Abstract

Background:

Vorapaxar is indicated with standard antiplatelet therapy (APT) in patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) or peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

Objectives:

To evaluate the comparative effects of vorapaxar on platelet-fibrin clot characteristics (PFCC), coagulation, inflammation, and platelet and endothelial function during treatment with daily 81 mg aspirin (A), 75 mg clopidogrel (C), both (C + A), or neither.

Methods:

Thrombelastography, conventional platelet aggregation (PA), ex vivo endothelial function by ENDOPAT, coagulation, platelet activation/inflammation marked by urinary 11-dehydrothromboxane B2 (UTxB2) and safety were determined in patients who were APT naïve (n = 21), on C (n = 8), on A (n = 29), and on A + C (n = 23) during 1 month of vorapaxar therapy and 1 month of offset.

Results:

Vorapaxar had no effect on PFCC, ADP- or collagen-induced PA, thrombin time, fibrinogen, PT, PTT, von Willebrand factor (vWF), D-dimer, or endothelial function (P > .05 in all groups). Inhibition of SFLLRN (PAR-1 activating peptide)-stimulated PA by vorapaxar was accelerated by A + C at 2 hours (P < .05 versus other groups) with nearly complete inhibition by 30 days that persisted through 30 days after discontinuation in all groups (P < .001). SFLLRN-induced PA during offset was lower in APT patients versus APT-naïve patients (P < .05). Inhibition of UTxB2 was observed in APT-naïve patients treated with vorapaxar (P < .05). Minor bleeding was only observed in C-treated patients.

Conclusion:

Vorapaxar had no influence on PFCC measured by thrombelastography, coagulation, or endothelial function irrespective of APT. Inhibition of protease activated receptor (PAR)-1 mediated platelet aggregation by vorapaxar was accelerated by A + C and offset was prolonged by concomitant APT. Vorapaxar-induced anti-inflammatory effects were observed in non-aspirin-treated patients.

Keywords: aspirin, clopidogrel, endothelial function, platelet aggregation, vorapaxar

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, a cyclooxgenase-1 inhibitor and clopidogrel, a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor, is a mainstay pharmacologic strategy to prevent major cardiovascular events from reoccurring in high-risk patients with arterial diseases.1 The pharmacologic limitations and common treatment failure associated with clopidogrel therapy fostered the development and clinical implementation of the more effective P2Y12 receptor blockers, prasugrel and ticagrelor.2 Despite an improved anti-ischemic effect associated with potent P2Y12 inhibitors plus aspirin in high-risk patients with arterial disease, the degree of adverse event reduction (~20% relative and ~2% absolute) compared to clopidogrel therapy in large-scale trials is modest and treatment failure (~10%) persists along with significantly greater bleeding.3 The latter evidence spawned interest in targeting another pathway affecting platelet activation, the protease activated receptor (PAR)-1. In support of this concept, it has been shown that platelet PAR-1 responsiveness is preserved in the presence of adequate P2Y12 receptor inhibition.4

Vorapaxar is a first in class, selective, reversibly binding, orally administered, PAR-1 inhibitor.5 Vorapaxar as monotherapy specifically and strongly inhibited thrombin receptor activating peptide (TRAP)-induced platelet aggregation in healthy volunteers and also when added to aspirin and clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) without significantly increasing bleeding.6,7 In the subanalysis of the Thrombin Receptor Antagonist in Secondary Prevention of Atherothrombotic Ischemic Events (TRA 2P)-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 50 trial, in patients with prior myocardial infarction and no history of stroke or TIA (n = 17 769; 67% of the overall population), vorapaxar therapy when added to standard antiplatelet therapy was associated with a significant reduction in the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular (CV) death, MI, stroke, and urgent coronary revascularization (8.1 versus 9.7%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72–0.89; P < .0001) that was mainly attributed to a significant reduction in MI (5.7 versus 7.0%; HR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.70–0.90; P = .0003). The net clinical outcome favored vorapaxar therapy in this cohort with five fewer fatal events and 45 fewer nonfatal serious events, but 33 additional Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries (GUSTO) moderate bleeding events.8 Based on these results, the United States Food and Drug administration (FDA) approved the use of vorapaxar to reduce the risk of MI, stroke, CV death, and revascularization in patients with a previous MI.9 In addition, vorapaxar was approved for patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD).10

Previous studies have shown significant platelet PAR-1 inhibition by vorapaxar in the presence of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).7 However, the comparative effects of vorapaxar on clot characteristics, coagulation, inflammation, and platelet and endothelial function during treatment with daily 81 mg aspirin, 75 mg clopidogrel, both, or neither, are unknown. We hypothesize that vorapaxar, a potent thrombin receptor antagonist, will reduce thrombin-induced platelet-fibrin clot strength (TIP-FCS) as measured by thromboelastography. Because elevated TIP-FCS has correlated with increased ischemic risk in high-risk coronary artery disease patients, potential modulation in part would provide a mechanism of action to explain the clinical effects of vorapaxar and aid in personalizing therapy in high-risk patients to effectively reduce recurrent thrombotic event occurrence.

2. |. METHODS

This was a phase IV, open label, postmarketing investigation conducted in stable patients between 18–75 years of age. Patients were enrolled if they had ≥2 cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors (hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, obesity, current smoker, diabetes, and ≥55 years of age), prior MI, or PAD. PAD was defined as history of intermittent claudication and resting ankle/brachial index (ABI) of <0.85, or significant peripheral artery stenosis (>50%) documented by angiography or non-invasive testing by duplex ultrasound, previous limb or foot amputation trauma, or aorto-femoral/limb bypass intervention. Exclusion criteria included a history of bleeding diathesis or gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, thrombotic stroke or TIA; illicit drug or alcohol abuse; female subject of child-bearing potential; coagulopathy; planned revascularization or surgery; platelet count < 100 000/mm3; hematocrit < 25%; creatinine > 4 mg/dL; elevated liver enzymes; genetically predicted poor cytochrome (CYP) P450 2C19 metabolizer status; and current use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anticoagulants, or antiplatelet drugs other than aspirin or clopidogrel. The study was performed in accordance with standard ethical principles and approved by the Institutional Review Board at Inova Health System. Written consent was obtained from all patients.

Patients were grouped according to current antiplatelet therapy at the time of enrollment and CVD history. Vorapaxar 2.08 mg was administered daily to all subjects starting on the day of onset and continued for 3–4 weeks. Group 1 included patients with cardiovascular risk factors not on antiplatelet therapy; Group 2 patients had cardiovascular risk factors, were antiplatelet therapy naïve, and received clopidogrel 75 mg daily during a 7–10 day run-in phase prior to vorapaxar dosing; Group 3 included patients on aspirin therapy alone; and Group 4 was composed of patients on aspirin + clopidogrel therapy. A 7–10 day run-in period of 75 mg daily clopidogrel therapy occurred prior to vorapaxar dosing in Group 4 patients if they were not already receiving clopidogrel.

