Abstract

Background:

An association between productive cytomegalovirus infection and atherosclerosis was shown recently in several trials, including a previous study of ours. However, the mechanism involved in this association is still under investigation. Here, we addressed the interaction between productive cytomegalovirus infection and endothelial function in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

Methods:

We analyzed the presence of cytomegaloviral DNA in plasma and endothelial function in 33 patients with STEMI and 33 volunteers without cardiovascular diseases, using real-time polymerase chain reaction and a noninvasive test of flow-mediated dilation.

Results:

Both the frequency of presence and the load of cytomegaloviral DNA were higher in plasma of STEMI patients than those in controls. This difference was independent of the other cardiovascular risk factors (7.38 [1.36–40.07]; p=0.02). The results of the flow-mediated dilation test were lower in STEMI patients than in controls (5.0 [2.65–3.09]% vs 12.5 [7.5–15.15]%; p=0.004) and correlated negatively with the cytomegaloviral DNA load (Spearman R =−0.407; p=0.019) independently of other cardiovascular risk factors.

Conclusions:

Productive cytomegalovirus infection in STEMI patients correlated negatively with endothelial function independently of other cardiovascular risk factors. The impact of cytomegalovirus on endothelial function may explain the role of cytomegalovirus in cardiovascular prognosis.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus, ST-elevation myocardial infarction, endothelial function, flow-mediated vasodilation, polymerase chain reaction

Introduction

The role of immune system activation in atherosclerotic plaque destabilization and rupture, the major cause of acute coronary syndrome, is well established1,2. However the triggers of immunoactivation in atherosclerosis remain controversial. Among the possible proposed agents are various bacterial and viral infections3–6, whose chronic persistence corresponds to chronic inflammation within plaques7,8. The impact of herpesviruses and in particular of cytomegalovirus (human herpesvirus type 5) on atherosclerosis has been shown in animal models8–11. However, clinical studies based on sero-epidemiological data or viral DNA presence within the artery wall were far less conclusive12–14. At the same time, investigation of a productive cytomegalovirus infection by viral DNA in blood plasma and viral RNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells found a strong positive correlation to the development of acute coronary syndrome15,16. In the current study, we investigated the mechanisms of impact of cytomegalovirus on a major atherosclerotic complication, STEMI. Earlier in in vitro studies it had been shown that cytomegalovirus infects endothelial cells and activates T lymphocyte migration into plaques, causing endothelial dysfunction17–20, which worsens the cardiovascular prognosis of STEMI patients21,22. We found that productive cytomegalovirus infection negatively correlates with endothelial function in STEMI patients. This correlation may explain the role of cytomegalovirus in cardiovascular prognosis that was found in the previous studies23–25.

Materials and Methods

A total of 33 volunteers without cardiovascular diseases (14 men and 19 women, mean age 49.9±7.6 years) and 33 patients with STEMI (28 men and 5 women, mean age 58.6±10.2 years), diagnosed according to the current guidelines26, were enrolled in our study. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for STEMI patients and volunteers without cardiovascular diseases

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| STEMI patients | STEMI diagnosis at the moment of admission according to the guidelines | For STEMI patients: • Time from symptoms onset > 24 hours • Bleeding or necessity of blood/plasma transfusion • Thrombolytic therapy • Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation • Cardiogenic shock • Infusion of nitrates For all participants: • Age below 40 • Acute infections • Neoplasms • Pregnancy |

| Volunteers without cardiovascular diseases | No signs of possible atherosclerosis according to treadmill-test, echocardiography, and ultrasound of peripheral arteries |

STEMI – ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

In both groups we analyzed traditional cardiovascular risk factors according to the established criteria: sex, age, smoking, dyslipidemia (fasting LDL-cholesterol level>160 mg/dL or total cholesterol level>200 mg/dL and HDL-cholesterol level<40 mg/dL), obesity (BMI≥30 kg/m2), arterial hypertension (systolic blood pressure≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure≥90 mmHg), diabetes mellitus (glycated hemoglobin>6.5% or fasting glucose level>7 mmol/l)27, and elevated high sensitive CRP level (hs-CRP>2 mg/l)28

The study protocol and participants’ consent were approved by the Interuniversity Committee of Ethics; all participants signed their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Cytomegaloviral DNA measurement

Peripheral blood samples were obtained from patients at admission before coronary angiography and from controls at the time of examination. Blood was centrifuged at 3,000 g for 15 minutes. We extracted viral DNA from plasma using the viral DNA spin protocol QIAamp UltraSense Virus kit. Detection of cytomegalovirus was performed by means of quantitative real-time PCR on a Bio-Rad thermal cycler CFX 96 C1000 using primer/probe sets for cytomegalovirus and human endogenous retrovirus 3 (ERV-3)29 (Table 2). Load of cytomegalovirus was expressed as copy number of cytomegaloviral DNA per 1 ml of plasma. The specificity of the PCR reaction was confirmed with purified cytomegalovirus as positive control and with human cord blood DNA as negative control. The threshold level of 1,000 copies of cell-free cytomegaloviral DNA per 1 ml of plasma was used as a categorical parameter of the presence of highly productive cytomegalovirus infection30.

Table 2.

Sequences of primers/probes

| Sequence Name | Sequence | Five Modification | Three Modification |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERV-3 Probe | Aacatgggagaccaatggccatggg | Quasar 705* | BHQ |

| ERV-3 Forward | Gttgcttcatgttatgtctgtgg | ||

| ERV-3 Reverse | Ggcggttagtgtgaaattatcttg | ||

| CMV Probe | Tacctggagtccttctgcgagga | CAL Fluor Red 610* | BHQ |

| CMV Forward | Aaccaagatgcaggtgatagg | ||

| CMV Reverse | Agcgtgacgtgcataaaga |

Quasar 705 and Cal Fluor Red 610 are fluorescent dyes.

ERV-3 - human endogenous retrovirus 3; CMV – cytomegaloviral; BHQ - black hole quencher.

Measurement of flow-mediated dilation

We examined flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery using a high resolution ultrasound procedure according to the current guidelines31. The flow-mediated dilation test was performed in STEMI patients at admission before coronary angiography and in controls without cardiovascular diseases at the time of examination. The threshold level of 10% for the result of the flow-mediated dilation test was used as a categorical parameter of the presence of endothelial dysfunction32.

