Abstract

Relapse of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) remains a clinical challenge. We studied in a phase II trial whether the addition of peri-transplant rituximab would reduce the relapse risk compared to historical controls (n=157). Patients (n=55) received fludarabine and low-dose total body irradiation combined with rituximab on days −3, +10, +24, +36. Relapse rate at 3 years was significantly lower among rituximab-treated patients versus controls (17% vs. 31%; P=0.04). Overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS) and non-relapse mortality (NRM) were statistically similar: (53% vs. 50%; P=0.8), (44% vs. 42%; P=0.63), and (38% vs. 28%; P=0.2), respectively. In multivariate analysis, rituximab-treatment was associated with lower relapse rates both in the overall cohort [hazard ratio (HR): 0.34, P=0.006] and in patients with high-risk cytogenetics (HR: 0.21, P=0.0003). Patients with no comorbidities who received rituximab-conditioning had an OS rate of 100% and 75% at 1 and 3 years, respectively, with no NRM. Peri-transplant rituximab reduced relapse rates regardless of high-risk cytogenetics. HCT is associated with minimal NRM in patients without comorbidities and is a viable option for patients with high-risk CLL. Clinical trial information: .

INTRODUCTION

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) remains the only potentially curative treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), but it is complicated by non-relapse mortality (NRM) [1]. In recent years, novel agents like B-cell receptor inhibitors (ibrutinib, idelalisib and duvelisib) and a BCL-2 antagonist (venetoclax) have extended survivals for CLL patients in general and in particular for those with high-risk features for whom conventional chemo-immunotherapy regimens are not effective [2–4]. As a result, a decreasing number of CLL patients is offered HCT nationwide per the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) [5]. Despite the promising results from the novel agents, their efficacy is limited in high-risk CLL patients and sequential therapy is often required for these patients [6–10]. In addition, most of the current agents require an indefinite duration of treatment that can increase the cost and carries the risk of poor drug adherence [11, 12]. Therefore, and while newer agents and combinations are being studied, exclusive use of novel agents as the only therapeutic strategy in high-risk CLL patients seems to be premature and incorporation of HCT in selected patients with a reasonable risk/benefit ratio is still part of the standard approach to high-risk CLL patients [13–16]. In the meantime, interventions to improve the efficacy of allogeneic HCT for CLL are required.

CLL predominantly affects the elderly [17], Patients are referred to allogeneic HCT only after they have become unresponsive to other therapies, which usually occurs many years after diagnosis. Given their age and frequent comorbidities, patients with CLL are generally conditioned for HCT with reduced intensity regimens in order to minimize associated toxicities. Therefore, eradication of CLL cells relies largely on graft-versus-leukemia (GVL) effects. While GVL effects begin immediately after HCT, they are initially attenuated both by the need of the donor immune system to establish itself and by the broad immunosuppression from drugs given to control graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Given the reliance on GVL effects and their initial impairment, relapse of CLL has been the most pressing problem after allogeneic HCT, especially in patients with bulky disease or unfavorable-risk cytogenetics. This has affected long-term outcomes after HCT. Clinical efficacy and safety of anti-CD20 therapy for CLL in the pre-HCT setting has been shown where high-quality remissions were reported [18, 19]. In order to reduce the relapse risk, we evaluated the use of peri-transplant rituximab in a phase II trial. The trial was based on the hypothesis that rituximab could enhance early direct cell kill through antibody-dependent cytotoxicity [16]. Moreover, by inducing apoptosis, rituximab can promote uptake and cross-presentation of cell-derived peptides by antigen-presenting dendritic cells, resulting in a cross-priming and generation of donor-derived cytotoxic cells that might result in an earlier switch-on of GVL effects [20–22]. Safety and efficacy of a rituximab-based regimen using a different conditioning backbone had been shown in the clinical setting [20]. Here, we compare the results of the phase II trial to historical patients not given rituximab. The initial report of the historical experience has been previously published, and the outcomes have been updated for the purpose of this analysis.[23]

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Between 2009 and 2014, 55 CLL patients were given HCT after conditioning with a rituximab-based conditioning regimen. Of these patients, 50 were diagnosed with CLL and were treated on a single-arm phase II clinical trial for CLL (NCT00104858), and the other five were diagnosed with small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) and were treated on a separate phase-II study focused on lymphoma patients (NCT00867529). Both cohorts are collectively included in this analysis (rituximab cohort). We compared the outcome of the 55 patients with that of 157 patients who were transplanted at our institutions between 1997 and 2014 and did not receive rituximab (historical control) [17]. Protocols were approved by the institutional review boards of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the collaborating sites. All patients signed consent forms.

Phase-2 Trial Patients (Rituximab Cohort)

Patients with a diagnosis of CLL and SLL were included if they: 1) failed to achieve at least partial response (PR) after at 2 cycles of treatment with a fludarabine containing regimen (or another nucleoside analog); 2) experienced relapse within 12 months after completing a fludarabine containing regimen; 3) failed FCR (fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab) regimen at any time; or 4) had a deletion on the short arm of chromosome 17 (del17p) and were treated with at least one line of treatment. Patients with active infections, CNS involvement, or significant limitations in organ functions were excluded.

