Abstract

BACKGROUND

Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (MDRAB) has emerged as an increasingly important pathogen that causes nosocomial meningitis. However, MDRAB-associated nosocomial meningitis is rarely reported in children.

CASE SUMMARY

We report the case of a 1-year-old girl with a choroid plexus papilloma, who developed postoperative nosocomial meningitis due to MDRAB. The bacterial strain was sensitive only to tigecycline and colistin, and showed varying degrees of resistance to penicillin, amikacin, ceftriaxone, cefixime, cefotaxime, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, gentamicin, meropenem, imipenem, and tobramycin. She was cured with intravenous doxycycline and intraventricular gentamicin treatment.

CONCLUSION

Doxycycline and gentamicin were shown to be effective and safe in the treatment of a pediatric case of MDRAB meningitis.

Keywords: Acinetobacter baumannii, Meningitis, Doxycycline, Gentamicin, Multidrug resistance, Case report

Core tip: Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (MDRAB) is a troublesome pathogen owing to multidrug resistance. Postoperative nosocomial meningitis due to Acinetobacter baumannii is rarely reported in children. Nosocomial meningitis due to MDRAB is fatal and its treatment is challenging because of the low blood-brain barrier permeability of antibiotic drugs. We describe the case of a child who developed post-neurosurgical meningitis due to MDRAB that was effectively treated by the combination of intravenous doxycycline and intraventricular gentamicin administration.

INTRODUCTION

Acinetobacter baumannii (A. baumannii) is a Gram-negative bacterium that causes various nosocomial infections[1,2]. Postoperative nosocomial meningitis due to A. baumannii is rarely reported in children. Treatment of A. baumannii infection is of concern due to the increasing prevalence of multidrug resistance[3]. In this report, we present the case of a child who developed post-neurosurgical meningitis due to multidrug-resistant A. baumannii (MDRAB). The child was successfully treated with intravenous doxycycline and intraventricular gentamicin administration. This report also presents a systematic literature review concerning MDRAB-associated nosocomial meningitis in children.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 1-year-old girl with head trauma was admitted to our hospital in November 2016. At four weeks after surgery, the patient was febrile and disturbance of consciousness was observed.

History of present illness

The patient fell off the bed and mild head trauma was suspected. Incidentally, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head revealed an intracranial space-occupying lesion (Figure 1A). One week after the admission, the child underwent a brain tumor resection. Immunohistochemical staining of the specimens indicated a choroid plexus papilloma. On the fourth postoperative week, she suddenly developed an altered state of consciousness with febrile illness. External ventricular drainage was performed. During the course of the disease, the patient had no diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, cold, or any other discomfort.

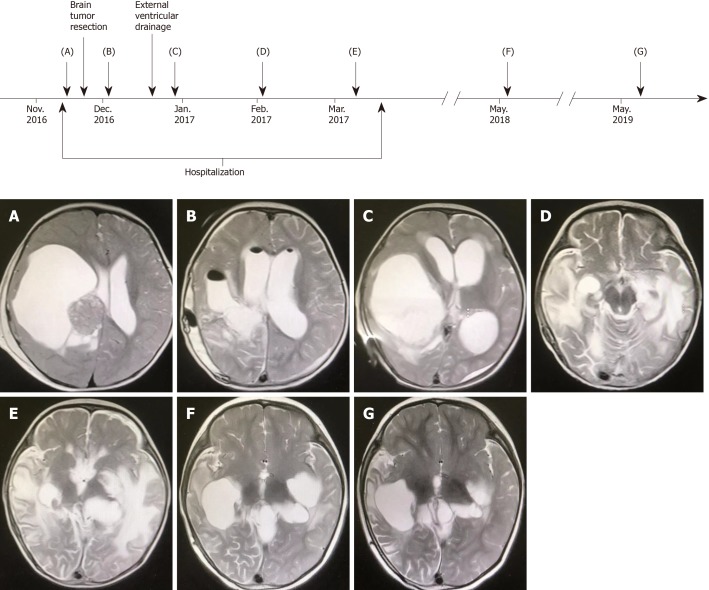

Figure 1.

Computed tomography images. A: Computed tomography (CT) showed an intracranial space-occupying lesion; B-G: CT examination results during patient follow-up.

History of past illness

The patient had no medical history of chronic diseases such as diabetes, coronary and other heart diseases, infectious diseases such as hepatitis and tuberculosis, surgery, blood transfusion, trauma, and drug allergy. The patient’s history of preventive inoculation was unknown.

Personal and family history

She was operated for a choroid plexus papilloma in November 2016. The rest of the personal and family history was unexceptional.

Physical examination upon admission

At admission, the patient showed stable vital signs; however, the skin on the right side of the forehead was swollen, approximately 5.5 cm × 4 cm in size. On the fourth postoperative week, she suddenly developed an altered state of consciousness and hypertonia of limbs, along with the disappearance of the direct and indirect pupillary light reflexes.