The study comprised six periods: screening, run-in (for Groups 2 and 4), onset and maintenance, offset, and end of study including clinic visits at screening, vorapaxar dosing day, 24 hours post initial vorapaxar dosing, 3–4 weeks postdosing, 2 weeks post-vorapaxar discontinuation, and 4 weeks post-vorapaxar discontinuation (Figure S1 in supporting information). Pharmacodynamic parameters were measured at all time points to assess onset-, maintenance-, and offset-effects of vorapaxar on platelet-fibrin clot generation kinetics and thrombin generation, platelet reactivity, and biomarkers (Figure S1). Reactive hyperemia-peripheral arterial tonometry (RH-PAT) was used to assess endothelial function at pre-dose (Visit 2) and after 3–4 weeks of maintenance therapy (Visit 4). Safety was assessed throughout the study.

2.1 |. Blood and urine sampling

After careful selection of phlebotomy sites, venous blood was collected into Vacutainer® tubes (Becton-Dickinson). After discarding the first 2–3 mL of free-flowing blood, the tubes were filled to capacity and gently inverted 3–5 times to ensure complete mixing of the anticoagulant. Tubes containing 3.2% trisodium citrate were used for light transmission aggregation and for biomarker assays. Lithium heparin (17 USP/mL, Becton-Dickinson) tubes were used for thrombelastography. Blood was collected serially (Figure S1). Urine samples were collected after 1 month of vorapaxar treatment and following 1 month of drug discontinuation for urinalysis to screen for bleeding and 11-dehydrothromboxane B2 (11-dh TxB2).

2.2 |. Thrombelastography (TEG-6S)

The TEG-6S instrument is a microfluidic cartridge-based device capable of performing all current thromboelastographic assays. Unmetered samples are transferred into the cartridge using a disposable dropper or transfer pipette. Once in the disposable, the sample is automatically metered into analysis channels. Reconstitution of reagents dried within the cartridge is accomplished by moving the sample through reagent wells, under the control of microfluidic valves and bellows within the cartridge. After each sample has been mixed with reagent, the system performs a qualitative and quantitative assessment of hemostasis. A Citrated Multi-Channel cartridge (CM) was used to measure hemostasis including thrombin generation kinetics. The standard CM assay provides measures of clotting time (R, a measure of the enzymatic phase of coagulation), clot kinetics (K), thrombin induced platelet-fibrin clot strength (MA or TIP-FCS), fibrinolysis (LY), and functional fibrinogen levels (FF).11

2.3 |. Platelet aggregation

Blood-citrate tubes were centrifuged at 120 g for approximately 5 minutes to recover platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and was further centrifuged at 850 g for approximately 10 minutes to recover platelet-poor plasma. Platelet aggregation was completed within 2 hours of blood collection and was assessed using a Chronolog Lumi-Aggregometer (model 490–4D) with the AggroLink software package as previously described.12 Maximal and final aggregation values (aggregation at 6 minutes) were recorded following stimulation of PRP with 5 μmol/L adenosine diphosphate (ADP), 15 μmol/L SFLLRN (PAR-1 activating peptide), and 4 μg/mL collagen with platelet-poor plasma used as a reference. Maximal aggregation was determined at the time of maximal change in light transmittance and final aggregation was determined at 6 minutes poststimulation.

2.4 |. Coagulation markers

D-dimer, fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor (vWF) activity and antigen, thrombin time (TT), prothrombin time (PT), and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) were performed on ACL TOP 300 Haemostasis system (Instrumentation Laboratory) according to the standard analytical methods.13

2.5 |. Urinary 11-dehydro-thromboxane B2

Urine samples were stored at −70°C and shipped on dry ice to the Inflammatory Markers Laboratory for analysis. Urinary 11-dh TxB2 (UTxB2), a marker of aspirin response and inflammation, were measured using the AspirinWorks™ ELISA assay (Corgenix).14 Briefly, 100 μL of urine in assay buffer was incubated with mouse monoclonal antibody and 11-dh TxB2-alkaline phosphatase tracer in a competitive fashion. UTxB2 concentrations were determined by measuring color development at 405 nm with an Absorbance Microplate reader and expressed as pg/mL. Final results are reported as pg UTxB2 per mg creatinine to normalize results for urine concentration.

2.6 |. CYP2C19 genotyping

Polymorphisms of CYP2C19 *2, *3, *17 were determined by the Spartan RX CYP2C19 assay. After rinsing the patient’s mouth with water, we performed buccal swabs and samples in each of the three swabs were inserted into wells and processed by Spartan RX Analyzer.15 The time from sample acquisition to result was about 60 minutes. Genotype was grouped as ultrarapid metabolizer (UM, including *17/*17, *1/*17), extensive metabolizer (EM, including *1/*1), intermediate metabolizer (IM, including *1/*2, *1/*3, *2/*17, *3/*17), and poor metabolizer (PM, including *2/*2, *3/*3, *2/*3).

2.7 |. Reactive hyperemia-peripheral arterial tonometry (RH-PAT)

Endothelial function was assessed using the ENDOPAT System (Itamar Medical, Caesarea, Israel), a pulsatile arterial tonometry-based diagnostic device, as previously described.12 The reactive hyperemia index, a measure of endothelial function, and the augmentation index, a measure of arterial stiffness, were determined. Endothelial dysfunction is defined as reactive hyperemia index < 1.67. Normal arterial stiffness is defined as an augmentation index −30% to −10%, increased arterial stiffness as an augmentation index more than −10% to 10%, and abnormal arterial stiffness as an augmentation index > 10%.

2.8 |. Safety assessments

Safety assessments for this trial included adverse events (AEs) including bleeding after the first administration of study treatment through the end of participation in the study. These safety assessments evaluated the nature, intensity, and duration of all treatment-related adverse events and their relationship to the study treatments. In addition, the safety of all subjects was assessed by clinical laboratory measurements, physical examinations, and vital signs.

2.9 |. Endpoints

2.9.1 |. Primary

The primary endpoint was the change in platelet-fibrin clot formation by thrombelastography (R, TIP-FCS, α, and LY30) compared to predose within and between each treatment group.

2.9.2 |. Secondary

The secondary endpoints of this study were (a) percent change in 5 μmol/L ADP-, 15 μmol/L SFLLRN (TRAP)-and 4 μg/mL collagen-induced maximal and final aggregation by light transmittance aggregation during onset, maintenance, and offset of vorapaxar treatment compared to predose within and between each treatment group; (b) change in biomarkers (PT, PTT, D-dimer, thrombin time, fibrinogen, vWF (activity and antigen), during onset, maintenance, and offset of vorapaxar treatment compared to predose within and between each treatment group; (c) changes in urinary 11-dehydro (dh)-thromboxane A2 during maintenance and offset of vorapaxar treatment compared to predose within and between each treatment group; (d) change in reactive hyperemia index (RHI) as assessed using the ENDOPAT system between predose and maintenance therapy within and between the treatment groups.

