Abstract

Adult pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a rare and malignant mesenchymal tumor. Recently, we developed a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) model of adult pleomorphic RMS. In the present study, we evaluated the efficacy of tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium (S. typhimurium) A1-R combined with caffeine (CAF) and valproic acid (VPA) on the adult RMS PDOX. An adult pleomorphic RMS cell line was established from the PDOX model. Cell survival after exposure to CAF and VPA was assessed, and the IC50 value was calculated for each drug. The RMS PDOX models were randomized into five groups: untreated control; tumor treated with cyclophosphamide (CPA); tumor treated with CAF + VPA; tumor treated with S. typhimurium A1-R; and tumor treated with S. typhimurium A1-R + CAF + VPA. Tumor size and body weight was measured twice a week. VPA caused a concentration-dependent cytocidal effect. A synergistic effect of combination treatment with CAF was observed against the RMS cell line. For the in vivo study, all treatments significantly inhibited tumor growth compared with the untreated control. S. typhimurium A1-R combined with VPA and CAF was significantly more effective than CPA, VPA combined with CAF, or S. typhimurium A1-R alone and significantly regressed the tumor volume compared with day 0. These results suggest that S. typhimurium A1-R together with VPA and CAF could regresses an adult pleomorphic RMS in a PDOX model and therefore has important future clinical potential.

Introduction

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a rare and highly malignant mesenchymal tumor [1], [2]. It is a common childhood cancer comprising more than 50% of all pediatric soft tissue sarcomas (STSs). In contrast, RMS is uncommon in adults and comprises <1% of all adult malignancies. RMS accounts for 3% of all STS [3], [4]. Histologically, RMSs are classified into three major subgroups: embryonal RMS, pleomorphic RMS, and alveolar RMS. Pleomorphic RMS and alveolar RMS have poor prognosis compared with embryonal RMS [5], [6].

Most RMSs are diagnosed in patients younger than 10 years old and these patients have better outcomes compared with older patients [7], [8], [9]. Adult patients had poor prognosis, and overall survival (OS) at 5 years was <40% [5]. In contrast, 5-year OS for younger patients was >60% [10]. However, for adult patients with metastatic disease, the 5 year survival was <5% [11], [12].

Adult RMS is a highly malignant tumor with a significant incidence of metastatic recurrence [12]. Novel more effective treatment is needed for adult RMS. RMS in the adult population has a low incidence; therefore, the study of RMS in this group is challenging. Clinically-relevant mouse models of RMS could permit evaluation of tailor-made therapy based on the patient-derived tumor. We have developed the patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) nude mouse model for all major cancers [13]. Recently, we have reported a comparative study of PDOX nude mouse model and subcutaneous xenografted model of adult pleomorphic RMS [14]. The behavior of the PDOX mouse model was more similar to the patient tumor in growth and local aggressiveness.

Caffeine (CAF) (1,3,7-trimethylxanthine) is a natural stimulatory compound and shown to be effective against tumors by inducing apoptosis [15], [16], [17]. CAF can also overcome chemotherapy- or radiation-induced delays in cell cycle progression [18], [19], thereby enhancing their efficacy [20].

Valproic acid (VPA), a short-chain fatty acid, is widely used to treat epilepsy and has been reported to be a potent histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor. HDAC inhibitors can induce apoptosis, cell differentiation, autophagy, and are anti-angiogenic [21]. VPA has been used for treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome [22], melanoma [23], and solid tumors [24]. We have reported the synergistic efficacy of the combination of CAF and VPA for sarcomas [25].

The tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R (S. typhimurium A1-R), developed by our laboratory [26], is auxotrophic for Leu–Arg, which prevents it from mounting a continuous infection in normal tissues. S. typhimurium A1-R was shown to be effective against primary and metastatic tumors in PDOX models of major cancers [27], [28], [29], [30].

In the present study, we evaluated the efficacy of S. typhimurium A1-R alone and in combination with CAF and VPA on a PDOX model of adult pleomorphic RMS.

Materials and Methods

Animal Care

Athymic nu/nu nude mice (AntiCancer Inc., San Diego, CA), 4- to 6-week old, were used in this study [14]. All animal studies were conducted with an AntiCancer Inc., Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol specifically approved for this study and in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Animals under Assurance Number A3873-1 [14]. Animal suffering was avoided by using anesthesia and analgesics for all surgical experiments. Detailed protocols of handling animals, feeding, anesthesia, injection, and humane endpoint criteria were described in previous publication [14].

