Abstract

HIV-1 protease is one of the prime targets of agents used in antiretroviral therapy against HIV. However, under selective pressure of protease inhibitors, primary mutations at the active site weaken inhibitor binding to confer resistance. Darunavir (DRV) is the most potent HIV-1 protease inhibitor in clinic; resistance is limited, as DRV fits well within the substrate envelope. Nevertheless, resistance is observed due to hydrophobic changes at residues including I50, V82 and I84 that line the S1/S1’ pocket within the active site. Through enzyme inhibition assays and a series of 12 crystal structures, we interrogated susceptibility of DRV and two potent analogs to primary S1’ mutations. The analogs had modifications at the hydrophobic P1’ moiety compared to DRV to better occupy the unexploited space in the S1’ pocket where the primary mutations were located. Considerable losses of potency were observed against protease variants with I84V and I50V mutations for all three inhibitors. The crystal structures revealed an unexpected conformational change in the flap region of I50V protease bound to the analog with the largest P1’ moiety, indicating interdependency between the S1’ subsite and the flap region. Collective analysis of protease-inhibitor interactions in the crystal structures using principle component analysis was able to distinguish inhibitor identity and relative potency solely based on vdW contacts. Our results reveal the complexity of the interplay between inhibitor P1’ moiety and S1’ mutations, and validate principle component analyses as a useful tool for distinguishing resistance and inhibitor potency.

Keywords: drug resistance, crystal structure, principal component analysis, protease inhibitor, substrate envelope

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infects roughly 37 million people globally, with over 2 million new infections and over 1 million AIDS-related deaths occurring each year1. After 30 years of research, advances in antiretroviral therapies (ARTs), combinations of small molecule inhibitors, greatly extended life expectancy for those who receive treatment2, 3. ARTs inhibit critical proteins necessary for viral replication and maturation, most commonly targeting HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and protease. Although ARTs are highly effective in most patients, the current therapies are still an imperfect solution to a complex problem, as HIV-1 can evolve to confer drug resistance through accumulation of mutations4. Primary resistance mutations, typically occurring proximal to the active site where the inhibitor binds, are selected early under selective pressure of inhibition and directly affect inhibitor binding and allow the accumulation of additional mutations. Secondary mutations can occur distal to the active site but still indirectly affect substrate processing or inhibitor binding5, 6. No HIV-1 inhibitor is resistance-proof, and modifying an inhibitor to better tolerate primary resistance mutations may help to prevent the accumulation of additional mutations7.

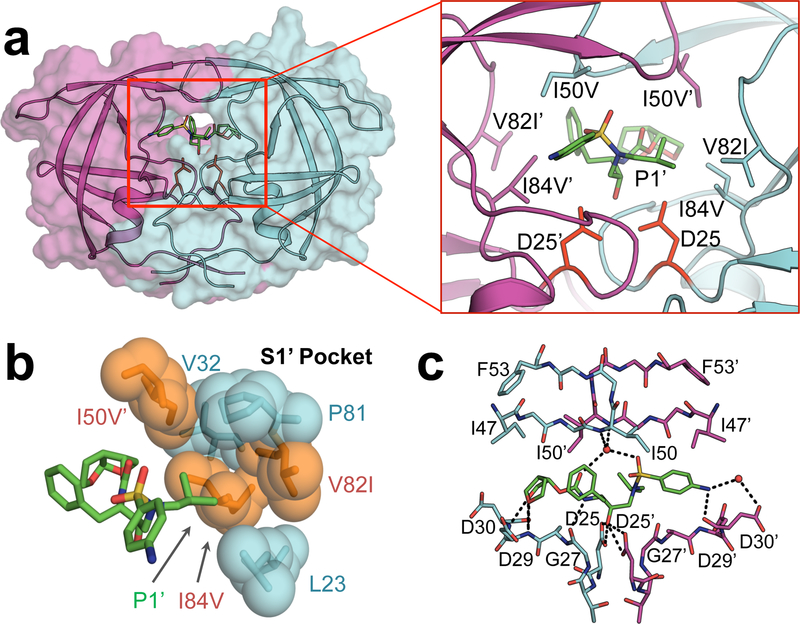

HIV-1 protease, a 99-amino acid, homodimeric, aspartyl protease8, 9 [Figure 1a], is essential for viral replication and maturation, making this enzyme an ideal drug target10, 11. The protease processes twelve unique cleavage sites on viral Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins to release individual viral proteins required for viral replication and maturation. While the cleavage sites share low amino acid sequence identity, when bound to HIV-1 protease they occupy a consensus volume termed the substrate envelope12. We have previously shown that inhibitors that fit within this volume are less prone to resistance as the protease cannot mutate to reduce inhibitor binding without compromising affinity for natural substrates13.

