Abstract

Purpose

Discontinuation of statin therapy represents a major challenge for effective cardiovascular disease prevention. It is unclear how often primary care physicians (PCPs) re-initiate statins and what barriers they encounter. We aimed to identify PCP perspectives on factors influencing statin re-initiation.

Methods

We conducted six nominal group discussions with 23 PCPs from the Deep South Continuing Medical Education network. PCPs answered questions about statin side effects, reasons their patients reported for discontinuing statins, how they respond when discontinuation is reported, and barriers they encounter in getting their patients to re-initiate statin therapy. Each group generated a list of responses in round-robin fashion. Then, each PCP independently ranked their top three responses to each question. For each PCP, the most important reason was given a weight of 3 votes, and the second and third most important reasons were given weights of 2 and 1, respectively. We categorized the individual responses into themes and determined the relative importance of each theme using a “percent of available votes” metric.

Results

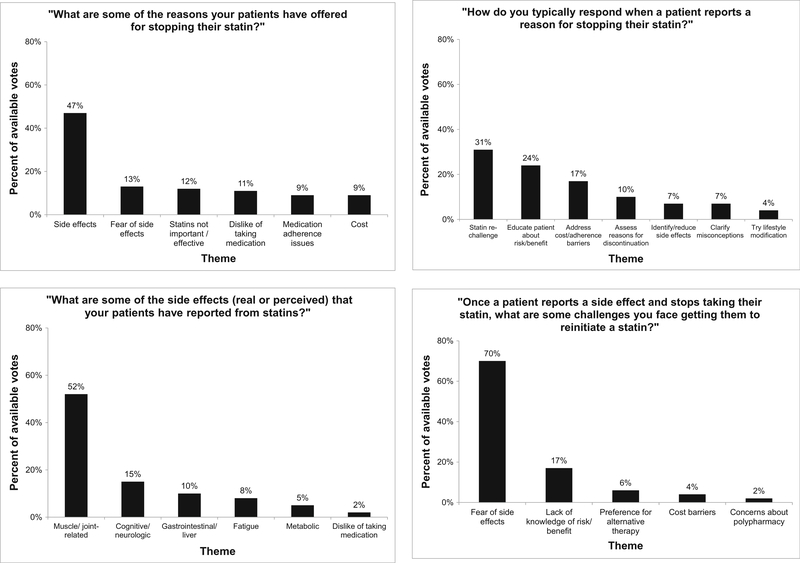

PCPs reported that side effects, especially muscle/joint-related symptoms, were the most common reason patients reported for statin discontinuation (47% of available votes). PCPs reported statin re-challenge as their most common response when a patient discontinues statin use (31% of available votes). Patients’ fear of side effects was ranked as the biggest challenge PCPs encounter in getting their patients to re-initiate statin therapy (70% of available votes).

Conclusion

PCPs face challenges getting their patients to re-initiate statins, particularly after a patient reports side effects.

Keywords: Qualitative research, Nominal groups, Statins, Side effects, Discontinuation, Re-challenge

Background

Statins are highly effective therapies for reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels and the risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) events [1, 2]. However, many people who initiate statins discontinue treatment due to side effects [3, 4]. Studies have demonstrated that many patients who discontinue treatment after experiencing symptoms such as muscle pain and weakness can be successfully re-challenged (i.e., re-started) on a statin and can continue therapy [4, 5]. There is some evidence that primary care physicians (PCPs) strongly endorse lipid management guidelines [6], but less is known about what actions they take when patients discontinue statin therapy.

The overall aim of this qualitative study was to understand the PCP perspective on statin side effects and reasons for statin discontinuation reported by their patients. We also investigated what actions PCPs say they undertake when their patients discontinue statins and the barriers they encounter in getting these patients to re-initiate treatment. Understanding PCP attitudes toward statin discontinuation and re-challenge is an essential foundational step in the development of effective strategies to increase the appropriate use of this therapy. To accomplish these aims, we conducted structured group discussions with a sample of PCPs.

Methods

We enrolled 23 PCPs from the Deep South Continuing Medical Education (CME) network, which includes approximately 1280 providers from 33 states. PCPs were recruited via e-mail and fax to participate in a semi-quantitative structured group process using the “nominal group technique” (NGT), for which they were offered a $200 honorarium. The NGT is a structured group discussion designed to elicit responses and prioritize them. This approach lends itself to research in problem identification, with advantages over other structured group process techniques such as focus groups. For example, the NGT prevents any one individual from monopolizing the discussion and allows for group cohesiveness, which is conducive to self-disclosure [7–9]. The NGT is particularly useful in identifying the dimensions of a healthcare issue [10], uncovering perspectives on barriers to providing optimal care [9, 11], and prioritizing root causes of a problem [12]. Furthermore, NGT sessions are easy to implement and produce easily interpretable results [7–9].