Statistical analyses

The data obtained in the present study were not normally distributed and are represented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). For the comparison of two groups we used the Mann-Whitney rank test. For the analysis of categorical parameters, frequency of endothelial dysfunction and presence of highly productive cytomegalovirus infection we used the Chi-square test with 2×2 contingency tables. For the analysis of correlations, Spearman’s coefficient of correlation was estimated. For the age distribution we made the assumption of its normality and analyzed it using the t-test for two groups. We also performed multiple binomial logistic regression analysis. For this, we used dichotomized age ≥55 years for males and ≥65 years for females and hs-CRP level ≥2 mg/L28 as well as other binominal factors as predictors. The results for regression analysis are presented as odds ratio (OR) ±95% confidence interval (CI). We performed statistical analysis using Statistica 12.0. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We found that the control group was different from the STEMI group in age/sex characteristics as well as in traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, hypertension and hs-CRP level (Table 3). Therefore we assessed further data using multiple logistic regression analysis.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of patients with STEMI and volunteers without cardiovascular diseases

| STEMI patients | Volunteers without cardiovascular diseases | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 33 | 33 | |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 58.6 ± 10.2 | 49.9 ± 7.6 | 0.0028* |

| Men, N (%) | 28 (84.9) | 14 (42.4) | 0.0003* |

| Smoking, N (%) | 24 (72.7) | 5 (15.2) | 0,0000* |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 21 (63.6) | 10 (30.3) | 0.0067* |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 5 (15.2) | 1 (3.0) | 0.0868 |

| Dyslipidemia, N (%) | 9 (27.3) | 4 (12.1) | 0.1218 |

| Obesity, N (%) | 10 (30.3) | 15 (45.5) | 0.2045 |

| hs-CRP level (mg/l), median [IQR] | 4.14 [1.75–8.15] | 1.65 [0.62–2.93] | 0.0004* |

Data are presented as mean ± SD, medians [interquartile ranges] or as number (percentage) of patients.

Differences are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

STEMI – ST-elevation myocardial infarction; hs-CRP –high sensitive C-reactive protein level.

Analysis of cytomegalovirus infection

To evaluate productive viral infection, we measured cytomegaloviral DNA in plasma33. In our measurements cord blood samples were negative for the presence of cytomegalovirus, therefore we analyzed all the positive results for cytomegaloviral DNA load. However, we set additionally an arbitrary level of 1,000 copies of viral DNA per 1 ml of plasma as a threshold for the presence of highly productive cytomegalovirus infection30.

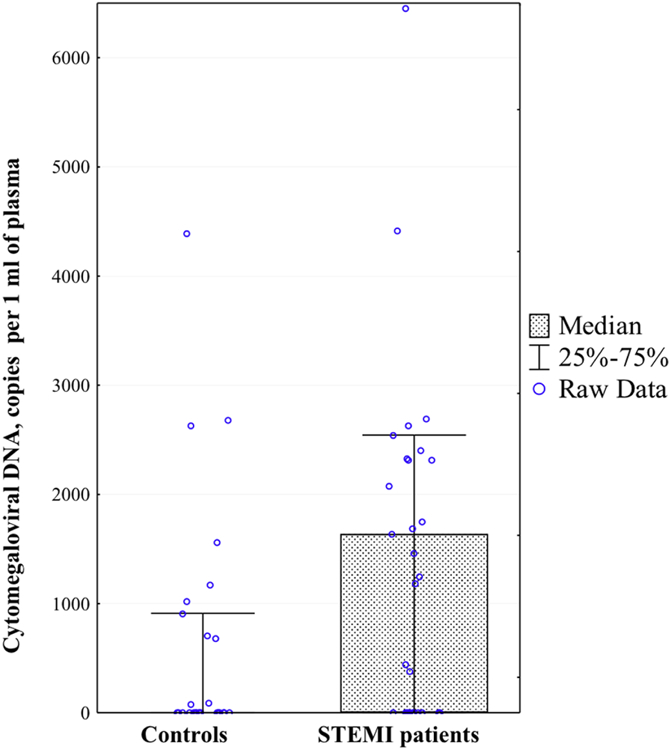

The frequency of presence of highly productive cytomegalovirus infection was higher in plasma of STEMI patients than in plasma of volunteers without cardiovascular diseases (60.6% vs. 24.2%, respectively; p=0.028). The amount of cytomegaloviral DNA was also significantly higher in STEMI patients than in volunteers without cardiovascular diseases (1,638.64[0–2,543.42] vs. 0[0–910.79]; p=0.011) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cytomegaloviral DNA loads in controls and STEMI patients.

Presented are the medians and interquartile range of the amounts of cytomegaloviral DNA copies per 1ml of plasma for volunteers without cardiovascular diseases and patients with STEMI.