Patient-Derived Tumor

A 68-year-old male diagnosed with pleomorphic RMS in a large primary right-high-thigh tumor underwent surgical resection at the Department of Surgery, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). He did not receive any chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgery. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient as part of a UCLA Institutional Review Board (IRB #10-001857)-approved protocol [14]. Briefly, the subcutaneous tumor was harvested and divided into 3-4mm3 fragments and one fragment was inserted in the left biceps femoris muscle using the technique of surgical orthotopic implantation (SOI) [14].

Surgical Orthotopic Implantation for Establishment of PDOX Model

Detailed protocols for obtaining a fresh sample of the tumor of the patient, its transportation to the laboratory at AntiCancer Inc., tumor fragmentation, subcutaneous implantation in nude mice, establishing a PDOX model, and wound closure were previously described [14].

Primary Culture of Patient-Derived Tumor

After the RMS was grown and established in nude mice, the grown tumors were harvested and were cut into small fragments (1 mm or less). Then fragments were placed in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) into a 25 cm2 sterile flask. The cell culture was rinsed the next day with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice to remove nonadherent cells and excess tissue in the flask. The medium was changed every 3–4 days thereafter.

Growth Inhibition Assay

Cellular viability was assessed using the WST-8 dye reduction assay. Cells were seeded in 96-well flat-bottomed microplates (100 μL/well) at a 5 × 104 cells/mL density, incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and exposed to various concentrations of tested compounds for 72 h. For each concentration, at least 8 wells were used. After incubation with the test compounds, 10 μl WST-8 solution was added to each well. The microplates were further incubated for 3 h at 37 °C, and absorption was measured using a microprocessor-controlled microplate reader (SunriseTM; TECAN, San Joes, CA, USA) at 450 nm. Cell-survival fractions were calculated as the percentage of untreated control cells. IC50 values were derived from concentration–response curves.

Calculation of Combination Index

The specific interaction between CAF and VPA on the RMS cell lines was evaluated by the combination index (CI) assay using CalcuSyn software from ComboSyn Inc. (New Jersey, USA), with the method of Chou and Martin [31]. In this analysis, synergy was defined as a CI < 1.0, antagonism as a CI > 1.0, and additivity as CI values not significantly different from 1.0.

Preparation and Administration of S. typhimurium A1-R

GFP-expressing S. typhimurium A1-R bacteria (AntiCancer Inc.,) were grown overnight in LB medium (Fisher Sci., Hanover Park, IL, USA) and then diluted 1:10 in LB medium. Bacteria were harvested at late-log phase, washed with PBS, and then diluted in PBS. S. typhimurium A1-R was injected intravenously. A total of 5 × 107 CFU S. typhimurium A1-R in 100 μl PBS was administered to each mouse [30], [32], [33].

Confocal Microscopy

The FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used for high-resolution imaging. Fluorescence images were obtained using the 20×/0.50 UPlan FLN and 40×/1.3 oil Olympus UPLAN FLN objectives [34].

Distribution of S. typhimurium A1-R in Adult Pleomorphic RMS PDOX Mouse

Six PDOX mouse models were treated with S. typhimurium A1-R-GFP (5 × 107 CFU/100 μl, i.v., once) when tumor volume reached 500 mm3. The PDOX tumors and tibialis anterior muscle of the affected limb were resected on day 1 and day 3 from three mice. The distribution of S. typhimurium A1-R was accessed by confocal imaging with the FV1000 [35]. Random three fields were accessed for each specimen.

