Abstract

Background:

A molecular basis for VWF self-inhibition has been proposed by which the N- and C-terminal flanking sequences of the globular A1 domain disulfide loop bind to and suppress the conformational dynamics of A1. These flanking sequences are rich in O-linked glycosylation (OLG) which is known to suppress platelet adhesion to VWF, presumably by steric hinderance. The inhibitory mechanism remains unresolved as to whether inhibition is due to steric exclusion by OLG’s or a direct self-association interaction that stabilizes the domain.

Objectives:

The platelet adhesive function, thermodynamic stability, and conformational dynamics of the wild-type and type 2M G1324S A1 domain lacking glycosylation (E.coli) are compared with the wild-type glycosylated A1 domain (HEK293 cell culture) to decipher the self-inhibitory mechanism.

Methods:

SPR and analytical rheology are utilized to assess GPIbα binding at equilibrium and platelet adhesion under shear flow. The conformational stability is assessed through a combination of protein unfolding thermodynamics and HXMS.

Results:

A1 glycosylation inhibits both GPIbα binding and platelet adhesion. Glycosylation increases the hydrodynamic size of A1. Glycosylation stabilizes the thermal unfolding of A1 without changing its equilibrium stability. Glycosylation does not alter the intrinsic conformational dynamics of the A1 domain.

Conclusions:

These studies invalidate the proposed inhibition through conformational suppression since glycosylation within these flanking sequences does not alter the native state stability or the conformational dynamics of A1. Rather, they confirm a mechanism by which glycosylation sterically hinders platelet adhesion to the A1 domain at equilibrium and under rheological shear stress.

Keywords: Glycosylation, Steric Exclusion, Conformational Dynamics, Thermodynamic Stability

3. Introduction.

The Von Willebrand Factor (VWF) is an enormous multimeric plasma glycoprotein responsible for capturing platelets and initiating primary hemostasis at sites of vascular injury. Approaching many mega-Daltons in molecular weight, multimers of VWF consist of a complex architecture of repeat A, C and D domains (D’D3 A1A2A3 D4 C1–C6 CK) in the monomeric unit (~2000 residues, ~250kDa) which is dimerized tail-to-tail at C-terminal cysteine knot (CK) domains and multimerized head-to-head at N-terminal D’ domains [1, 2]. Within the monomeric unit, glycosylation makes up ~20% of the mass of VWF [3, 4], 30% of which is O-linked glycosylation (OLG). While N-linked glycosylation (NLG) is distributed throughout the various C and D domains of VWF [4, 5] as well as A2 [6], OLG’s are highly localized to the platelet GPIbα adhesive A1 domain N- and C-terminal peptide linkers flanking the domain between D3 and A1 and between A1 and A2.

For three decades since the identification of a tryptic fragment of VWF containing the A1 domain [7], the N- and C-terminal flanking sequences outside the disulfide loop of A1 have been implicated to modulate the platelet adhesive function of VWF [8]. Yet, the issue of how these flanking sequences regulate A1 function continually resurfaces throughout the years as new experimental methods become available to probe VWF structure/function relationships. Initially, synthetic peptides comprising residues C1237-P1251 and L1457- P1471 displayed a weak capacity, requiring 10’s to 100’s of μM concentrations, to inhibit ristocetin dependent binding of native VWF to platelet GPIbα [8]. Later, recombinant strategies that truncated these flanking sequences from the A1 domain indicated an enhanced GPIbα interaction [9–11], but single molecule atomic force spectroscopy measurements contradicted these studies by showing that an N-terminal truncation of A1 decreased the bond lifetime between A1 and GPIbα at high force [12]. Site directed mutagenesis of threonine and serine residues consistently demonstrated that removal of OLG’s from these sequences within their natural context enhances the interaction between VWF and platelet GPIbα both in the absence and presence of shear flow [13–15]. These studies support a mechanism by which OLG’s sterically inhibit VWF platelet interactions by shielding access to the A1 domain by GPIbα. However, the issue has once again become confounded by truncation studies in combination with hydrogen-deuterium exchange that propose a cooperative autoinhibitory interaction between the N- and C-terminal flanking sequences with the globular domain structure that modulates the conformational dynamics of A1 [16, 17].

It is established that mutations causing Von Willebrand Disease (VWD) alter the intrinsic conformational dynamics and stability of the A1 domain and even cause locally disordered misfolded states of A1 within multimeric VWF [18–27]. The hypothesis to be addressed here, is whether these flanking sequences inhibit the A1-GPIbα interaction indirectly through steric exclusion via glycosylation [15] or through a direct interaction that alters the intrinsic conformational dynamics of the A1 domain [16,17]. To address the issue, we illustrate a simple comparison of A1 expressed in E.coli with glycosylated A1 expressed in HEK293 cell culture. Surface plasmon resonance and analytical rheology are utilized to assess platelet binding function at equilibrium and under shear flow, respectively. The structure and stability are assessed through a combination of thermodynamics and hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HXMS). A type 2M G1324S VWD variant of E.coli A1 is included to reference a true loss-of-function due to stabilization and suppression of A1 conformational dynamics [21].

The presence of glycosylation is observed to inhibit the A1-platelet GPIbα interaction in agreement with prior studies [15]. While glycosylation stabilizes thermal unfolding of A1, it does not appreciably change its urea denaturation equilibrium stability or its intrinsic hydrogen-deuterium exchange. These thermodynamic results mean that glycosylation destabilizes the unfolded state without affecting the stability or conformational dynamics of the folded state, and thus invalidate the proposed autoinhibition hypothesis. Glycosylation significantly increases the hydrodynamic radius of A1 and, in light of the thermodynamic results, it is concluded that the inhibition is purely a consequence of physical steric exclusion that restricts platelet GPIbα access to the A1 domain. The principles of this study are further considered in the context of VWD.

4. Results.

The nonglycosylated WT A1 domain and the type 2M G1324S VWD variant of VWF were expressed in E.coli. Glycosylated WT A1 was obtained from expression in HEK293 cell culture. These three variants are compared with regards to their platelet binding function (Fig.1), hydrodynamic size and thermodynamic stability (Fig.2), and conformational dynamics assessed by HXMS (Fig.3) in the following sections.