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, which waived the need for written informed consent. We conducted two NGT sessions, with each session lasting approximately 90 min and consisting of two questions. Session A (questions 1 and 2) addressed statin discontinuation, while Session B (questions 3 and 4) addressed statin side effects. The questions were developed through discussions among the investigators, including cardiologists, internists, and epidemiologists. PCPs were allowed to participate in one or both sessions. Each session was conducted three times, resulting in six discussion groups. The NGT sessions took place in a virtual meeting room, with PCPs calling in by phone while logged onto a website. All sessions were audiotaped.

After introductions, the facilitator stated the purpose of the study, and PCPs were presented with the first question and asked to silently generate a list of answers for 5 min. The group facilitator then solicited responses from each PCP in turn, generating a list visible to all participants via the website. Verbal exchange was limited to 1–2 sentences at a time, with the focus on understanding the meaning and logic of each item on the list. PCPs were encouraged to follow-up on others’ responses as a means of generating additional ideas. This process continued until all responses were exhausted. The PCPs were then asked to vote for the three most important or three most common items on the list, as appropriate. For each PCP, the most important, and second and third most important reasons were given weights of 3, 2, and 1 votes, respectively. Thus, each PCP had 6 total votes to contribute per question. Votes were summed and posted on the website as a prioritized list reflecting the group’s opinion about the most important responses to the question. These steps were repeated for each question. The first group to participate in Session B had some difficulty interpreting question 4, and therefore, the responses were not informative. We excluded this group of responses and worked with the NGT facilitator to develop a set of prompts to guide the subsequent groups. Following the NGT sessions, the participating PCPs were emailed a link to an online survey requesting their age, sex, race/ethnicity, medical specialty, any subspecialty training, and number of years in practice.

Data Analysis

We calculated means and ranges or counts and percentages for PCP demographic characteristics. For each question, we summed the individual weighted votes for each response and calculated a total score (e.g., if 4 PCPs ranked a response “most important” or “most common”, that response earned 12 votes). To make the data easier to interpret, we grouped the individual responses collected through the NGT sessions into themes, following the content analysis procedures outlined by A.D. van Breda in a manuscript on analyzing multiple-group NGT data [13]. Theme identification and categorization of the NGT responses was independently conducted by two researchers (RMT and PM), with any discrepancies resolved by a third researcher (RSR). We determined the relative importance of each theme across the three combined groups by summing the total votes for each response in the theme and dividing the sum by the number of available votes for the question. Data management and analysis were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2010.

Results

Demographics

Twenty of the 23 PCPs participating in the NGT sessions completed the demographic survey. The mean age was 50 years (range 29–74 years). Overall, 65% were men and 70% were white, 5% were African American, and 25% were Asian. PCPs reported being a general internist (55%) or family medicine physician (45%), with 20% reporting additional subspecialty training. On average, the PCPs had 16 years of experience in medical practice (range 1–47 years).

Session A (questions 1 and 2)

Session A consisted of 21 PCPs in three discussion groups—9 in group 1, 7 in group 2, and 5 in group 3—resulting in 126 total available votes for each question (Table 1). PCPs provided 23 responses to the question “Many individuals who are prescribed statins discontinue their medication for a variety of reasons. What are some of the reasons your patients have offered for stopping their statin?” (Supplemental Table 1, Panel A). Examples of responses included “muscle ache/weakness as a side effect,” “patients don’t understand how their disease affects them or the benefit of statins,” and “patients want to go off medicines and control cholesterol with diet.” We categorized the 23 responses into six themes: side effects, perception that statins are not important/not effective, fear of side effects, dislike of taking medication, medication adherence issues, and cost (Table 2, Panel A). Side effects were ranked as the most common reason PCPs reported their patients had offered for stopping their statin (47% of available votes; Fig. 1, top left panel).

Table 1.