Treatment Study Design in the PDOX Model of Adult Pleomorphic RMS

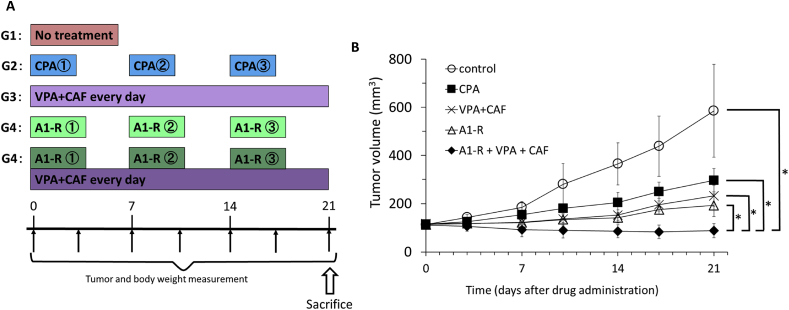

PDOX mouse models were randomized into four groups of eight mice each when tumor volume reached 100 mm3: G1, control without treatment; G2, treated with cyclophosphamide (CPA) (140 mg/kg, intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, weekly, for 3 weeks); G3, treated with CAF (100 mg/kg, i.p., daily, for 3 weeks) combined with VPA (500 mg/kg, i.p., daily for 3 weeks); G4, S. typhimurium A1-R (5 × 107 CFU/100 μl, i.v., weekly, for 3 weeks); and G5, S. typhimurium A1-R combined with CAF and VPA (5 × 107 CFU/100 μl, i.v., weekly, for 3 weeks, 100 mg/kg, i.p., daily for 3 weeks and 500 mg/kg, i.p., daily for 3 weeks, respectively). Tumor size and body weight was measured with calipers and a digital balance twice a week. Tumor length, width, and mouse body weight was measured twice per week. Tumor volume was calculated by the following formula: Tumor volume (mm3) = length (mm) × width (mm) × width (mm) × 1/2. Data were presented as mean ± SD.

Results

In Vitro Combination Effect of CAF and VPA on Adult Pleomorphic RMS Cell in Culture

The cytotoxic activity of CAF and VPA was determined in an adult pleomorphic RMS cell line which was established from a patient-derived xenograft. Cells were incubated for 72 h with each compound. Cell survival was evaluated as described in the Materials and Methods. To evaluate the potential combined effect of CAF and VPA, the CI values were determined using the WST-8 assay. Addition of 0.5 mM CAF in 1 mM VPA enhanced anti-proliferation activity against adult pleomorphic RMS cells (Figure 1, Table 1). In addition, the CI values were significantly <1 which revealed synergy at all explored concentrations in the adult pleomorphic RMS cell line (Table 2). Thus, we found a synergistic effect for the combination of CAF and VPA in the adult pleomorphic RMS cell line.

Figure 1.

Effect of caffeine (CAF) and valproic acid (VPA) on adult pleomorphic RMS cell in culture. Growth inhibitory activity of CAF and VPA or their combination against an adult pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma cell line AC-RMS01.

Table 1.

IC50 Value of Valproic Acid Against Rhabdomyosarcoma Cells with and Without Adding 0.5 mM and 1 mM of Caffeine. AC-RMS01 Cells were incubated with each drug for 72 h and then assessed via the WST-8 assay

| VPA IC50 (μg/mL) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| +CAF 0.5 mM | +CAF 1 mM | ||

| AC-RMS01 | 353.6 ± 32.9 | 204.9 ± 20.2** | 156.1 ± 23.7** |

** p<0.001.

Table 2.

CI Value of Combination of Caffeine and Valproic Acid

| Drug concentration |

CI | Drug concentration |

CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAF | VPA | CAF | VPA | ||

| 0.5 | 50.0 | 0.69641 | 1.0 | 50.0 | 0.80347 |

| 0.5 | 100.0 | 0.75105 | 1.0 | 100.0 | 0.83614 |

| 0.5 | 250.0 | 0.84027 | 1.0 | 250.0 | 0.94098 |

| 0.5 | 500.0 | 0.84129 | 1.0 | 500.0 | 0.89964 |

| 0.5 | 1000.0 | 0.8963 | 1.0 | 1000.0 | 0.96722 |

The CI values were calculated in each combination ratio. The CI values of <1, 1, or >1 indicate synergism, additively, and antagonism, respectively.

