Abstract

Background: Both medical weight management (MWM) and bariatric surgery are significantly underutilized by patients with severe obesity, particularly males. Less than 30% of participants in MWM programs are male, and only 20% of patients undergoing bariatric surgery are men.

Objectives: To identify motivations of males who pursue either MWM or bariatric surgery.

Setting: Interviews with males with severe obesity (body mass index ≥35 kg/m2), who participated in a Veteran Affairs weight loss program in the Midwest.

Materials and Methods: Participants were asked to describe their experiences with MWM and bariatric surgery. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and uploaded to NVivo for data management and analysis. Five coders iteratively developed a codebook using inductive content analysis to identify relevant themes. We utilized theme matrices organized by type of motivation and treatment pathway to generate higher-level analysis and generate themes.

Results: Twenty-five males participated. Participants were 58.7 (standard deviation 8.6) years old on average, and 24% were non-white. Motivations for pursuing MWM or surgery included a desire to improve physical or psychological health and to enhance quality of life. Patients seeking bariatric surgery were motivated by the fear of death and felt that they had exhausted all other weight loss options. MWM patients believed they had more time to pursue other weight loss options.

Conclusion: The opportunity to improve health, optimize quality of life, and lengthen lifespan motivates males with severe obesity to pursue weight loss treatments. These factors should be considered when providers educate patients about obesity treatment options and outcomes.

Keywords: bariatric surgery, weight loss, motivations, obesity, males

Introduction

Severe obesity (body mass index [BMI] of ≥35 kg/m2) is associated with numerous health conditions, including cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes.1 The main treatments for weight loss are medical weight management (MWM), including dietary and physical activity changes with or without weight management medication or bariatric surgery. Both MWM and bariatric surgery are significantly underutilized, particularly by men. One recent systematic review found that only 27% of participants in MWM programs were male.2 Only 15% of weight management medication users are males.3 Fewer than 1% of patients who meet BMI criteria for bariatric surgery undergo surgery; only 20% of those patients are male.4

Literature is lacking regarding the motivations of males with severe obesity, who pursue either MWM or bariatric surgery. Two mixed-gender studies discussed subanalyses of male motivations for MWM such as wanting to improve overall physical health and well-being, as well as the desire to have an ideal body image.5,6 Studies on male motivations for seeking bariatric surgery are limited by low numbers of male patients. Several mixed-gender studies reported subanalyses of male patients' motivations for pursuing bariatric surgery, including medical conditions and health concerns, weight stigma, and reduced work functioning.7–9

In this study, we analyzed 25 semistructured interviews with male Veterans with severe obesity, who participated in a Veteran Affairs (VA) weight loss program. We also identified and described patient motivations for pursuing either MWM or bariatric surgery.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This report is a secondary analysis of patient interviews that were conducted as part of a study investigating barriers and facilitators of severe obesity treatment within the VA. We conducted qualitative interviews with Veterans with severe obesity, who participated in a VA MWM program (MOVE!), which involves individual visits with patients or group classes on nutrition, exercise, and goal-setting.

We identified patients through an administrative data pull of electronic health records. We included Veterans from two VA Medical Centers in the Midwest, who met the following criteria for bariatric surgery: (1) BMI of 35.0–39.9 kg/m2 accompanied by an obesity-related comorbidity (coronary artery disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and obstructive sleep apnea and (2) BMI ≥40 kg/m2. We excluded Veterans older than 70. Patients who participated in VA MWM were eligible if they attended at least three MOVE! visits, with the first visit being 6–18 months before the initiation of the study. This allowed us to target patients who participated in the MOVE! program long enough that they could have been evaluated for bariatric surgery. The ICD-9 codes and MOVE! visit criterion are listed in Appendices 1 and 2, respectively.

Patients who pursued bariatric surgery were eligible if they were referred for bariatric surgery and/or underwent bariatric surgery, and attended at least one visit within MOVE! between January 1, 2011, and June 1, 2016 (Appendix 3). Extracting data from this longer time period allowed us to obtain an adequate sample size of patients who underwent bariatric surgery.

Data collection

Veterans were sent recruitment letters asking them to participate in a 60-minute semistructured interview. We obtained verbal consent for phone interviews and written consent for in-person interviews. Participants were asked to describe their experience with weight loss treatment options, their motivations for pursuing bariatric surgery or MWM, and their experience with treatment compared to their goals. Interview guides are shown in Appendix 4.