2.10 |. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented for continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages are presented for categorical variables. The chi-squared test was used to determine whether there is a significant difference in frequencies between treatment groups. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine normality of data. A repeated measure of variance and paired t-test analyses were used for within and between group comparisons for normally distributed data, while the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparisons as a nonparametric. A P-value < .05 was considered a significant difference between treatments. All analyses were performed using SAS® for Windows, version 9.3 or later.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Study population

Baseline demographics and laboratory data are shown in Tables 1 and 2. A total of 81 of 84 consented patients met screening criteria, received study treatment, and were included in the analysis. A total of 7% of the enrolled subjects (6/81) discontinued due to adverse events after study treatment including minor bleeding in the clopidogrel groups (Table S1 in supporting information). The mean age of the study population was 63.0 ± 8.0 years and mean body mass index of 30.4 ± 6.2 kg/m2. The majority of patients were men, on statin therapy, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors. Hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia were common risk factors. Patients on antiplatelet therapy more frequently had prior revascularization, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, hyperlipidemia, and use of concomitant medications (statin therapy, beta blockers, and ACE inhibitors).

TABLE 1.

Patient demographics

| Characteristics | Total group (n = 81) |

APT (n = 21) |

Clopidogrel (n = 8) |

Aspirin (n = 29) |

Clopidogrel + as- pirin (n = 23) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.0 ± 8.0 | 60.4 ± 9.8 | 64.2 ± 7.2 | 63.6 ± 7.7 | 64.2 ± 6.7 | .15 |

| Male (n, %) | 58 (72) | 14 (67) | 8 (100) | 19 (66) | 17 (74) | .42 |

| Caucasian (n, %) | 62 (77) | 17 (81) | 6 (75) | 22 (76) | 17 (74) | .44 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.4 ± 6.2 | 32.4 ± 6.7 | 26.6 ± 3.5 | 30.3 ± 6.0 | 30.0 ± 6.2 | .15 |

| Systolic BP (mm/Hg) | 134 ± 20 | 135 ± 17 | 121 ± 18 | 137 ± 19 | 135 ± 24 | .27 |

| Diastolic BP (mm/Hg) | 76 ± 12 | 77 ± 13 | 74 ± 13 | 76 ± 10 | 76 ± 14 | .91 |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Prior PCI/CABG | 33 (41) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (38) | 12 (41) | 18 (78) | <.001 |

| Prior stroke | 3 (4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 2 (9) | .42 |

| Myocardial infarction | 27 (33) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 12(41) | 15 (65) | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 7 (9) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) | 3 (10) | 2 (9) | .78 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 13 (16) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (24) | 6 (26) | .005 |

| Current smokers | 32 (40) | 8 (38) | 4 (50) | 11 (38) | 9 (39) | .56 |

| Hypertension | 57 (70) | 17 (81) | 4 (50) | 19 (66) | 17 (74) | .32 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 65 (80) | 14 (67) | 6 (75) | 24 (83) | 21 (91) | .004 |

| Diabetes | 22 (27) | 3 (14) | 3 (38) | 5 (17) | 11 (48) | .06 |

| GERD | 16 (20) | 4 (19) | 0 (0) | 8 (28) | 4 (17) | .17 |

| Medications | ||||||

| Statins | 66 (82) | 11 (52) | 8 (100) | 26 (90) | 21 (91) | .002 |

| Beta blockers | 39 (48) | 5 (24) | 5 (63) | 13 (45) | 16 (70) | .02 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 10 (12) | 5 (24) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7) | 3 (13) | .21 |

| Proton pump inhibitors | 14 (17) | 4 (19) | 1 (13) | 7 (24) | 2 (9) | .51 |

| ACE inhibitors | 25 (31) | 1 (5) | 4 (50) | 10 (35) | 10 (44) | .02 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; APT, antiplatelet therapy; BP, blood pressure; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

TABLE 2.

Baseline laboratory and endothelial function measurements

| Total group (n = 81) |

APT (n = 21) |

Clopidogrel (n = 8) |

Aspirin (n = 29) |

Clopidogrel + aspirin (n = 23) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine (ng/mL) | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | .15 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (g/dL) | 18 ± 7 | 17 ± 6 | 16 ± 7 | 20 ± 8 | 17 ± 6 | .42 |

| Alkaline phosphate | 78 ± 26 | 86 ± 25 | 78 ± 29 | 82 ± 21 | 66 ± 27 | .23 |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 28 ± 15 | 29 ± 18 | 26 ± 10 | 26 ± 13 | 29 ± 16 | .87 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 27 ± 17 | 27 ± 18 | 22 ± 6 | 25 ± 9 | 30 ± 25 | .60 |

| Platelets (×1000/mm3) | 228 ± 59 | 248 ± 56 | 212 ± 36 | 236 ± 62 | 206 ± 59 | .08 |

| C-reactive protein | 0.9 ± 2.4 | 0.5 ± 0.6 | 2.4 ± 4.1 | 0.6 ± 1.4 | 1.0 ± 3.4 | .27 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 42 ± 6 | 42 ± 4 | 43 ± 4 | 42 ± 4 | 42 ± 9 | .97 |

| Endothelial function (n, %) | ||||||

| Arterial stiffness (AI > 10%) | 44 (54) | 6 (29) | 5 (63) | 18 (62) | 15 (65) | .12 |

| Arterial dysfunction (RHI < 1.67) | 28 (35) | 5 (24) | 3 (38) | 11 (40) | 9 (39) | .87 |

| CYP2C19 metabolizer status (n, %) | ||||||

| Ultra-rapid | 9 (29) | - | 3 (38) | - | 6 (26) | .52 |

| Extensive | 16 (52) | - | 3 (38) | - | 13 (57) | .36 |

| Intermediate | 6 (19) | - | 2 (25) | - | 4 (17) | .63 |

Abbreviations: AI, augmentation index; APT, antiplatelet; CYP, cytochrome; RHI, reactive hyperemia index.

3.2 |. Primaryoutcomes

The mean data from all visits and groups are presented in Table 3. There was no effect of vorapaxar on clotting time, clot kinetics, clot strength, functional fibrinogen levels, or clot lysis observed between time points and between treatments groups (P > .05 by repeated measures ANOVA).

TABLE 3.

Thrombelastography results

| Onset and maintenance |

30 d offset |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screen | Predose | 2 h | 24 h | 30 d | 45 d | 60 d | |

| CK-R, (ref range 4.6–9.1 min) | |||||||

| APT naive | 6.5 ± 0.7 | 6.7 ± 1.4 | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 6.3 ± 1.4 | 6.6 ± 1.0 | 6.5 ± 1.2 |

| C only | 5.8 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 5.6 ± 1.2 | 6.6 ± 0.8 | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 6.1 ± 0.8 |

| ASA only | 6.6 ± 1.0 | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 6.1 ± 1.1 | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 6.6 ± 1.0 |

| C + ASA | 6.0 ± 1.2 | 6.0 ± 1.6 | 5.6 ± 1.5 | 6.5 ± 0.8 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 6.4 ± 0.8 | 6.4 ± 1.2 |

| CK-K, (ref range 0.8–2.1 min) | |||||||

| APT naive | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.4 |

| C only | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| ASA only | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 |

| C + ASA | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| CK-MA or TIP-FCS, (ref range 52–69 mm) | |||||||

| APT naive | 61.1 ± 3.8 | 61.2 ± 3.2 | 61.0 ± 3.7 | 60.9 ± 4.1 | 62.8 ± 3.7 | 61.8 ± 4.6 | 61.2 ± 4.1 |

| C only | 60.1 ± 7.3 | 61.4 ± 4.7 | 60.9 ± 3.8 | 61.6 ± 2.4 | 61.2 ± 4.1 | 61.0 ± 5.3 | 59.9 ± 4.8 |