Tumor Targeting of S. typhimurium A1-R-GFP in an Adult Pleomorphic RMS PDOX Mouse Model

Tumor targeting of S. typhimurium A1-R-GFP was demonstrated by confocal imaging with the FV1000 on day 1 and day 3 after intravenous injection of S. typhimurium A1-R-GFP (Figure 2). The mean fluorescence intensity of S. typhimurium A1-R-GFP of the PDOX tumor on day 1 and day 3 was 4.63 × 105 and 6.57 × 106, respectively (P = 0.017; Figure 3A). The fluorescence area of S. typhimurium A1-R-GFP of the PDOX tumor on day 1 and day 3 was 23.2 ± 6.4 μm2 and 89.1 ± 27.0 μm2, respectively (P = 0.045; Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Fluorescence imaging of Salmonella typhimurium A1-R-GFP. Fluorescence confocal imaging of S. typhimurium A1-R-GFP targeting the adult pleomorphic RMS PDOX. Bars: 12.5 μm.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence of Salmonella typhimurium A1-R-GFP targeting the adult pleomorphic RMS PDOX. (A) Fluorescence intensity of S. typhimurium A1-R-GFP on the adult pleomorphic RMS PDOX. (B) Fluorescence area of S. typhimurium A1-R-GFP on the adult pleomorphic RMS PDOX.

S. typhimurium A1-R-GFP was not detected by the FV1000 both on day 1 and day 3 in the tibialis anterior muscle of affected limb (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Effect of CPA, VPA, and CAF Combination with S. typhimurium A1-R on the Adult Pleomorphic RMS PDOX Mouse Model

On day 21 after initiation of treatment, mean tumor volume of each group was measured: control (G1): 585.6 ± 193.1 mm3; CPA (G2): 297.3 ± 48.6 mm3; VPA + CAF (G3): 232.9 ± 43.9 mm3; S. typhimurium A1-R (G4): 193.0 ± 46.4 mm3; S. typhimurium A1-R combined with VPA and CAF (G5): 88.3 ± 29.1 mm3 (Figure 4A and B). All treatments significantly inhibited tumor growth compared with the untreated control (Figure 4): (CPA: P = 0.0019; VPA combined with CAF: P = 0.0005; S. typhimurium A1-R: P = 0.0002; S. typhimurium A1-R combined with VPA and CAF: P < 0.0001). S. typhimurium A1-R combined with VPA and CAF was significantly more effective than either CPA (P < 0.0001), VPA combined with CAF (P < 0.0001) or S. typhimurium A1-R alone (P < 0.0001) (Figure 4B). S. typhimurium A1-R combined with VPA and CAF significantly regressed the tumor volume compared with day 0 (P = 0.03) (Figure 4B). There were no animal deaths in any group. The body weight of treated mice was not significantly different in any group.

Figure 4.

(A) Treatment scheme. (B) Efficacy of cyclophosphamide (CPA), VPA combined with CAF, Salmonella typhimurium A1-R (A1-R) and A1-R combined with VPA and CAF on the adult pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma PDOX. *P < 0.0001. Tumor volume was measured at the indicated time points after the onset of treatment. n = 8 mice/group.

Histology

High-power photomicrographs of the original patient tumor demonstrated solid sheets of cancer cells characterized by pleomorphic, hyperchromatic, enlarged nuclei with coarse chromatin and moderate amounts of lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. Numerous mitotic figures, including atypical forms, are present (Figure 5A). A high-power view of the orthotopically implanted tumor demonstrated identical features including pleomorphic, hyperchromatic, enlarged nuclei with coarse chromatin and moderate amounts of lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. Numerous mitotic figures, including atypical forms, are also present. The histology of the -untreated PDOX tumor closely matched the patient's tumor with the cells of both looking very similar (Figure 5B), demonstrating the fidelity of the PDOX tumor. Tumors treated with CPA comprised viable cells without apparent necrosis or inflammatory changes (Figure 5C). Tumors treated with CAF combined with VPA and treated with S. typhimurium A1-R show changes in cancer cell shapes and reduced cellularity (Figure 5D and E). Tumors treated with CAF combined with VPA and S. typhimurium A1-R show apparent tumor necrosis with tissue fibrosis (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Tumor histology. H & E-stained section of the original patient tumor (A); untreated PDOX tumor (B); PDOX tumor treated with CPA (C); PDOX tumor treated with VPA combined with CAF (D); PDOX tumor treated with Salmonella typhimurium A1-R (E); and PDOX tumor treated with CAF combined with VPA and S. typhimurium A1-R (F). Scale bars: 80 μm.

Discussion

Bone sarcomas and STS are rare and heterogeneous group of cancers distinguished into more than 100 subtypes. Doxorubicin (DOX) and cisplatinum (CDDP) are still the standard and most effective therapeutics after four decades. For advanced sarcoma, patient treatment outcomes are unsatisfactory. Clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of novel systemic treatment including targeted and immune therapy in sarcoma have been limited because of the rarity and heterogeneity of these tumors.