* Differences are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

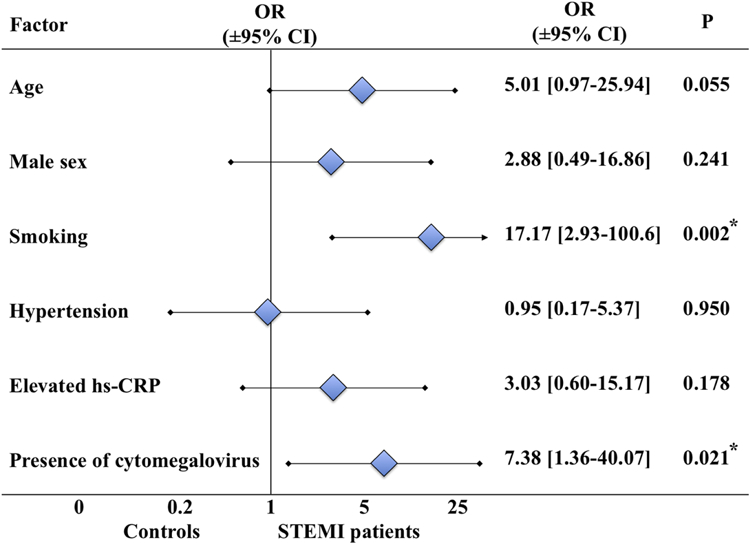

Since our groups differ in several traditional risk factors, we analyzed whether productive cytomegalovirus infection correlate with these factors (Table 4). We found that plasma cytomegaloviral DNA load was higher in hypertensive subjects (1,688.1[0–2,631.8] vs. 0[0–967.0] copies/ml; p=0.013). However, the presence of highly productive cytomegalovirus infection did not correlate with the other cardiovascular risk factors. Only when we analyzed separately cytomegalovirus-positive cases we found a positive correlation of cytomegaloviral DNA load with patients’ age (N=35, Spearman R=0.456; p=0.006). To establish whether productive cytomegalovirus infection is an independent predictor for STEMI or depends on the cardiovascular risk factors, different between two groups, we performed a multiple binomial logistic regression analysis of STEMI development with such predictors as age, sex, smoking, hypertension, and elevated hs-CRP level and with presence of highly productive cytomegalovirus infection as an additional predictor. We found that presence of cytomegalovirus and smoking independently predict the development of STEMI in the multiple regression model (OR[95%CI], respectively, 7.38[1.36–40.07], p=0.021; 17.17[2.93–100.62]; p=0.002), while age, sex, hypertension, and elevated hs-CRP level showed a non-significant, but also substantial, increase in the odds ratios of STEMI development (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Interactions between cytomegaloviral DNA load or presence and cardiovascular risk factors in all participants

| Risk factor | Presence of the risk factor | Absence of the risk factor | p-value(load) / p-value(presence) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMV DNA copies/ml, Me [IQR] | CMV presence, N (%) | CMV DNA copies/ml, Me [IQR] | CMV presence, N (%) | ||

| Male sex | 409.6 [0–2,311.2] | 18 (42.9) | 35.6 [0–1,942.6] | 10 (41.6) | 0.827/0.925 |

| Smoking | 1,185.7 [0–2,327.6] | 15 (51.7) | 0 [0–1,688.1] | 13 (35.1) | 0.212/0.176 |

| Hypertension | 1,688.1 [0–2,631.8] | 19 (61.3) | 0 [0–967.0] | 9 (25.7) | 0.013*/0.004* |

| Diabetes mellitus | 844.0 [0–1,728.8] | 3 (50.0) | 228.9 [0–2,335.7] | 25 (41.7) | 0.853/0.694 |

| Dyslipidemia | 445.0 [0–2,311.4] | 6 (46.2) | 71.1 [0–2,310.5] | 22 (41.5) | 0.702/0.761 |

| Obesity | 0 [0–1,554.0] | 8 (32.0) | 910.8 [0–2,327.6] | 20 (48.8) | 0.158/0.181 |

Presented are the amounts of cytomegaloviral DNA copies per 1 ml of plasma and the percentages of cytomegaloviral DNA presence in plasma in all participants, with the presence or absence of different cardiovascular risk factors. Data are presented as medians [interquartile ranges] of copies of cytomegaloviral DNA and as number (percentage) of cytomegalovirus-positive patients.

Differences are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

CMV – cytomegaloviral; DNA – deoxyribonucleic acid.

Figure 2. Multiple logistic regression analysis of cardiovascular risk factors and presence of cytomegalovirus in STEMI patients and controls.

Presented are the odds ratios for binomial cardiovascular risk factors (with age ≥ 55 years for males and ≥ 65 years for females, and hs-CRP level ≥2 mg/l) and the presence of productive cytomegalovirus infection (>1,000 copies of DNA/ml of plasma) in the multiple regression model for comparison of STEMI patients and volunteers without cardiovascular diseases.

* Differences are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Analysis of endothelial function

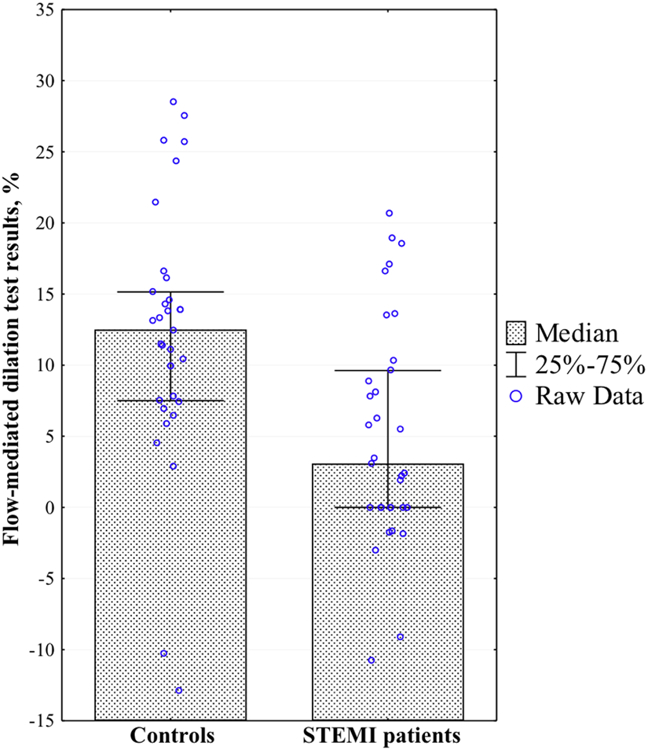

We evaluated endothelial function using the flow-mediated dilation test. In STEMI patients, the flow-mediated dilation test results were significantly lower than those in the control group (5.0[2.65–3.09]% vs 12.5[7.5–15.15]%; p=0.004) (Figure 3). As well, the frequency of endothelial dysfunction was also significantly higher in STEMI patients than in volunteers without cardiovascular diseases (78.8% vs. 36.4%; p=0.0005).

Figure 3. Flow-mediated dilation test results in controls and STEMI patients.

Presented are the medians and interquartile ranges of the flow-mediated dilation test results in volunteers without cardiovascular diseases and patients with STEMI.