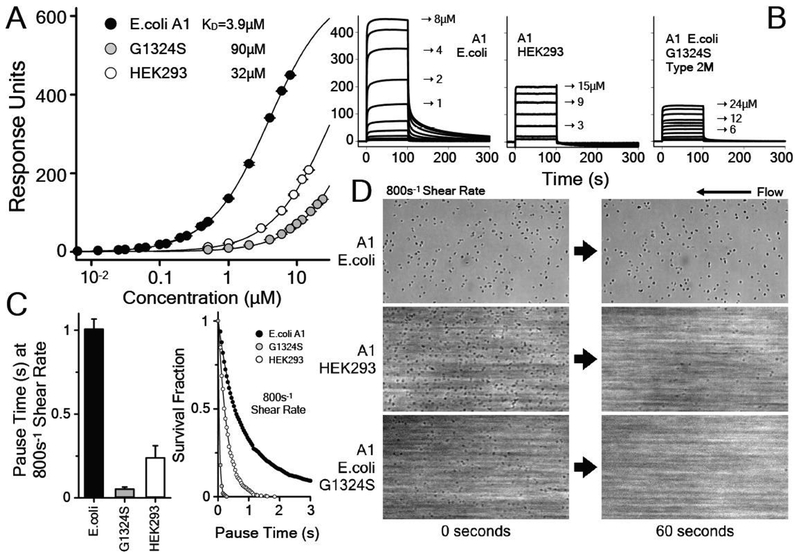

Figure 1:

A) Equilibrium binding of WT A1 (E.coli), Type 2M G1324S A1 (E.coli) and WT A1 (HEK293) to platelet GPIbα. Binding curves (SPR response as a function of A1 concentration. Each point on these curves represents the maximum response observed (panel B) after injection of a defined concentration of A1. Apparent KD (3.9±0.1μM) for A1 (E.coli), (32±1) for A1 (HEK293), and (90±2) for A1 G1324S (E.coli). SPR response at maximum saturation is Rmax = 670±10. B) Representative SPR binding traces as a function of A1 concentration. C) Average platelet pause times at 800s−1 shear rate (left) and corresponding survival fractions (right) on immobilized WT A1 (E.coli), Type 2M G1324S A1 (E.coli) and WT A1 (HEK293). D) Representative platelet translocation on immobilized WT A1 (E.coli), Type 2M G1324S A1 (E.coli) and WT A1 (HEK293) at 0s and 60s time-points in a single experiment, see movies in online supporting information. Overall, these data demonstrate that glycosylation is inhibitory to GPIbα binding and to platelet adhesion under shear flow. It should be emphasized that the trend in binding affinity as given by the apparent KD obtained by SPR is the same as the trend in platelet pause times and survival fraction under shear flow obtained by analytical rheology. That is, the KD for G1324S A1 > glycosylated HEK293 A1 > nonglycosylated E.coli A1. Likewise, the platelet pause times for nonglycosylated E.coli A1 > glycosylated HEK293 A1 > G1324S A1. I.e. the lower the KD, the higher the GPIbα binding affinity and the platelet pause time. Additionally, this trend is the same regardless of whether the His-tag is located on the C-terminus (HEK293 A1) or the N-terminus (E.coli A1) indicating that the position of the His-tag, far removed from the globular disulfide loop of A1, is not a determining factor for A1 platelet adhesive function.

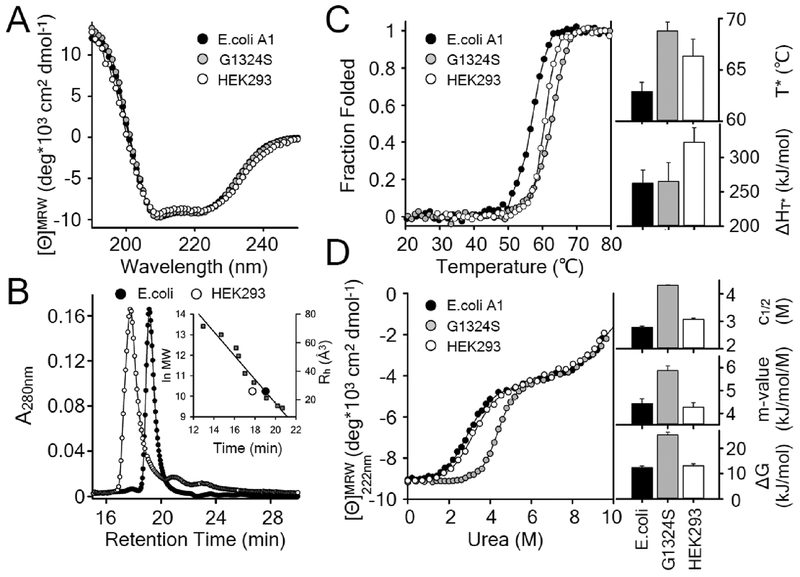

Figure 2:

A) Far-UV CD spectra of WT A1 and Type 2M G1324S A1 (E.coli) and WT A1 (HEK293). B) Size exclusion chromatography of WT A1 expressed from E.coli and HEK293 cell culture. C) Thermal unfolding of each A1 construct monitored by CD with the kinetic thermal transition temperature, T*, and the enthalpy of unfolding, ΔH at the transition temperature. D) Urea denaturation of each A1 construct at 25°C with the free energy, ΔG, cooperativity, m-value, midpoint of the urea denaturation, c1/2. Overall, these data demonstrate that WT A1 expressed in E.coli and in HEK293 cells have the same secondary structure content, as their Far-UV CD spectra are identical, and their equilibrium stability is near identical, as the urea denaturation curves are nearly superimposable. Their macromolecular size and their thermal stability, however, differ substantially as a result of the glycosylation. The enhanced thermal stability, indexed by the increased transition temperature (T*) and enthalpy (ΔH), is a consequence of the glycosylation- induced destabilization of the unfolded state rather than a stabilization of the folded state as described by Shental-Bechore and Levy [28]. Glycosylation does not affect the equilibrium stability of A1, but it does increase the domain’s macromolecular size. These data, combined with the data of Fig.1, indicate that the observed inhibition of GPIbα binding and platelet adhesion to A1 by glycosylation is a consequence of steric hinderance rather than stabilization of the folded state. For reference, the loss-of-function G1324S type 2M VWD variant, known to stabilize A1 [21], increases the midpoint of both the urea and thermal transitions, a net stabilization of the native state. Fig.3 corroborates these conclusions through the measurement of residue specific dynamics by hydrogen exchange. It should be emphasized that these structural and thermodynamic properties of glycosylated and nonglycosylated A1 are independent of the expression construct, small differences in amino acid C-terminal boundaries, or the purification methods [61].

Figure 3:

A) Pepsin and trypsin peptide mapping of WT A1 expressed in E.coli and HEK293 cell culture. Red vertical lines represent the disulfide bond. Magenta vertical lines indicate residues that are O-glycosylated. B) HXMS hydrogen deuterium exchange fraction of each WT A1 construct at 1min, 1hr, and 24hrs. Quenched exchange due to stabilization of A1 by G1324S at 1hr is shown for reference. C) 1hr HX fraction mapped onto the structure of the A1 (pdb ID 1AUQ [68]) is identical in presence and absence of glycosylation. Black = not resolved, blue = 0, white = 0.25, red 0.5. All structures are rendered using UCSF Chimera [69]. D) Peptide envelopes (normalized intensity versus mass shift relative to the “all H” peak) of X peptides covering various secondary structure regions of the A1 domain expressed in E.coli and HEK293 without and with O-glycosylation on the N and C-termini. Relative to the “all H” peptide at zero time, 1hour HX of peptides in each secondary structure region is observed to be the same regardless of the recombinant expression construct. Overall, these data demonstrate that the local conformational dynamics of the A1 domain is unchanged by the presence of glycosylation in the N- and C-terminal flanking peptides. The hydrogen exchange data agree with and support the conclusions derived from Figs.1 & 2. The culmination of these data from all three figures demonstrates that glycosylation sterically inhibits GPIbα binding and platelet adhesion without altering the thermodynamic or local conformational properties of the native state of A1.