The response rates of STSs to chemotherapy are relatively low (20–30%). Patients who respond to systemic therapy have significantly improved outcomes [35]. PDX models have provided a way for more clinically-relevant individualized mouse models of sarcoma that recapitulate local tumor behavior and mimic tumor-specific drug sensitivity. However, subcutaneous models of cancer rarely metastasize and few PDX models replicate advanced disease states [13].

PDOX models of sarcoma behave quite similar to patient sarcoma with regard to recurrence after surgery [14], metastasis [36], and invasively grow to surrounding tissues [14]. These properties present the opportunity to test multiple therapeutic agents [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], including targeted therapy [38] and experimental therapy such as novel platinum agents [43], and tumor-targeting S. typhimurium A1-R [46], [47], [48] in a preclinical model, without the patient suffering from the potential toxicity and morbidity of ineffective drugs. In the present study, S. typhimurium A1-R combined with CAF and VPA regressed an adult pleomorphic RMS PDOX model.

Cell cycle arrest is crucial for cell differentiation. p21 is a cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor gene which is important regulator of the cell cycle. VPA induces suppression of cyclin–CDK complexes through acetylation of histone H3 level in p21 promoter and blockage of phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein, resulting in G0/G1 arrest [50], [51], [52]. S. typhimurium A1-R decoys quiescent cancer cells in tumors from G0/G1 to S/G2/M phase with subsequent apoptosis [53]. CAF may induce the apoptosis of cancer cells arrested by S. typhimurium A1-R by inducing mitotic catastrophe [20]. The histological data (Figure 5) show reduced cellularity in all treatment groups with the greatest reduction in the group treatment with S. typhimurium A1-R combined with CAF and VPA. These data are consistent with the tumor regression in this group and indicate extensive apoptosis. Future experiments will use specific apoptosis markers and will test the individual and combined effect of these interventions on apoptosis.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that S. typhimurium A1-R combined with VPA and CAF could regress an adult pleomorphic RMS in a PDOX model and therefore has important future clinical potential for patients.

Conflict of Interest

K.I., K.K., Q.H., S.L., Y.T., T.K., K.M., M.M., T.H., and R.M.H. are or were unsalaried associates of AntiCancer Inc. MZ is the employee of AntiCancer Inc. AntiCancer Inc. uses PDOX models for contract research. The authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the memory of AR Moosa, MD; Sun Lee, MD; Professor Li Jiaxi, and Masaki Kitajima, MD.

Contributor Information

Shree Ram Singh, Email: singhshr@mail.nih.gov.

Hiroyuki Tsuchiya, Email: tsuchi@med.kanazawa-u.ac.jp.

Robert M. Hoffman, Email: all@anticancer.com.