Donors

Both HLA-matched related and unrelated donors were allowed. All donors were HLA-matched at the allele level at HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1. For unrelated donors, a single allele disparity was allowed for HLA-A, -B, or -C as defined by high resolution typing. Only G-CSF mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were used as a hematopoietic cell source.

Study design and treatment

In the single-arm phase II study, transplants were performed in the outpatient setting, and patients were only admitted to inpatient services if medically indicated for the control of complications or for the infusion of donor PBMC if overnight infusion was logistically required. Conditioning began four days before HCT. From days –4 to –2, patients received fludarabine (30 mg/m2/day i.v.). On day 0, 200 cGy of total body irradiation (TBI) was administered at 6–10 cGy/min from a linear accelerator. PBMC were infused as soon as possible following TBI. Patients received rituximab at a dose of 375 mg/m2 on day −3 before and days +10, +24, and +38 after HCT. GVHD prophylaxis included cyclosporine (CSP) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF). CSP was started on day −3 at 5.0 mg/kg orally every 12 hours. In the absence of acute GVHD, CSP was continued until day +56 for related and until day +100 for unrelated recipients followed by taper to day +180. The CSP trough levels were kept at 400 ng/ml until day 28 and 120–360 ng/ml after day 28. MMF was started within 4–6 hours HCT at a dose of 15 mg/kg orally. In patients with related donors, MMF was stopped abruptly on day +27, while for unrelated recipients it was tapered from day +40 until day +96.

Historical controls

For historical comparison, we included data from all patients who underwent HCT for CLL or SLL on previous prospective and registered trials between 1997 and 2014 [17]. The conditioning regimen consisted of fludarabine 30 mg/m2/d days −4 to −2 followed by TBI (200 or 300 cGy) on day 0. GVHD prophylaxis consisted of a calcineurin inhibitor in addition to MMF as described above. These patients will be referred to as historical cohort.

Statistical analysis

The phase II study was designed to enroll 80 patients, in order to provide 89% power to detect improvement in an assumed historical 18-month overall survival rate of 45%, assuming a true survival rate of 60% and 1-sided 0.10 significance level. Enrollment to the study was terminated after 55 patients, due to slow accrual. In fact, 18-month overall survival exceeded 60% for both protocol patients and the historical control group described above. The statistical comparison used all available patients and was not based on specific power considerations.

Cumulative incidences of relapse and NRM and Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were calculated at 3 years for the rituximab cohort and historical cohort separately. This cut-off was chosen because of the shorter follow-up for the rituximab cohort. Associations between clinically relevant factors and clinical outcomes were assessed using univariate and multivariate cox proportional hazard models. All patients from both the rituximab and the historical cohorts were included and contributed to the model (n=215). Factors associated with at least one endpoint at the level of significance of 0.05 from the univariate models were included in the multivariate analysis. These models tested the following factors: age, donor type, CD34+ and CD3+ doses, disease status, diagnosis to transplant interval, numbers of prior treatments, HCT comorbidity index (HCT-CI), presence of bulky lymph nodes (> 5cm), fludarabine refractory disease, peri-transplant rituximab and high-risk cytogenetics. High-risk cytogenetics were defined as the presence of either del17p (detected by either analysis of G-banded chromosomes or by fluorescent in site hybridization ) or a complex karyotype (defined as 3 or more abnormalities in metaphase karyotype) at any time from diagnosis to transplant. Multivariable models were done separately for patients with high-risk cytogenetics. Response criteria was based on NCI-working group and the international workshop joint formal criteria for evaluating disease response for CLL [24, 25]. Progressive disease was defined as new lymphadenopathy or ≥ 50% increase in size of nodes, spleen, liver or circulating lymphocytes. Relapse was defined as meeting criteria of progression occurring 6 months after achievement of complete or partial remission.

All cited p-values associated with time-to-event comparisons are derived from hazard ratio analysis and do not refer to specific time points. All p-values are 2-sided and are unadjusted for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS v.8.0.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Pre-transplant characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Rituximab-treated patients and historical patients had the following statistically significant differences at baseline: The rituximab cohort more frequently had del17p (54% versus 18%, P<0.001) or complex cytogenetics (37% versus 18%, P=0.004) and more frequently received grafts from unrelated donors (69% versus 48%, P=0.008). Additionally, there was a suggestion that they had higher incidences of bulky lymph nodes (26% versus 14%, P=0.07) and of HCT-CI scores of ≥3 (47% versus 34%, P=0.08), respectively. Fifty-one patients (93%) from the rituximab-treated group were previously treated with a purine analog and 38 (69%) had FCR. All these patients were previously treated with rituximab at some point before allo-HCT. Focusing on the immediate treatment before transplant, rituximab-treated patients received CLL-directed therapy at median 283 days (range 26–539) before allo-HCT. For 50 of 55 pts (91%), treatment included an anti-CD20 antibody: FCR (n=10), bendamustine and rituximab (n=12), oxaliplatin, fludarabine, ara-C, and rituximab (n=8), single-agent ofatumumab (n=7), high-dose methylprednisone (HDMP) (n=4), single-agent rituximab (n=4), ofatumumab and HDMP (n=1), bendamustine and ofatumumab (n=1), and other rituximab-based chemo-immunotherapy regimens (n=3). Other patients received alemtuzumab (n=3), HDMP (n=1), and clofarabine (n=1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Rituximab (n=55) | Historical cohort (n=157) | P-value | All patients (n=212) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender, n (%) | 39 (71) | 119 (76) | 0.47 | 158 (75) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Caucasian | 53 (100) | 148 (95) | 201 (97) | |