Number of PCPs and available votes in each discussion group

| Session | Discussion group number | Number of PCPs | Number of available votes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question 1: “Many individuals who are prescribed statins discontinue their medication for a variety of reasons. What are some of the reasons your patients have offered for stopping their statin?” | |||

| A | 1 | 9 | 54 |

| A | 2 | 7 | 42 |

| A | 3 | 5 | 30 |

| Total | 21 | 126 | |

| Question 2:“How do you typically respond when a patient reports a reason for stopping their statin?” | |||

| A | 1 | 9 | 54 |

| A | 2 | 7 | 42 |

| A | 3 | 5 | 30 |

| Total | 21 | 126 | |

| Question 3: “What are some of the side effects (real or perceived) that your patients have reported from statins?” | |||

| B | 1 | 5 | 30 |

| B | 2 | 5 | 30 |

| B | 3 | 4 | 24 |

| Total | 14 | 84 | |

| Question 4: “Once a patient reports a side effect and stops taking their statin, what are some challenges you face getting them to re-initiate a statin?” | |||

| B | 1a | – | – |

| B | 2 | 5 | 30 |

| B | 3 | 4 | 24 |

| Total | 9 | 54 | |

The first group to participate in session B had difficulty interpreting question 4, and therefore, the responses were not informative and were excluded from the analysis.

PCP primary care physicians

Table 2.

Frequency of themes identified in the nominal group discussions

| Theme | Number of individual responses included in the theme† |

|---|---|

| Panel A | |

| Question 1: “Many individuals who are prescribed statins discontinue their medication for a variety of reasons.What are some of the reasons your patients have offered for stopping their statin?” | |

| Side effects | 8 |

| Statins not important/not effective | 5 |

| Fear of side effects | 4 |

| Dislike of taking medication | 2 |

| Medication adherence issues | 2 |

| Cost | 2 |

| Panel B | |

| Question 2: “How do you typically respond when a patient reports a reason for stopping their statin?” | |

| Re-challenge with another statin/lower dose | 4 |

| Educate patient about risk/benefit | 4 |

| Address cost/adherence barriers | 3 |

| Attempt to identify/reduce side effects | 3 |

| Assess reasons for discontinuation | 2 |

| Clarify misconceptions about side effects | 2 |

| Try lifestyle modification | 1 |

| Panel C | |

| Question 3: “What are some of the side effects (real or perceived) that your patients have reported from statins?” | |

| Muscle/joint-related symptoms | 3 |

| Cognitive/neurologic symptoms | 3 |

| Gastrointestinal/liver symptoms | 2 |

| Fatigue | 1 |

| Metabolic symptoms | 1 |

| Dislike taking medication | 1 |

| Panel D | |

| Question 4: “Once a patient reports a side effect and stops taking their statin, what are some challenges you face getting them to re-initiate a statin?” | |

| Fear of side effects | 6 |

| Lack of knowledge of risk/benefit | 4 |

| Preference for alternative therapy | 2 |

| Cost barriers | 1 |

| Concerns about polypharmacy | 1 |

Results in the table include all sessions pooled together

Refer to Supplemental Tables 1 and 2 for a list of the responses comprising each theme

Fig. 1.

Percent of available votes for each theme identified in the nominal group discussions. Results in the figure include all sessions pooled together

PCPs provided 19 responses to the question “How do you typically respond when a patient reports a reason for stopping their statin?” (Supplemental Table 1, Panel B). Examples of responses included “change the statin,” “use the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) risk calculator to show the patient their risk level,” and “discuss the reasons for stopping with the patient.” The responses were categorized into seven themes: re-challenge with another statin or lower dose of the same statin, educate patient about risk/benefit, address cost/adherence barriers, attempt to identify/reduce side effects, assess reasons for discontinuation, clarify misconceptions about side effects, and try lifestyle modification (Table 2, Panel B). Statin re-challenge was ranked as the most important PCP response when a patient reports a reason for statin discontinuation, followed by educating the patient about risk/benefit, and addressing cost/adherence barriers (31, 24, and 17% of available votes, respectively; Fig. 1, top right panel).