References

- 1.Stout A.P. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the skeletal muscles. Ann Surg. 1946;123:447–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dagher R., Helman L. Rhabdomyosarcoma: an overview. The Oncologist. 1999;4:34–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari A., Dileo P., Casanova M., Bertulli R., Meazza C., Gandola L., Navarria P., Collini P., Gronchi A., Olmi P. Rhabdomyosarcoma in adults. A retrospective analysis of 171 patients treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2003;98:571–580. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemal A., Siegel R., Ward E., Murray T., Xu J., Smigal C., Thun M.J. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:106–130. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Little D.J., Ballo M.T., Zagars G.K., Pisters P.W., Patel S.R., El-Naggar A.K., Garden A.S., Benjamin R.S. Adult rhabdomyosarcoma: outcome following multimodality treatment. Cancer. 2002;95:377–388. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furlong M.A., Mentzel T., Fanburg-Smith J.C. Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma in adults: a clinicopathologic study of 38 cases with emphasis on morphologic variants and recent skeletal muscle-specific markers. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:595–603. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raney R.B., Anderson J.R., Barr F.G., Donaldson S.S., Pappo A.S., Qualman S.J., Wiener E.S., Maurer H.M., Crist W.M. Rhabdomyosarcoma and undifferentiated sarcoma in the first two decades of life: a selective review of intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study group experience and rationale for Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study V. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:215–220. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raney R.B., Maurer H.M., Anderson J.R., Andrassy R.J., Donaldson S.S., Qualman S.J., Wharam M.D., Wiener E.S., Crist W.M. The intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study group (IRSG): major lessons from the IRS-I through IRS-IV studies as background for the current IRS-V treatment protocols. Sarcoma. 2001;5:9–15. doi: 10.1080/13577140120048890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi D., Anderson J.R., Paidas C., Breneman J., Parham D.M., Crist W. Age is an independent prognostic factor in rhabdomyosarcoma: a report from the soft tissue sarcoma Committee of the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;42:64–73. doi: 10.1002/pbc.10441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crist W., Gehan E.A., Ragab A.H., Dickman P.S., Donaldson S.S., Fryer C., Hammond D., Hays D.M., Herrmann J., Heyn R. The third intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:610–630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.3.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esnaola N.F., Rubin B.P., Baldini E.H., Vasudevan N., Demetri G.D., Fletcher C.D., Singer S. Response to chemotherapy and predictors of survival in adult rhabdomyosarcoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:215–223. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200108000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins W.G., Hoos A., Antonescu C.R., Urist M.J., Leung D.H., Gold J.S., Woodruff J.M., Lewis J.J., Brennan M.F. Clinicopathologic analysis of patients with adult rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer. 2001;91:794–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman R.M. Patient-derived orthotopic xenografts: better mimic of metastasis than subcutaneous xenografts. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(8):451–452. doi: 10.1038/nrc3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Igarashi K., Kawaguchi K., Kiyuna T., Murakami T., Miwa S., Nelson S.D., Dry S.M., Li Y., Singh A., Kimura H. Patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) mouse model of adult rhabdomyosarcoma invades and recurs after resection in contrast to the subcutaneous ectopic model. Cell Cycle. 2017;16(1):91–94. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2016.1252885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coffee, tea, mate, methylxanthines and methylglyoxal, IARC working group on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Lyon, 27 February to 6 March 1990. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1991;51:1–513. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levi-Schaffer F., Touitou E. Xanthines inhibit 3T3 fibroblast proliferation. Skin Pharmacol. 1991;4:286–290. doi: 10.1159/000210963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.He Z., Ma W.Y., Hashimoto T., Bode A.M., Yang C.S., Dong Z. Induction of apoptosis by caffeine is mediated by the p53, Bax, and caspase 3 pathways. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4396–4401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tolmach L.J., Jones R.W., Busse P.M. The action of caffeine on x-irradiated Hela cells. I. Delayedinhibition of DNA synthesis. Radiat Res. 1977;71:653–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lau C.C., Pardee A.B. Mechanism by which caffeine potentiates lethality of nitrogen mustard. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:2942–2946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.9.2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miwa S., Yano S., Tome Y., Sugimoto N., Hiroshima Y., Uehara F., Mii S., Kimura H., Hayashi K., Efimova E.V. Dynamic color-coded fluorescence imaging of the cell-cycle phase, mitosis, and apoptosis demonstrates how caffeine modulates cisplatinum efficacy. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:2454–2460. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marks P.A. The clinical development of histone deacetylase inhibitors as targeted anticancer drugs. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19:1049–1066. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2010.510514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raffoux E., Cras A., Recher C., Boëlle P.Y., de Labarthe A., Turlure P., Marolleau J.P., Reman O., Gardin C., Victor M. Phase 2 clinical trial of 5-azacitidine, valproic acid, and all-trans retinoic acid in patients with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome. Oncotarget. 2010;1:34–42. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rocca A., Minucci S., Tosti G., Croci D., Contegno F., Ballarini M., Nolè F., Munzone E., Salmaggi A., Goldhirsch A. A phase I-II study of the histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid plus chemoimmunotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:28–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munster P., Marchion D., Bicaku E., Lacevic M., Kim J., Centeno B., Daud A., Neuger A., Minton S., Sullivan D. Clinical and biological effects of valproic acid as a histone deacetylase inhibitor on tumor and surrogate tissues: phase I/II trial of valproic acid and epirubicin/FEC. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2488–2496. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Igarashi K., Yamamoto N., Hayashi K., Takeuchi A., Kimura H., Miwa S., Hoffman R.M., Tsuchiya H. Non-toxic efficacy of the combination of caffeine and valproic acid on human osteosarcoma cells in Vitro and in orthotopic nude-mouse models. Anticancer Res. 2016 Sep;36(9):4477–4482. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.10992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murakami T., DeLong J., Eilber F.C., Zhao M., Zhang Y., Zhang N., Singh A., Russell T., Deng S., Reynoso J. Tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R in combination with doxorubicin eradicate soft tissue sarcoma in a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) model. Oncotarget. 2016;7:12783–12790. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao M., Yang M., Li X.M., Jiang P., Baranov E., Li S., Xu M., Penman S., Hoffman R.M. Tumor-targeting bacterial therapy with amino acid auxotrophs of GFP-expressing Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:755–760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408422102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao M., Geller J., Ma H., Yang M., Penman S., Hoffman R.M. Monotherapy with a tumor-targeting mutant of Salmonella typhimurium cures orthotopic metastatic mouse models of human prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10170–10174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703867104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao M., Yang M., Ma H., Li X., Tan X., Li S., Yang Z., Hoffman R.M. Targeted therapy with a Salmonella typhimurium leucine-arginine auxotroph cures orthotopic human breast tumors in nude mice. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7647–7652. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang Y., Tome Y., Suetsugu A., Zhang L., Zhang N., Hoffman R.M., Zhao M. Determination of the optimal route of administration of Salmonella typhimurium A1-R to target breast cancer in nude mice. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:2501–2508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chou T.C., Martin N. ComboSyn Inc; Paramus, (NJ): 2005. CompuSyn for drug combinations: PC software and user's guide: a computer program for quantitation of synergism and antagonism in drug combinations, and the determination of IC50 and ED50 and LD50 values. A. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y., Miwa S., Zhang N., Hoffman R.M., Zhao M. Tumor targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R arrests growth of breast-cancer brain metastasis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:2615–2622. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uchugonova A., Zhao M., Zhang Y., Weinigel M., König K., Hoffman R.M. Cancer-cell killing by engineered Salmonella imaged by multiphoton tomography in live mice. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4331–4339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oshiro H., Kiyuna T., Tome Y., Miyake K., Kawaguchi K., Higuchi T., Miyake M., Zhang Z., Razmjooei S., Barangi M. Detection of metastasis in a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) model of undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma with red fluorescent protein. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:81–85. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Igarashi K., Murakami T., Kawaguchi K., Kiyuna T., Miyake K., Zhang Y., Nelson S.D., Dry S.M., Li Y., Yanagawa J. A patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) mouse model of a cisplatinum-resistant osteosarcoma lung metastasis that was sensitive to temozolomide and trabectedin: implications for precision oncology. Oncotarget. 2017;8:62111–62119. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawaguchi K., Igarashi K., Miyake K., Kiyuna T., Miyake M., Singh A.S., Chmielowski B., Nelson S.D., Russell T.A., Dry S.M. Patterns of sensitivity to a panel of drugs are highly individualised for undifferentiated/unclassified soft tissue sarcoma (USTS) in patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) nude-mouse models. J Drug Target. 2019;27:211–216. doi: 10.1080/1061186X.2018.1499748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiyuna T., Tome Y., Murakami T., Miyake K., Igarashi K., Kawaguchi K., Oshiro H., Higuchi T., Miyake M., Sugisawa N. A combination of irinotecan/cisplatinum and irinotecan/temozolomide or tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R arrest doxorubicin- and temozolomide-resistant myxofibrosarcoma in a PDOX mouse model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;505:733–739. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.09.