Abstract

Objective:

Characterize the early trajectories of financial functioning in adults with history of childhood ADHD and use these trajectories to project earnings and savings over the lifetime.

Method:

Data were drawn from a prospective case-control study (PALS) following participants with a rigorous diagnosis of ADHD during childhood (N=364) and demographically-matched controls (N=240) for nearly 20 years. Participants and their parents reported on an array of financial outcomes when participants were 25 and 30 years old.

Results:

At age 30, adults with a history of ADHD exhibited substantially worse outcomes than controls on most financial indicators, even when they and their parents no longer endorsed any DSM symptoms of ADHD. Between ages 25 and 30, probands had exhibited considerably slower growth than controls in positive financial indicators (e.g., monthly income) and substantially less reduction than controls in indicators of financial dependence (e.g., living with parents), indicating worsening or sustained deficits on nearly all measures. When earnings trajectories from age 25 to age 30 were extrapolated using matched Census data, male probands were projected to earn $1.27m less than controls over their working lifetime, reaching retirement with up to 75% lower net worth.

Conclusion:

The financial deficit of adults with history of childhood ADHD grows across early adulthood. Projections based on early financial trajectories suggest very large cumulative differences in earnings and savings. With or without persistence of the DSM symptoms, the adult sequela of childhood ADHD can be conceptualized as a chronic condition often requiring considerable support from others during adulthood.

Keywords: ADHD, impairment, personal finance

Introduction

Approximately 10% of children in the United States (Danielson et al., 2018) have been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), a diagnosis characterized by inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity. A growing literature has shown that children diagnosed with ADHD experience a variety of difficulties in adulthood (Barkley, Murphy, & Fischer, 2008), with most studies focusing on diagnostic symptomatology (Sibley et al., 2012), substance use (Molina & Pelham, 2014), and educational and occupational functioning (Barkley, Fischer, Smallish, & Fletcher, 2006; Kuriyan et al., 2013). Fewer studies have reported on financial functioning, even though financial independence might be considered the primary developmental goal of adulthood, just as school completion might be considered the primary developmental goal of childhood and adolescence. The literature to date suggests that adults who were diagnosed with ADHD during childhood report lower income (Hechtman et al., 2016; Klein et al., 2012), have less in savings (Barkley et al., 2008), and are more likely to receive public assistance (E. B. Owens, Zalecki, Gillette, & Hinshaw, 2017) or be financially dependent on parents (Altszuler et al., 2016; Biederman et al., 2012). Thus, poor finances may be one of the most critical and impairing deficits for adults with a history of ADHD, their parents, and their spouses.

This emergent literature has several limitations. First, all previous studies have examined financial functioning at a single point in time, leaving it unknown how ADHD-related deficits evolve over the course of adulthood. On one hand, the gap may shrink as those with ADHD eventually “catch up” to controls in financial status, consistent with a conceptualization of ADHD as a developmental delay that slows progression through important milestones but is eventually overcome. On the other hand, the gap may persist or even grow, consistent with a conceptualization of ADHD as a chronic, refractory disorder that confers lasting and potentially cumulative impairment.

Second, no previous study has evaluated the potential cumulative impact of lower income and savings rates on the accumulation of net worth over the lifespan. Participants in the ongoing large, prospective cohort studies will not reach retirement age until 20 to 40 years from now (Altszuler et al., 2016; Barkley et al., 2006; Biederman et al., 2012; Hechtman et al., 2016; Klein et al., 2012; E. B. Owens et al., 2017), precluding a direct test of this question in the near future. In the interim, early financial trajectories can be used to anticipate what will be observed at retirement age and inform the design of data collection during the intervening years. For example, the U.S. Census Bureau has used a synthetic approach to provide intermediate estimates of sex, ethnicity, and occupational differences in earnings over the lifetime without prospectively collecting the 40 years of requisite data (Day & Newburger, 2002; Julian, 2012; Julian & Kominski, 2011).

Third, most prior studies have examined a restricted set of just one or two financial outcomes (e.g., just income) while reporting on outcomes from several different domains. Yet without understanding participants’ pattern of income, savings, credit, rent, debts, and dependence on others, it is difficult to appraise their overall financial status (Gordon & Fabiano, 2019). For example, moderate income might be offset by high debt, or low rates of dependence on public assistance might be offset by high rates of dependence on family.

Fourth, prior studies have relied almost entirely on self-report of financial status. Because individuals with ADHD often exhibit a positive illusory bias (Hoza, Pelham, Dobbs, Owens, & Pillow, 2002; J. S. Owens, Goldfine, Evangelista, Hoza, & Kaiser, 2007; Sibley et al., 2012, 2017) relying on self-report is likely to underestimate the magnitude of the financial deficit associated with ADHD.

Finally, the few extensive prior studies of financial outcomes (Altszuler et al., 2016; Barkley et al., 2008) have not evaluated whether financial impairment is related to the persistence or desistance of ADHD diagnosis/symptoms. Some children with ADHD will no longer exhibit DSM symptoms in adulthood (Sibley et al., 2017) and it is unclear whether financial impairment remains when symptoms have remitted. Recent work (Hechtman et al., 2016; E. B. Owens et al., 2017) has reported relatively small differences in the occupational outcomes of adults whose childhood ADHD has desisted and matched comparisons, so the same may be true of financial outcomes.

The current study addresses the limitations of past literature identified above using data from the Pittsburgh ADHD Longitudinal Study (PALS), a sample of ADHD children and demographically-matched controls that has been followed prospectively for nearly twenty years. Building on our earlier analysis of data from age 25 (Altszuler et al., 2016), in Analysis 1, we compare probands and controls on a broad array of self-reported and parent-reported financial indicators at age 30; evaluate whether probands continue to exhibit financial impairment when ADHD symptoms desist; and test whether proband-control differences in financial outcomes are explained by reduced educational attainment among probands. In Analysis 2, we compare probands’ and controls’ trajectories of financial functioning from age 25 to age 30 to evaluate whether ADHD-related deficits grow, shrink, or remain constant over time. In Analyses 3 and 4, we combine the PALS data with matched Census data to create projections of income over the lifespan and net worth at retirement. Together, these analyses provide the most comprehensive picture to date of the financial prognosis of adults with a history of childhood ADHD.

Methods

Sample

PALS has followed a mixed-age sample of children with ADHD (N=364) and children without ADHD (N=240) for nearly 20 years (Faden et al., 2004; Molina, Sibley, Pedersen, & Pelham, 2016).

Probands.

All attendees of a summer treatment program for ADHD at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center between 1987 and 1996 were re-contacted between 1999 and 2003 and offered enrollment as probands in the PALS study. 364 of a possible 516 enrolled, amounting to 71% of the treatment program attendees during this interval. Those that enrolled exhibited lower average Conduct Disorder symptom ratings (d = 0.30) than those that did not enroll, but these groups were otherwise similar (Molina et al., 2016).