| ASA only | 62.0 ± 3.4 | 61.7 ± 5.0 | 62.7 ± 3.6 | 62.0 ± 4.4 | 61.6 ± 4.3 | 62.2 ± 3.1 | 62.2 ± 3.5 |

| C + ASA | 61.7 ± 4.4 | 61.9 ± 4.4 | 61.1 ± 6.9 | 60.2 ± 10.5 | 62.2 ± 3.7 | 62.2 ± 3.3 | 62.3 ± 2.8 |

| Functional fibrinogen, (ref range 15–32 mm) | |||||||

| APT naive | 21.3 ± 3.6 | 21.9 ± 4.0 | 22.0 ± 3.8 | 21.8 ± 3.7 | 21.9 ± 3.5 | 22.2 ± 4.7 | 21.2 ± 3.8 |

| C only | 20.8 ± 4.9 | 20.4 ± 4.9 | 19.7 ± 2.6 | 19.9 ± 2.3 | 19.1 ± 2.8 | 19.2 ± 4.4 | 18.3 ± 2.9 |

| ASA only | 24.1 ± 6.5 | 22.6 ± 5.9 | 22.1 ± 5.2 | 22.1 ± 5.8 | 21.6 ± 4.0 | 21.9 ± 7.0 | 22.4 ± 5.6 |

| C + ASA | 21.5 ± 4.8 | 21.6 ± 5.1 | 20.1 ± 7.7 | 22.5 ± 7.4 | 22.1 ± 6.7 | 21.9 ± 5.8 | 21.4 ± 5.0 |

| LY30 (ref range 0%−2.6%) | |||||||

| APT naive | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.8 ± 0.8 | 0.9 ± 0.8 | 0.5 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.7 |

| C only | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.7 | 0.4 ± 0.5 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.5 |

| ASA only | 0.4 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.6 ± 0.3 |

| C + ASA | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 1.1 | 0.3 ± 0.4 |

Abbreviations: APT, antiplatelet therapy; ASA, aspirin; C, clopidogrel.

3.3 |. Secondary outcomes

3.3.1 |. Platelet aggregation

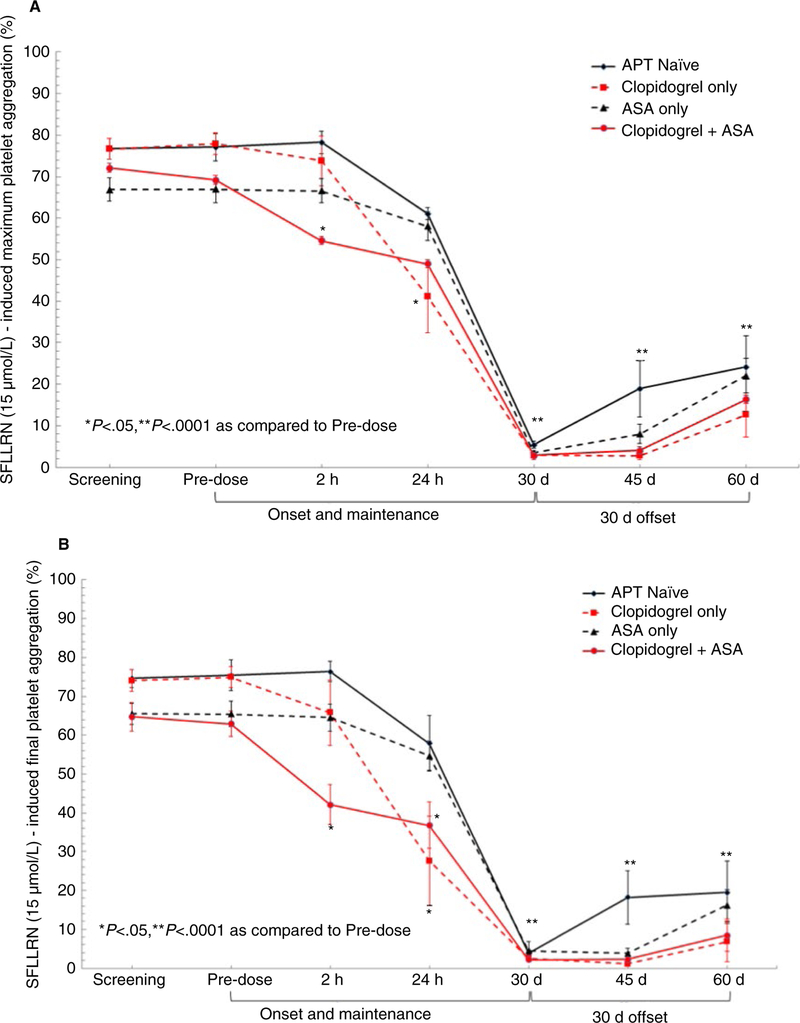

Maximal and final SFLLRN-induced aggregation were similar between groups at pre-dose (Figure 1A,B). At 2 hours after vorapaxar administration, maximal and final SFLLRN-stimulated platelet aggregation were lower in patients treated with clopidogrel + aspirin (P < .05 versus other groups). At 24 hours post-vorapaxar, patients treated with clopidogrel had lower SFLLRN-stimulated platelet aggregation (P < .05 versus APT naïve and aspirin [ASA]-only group). Nearly complete inhibition of maximal and final SFLLRN-stimulated platelet aggregation was observed at 30 days in all groups. Persistent, significant inhibition of SFLLRN-induced platelet aggregation was still observed at 30 days after discontinuation with the slowest recovery occurring in patients treated with clopidogrel compared to APT-naïve patients (P < .05) (Figure 1A,B).

FIGURE 1.