Session B (questions 3 and 4)

Session B consisted of 14 PCPs in three discussion groups—5 in group 1, 5 in group 2, and 4 in group 3—resulting in a maximum of 84 total available votes (Table 1). Votes from all PCPs were considered informative and included in the analysis for question 3. As discussed above, 30 votes from PCPs in group 1 were considered non-informative and excluded from the analysis for question 4, resulting in a total of 54 available votes for this question. PCPs provided 11 responses to the question “What are some of the side effects (real or perceived) that your patients have reported from statins?” (Supplemental Table 2, Panel A). Examples of responses included “muscle pain,” “joint ache,” “mental confusion or ‘fogginess,” and “gastrointestinal upset including gas, constipation, nausea, and diarrhea.” We categorized the side effects into six themes: muscle/joint-related symptoms, cognitive/neurologic symptoms, gastrointestinal/liver symptoms, fatigue, metabolic symptoms, and dislike of taking medication (Table 2, Panel C). Muscle/joint-related symptoms were ranked as the most common side effects patients report from statins (52% of available votes; Fig. 1, bottom left panel).

PCPs identified 14 responses to the question “Once a patient reports a side effect and stops taking their statin, what are some challenges you face getting them to re-initiate a statin?” (Supplemental Table 2, Panel B). Examples of responses included “patients are fearful of a recurrent issue with another statin or one that has demonstrated harm,” “patients express concern about experiencing muscle pain,” and “patients don’t feel bad, so they don’t understand why they need to take a statin.” The responses were categorized into five themes: fear of side effects, lack of knowledge of CVD risk/statin benefits, preference for alternative therapy, cost barriers, and concerns about polypharmacy (Table 2, Panel D). Patient fear of side effects was ranked as the biggest challenge PCPs face getting patients to re-initiate statin therapy (70% of available votes; Fig. 1, bottom right panel).

Discussion

This qualitative study identified PCP perspectives on statin side effects reported by their patients, reasons their patients report for discontinuing their statin, typical PCP responses when a patient reports discontinuing their statin, and the barriers PCPs encounter in getting their patients to re-initiate treatment following discontinuation. Side effects, most often muscle/joint-related symptoms, were the most common reason PCPs reported their patients stopped taking their statin. PCPs identified statin re-challenge as their most common response when a patient discontinued their statin. Patients’ fear of side effects was ranked as the biggest challenge PCPs face getting patients to re-initiate statin therapy after discontinuation.

Despite the benefits of statin therapy for primary and secondary prevention [1, 2, 14–16], many patients who initiate statins discontinue therapy. In the USAGE study, a self-administered internet-based survey of 10,183 adults with hypercholesterolemia, 12% of participants reported having discontinued statin therapy [17]. Former statin users cited muscle pain as the primary reason for discontinuation (60%), followed by cost (16%), and perceived lack of efficacy (13%) [17]. Participants <55 years of age and those without health insurance, who underwent annual cholesterol monitoring, and used the internet to learn about statin treatment were more likely to discontinue statin therapy, while participants with a higher annual household income and those who were satisfied with their statin medication and were taking a concomitant medication for diabetes, hypertension, or a psychiatric condition were less likely to discontinue their statin [17]. There was an increased risk of statin discontinuation associated with experiencing side effects, especially among those who reported experiencing muscle-related side effects while taking a statin [17].

Statin therapy has been associated with multiple side effects. According to a recent meta-analysis, statin-associated muscle symptoms are the most common side effect, affecting 10–25% of patients receiving therapy [18]. Statin-associated muscle symptoms range from myalgia to clinical rhabdomyolysis in rare cases [19]. In a systematic review of 26 clinical trials, 12.7% of participants on statin therapy developed myalgia [20]. In GAUSS-3, a randomized controlled trial of adults with a history of statin intolerance, 42.6% of participants reported intolerable muscle-related symptoms while taking atorvastatin, while 26.5% reported these symptoms while taking placebo [21]. These data suggest that not all muscle-related symptoms that are reported by people taking statins may be attributable to this therapy [20]. In a web-based survey, 59% of 722 participants with statin-associated side effects self-reported cognitive problems [18, 22]. However, larger cross-sectional studies have failed to find an association between statin use and cognitive function, suggesting that if these symptoms are true side effects, they may be rare [18]. Results of prospective studies and randomized controlled trials show conflicting evidence of an effect of statins on cognition, and a recent review of the literature concluded that there was a moderate level of evidence of neither harm nor benefit of statins on memory [23, 24]. Statins are frequently associated with increases in liver function tests, especially in the first 12 weeks of treatment, but liver disease attributable to statins is rare [25, 26].

PCPs participating in the current study reported side effects as a frequent reason patients discontinued statin use, and the most commonly reported side effects were muscle/joint-related. Consistent with the patient-centered findings of the USAGE study [17], in the current study PCPs reported that perceived lack of statin efficacy was one of the most frequent reasons that patients discontinued statin therapy. Although the USAGE study reported cost as a common reason patients discontinue statin therapy [17], PCPs identified cost as a less important reason for statin discontinuation in the current study. The current study extends prior research by providing a PCP perspective on commonly reported statin side effects, reasons patients report for discontinuation of statin therapy, and the barriers PCPs encounter in getting their patients to re-initiate treatment following discontinuation.