Laboratory examinations

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination showed a white blood cell count of 500/mm3. The patient was diagnosed with meningitis and intravenous administrations of meropenem (120 mg/kg/d divided q8h) and vancomycin (60 mg/kg/d divided q6h) were initiated; however, the patient did not show any improvement. After 5 d, CSF analysis showed a white blood cell count of 40000/mm3, protein concentration of 573 mg/dL, and glucose concentration of 0 mmol/L. CSF culture was positive for A. baumannii, which was sensitive only to tigecycline and colistin while it showed varying degrees of resistance to penicillin, amikacin, ceftriaxone, cefixime, cefotaxime, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, gentamicin, meropenem, imipenem, and tobramycin.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Postoperative MDRAB meningitis.

TREATMENT

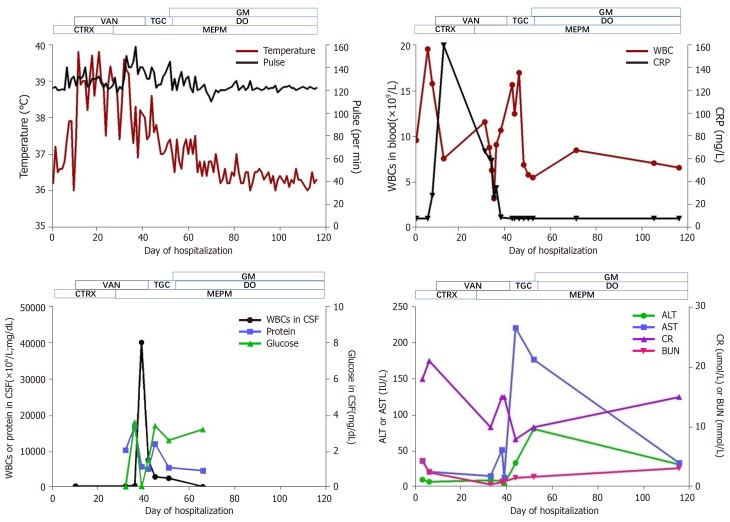

As colistin has severe side effects in children, the patient was started on tigecycline (2 mg/kg/d divided q12h). After 12 d of antibiotic therapy with tigecycline, the patient still had a fever. The CSF culture was positive for MDRAB. Doxycycline is known to be active against MDRAB and was administered to the patient following the failure of tigecycline (4 mg/kg/d divided q12h) and intraventricular gentamicin (2 mg/d, once daily) was administered. The patient became afebrile 6 d later. After 17 d, the CSF was found to be sterile. Doxycycline and gentamicin were administered for 8 wk. The clinical course of the patient is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Clinical course of a 1-year-old patient with multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii meningitis. CTRX: Ceftriaxone (Rocephin); MEPM: Meropenem; VAN: Vancomycin; TGC: Tigecycline; DO: Doxycycline; GM: Gentamicin; WBC: White blood cell; CRP: C-reactive protein; CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; BUN: Blood urea nitrogen; Cr: Creatinine.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

There were no serious side effects of doxycycline and gentamicin treatment. The patient is now healthy and is receiving scheduled follow-up and her CT examination results remained normal at the subsequent two-year follow-up (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

MDRAB is a troublesome pathogen in healthcare institutions owing to multidrug resistance, which is a threat to the current antibiotic era[4]. Nosocomial meningitis due to MDRAB is fatal and its treatment is challenging because of the low blood-brain barrier permeability of antibiotic drugs[5,6]. Thus, the choice of antibiotics is critical to the treatment of nosocomial MDRAB meningitis. It is also important to analyze the blood and CSF cultures before treatment initiation to avoid inappropriate antibiotic use. In the present case, CSF culture showed the presence of MDRAB that was sensitive only to tigecycline and colistin.

In the past, colistin had been used successfully against Gram-negative bacteria; however, its prescription decreased due to nephrotoxicity[7]. Tigecycline is a broad-spectrum bacteriostatic compound of glycylcyclines, which is active against several multidrug-resistant pathogens as well as MDRAB[8]. In our case, tigecycline was initially administered intravenously, but the patient did not respond to the treatment and continued to manifest typical signs of meningitis. The possible explanation of the therapeutic failure of intravenous tigecycline treatment could be attributed to its poor ability to penetrate through the blood-brain barrier. Thus, a combination of intravenous and intraventricular (IVT) antibiotic administration may be a therapeutic option to ensure sterilization of the CSF. Both doxycycline and tigecycline belong to the tetracycline class of antibiotics. Doxycycline was administered following the failure of tigecycline, known to be active against MDRAB. In our case, doxycycline was effective in the treatment of the CNS infection, which may be explained by an increased doxycycline distribution in the CNS owing to the disruption of the blood-brain barrier, in inflammatory diseases like meningitis. However, further pharmacological studies are needed to confirm this observation. Moreover, the intraventricular gentamicin administration could effectively sterilize the CSF.