Figure 1.

a) Co-crystal structure of DRV (green sticks) bound to WT HIV-1 protease. Chain A (cyan) and chain B (magenta) are shown as a cartoon with a transparent surface. D25/D25’ catalytic aspartates (red) are displayed as sticks. a-insert) Residues that contribute to primary drug resistance, shown as sticks. b) Spherical representation of residues that make up the S1’ subsite / P1’ pocket. Variable residues are shown in orange. c) Hydrogen bonds (black dashes) between DRV and WT HIV-1 protease. Coordinated waters are shown as red spheres.

The most potent FDA approved protease inhibitor, darunavir (DRV) [Figure 2a], fits well inside the substrate envelope, yet resistance still occurs due to accumulation of mutations in HIV-1 protease in patient isolates14, 15. DRV is a peptidomimetic inhibitor with four major chemical moieties, denoted as P2, P1, P1’ and P2’ [Figure 2]. Highly mutated clinical isolates with 18 or more mutations in the protease have been identified, and DRV binding to these resistant proteases studied enzymatically and structurally15–20. Most of the patient-derived sequences bear a constellation of secondary mutations as well as primary mutations at the active site that confer DRV resistance, notably including I50V and I84V21–24. Mutations at I50 are often selected together with A71V mutation, which is distal from the active site but compensates for the loss of enzymatic fitness25. Thermodynamics and structural studies of DRV binding to I50V/L and A71V mutations have revealed significant loss of van der Waals (vdW) contacts between the inhibitor and protease underlying loss of binding affinity26.

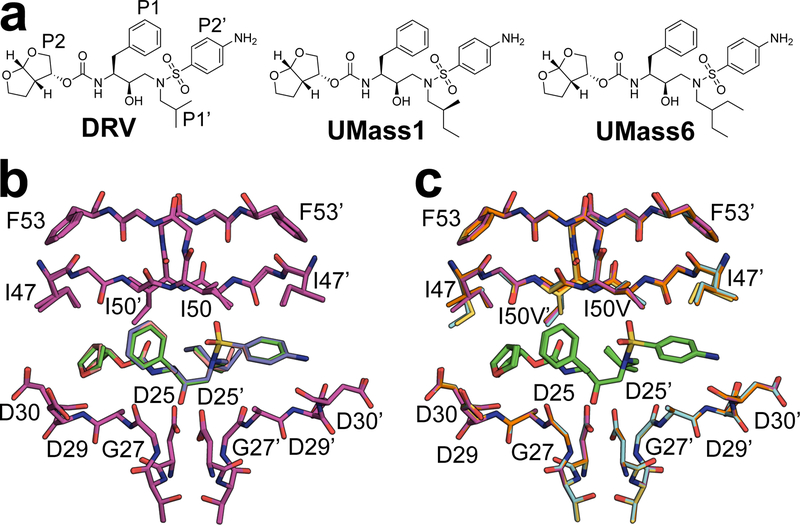

Figure 2.

a) 2D chemical structure of DRV (with peptidomimetic moieties labeled) and the two DRV analogs (UMass1 and UMass6) with modifications at the P1’ moiety. b) WT protease (magenta) inhibited by DRV (green), UMass1 (pink), and UMass6 (purple) c) DRV (green) bound to WT (magenta), I84V (cyan), V82I (orange), and I50V (gold) protease variants.

DRV and analogs have been and continue to be the subject of chemical, viral, structural and dynamics studies27. Modifications to the bis-THF P2 moiety of DRV, including fluorine decorations, expansion to tris-THF and fusion into a tri-cyclic group17, 28, 29 and additional modifications of the P1 and P2’ moiety have been shown to improve potency and resistance profiles30–32. Our computational studies suggested that P1’ and P2’ moieties of DRV could be further optimized33 while still staying within the substrate envelope. Accordingly, we previously designed, synthesized and evaluated a panel of 10 DRV analogs with varying P1’ and P2’ moieties, and demonstrated that substrate envelope-guided design can achieve improved inhibition and potency against resistant variants34. These inhibitors, named UMass1–10, have subsequently served us as tools to probe subsite interdependency35, water structure36, and structural changes in solution by NMR37. Among these analogs, UMass1 and UMass6 share the same P2’ moiety with DRV but have larger hydrophobic groups at the P1’ position [Figure 2a] leveraging the unexploited space in the S1’ pocket of the substrate envelope. Thus this set of 3 inhibitors, varying only by the size of the hydrophobic P1’ moiety, is ideal to probe the interplay between inhibitor modifications and protease mutations in the S1’ subsite. The underlying mechanism of how P1’ modifications may affect inhibitor response to resistance mutations surrounding the moiety had not been investigated.