Studies have demonstrated that many people who discontinue statin therapy due to side effects can be successfully re-challenged and continue therapy [4, 5]. For example, in a study by Zhang et al., of over 100,000 patients taking a statin and receiving routine outpatient care, 10% discontinued therapy due to a “statin-related event” (most commonly myalgia/myopathy). Most patients who discontinued therapy were re-challenged, and among those re-challenged, more than one-third were taking the same statin at the same or a higher dose at 12 months after the statin-related event [4]. These data suggest that many patients who are re-challenged can tolerate longterm statin use despite the presence of initial symptoms [4].

In the current study, PCPs reported statin re-challenge as their most common approach when a patient reports discontinuing their statin. Individual re-challenge strategies reported by PCPs included treating the patient with a different statin type and reducing the statin dose. In a 2013 clinic-based study, Mampuya et al. compared treatment strategies for patients referred for statin intolerance with a focus on intermittent statin dosing, defined as a statin prescription that is not taken on a daily basis [5]. Over 70% of patients with prior statin intolerance were able to tolerate a statin over a median follow-up of 31 months [5]. Most (63%) of these patients were on a daily statin regimen, and 9% were on an intermittent dosing regimen [5]. Patients on intermittent statin dosing had a smaller LDL-C reduction compared to the daily dosing group, but a larger LDL-C reduction compared to those who discontinued statin therapy [5]. Also, compared to those who discontinued statin therapy, a higher proportion of intermittent statin users achieved their LDL-C goal [5]. These findings suggest that intermittent statin dosing can be an effective therapeutic option among patients with prior statin intolerance who cannot tolerate re-challenge with daily statin dosing.

The current study has several strengths, including a diverse sample of physicians and the assessment of four domains related to statin side effects and treatment discontinuation. Despite these strengths, the findings of the current study should be considered in the context of known and potential limitations. We enrolled a convenience sample of 23 PCPs, and the generalizability of this sample is unclear. Although our sample size is small, it is consistent with other qualitative studies. For example, a recent qualitative study of factors impacting HIV care adherence identified barriers and facilitators to clinic visit and medication adherence among 18 HIV-infected women [27]. A separate study of barriers and facilitators to use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain recruited 26 patients, 14 nurses, and 12 PCPs for participation in nominal groups [28]. Also, the consistency of responses between the NGT groups suggests that their opinions may reflect those of similar PCPs. We restricted study participation to PCPs, and it is possible that other healthcare providers (e.g., cardiologists) would generate different responses if asked the same questions. While other perspectives are important, hypercholesterolemia management is performed mostly by PCPs in the USA [7].

In conclusion, this study identified PCP perspectives on reasons for statin discontinuation, their responses when patients discontinue statin therapy, commonly reported side effects, and perceived challenges to statin re-initiation. Statin side effects constituted an important contributor to statin discontinuation and barrier to re-initiation. Results from the current study may be used to inform the development of an intervention to enhance the optimal use of statin therapy in primary care. Strategies are needed to minimize statin discontinuation and to enhance statin re-initiation when discontinuation occurs in an effort to reduce the risk of CVD events.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The design and conduct of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, and preparation of the manuscript were supported through a research grant from Amgen, Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA). The academic authors conducted all analyses and maintained the rights to publish this article.