| Others | 7 (5) | 0.12 | 7 (3) | |

| Age, Median (range) years | 59 (35–74) | 57 (38–72) | 0.06 | 58 (35–74) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| CLL | 53 (96) | 140 (89) | 193 (91) | |

| SLL | 1 (2) | 10 (6) | 11 (5) | |

| PLL | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | |

| Richter’s syndrome | 5 (3) | 0.30 | 5 (2) | |

| Years from diagnosis to HCT; median (range) | 5.8 (0.3–21.4) | 4.9 (0.4–26.9) | 0.21 | 5.0 (0.3–26.9) |

| Number of prior treatments; median (range) | 4 (1–10) | 4 (0–12) | 0.92 | 4 (0–12) |

| ≥ 5 prior treatments, n (%) | 19 (35) | 51 (33) | 0.80 | 70 (33) |

| Disease status at transplant, n (%) | ||||

| Complete Remission | 5 (10) | 10 (6) | 15 (7) | |

| Partial Remission | 10 (20) | 56 (36) | 66 (32) | |

| Unresponsive | 30 (59) | 75 (49) | 105 (51) | |

| Untreated Relapse | 6 (12) | 13 (8) | 0.14 | 19 (9) |

| Cytogenetics, n (% of tested patients) | ||||

| del (17p) | 29 (54) | 26 (18) | <0.0001 | 55 (27) |

| del (11q) | 11 (20) | 28 (19) | 0.82 | 39 (19) |

| trisomy 12 | 6 (11) | 23 (16) | 0.43 | 29 (14) |

| del (13q) | 18 (33) | 61 (41) | 0.31 | 79 (39) |

| complex | 20 (37) | 26 (18) | 0.004 | 46 (23) |

| Donor Type, n (%) | ||||

| Related | 17 (31) | 81 (52) | 98 (46) | |

| Unrelated | 38 (69) | 76 (48) | 0.008 | 114 (54) |

| HCT-CI | ||||

| Median (range) | 2 (0–6) | 2 (0–9) | 0.006 | 2 (0–9) |

| HCT-CI ≥ 3, n (%) | 26 (47) | 51 (34) | 0.08 | 77 (38) |

| Conditioning Regimen, n (%) | ||||

| Fludarabine, TBI 2Gy | 52 (95) | 128 (82) | 180 (85) | |

| Fludarabine, TBI 3Gy | 3 (5) | 7 (4) | 10 (5) | |

| TBI 2Gy | 0 | 22 (14) | 0.01 | 22 (10) |

| Cell transplanted, Median (range) | ||||

| CD34+ × 106/kg | 7.8 (1.5–28.4) | 8.1 (1.1–37.8) | 0.79 | 8.0 (1.1–37.8) |

| CD3+ × 106/kg | 2.9 (0.0–42.3) | 2.9 (0.0–6.7) | 0.77 | 2.9 (0.0–42.3) |

| Fludarabine-refractory disease, n (%) | 18 (33) | 48 (31) | 0.77 | 66 (31) |

| Lymph node size ≥ 5 cm, n (%) | 14 (26) | 20 (14) | 0.07 | 34 (18) |

Outcomes

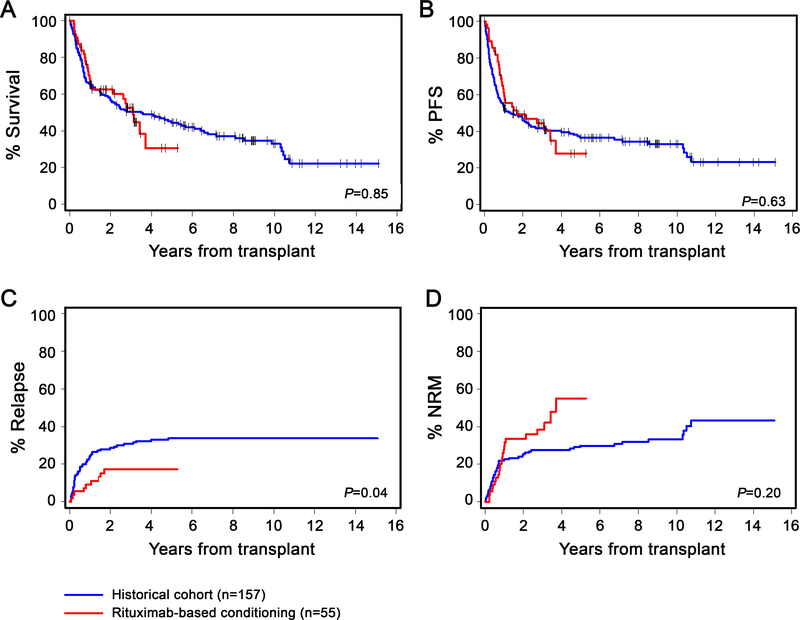

The median duration of follow-up for rituximab-treated, historical, and all patients was 35 months (range: 7–63), 86 months (range: 3–181) and 60 months (range: 3–181), respectively. Rituximab-treated patients had a comparable complete remission (CR) rate of 44% compared to 48% among historical patients (p=0.59). However, the rate of relapse at 3 years was statistically significantly lower among the rituximab cohort than historical patients (17% [95% CI, 7–27%] versus 31% [95% CI, 23–38%], p=0.04). There were no statistically significant differences in the unadjusted rates of OS (53% [95% CI, 38–67%] versus 50% [95% CI, 42–58%], p=0.85), PFS (44% [95% CI, 31–58%] versus 42% [95% CI, 34–50%], p=0.63), or NRM (38% [95% CI, 25–52%] vs. 28% [95% CI, 20–35%]; p=0.20) between the two groups of patients. (Figures 1A–D).

Figure-1: Kaplan–Meier curves for (A) overall survival, (B) progression-free survival, (C) relapse, and (D) non-relapse mortality.

comparing patients who were treated with rituximab-based conditioning on the phase-II clinical trial (red) and historical cohort patients (blue). P-values are by log-rank test.

Given the strong association between the HCT-CI and the clinical outcomes, we separately analyzed the outcomes among patients without comorbidities (HCT-CI = 0; n=55). The 1-year and 3-year OS rates were 100% and 75% [95% CI, 33–100%] among rituximab-treated patients (n=8) versus 77 % [95% CI, 64–89%] and 63% [95% CI, 49–77%], respectively, among the historical patients (n=47). NRM rates were 0% and 13% [95% CI, 3–23%] for rituximab-treated and historical patients with no comorbidities, respectively.