* Differences are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Since our groups of participants differed in several risk factors, we analyzed whether flow-mediated dilation test results correlated with them. We found that flow-mediated dilation test results were lower in hypertensive subjects (5.8[0–11.0]% vs 11.4[6.1–15.6]%; p=0.016), and correlated negatively with patients’ age and hs-CRP level (respectively, N=66, Spearman R=−0.355; p=0.004; N=66, Spearman R=−0.409, p=0.0007). There was a tendency for lower flow-mediated dilation test results in men, which was in accordance with previous studies34; however, in our study it did not reach statistical significance (Table 5). In our participants endothelial function also did not correlate with smoking, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, or obesity.

Table 5.

Interactions between endothelial function and cardiovascular risk factors in all participants

| Risk factor | Presence of the risk factor | Absence of the risk factor | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow-mediated dilation test result (%), Me [IQR] | |||

| Male sex | 7.7 [0–13.6] | 11.5 [6.2–16.3] | 0.052 |

| Smoking | 8.2 [0–13.6] | 10.0 [4.6–14.0] | 0.286 |

| Hypertension | 5.8 [0–11.0] | 11.4 [6.1–15.6] | 0.016* |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.2 [0.5–8.1] | 9.2 [3.1–14.0] | 0.258 |

| Dyslipidemia | 7.8 [3.1–13.5] | 10.0 [2.2–14.0] | 0.924 |

| Obesity | 11.4 [4.6–14.6] | 7.5 [0–13.5] | 0.252 |

Data are presented as medians [interquartile ranges] of flow-mediated dilation test results.

Differences are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

To establish whether endothelial dysfunction is an independent predictor for STEMI or depends on the other risk factors, we performed a multiple binomial logistic regression analysis of STEMI development with endothelial dysfunction as an additional predictor. We found that endothelial dysfunction and smoking independently predict the development of STEMI in the multiple regression model (OR[95%CI], respectively, 8.76[1.49–51.52], p=0.016; 27.46[4.16–181.12]; p=0.0006), while age, sex, hypertension, and elevated hs-CRP level showed non-significant changes in the odds ratio of STEMI development (Table 6).

Table 6.

Multiple logistic regression analysis of cardiovascular risk factors and endothelial dysfunction impact for STEMI patients and controls comparison

| Factor | Odds ratio | −95% CI | +95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 3.41 | 0.68 | 17.16 | 0.137 |

| Male sex | 1.00 | 0.19 | 5.22 | 0.997 |

| Smoking | 27.46 | 4.16 | 181.12 | 0.001* |

| Hypertension | 2.26 | 0.34 | 14.93 | 0.399 |

| Elevated hs-CRP level | 1.40 | 0.23 | 8.51 | 0.714 |

| Endothelial dysfunction | 8.76 | 1.49 | 51.52 | 0.016* |

Presented are the odds ratios for binomial cardiovascular risk factors (with age ≥ 55 years for males and ≥ 65 years for females, and hs-CRP level ≥2 mg/l) and the presence of endothelial dysfunction (flow-mediated dilation test result <10%) in the multiple regression model for comparison of STEMI patients and volunteers without cardiovascular diseases.

Differences are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

STEMI – ST-elevation myocardial infarction; hs-CRP –high sensitive C-reactive protein level.

Correlation of productive cytomegalovirus infection with endothelial function

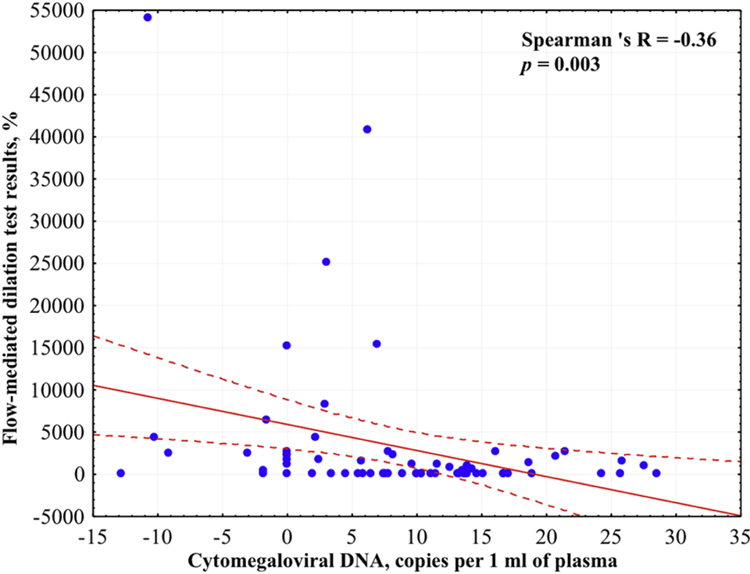

We assessed the correlation between cytomegaloviral DNA loads and flow-mediated dilation test results in both groups together and separately. We found that cytomegaloviral DNA level negatively correlates with flow-mediated dilation test results in all participants (Figure 4), as well as in patients with STEMI (respectively, N=66, Spearman R=−0.360, p=0.003; N=33, Spearman R=−0.407, p=0.019). However, cytomegaloviral DNA loads in controls didn’t correlate significantly with flow-mediated dilation test results.

Figure 4. Correlation between cytomegaloviral DNA loads and flow-mediated dilation test results.

Presented is the correlation with 95% confidential interval according to Spearman Rank test between cytomegaloviral DNA loads and flow-mediated dilation test results in all participants.

* Correlation is statistically significant at p < 0.05.

In view of the correlations of flow-mediated dilation test results and loads of cytomegaloviral DNA with cardiovascular risk factors found in our study, we investigated whether productive cytomegalovirus infection is an independent predictor for endothelial dysfunction or depends on the other risk factors. We found that presence of cytomegalovirus independently predicts the development of endothelial dysfunction in the multiple regression model (OR[95%CI], 3.48 [1.06–11.37]; p = 0.039), while age, sex, hypertension, and elevated CRP level didn’t show significant changes in the odds ratios (Table 7).

Table 7.