Compliance with Ethical Standards This study was funded by a research grant from Amgen, Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA). RMT, RO, MM, and LDC declare that they have no conflicts of interest. MMS has received research support from and served on an advisory board for Amgen, Inc. KLM and BT are employees and stockholders of Amgen, Inc. RD is an employee of Esperion Therapeutics and was an employee and stockholder of Amgen, Inc. at the time of this study. PM has received research support and honoraria from Amgen, Inc. RSR has received research grants from Akcea, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Esperion, and Medicines Company; honoraria from Kowa; royalties from UpToDate, Inc.; and has served as a consultant or on advisory boards for Akcea, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Regeneron, and Sanofi Aventis. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, which waived the need for written informed consent.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10557-017-6738-x) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Taylor F, Ward K, Moore TH, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;1:CD004816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1267–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Ito MK, Jacobson TA. Understanding Statin Use in America and Gaps in Patient Education (USAGE): an internet-based survey of 10,138 current and former statin users. J Clin Lipidol. 2012;6(3):208–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(7): 526–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mampuya WM, Frid D, Rocco M, et al. Treatment strategies in patients with statin intolerance: the Cleveland Clinic experience. Am Heart J. 2013;166(3):597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eaton CB, Galliher JM, McBride PE, Bonham AJ, Kappus JA, Hickner J. Family physician’s knowledge, beliefs, and self-reported practice patterns regarding hyperlipidemia: a National Research Network (NRN) survey. JABFM. 2006;19(1):46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safford MM, Shewchuk R, Qu H, et al. Reasons for not intensifying medications: differentiating “clinical inertia” from appropriate care. J Gen Int Med. 2007;22(12):1648–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shewchuk R, O’Connor SJ. Using cognitive concept mapping to understand what health care means to the elderly: an illustrative approach for planning and marketing. Health Mark Q. 2002;20(2):69–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine DA, Saag KG, Casebeer LL, Colon-Emeric C, Lyles KW, Shewchuk RM. Using a modified nominal group technique to elicit director of nursing input for an osteoporosis intervention. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2006;7(7):420–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van de Ven AH, Delbecq AL. The nominal group as a research instrument for exploratory health studies. Am J Public Health. 1972;62(3):337–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hickling JA, Nazareth I, Rogers S. The barriers to effective management of heart failure in general practice. Brit J Gen Pract. 2001;51(469):615–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delbecq AL, Van de Ven AH. A group process model for problem identification and program planning. J Appl Behav Sci. 1971;7(4) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Breda A Steps to analysing multiple-group NGT data. Soc Work Pract Res. 2005;17(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byington RP, Furberg CD, Crouse JR 3rd, Espeland MA, Bond MG. Pravastatin, lipids, and atherosclerosis in the carotid arteries (PLAC-II). Am J Cardiol. 1995;76(9):54C–9C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohsfeldt RL, Gandhi SK, Smolen LJ, et al. Cost effectiveness of rosuvastatin in patients at risk of cardiovascular disease based on findings from the JUPITER trial. J Med Econ. 2010;13(3):428–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramsey SD, Clarke LD, Roberts CS, Sullivan SD, Johnson SJ, Liu LZ. An economic evaluation of atorvastatin for primary prevention of cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes. Pharmaco Economics. 2008;26(4):329–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei MY, Ito MK, Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA. Predictors of statin adherence, switching, and discontinuation in the USAGE survey: understanding the use of statins in America and gaps in patient education. J Clin Lipidol. 2013;7(5):472–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson PD, Panza G, Zaleski A, Taylor B. Statin-associated side effects. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(20):2395–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenson RS, Baker SK, Jacobson TA, Kopecky SL, Parker BA. The National Lipid Association’s Muscle Safety Expert Panel: an assessment by the statin muscle safety task force: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8(3 Suppl):S58–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganga HV, Slim HB, Thompson PD. A systematic review of statin-induced muscle problems in clinical trials. Am Heart J. 2014;168(1):6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nissen SE, Stroes E, Dent-Acosta RE, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of evolocumab vs ezetimibe in patients with muscle-related statin intolerance: the GAUSS-3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1580–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans WJ, Cannon JG. The metabolic effects of exercise-induced muscle damage. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1991;19:99–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rojas-Fernandez C, Hudani Z, Bittner V. Statins and cognitive side effects: what cardiologists need to know. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2016;45(1):101–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samaras K, Brodaty H, Sachdev PS. Does statin use cause memory decline in the elderly? Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2016;26(6):550–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Denus S, Spinler SA, Miller K, Peterson AM. Statins and liver toxicity: a meta-analysis. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24(5):584–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Calderon RM, Cubeddu LX, Goldberg RB, Schiff ER. Statins in the treatment of dyslipidemia in the presence of elevated liver aminotransferase levels: a therapeutic dilemma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(4):349–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boehme AK, Davies SL, Moneyham L, Shrestha S, Schumacher J, Kempf MC. A qualitative study on factors impacting HIV care adherence among postpartum HIV-infected women in the rural southeastern USA. AIDS Care. 2014;26(5):574–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becker WC, Dorflinger L, Edmond SN, Islam L, Heapy AA, Fraenkel L. Barriers and facilitators to use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain. BMC Fam Pract. 2017;18(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.