Toxicities

Severe neutropenia (<500 cells/μL) was more common in the rituximab cohort (15.1% vs. 10.4%; P=0.01), but incidence of severe thrombocytopenia (< 20,000 cells/μL) was similar between the two groups (0.5% vs. 2.5; P=0.49). There was also no difference in rate of colony-stimulating growth factor use (4.9% vs. 3.0%; P =0.20), blood (RBC) transfusion (6.3% vs. 6.3%; P=0.97) or platelet transfusion (2.5% vs. 5.1%; P=0.06) between the rituximab and historical cohorts. Non-hematologic adverse events (AEs) were similar between the two cohorts, with hyperbilirubinemia (13% vs. 13%; p =0.9), hypoxia (9% vs. 11%; p =0.71), and elevated creatinine (9% vs. 5%; p=0.28) as the most common AEs. Table-2 summarizes details of non-hematologic events in the two groups of patients.

Table 2.

Patients with grade 3–4 adverse events*

| Event | Rituximab (total n=55), n (%) | Historical cohort (total n=157), n (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatic | |||

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 7 (13) | 21 (13) | 0.9 |

| Renal | |||

| Elevated creatinine | 5 (9) | 8 (5) | 0.28 |

| Tumor lysis syndrome | 0 | 3 (2) | 0.30 |

| Cardiovascular | |||

| Hypertension | 3 (5.5) | 1 (0.5) | 0.02 |

| Hypotension | 2 (3.5) | 6 (4) | 0.95 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (2) | 3 (2) | 0.96 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.76 |

| Cardiopulmonary arrest | 1 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.43 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0 | 3 (2) | 0.30 |

| Acute Coronary Syndrome | 0 | 3 (2) | 0.30 |

| Infectious | |||

| Hepatitis C | 1 (2) | 0 | 0.09 |

| Encephalitis | 1 (2) | 0 | 0.09 |

| Pneumonia | 1 (2) | 0 | 0.09 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 1 (2) | 6 (4) | 0.47 |

| SEPSIS/septic shock | 0 | 5 (3) | 0.18 |

| Disseminated/invasive fungal infection | 0 | 4 (2.5) | 0.23 |

| Pulmonary | |||

| Pleural effusion | 1 (2) | 4 (2.5) | 0.75 |

| Dyspnea | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.76 |

| Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage | 1 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.43 |

| Hypoxia | 5 (9) | 17 (11) | 0.71 |

| Gastrointestinal† | |||

| Diarrhea | 1 (2) | 2 (1) | 0.76 |

| Bleeding | 2 (3.5) | 2 (1) | 0.26 |

| Anorexia | 1 (2) | 0 | 0.09 |

| Colitis | 0 | 5 (3) | 0.18 |

| Nausea and vomiting | 1 (2) | 3 (2) | 0.96 |

| Neurological | |||

| Neuropathy | 1 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.43 |

| Insomnia | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 0.55 |

| Depression | 1 (2) | 0 | 0.09 |

| Seizure | 1 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.43 |

| Syncope | 0 | 3 (2) | 0.30 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 1 (2) | 0 | 0.09 |

Occurring in ≥ 1% of patients

Unrelated to GVHD

GVHD

The incidences of grade 2–4 acute GVHD (69% vs. 58%; P=0.53) and grade 3–4 acute GVHD (18% vs. 18%; P=0.98) were not statistically significantly different between rituximab and historical patients. There was also no difference in the incidence of chronic GVHD at 3 years between the two groups (66% vs. 55%; P=0.68).