4.1. A1 glycosylation inhibits GPIbα binding and platelet adhesion under shear stress.

Surface plasmon resonance was utilized to assess the effect of glycosylation on the equilibrium binding affinity of A1 to GPIbα. Figs.1A&B demonstrates that glycosylation increases the apparent dissociation constant (KD) from 3.9 to 32 μM corresponding to an 8-fold reduction in binding affinity. For reference, the KD of G1324S is 90 μM, a 23-fold reduction in binding affinity.

Analytical Rheology was utilized to assess the effect of glycosylation on platelet adhesion under shear flow at 800s−1 shear rate which produces the maximum pause time observed for WT A1 in our prior publications [19, 23]. This parallel-plate flow-chamber method resulted in many platelets showing the characteristic stick and roll behavior that has been described previously [11, 19–21, 23]. On average, platelet interaction pause times with Cu2+ surface-chelated glycosylated A1 were ~0.25 s, reduced from ~1 s observed for nonglycosylated A1, Fig.1C. For reference, pause times of platelet interactions with G1324S were ~0.1 s. Glycosylation significantly increases the rate of dissociation, Fig.1C resulting in a substantial loss of platelets interacting with the Cu2+-chelated A1 surface over the time of the experiment, 60s (Fig.1D). Quantified by the survival fractions in Fig.1C, movies of the shear flow assays included in the Supporting Information show that while nonglycosylated A1 efficiently supports platelet translocation with minimal loss of platelets, the number of observable platelets decreases dramatically for glycosylated A1 and for G1324S A1 within the length of the recorded movies.

4.2. Glycosylation increases the hydrodynamic radius of A1.

Fig.2A illustrates that WT and G1324S nonglycosylated A1 and WT glycosylated A1 are natively folded with identical far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectra containing significant amounts of α-helical content for which minima at 222 and 208 nm and maxima at 195 nm are characteristic.

Analytical size exclusion chromatography (SEC) is a classical method which distinguishes macromolecular size (calibrated to either known hydrodynamic radii or molecular weights) based upon the partitioning of macromolecules between the mobile phase and a chromatographic matrix of known pore size. Fig.2B demonstrates that the hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of glycosylated A1 (~36.3 Å) is significantly larger than nonglycosylated A1 (~25.4 °A). These values of hydrodynamic radii correspond to apparent molecular weights of ~57.6 kDa and ~27.2 kDa, respectively, based on a simple correlation between molecular weight and hydrodynamic radius (inset of Fig.2B). The molecular weight determined from the hydrodynamic radius of glycosylated A1 is significantly larger than the calculated weight of 31.8 kDa based on amino acid sequence indicating that glycosylation makes up a substantial portion of its molecular mass. In contrast, the molecular weight of nonglycosylated A1 determined from SEC is within experimental error the same as the 28.1 kDa calculated from the sequence.

4.3. Glycosylation stabilizes the thermal unfolding kinetics of A1 without changing its equilibrium stability.

Prior studies have demonstrated that thermal unfolding of A1 is a kinetically controlled irreversible process [11, 21, 27] that makes the apparent thermal transition temperature, TM, dependent on the experimental temperature scan rate. An irreversible unfolding analysis yields a scan rate independent thermal transition temperature, T*, that is corrected for the temperature dependence of the unfolding rate constant [11]. Thermal unfolding of the A1 domains, monitored at 2°C/min via CD at 222 nm (Fig.2C), demonstrates that glycosylation stabilizes WT A1 with both an increase in the transition temperature (T*) from 62.8 to 66.3°C and an increase in the enthalpy (ΔH) of the transition from 262±19 to 322±22 kJ/mol. G1324S unfolds at 68.8°C with an enthalpy equal to that of WT A1, 265±28 kJ/mol.

Urea denaturation of the A1 domains, monitored via CD at 222 nm (Fig.2D), demonstrates that glycosylation has little effect on the equilibrium stability of A1. The midpoint of urea denaturation (c1/2) is only slightly increased from 2.78±0.04 to 3.07±0.05 M and the stability (ΔG) and cooperativity of denaturation (m-value) are unchanged within experimental error. Urea denaturation of G1324S occurs at a much higher urea concentration (4.31±0.02) with a larger cooperativity and, consequently, a higher equilibrium stability. These observations illustrate that glycosylation kinetically stabilizes A1 without altering its equilibrium stability. The effect of glycosylation on the unfolding of A1 is congruent with prior observations of protein stabilizing effects of glycosylation in general [28]. Thermal stabilization by glycosylation stems from a destabilization of the unfolded state rather than a stabilization of the folded state [28]. The higher free energy of the unfolded glycosylated state is enthalpic in origin [29], hence the observed increase in ΔH of thermal unfolding, because steric exclusion caused by glycosylation induces more extended conformations of the unfolded state [28]. The increased enthalpy of the irreversible thermal transition in the presence of glycosylation necessarily results in a kinetic stabilization of the A1 domain. By contrast, the thermodynamic stability obtained by urea denaturation is essentially unaltered. The small increase in c1/2 is a consequence of preferential hydration of A1 caused by the glycans as saccharides are known to preferentially increase the water content at the protein peptide amide groups [30–33] which directly competes with urea hydrogen bonding [34, 35]. Whereas the stabilizing effect of glycosylation on A1 is predominantly exerted on unfolded state, the type 2M G1324S variant of A1 stabilizes the folded state of A1 by restraining the conformation degrees of freedom of the folded state and decreases the probability of local conformational fluctuations necessary for function [21].

4.4. Glycosylation does not alter the intrinsic conformational dynamics of A1.

To determine whether A1 expressed in HEK293 cells has additional glycosylation sites within the A1 domain disulfide loop, peptide maps were generated by pepsin digestion of both glycosylated and nonglycosylated A1. The peptide coverage was similar in both proteins throughout the disulfide loop as indicated by the resulting overlapping peptides, 138 in E.coli A1 and 154 in HEK293 A1 (Fig.3A). Furthermore, A1 is only glycosylated in the N- and C-terminal flanking sequences, but not in the plasmid-derived vector sequences.

Since the pepsin digestion is non-specific at a pH of ~2.7, trypsin digestion was used to further confirm these observations. For the non-specific pepsin digestion of glycosylated A1, no peptides were observed between residues 1245–1270 of the N-terminus or 1465–1481 of the C-terminus. Digestion of glycosylated A1 with trypsin resulted in the absence of the disulfide fragment (Q1238-R1274-S-S-D1451-H1472), which contains the glycosylated regions [36].

Hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry was performed to assess the effect of glycosylation on the intrinsic conformational dynamics of the A1 domain. Fig.3B shows the exchange fraction as a function of A1 domain residue after exposure to D2O for three incubation times, 1 min, 1 hr, and 24 hrs. The 1 hr time-point is mapped to the A1 structure in Fig.3C. Glycosylation of A1 does not alter the hydrogen-deuterium exchange pattern at any of the incubation times since the exchange-fraction is identical within experimental error for both glycosylated and nonglycosylated A1. By contrast, the exchange fraction of the type 2M G1324S A1 variant is significantly lower at 1 hr than both of the WT A1 domains from the β2-β3 hairpin through the α2-α3 helices, confirming the observed increase in thermodynamic stability (Fig.2D) [21]. Individual peptide envelopes throughout the A1 domain secondary structure elements confirm that the hydrogen-deuterium exchange of both glycosylated and nonglycosylated A1 are identical. Thus, glycosylation has no influence on the structural dynamics of the A1 domain that are observable with HXMS.

5. Discussion.

The results of this comparative study demonstrate that the inhibition of platelet adhesion to the A1 domain when glycosylation is present is predominantly a result of steric exclusion. Our results support the conclusions by Nowak et al. that glycosylation simply shields the A1 domain and reduces its accessibility to platelet GPIbα [15]. They do not support the proposal by Deng et al. that the glycosylated N- and C-terminal flanking sequences alter and modulate the intrinsic conformational dynamics of the globular part of the A1 domain within the disulfide loop [16, 17].

The principles of the observed inhibition by glycosylation are borne out in the traditional thermodynamic measurements which demonstrate that the effect of glycosylation on the thermal stability of A1 is a consequence of its action on the unfolded state rather than the natively folded state [28]. Denaturation with urea confirms that the native state stability at equilibrium is unaltered by glycosylation. It should also be noted that these principles also apply to glycosylated and nonglycosylated A2 domain in the absence of calcium as reported by Lynch et al. [6, 37]. HXMS further confirms that the native state conformational dynamics of glycosylated and nonglycosylated A1 domains are not significantly different. The only effect glycosylation has on the native state is to increase the hydrodynamic size of the A1 domain.

Deng et al., have proposed on the basis of HXMS, that the N- and C-terminal glycosylated flanking sequences bind to the A1 domain and directly suppress the dynamics of A1. In order for hydrogen deuterium exchange to be substantially altered by protein-protein association, however, either the existing amide hydrogen bonded network of the proteins must be significantly stabilized or new amide hydrogen bonds must be formed by the interaction. Restrained conformational dynamics is inhibitory to GPIbα binding as has been observed for the type 2M G1324S VWD variant of VWF (Fig.3B) [21]. The comparative studies between glycosylated and nonglycosylated A1 domains reported here demonstrate that the hydrogen deuterium exchange is not altered by the glycosylation in these sequences. Additionally, the hydrogen deuterium exchange of A1 expressed in E.coli is the same as the A1 domain expressed in a glycosylated A1A2A3 tri-domain VWF fragment and the same as the A1 domain present in full-length VWF [18] indicating that the intrinsic conformational dynamics of A1 are not appreciably affected by glycosylation, flanking sequences, or neighboring domains.

In light of our results, the decrease in the thermal transition temperature of N- and C-terminally truncated A1 domains observed by Deng et al. is misinterpreted to be a consequence of the proposed binding of these flanking sequences to the globular disulfide loop of A1 [17]. The thermal stabilization of proteins is known to be due to the overall extent of glycosylation regardless of the types or branching patterns of covalently attached glycans [29], but glycosylation has no effect on the equilibrium stability the folded state. Even in the absence of glycosylation, truncation of the N-terminal flanking sequence of A1 has no effect on either the thermal or equilibrium stability of A1 [11] indicating that any interaction of the flanking sequences with the globular A1 domain is weak at best. The large dissociation constant, KD ~ 50μM, of the association between the N-terminal flanking peptide and the N-terminally truncated A1 confirms the weak binding reported by Mohri et al. [8], and the interaction is likely not as site-specific as was originally claimed [11]. Because of its steric hinderance, glycosylation present in these flanking sequences prevents such an interaction, just as it inhibits the association between A1 and GPIbα, and consequently the hydrogen exchange and the stability of A1 are actually unaffected. That said, it is probable that the stability and quaternary association of the A1, A2, and A3 domains of VWF in an inactive closed conformation is mediated by glycosylation interactions between the various OLG sites in the A1 flanking linker sequences as well as the NLG sites in the A2 domain [10]. This provides a potential explanation for the activation of VWF by ristocetin, an antibiotic macroglycopeptide, that disrupts these interactions [38].

Given the principle of inhibition via steric exclusion, the removal of glycosylation sites from A1 could result in a relative gain-of-function analogous to a type 2B VWD phenotype. Similarly, addition of glycosylation sites to A1 could further inhibit its platelet adhesive capacity resulting in a relative loss-of-function analogous to a type 2M VWD phenotype. Within the N- and C-terminal flanking sequences from Q1238- Y1271 and D1459-M1495, OLG is known to occur at T1248, T1255, T1256, and S1263 in the N-terminus and T1468, T1477, S1486, and T1487 in the C-terminus. Nowak et al. demonstrated that mutating these residues enhances function due to the loss of a glycosylation site. Conversely, Flood et al. reported a mutation which could, “in principle”, add an OLG site. P1467S inhibited binding to platelets and GPIbα in the presence of ristocetin, but as the patient did not experience any clinically significant bleeding, the ristocetin-dependent diagnosis was reported to be spurious [39]. The glycosylated A1 domain reported here lacks the S1486 / T1487 doublet, but mouse studies reported by Badirou et al. show that mutation of these sites does not appreciably alter the plasma VWF level, multimer pattern, bleeding time, or platelet interaction indicating that a limited number of OLG’s are relevant to the biology of VWF [40].

There are, however, no other mutations reported within the A1 domain flanking sequences which would officially implicate altered glycosylation as a cause of VWD or a type 2B gain-of-function phenotype [41]. Although there are type 2 VWD mutations within the globular A1 disulfide loop that remove residues that could be glycosylated, proteolytic digestion of the WT A1 domain expressed in HEK293 cells demonstrates that glycosylation is absent from residues within the disulfide loop of A1 (Fig.3A). Furthermore, any additional glycosylation from mutations that introduce potential N- or O-linked glycosylation sites within the A1 disulfide loop has not been implicated to be the cause of type 2M VWD either [41]. Thus, one might deduce that any inhibition of the A1-GPIbα binding coming from glycosylation is common to both normal and type 2B/2M VWD individuals.

The extent of O-glycosylation and the structures comprising ABH antigens do contribute to VWF activity and VWF antigen levels [42,43] as blood groups have been reported to influence plasma concentration of VWF [44,45]. Specifically, the type O blood group lacking the A and B antigenic terminal carbohydrate N- acetylgalactosamine and D-galactose moieties of glycosylation [46] has a shorter half-life of VWF in plasma [47, 48] relative to A, B, or AB blood groups. The contributing factor is enhanced VWF proteolysis by ADAMTS13 in the type O blood group. This action is further enhanced in the “Bombay” phenotype where A, B, and H antigens are absent from glycosylation [47, 49]. Glycosylation may also affect binding of VWF to clearance receptors, such as LRP1 which binds rheologically exposed A1 domains [50] and disordered type 2B VWD A1 domain variants [51]. From a sterics perspective, glycosylation protects VWF by attenuating these protein-protein interactions that regulate blood plasma levels through physical volume exclusion. That said, however, shear and VWF conformation independent macrophage lectin receptors are also involved in VWF clearance [52, 53].