Participation in the summer treatment program required diagnosis of ADHD per DSM-III-R or DSM-IV symptom criteria. Ph.D.-level clinicians conducted a semi-structured interview and reviewed symptom scales completed by teachers and parents in order to confirm the diagnosis of ADHD. Exclusion criteria included a full scale intelligence quotient below 80, a history of seizures, neurological disorders, pervasive developmental disorder, schizophrenia, and/or other psychotic or organic mental disorders (Molina et al., 2016). Other psychiatric comorbidities (e.g., anxiety disorders) were permitted. 47% met DSM symptom criteria for Oppositional Defiant Disorder and 36% met symptom criteria for Conduct Disorder.

All probands received treatment for ADHD during childhood, since they were recruited from attendees of an intensive, 8-week summer treatment program. 90% reported use of stimulant medication at some time in their lifetime, for an average of 5 years medicated between ages 5 and 25. At age 25, 7% of the sample were taking stimulant medication and 8% were taking some other psychoactive medication.

Controls.

A demographically-similar control group was recruited between 1999 and 2001 from a variety of sources, including pediatric practices (41%), advertisements in local newspapers (28%), and local colleges (21%) (Molina et al., 2016). A prospective participant was offered enrollment if his or her age, sex, race, and level of parent education would increase the control group’s rolling similarity to the probands on these characteristics. Table S1 compares baseline characteristics of probands and controls, which are similar except for probands exhibiting lower intelligence quotients (mean = 101) than controls (mean = 111). This difference is expected based on past literature (Frazier, Demaree, & Youngstrom, 2004; Jepsen, Fagerlund, & Mortensen, 2009), and adjusting for intelligence had minimal impact on findings (see supplement).

Overall sample.

In the overall sample, 89% of children were male. 82% of children were white, 10% were black, 5% were mixed race, and 1% were Hispanic. These proportions were broadly representative of the population of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania (84.3% white, 12.4% black, 1.1% mixed race, 0.9% Hispanic) (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000). 29% of children were in single parent households. Median parental income waŝ$64k and at least one parent had graduated college in 55% of families. See prior reports (Faden et al., 2004; Molina et al., 2016) for further information about the PALS sample. This report uses data from two follow-up visits: the target age 25 visit (mean=25.2, SD=0.5) and the target age 30 visit (mean=29.6, SD=0.8). Of relevance to financial outcomes, 18% of these visits occurred within the Great Recession (i.e., December 2007 to June 2009)—this proportion was similar in probands and controls. The institutional review board approved all procedures.

Measures

Finances questionnaire.

Participants and their parents independently completed questionnaires asking about participants’ earnings, savings, dependence on family or others, credit cards, debt, and other relevant financial habits. Items included a mix of binary responses (e.g., “Do you own a home?”), categorical responses (“Mark the interval indicating how much debt you are in.”), and open-ended responses (“How much money do you have in savings?”). The self-report form included 28 items and the parent-report form included 16 items, with some items overlapping across these two forms. Parents did not report on outcomes of which they were unlikely to have knowledge (e.g., balance of participant’s savings account). See supplement for more detail about this questionnaire.

DSM symptoms of ADHD.

Some analyses required identifying which probands no longer met DSM symptom criteria for ADHD as adults (i.e., “desisters”). Both participants and their parents rated DSM-IV symptoms of ADHD at age 30 via the Adult ADHD Scale (Barkley, Fischer, Smallish, & Fletcher, 2002), with a symptom counted as endorsed when rated as occurring “pretty often” or “very often.” Following Hechtman et al. (2016), probands were classified as desisters when neither they nor their parents endorsed 5 or more DSM symptoms of either inattention or impulsivity/hyperactivity. Non-missing parent report was required in order to be classified as a desister. Furthermore, in this report, probands were classified as complete desisters when they exhibited zero DSM symptoms of ADHD per both self- and parent-report. 77% of probands were classified as desisters (N = 227) and 35% of probands were classified as complete desisters (N = 103).

Educational attainment.

Participants reported educational attainment at the age 25 visit on a six-point ordinal scale with the following categories: no high school diploma (1), graduated high school or obtained GED (2), some college (3), Associate’s degree (4), Bachelor’s degree (5), graduate degree (6). Table S2 lists the proportion of probands and controls in each category.

Analyses

Analyses were conducted in the R statistical software environment (v3.6.1) (R Core Team, 2019) unless otherwise specified. Self-report of financial outcomes was present for 474 participants at age 25 and for 435 at age 30. Parent-report of financial outcomes was present for 383 participants at age 25 and for 386 at age 30. Missing data were addressed using multiple imputation by chained equations (White, Royston, & Wood, 2011) (see supplement): N=604 unless otherwise specified.

Analysis 1: Proband/control differences at age 30.

We compared controls and probands at age 30 by regressing each financial outcome on a dummy indicator of ADHD status. Logistic regression was used for binary outcomes and ordinary least squares regression was used for non-binary outcomes. Next, we checked if these results changed when comparing controls to just the probands identified as exhibiting desistant (i.e., <5) or completely desistant (i.e., 0) DSM symptoms of ADHD. Finally, we conducted statistical mediation analysis (MacKinnon, Fairchild, & Fritz, 2007) to test whether educational attainment at age 25 mediated the effect of childhood ADHD (i.e., proband vs. control) on financial outcomes at age 30. Educational attainment was identified as a potential mediator because previous analyses have shown that it predicts financial functioning in this sample (Altszuler et al., 2016). To reduce the number of statistical tests, we fit mediation models for four key financial outcomes at age 30: monthly income, money in savings, living with parents/family, and regularly receiving money from parents/family. The latter two outcomes were combined across informants—if either participant or parent endorsed them, they were counted as positive. For each outcome, a path analysis model was fit in Mplus (v7.4) (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) with educational attainment at age 25 mediating the effect of childhood ADHD (i.e., proband vs. control) on financial outcome at age 30 (Figure S3). The statistical significance of the indirect effect was evaluated using the joint significance test (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002).

Analysis 2: Proband/control differences in change from age 25 to age 30.

We next tested whether the probands and controls differed in financial trajectory from age 25 to age 30. For non-binary outcomes, change scores were computed, then regressed on a dummy indicator of ADHD status and the value of the outcome at age 25 (Kim & Steiner, 2019). For binary outcomes, each participant contributed two rows to the dataset (one for each age of data) and the binary outcome was regressed on dummies indicating ADHD status, timepoint, and the interaction thereof.

Analysis 3: Proband/control differences in projected lifetime income.