Causes of death

Fifty percent of the rituximab patients died. Causes of death included infections (18%), acute GVHD complications (12%), disease relapse or progression (10%), complications of chronic GVHD (6%), and other causes (4%). Among the historical patients, 62.5% died. Causes of death included disease relapse or progression (27%), infections (13%), and complications from acute (6%) or chronic (3%) GVHD. Other deaths were from neurologic events (2.5%), secondary malignancies (2.5%), or other causes (8%). The cause of death was unknown in one patients.

Predictors of clinical outcomes

In order to identify independent prognostic factors for clinical outcomes, we developed univariate and multivariate models using data from the entire cohort of patients (n=212). In the multivariable models (Table 3), peri-transplant rituximab (HR 0.34, P=0.006) and unrelated grafts (HR 0.37, P=0.0007) were significantly associated with a lower relapse rate, while high-risk cytogenetics increased the risk of relapse (HR: 4.61, P<0.0001). HCT-CI scores of ≥3 were the only predictor for increased NRM (HR 3.63, P=0.001). None of these factors significantly predicted OS with the exception for a suggestive association with HCT-CI scores of ≥3 (HR: 1.62, p=0.06). Unrelated grafts predicted improved PFS (HR: 0.69, P=0.05), while high-risk cytogenetics predicted worse PFS (HR: 1.84, P=0.004).

Table 3.

Multivariable model of association between relevant clinical factors and outcomes in all patients*

| Overall Mortality (114 events) |

PFS (121 events) |

Relapse (55 events) |

NRM (66 events) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p- value | HR (95% CI) | p- value | HR (95% CI) | p- value | HR (95% CI) | p- value | |

| Donor | ||||||||

| Related | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Unrelated | 0.87 (0.6–1.3) | 0.49 | 0.69 (0.5–1.0) | 0.05 | 0.37 (0.2–0.7) | 0.0007 | 1.13 (0.7–1.9) | 0.66 |

| HCT-CI | ||||||||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 1–2 | 1.21 (0.7–2.0) | 0.45 | 1.28 (0.8–2.1) | 0.32 | 0.78 (0.4–1.5) | 0. 46 | 2.24 (1.0–5.1) | 0.05 |

| 3+ | 1.62 (1.0–2.6) | 0.06 | 1.52 (0.9–2.5) | 0.09 | 0.59 (0.3–1.2) | 0.13 | 3.63 (1.6–8.0) | 0.001 |

| High risk CG ** | ||||||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Yes | 1.40 (0.9–2.1) | 0.13 | 1.84 (1.2–2.8) | 0.004 | 4.61 (2.5–8.6) | <0.0001 | 0.89 (0.5–1.6) | 0.68 |

| Rituximab | ||||||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Yes | 0.94 (0.6–1.5) | 0.81 | 0.78 (0.5–1.2) | 0.27 | 0.34 (0.2–0.7) | 0.006 | 1.42 (0.8–2.5) | 0.23 |

Following factors were included in the univariate models and only moved to the multivariable model if reached statistical significance (p <0.05) for any endpoint in the univariate models: age, donor type, disease status, CD34+ and CD3+ doses, number of prior treatments, diagnosis to transplant interval, high risk CG, HCT comorbidity index (HCT-CI), presence of bulky lymph nodes (> 5cm), fludarabine refractory disease and rituximab-containing conditioning

del 17p or complex CG (defined as 3 or more abnormalities)

We looked specifically for prognostic markers in patients with high-risk cytogenetics as they are more likely to be offered HCT in the era of novel agents. Among those patients (Table 4), having an unrelated donor was associated with both better PFS (HR: 0.38, P=0.003) and lower relapse (HR: 0.21, P=0.0003). Peri-transplant rituximab was associated with a lower relapse rate (HR: 0.42, P=0.04). Higher HCT-CI was associated with higher NRM.

Table 4.

Multivariable model of association between relevant clinical factors and outcomes in patients with high-risk CG (del 17p or complex) *

| Overall Mortality (42 events) | PFS (49 events) |

Relapse (27 events) |

NRM (22 events) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p- value | HR (95% CI) | p- value | HR (95% CI) | p- value | HR (95% CI) | p- value | |

| Donor | ||||||||

| Related | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Unrelated | 0.63 (0.3–1.2) | 0.18 | 0.38 (0.2–0.7) | 0.003 | 0.21 (0.1–0.5) | 0.0003 | 0.84 (0.3–2.4) | 0.74 |

| CD34 dose/kg | ||||||||

| <7.80 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| ≥7.80 | 1.59 (0.8–3.0) | 0.16 | 1.63 (0.9–2.9) | 0.10 | 1.12 (0.5–2.5) | 0.79 | 2.47(1.0–6.4) | 0.06 |

| Number of regimens | ||||||||

| 0–4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 5+ | 1.39 (0.7–2.7) | 0.33 | 1.30 (0.7–2.4) | 0.41 | 1.26 (0.5–2.9) | 0.59 | 1.20 (0.5–3.0) | 0.70 |

| HCT-CI | ||||||||

| 0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| 1–2 | 0.96 (0.4–2.3) | 0.93 | 0.76 (0.3–1.7) | 0.51 | 0.27 (0.1–0.8) | 0.01 | * | 0.005 |

| 3+ | 0.88 (0.4–2.0) | 0.75 | 0.72 (0.3–1.5) | 0.38 | 0.31 (0.1–0.8) | 0.01 | * | 0.009 |

| Rituximab | ||||||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| Yes | 0.94 (0.5–1.8) | 0.86 | 0.80 (0.4–1.4) | 0.46 | 0.42 (0.2–1.0) | 0.04 | 1.64 (0.6–4.2) | 0.31 |