A,B, SFLLRN (15 μmol/L)-induced maximum and final platelet aggregation

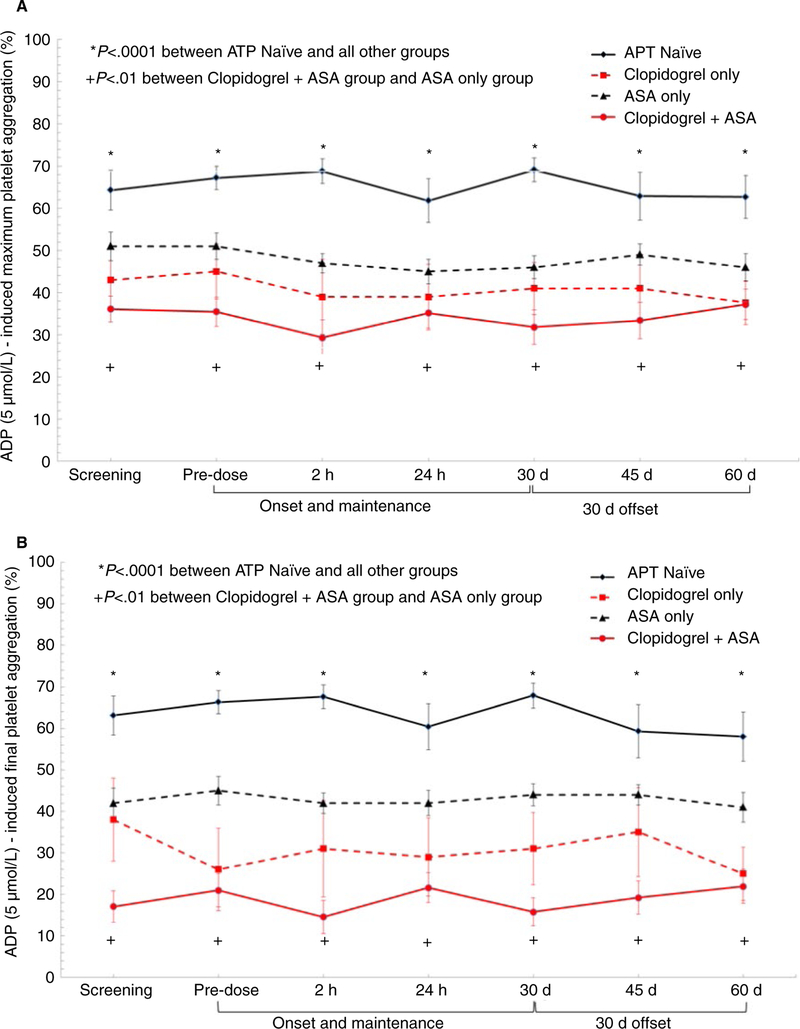

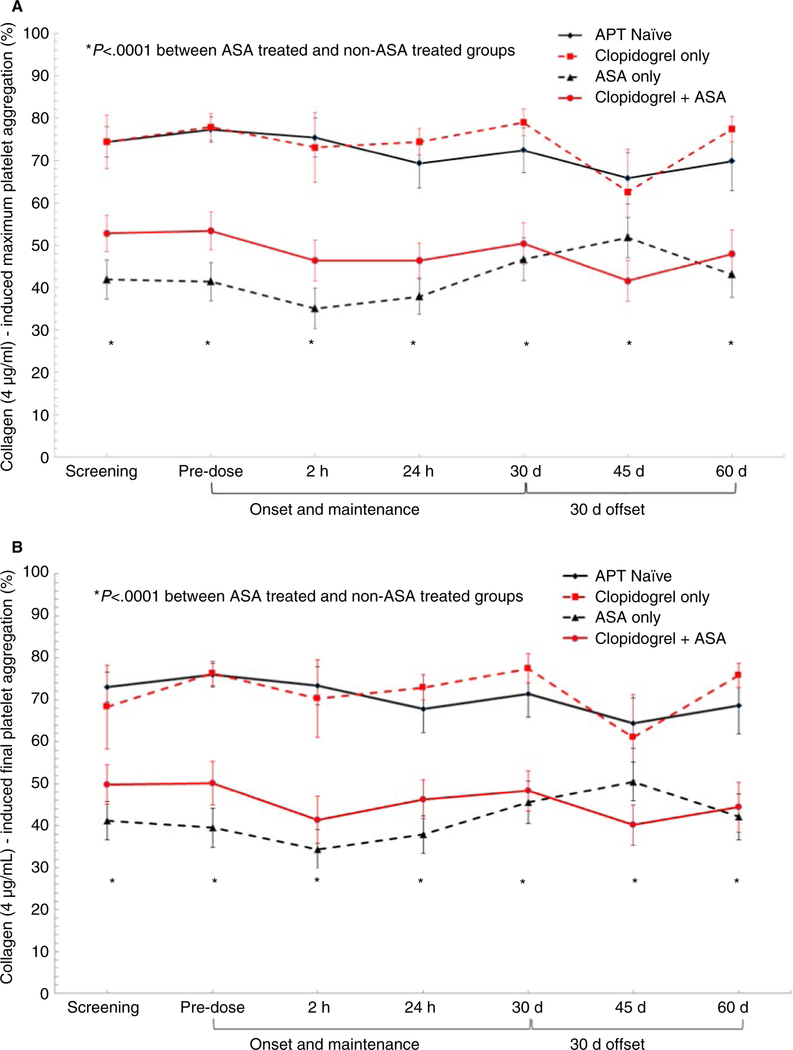

Adenosine diphosphate-induced aggregation was unaffected by the addition of vorapaxar to APT-naïve and all APT groups. As expected, patients on APT had significantly lower platelet aggregation than the APT-naïve group (P < .0001) with clopidogrel + aspirin group demonstrating the lowest ADP-induced platelet aggregation (Figure 2A,B). Inhibition of collagen-induced aggregation was unaffected by the addition of vorapaxar to APT naïve and all APT groups. As expected, patients on ASA therapy had significantly lower collagen-induced platelet aggregation than non-ASA treated groups (P < .0001) (Figure 3A,B).

FIGURE 2.

A,B, Adenosine diphosphate (5 μmol/L)-induced maximum and final platelet aggregation

FIGURE 3.

A,B, Collagen (4 μg/mL)-induced maximum and final platelet aggregation

3.3.2 |. Coagulation/endothelial markers

There was no significant change in thrombin time, D-dimer, fibrinogen, vWF (activity and antigen), TT, PT and PTT between time points or treatment groups (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Plasma platelet/endothelial markers

| ATP Naïve (n = 21) Mean ± SD |

Clopidogrel Only (n = 8) Mean ± SD |

Aspirin only (n = 29) Mean ± SD |

Clopidogrel + aspirin(n = 23) Mean ± SD |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombin time, (ref range 10.3–16.6 s) | ||||

| Predose | 12.6 ± 1.2 | 12.7 ± 0.4 | 12.4 ± 1.1 | 12.4 ± 1.1 |

| 30 d (last day MD) | 12.5 ± 1.4 | 12.8 ± 1.1 | 12.6 ± 1.4 | 12.5 ± 1.2 |

| 60 d (last day offset) | 12.2 ± 1.0 | 12.0 ± 1.0 | 13.0 ± 1.3 | 12.5 ± 1.1 |

| D-dimer (ref range < 500 ng/mL) | ||||

| Predose | 161 ± 99 | 170 ± 118 | 193 ± 106 | 218 ± 133 |

| 30 d (last day MD) | 144 ± 73 | 161 ± 115 | 215 ± 100 | 182 ± 97 |

| 60 d (last day offset) | 157 ± 97 | 162 ± 94 | 164 ± 74 | 226 ± 144 |

| Fibrinogen (ref range 189–458 mg/dL) | ||||

| Predose | 428 ± 81 | 459 ± 74 | 416 ± 88 | 400 ±123 |

| 30 d (last day MD) | 422 ± 36 | 487 ± 78 | 393 ± 99 | 376 ± 88 |

| 60 d (last day offset) | 424 ± 71 | 361 ± 61 | 399 ± 98 | 386 ± 75 |

| vWF activity (ref range 50%−217%) | ||||

| Predose | 132 ± 28 | 116 ± 40 | 124 ± 29 | 135 ± 48 |

| 30 d (last day MD) | 130 ± 36 | 137 ± 40 | 132 ± 48 | 137 ± 45 |

| 60 d (last day offset) | 128 ± 22 | 128 ± 33 | 136 ± 30 | 143 ± 28 |

| vWF antigen (ref range 50%–249%) | ||||

| Predose | 161 ± 47 | 148 ± 57 | 144 ± 25 | 179 ± 44 |

| 30 d (last day MD) | 160 ± 38 | 150 ± 57 | 158 ± 59 | 162 ± 60 |

| 60 d (last day offset) | 156 ± 42 | 152 ± 54 | 162 ± 48 | 173 ± 56 |

| Prothrombin time (ref range 9–11.5 s) | ||||

| Predose | 10.9 ± 0.9 | 10.6 ± 0.4 | 10.8 ± 48 | 10.7 ± 0.8 |

| 30 day (last day MD) | 10.5 ± 0.6 | 10.4 ± 0.5 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 10.6 ± 0.8 |