Projections of lifetime income and net worth at retirement were restricted to the white, male portion of the sample (N=444). This restriction focused results on the comparison of ADHD and non-ADHD groups (rather, e.g., than effects of child-rearing status on income) and ensured adequate Census coverage for age, education, and employment strata (see supplement). We implemented the synthetic work-life earnings approach of Day and Newburger (2002) using person-level data from the Census’ American Community Survey (ACS) (Ruggles, Genadek, Goeken, Grover, & Sobek, 2017). The income of PALS participants was projected in two ways. In Method A, each member of the sample was assigned the synthetic lifetime income of respondents in the ACS with the same education and employment status as the PALS participant at age 30. This method treats the probands and controls as exchangeable within employment and education strata. In Method B, we relaxed this assumption by estimating how closely the proband and control groups tracked their Census-projected growth in income from age 25 to age 30, then rescaling future growth in income based on this correspondence. See supplement for more detail.

Analysis 4: Proband/control differences in projected net worth at retirement.

Net worth at retirement was also projected in two ways. The first method of projection (Method A) used data from wave 1 of the 2014 Survey on Income and Program Participation (SIPP) panel to calculate the mean net worth at ages 65–69 of Americans at different levels of education. Total net worth was computed in the SIPP using a broad definition of assets, including savings, equities, bonds, businesses, home equity, real estate, and retirement accounts. Each member of the PALS sample was assigned the net worth projection created using respondents in the Census sample with the same education as the PALS participant at age 30. However, this procedure does not account for known ADHD/control differences in employment status (Kuriyan et al., 2013), annual income (Hechtman et al., 2016), or savings behavior (Barkley et al., 2008). The second method of projection (Method B) addressed these limitations by combining the more detailed ACS income data with three assumptions: (a) the savings rate in the control group, (b) the savings rate in the ADHD group, and (c) the annual return on savings (i.e., interest rate). We projected the group difference in net worth at retirement across a range of values for these assumptions.

Results

Analysis 1: Proband/Control Differences at Age 30

Table 1 reports financial outcomes at age 30 for the ADHD and control groups. By self-report, probands were more likely than controls to be unemployed (22% vs. 13%) and living with parents/family (33% vs. 12%), were earning 37% less per month (mean of ~ $2211 vs. $3530), and had 66% less money in savings ($3990 vs. $9970). Probands were also spending less than controls in monthly rent ($490 vs. $852), had fewer credit cards (1.5 vs. 2.7), had been rejected for a credit card more frequently, and were less likely to own a home (22% vs. 42%).

Table 1.

Financial Trajectories of Controls and Probands from Ages 25 to 30

| Inform. | Outcome | Descriptive Statistics | Inference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (or proportion) at age 25 | Mean (or proportion) at age 30 | Change in mean from age 25 to 30 | Diff. at age 30 significant? | Diff.-in-diff. significant? | |||||

| Controls | Probands | Controls | Probands | Controls | Probands | ||||

| Adult | Currently employed full-time | 72% | 50% | 80% | 65% | + 8% | + 15% | * | |

| Currently unemployed | 17% | 28% | 13% | 22% | − 4% | − 6% | * | ||

| Living with parents/family | 28% | 40% | 12% | 33% | − 16% | − 7% | * | *a | |

| Regularly receives money from parents/family | 11% | 12% | 5% | 11% | − 6% | − 1% | * | ||

| Monthly rent/housing expenses | $ 512 [183, 719] | $ 387 [0, 638] | $ 852 [436, 1204] | $ 490 [0, 707] | + 340 | + 103 | * | * | |

| Receiving welfare/government assistance | 2% | 12% | 6% | 11% | + 3% | − 2% | |||

| Monthly income | $ 2556 [974, 3485] | $ 1926 [810, 2832] | $ 3530 [1724, 4548] | $ 2211 [809, 2927] | + 974 | + 285 | * | * | |

| Money in savings account | $ 6247 [0, 4720] | $ 2482 [0, 1400] | $ 9970 [13, 8545] | $ 3990 [0, 2191] | + 3722 | + 1508 | * | * | |

| Number of credit cards | 2.36 [1, 3] | 1.38 [0, 2] | 2.68 [1, 4] | 1.51 [0, 2] | + 0.32 | + 0.13 | * | * | |

| Number of times rejected for credit card | 1.11 [0, 1] | 1.60 [0, 2] | 0.83 [0, 1] | 2.13 [0, 2] | − 0.28 | + 0.53 | * | * | |

| Number of times credit card cancelled by issuer | 0.26 [0, 0] | 0.29 [0, 0] | 0.25 [0, 0] | 0.31 [0, 0] | − 0.01 | + 0.01 | |||

| Ever moved back home after first leaving | 23% | 29% | 28% | 30% | + 6% | + 1% | |||

| How many times moved back home after first leaving | 0.27 [0, 0] | 0.38 [0, 1] | 0.36 [0, 1] | 0.43 [0, 1] | + 0.09 | + 0.04 | |||

| Has debt | 38% | 41% | 41% | 39% | + 3% | − 3% | |||

| Money in debt | $ 1842 [0, 3513] | $ 1889 [0, 3477] | $ 2299 [0, 3400] | $ 2163 [0, 3277] | + 458 | + 274 | |||

| Ever received emergency funds from parents | 31% | 38% | 35% | 37% | + 4% | − 0% | |||

| Number of times in past year received emergency funds from parents | 0.47 [0, 0] | 0.68 [0, 1] | 0.40 [0, 0] | 0.71 [0, 1] | − 0.06 | + 0.03 | |||

| Money in emergency funds received in past year from parents | $ 270 [0, 0] | $ 518 [0, 201] | $ 414 [0, 0] | $ 506 [0, 0] | + 144 | − 13 | |||

| Owns a home | 38% | 33% | 42% | 22% | + 4% | − 11% | * | * | |

| Parent | Living with parents/family | 28% | 35% | 9% | 30% | − 18% | − 5% | * | * |

| Regularly receives money from parents/family | 13% | 20% | 8% | 23% | − 5% | + 2% | * | ||

| Ever received emergency funds from parents | 46% | 55% | 37% | 56% | − 9% | + 1% | * | ||

| Number of times in past year received emergency funds from parents | 1.06 [0, 2] | 1.54 [0, 2] | 0.95 [0, 1] | 2.11 [0, 3] | − 0.10 | + 0.56 | * | * | |

| Money in emergency funds received in past year from parents | $ 427 [0, 348] | $ 590 [0, 376] | $ 1169 [0, 210] | $ 1259 [0, 568] | + 742 | + 668 | |||

| Parent ever co-signed loan | 11% | 8% | 7% | 9% | − 4% | + 0% | |||

| Other adult provides financial assistance | 13% | 20% | 7% | 21% | − 6% | + 1% | * | ||

| Ever moved back home after first leaving | 21% | 33% | 27% | 41% | + 6% | + 8% | * | ||

| How many times moved back home after first leaving | 0.24 [0, 0] | 0.49 [0, 1] | 0.37 [0, 1] | 0.80 [0, 1] | + 0.13 | + 0.31 | * | * | |

Note. Inform. = informant,

= significant per logistic regression but not per linear probability model (see supplement for discussion). Values in “Descriptive Statistics” section are either percentage of sample responding “yes” to criterion, or mean [25th percentile, 75th percentile]. Rightmost two columns indicate statistical significance of (a) the difference between ADHD and control groups at age 30 and (b) of the difference-in-differences from age 25 to 30 (α = .05, all tests two-sided). Coefficients and confidence intervals corresponding to the statistical tests in the rightmost columns are reported in Table S6. N = 604 throughout.