Following factors were included in the univariate models and only moved to the multivariable model if reached statistical significance (p <0.05) in the univariate models: age, donor type, disease status, CD34+ and CD3+ doses, number of prior treatments, diagnosis to transplant interval, HCT comorbidity index (HCT-CI), presence of bulky lymph nodes (> 5cm), fludarabine refractory disease and rituximab-containing conditioning

HR not estimable due to 0 events in reference category.

DISCUSSION

CLL patients with high-risk cytogenetics continue to have relatively poor outcomes with elusive chances of cure. In this phase II study, we showed that the addition of 4 doses of peri-transplant rituximab to our traditional minimal-intensity conditioning regimen before HCT resulted in a 3-fold decrease in relapse rates. This benefit was also present among patients with high-risk cytogenetics. Our study confirms previous reports by us and others indicating high long-term PFS and OS rates in patients with high-risk CLL after HCT [1, 23, 26–28]. Likewise, unrelated grafts achieved better disease control, supporting the use of such grafts to treat high-risk CLL. In addition, CLL patients with no comorbidities experienced a 3-fold lower incidence of NRM compared to those with multiple comorbidities. While patient numbers were relatively small, 75% of those CLL patients without comorbidities given rituximab-based conditioning regimen were disease free at 3-years. This suggests that HCT should strongly be considered as treatment of choice for high-risk CLL patients without comorbidities. Recent clinical practice guidelines by the American Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (ASBMT), the International Workshop on CLL (iwCLL), and the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) and European Research Initiative on CLL (ERIC) recommend allogeneic HCT for high-risk CLL patients with refractory disease while they are still responding to either BCR inhibitors or venetoclax [13–16]. Our finding supports that recommendation from the safety standpoint, especially for patients with no comorbidity.

Addition of rituximab was feasible, improved clinical efficacy, and was independently associated with a lower relapse rate both in the entire cohort and in patients with high-risk cytogenetics. More than half of the patients were alive at 3 years, and more than 40% were alive without disease progression. Rituximab-treated patients had more comorbidities than historical patients, which might explain their slightly higher NRM and comparable OS despite the lower relapse rate seen with rituximab. Khoury et al. reported excellent 2-year OS and PFS (90% and 75%, respectively) with rituximab-containing conditioning regimen [29]. Also, Montesinos et al. also observed a lower relapse rate but higher NRM when they added ofatumumab to the conditioning regimen [30]. Our findings are in line with recent reports indicating an independent association between high-risk cytogenetics (del17p or complex karypote) and a higher relapse rate and shorter PFS, although we did not find an association with OS confirming the findings from the German group [26, 27]. It should be noted that given the shorter follow-up for rituximab-treated patients, true estimate of relapse -especially late ones- may be different with longer follow-up. Also, rituximab cohort were transplanted in more recent years, and these patients have potentially benefited from improved post-HCT care in this era.

We believe that HCT remains a viable treatment option for CLL in the era of novel agents. Despite the introduction of new drugs, CLL remains incurable, and the duration of response to the novel agents is limited. Ibrutinib – the most effective drug for high-risk CLL to date – provides a median PFS duration of 26 months in patients with del17p based on the longest published follow-up in the relapsed setting [8] Similar PFS (27 months) has recently been reported in CLL patients with del17p who were treated with venetoclax in the relapsed setting [9, 31]. While these results are significantly better than the historical treatments [32], they also indicate that cure of high-risk CLL using non-transplant approaches remains an unmet need. Also, drug tolerability remains an issue in a number of patients and has resulted in treatment discontinuation in 30–40% of patients taking ibrutinib or venetoclax based on the “real-world” data [12, 33].

Immunotherapy using chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR-T) is another novel approach that has shown promising results in extremely high-risk CLL patients. Admittedly, the follow-up for this experimental treatment is still very limited, hampering head-to-head comparisons with allogeneic HCT or even with novel agents. Further, long-term remissions were only observed in patients in a fraction of patients who achieved deep molecular responses [34]. In the future, CLL investigators could be interested in comparing these two immunologically-based treatment approaches (CAR-T versus nonmyeloablative allogeneic HCT) in a randomized clinical trial and/or explore the approach of using CAR-T as a debulking treatment before allogeneic HCT to enhance long-term remissions particularly in high-risk CLL. Our current institutional approach to high-risk CLL patients is mainly in line with EBMT/ERIC guidelines [16] and involves using novel therapeutic agents in the first- and second-line settings. Patients who show disease progression after first novel agent (usually a BTKi or venetoclax), will be counselled about cellular therapy and depending on availability of CAR-T option (currently only available on a clinical trial), donor status and medical comorbidities, CAR-T or allo-HCT is recommended. With this approach, majority of patients receive CAR-T before allo-HCT. In patients with detectable disease after CAR-T, allo-HCT remains the most important treatment modality.