Multiple logistic regression analysis of impact of cardiovascular risk factors and presence of cytomegalovirus for comparison of patients with and without endothelial dysfunction

| Factor | Odds ratio | −95% CI | +95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 2.42 | 0.66 | 8.92 | 0.185 |

| Male sex | 2.65 | 0.76 | 9.17 | 0.125 |

| Hypertension | 0.51 | 0.12 | 2.11 | 0.351 |

| Elevated hs-CRP level | 2.36 | 0.70 | 8.00 | 0.167 |

| Presence of cytomegalovirus | 4.10 | 1.19 | 14.05 | 0.025* |

Presented are the odds ratios for binomial cardiovascular risk factors (with age ≥ 55 years for males and ≥ 65 years for females, and hs-CRP level ≥2 mg/l) and the presence of productive cytomegalovirus infection (>1000 copies of DNA/ml of plasma) in the multiple regression model for comparison of patients with and without endothelial dysfunction (defined as flow-mediated dilation test result <10%).

Differences are statistically significant at p < 0.05.

hs-CRP –high sensitive C-reactive protein level.

In summary, we found that (i) the presence and the load of cytomegaloviral DNA in plasma was higher in STEMI patients than in controls, independently of cardiovascular risk factors; (ii) the presence of endothelial dysfunction was higher in STEMI patients than in controls, independently of cardiovascular risk factors; (iii) cytomegaloviral DNA load independently negatively correlates with flow-mediated dilation test results.

Discussion

The destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques and development of recurrent cardiovascular events are strongly associated with activation of the immune system1,2,35,36. The perturbation of T cell repertoire with higher expression of effector memory and activation markers was found not only in blood of patients with cardiovascular diseases but also within their atherosclerotic plaques37.

These data may indicate the presence of a specific antigen(s) towards which these lymphocytes are reactive3–6. Herpes viruses are one of the main candidates causing persistent immunoactivation within plaques due to their ubiquity and ability to cycle between dormancy and replication7,8. Thus, it has been shown that accumulation of intermediate-and late-differentiated T effector memory cells in blood is associated with cytomegalovirus infection38–40.

The first evidence of a relation of herpes viruses to atherosclerosis was found early in 1980s in chickens with Marek’s herpesviral disease9 and was later confirmed through use of various other animal models8,10,11. Moreover, in a number of experimental studies infection of vascular endothelial cells by cytomegalovirus was associated with the progression of atherosclerosis. Thus, replication of cytomegalovirus in endothelial cells and macrophages41 trigger the release of proinflammatory cytokines, adhesion molecules, and matrix metalloproteinases, as well as cellular death11,42–46. While cytokines and adhesion molecules cause CD4 and CD8 T lymphocyte and platelet migration to the subendothelium44,46–48, matrix metalloproteinases cause plaque fibrotic cap destabilization49, altogether leading to the development of acute coronary syndrome. Moreover, in experimental studies it was found that cytomegalovirus infection can lead to severe endothelial dysfunction50,51 and altered response to oxidized lipids in the subendothelium52, leading to atherosclerosis progression.

However, the transition from experimental settings to clinical studies resulted in a contradiction. Analysis of the cytomegaloviral DNA distribution in the human vascular wall revealed a relatively low prevalence of viral DNA in the walls of the aorta and coronary arteries, both in patients who died from atherosclerosis12 and in those who died from other causes53. However, in further studies, cytomegaloviral DNA was found more often in arteries of patients with different complications of atherosclerosis4,54,55 independently of the presence of the other infectious agents56.

Evaluation of the immune response to cytomegalovirus infection initially didn’t reveal an effect of seropositivity to cytomegalovirus on the development of atherosclerosis13,14,63. However, the results of sero-epidemiological studies were also controversial, with further studies, that found a positive correlation between the increased titer of antibodies to cytomegalovirus and the development of atherosclerosis23–25,57,58, cardiovascular events59,60 and mortality61,62, even when adjusted to other traditional cardiovascular risk factors. These controversies in sero-epidemiological studies as well as the low level of cytomegaloviral DNA found in atherosclerotic plaques and later in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with cardiovascular diseases64 could be explained by the occasional detection of the latent infection in these studies, rather than productive viral infection, while only the latter correlates with plaque destabilization65,66.

Accordingly, it was shown that only the detection of the products of replication of cytomegalovirus (viral RNA) or isolation of viral DNA in blood plasma could be reliable signs of productive infection33. S. Gredmark et al. found that the amounts of early RNA genes of cytomegalovirus in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with acute coronary syndrome were higher than those of patients with chronic coronary artery disease and of healthy volunteers15.

In our previous work, we evaluated cytomegaloviral DNA in plasma and showed that productive cytomegalovirus infection is more common in patients with acute coronary syndrome than in patients with chronic coronary artery disease and healthy volunteers. Moreover, in that work we also found a positive correlation between the cytomegaloviral DNA load and T-lymphocyte differentiation within the atherosclerotic plaques of patients with cardiovascular diseases16. This result is in agreement with the studies on differentiation of effector T lymphocytes in blood of patients infected with cytomegalovirus19,20,38–40.

Here, we showed that the presence of cytomegaloviral DNA in plasma of STEMI patients was significantly higher than in volunteers without cardiovascular diseases. These data confirm the results of our previous study and are also in agreement with a meta-analysis, which shows a significant correlation between the concentration of antibodies to cytomegalovirus and the risk of developing of cardiovascular diseases, both in prospective and retrospective analysis24.

Also, we found a significant prevalence in the number of copies of cytomegaloviral DNA in older hypertensive patients, which correspond to the previous studies that showed the positive correlation of antibodies to cytomegalovirus and cytomegaloviral microRNA with arterial blood pressure, especially in elderly patients38,67,68. Moreover, one of the possible mechanisms of the development of hypertension in patients with cytomegalovirus infection could be the development of endothelial dysfunction with the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines and renin by endothelial cells infected with cytomegalovirus69.

Endothelial function plays an important role in patients with atherosclerosis70. Severe endothelial dysfunction in patients with STEMI compared with healthy volunteers has been reported71. Here, we showed that flow-mediated dilation test results were an independent risk factor of STEMI, corresponding to the results of other trials21,22,72. Also, in this study, we confirmed that endothelial function is impaired more significantly in older patients with elevated levels of hs-CRP73.

An interaction between endothelial dysfunction and cytomegalovirus infection was initially found in clinical studies of healthy volunteers74,75. However, these data were not consistent76. Later, J. Simmonds and P. Petrakopoulou found a negative correlation between cytomegaloviral DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and endothelial function in patients after heart transplantation77,78.