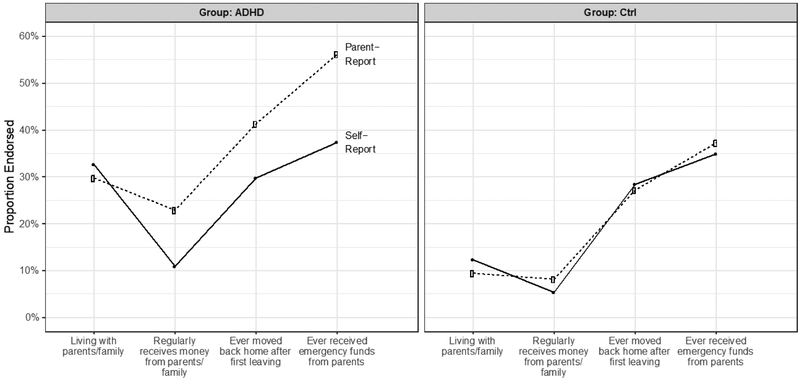

By parent report, probands were more likely than controls to be living with parents/family (30% vs. 9%), to be regularly receiving money from parents (23% vs. 8%), to be receiving financial assistance from a non-parent adult (21% vs. 7%), and to have ever moved back in with parents after first leaving home (41% vs. 27%). Probands were also more likely than controls to have ever received emergency funds from parents and had received them more than twice as often in the past year. Finally, when the same questions were asked of participants and their parents, probands reported lower rates of financial dependence than did their parents (Figure 1). There was no such difference among controls.

Figure 1. Self-Report and Parent-Report Were Discrepant for Probands but not Controls.

Note. Four binary financial status indicators were reported by both participants and their parents. On more subjective indicators (cf. living with parents), adults with a history of childhood ADHD (left panel) provide more positive report than do their parents. No such gap is observed for control adults (right panel).

Controls vs. probands with desistant childhood ADHD.

Follow-up analyses examined whether the proband/control differences observed above remained significant even when the probands’ childhood ADHD had desisted. When comparing controls to only the probands with desistant childhood ADHD (i.e., <5 symptoms), nearly all of the significant probands/control differences (14 of 17) remained statistically significant (Figure S1). When comparing controls to only the probands with completely desistant childhood ADHD (i.e., 0 symptoms), several of the significant proband-control differences (8 of 17) remained statistically significant (e.g., differences on living with parents/family, regularly receiving money from parents/family, receiving financial assistance from a non-parent adult, and having less money in savings account). Thus, even probands who no longer met DSM symptom criteria for ADHD (or exhibited no symptoms whatsoever) showed substantial and pervasive deficits in financial functioning relative to controls. See Table S3 for financial outcomes by symptom status and which specific differences remained statistically significant.

Educational attainment as mediator of proband-control differences in financial outcomes.

Table S4 reports estimated effects from path analysis models with educational attainment mediating the effect of childhood ADHD on financial outcomes. The indirect (i.e., mediated) effect was in the expected direction and statistically significant for all four outcomes: monthly income (p < .001), money in savings (p < .001), living with parents/family (p < .001), and regularly receiving money from parents/family (p < .10). Probands had lower educational attainment at age 25, which in turn was associated with worse financial functioning at age 30. The direct effect was in the expected direction for all four outcomes and statistically significant for three of the four (the exception being money in savings). Thus, there remained a significant direct effect of childhood ADHD on financial outcomes at age 30 that was not mediated by educational attainment at age 25.

Analysis 2: Proband/Control Differences in Change from Age 25 to Age 30

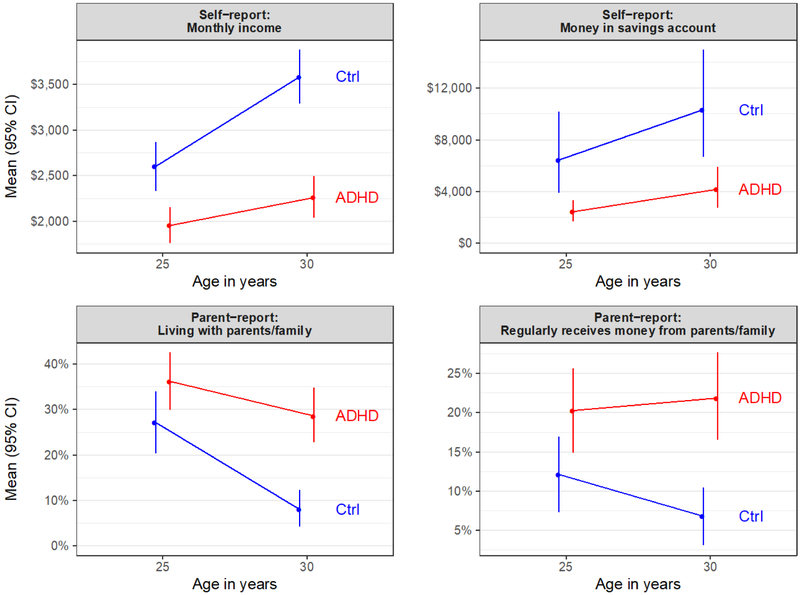

Table 1 reports the change in each group from age 25 to age 30. Figure 2 illustrates four key trends. By self-report, the ADHD group had exhibited a significantly smaller reduction than the control group in the proportion living with parents or family, dropping from 40% to 33% (ADHD) versus from 28% to 12% (control). Probands had increased their monthly income (+$285 vs. +$974), monthly rent (+$103 vs. +$340), and savings (+$1508 vs. +$3722) significantly less than had controls. Probands had acquired fewer additional credit cards than had controls and had been rejected for more new credit card applications. Finally, while the proportion of controls owning a home had increased from 38% to 42%, the proportion of probands owning a home had decreased from 33% to 22%. By parent report, probands had exhibited a significantly smaller reduction than controls in the proportion living with parents/family, and a significantly greater increase than controls in the number of times they moved back in with parents after first moving out. Probands had also increased the number of times they received emergency funds from parents in the past year, while the controls exhibited a slight decrease.