Data analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed. and uploaded to NVivo for data management and analysis.10 We analyzed the data using conventional content analysis, which included both emergent codes and a priori codes based on our research questions.11 Four members of the research team coded 10% of transcripts independently to develop the initial codebook. We used memos and annotations to facilitate our analysis. After initial coding, the group convened to discuss the codes and determine code definitions. This procedure was repeated for each subsequent transcript, using the technique of constant comparison to finalize our codebook.12 After finalizing the codebook, 3 coders (S.A.J., E.A., and G.S.) independently coded the remaining transcripts. We extracted the codes “motivations for surgery” and “motivations for weight loss” and utilized theme matrices tabulated by type of motivation and treatment (MWM or bariatric surgery) pathway to conduct higher-level analysis and generate themes.13

The study was approved by the UW-Madison Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the William S. Middleton VA Research & Development Committee (VA R&D).

Results

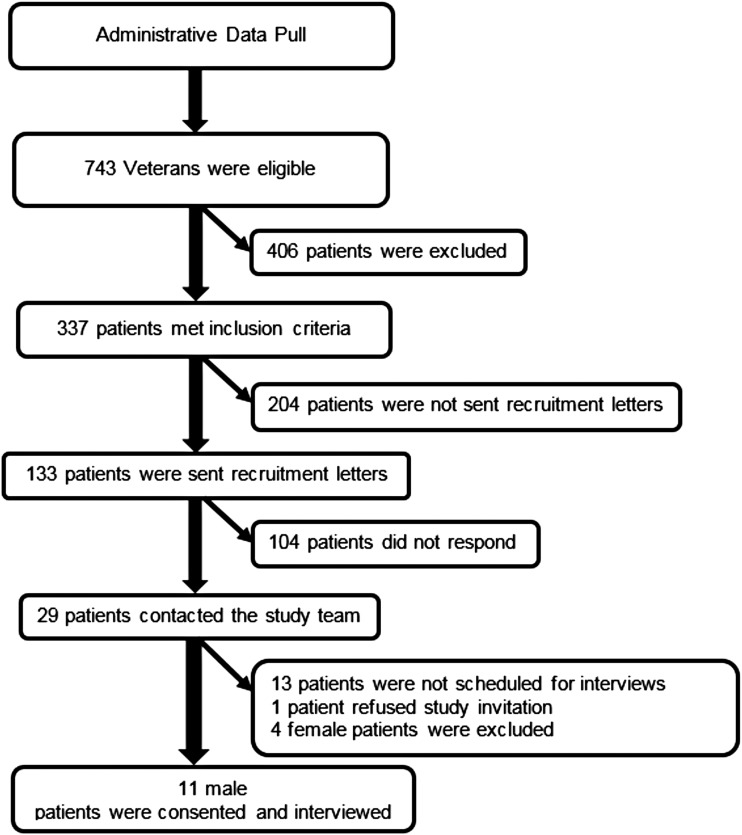

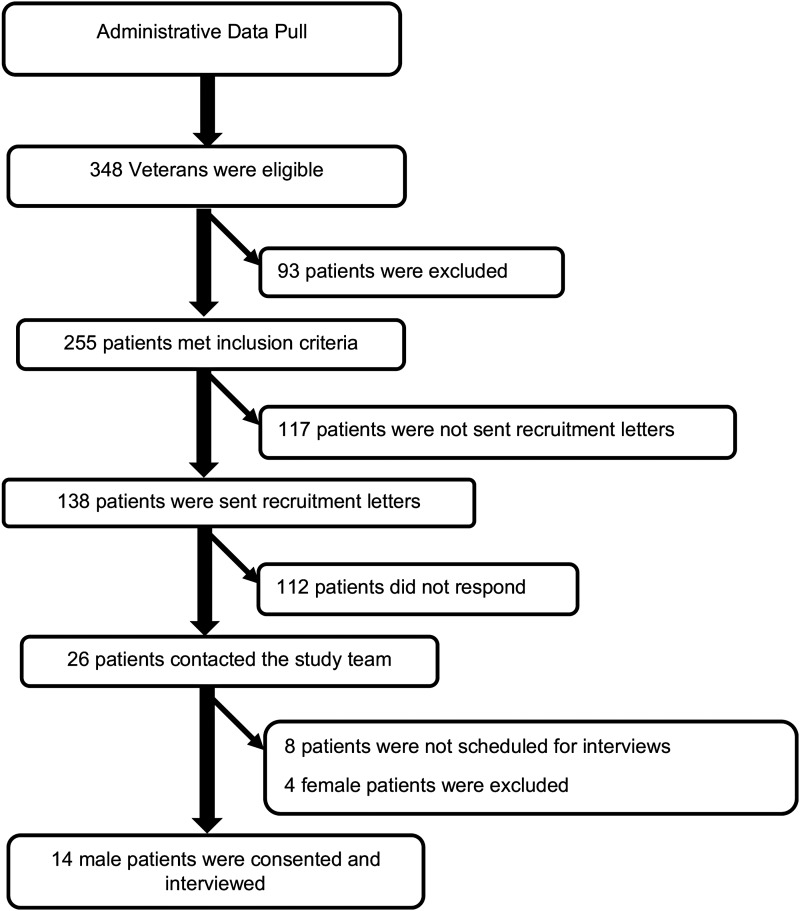

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, 743 and 348 Veterans were identified through an administrative data-pull for our MWM or bariatric surgery groups, respectively. Twenty-nine patients participating in MOVE! and 26 patients who were referred for bariatric surgery contacted the study team in response to recruitment letters. Of the 55 interested patients, 25 were scheduled and interviewed. As seen in Table 1, MWM patients were more likely to be black (27% versus 14%), have a graduate degree or higher (36% versus 21%), and have a house income greater than $100,000 (18% versus 8%).