We demonstrated here for the first time the negative correlation between productive cytomegalovirus infection and endothelial function in patients with STEMI (alone and together with the volunteers without cardiovascular diseases). This result could be explained by the impact of cytomegalovirus infection on the synthesis of an inhibitor of endothelial NO-synthase and the blockade of NO-synthase activation17,18. Also, the effect of cytomegalovirus on endothelial function can be caused by the release of effector Т cells with receptors to fractalkine19,20 – a chemokine, causing endothelial cell activation and apoptosis, abolished by antibodies to these receptors79. In a multivariate analysis, we confirmed that the identified correlation persisted, regardless of sex, hypertension, CRP level, and patient age - factors that were significantly associated with production of cytomegalovirus and endothelial function.

In summary, we found that cytomegalovirus infection is strongly associated with endothelial dysfunction in STEMI patients.

Our work has significant limitations: the frequencies of presence of some risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, and dyslipidemia in both groups were so low that there were perhaps too few events to support these variables in the simple or multiple regression model; also, while the release of cytomegalovirus into the blood is accepted as evidence of productive infection we do not know which specific cells produce cytomegalovirus and whether these cells are localized in plaques or at other sites.

Although we found an association between the cytomegalovirus in plasma and endothelial dysfunction, it is possible that other pathogens, not studied in the present work, may also associate with this pathological state. In general, our results support a hypothesis that acute coronary events are synchronized with replication of cytomegalovirus, and this viral reactivation contributes to endothelial dysfunction. Therefore, it is conceivable that preventing the reactivation of cytomegalovirus may enhance endothelial function and affect the outcome of coronary artery disease.

Future studies should shed more light on the relation of cytomegalovirus infection to endothelial dysfunction in STEMI in particular and to cardiovascular diseases in general and may lead to new treatment strategies.

Productive cytomegalovirus infection is present more often in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction than in volunteers without cardiovascular disease independently of cardiovascular risk factors.

Productive cytomegalovirus infection correlated negatively with endothelial function in STEMI patients.

The correlation of cytomegaloviral DNA in plasma with endothelial dysfunction is independent of other cardiovascular risk factors.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Barry Alpher for assistance in editing and improving the English style.