Figure 2. Probands and Controls Diverged between Age 25 and Age 30.

Note. 95% confidence intervals about the means were constructed using nonparametric bootstrap resampling (5000 resamples). Dollar amounts in 2018 USD. Based on available data for each group at each age.

Analysis 3: Proband/Control Differences in Projected Lifetime Income

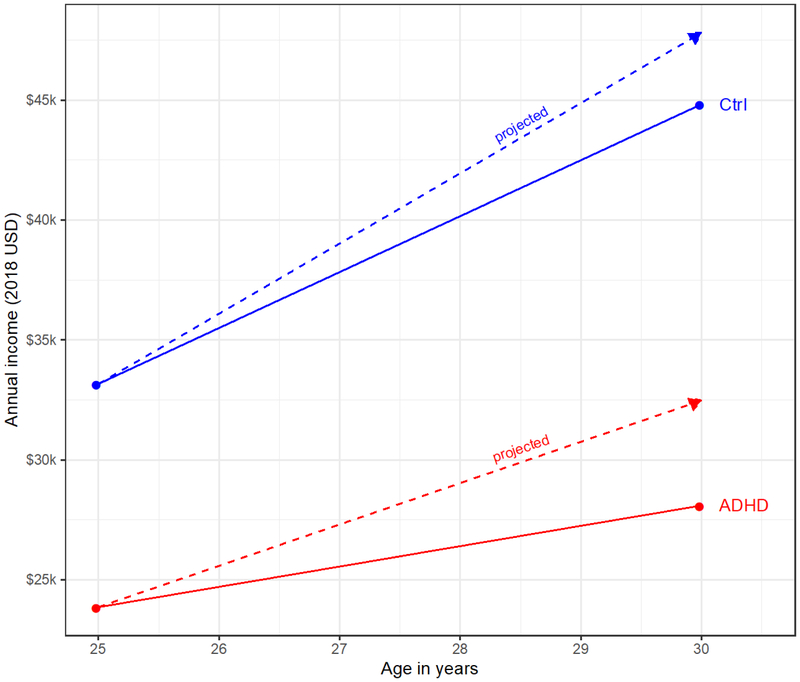

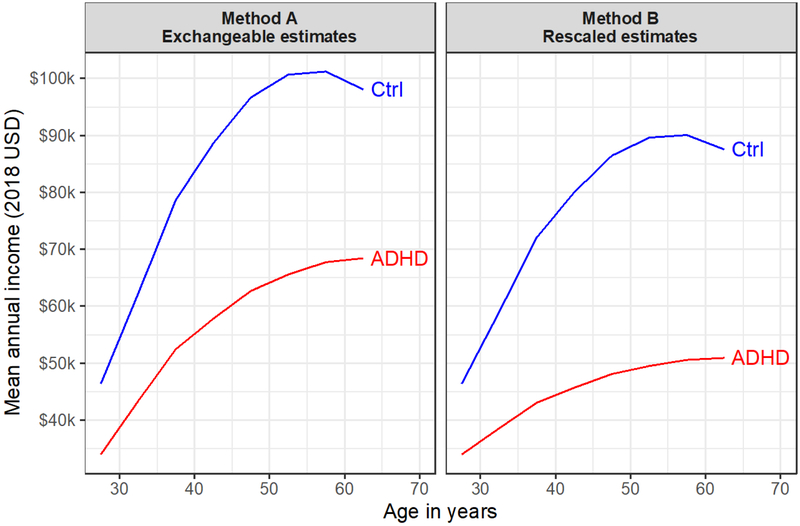

Projections based on education and employment status at age 30 (Method A) suggested that males in the control group would earn $1.10m more than those in the ADHD group over their lifetime ($2.26m vs 3.36m), or 49% more. Examining trajectory from age 25 to age 30, whereas the controls captured most (80%) of the increase in income expected based on their education and employment, the probands captured only half (49%) of the expected increase, displaying flatter income growth than expected (see Figure 3). After rescaling each groups’ projected earnings trajectory accordingly (Method B), the overall deficit associated with ADHD grew to $1.25m. Controls ($3.06m) were expected to earn 70% more than ADHD adults ($1.80m) over their lifetime. Figure 4 shows the projected mean income for the ADHD and control groups across the lifespan.

Figure 3. Male Probands Captured Only Half of Projected Increase in Income from Age 25 to Age 30.

Note. Solid lines indicate actual growth in income observed in PALS data, and dotted lines indicate projected growth in income based on Census data. Male probands increased their income from age 25 to age 30 substantially less than expected, capturing only 49% of anticipated gains in income (i.e., only the shaded part of triangle beneath dotted red line). In contrast, male controls captured most of anticipated gains in income (i.e., the shaded part of triangle beneath dotted blue line). Census projections are based on employment status and education of participants at age 25. Performance relative to Census projections must be interpreted with geographical and secular effects in mind (i.e., participants were seeking work in the Western Pennsylvania economy, and the mean age of participants at start of Great Recession was 25.3; see supplement for further discussion).

Figure 4. Projected Income of Control and Proband Males Across Lifespan.

Note. Based on individuals in Census data matched to ADHD and control groups on employment status and education at age 30. Left panel (Method A) shows estimates treating ADHD and control adults as exchangeable, conditional on education and employment. Right panel (Method B) shows estimates that rescale projections based on the observed degree to which ADHD and control groups tracked their Census projections between ages 25 and 30. Curves in right panel are lower than curves in right panel since both groups underperformed Census projections between ages 25 and 30 (see Figure 3).

Analysis 4: Proband/Control Differences in Projected Net Worth at Retirement

Projections based on the Census’ SIPP data (Method A) suggested that male probands would reach retirement age with a mean net worth 35% lower than that of controls ($410k vs. $630k), reflecting a deficit of $220k. Estimates based on the projected lifetime income (Method B) accounted for group differences in employment patterns and growth in income, but required further assumptions. Group differences in projected net worth at retirement varied greatly as a function of the assumed savings rates and return on investment, ranging from $70k to $1.45m. Assuming savings rates of 5% in both groups and an annual return on investment of 7%, the ADHD group was projected to have 40% lower net worth at retirement (deficit of $270k). When the savings rate was assumed to be lower in the ADHD group (i.e., 3% in ADHD group vs. 5% in control group), the ADHD group was projected to have 64% lower net worth (deficit of $431k). Results under other combinations of assumptions are shown in Table S5 and Figure S2.