FIG. 1.

Recruitment of male veterans participating in a medical weight management program.

FIG. 2.

Recruitment of male veterans referred for bariatric surgery.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Male Veterans Who Participated in Veteran Affairs Medical Weight Management Program or Who Were Referred for Bariatric Surgery

| MWM participants (n = 11) | Referred for bariatric surgery (n = 14) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 61.9 (SD 5.6) | 56.1 (SD 9.5) |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||

| White | 64 | 79 |

| Black or African American | 27 | 14 |

| Hispanic | 9 | 0 |

| Marital status (%) | ||

| Married | 64 | 50 |

| Single, never married | 27 | 21 |

| Divorced/separated | 9 | 21 |

| Highest level of education completed (%) | ||

| Postgraduate work or graduate degree | 36 | 21 |

| Bachelor's degree (BA or BS) | 9 | 0 |

| Associate degree (AA or AS) or trade/technical/vocational school | 18 | 21 |

| High school graduate or equivalent, or some college credit, but no degree | 27 | 36 |

| Some high school | 9 | 7 |

| Current work status (%) | ||

| Working full time or part time | 9 | 21 |

| Unemployed, searching for work | 0 | 7 |

| Retired | 45 | 21 |

| Disabled | 45 | 50 |

| Annual household income before taxes or any other deductions (%) | ||

| Greater than $100,000 | 18 | 8 |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 36 | 54 |

| $25,000–$49,000 | 18 | 15 |

| Less than $25,000 | 27 | 23 |

| Declined to answer | 0 | 0 |

MWM, medical weight management; SD, standard deviation.

Three themes emerged among both groups: (1) improving physical health, (2) improving psychological health, (3) and enhancing quality of life. Two themes were present among patients seeking bariatric surgery: (1) fear of death (2) and having exhausted all other weight loss options. Patients pursuing MWM expressed a sense of control over their weight and wanted to exhaust other weight loss options before considering bariatric surgery. In contrast, patients pursuing bariatric surgery described their experience as “running out of time” to recover the health that they had lost. Each theme along with representative quotes is characterized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quote Matrix of Patients Pursuing Medical Weight Management or Bariatric Surgery

| Themes | MWM patients | Bariatric surgery patients |

|---|---|---|

| Improving physical health | “I wanted to have control of my diabetes and I wanted to make sure that I had a better handle on my blood pressure and on heart disease.” (68 y/o) | “I don't wanna have to constantly be a slave to insulin.” (57 y/o) |

| “It was a wakeup call, since they wanted to put me on medication and I didn't want to be on medication.” (70 y/o) | ||

| Improving psychological health | “I was very depressed and uncomfortable and I couldn't, my quality of life had almost, ultimately deteriorated to nothing and I was a couch potato and then when I went to bed, I hated to go to bed at night cause I knew I couldn't sleep.” (64 y/o) | “I guess, I kinda started slipping on it, you know just activities of daily living. I wasn't showering as often, just wasn't motivated as far as personal hygiene.” (39 y/o) |

| “To be comfortable in my own skin. I mean if you get right down to the basic facts of it, to be comfortable with who I'm seeing in the mirror to a much more extent. You know I didn't feel, as big as I was, that I had anything to offer the dating world or to a social life or and my social life is very limited like I said before. Now, let alone being three or four hundred pounds and having that stigma put on you as well.” (48 y/o) | ||

| “I got bigger and bigger and it wasn't making sense. And then my clothes didn't fit no more so I was mad at that.” (59 y/o) | ||

| “I wanted to be able to sit in a theater without crowding the person next to me. Being fat is not fun. You know, it's not something I enjoyed. It's not something I expected anybody around me to understand. I just wanted to be more normal.” (69 y/o) | ||

| Enhancing quality of life | “I was in the store and I saw this really fat lady, and I was like you know, what, she couldn't even walk, and I'm like, that's not going to be me. And then that's really what kind of motivated me to kinda take matters and get things going.” (68 y/o) | “I couldn't walk up and down the steps in my house. I have a basement where my grandkids play and they, I got a lot of things set up there. And I wasn't able to go up and down the steps for over a year.” (68 y/o) |

| “I couldn't breathe. I couldn't get dressed. I was stopping two or three times to breathe. I was having trouble just being alive.” (68 y/o) | ||