Under rheological shear stress, untethered VWF concatemers transition from a bird’s nest multimeric coil to an elongated multimeric string that supports platelet adhesion to exposed A1 domains as a result of rotational and elongational forces of blood flow [54–56]. This process of rheological entanglement of VWF with flowing platelets is often implicated in type 2B VWD [11, 12, 16, 57–59] where mutations are presumed to simply disrupt interactions among local sequences and domains that inhibit the activation of VWF [26]. Our studies of type 2B VWD show that mutations destabilize and even misfold the A1 structure [18–20, 23], a consequence much more severe than the disruption of intramolecular quaternary interactions.

In conclusion, glycosylation is inhibitory to platelet adhesion as a result of steric exclusion only and this is likely a common denominator in both health and disease. VWD mutations in VWF cannot alter the rheology of blood flow, but they do alter the intrinsic conformational dynamics of the A1 domain [18–25, 27]. Although glycosylation, or lack thereof, can contribute to shear-dependent VWF activity and clearance in plasma [60], it does not change the conformational dynamics of A1, but rather, merely attenuates the probability of forming a stable bond with platelet GPIbα through steric hinderance. The conformational dynamics of A1 remain poised for action when stable bonds with GPIbα are formed.

6. Methods and Materials.

6.1. Proteins

Wild type GPIbα (amino acids H1 - E285 containing the signal peptide M−15 to Pro0) was expressed in the pIRES neo2 plasmid vector in HEK293 cells as a fusion construct containing an C-terminal FLAG-tag and an C-terminal Hexahistidine-tag.

The wild-type nonglycosylated A1 domain of VWF (Q1238-P1471) and the 2M mutant G1324S were expressed in E.coli M15 cells as fusion proteins containing an N-terminal hexahistidine-tag using BamHI and HindIII restriction sites in the Qiagen pQE-9 plasmid [61]. The plasmid adds the following amino acids to the sequence of A1: MRGSHHHHHHGS-VWFA1(Q1238-P1471)-KLN. The inclusion body isolation, the refolding and purification of the proteins was performed as previously described [23].

Glycosylated A1 domain (Q1238-P1480) was expressed in HEK293 cells as a fusion protein containing a C-terminal hexahistidine-tag using the HindIII and XhoI restriction sites in the Invitrogen pSecTag2B [62]. The vector used for the expression in mammalian cell culture adds the following amino acids to the sequence of A1: DAAQPARRARRTKL-VWF-A1(Q1238-P1480)-ARGGPEQKLISEEDLNSAVDHHHHHH. It is conceivable that the vector derived residues on the N- and C-terminus of A1 here could contribute additional glycosylation sites, but the peptide mapping in Fig.3A demonstrates that these sequences are not glycosylated. The protein was purified via Ni2+ affinity chromatography as previously described. The Protein concentrations were determined on a Shimadzu UV2101PC spectrophotometer using an extinction coefficient of 15350 L/mol/cm for all A1 domains.

All proteins were purified and their quality was confirmed by RP-HPLC and analytical size exclusion chromatography as described previously [61].

6.2. Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy

CD measurements were performed on an Aviv Biomedical Model 420 SF circular dichroism spectrometer. Far UV CD spectra were recorded between 190 and 260 nm using a 0.1 mm quartz cell at 20°C. The step width was 1 nm and the integration time 60 s.

Thermal unfolding was followed at 222 nm using 1 μM protein in a 1 cm quartz cell under slight stirring. After an initial equilibration phase at 20°C the temperature was increased up to 80°C with rates of between 0.5 and 2.0 °C/min. The kinetic thermal transition temperature, T*, and the enthalpy of unfolding, ΔH at the transition temperature were determined as previously described using a two-state irreversible model [11, 27].

Urea induced unfolding was monitored at 222 nm using a 2 mm quartz cell and defined protein concentrations between 3 and 5 μM. All samples were equilibrated overnight at 25°C containing a defined urea concentration. CD signal was averaged for approx. 5 min using an integration time of 1 s. The unfolding was analyzed using a three-state reversible model (N ↔ I ↔ D) as previously described [62].

All spectra and the urea induced unfolding were corrected for the signal of their corresponding buffer and converted to mean ellipticity per amino acid residue (ΘMRW).

6.3. Analytical Size Exclusion Chromatography

Size exclusion chromatography was performed using an analytical Phenomenex SEC-S3000 column on a Beckman System Gold HPLC (pump model 125, UV detector model 166). PBS containing a total of 1M NaCl was used as mobile phase. The flow rate was 0.5 ml/min and the absorbance was monitored at 280 nm. Molecular mass calibration was performed using the following proteins: Thyroglobulin (669 kDa), Ferritin (440 kDa), Catalase (232 kDa), Aldolase (158 kDa), Bovine Serum Albumin (67 kDa), Ovalbumin (43 kDa), Soybean Trypsin inhibitor (20.1 kDa), RNAse (13.7 kDa) and Cytochrome C (12.4 kDa).

6.4. Surface Plasmon Resonance Spectroscopy.

Surface plasmon resonance experiments were performed on a Biacore T-100 system as previously described [20]. GPIbα was immobilized using an Anti-FLAG-tag antibody that was cross-linked to the surface of a CM5 chip (GE Healthcare) via EDC-NHS coupling. Interactions between A1, expressed in E.coli or HEK293 cells, G1324S A1 (with protein concentrations ranging between 6 nM and 24 μM) and GPIbα were measured at 25 °C in HEPES buffer, pH 7.4 at a flow rate of 30 μL/min. For each binding cycle 2 μM GPIbα was loaded for 300 s followed by a 100 s buffer wash phase and the subsequent injection of the ligand. After 100 s, buffer was injected for 200 s and the Anti-FLAG surface was regenerated with an injection of 10 mM glycine, pH 2.0 for 60 s. Sensorgrams were referenced and blank subtracted. Equilibrium responses were plotted as a function of ligand concentration and globally fitted to a simple binding affinity model (equation 1) with a shared maximum instrument response, Rmax. KD is the apparent dissociation constant for the binding.

| (1) |

6.5. Analytical Rheology.

The parallel plate flow assay on immobilized wild type A1 (expressed in E.coli or HEK293 cells) and on the 2M mutant G1324S was performed as previously described [11,20,21,23,24] using Cellix Vena8 CGS biochips on a Zeiss Axio Observer-A1 microscope operated by Zen2012 software. Citrated whole blood was perfused over the Cu2+ chelated proteins at a shear rate of 800 s−1. After 3–4 minutes TBS was perfused through the channel to remove red blood cells. A 60 s video was recorded in phase contrast mode using a PCO.edge camera operated at 25 frames per second. Platelet tracking in the recorded movies was performed using the MediaCybernetics ImagePro Premier software suite. Analysis of the platelet tracks was performed using a Wolfram Mathematica script written in our laboratory [11].