Discussion

We used a prospective, longitudinal, case-control design to compare the early trajectories of financial functioning in (a) persons diagnosed with ADHD during childhood and (b) demographically-matched controls with no history of ADHD. At age 30, adults with a history of childhood ADHD showed deficits across almost all financial indicators, including income, savings, employment status, and dependence on parents and other adults. Substantial and pervasive deficits were apparent even when probands no longer met DSM symptom criteria for ADHD (or exhibited no symptoms whatsoever). Moreover, the magnitude of several key ADHD-related deficits had increased from age 25 to age 30. While the control group increased income and savings, moved out from parents’ homes, and transitioned to supporting themselves independently, the ADHD group achieved only small increases in earnings and savings and sustained their financial dependence on parents, family, and other adults. Projections of lifetime income suggest that males with childhood ADHD were expected to earn $1.25m less than controls over the duration of their working life, reaching retirement with 40–75% lower net worth. Taken together, results suggest a poor financial prognosis for the clinic-referred children with ADHD that were followed in this study.

Modal Outcome of Probands at Age 30 was Financial Dependence on Others

The financial status of the ADHD group at age 30 significantly lagged that of the control group at age 25 (Table 1). Even with five additional years of opportunity for occupational development, the adults with a history of childhood ADHD were still reporting lower monthly income, less money in savings, and higher rates of unemployment, living at home, and regularly receiving financial support from others. Combining across informants, two-thirds of the probands exhibited some form of financial dependence at age 30 (cf. 30% of controls). Half were unemployed and/or living with parents (cf. 25%). Nearly half were regularly receiving money from parents, other adults, and/or the government (cf. 20%). Moreover, these statistics may obscure reliance on sources not included in our questionnaire (e.g., spouses, siblings). For example, considering only those in the ADHD group that remained single at age 30, 76% were living with parents and/or regularly receiving money from others.

Probands’ reliance on their parents for housing and income at age 30 may be particularly damaging because parents are nearing retirement age, and thus have fewer resources of their own to share. Continued care is a common burden for parents of children with autism and other developmental disabilities, with findings indicating adverse impact on the physical health, mental health, and finances of parents as these children enter adulthood but remain dependent (Fujiura, 2010; Lunsky, Tint, Robinson, Gordeyko, & Ouellette-Kuntz, 2014; Seltzer, Floyd, Song, Greenberg, & Hong, 2011). Our results suggest that children with ADHD may be on dependence trajectories like those of children routinely viewed as having more serious “childhood” developmental disabilities.

Findings should not be mistaken as indicating that all children with ADHD have poor financial outcomes. While somewhat arbitrary, suppose that we define a “good enough” financial outcome at age 30 as (a) being employed full-time, (b) having more than $400 in savings (i.e., enough to handle an emergency expense; Federal Reserve Board, 2018), and (c) not being reliant on parents, family, other adults, or welfare programs for regular financial support. At age 30, 15% of probands met these criteria for a “good enough” financial outcome (cf. 45% of controls).

Large Financial Deficits Even When DSM Symptoms of ADHD Have Desisted

Unfortunately, even probands who no longer met DSM symptom criteria for ADHD at age 30 still exhibited substantial and pervasive financial deficits relative to controls (Table S3). In other words, remission of DSM symptoms did not imply remission of impairment. Even completely-desistant probands still reported significantly lower income than controls ($2704 vs. $3530), had fewer credit cards (2.7 vs. 5.2), and were more likely to be living with parents (25% vs. 9%) and receiving financial assistance from other adults (19% vs. 7%). While these individuals no longer exhibited any DSM symptoms of ADHD (by self- and parent- report), their poor financial outcomes relative to controls make it difficult to argue they were no longer experiencing the condition (Patterson, 1993). Rather, the DSM symptoms originally written to identify ADHD in childhood (American Psychiatric Association, 1980; Conners, 1969) may fail to capture the nature of ADHD-related deficits in adulthood. Our data show that clinicians should expect residual impairment in a critical area of life functioning (i.e., personal finances) even when adults with a history of ADHD and their parents endorse no current DSM symptoms of ADHD whatsoever (Merrill et al., 2019).

Gap Between Probands and Controls Grows Over Time

Comparison of the age 25 and age 30 data shows that the gap between the ADHD and control groups is growing as the participants become older. Adults with a history of ADHD displayed flatter growth than controls in earnings and savings, and sustained (rather than decreased) financial dependence on parents and others (Figure 2). By age 30, adults with a history of ADHD were already earning 37% less than controls, a reduction similar to that associated with serious mental illness (42%; Kessler et al., 2008) and exceeding those associated with early-onset chronic depression (12–18%; Berndt et al., 2000) or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (16%; Savoca & Rosenheck, 2000). Projections using the matched Census data (Figure 4, Method B) suggest that the ADHD-control gap will widen to an eventual 45% reduction in income at age 50.

We estimated that the probands will reach retirement with mean net worth 40% lower than that of controls, even when accounting only for differences in education accrued by age 30. Yet adults with a history of childhood ADHD save a smaller percentage of their salary (3% vs. 11%; Barkley et al., 2008)) and are less likely to be saving for retirement (29% vs. 55%; Barkley et al., 2008). Estimates accounting for differences in savings and employment patterns suggested the reduction in net worth at retirement is arguably closer to 64%, and quite plausibly as high as 75%. The combination of reduced earning potential and impulsive, present-focused financial decision-making (Barkley et al., 2008) seems likely to produce a high rate of financial difficulties and reliance on others when those with childhood ADHD reach retirement age.

Assuming a prevalence rate of 8.4% (Danielson et al., 2018), our data suggest that the adult sequela of childhood ADHD is associated with $301 billion dollars in annual lost income in the United States (see supplement for back-of-the-envelope calculations). Nonetheless, analyses have likely underestimated the magnitude of the economic deficit associated with childhood ADHD. First, ADHD conveys a substantial positive bias in self-evaluation (Hoza et al., 2002; J. S. Owens et al., 2007; Sibley et al., 2012), and this bias was indeed present in report of financial dependence (Figure 1). Thus, on financial outcomes for which we did not obtain parent report (e.g., income, savings), we likely underestimated the ADHD-related deficit. Second, existing literature suggests that ADHD adults are more likely than controls to quit or lose their jobs, and hold jobs for a shorter duration of time (Barkley et al., 2006; Hechtman et al., 2016; Kuriyan et al., 2013). Since our income projections assumed that employment status was constant beyond age 30, they likely underestimated the ADHD-related deficit.

Clinical Implications

Taken together, results suggest there is great need for interventions that can improve financial functioning as children with ADHD reach young adulthood. However, there has been very little work in this area (Gordon & Fabiano, 2019). Paradigms such as vocational training, supported employment, and counseling on personal finances (Drake, Skinner, Bond, & Goldman, 2009; Marshall et al., 2014; Wehman, Chan, Ditchman, & Kang, 2014) may be of use in developing clinical approaches that can help those with ADHD increase income and savings, improve personal finance habits, and reduce dependence on parents, other adults, and public assistance.