Funding Sources: The work of A.L., E.M., A.S., and E.V was supported by Russian Science Foundation, agreement #18-15-00420. The work of L.M. and J-C.G. was supported by the Intramural Program of National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hartvigsen K, Chou M-Y, Hansen LF, et al. The role of innate immunity in atherogenesis. J Lipid Res 2008;50(Supplement):S388–S393. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800100-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Libby P, Tabas I, Fredman G, Fisher EA. Inflammation and its resolution as determinants of acute coronary syndromes. Circ Res 2014;114(12):1867–1879. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenfeld ME, Campbell LA. Pathogens and atherosclerosis: Update on the potential contribution of multiple infectious organisms to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost 2011;106(5):858–867. doi: 10.1160/TH11-06-0392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Espinola-Klein C, Rupprecht HJ, Blankenberg S, et al. Impact of infectious burden on extent and long-term prognosis of atherosclerosis. Circulation 2002;105(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libby P, Loscalzo J, Ridker PM, et al. Inflammation, Immunity, and Infection in Atherothrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72(17):2071–2081. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pothineni NVK, Subramany S, Kuriakose K, et al. Infections, atherosclerosis, and coronary heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017;38(43):3195–3201. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stassen FR, Vega-Córdova X, Vliegen I, Bruggeman CA. Immune activation following cytomegalovirus infection: More important than direct viral effects in cardiovascular disease? J Clin Virol 2006;35(3):349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krebs P, Scandella E, Bolinger B, Engeler D, Miller S, Ludewig B. Chronic Immune Reactivity Against Persisting Microbial Antigen in the Vasculature Exacerbates Atherosclerotic Lesion Formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007;27(10):2206–2213. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabricant CG, Fabricant J, Minick CR, Litrenta MM. Virus-induced atherosclerosis. J Exp Med 1978;148(1):335–340. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.1.335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsich E, Zhou YF, Paigen B, Johnson TM, Burnett MS, Epstein SE. Cytomegalovirus infection increases development of atherosclerosis in Apolipoprotein-E knockout mice. Atherosclerosis 2001;156(1):23–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vliegen I, Herngreen SB, Grauls GELM, Bruggeman CA, Stassen FRM. Mouse cytomegalovirus antigenic immune stimulation is sufficient to aggravate atherosclerosis in hypercholesterolemic mice. Atherosclerosis 2005;181(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xenaki E, Hassoulas J, Apostolakis S, Sourvinos G, Spandidos DA. Detection of Cytomegalovirus in Atherosclerotic Plaques and Nonatherosclerotic Arteries. Angiology 2009;60(4):504–508. doi: 10.1177/0003319708322390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siscovick DS, Schwartz SM, Corey L, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae, herpes simplex virus type 1, and cytomegalovirus and incident myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease death in older adults : the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation 2000;102(19):2335–2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adler SP, Hur JK, Wang JB, Vetrovec GW. Prior infection with cytomegalovirus is not a major risk factor for angiographically demonstrated coronary artery atherosclerosis. J Infect Dis 1998;177(1):209–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gredmark S, Jonasson L, Van Gosliga D, Ernerudh J, Söderberg-Nauclér C. Active cytomegalovirus replication in patients with coronary disease. Scand Cardiovasc J 2007;41(4):230–234. doi: 10.1080/14017430701383755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikitskaya E, Lebedeva A, Ivanova O, et al. Cytomegalovirus- Productive Infection Is Associated With Acute Coronary Syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc 2016;5(8):e003759. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.003759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weis M, Kledal TN, Lin KY, et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection Impairs the Nitric Oxide Synthase Pathway: Role of Asymmetric Dimethylarginine in Transplant Arteriosclerosis. Circulation 2004;109(4):500–505. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109692.16004.AF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen Y, Zhang L, Utama B, et al. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits Akt-mediated eNOS activation through upregulating PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10). Cardiovasc Res 2006;69(2):502–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van de Berg PJEJ, Yong S-L, Remmerswaal EBM, van Lier RAW, ten Berge IJM. Cytomegalovirus-Induced Effector T Cells Cause Endothelial Cell Damage. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012;19(5):772–779. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00011-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pachnio A, Ciaurriz M, Begum J, et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection Leads to Development of High Frequencies of Cytotoxic Virus-Specific CD4+ T Cells Targeted to Vascular Endothelium. Kalejta RF, ed. PLOS Pathog 2016;12(9):e1005832. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu Y, Arora RC, Hiebert BM, et al. Non-invasive endothelial function testing and the risk of adverse outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Hear J -Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;15(7):736–746. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdel Hamid M, Bakhoum SW, Sharaf Y, Sabry D, El-Gengehe AT, Abdel-Latif A. Circulating Endothelial Cells and Endothelial Function Predict Major Adverse Cardiac Events and Early Adverse Left Ventricular Remodeling in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Interv Cardiol 2016;29(1):89–98. doi: 10.1111/joic.12269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haider AW, Wilson PWF, Larson MG, et al. The association of seropositivity to Helicobacter pylori, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and cytomegalovirus with risk of cardiovascular disease: a prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;40(8):1408–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ji Y-N, An L, Zhan P, Chen X-H. Cytomegalovirus infection and coronary heart disease risk: a meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep 2012;39(6):6537–6546. doi: 10.1007/s11033-012-1482-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jia Y, Liu J, Han F, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection and atherosclerosis risk: A meta-analysis. J Med Virol 2017;89(12):2196–2206. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2018;39(2):119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agostino RBD, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117(6):743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, et al. Reduction in C-reactive protein and LDL cholesterol and cardiovascular event rates after initiation of rosuvastatin: a prospective study of the JUPITER trial. Lancet (London, England) 2009;373(9670):1175–1182. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60447-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yuan CC, Miley W, Waters D. A quantification of human cells using an ERV-3 real time PCR assay. J Virol Methods 2001;91(2):109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kraft CS, Armstrong WS, Caliendo AM. Interpreting quantitative cytomegalovirus DNA testing: understanding the laboratory perspective. Clin Infect Dis 2012;54(12):1793–1797. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thijssen DHJ, Black MA, Pyke KE, et al. Assessment of flow-mediated dilation in humans: a methodological and physiological guideline. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011;300(1):H2–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00471.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sancheti S, Shah P, Phalgune DS. Correlation of endothelial dysfunction measured by flow-mediated vasodilatation to severity of coronary artery disease. Indian Heart J 2018;70(5):622–626. doi: 10.1016/J.IHJ.2018.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gimeno C, Solano C, Latorre JC, et al. Quantification of DNA in plasma by an automated real-time PCR assay (cytomegalovirus PCR kit) for surveillance of active cytomegalovirus infection and guidance of preemptive therapy for allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. J Clin Microbiol 2008;46(10):3311–3318. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00797-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel AR, Kuvin JT, Sliney KA, et al. Gender-based differences in brachial artery flow-mediated vasodilation as an indicator of significant coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 2005;96(9):1223–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.06.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liuzzo G, Biasucci LM, Trotta G, et al. Unusual CD4+CD28null T lymphocytes and recurrence of acute coronary events. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50(15):1450–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ammirati E, Cianflone D, Vecchio V, et al. Effector Memory T cells Are Associated With Atherosclerosis in Humans and Animal Models. J Am Heart Assoc 2012;1(1):27–41. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grivel J-C, Ivanova O, Pinegina N, et al. Activation of T lymphocytes in atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2011;31(12):2929–2937. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.237081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terrazzini N, Bajwa M, Vita S, et al. A Novel Cytomegalovirus-Induced Regulatory-Type T-Cell Subset Increases in Size During Older Life and Links Virus-Specific Immunity to Vascular Pathology. J Infect Dis 2014;209(9):1382–1392. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Betjes MGH, de Wit EEA, Weimar W, Litjens NHR. Circulating pro-inflammatory CD4posCD28null T cells are independently associated with cardiovascular disease in ESRD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25(11):3640–3646. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang F-J, Shu K-H, Chen H-Y, et al. Anti-cytomegalovirus IgG antibody titer is positively associated with advanced T cell differentiation and coronary artery disease in end-stage renal disease. Immun Ageing 2018;15(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12979-018-0120-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jarvis MA, Nelson JA. Human cytomegalovirus persistence and latency in endothelial cells and macrophages. Curr Opin Microbiol 2002;5(4):403–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Straat K, de Klark R, Gredmark-Russ S, Eriksson P, Soderberg-Naucler C. Infection with Human Cytomegalovirus Alters the MMP-9/TIMP-1 Balance in Human Macrophages. J Virol 2009;83(2):830–835. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01363-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lunardi C, Dolcino M, Peterlana D, et al. Endothelial Cells’ Activation and Apoptosis Induced by a Subset of Antibodies against Human Cytomegalovirus: Relevance to the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis. Papavasiliou N, ed. PLoS One 2007;2(5):e473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popović M, Smiljanić K, Dobutović B, Syrovets T, Simmet T, Isenović ER. Human cytomegalovirus infection and atherothrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2012;33(2):160–172. doi: 10.1007/s11239-011-0662-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen K, Xu L, Chen D, Tang W, Huang Y. Human cytomegalovirus-encoded miR-UL112 contributes to HCMV-mediated vascular diseases by inducing vascular endothelial cell dysfunction. Virus Genes 2018;54(2):172–181. doi: 10.1007/s11262-018-1532-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waldman WJ, Knight DA, Huang EH. An in vitro model of T cell activation by autologous cytomegalovirus (CMV)-infected human adult endothelial cells: contribution of CMV-enhanced endothelial ICAM-1. J Immunol 1998;160(7):3143–3151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bolovan-Fritts CA, Trout RN, Spector SA. High T-cell response to human cytomegalovirus induces chemokine-mediated endothelial cell damage. Blood 2007;110(6):1857–1863. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-078881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rahbar A, Soderberg-Naucler C. Human Cytomegalovirus Infection of Endothelial Cells Triggers Platelet Adhesion and Aggregation. J Virol 2005;79(4):2211–2220. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.4.2211-2220.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abbas A, Aukrust P, Russell D, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 7 is associated with symptomatic lesions and adverse events in patients with carotid atherosclerosis. PLoS One 2014;9(1):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khoretonenko MV, Leskov IL, Jennings SR, Yurochko AD, Stokes KY. Cytomegalovirus Infection Leads to Microvascular Dysfunction and Exacerbates Hypercholesterolemia-Induced Responses. Am J Pathol 2010;177(4):2134–2144. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gombos RB, Brown JC, Teefy J, et al. Vascular dysfunction in young, mid-aged and aged mice with latent cytomegalovirus infections. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013;304(2):H183–H194. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00461.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carlquist JF, Muhlestein JB, Horne BD, et al. Cytomegalovirus stimulated mRNA accumulation and cell surface expression of the oxidized LDL scavenger receptor, CD36. Atherosclerosis 2004;177(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamashiroya HM, Ghosh L, Yang R, Robertson AL. Herpesviridae in the coronary arteries and aorta of young trauma victims. Am J Pathol 1988;130(1):71–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horváth R, Cerný J, Benedík J, Hökl J, Jelínková I. The possible role of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) in the origin of atherosclerosis. J Clin Virol 2000;16(1):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu R, Moroi M, Yamamoto M, et al. Presence and severity of Chlamydia pneumoniae and Cytomegalovirus infection in coronary plaques are associated with acute coronary syndromes. Int Heart J 2006;47(4):511–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Izadi M, Zamani MM, Sabetkish N, et al. The probable role of cytomegalovirus in acute myocardial infarction. Jundishapur J Microbiol 2014;7(3):e9253. doi: 10.5812/jjm.9253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sorlie PD, Nieto FJ, Adam E, Folsom AR, Shahar E, Massing M. A prospective study of cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus 1, and coronary heart disease: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Arch Intern Med 2000;160(13):2027–2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang H, Peng G, Bai J, et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection and Relative Risk of Cardiovascular Disease (Ischemic Heart Disease, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Death): A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies Up to 2016. J Am Heart Assoc 2017;6(7). doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.005025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Epstein SE, Zhou YF, Zhu J. Potential role of cytomegalovirus in the pathogenesis of restenosis and atherosclerosis. Am Heart J 1999;138(5 Pt 2):S476–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Timóteo A, Ferreira J, Paixão P, et al. Serologic markers for cytomegalovirus in acute coronary syndromes. Rev Port Cardiol 2003;22(5):619–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roberts ET, Haan MN, Dowd JB, Aiello AE. Cytomegalovirus antibody levels, inflammation, and mortality among elderly Latinos over 9 years of follow-up. Am J Epidemiol 2010;172(4):363–371. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu J, Nieto FJ, Horne BD, Anderson JL, Muhlestein JB, Epstein SE. Prospective study of pathogen burden and risk of myocardial infarction or death. Circulation 2001;103(1):45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Stampfer MJ, Wang F. Prospective study of herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and the risk of future myocardial infarction and stroke. Circulation 1999;98(25):2796–2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schlitt A, Blankenberg S, Weise K, et al. Herpesvirus DNA (Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus) in circulating monocytes of patients with coronary artery disease. Acta Cardiol 2005;60(6):605–610. doi: 10.2143/AC.60.6.2004932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Prince HE, Lapé-Nixon M. Role of cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgG avidity testing in diagnosing primary CMV infection during pregnancy. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2014;21(10):1377–1384. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00487-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gerna G, Percivalle E, Baldanti F, et al. Human cytomegalovirus replicates abortively in polymorphonuclear leukocytes after transfer from infected endothelial cells via transient microfusion events. J Virol 2000;74(12):5629–5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Firth C, Harrison R, Ritchie S, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with an increase in systolic blood pressure in older individuals. QJM 2016;109(9):595–600. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcw026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li S, Zhu J, Zhang W, et al. Signature microRNA Expression Profile of Essential Hypertension and Its Novel Link to Human Cytomegalovirus Infection. Circulation 2011;124(2):175–184. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.012237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cheng J, Ke Q, Jin Z, et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection Causes an Increase of Arterial Blood Pressure. Früh K, ed. PLoS Pathog 2009;5(5):e1000427. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gimbrone MA, García-Cardeña G. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction and the Pathobiology of Atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2016;118(4):620–636. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Manchurov V, Ryazankina N, Khmara T, et al. Remote ischemic preconditioning and endothelial function in patients with acute myocardial infarction and primary PCI. Am J Med 2014;127(7):670–673. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yeboah J, Folsom AR, Burke GL, et al. Predictive value of brachial flow-mediated dilation for incident cardiovascular events in a population-based study: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation 2009;120(6):502–509. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.864801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang P-H, Chen J-W, Lu T-M, Yu-An Ding P, Lin S-J. Combined use of endothelial function assessed by brachial ultrasound and high-sensitive C-reactive protein in predicting cardiovascular events. Clin Cardiol 2007;30(3):135–140. doi: 10.1002/clc.20058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grahame-Clarke C, Chan NN, Andrew D, et al. Human Cytomegalovirus Seropositivity Is Associated With Impaired Vascular Function. Circulation 2003;108(6):678–683. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000084505.54603.C7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Haarala A, Kähönen M, Lehtimäki T, et al. Relation of high cytomegalovirus antibody titres to blood pressure and brachial artery flow-mediated dilation in young men: The Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Clin Exp Immunol 2012;167(2):309–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04513.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khairy P, Rinfret S, Tardif J-C, et al. Absence of Association Between Infectious Agents and Endothelial Function in Healthy Young Men. Circulation 2003;107(15):1966–1971. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000064895.89033.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Simmonds J, Fenton M, Dewar C, et al. Endothelial Dysfunction and Cytomegalovirus Replication in Pediatric Heart Transplantation. Circulation 2008;117(20):2657–2661. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.718874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Petrakopoulou P, Kübrich M, Pehlivanli S, et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection in Heart Transplant Recipients Is Associated With Impaired Endothelial Function. Circulation 2004;110(11_suppl_1):II-207–II-212. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138393.99310.1c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bolovan-Fritts CA, Spector SA. Endothelial damage from cytomegalovirus-specific host immune response can be prevented by targeted disruption of fractalkine-CX3CR1 interaction. Blood 2008;111(1):175–182. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]