6.6. Limited Proteolysis with Trypsin.

Tryptic proteolysis of A1 expressed in E.coli was performed as previously described [21, 63]. Samples were analyzed by the Mayo Clinic Medical Genome Facility Proteomics core using an Agilent 1200 HPLC system coupled to an Agilent 6224 TOF mass spectrometer. A1 expressed in E.coli or HEK293 cells was concentrated to 33 μM and 300 μL of the protein solution were mixed with 5 μL of 1 mg/mL Trypsin. After an overnight incubation at 37°C, peptide fragments were injected onto a Grace Vydac C18-column coupled to a Beckman System Gold HPLC (pump model 125, UV-detector model 168). The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min using a gradient of 2 % B/min. Water containing 0.1% TFA was used as solvent A and Acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA was used as solvent B. Absorbance of the de-salted and separated tryptic fragments was monitored simultaneously at 220 and 280 nm and 2 mL fractions were collected manually after detection. Samples were injected into an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer and analyzed using the BioWorks 3.3.1 software suite.

6.7. Hydrogen-Deuterium exchange mass spectrometry, HXMS.

HXMS was performed as previously described [20, 64] on A1 (expressed in E.coli or HEK293 cell culture) using a Waters Acquity UPLC coupled to an LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer operated at a resolution of 60000. HX samples were prepared by 1 to 5 dilution of the proteins (in TBS) into TBS in D2O (pD 7.4). After 1 h at 25 °C, the exchange was quenched by a drop in pD to ~2.7. Samples were loaded onto a custom packed pepsin column (3 × 20 mm) under isocratic flow (200 μL/min) of 0.1% formic acid. Peptides were captured by a subsequent C8 column (Higgins Analytical, Targa C8, 40 × 2.1 mm). After 5 min the trap column was switched to a water/acetonitrile gradient. Peptides were eluted from the trap with a flow rate of 20 μL/min, separated on a C18 column (Waters Symmetry C18, 180 μm × 20 mm) and injected into the mass spectrometer.

Prior to HX on both proteins, multiple “all H” experiments were used to generate peptide maps containing a pool of searchable peptides. Not all of the peptides in the pool are guaranteed to be identified in any given experimental measurement. EXMS2 has a variety of filter criteria to remove bad peptides including thresholds on peak envelope noise, intensity range, peptide charge state, envelope fitting, peak retention time, and overlapping peptide mass to charge ratios [65]. For these experiments a small portion of both protein solutions was dialyzed into 0.1% formic acid, pH 2.7 which resulted in the denaturation of both proteins and thus an efficient cleavage by pepsin. Peptide maps were generated using BioWorks 3.3.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the Matlab-based software EXMS2 [20, 65, 66]. The peptide search tolerance was set to 4ppm. Deuterated peptides were identified in EXMS2 with a tolerance of 10 ppm using the previously generated peptide maps as a pool of searchable peptides and the first all-H experiment as reference.

To deconvolve the HX results obtained from EXMS2, HDSite [67] was used with an experimental temperature of 25°C and a pD of 7.4. No back exchange correction was performed. The deuteration range was set to 0.8. After the analysis, switchable peptides were averaged manually.

Supplementary Material

1. Essentials.

VWF self-inhibition is driven by O-linked glycosylation.

Glycosylation does not alter the thermodynamic stability of the A1 domain native conformation.

Glycosylation does not alter the intrinsic conformational dynamics of the A1 domain.

Glycosylation increases A1 domain hydrodynamic size and sterically inhibits platelet adhesion.

7. Acknowledgements.

This study was supported, in part, by research funding from the National Institutes of Health Grant HL109109 from NHLBI, the Mayo Clinic Division of Hematology Small Grants Program (CCaTS UL1TR000135), the Mayo Clinic Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology Collaborative Research Funds, the Mayo Clinic Center for Biomedical Discovery, the Great Lakes Hemophilia Foundation and the Health Resources and Services Administration through the Mayo Clinic Comprehensive Hemophilia Treatment Center.

We thank the technical support from staff of the Mayo Clinic Proteomics Core for technical support with limited trypsinolysis mass spectrometry and analysis.

We also gratefully acknowledge Drs. S. Walter Englander and Leland Mayne for very helpful scientific discussions regarding optimization of HXMS and the establishment of HXMS technology in our lab. In addition, we acknowledge charitable contributions from Mark Davies’ Cycle Von Willebrand Disease, which have defrayed, in part, publication costs.

Abbreviations Used:

- VWF

Von Willebrand Factor

- VWD

Von Willebrand Disease

- OLG

O-Linked Glycosylation

- NLG

N-Linked Glycosylation

- HXMS

Hydrogen Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry

- SPR

Surface Plasmon Resonance

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Disclosure of conflicts of interest.