In addition, mediation analyses suggested that lower educational attainment may be a key mechanism driving ADHD-related deficits in long-term financial functioning. Probands were more likely to have dropped out of high school (9% vs. 1%) and less likely to have completed a Bachelor’s degree (14% vs. 53%), two educational milestones that are associated with significant increases in earnings (Day & Newburger, 2002). Thus, educational supports and interventions that can help those with ADHD attain these milestones may be an important means of improving long-term financial outcomes (Evans, Langberg, Egan, & Molitor, 2014; Sibley, Kuriyan, Evans, Waxmonsky, & Smith, 2014). Unfortunately, educational supports for children with ADHD tend to decrease in intensity as they grow older, even as dropout is becoming a more salient possibility (e.g., Wagner, Marder, & Blackorby, 2002).

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first prospective study of the financial outcomes of childhood ADHD to characterize how the deficits associated with ADHD evolve over time. It is also the first study to use early financial trajectories to project net worth at retirement. Our sample size is 2–4 times larger than all prior longitudinal studies except the MTA (Hechtman et al., 2016), our inclusion of parent report is the most extensive to date, and our mean age of follow-up is older than all but one previous study (Klein et al., 2012).

Generalizability of findings may be limited by the sample, which consisted of children with ADHD from treatment-seeking, primarily Caucasian families from a single geographic region. These limitations are endemic to the existing prospective, longitudinal studies with a large cohort of DSM-diagnosed children with ADHD (Barkley et al., 2006; Biederman et al., 2012; Hechtman et al., 2016; Klein et al., 2012; E. B. Owens et al., 2017). Relative to community samples, clinic-referred samples like PALS may (a) exaggerate proband-control differences if families of children with more severe ADHD are more likely to present for treatment or (b) attenuate proband-control differences due to exclusion criteria (e.g., intelligence quotient below 80). While participants were recruited from a single geographic region, the only comparable study that has included children recruited in multiple geographical regions (i.e., the Multimodal Treatment of ADHD Study) has generally failed to find that results vary by site (e.g., Molina et al., 2009). Especially reassuring is that one of these sites was at Pittsburgh, the same location of the PALS sample. Nonetheless, we emphasize that the current results are most justifiably generalized to Caucasian boys with ADHD. Generalizability is also stronger when focusing on the relative financial functioning of probands and controls (e.g., ratio of incomes) since participants’ absolute level of financial functioning may be in part driven by economic conditions in Western Pennsylvania.

In addition, the use of a case-control design limits causal inference. While controls were recruited to match the probands in age, sex, race, and level of parent education, they could not be equated on all features. A portion of the difference in outcome between probands and controls might be caused by differences in factors besides ADHD (Rothman, Greenland, & Lash, 2008), such as psychiatric comorbidities in childhood or adulthood (e.g., SUD, CD). While it is conceptually difficult to separate the effects of related forms of psychopathology (Meehl, 1971; Miller & Chapman, 2001), we emphasize the need for caution in attributing the observed differences solely to ADHD. Similarly, mediation analyses were correlational—the apparent relation between educational attainment and financial outcomes could be driven by other factors (Valente, Pelham III, Smyth, & MacKinnon, 2017).

Additional limitations stem from the measurement of financial outcomes. We did not have access to objective financial records (e.g., tax returns, credit reports, bank statements) that could overcome the positive bias of participants with ADHD’ self-report, produce more accurate income and net worth projections, and reduce our dependence on modeling assumptions. More frequent data collection (e.g., several waves per year) with more granular measures (e.g., expenses separated by spending category, job application behavior among the unemployed, planfulness in money management) would shed light on the specific mechanisms contributing to probands’ poor financial functioning and facilitate the design of supportive interventions (Gordon & Fabiano, 2019).

Conclusion

The financial prognosis of those diagnosed with ADHD during childhood is poor, with the modal outcome at age 30 being dependence on others. Trajectories from age 25 to age 30 indicate sustained or growing deficits relative to controls on nearly all financial measures, suggesting that as participants in the prospective cohort studies grow older, an increasingly negative picture will emerge. Just as children with ADHD may take longer than peers to reach developmental milestones such as staying seated in the classroom, adults with a history of ADHD may take longer than peers to reach financial independence. Interventions for teens and young adults should focus on the development of functional life skills (e.g., with vocational training) rather than just the reduction of DSM symptoms, since substantial deficits were present even for those adults whose symptoms had apparently remitted. The literatures on developmental delay or serious mental illness have long regarded vocational training and support as a primary component of effective treatment of young adults (Burns et al., 2007; Campbell, Bond, & Drake, 2011; Moore & Schelling, 2015; Wehman et al., 2014). Our results suggest that ADHD should likewise be conceptualized as a chronic condition often requiring considerable, potentially lifelong support from others (e.g., family, spouses, social service agencies). Parents may benefit from being informed of this prognosis and its implications for their own financial planning (Zhao et al., 2019).

Supplementary Material

Public Health Significance:

This study underscores the need for clinical interventions that can improve the financial outcomes of children with ADHD in adulthood. Left unaddressed, ADHD-related deficits in financial functioning incur substantial burden to the afflicted, their families, and social welfare programs.

Funding.

This research was funded by grants from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (AA11873) and from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA12414). Additional support was provided by grants from the NIAAA (AA00202, AA08746, AA0626, F31 AA026768), from NIDA (DA05605, DA017546, DA-8-5553, DA034731), from the National Institute on Mental Health (MH097819, MH099030, MH12010, MH4815, MH47390, MH45576, MH50467, MH53554, MH069614), and from the Institute of Education Sciences (IESLO30000665A, IESR324B06045, R324A120169).

Footnotes

Data Transparency Statement:

Data are from the Pittsburgh ADHD Longitudinal Study (PALS), which has been following children prospectively since 1999. Dozens of papers have been published using the PALS data, spanning a broad array of outcome domains and developmental timepoints. The current paper reports on financial outcomes at age 30, the most recently completed follow-up wave, from which no financial data has yet been published. A subset of the age 25 data included as the baseline wave in the current paper were reported in the earlier paper that is referenced in the manuscript.