| 60 d (last day offset) | 10.2 ± 0.6 | 9.9 ± 0.2 | 10.4 ± 0.4 | 10.5 ± 0.8 |

| Partial thromboplastin time (ref range 22–34 s) | ||||

| Predose | 30.0 ± 6.5 | 26.4 ± 2.7 | 29.9 ± 4.7 | 27.8 ± 2.0 |

| 30 d (last day MD) | 27.2 ± 3.0 | 26.7 ± 2.3 | 28.4 ± 2.1 | 27.1 ± 2.6 |

| 60 d (last day offset) | 27.3 ± 2.9 | 25.7 ± 2.2 | 28.1 ± 3.0 | 26.5 ± 2.9 |

Abbreviation: MD, maintenance dose; vWF, Von Willebrand factor.

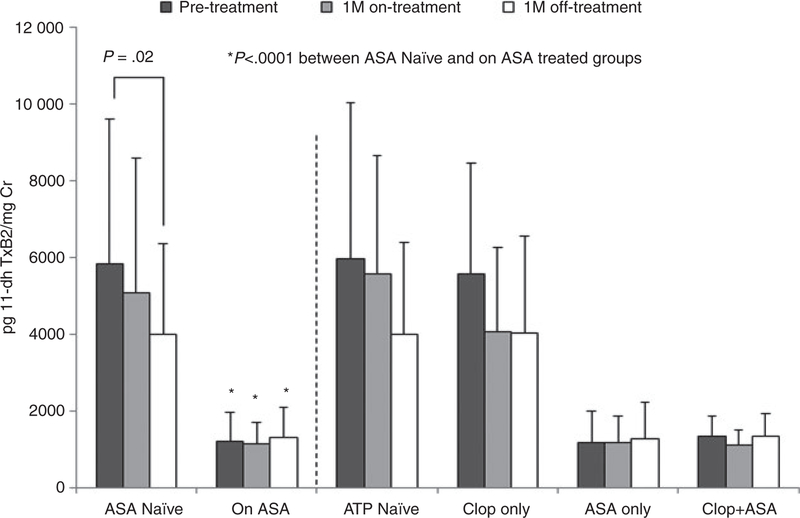

3.3.3 |. Urinary 11-dehydro (dh)-thromboxane A2

Changes in urinary 11-dehydro thromboxane B2 were evaluated after 1 month of vorapaxar treatment and following 1 month of drug discontinuation (Figure 4). Patients within the ASA group had significantly lower mean 11-dehydro thromboxane B2 levels compared to non-ASA-treated patients. A stepwise reduction in urinary 11-dehydro thromboxane B2 levels was observed.

FIGURE 4.

Urinary 11-dehydro thromboxane B2 metabolite

3.4 |. Reactive hyperemia-peripheral arterial tonometry (RH-PAT)

Changes in endothelial function as measured by reactive hyperemia-peripheral arterial tonometry were evaluated after 1 month of vorapaxar treatment. Augmentation index, a measure of arterial stiffness, and reactive hyperemia index, a measure of arterial function and PAD, were determined. Arterial stiffness (AI > 10%) was identified in 54.3% of the total study population with the highest proportion observed in patients on APT therapy compared to APT-naïve group. Arterial dysfunction (RHI < 1.67) was observed in 34.5% of the total study population, with the highest proportion observed in patients on APT therapy compared to APT naïve group (Table 2, Figure S2 in supporting information). The addition of vorapaxar had no effect on frequency of arterial dysfunction or mean AI and RHI.

3.5 |. Safety assessments

There was one serious adverse event in the ASA-only group not related to treatment and one treatment-related SAE in clopidogrel + ASA group related to bleeding. From the safety population, 12 subjects (14.8%, 12/81) reported one or more AEs in this study (Table S1). The majority of reported AEs were minor bleeding and occurred more frequently in clopidogrel-treated groups as compared to non-clopidogrel-treated groups (29.0% versus 0%, P < .0001). Furthermore, patients experiencing a minor bleeding event had significantly lower ADP-induced PA (Figure S3) but no major difference in collagen or TRAP-induced aggregation as compared to no bleeding group. A total of six patients discontinued early due to adverse event occurrence.

4 |. DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the comparative pharmacodynamic effects of vorapaxar in an antiplatelet-naïve population and in patients treated with various standard antiplatelet regimens. We also analyzed the effects of vorapaxar on thrombelastographic indices; effects heretofore unknown. The major findings of our study were: (a) there was no demonstrable effect of vorapaxar on clot viscoelastic parameters measured by thrombelastography; (b) vorapaxar had no effect on ADP- or collagen-induced platelet aggregation, coagulation, or endothelial function determined by ENDOPAT; (c) inhibition of PAR-1 mediated platelet aggregation by vorapaxar was accelerated by dual antiplatelet therapy and offset was prolonged by concomitant antiplatelet therapy; (d) potent PAR-1 inhibitory effects of vorapaxar remain at 30 days after discontinuation irrespective of concomitant antiplatelet therapy; (e) an anti-inflammatory/antiplatelet activation effect was observed in patients not on aspirin; and (f) bleeding was only observed in patients treated with clopidogrel.

Recurrent atherothrombotic events in patients with coronary, cerebrovascular, and peripheral arterial disease remain unacceptably high despite advances in revascularization and antithrombotic therapy. 3 Data suggest that selected patients following percutaneous coronary intervention with shigh viscoelastic clot strength indicative of a robust response to thrombin are at higher risk for thrombotic events.16 Vorapaxar selectively inhibits the cellular actions of thrombin through antagonism of the PAR-1 receptor. By inhibiting thrombin-induced platelet aggregation, vorapaxar confers clinical antithrombotic effects.7

Mechanistic studies of vorapaxar thus far have largely focused on the measurement of platelet aggregation.5 However, blockade of PAR-1 on extra-platelet sites (eg, endothelium, leukocytes) by vorapaxar may confer effects that modulate atherogenesis.17 Moreover, pharmacodynamic studies have ignored potential effects of vorapaxar on the viscoelastic and kinetic characteristics of platelet-fibrin clot formation, potential factors that may play a role in the development of adverse thrombotic events.18 In the Clopidogrel with Eptifibatide to Arrest the Reactivity of Platelets study (CLEAR Platelets II study), Gurbel et al19 demonstrated a significant reduction in thrombin-induced platelet-fibrin clot strength with GPIIb/IIIa blockade with eptifibatide and a non-significant reduction using a direct thrombin inhibitor bivalirudin in patients undergoing elective coronary stenting. We assumed that sustained blockade of PAR-1 with vorapaxar would also provide a reduction in platelet-fibrin clot formation. Finally, these studies have not delineated potential differential effects of vorapaxar when added to antiplatelet-naïve patients and patients on monoor dual-antiplatelet therapy. Therefore, in addition to effects on platelet aggregation, we studied the effects of vorapaxar on clot kinetics and viscoelasticity, endothelial function, thrombin generation, and inflammation when given to antiplateletnaïve patients and patients treated with mono-and dual-antiplatelet therapy with daily 81 mg aspirin and 75 mg clopidogrel.