| “I can't do the things I used to do. And I think most of it's based on my weight. You know. Going hiking and things like that, it's difficult when you're carrying another pack that's not a pack, you know.” (40 y/o) | ||

| “I've always worked with athletic type things outside. I love outdoor and indoor sports. So I wanted to get back to doing some of those things that I once did.” (64 y/o) | ||

| “I miss being active. I used to rock climb, scuba dive, I was in the Marines. You know, I mean I enjoyed that. Now, I'm exhausted, can't play with my kids, you know I mean that's ten and six, that's the greatest time to be a kid.” (40 y/o) | ||

| Fear of death | Not reported | “At the rate I was gaining weight, I couldn't see living very much longer, ‘cause I was probably going to end up having a heart attack.” (67 y/o) |

| There wasn't anything that was going to be any worse. I had already given up on the fact that I was going to be dying in the next months. I thought, well, okay [surgery] is an option, let's try it (68 y/o) | ||

| Having exhausted all other weight loss options | “I could control the weight if I just applied myself, rather than depending on something like (surgery) as an intervention.” (68 y/o) | “I knew if I continued down the path that I had, I wasn't going to be around. I knew I was in trouble. I wasn't getting better. I was doing worse all the time. And there was nothing I was doing that was doing better for me. So I needed [surgery].” (68 y/o) |

| “I know my body pretty well. And the times that I've had surgery on my body, I knew I had to have it. I just don't see right now having surgery on something that I can control myself.” (64 y/o) |

MWM, medical weight management; y/o, years old.

Improving physical health

Patients pursuing MWM spoke of “controlling” their weight, diabetes, or getting “a better handle” on their heart disease. MWM patients also described their desire to avoid medications. Motivations of patients pursuing MWM focused more on prevention of future health issues or worsening of current health concerns, while patients pursuing bariatric surgery focused on directly intervening to stop physical health issues. For example, patients pursuing bariatric surgery spoke of “getting rid of” physical health issues such as diabetes or sleep apnea.

Improving psychological health

Both groups discussed their loss of interest in performing daily activities and symptoms of depression as reasons to participate in treatment. Both groups of patients also discussed their desire to improve their body self-image and self-esteem. Patients in the MWM group had difficulty accepting their physical body image as they gained weight. In contrast, patients interested in bariatric surgery described the stigma of obesity. They also described obesity as a barrier to their self-esteem and achieving a normal life.

Enhancing quality of life

Both groups described wanting to be more active. Patients in the MWM group described wanting to return to activities in which they previously participated and to feel more comfortable performing daily activities. Patients referred for bariatric surgery discussed their inability to perform certain daily activities such as walking or playing with their children as motivators to pursue bariatric surgery. Both groups described their fears of being physically limited by their weight. Patients pursuing MWM discussed their fear of losing physical independence. Patients pursuing bariatric surgery described the loss of their physical independence in their daily lives.

Another motivation to improve quality of life was the desire to reduce chronic joint pain and gain mobility. Only the MWM group expressed the desire not to be a physical burden on others as a motivator for weight loss.

Fear of death

Fear of death as a result of obesity-related health issues was a strong motivator for patients in the bariatric surgery group as they shared a conviction that they would die if they did not lose weight. One patient discussed the fear of having an acute health-related issue he could not recover from. Another patient described how difficult his life had become due to chronic respiratory issues, which motivated him to consider surgery, “Nothing could be as worse as I was going through. This is a chance to get some help, let's do it (age 68, surgery).” Fear of death was not a theme that was present among patients participating in MWM.

Having exhausted all other weight loss options

Patients pursuing bariatric surgery described failing multiple weight loss attempts, which included diet, physical activity, and weight loss medications. Bariatric surgery patients had exhausted all other weight loss options and were motivated to try a more permanent weight loss method to recover their health. If they did not pursue surgery and continued down their current path, they feared they would die.

In contrast, when asked if bariatric surgery was a weight loss option they would consider, patients in the MWM group did not feel a sense of urgency and felt they had not yet exhausted all of their weight loss options. Many patients in the MWM group believed that their weight was not high enough to consider surgery. Other patients felt that they could still lose weight on their own with diet and exercise or weight loss medications. One patient commented, “I'd like to try to do this without [surgery]. A pill, I could understand. So, I can go along with that. I like trying it first” (age 60, MWM).

Discussion

We investigated motivations to pursue MWM or bariatric surgery among men with severe obesity. Both groups were motivated by the desire to improve their physical and psychological health and enhance their quality of life. Patients who were referred for bariatric surgery were motivated by the fear of death and by having exhausted all weight loss options. MWM patients wanted to attempt other weight loss options before considering bariatric surgery.