MDRAB has emerged as an increasingly important pathogen often associated with post-neurosurgical meningitis[9]. In the literature, the number of pediatric cases with MDRAB meningitis is low. Data regarding the clinical characteristics, therapy, and treatment outcomes in pediatric cases are summarized in Table 1[10-15]. Since active antibiotics including tigecycline and colistin diffuse poorly to the central nervous system, it is a challenge to treat patients via intravenous administration of these drugs. The IVT administration of these antibiotics is currently the only treatment option for MDRAB meningitis.

Table 1.

Clinical features of the reported series of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii meningitis in children

| Ref. | Age (yr) | Sex | Acinetobacter susceptibility | Final regimen(s) | Toxicity | Treatment outcome |

| Kaplan et al[10] | 4 | NR | Multidrug resistant | Cefotaxime and aminoglycoside IV, and colistin IVR | None | Cure |

| Ng et al[11] | 4 | Male | Multidrug resistant | Amikacin and colistin IV, and colistin IT | Chemical meningitis | Cure |

| Ozdemir et al[12] | 3 | Female | Colistin | Colistin and ampicillin–sulbactam IV, and colistin IT | None | Cure |

| 14 | Female | Colistin | Meropenem and ampicillin–sulbactam IV, and rifampin PO | None | Cure | |

| 1 | Male | Colistin | Colistin and meropenem IV | None | Cure | |

| Lee et al[13] | 3 | Male | Imipenem | Colistin IV | None | Cure |

| Ganjeifar et al[14] | 6 | Male | Doxycycline and rifampin | Colistin and rifampin IV, and colistin IVR | NR | Cure |

| Jiménez-Mejías et al[15] | 14 | Male | Colistin | Colistin IV | None | Cure |

IT: Intrathecal; IV: Intravenous; IVR: Intraventricular; PO: Peroral; NR: Not reported.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this case suggests that the combination of intravenous doxycycline and intraventricular gentamicin administration may be a potentially effective and safe therapeutic option for the treatment of childhood MDRAB meningitis.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: The patient’s family members provided written informed consent.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: September 18, 2019

First decision: October 24, 2019

Article in press: November 23, 2019

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cure E, Schwan WR, Yellanthoor RB S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Wu YXJ

Contributor Information

Xia Wu, Department of Infectious Diseases, Children’s Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai 201102, China.

Lu Wang, Department of General Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai 201102, China.

Ying-Zi Ye, Department of Infectious Diseases, Children’s Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai 201102, China.

Hui Yu, Department of Infectious Diseases, Children’s Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai 201102, China. yuhui4756@sina.com.

References

- 1.Munoz-Price LS, Weinstein RA. Acinetobacter infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1271–1281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergogne-Bérézin E, Towner KJ. Acinetobacter spp. as nosocomial pathogens: microbiological, clinical, and epidemiological features. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:148–165. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peleg AY, Seifert H, Paterson DL. Acinetobacter baumannii: emergence of a successful pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:538–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim BN, Peleg AY, Lodise TP, Lipman J, Li J, Nation R, Paterson DL. Management of meningitis due to antibiotic-resistant Acinetobacter species. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:245–255. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70055-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain R, Danziger LH. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter infections: an emerging challenge to clinicians. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:1449–1459. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levin AS, Barone AA, Penço J, Santos MV, Marinho IS, Arruda EA, Manrique EI, Costa SF. Intravenous colistin as therapy for nosocomial infections caused by multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;28:1008–1011. doi: 10.1086/514732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karageorgopoulos DE, Falagas ME. Current control and treatment of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:751–762. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70279-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pankey GA. Tigecycline. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:470–480. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giamarellou H, Antoniadou A, Kanellakopoulou K. Acinetobacter baumannii: a universal threat to public health? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan SL, Patrick CC. Cefotaxime and aminoglycoside treatment of meningitis caused by gram-negative enteric organisms. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:810–814. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199011000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng J, Gosbell IB, Kelly JA, Boyle MJ, Ferguson JK. Cure of multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii central nervous system infections with intraventricular or intrathecal colistin: case series and literature review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:1078–1081. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ozdemir H, Tapisiz A, Ciftçi E, Ince E, Mokhtari H, Güriz H, Aysev AD, Doğru U. Successful treatment of three children with post-neurosurgical multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii meningitis. Infection. 2010;38:241–244. doi: 10.1007/s15010-010-0018-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SY, Lee JW, Jeong DC, Chung SY, Chung DS, Kang JH. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter meningitis in a 3-year-old boy treated with i.v. colistin. Pediatr Int. 2008;50:584–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2008.02677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganjeifar B, Zabihyan S, Baharvahdat H, Baradaran A. Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ventriculitis: a serious clinical challenge for neurosurgeons. Br J Neurosurg. 2016;30:589–590. doi: 10.1080/02688697.2016.1206183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiménez-Mejías ME, Pichardo-Guerrero C, Márquez-Rivas FJ, Martín-Lozano D, Prados T, Pachón J. Cerebrospinal fluid penetration and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic parameters of intravenously administered colistin in a case of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii meningitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;21:212–214. doi: 10.1007/s10096-001-0680-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]