Using thrombelastography, we showed that vorapaxar did not cause a significant change in clot viscoelasticity, and there were no demonstrable effects on endothelial function, fibrin generation, and platelet aggregation via ADP- and collagen-induced pathways. Furthermore, our findings are concordant with previous observations; vorapaxar alone and or when added to concomitant antiplatelet therapy did not have an effect on markers of coagulation including D-dimer, TT, PT, PTT, fibrinogen, and vWF.6,20 Other investigators have reported no effects on ADP- and collagen-induced aggregation.6 However, vorapaxar administration did lead to a marked inhibition of SFLLRN-stimulated platelet aggregation in all groups, which remained potent at 30 days after discontinuation. These findings suggest that vorapaxar has a high level of specificity in its mechanism of action on platelet aggregation through PAR-1 inhibition. Interestingly, the sustained inhibition at 30 days was more pronounced when vorapaxar was co-administered with the P2Y12 inhibitor, clopidogrel, compared to antiplatelet naïve and patients receiving only aspirin. It is not surprising that clopidogrel enhanced the inhibition of SFLLRN-induced aggregation by vorapaxar because ADP amplifies the response of agonists that degranulate the platelet. The latter property may also explain the slower recovery to baseline in the degree of inhibition of SFLLRN-induced aggregation by vorapaxar, greater bleeding in our study in those treated with clopidogrel, and greater bleeding in the large-scale clinical trial.8 Previous studies have shown that the inhibition of SFLLRN-induced platelet aggregation at a level of 50% can be expected at 4 weeks after discontinuation of daily doses of vorapaxar 2.08 mg, consistent with the terminal elimination half-life of vorapaxar in plasma of 5–13 days.6 However, our results suggest that the level of platelet inhibition may be more pronounced at 30 days of offset, with persistence of ~75%−90% inhibition of PAR-1-dependent platelet aggregation. Additionally, it is likely that vorapaxar, when combined with P2Y12 inhibitors, achieves a synergistic effect on the inhibition SFLLRN-stimulated platelet aggregation instead of an additive effect as observed in patients naïve to antiplatelet therapy or receiving aspirin alone (Figure 2). Given that plasma half-life (t½) of vorapaxar is up to 13 days and almost complete PAR-1 inhibition was observed after nearly four platelet lifecycles (~8 × 4 days), we hypothesize that sustained inhibition of PAR-1 may be the result of megakaryocyte uptake/retention of vorapaxar and engagement of (apo)PAR-1 on nascent platelets.21 It is unlikely that vorapaxar is exerting a persistent off target/downstream effect on aggregation as other platelet agonists including ADP and collagen were not affected before or during the 30-day recovery phase.

Thromboxane production is also known to amplify the platelet-activating response for primary agonists such as collagen and thrombin. Thromboxane A2 has been reported to require ADP to influence platelet function.22 We can speculate that the modification of the response to SFLLRN early by vorapaxar is seen only in the presence of aspirin + clopidogrel, whereas at 24 hours, when drug levels are higher, only inhibition of P2Y12 is potent enough to modify the response.20

Currently, despite FDA approval and improvement in the residual risk of atherothrombotic events in patients on standard antiplatelet therapy, the clinical uptake of vorapaxar has been limited.8 The latter observation may be partially explained by an increased bleeding risk associated with vorapaxar when administered on top of dual antiplatelet therapy. In the two major investigations of vorapaxar, TRA 2P and TRACER, vorapaxar was administered on top of standard antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel. Most of the patients in these two trials received DAPT. In both trials vorapaxar was associated with increased bleeding. In the acute coronary syndrome (ACS) study, the bleeding risk was prohibitive, and the sponsor did not further pursue an indication in this population. The target population for vorapaxar administration are patients with high residual thrombotic risk and low bleeding risk with a history of MI and PAD. This risk potentially may be offset by attenuating the pharmacodynamic effect by a reduction in the frequency of vorapaxar administration. At this time, the degree of inhibition of SFLLRN-induced aggregation that confers clinical benefit is unknown. The extent of PAR-1 inhibition that we observed in the current study was profound after 30 days of daily vorapaxar treatment, and in the presence of added P2Y12 blockade we observed 29% (9/31) minor/nuisance bleeding. Conversely, there was no (0/50) minor/nuisance bleeding in the vorapaxar ± aspirin groups over the 60-day period. In the TRACER trial, patients treated with clopidogrel had greater GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding compared to those treated with aspirin alone. Our pharmacodynamics observations are consistent with these findings.

In this regard, a trial designed to determine the clinical effects of vorapaxar on top of aspirin alone has not been conducted in patients with high-risk vascular disease. This dual therapy may strike a favorable balance in attenuating the risk of ischemia while also reducing bleeding. Moreover, given the sustained inhibition of platelet aggregation by vorapaxar observed in our study when co-administered with P2Y12 inhibitors, a reduction in the frequency of chronic vorapaxar administration (eg, once weekly) may achieve equivalent antssithrombotic effects without the same degree of bleeding as observed in previous studies where the drug was administered daily.5

An absence of effects on viscoelasticity may be explained by the extent of thrombin generated by kaolin in the thromboelastography assay. Despite high level inhibition of PAR-1 by vorapaxar, thrombin-mediated platelet function by PAR-4, the low affinity thrombin receptor, may determine clot viscoelastic properties measured by thrombelastography.4,23

Interestingly, vorapaxar was also shown to have an anti-inflammatory/antiplatelet activation effect as demonstrated by a significant reduction in 11-dhTxB2 levels in patients not on aspirin. Urinary TxB2 is a marker of total in vivo TxA2 generation. TxA2 can be directly generated by activated platelets and through transcellular synthesis in platelets of precursor eicosanoid generated in inflammatory cells. Concomitant aspirin therapy, as a potent COX-1 inhibitor, appeared to eliminate any ability to observe anti-inflammatory/anstiplatelet activation effects induced by vorapaxar in our study. In the antiplatelet-naïve group, however, an effect was observed. An anti-inflammatory effect of vorapaxar has only been described previously in a study of 16 healthy volunteers with experimental endotoxemia induced by lipopolysaccharide infusion.24 PAR-1 inhibition was associated with a dampened peak concentration of tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, and consequently C-reactive protein by 66%, 50%, and 23%, respectively.24 However, no study has explored the anti-inflammatory effects of vorapaxar in a real-world scenario in patients treated with antiplatelet therapy. Interestingly, the anti-inflammatory effect of vorapaxar was attenuated in patients on aspirin therapy suggesting potential shared or opposing pathways of anti-inflammatory effect between aspirin and vorapaxar. Further studies are needed to evaluate the clinical significance of the anti-inflammatory effect observed with vorapaxar in the current study.