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kiyuna T., Murakami T., Tome Y., Igarashi K., Kawaguchi K., Miyake K., Miyake M., Li Y., Nelson S.D., Dry S.M. Doxorubicin-resistant pleomorphic liposarcoma with PDGFRA gene amplification is targeted and regressed by pazopanib in a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft mouse model. Tissue Cell. 2018;53:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higuchi T., Kawaguchi K., Miyake K., Oshiro H., Zhang Z., Razmjooei S., Wangsiricharoen S., Igarashi K., Yamamoto N., Hayashi K. The combination of gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel as a novel effective treatment strategy for undifferentiated soft-tissue sarcoma in a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) nude-mouse model. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;111:835–840. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miyake K., Kiyuna T., Miyake M., Kawaguchi K., Zhang Z., Wangsiricharoen S., Razmjooei S., Oshiro H., Higuchi T., Li Y. Gemcitabine combined with docetaxel precisely regressed a recurrent leiomyosarcoma peritoneal metastasis in a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;509:1041–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higuchi T., Miyake K., Sugisawa N., Oshiro H., Zhang Z., Razmjooei S., Yamamoto N., Hayashi K., Kimura H., Miwa S. Olaratumab combined with doxorubicin and ifosfamide overcomes individual doxorubicin and olaratumab resistance of an undifferentiated soft-tissue sarcoma in a PDOX mouse model. Cancer Lett. 2019;451:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miyake K., Kiyuna T., Kawaguchi K., Higuchi T., Oshiro H., Zhang Z., Wangsiricharoen S., Razmjooei S., Li Y., Nelson S.D. Regorafenib regressed a doxorubicin-resistant Ewing's sarcoma in a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) nude mouse model. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019;83:809–815. doi: 10.1007/s00280-019-03782-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Igarashi K., Kawaguchi K., Murakami T., Kiyuna T., Miyake K., Yamamoto N., Hayashi K., Kimura H., Nelson S.D., Dry S.M. A novel anionic-phosphate-platinum complex effectively targets an undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma better than cisplatinum and doxorubicin in a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) Oncotarget. 2017;8:63353–63359. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Igarashi K., Kawaguchi K., Murakami T., Kiyuna T., Miyake K., Nelson S.D., Dry S.M., Li Y., Yanagawa J., Russell T.A. Intra-arterial administration of tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R regresses a cisplatin-resistant relapsed osteosarcoma in a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) mouse model. Cell Cycle. 2017;16:1164–1170. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1317417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murakami T., Kiyuna T., Kawaguchi K., Igarashi K., Singh A.S., Hiroshima Y., Zhang Y., Zhao M., Miyake K., Nelson S.D. The irony of highly-effective bacterial therapy of a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) model of Ewing's sarcoma, which was blocked by Ewing himself 80 years ago. Cell Cycle. 2017;16:1046–1052. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1304340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Igarashi K., Kawaguchi K., Kiyuna T., Miyake K., Miyake M., Singh A.S., Eckardt M.A., Nelson S.D., Russell T.A., Dry S.M. Tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R is a highly effective general therapeutic for undifferentiated soft tissue sarcoma patient-derived orthotopic xenograft nude-mouse models. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;497:1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.02.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Igarashi K., Kawaguchi K., Kiyuna T., Miyake K., Miyake M., Li S., Han Q., Tan Y., Zhao M., Li Y. Tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R combined with recombinant methioninase and cisplatinum eradicates an osteosarcoma cisplatinum-resistant lung metastasis in a patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) mouse model: decoy, trap and kill chemotherapy moves toward the clinic. Cell Cycle. 2018;17:801–809. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2018.1431596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miyake K., Kawaguchi K., Miyake M., Zhao M., Kiyuna T., Igarashi K., Zhang Z., Murakami T., Li Y., Nelson S.D. Tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R suppressed an imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumor with c-kit exon 11 and 17 mutations. Heliyon. 2018;4:e00643. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miyake K., Murakami T., Kiyuna T., Igarashi K., Kawaguchi K., Miyake M., Li Y., Nelson S.D., Dry S.M., Bouvet M. The combination of temozolomide-irinotecan regresses a doxorubicin-resistant patient-derived orthotopic xenograft (PDOX) nude-mouse model of recurrent Ewing's sarcoma with a FUS-ERG fusion and CDKN2A deletion: direction for third-line patient therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8:103129–103136. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shapiro G.I. Cyclin-dependent kinase pathways as targets for cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1770–1783. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.7689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee Y.M., Sicinski P. Targeting cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases in cancer: lessons from mice, hopes for therapeutic applications in human. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2110–2114. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.18.3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnstone R.W., Licht J.D. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer therapy: is transcription the primary target? Cancer Cell. 2003;4:13–18. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yano S., Zhang Y., Zhao M., Hiroshima Y., Miwa S., Uehara F., Kishimoto H., Tazawa H., Bouvet M., Fujiwara T., Hoffman R.M. Tumor-targeting Salmonella typhimurium A1-R decoys quiescent cancer cells to cycle as visualized by FUCCI imaging and become sensitive to chemotherapy. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:3958–3963. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.964115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]