The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Lippok S, Kolsek K, Löf A, Eggert D, Vanderlinden W, Müller J, König G, Obser T, Röhrs K, Schneppenheim S, Budde U, Baldauf C, Aponte-Santamaría C, Gräter F, Schneppenheim R, Rädler J, and Brehm M, “von Willebrand factor is dimerized by protein disulfide isomerase.,” Blood, vol. 127, no. 9, pp. 1183–1191, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Zhou Y and Springer T, “Highly reinforced structure of a c-terminal dimerization domain in von Willebrand factor.,” Blood, vol. 123, no. 12, pp. 1785–1793, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Millar CM, Riddell AF, Brown SA, Starke R, Mackie I, Bowen DJ, Jenkins PV, and van Mourik JA, “Survival of von Willebrand factor released following DDAVP in a type 1 von Willebrand disease cohort: influence of glycosylation, proteolysis and gene mutations,” Thromb Haemost, vol. 100, no. 05, pp. 916–924, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Millar C and Brown S, “Oligosaccharide structures of von Willebrand factor and their potential role in von Willebrand disease.,” Blood Rev, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 83–92, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Canis K, McKinnon T, Nowak A, Haslam S, Panico M, Morris H, Laffan M, and Dell A, “Mapping the n-glycome of human von Willebrand factor.,” Biochem J, vol. 447, no. 2, pp. 217–228, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lynch C and Lane D, “N-linked glycan stabilization of the vwf a2 domain.,” Blood, vol. 127, no. 13, pp. 1711–1718, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Fujimura Y, Titani K, Holland L, Russell S, Roberts J, Elder J, Ruggeri Z, and Zimmerman T, “von Willebrand factor. a reduced and alkylated 52/48-kda fragment beginning at amino acid residue 449 contains the domain interacting with platelet glycoprotein ib.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 261, no. 1, pp. 381–385, 1986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mohri H, Fujimura Y, Shima M, Yoshioka A, Houghten R, Ruggeri Z, and Zimmerman T, “Structure of the von Willebrand factor domain interacting with glycoprotein ib.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 263, no. 34, pp. 17901–17904, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nakayama T, Matsushita T, Dong Z, Sadler J, Jorieux S, Mazurier C, Meyer D, Kojima T, and Saito H, “Identification of the regulatory elements of the human von Willebrand factor for binding to platelet gpib. importance of structural integrity of the regions flanked by the cys1272-cys1458 disulfide bond.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 277, no. 24, pp. 22063–22072, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Auton M, Sowa K, Behymer M, and Cruz M, “N-terminal flanking region of a1 domain in von Willebrand factor stabilizes structure of a1a2a3 complex and modulates platelet activation under shear stress.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 287, no. 18, pp. 14579–14585, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tischer A, Cruz M, and Auton M, “The linker between the d3 and a1 domains of vwf suppresses a1- gpibα catch bonds by site-specific binding to the a1 domain.,” Protein Sci, vol. 22, no. 8, pp. 1049–1059, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ju L, Dong J, Cruz M, and Zhu C, “The n-terminal flanking region of the a1 domain regulates the force-dependent binding of von Willebrand factor to platelet glycoprotein ibα.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 288, no. 45, pp. 32289–32301, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Schulte am Esch J, Robson S, Knoefel W, Eisenberger C, Peiper M, and Rogiers X, “Impact of o-linked glycosylation of the vwf-a1-domain flanking regions on platelet interaction.,” Br J Haematol, vol. 128, no. 1, pp. 82–90, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Nowak AA, The Role of O-Linked Glycosylation in VWF Function. PhD thesis, Imperial College London, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nowak A, Canis K, Riddell A, Laffan M, and McKinnon T, “O-linked glycosylation of von Willebrand factor modulates the interaction with platelet receptor glycoprotein ib under static and shear stress conditions.,” Blood, vol. 120, no. 1, pp. 214–222, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Deng W, Wang Y, Druzak S, Healey J, Syed A, Lollar P, and Li R, “A discontinuous autoinhibitory module masks the a1 domain of von Willebrand factor.,” J Thromb Haemost, vol. 15, no. 9, pp. 1867–1877, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Deng W, Voos KM, Colucci JK, Legan ER, Ortlund EA, Lollar P, and Li R, “Delimiting the autoinhibitory module of von Willebrand factor,” J Thromb Haemost, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Tischer A, Brehm M, Machha V, Moon-Tasson L, Benson L, Nelton K, Leger R, Obser T, Martinez-Vargas M, Whitten S, Chen D, Pruthi R, Bergen III H, Cruz M, Schneppenheim R, and Auton M, “Evidence for the misfolding of the a1 domain within multimeric von Willebrand factor in type 2 von Willebrand disease,” J Mol Biol, accepted article, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Machha V, Tischer A, Moon-Tasson L, and Auton M, “The von Willebrand factor a1-collagen iii interaction is independent of conformation and type 2 von Willebrand disease phenotype.,” J Mol Biol, vol. 429, no. 1, pp. 32–47, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Tischer A, Machha V, Frontroth J, Brehm M, Obser T, Schneppenheim R, Mayne L, Walter Englander S, and Auton M, “Enhanced local disorder in a clinically elusive von Willebrand factor provokes high-affinity platelet clumping.,” J Mol Biol, vol. 429, no. 14, pp. 2161–2177, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tischer A, Campbell J, Machha V, Moon-Tasson L, Benson L, Sankaran B, Kim C, and Auton M, “Mutational constraints on local unfolding inhibit the rheological adaptation of von Willebrand factor.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 291, no. 8, pp. 3848–3859, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zimmermann M, Tischer A, Whitten S, and Auton M, “Structural origins of misfolding propensity in the platelet adhesive von Willebrand factor a1 domain.,” Biophys J, vol. 109, no. 2, pp. 398–406, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Tischer A, Madde P, Moon-Tasson L, and Auton M, “Misfolding of vwf to pathologically disordered conformations impacts the severity of von Willebrand disease.,” Biophys J, vol. 107, no. 5, pp. 1185–1195, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tischer A, Madde P, Blancas-Mejia L, and Auton M, “A molten globule intermediate of the von Willebrand factor a1 domain firmly tethers platelets under shear flow.,” Proteins, vol. 82, no. 5, pp. 867–878, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Auton M, Zhu C, and Cruz M, “The mechanism of vwf-mediated platelet gpibalpha binding.,” Biophys J, vol. 99, no. 4, pp. 1192–1201, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Auton M, Sowa K, Smith S, Sedlák E, Vijayan K, and Cruz M, “Destabilization of the a1 domain in von Willebrand factor dissociates the a1a2a3 tri-domain and provokes spontaneous binding to glycopro- tein ibalpha and platelet activation under shear stress.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 285, no. 30, pp. 22831–22839, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Auton M, Sedlák E, Marek J, Wu T, Zhu C, and Cruz M, “Changes in thermodynamic stability of von Willebrand factor differentially affect the force-dependent binding to platelet gpibα.,” Biophys J, vol. 97, no. 2, pp. 618–627, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Shental-Bechor D and Levy Y, “Effect of glycosylation on protein folding: a close look at thermodynamic stabilization,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 105, no. 24, pp. 8256–8261, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Wang C, Eufemi M, Turano C, and Giartosio A, “Influence of the carbohydrate moiety on the stability of glycoproteins.,” Biochemistry, vol. 35, no. 23, pp. 7299–7307, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Arakawa T and Timasheff S, “Stabilization of protein structure by sugars.,” Biochemistry, vol. 21, no. 25, pp. 6536–6544, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lee JC and Timasheff SN, “The stabilization of proteins by sucrose.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 256, no. 14, pp. 7193–7201, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Auton M, Ferreon A, and Bolen D, “Metrics that differentiate the origins of osmolyte effects on protein stability: a test of the surface tension proposal.,” J Mol Biol, vol. 361, no. 5, pp. 983–992, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Auton M, Bolen D, and Rösgen J, “Structural thermodynamics of protein preferential solvation: osmolyte solvation of proteins, amino acids, and peptides.,” Proteins, vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 802–813, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lim W, Rösgen J, and Englander S, “Urea, but not guanidinium, destabilizes proteins by forming hydrogen bonds to the peptide group.,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 106, no. 8, pp. 2595–2600, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Holthauzen L, Rösgen J, and Bolen D, “Hydrogen bonding progressively strengthens upon transfer of the protein urea-denatured state to water and protecting osmolytes.,” Biochemistry, vol. 49, no. 6, pp. 1310–1318, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Solecka B, Weise C, Laffan M, and Kannicht C, “Site-specific analysis of von Willebrand factor o- glycosylation.,” J Thromb Haemost, vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 733–746, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Lynch C, Cawte A, Millar C, Rueda D, and Lane D, “A common mechanism by which type 2a von Willebrand disease mutations enhance adamts13 proteolysis revealed with a von Willebrand factor a2 domain fret construct.,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 11, p. e0188405, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Scott J, Montgomery R, and Retzinger G, “Dimeric ristocetin flocculates proteins, binds to platelets, and mediates von Willebrand factor-dependent agglutination of platelets.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 266, no. 13, pp. 8149–8155, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Flood V, Friedman K, Gill J, Morateck P, Wren J, Scott J, and Montgomery R, “Limitations of the ristocetin cofactor assay in measurement of von Willebrand factor function.,” J Thromb Haemost, vol. 7, no. 11, pp. 1832–1839, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Badirou I, Kurdi M, Legendre P, Rayes J, Bryckaert M, Casari C, Lenting P, Christophe O, and Denis C, “In vivo analysis of the role of o-glycosylations of von Willebrand factor.,” PLoS One, vol. 7, no. 5, p. e37508, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Hampshire D, “Von Willebrand factor variant database, a member of the “european association for haemophilia and allied disorders”,” 2014.