References

- Abayomi K, Gelman A, & Levy M (2008). Diagnostics for multivariate imputations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics), 57, 273–291. [Google Scholar]

- Ai C, & Norton EC (2003). Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics Letters, 80, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Altszuler AR, Page TF, Gnagy EM, Coxe S, Arrieta A, Molina BSG, & Pelham WE (2016). Financial dependence of young adults with childhood ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 1217–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1980). DSM-III: Diganostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, & Fletcher K (2002). The persistence of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder into young adulthood as a function of reporting source and definition of disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 279–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, & Fletcher K (2006). Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: Adaptive functioning in major life activities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 45, 192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR, & Fischer M (2008). ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt ER, Koran LM, Finkelstein SN, Gelenberg AJ, Kornstein SG, Miller IM, … Keller MB (2000). Lost human capital from early-onset chronic depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 940–947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Woodworth KY, Lomedico A, Hyder LL, & Faraone SV (2012). Adult outcome of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A controlled 16-year follow-up study. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 73, 941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns T, Catty J, Becker T, Drake RE, Fioritti A, Knapp M, … Wiersma D (2007). The effectiveness of supported employment for people with severe mental illness: A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 370, 1146–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Schafer JL, & Kam C-M (2001). A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods, 6, 330–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK (1969). A teacher rating scale for use in drug studies with children. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 126, 884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR (1970). Simple regression In Analysis of Binary Data (pp. 33–42). London: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, & Blumberg SJ (2018). Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47, 199–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JC, & Newburger EC (2002). The big payoff: Educational attainment and synthetic estimates of work-life earnings (No. P23–210). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Skinner JS, Bond GR, & Goldman HH (2009). Social security and mental illness: Reducing disability with supported employment. Health Affairs, 28, 761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans SW, Langberg JM, Egan T, & Molitor SJ (2014). Middle and high school based interventions for adolescents with ADHD. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23, 699–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faden VB, Day NL, Windle M, Windle R, Grube JW, Molina BSG, … Sher KJ (2004). Collecting longitudinal data through childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood: Methodological challenges. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 28, 330–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Reserve Board. (2018). Report on the economic well-being of U.S. households in 2017. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Frazier TW, Demaree HA, & Youngstrom EA (2004). Meta-analysis of intellectual and neuropsychological test performance in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Neuropsychology, 18, 543–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiura GT (2010). Aging families and the demographics of family financial support of adults with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 20, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon CT, & Fabiano GA (2019). The transition of youth with ADHD into the workforce: Review and future directions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 10.1007/s10567-019-00274-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hechtman L, Swanson JM, Sibley MH, Stehli A, Owens EB, Mitchell JT, … Nichols JQ (2016). Functional adult outcomes 16 years after childhood diagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: MTA results. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.07.774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoza B, Pelham WE, Dobbs J, Owens JS, & Pillow DR (2002). Do boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder have positive illusory self-concepts? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 268–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepsen JRM, Fagerlund B, & Mortensen EL (2009). Do attention deficits influence IQ assessment in children and adolescents with ADHD? Journal of Attention Disorders, 12, 551–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian T (2012). Work-life earnings by field of degree and occupation for people with a bachelor’s degree [ACSBR/11–04]. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Julian T, & Kominski R (2011). Education and synthetic work-life earnings estimates (No. ACS-14). U.S. Census Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Heeringa S, Lakoma MD, Petukhova M, Rupp AE, Schoenbaum M, … Zaslavsky AM (2008). Individual and societal effects of mental disorders on earnings in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 703–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, & Steiner PM (2019). Gain scores revisited: A graphical models perspective. Sociological Methods & Research, 0049124119826155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Olazagasti MAR, Roizen E, … & Castellanos FX (2012). Clinical and functional outcome of childhood Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder 33 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69, 1295–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyan AB, Pelham WE Jr., Molina BSG, Waschbusch DA, Gnagy EM, Sibley MH, … Kent KM (2013). Young adult educational and vocational outcomes of children diagnosed with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 27–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunsky Y, Tint A, Robinson S, Gordeyko M, & Ouellette-Kuntz H (2014). System-wide information about family carers of adults with intellectual/developmental disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, & Fritz MS (2007). Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 593–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, & Sheets V (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall T, Goldberg RW, Braude L, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Ghose SS, … Delphin-Rittmon ME (2014). Supported employment: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatric Services, 65, 16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meehl PE (1971). High school yearbooks: A reply to Schwarz. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 77, 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill BM, Molina BSG, Coxe S, Gnagy EM, Altszuler AR, Macphee FL, … Pelham WE (2019). Functional outcomes of young adults with childhood ADHD: A latent profile analysis. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, & Chapman JP (2001). Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, & Pelham WE (2014). Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and risk of Substance Use Disorder: Developmental considerations, potential pathways, and opportunities for research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 607–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, … Houck PR (2009). The MTA at 8 years: Prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 484–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina BSG, Sibley MH, Pedersen SL, & Pelham WE (2016). The Pittsburgh ADHD Longitudinal Study In Hechtman L (Ed.), Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Adult Outcomes and its Predictors. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore EJ, & Schelling A (2015). Postsecondary inclusion for individuals with an intellectual disability and effects on employment. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 19, 130–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén B (2015). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Owens EB, Zalecki C, Gillette P, & Hinshaw SP (2017). Girls with childhood ADHD as adults: Cross-domain outcomes by diagnostic persistence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85, 723–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JS, Goldfine ME, Evangelista NM, Hoza B, & Kaiser NM (2007). A critical review of self-perceptions and the positive illusory bias in children with ADHD. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 10, 335–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR (1993). Orderly change in a stable world: The antisocial trait as a chimera. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 911–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puhani PA (2012). The treatment effect, the cross difference, and the interaction term in nonlinear “difference-in-differences” models. Economics Letters, 115, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundating for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman KJ, Greenland S, & Lash TL (2008). Case-Control Studies. In Modern Epidemiology (3rd ed., pp. 111–127). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB (1976). Inference and missing data. Biometrika, 63, 581–592. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles S, Genadek K, Goeken R, Grover J, & Sobek M (2017). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 7.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Savoca E, & Rosenheck R (2000). The civilian labor market experiences of Vietnam-era veterans: The influence of psychiatric disorders. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 3, 199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Floyd F, Song J, Greenberg J, & Hong J (2011). Midlife and aging parents of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Impacts of lifelong parenting. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 116, 479–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Kuriyan AB, Evans SW, Waxmonsky JG, & Smith BH (2014). Pharmacological and psychosocial treatments for adolescents with ADHD: An updated systematic review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 34, 218–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Waxmonsky JG, … Kuriyan AB (2012). When diagnosing ADHD in young adults emphasize informant reports, DSM items, and impairment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80, 1052–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Swanson JM, Arnold LE, Hechtman LT, Owens EB, Stehli A, … Pelham WE (2017). Defining ADHD symptom persistence in adulthood: Optimizing sensitivity and specificity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 655–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2000). Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000. Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/

- Valente MJ, Pelham III WE, Smyth H, & MacKinnon DP (2017). Confounding in statistical mediation analysis: What it is and how to address it. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64, 659–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Marder C, & Blackorby J (2002). The Children We Serve: The Demographic Characteristics of Elementary and Middle School Students with Disabilities and Their Households. SEELS (Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study) Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED475794 [Google Scholar]

- White IR, Royston P, & Wood AM (2011). Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine, 30, 377–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Page TF, Altszuler AR, Pelham III WE, Kipp H, Gnagy EM, … Pelham WE Jr (2019). Family burden of raising a child with ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47, 1327–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.