Both MWM and bariatric surgery patients placed importance on physical health and independence. Bariatric surgery patients wanted to gain back the physical independence they had lost, while MWM patients feared losing the physical independence they currently maintained. Hankey's single-gender study of interviews of males with overweight and obesity revealed that improving physical health was a key motivating factor for weight loss.14 Brink and Ferguson's qualitative interviews with participants with overweight and obesity had similar findings, describing maintaining physical health as an impetus for losing weight.6 One mixed-gender study by Peacock et al. regarding the experiences of people with severe obesity pursuing bariatric surgery found that quality of life centering on physical health was the most frequently reported motivation for surgery.15

Both bariatric surgery and MWM study groups placed an importance on improving psychological health. Other studies have found psychological health to be an important motivator. In their mixed-methods study, Munoz et al. found that participants with severe obesity, seeking bariatric surgery, were motivated to improve their body image and self-esteem.16 Similarly, Wee's secondary analysis of patients with severe obesity found that males pursued bariatric surgery due to experiencing weight stigma.9 However, no single-gender study of men with severe obesity describes improving psychological health as a motivator for seeking bariatric surgery. Improving body image is less common as a motivator for patients seeking MWM in the literature. Yoong's mixed-gender survey study assessing normal, overweight, and obesity-related patients' motivations for MWM reported that <4% of patients with obesity chose improving appearance as a primary motivator for weight loss.17 In interviews with people with overweight and obesity, Al-Mohaimeed et al. found that the desire to have an ideal body image was a primary motivator for only 16% of its participants.5 Only 2 males with obesity mentioned appearance as a motivator for weight loss in Brink and Ferguson's mixed-gender study among 76 men who were seeking to lose weight.6 Hankey's secondary analysis reported that “improved appearance” was the primary reason for weight loss for men 30–40 years of age, while younger men (18–29 years old) ranked this second.14

Both MWM and bariatric surgery patients in our study cited quality of life as a driving force for pursuing weight loss. Improving physical health and body image were the two biggest drivers for males with obesity seeking MWM in Al-Mohaimeed's mixed-gender study.5 Patients described being motivated to seek MWM by improving quality of life, and in particular, by their increasing loss of independence, which supports our study findings.5 Two mixed-gender studies noted that functionality was a motivator for participants with obesity and severe obesity pursuing bariatric surgery.8,9 In particular, Wee found that males were motivated by poor physical functioning.9

Our study supports existing mixed-gender literature suggesting that patients were motivated to pursue surgery to prevent death or extend their lifespan.15 Nevertheless, literature on fear of death as a motivator to pursue surgery is limited and there are no single-gender studies that describe the fear of death among males. Patients pursuing MWM believed that they had not exhausted all other options and wished to lose weight without surgery. This is described by Wharton's mixed-gender survey study, in which patients with severe obesity, who pursued MWM rather than bariatric surgery, were confident of future weight success using a nonsurgical option.18 No single-gender study discusses exhausting all other weight loss options as a motivation for seeking MWM.

Identifying and understanding the motivations of males pursuing obesity treatment options are critical because these findings can inform providers about what matters to patients who are considering obesity treatment. Patients pursuing bariatric surgery described their experiences with failing physical health and deteriorating quality of life. They also discussed their fear of death. Providers can apply these patient stories to weight loss treatment conversations with patients. Further, a better understanding of patient motivations will allow providers and researchers to develop and test educational interventions designed to improve obesity treatment decision-making. For example, information about how quality of life may improve with bariatric surgery or MWM would be important to include in this type of intervention because patients have indicated that it is important to them.

This study has several limitations. Our population comprised older male Veterans, who are not representative of the typical bariatric surgery patient in the United States. Veterans have more economic hardship, service-connected disabilities, and higher illness burden.19 In addition, MOVE! is an MWM program that is unique to the VA. While the core goals of promoting behavioral changes coupled with other treatment options likely align with the goals of other MWM programs, there may be programmatic differences that affect the representativeness of our MWM experience.

Our results demonstrate that multiple factors motivate males with severe obesity to pursue weight loss treatments, including improving physical and psychological health and enhancing quality of life. Bariatric surgery patients were also driven by a fear of death and felt they had exhausted all other weight loss options. MWM patients believed they had more time to pursue other treatment options. These factors should be discussed when providers are educating patients about the obesity treatment options and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Effort on this study and article was made possible by an American College of Surgeons George H.A. Clowes Career Development Award and a VA Career Development Award to Dr. L.M.F. (CDA 015-060). Dr. C.I.V. was supported by a VA Career Scientist Award (RCS 14-443). The views represented in this article represent those of the authors and not those of the VA or the U.S. Government.

Appendix 1.