Despite robust efficacy data for HCT, the higher incidence of NRM compared to non-transplant approaches is the main clinical concern. It is therefore critically important to investigate novel strategies to reduce NRM after HCT. In this context, very encouraging data on statistically significant reductions in both serious acute GVHD and NRM among unrelated HCT recipients have recently been reported using triple GVHD prevention with MMF, CSP, and sirolimus [35]. In addition, and as alternative treatments for high-risk CLL become more effective and safer, it is important to identify patients with a low comorbidity burden for whom an earlier utilization of HCT with the intent of cure should be considered.

Our study has number of limitations. First, the treatment landscape of CLL has changed dramatically and we acknowledge that in the current era, transplant outcomes can be affected by pre or post HCT use of novel agents (BTKi, venetoclax or PI3 Kinase inhibitors). Second, given the likelihood of later relapse in CLL patients, longer follow-up of our rituximab-treatment patient in necessary to provide more accurate estimate of disease control.

In conclusion, incorporation of rituximab to the conditioning regimen was feasible and effective. Our results encourage future utilization of newer anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies that have been shown to be superior to rituximab for CLL [36]. Our findings support early utilization of HCT for patients with high-risk CLL with no comorbidities to avoid clinical and financial toxicities of non-HCT therapies that do not necessarily promise cure. This approach has the potential to provide prolonged disease control with an acceptable risk of treatment-related mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Helen Crawford for her assistance with manuscript/figure preparations.

Funding Sources: Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number P01 CA078902, P01 CA018029, P30 CA015704, and by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under K99/R00 HL088021 (M.L.S.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, which had no involvement in the study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; nor in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

M. Shadman provided consultancy for Abbvie, Genentech, Astra Zeneca and Sound Biologics; has been on the advisory board for Abbvie, Genentech, Pharmacyclics, Astra Zeneca, ADC Therapeutics, Atara, and Verastem; and receives research funding from Mustang Biopharma, Pharmacyclics, Gilead, Genentech, TG Therapeutics, Bigene, Celgene, Acerta, Emergent, Sunesis and Merck. Otherwise, the authors have no other conflicts to declare.

