton L, Rapa E, et al. ; Communication Expert Group . Communication with children and adolescents about the diagnosis of their own life-threatening condition. Lancet. 2019;393(10176):1150–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jones B, Currin-Mcculloch J, Pelletier W, Sardi-Brown V, Brown P, Wiener L. Psychosocial standards of care for children with cancer and their families: a national survey of pediatric oncology social workers. Soc Work Health Care. 2018;57(4):221–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Madden K, Magno Charone M, Mills S, et al. Systematic symptom reporting by pediatric palliative care patients with cancer: a preliminary report. J Palliat Med. 2019;22(8):894–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rosenberg AR, Bradford MC, McCauley E, et al. Promoting resilience in adolescents and young adults with cancer: results from the PRISM randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2018;124(19):3909–3917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Feudtner C, Rosenberg AR, Boss RD, et al. Challenges and priorities for pediatric palliative care research in the U.S. and similar practice settings: report from a pediatric palliative care research network workshop [published online ahead of print August 21, 2019]. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(5):909–917.e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Abernethy AP, Wheeler JL, Currow DC. Utility and use of palliative care screening tools in routine oncology practice. Cancer J. 2010;16(5):444–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]