Obesity-Related Comorbidities

| Comorbidity | ICD-9 code* |

|---|---|

| Diabetes | 249.00, .01, .10, .11, .20, .21, .30, .31, .40, .41, .40, .51, .60, .61, .70, .71, .80, .81, .90, .91, 250.00, .02, .10, .12, .20, .22, .30, .32, .40, .42, .50, .52, .60, .62, .63, .70, .72, .73, .80, .82, .90, .92 |

| Hypertension | 401.0, 405.1, 401.9 |

| GERD | 530.81, 530.11, 787.1, 530.85 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 327.23, 780.57, 780.51, 780.53 |

| Coronary artery disease | 414.01, 402.00–402.91, 404.00–404.93, 429.2, 401.1, 414.xx |

| Dyslipidemia | 272.4, 272.00, 272.2, 272.1 |

Codes were identified in both inpatient and outpatient diagnosis tables within CDW and were within 2 years of first MOVE! visit.

MOVE!, Veteran Affairs medical weight management program

Appendix 2.

MOVE! Visit Identification

| MOVE! visit criteria | Type of visit | MOVE! visit identification |

|---|---|---|

| MOVE! visit inclusion criteria | Group, Individual, TeleMOVE!, Phone follow-up | Defined using primary stopcodes 372 and 373 OR the following stopcode combinations: 372 + 147, 373 + 147, 372 + 324, and 373 + 324 |

| MOVE! visit exclusion criteria | Physical therapy visit | Defined using primary or secondary stopcode 202 |

The MOVE! visit was within the date range 7/1/2014-6/30/2015 and was identified in both outpatient visit tables within CDW.

Appendix 3.

Inclusion criteria

| Bariatric surgery procedure codes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Bariatric surgery procedure* | ICD-9 code | CPT code |

| Biliopancreatic diversion | 43.7, 45.91 | 43633, 43845 |

| Open Roux-en-Y-gastric bypass | 44.39, 44.31 | 43846, 43847 |

| Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y-gastric bypass | 44.38 | 43644 |

| Laparoscopic vertical sleeve gastrectomy | 43.82 | 43775 |

| Open & laparoscopic adjustable gastric band | 44.69, 44.95 | 43843, 43770 |

Bariatric surgery or bariatric surgery referral must be within the date range 1/1/2011-6/1/2016.

Identified in both inpatient and outpatient surgical procedure tables within CDW

| Bariatric referral identification criteria | ||

| Bariatric surgery referral identification | Identified by the presence of an outpatient bariatric surgery consult and querying provider consult reason notes that denoted referral | |

| MOVE! visit identification combinations used to identify our cohort of patients, who were referred for bariatric surgery and/or underwent bariatric surgery | ||

| MOVE! visit criteria | Type of visit | MOVE! visit identification* |

| MOVE! visit inclusion criteria | Group, Individual, TeleMOVE!, Phone follow-up | Defined using primary stopcodes 372 and 373 OR the following stopcode combinations: 372 + 147, 373 + 147, 372 + 324, and 373 + 324 |

| MOVE! visit exclusion criteria | Physical therapy visit | Defined using primary or secondary stopcode 202 |

A MOVE! visit must be within 2 years of either the bariatric surgery date or the bariatric consult date.

Identified in both inpatient and outpatient visit tables within CDW

Appendix 4. Patient Interview Guide: Medical Weight Management

Introduction Following Consent Process

Thank you for talking with me today. As I mentioned before, my name is Sally. I am a researcher with Dr. Funk's team, and we are trying to understand how Veterans make decisions about weight loss options. You are being interviewed because we are interested in your experience with weight loss programs inside and outside of the VA system.

-

I.

Initial Discussions about Weight Management

Can you think back to the first time you spoke with a VA provider about losing weight? Whom did you speak to and what was that discussion like?

-

What kinds of weight loss options did you discuss?

Diet, exercise, or medications?

Which of the options suggested had you tried before? What was the outcome of that?

If your provider gave you new weight loss options to try, what was the outcome of that?

Which other VA providers did you talk to about weight loss options? (i.e. Cardiology, Endocrinology, and Orthopedics)?

Which of the options suggested had you tried before? What was the outcome of that?

If your provider gave you new weight loss options to try, what was the outcome of that?

What kinds of health conditions were you dealing with that you were hoping to address through weight loss? How were those health conditions affecting your life at that time?

-

-

II.

MOVE! experience

Our records indicate that you have participated in at least one session of MOVE!, the weight loss program offered by the VA. Do you remember participating in this program? Can you tell me how you made the decision to use MOVE! and how your experience was?

Do you remember who first told you about the MOVE! program?

What were you hoping to achieve through the MOVE! program?

How much weight did you think you would lose in MOVE!?

What kind of changes did you expect to see in your health, such as your blood pressure or other health issues? Comorbidity resolution (CAD, OSA, Hyplip, DM, Osteoarthritis, etc), QOL improvement? Effects on how you take medications?

-

Can you tell me about any hesitations you might have had with participating in MOVE!?