4.1 |. Limitations

The present study was an open-label exploratory study with a low power. However, we believe this to be the largest pharmacodynamics study conducted to date assessing the effect of vorapaxar when added to mono- and dual-antiplatelet therapy. Thus, this was an exploratory pharmacodynamic investigation upon which we can build a set of investigations for adequate power. Second, the study design did not incorporate a healthy volunteer group to allow for comparisons of clot kinetics and viscoelasticity, platelet and endothelial function, and inflammation to the study group. Finally, pharmacodynamic assessments were performed after a short duration of drug treatment. Extrapolation of these data to long-term clinical effects requires further investigation. Threshold determinations for each agonist after each treatment would have further contributed to our understanding of the comparative pharmacodynamics effects in each of the groups. In future studies, it would also be important to directly compare clopidogrel alone to vorapaxar alone in addition to clopidogrel plus vorapaxar to assess effects on hemostasis that may indicate risk of bleeding and effects on ischemic events.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

In this first comprehensive assessment, vorapaxar was found to have no influence on clot viscoelasticity or endothelial function irrespective of concomitant antiplatelet therapy. PAR-1 inhibition onset by vorapaxar was accelerated by clopidogrel and offset is prolonged by concomitant antiplatelet therapy. Vorapaxar induced anti-inflammatory effects in non-aspirin-treated patients. Accelerated and potentiated antiplatelet effects by clopidogrel may explain greater bleeding observed in clinical trials. Future studies investigating the mechanism of prolonged inhibition in nascent platelets are warranted. Potential change in drug dosage, frequency, and strategy to improve net clinical benefit may enhance the safety profile and drug efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Essentials.

Vorapaxar is recommended with antiplatelet therapy (APT) in patients with a history of MI and/or PAD.

We evaluated measures of clotting, inflammation, and endothelial function in patients on mono-and dual-APT.

Vorapaxar had no influence on clot characteristics, coagulation, or endothelial function irrespective of APT.

The effect of vorapaxar on PAR-1 platelet inhibition was accelerated and prolonged by concomitant APT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge Tenzin Dechen BSN RN, MPH; Katherine Armstrong, BS; and Kevin Nguyen, BS for their contributions to this study.

Funding information

The study was supported by a grant from Merck.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Gurbel reports serving as a consultant or receiving honoraria for lectures, consultations, including service on speakers’ bureaus from Bayer, Merck, Janssen, Medicure, and World Medical; receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health, Janssen, Merck, Bayer, Haemonetics, Instrumentation Labs, and Amgen. Dr. Gurbel holds stock or stock options in Merck, Medtronic, and Pfizer; and holds patents in the area of personalized antiplatelet therapy and interventional cardiology. Dr. Navarese reports honoraria and payment for lectures from Astra Zeneca, Daiichi Sankyo/Lilly, Sanofi-Regeneron, and Amgen; receiving grants from Amgen. Kevin Bliden, Rahul Chaudhary, Athan Kuliopulos, Henry Tran, Hamid Taheri, Behnam Tehrani, Arnold Rosenblatt, and Udaya S. Tantry report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gurbel PA, Tantry US. Combination antithrombotic therapies. Circulation. 2010;121:569–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tantry US, Bonello L, Aradi D, et al. Consensus and update on the definition of on-treatment platelet reactivity to adenosine diphosphate associated with ischemia and bleeding. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:2261–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tantry US, Navarese EP, Myat A, Chaudhary R, Gurbel PA. Combination oral antithrombotic therapy for the treatment of myocardial infarction: recent developments. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19:653–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badr Eslam R, Lang IM, Koppensteiner R, Calatzis A, Panzer S, Gremmel T. Residual platelet activation through protease-activated receptors (PAR)-1 and −4 in patients on P2Y12 inhibitors. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:403–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tantry US, Liu F, Chen G, Gurbel PA. Vorapaxar in the secondary prevention of atherothrombosis. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;13:1293–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosoglou T, Reyderman L, Tiessen RG, et al. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of the novel PAR-1 antagonist vorapaxar (formerly SCH 530348) in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;68:249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker RC, Moliterno DJ, Jennings LK, et al. Safety and tolerability of SCH 530348 in patients undergoing non-urgent percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II study. Lancet. 2009;373:919–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrow DA, Braunwald E, Bonaca MP, et al. Vorapaxar in the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1404–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fala L. Zontivity (Vorapaxar), first-in-class PAR-1 antagonist, receives FDA approval for risk reduction of heart attack, stroke, and cardiovascular death. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2015;8:148–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zontivity (vorapaxar) Package Insert. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Tantry US, et al. First report of the point-of-care TEG: a technical validation study of the TEG-6S system. Platelets. 2016;27:642–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Chaudhary R, et al. Antiplatelet effect durability of a novel, 24-hour, extended-release prescription formulation of acetylsalicylic acid in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118:1941–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milos M, Herak D, Kuric L, Horvat I, Zadro R. Evaluation and performance characteristics of the coagulation system: ACL TOP analyzer - HemosIL reagents. Int J Lab Hematol. 2009;31:26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bliden KP, Singla A, Gesheff MG, et al. Statin therapy and thromboxane generation in patients with coronary artery disease treated with high-dose aspirin. Thromb Haemost. 2014;112:323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi JL, Kim BR, Woo KS, et al. The diagnostic utility of the point-of-care CYP2C19 genotyping assay in patients with acute coronary syndrome dosing clopidogrel: comparison with platelet function test and SNP genotyping. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2016;46: 489–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Guyer K, et al. Platelet reactivity in patients and recurrent events post-stenting: results of the PREPARE POST-STENTING Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1820–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin KM, Covic L, Kuliopulos A. Matrix metalloproteases and PAR1 activation. Blood. 2013;121:431–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bliden KP, Tantry US, Gesheff MG, et al. Thrombin-induced plate-let-fibrin clot strength identified by thrombelastography: a novel prothrombotic marker of coronary artery stent restenosis. J Interv Cardiol. 2016;29:168–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Saucedo JF, et al. Bivalirudin and clopidogrel with and without eptifibatide for elective stenting: effects on platelet function, thrombelastographic indexes, and their relation to periprocedural infarction results of the CLEAR PLATELETS-2 (Clopidogrel with Eptifibatide to Arrest the Reactivity of Platelets) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(8):648–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraft WK, Gilmartin JH, Chappell DL, et al. Effect of vorapaxar alone and in combination with aspirin on bleeding time and platelet aggregation in healthy adult subjects. Clin Transl Sci. 2016;9:221–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez-Rivera JA, Monedero-Campo J, Cieza-Borrella C, Ruiz-Perez P. Pharmacokinetic drug evaluation of vorapaxar for secondary prevention after acute coronary syndrome. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13:339–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhavaraju K, Georgakis A, Jin J, et al. Antagonism of P2Y12 reduces physiological thromboxane levels. Platelets. 2010;21:604–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorsam RT, Kunapuli SP. Central role of the P2Y12 receptor in platelet activation. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:340–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoergenhofer C, Schwameis M, Gelbenegger G, et al. Inhibition of protease-activated receptor (PAR1) reduces activation of the endothelium, coagulation, fibrinolysis and inflammation during human endotoxemia. Thromb Haemost. 2018;118:1176–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.