- [42].Canis K, McKinnon T, Nowak A, Panico M, Morris H, Laffan M, and Dell A, “The plasma von Willebrand factor o-glycome comprises a surprising variety of structures including ABH antigens and disialosyl motifs.,” J Thromb Haemost, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 137–145, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dunne E, Qi Q, Shaqfeh E, O’Sullivan J, Schoen I, Ricco A, O’Donnell J, and Kenny D, “Blood group alters platelet binding kinetics to von Willebrand factor and consequently platelet function.,” Blood, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Franchini M, Capra F, Targher G, Montagnana M, and Lippi G, “Relationship between abo blood group and von Willebrand factor levels: from biology to clinical implications.,” Thromb J, vol. 5, p. 14, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jenkins P and O’Donnell J, “Abo blood group determines plasma von Willebrand factor levels: a biologic function after all,” Transfusion, vol. 46, no. 10, pp. 1836–1844, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Franchini M and Lippi G, “The intriguing relationship between the abo blood group, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.,” BMC Med, vol. 13, p. 7, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Bowen D, “An influence of abo blood group on the rate of proteolysis of von Willebrand factor by adamts13.,” J Thromb Haemost, vol. 1, pp. 33–40, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Gallinaro L, Cattini M, Sztukowska M, Padrini R, Sartorello F, Pontara E, Bertomoro A, Daidone V, Pagnan A, and Casonato A, “A shorter von Willebrand factor survival in o blood group subjects explains how abo determinants influence plasma von Willebrand factor.,” Blood, vol. 111, no. 7, pp. 3540–3545, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].O’Donnell J, McKinnon T, Crawley J, Lane D, and Laffan M, “Bombay phenotype is associated with reduced plasma-vwf levels and an increased susceptibility to adamts13 proteolysis.,” Blood, vol. 106, no. 6, pp. 1988–1991, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Rastegarlari G, Pegon J, Casari C, Odouard S, Navarrete A, Saint-Lu N, van Vlijmen B, Legendre P, Christophe O, Denis C, and Lenting P, “Macrophage lrp1 contributes to the clearance of von Willebrand factor.,” Blood, vol. 119, no. 9, pp. 2126–2134, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Wohner N, Legendre P, Casari C, Christophe O, Lenting P, and Denis C, “Shear stress-independent binding of von Willebrand factor-type 2b mutants p.r1306q & p.v1316m to lrp1 explains their increased clearance.,” J Thromb Haemost, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 815–820, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Denis C and Lenting P, “Vwf clearance: it’s glycomplicated.,” Blood, vol. 131, no. 8, pp. 842–843, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ward S, O’Sullivan J, Drakeford C, Aguila S, Jondle C, Sharma J, Fallon P, Brophy T, Preston R, Smyth P, Sheils O, Chion A, and O’Donnell J, “A novel role for the macrophage galactose-type lectin receptor in mediating von Willebrand factor clearance.,” Blood, vol. 131, no. 8, pp. 911–916, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Fu H, Jiang Y, Yang D, Scheiflinger F, Wong W, and Springer T, “Flow-induced elongation of von Willebrand factor precedes tension-dependent activation.,” Nat Commun, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 324, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Sing C and Alexander-Katz A, “Elongational flow induces the unfolding of von Willebrand factor at physiological flow rates.,” Biophys J, vol. 98, no. 9, pp. L35–7, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Schneider S, Nuschele S, Wixforth A, Gorzelanny C, Alexander-Katz A, Netz R, and Schneider M, “Shear-induced unfolding triggers adhesion of von Willebrand factor fibers.,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 104, no. 19, pp. 7899–7903, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Madabhushi S, Zhang C, Kelkar A, Dayananda K, and Neelamegham S, “Platelet gpibα binding to von Willebrand factor under fluid shear:contributions of the d’ d3-domain, a1-domain flanking peptide and o-linked glycans.,” J Am Heart Assoc, vol. 3, no. 5, p. e001420, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Zhang C, Kelkar A, Nasirikenari M, Lau J, Sveinsson M, Sharma U, Pokharel S, and Neelamegham S, “The physical spacing between the von Willebrand factor d’d3 and a1 domains regulates platelet adhesion in vitro and in vivo.,” J Thromb Haemost, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 571–582, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Interlandi G, Yakovenko O, Tu A, Harris J, Le J, Chen J, López J, and Thomas W, “Specific electrostatic interactions between charged amino acid residues regulate binding of von Willebrand factor to blood platelets.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 292, no. 45, pp. 18608–18617, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Lenting P, Christophe O, and Denis C, “von Willebrand factor biosynthesis, secretion, and clearance: connecting the far ends.,” Blood, vol. 125, no. 13, pp. 2019–2028, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Campbell J, Tischer A, Machha V, Moon-Tasson L, Sankaran B, Kim C, and Auton M, “Data on the purification and crystallization of the loss-of-function von Willebrand disease variant (p.gly1324ser) of the von Willebrand factor a1 domain.,” Data Brief, vol. 7, pp. 1700–1706, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Auton M, Cruz M, and Moake J, “Conformational stability and domain unfolding of the von Willebrand factor a domains.,” J Mol Biol, vol. 366, no. 3, pp. 986–1000, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Tischer A, Machha V, Rösgen J, and Auton M, ““cooperative collapse” of the denatured state revealed through Clausius-Clapeyron analysis of protein denaturation phase diagrams.,” Biopolymers, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Mayne L, Kan Z, Chetty P, Ricciuti A, Walters B, and Englander S, “Many overlapping peptides for protein hydrogen exchange experiments by the fragment separation-mass spectrometry method.,” J Am Soc Mass Spectrom, vol. 22, no. 11, pp. 1898–1905, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kan Z, Ye X, Skinner J, Mayne L, and Englander S, “Exms2: An integrated solution for hydrogen- deuterium exchange mass spectrometry data analysis.,” Anal Chem, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kan Z, Mayne L, Chetty P, and Englander S, “Exms: data analysis for hx-ms experiments.,” J Am Soc Mass Spectrom, vol. 22, no. 11, pp. 1906–1915, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Kan Z, Walters B, Mayne L, and Englander S, “Protein hydrogen exchange at residue resolution by proteolytic fragmentation mass spectrometry analysis.,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 110, no. 41, pp. 16438–16443, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Emsley J, Cruz M, Handin R, and Liddington R, “Crystal structure of the von Willebrand factor a1 domain and implications for the binding of platelet glycoprotein ib.,” J Biol Chem, vol. 273, no. 17, pp. 10396–10401, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Pettersen E, Goddard T, Huang C, Couch G, Greenblatt D, Meng E, and Ferrin T, “Ucsf chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis.,” J Comput Chem, vol. 25, no. 13, pp. 1605–1612, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.