-

○ E.g. Not losing much weight; not being able to attend very many sessions; location; and being embarrassed in front of others

How did your actual experience compare to your goals? Did you achieve what you wanted to? Why or why not?

-

Overall, what about the MOVE! program worked well? (listen for support from other Veterans, learning about diet and exercise, and being held accountable by someone else)?

What about the MOVE! program did not work as well? (listen for not losing much weight; not being able to attend very many sessions; location; and being embarrassed in front of others)

-

III.

Non-MOVE! weight management programs

We are also interested whether you have participated in other weight loss programs outside the VA such as Weight Watchers or similar programs. Have you ever participated in a program like that? Can you tell us about those? [For each one]

How did you envision your overall health changing after going through that program?

How much weight did you think you would lose in MOVE!? What about comorbidity resolution (CAD, OSA, Hyplip, DM, Osteoarthritis, etc), QOL improvement, and medication improvement

How did your actual experience compare to your goals? Did you achieve what you wanted to? Why or why not?

-

IV.

Bariatric surgery consideration

Now I would like to discuss weight loss surgery as a treatment option. Have you ever heard of weight loss surgery or know someone who had it? What is your understanding of how weight loss surgery works? Can you tell me about that?

What positive things have you heard (weight loss, improved diabetes, etc)?

What negative things have you heard (complications and weight regain)?

If did not mention: Have you ever spoken with family or friends about weight loss surgery?

Tell me about any discussion you might have had with your primary care or other health care provider about weight loss surgery.

Who brought it up?

What did you discuss?

Were you ever interested in pursuing surgery?

YES- How did you pursue it? Can you tell me more about that?

NO- What prevented you from pursuing it? Can you tell me more about that?

Are you still continuing to try to lose weight?

- If Yes, how?

○ Commercial/MOVE!/MEDS/weight loss surgery

That concludes our interview. Is there anything else you want to tell me about your experience with MOVE! or weight loss options in VA? Thank you so much for your time today

ADMINISTER EXIT SURVEY

Patient Interview Guide: Bariatric Surgery

Introduction Following Consent Process

Thank you for talking with me today. As I mentioned before, my name is Sally. I am a researcher with Dr. Funk's team, and we are trying to understand how Veterans make decisions about weight loss options. You are being interviewed today because we are interested in your experience with bariatric surgery.

-

I.

Medical Weight Management

Before we discuss bariatric surgery, I want to talk about the weight loss journey that led you there. I want you to think back to before you considered bariatric surgery. Did you ever talk to a physician or other health care worker about nonsurgical weight loss strategies, including diet, exercise, or medications?

Which physicians?

What kind of options did you discuss?

Had you tried any of those options suggested to you before?

Were there certain health conditions you had that you were hoping to address through weight loss? What were they? How were those health conditions affecting your life at that time?

What types of options did you try based on their recommendations?

What worked/did not work?

Did you ever participate in the MOVE! program or other nonsurgical weight loss program?

Tell me about your experience in that program

What about the program worked well? What did not work as well?

Lost/gained weight- And why do you think that is? Why do you think you were/were not successful?

At the time, what were some goals you wanted to achieve through attending MOVE? How did you envision your overall health improving after going through weight loss treatment?

Weight loss, comorbidity resolution, QOL improvement, and medication improvement

Do you believe you were able to achieve those goals?

You talked about the good things you hoped would happen as a result of participating in MOVE!, Were there any concerns you had about participating (like you might not be able to attend meetings, might not lose weight, or fear that it would not help?)

Excessive weight loss or regain, complications, and logistics of participating (e.g. difficult to attend meetings)

Did you experience any of the concerns you mentioned while going through MOVE!?

-

II.

Making the Decision to Undergo Bariatric Surgery

Now I would like to hear more about your experience with the bariatric program. Can you tell me how you learned about bariatric surgery and the process you went through to learn more about it?

Who brought it up?

Do you remember who referred you to the bariatric surgery program?

Was your primary care provider involved? Were there any other doctors involved in these discussions?

What did you discuss with the provider that was referring you for bariatric surgery?

Did you have to meet any requirements to get the surgery?

Can you tell me about your experience with the bariatric surgery program?

How was your experience with the Bariatric surgeon at Jesse Brown? Did you learn anything new?

At that time, what were your goals in having bariatric surgery? What did you hope to achieve by undergoing bariatric surgery? What did you hope would happen as a result of the surgery? (How did you envision your health improving?)

QOL, weight loss, medicines, comorbidity resolution, risks/complications, weight regain, and other

What were your biggest concerns about undergoing bariatric surgery?

QOL, excessive or inadequate weight loss, risks/complications, weight regain, difficulty with logistics (attending preoperative visits and attending follow-up visits), and maintaining weight loss

Can you tell me about your experience leading up to the surgery?

How did you prepare for surgery in the weeks and months leading up to it?

-

III.