REFERENCES

as of 17-Jul-2019

- 1.Brown JR, Kim HT, Armand P, Cutler C, Fisher DC, Ho V et al. Long-term follow-up of reduced-intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: prognostic model to predict outcome. Leukemia 2013; 27(2): 362–369. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byrd JC, Furman RR, Coutre SE, Burger JA, Blum KA, Coleman M et al. Three-year follow-up of treatment-naive and previously treated patients with CLL and SLL receiving single-agent ibrutinib. Blood 2015; 125(16): 2497–2506. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-606038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furman RR, Sharman JP, Coutre SE, Cheson BD, Pagel JM, Hillmen P et al. Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(11): 997–1007. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, Kahl BS, Puvvada SD, Gerecitano JF et al. Targeting BCL2 with Venetoclax in Relapsed Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2016; 374(4): 311–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Souza AZX. Current Uses and Outcomes of Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (HCT): CIBMTR Summary Slides, 2016. . In, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jain P, Keating M, Wierda W, Estrov Z, Ferrajoli A, Jain N et al. Outcomes of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia after discontinuing ibrutinib. Blood 2015; 125(13): 2062–2067. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-09-603670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maddocks KJ, Ruppert AS, Lozanski G, Heerema NA, Zhao W, Abruzzo L et al. Etiology of Ibrutinib Therapy Discontinuation and Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. JAMA Oncol 2015; 1(1): 80–87. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Brien S, Furman RR, Coutre S, Flinn IW, Burger JA, Blum K et al. Single-agent ibrutinib in treatment-naive and relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a 5-year experience. Blood 2018; 131(17): 1910–1919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-10-810044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venetoclax in relapsed/refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) with 17p deletion: outcome and minimal residual disease (MRD) from the full population of the pivotal M13–982 trial. Society of Hematology Oncology (SOHO), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones JA, Mato AR, Wierda WG, Davids MS, Choi M, Cheson BD et al. Venetoclax for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia progressing after ibrutinib: an interim analysis of a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19(1): 65–75. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30909-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Q, Jain N, Ayer T, Wierda WG, Flowers CR, O’Brien SM et al. Economic Burden of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia in the Era of Oral Targeted Therapies in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2017; 35(2): 166–174. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mato AR, Hill BT, Lamanna N, Barr PM, Ujjani CS, Brander DM et al. Optimal sequencing of ibrutinib, idelalisib, and venetoclax in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results from a multicenter study of 683 patients. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO 2017; 28(5): 1050–1056. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kharfan-Dabaja MA, Kumar A, Hamadani M, Stilgenbauer S, Ghia P, Anasetti C et al. Clinical Practice Recommendations for Use of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia on Behalf of the Guidelines Committee of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2016; 22(12): 2117–2125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Dohner H et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood 2018; 131(25): 2745–2760. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-09-806398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gribben JG. How and when I do allogeneic transplant in CLL. Blood 2018. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-01-785998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreger P, Ghia P, Schetelig J, van Gelder M, Kimby E, Michallet M et al. High-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia in the era of pathway inhibitors: integrating molecular and cellular therapies. Blood 2018; 132(9): 892–902. e-pub ahead of print 2018/07/13; doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-01-826008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, Jack A, Roman E. Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer 2011; 105(11): 1684–1692. e-pub ahead of print 2011/11/03; doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davids MS, Kim HT, Yu L, De Maeyer G, McDonough M, Vartanov AR et al. Ofatumumab plus high dose methylprednisolone followed by ofatumumab plus alemtuzumab to achieve maximal cytoreduction prior to allogeneic transplantation for 17p deleted or TP53 mutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia(). Leukemia & lymphoma 2019; 60(5): 1312–1315. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2018.1519814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schetelig J, Link CS, Stuhler G, Wagner EM, Hanel M, Kobbe G et al. Anti-CD20 immunotherapy as a bridge to tolerance, after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: results of the CLLX4 trial. British journal of haematology 2019; 184(5): 833–836. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khouri IF, Lee MS, Saliba RM, Andersson B, Anderlini P, Couriel D et al. Nonablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: impact of rituximab on immunomodulation and survival. Exp Hematol 2004; 32(1): 28–35. e-pub ahead of print 2004/01/17; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selenko N, Maidic O, Draxier S, Berer A, Jager U, Knapp W et al. CD20 antibody (C2B8)-induced apoptosis of lymphoma cells promotes phagocytosis by dendritic cells and cross-priming of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Leukemia 2001; 15(10): 1619–1626. e-pub ahead of print 2001/10/06; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selenko N, Majdic O, Jager U, Sillaber C, Stockl J, Knapp W. Cross-priming of cytotoxic T cells promoted by apoptosis-inducing tumor cell reactive antibodies? J Clin Immunol 2002; 22(3): 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sorror ML, Storer BE, Sandmaier BM, Maris M, Shizuru J, Maziarz R et al. Five-year follow-up of patients with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2008; 26(30): 4912–4920. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Grever M, Kay N, Keating MJ, O’Brien S et al. National Cancer Institute-sponsored Working Group guidelines for chronic lymphocytic leukemia: revised guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. Blood 1996; 87(12): 4990–4997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Dohner H et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood 2008; 111(12): 5446–5456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim HT, Hu Z-H, Woo Ahn K, Davids M, Volpe V, Alyea E et al. Prognostic Score and Cytogenetic Risk Classification for Chronic Lymphocyteic Leukemia Patients Who Underwent Reduced Intensity Conditioning Allogeneit HCT: A CIBMTR Report. Blood 2017; 130(Suppl 1): 667–667. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramer I, Stilgenbauer S, Dietrich S, Bottcher S, Zeis M, Stadler M et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for high-risk CLL: 10-year follow-up of the GCLLSG CLL3X trial. Blood 2017; 130(12): 1477–1480. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-775841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shea T, Johnson J, Westervelt P, Farag S, McCarty J, Bashey A et al. Reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation provides high event-free and overall survival in patients with advanced indolent B cell malignancies: CALGB 109901. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2011; 17(9): 1395–1403. e-pub ahead of print 2011/02/08; doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khouri IF, Wei W, Korbling M, Turturro F, Ahmed S, Alousi A et al. BFR (bendamustine, fludarabine, and rituximab) allogeneic conditioning for chronic lymphocytic leukemia/lymphoma: reduced myelosuppression and GVHD. Blood 2014; 124(14): 2306–2312. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-587519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montesinos P, Cabrero M, Valcarcel D, Rovira M, Garcia-Marco JA, Loscertales J et al. The addition of ofatumumab to the conditioning regimen does not improve the outcome of patients with high-risk CLL undergoing reduced intensity allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation: a pilot trial from the GETH and GELLC (CLL4 trial). Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51(10): 1404–1407. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stilgenbauer S, Eichhorst B, Schetelig J, Hillmen P, Seymour JF, Coutre S et al. Venetoclax for Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia With 17p Deletion: Results From the Full Population of a Phase II Pivotal Trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2018: JCO2017766840. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.6840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown JR, Porter DL, O’Brien SM. Novel treatments for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and moving forward. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book / ASCO. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Meeting 2014; 34: e317–325. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.e317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mato AR, Thompson M, Allan JN, Brander DM, Pagel JM, Ujjani CS et al. Real world outcomes and management strategies for venetoclax-treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients in the United States. Haematologica 2018. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.193615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turtle CJ, Hay KA, Hanafi LA, Li D, Cherian S, Chen X et al. Durable molecular remissions in chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated with CD19-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells after failure of ibrutinib. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(26): 3010–3020. e-pub ahead of print 2017/07/18; doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.8519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandmaier BM, Maloney DG, Storer BE, Olesen G, Maris MB, Gutman JA et al. Sirolimus combined with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and cyclosporine (CSP) significantly improves prevention of acute graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) after unrelated hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT): Results from a phase III randomized multi-center trial (Abstract). Blood 2016; 128(22): #506; http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/128/522/506. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goede V, Fischer K, Busch R, Engelke A, Eichhorst B, Wendtner CM et al. Obinutuzumab plus chlorambucil in patients with CLL and coexisting conditions. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(12): 1101–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]