Postoperation (if underwent)

Now I would like to talk to you about your experience after bariatric surgery. Can you take me through your surgery as well as the first few days and weeks after your surgery? What was that experience like?

How did you feel? What was difficult? What was not so difficult?

Pain, diet, social support, travel, child care, etc.

What were you instructed to do in terms of your diet, exercise regimen, and medications?

Would that experience have deterred you at all from getting bariatric surgery had you known what it would be like?

Tell me about your follow-up care. What medical providers did you see after surgery?

How often? Was it helpful? Do you wish you had more regular contact?

Primary Care, MOVE!, Health Psychology, Group support, Nutrition

Did you have support or help from your family, friends, or others during your recovery? What was that like?

Gym, online support groups, and psychologist

How did that impact your recovery (positive/negative)?

Earlier you mentioned that your goals for undergoing bariatric surgery were X. Do you feel like you met those goals? How? Why? Why not?

Weight loss, comorbidity resolution, QOL improvement, and medication improvement

-

IV.

Reflection (if underwent)

Overall, was surgery what you thought it would be?

If no, what was different than you expected? Did anything surprise you about surgery and recovery?

If you were advising other patients who were considering bariatric surgery, what are a few things that you think all patients need to know before proceeding with bariatric surgery?

If you had to do it all over again, would you undergo bariatric surgery?

What could have been improved with respect to your bariatric surgery experience in the VA?

-

V.

Postdecision ( No surgery)

Chose not to undergo:

Overall, what were the main reasons why you felt bariatric surgery was not a good fit for you?

Once you had decided that bariatric surgery was not the right path for you, what resources did you utilize at the VA (if any)?

Were denied surgery/did not meet criteria by the bariatric program

How did you feel once you learned that you did not meet the criteria for the bariatric program?

What do you wish you had known?

Once bariatric surgery was no longer an option, what kinds of resources have you utilized or pursued at the VA (if any)?

-

VI.

Reflection (No surgery)

f you were advising other patients who were considering bariatric surgery, what are a few things that you think all patients need to know before considering bariatric surgery?

What could have been improved with respect to your bariatric surgery experience in the VA?

Thank you so much for talking with me today.

ADMINISTER EXIT SURVEY

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults—The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res 1998;6 Suppl 2:51s–209s [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pagoto SL, Schneider KL, Oleski JL, Luciani JM, Bodenlos JS, Whited MC. Male inclusion in randomized controlled trials of lifestyle weight loss interventions. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20:1234–1239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hampp C, Kang EM, Borders-Hemphill V. Use of prescription antiobesity drugs in the United States. Pharmacotherapy 2013;33:1299–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fuchs HF, Broderick RC, Harnsberger CR, et al. Benefits of bariatric surgery do not reach obese men. J laparoendoscc Adv Surg Tech A 2015;25:196–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Al-Mohaimeed AA, Elmannan AAA. Experiences of barriers and motivators to weight-loss among Saudi people with overweight or obesity in Qassim region—A qualitative study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2017;5:1028–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brink PJ, Ferguson K. The decision to lose weight. West J Nurs Res 1998;20:84–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Libeton M, Dixon JB, Laurie C, O'Brien PE. Patient motivation for bariatric surgery: Characteristics and impact on outcomes. Obes Surg 2004;14:392–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brantley PJ, Waldo K, Matthews-Ewald MR, et al. Why patients seek bariatric surgery: Does insurance coverage matter? Obes Surg 2014;24:961–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wee CC, Davis RB, Jones DB, et al. Sex, race, and the quality of life factors most important to patients' well-being among those seeking bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2016;26:1308–1316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software; Melbourne, Austrailia: QSR International Pty Ltd; Version 11, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London, UK: Sage Publications, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc, 1994, pp.1–352 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hankey CR, Leslie WS, Lean ME. Why lose weight? Reasons for seeking weight loss by overweight but otherwise healthy men. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26:880–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peacock JC, Perry L, Morien K. Bariatric patients' reported motivations for surgery and their relationship to weight status and health. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2018;14:39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Munoz DJ, Lal M, Chen EY, et al. Why patients seek bariatric surgery: A qualitative and quantitative analysis of patient motivation. Obes Surg 2007;17:1487–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yoong SL, Mariko C, Sanson-Fisher R, D'Este C. A cross-sectional study assessing the self-reported weight loss strategies used by adult Australian general practice patients. BMC Fam Pract 2012;13:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wharton S, Serodio KJ, Kuk JL, Sivapalan N, Craik A, Aarts MA. Interest, views and perceived barriers to bariatric surgery in patients with morbid obesity. Clin Obes 2016;6:154–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rogers WH, Kazis LE, Miller DR, et al. Comparing the health status of VA and non-VA ambulatory patients: The veterans' health and medical outcomes studies. J Ambul Care Manage 2004;27:249–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]