In this work, we investigate the interdependency of potency loss for HIV-1 protease inhibitors that differ at the P1’ moiety (DRV, UMass1, and UMass6) [Figure 2a], with WT and 3 variants of HIV-1 protease bearing mutations at residues in the S1/S1’ pocket. The hydrophobic residues I84, V82 and I50 that form the S1’ pocket where the P1’ moiety binds [Figure 1] (as well as the S1 pocket, as the protease is a homodimer) are all highly variable, and mutations are implicated in many instances of drug resistance, commonly mutating to I84V, V82I, and I50V14, 38, 39 in multi-mutant protease variants. Enzyme inhibition assays were performed and a complete set of 12 crystal structures were determined for the inhibitor–protease combinations. Principal component analysis (PCA) was applied for a collective analysis of the determined structures, which was able to distinguish inhibitor potency and identity based solely on the intermolecular van der Waals contacts. Based on our results, we expect similar applications of PCA can be extended to deconvolute the major determinants underlying resistance/potency in other systems, and to develop predictive models to assess inhibitor potency in drug design.

Results

To elucidate the mechanisms of resistance and impact on potency of primary S1’ mutations, enzymatic assays and crystal structural analysis were performed with WT HIV-1 protease and 3 variants. The WT protease had the near-consensus clade B sequence of the NL4–3 strain. All three protease variants had a single mutation that altered the shape of the hydrophobic S1/S1’ pocket of HIV-1 protease: I50V, V82I and I84V. Three inhibitors, DRV with an isobutyl P1’ moiety and 2 analogs in which the P1’ moiety was extended to better fill the substrate envelope, UMass1 with a methylbutyl and UMass6 with an ethlybutyl moiety,34 were analyzed.

Enzymatic Activity of Protease Variants

The enzymatic activity of WT HIV-1 protease and chosen variants (I84V, V82I and I50V) were tested using a natural substrate sequence (MA/CA)40 [Table S1]. WT NL4–3 HIV-1 protease had a Michaelis-Menten constant, Km, of 71 ± 7 μM for cleaving this substrate, which was similar to that of I84V and V82I variants (66 ± 4 and 62 ± 4 μM, respectively). The primary resistance mutation I50V is known to reduce catalytic activity,26 and while I50V is still catalytically active, the Km value is beyond the limit of detection for this assay. A71V, a compensatory mutation that is far from the active site and almost always observed with I50V, restores the functionality to WT level (Km = 73 ± 9 μM), as previously reported.26 A time-course gel shift assay confirmed the catalytic activity of I50V single mutant, and the rescued activity of I50V/A71V variant in cleaving purified Gag polyprotein [Figure S1]. The sustained catalytic activity of proteases across all variants indicates these primary mutations can indeed appear early in drug resistance pathways without compromising substrate cleavage.

Effect of P1’ Modifications on Inhibition of Variants with Active Site Mutations

The enzyme inhibition constant (Ki) was measured to determine the potency of inhibitors against each HIV-1 protease variant [Table 1] using an optimized assay41. The optimized assay enabled Ki determination with smaller errors and lower enzyme concentrations, and gave results that were overall comparable to previously published values34. Although the assay is optimized, the lower limit of detection is about 5 pM and all 3 inhibitors were too potent to obtain a reliable value against WT protease. The V82I mutation did not confer any measurable resistance for the inhibitors, with the Ki staying below 5 pM. The I84V mutation caused a reduction in potency, with the Ki increasing to around 25 pM for DRV and UMass1, and approximately half of that for UMass6. Thus, the inhibitor with the largest P1’ moiety performed 2-fold better than the other inhibitors against I84V variant. The I50V mutation was more deleterious with Ki values increasing by two orders of magnitude relative to WT protease. Interestingly, UMass6 performed slightly worse than DRV and UMass1 (Ki = 146 ±11 versus 117 ± 6 and 131 ± 8 pM, respectively). Although both I84V and I50V mutations cause the same reduction in side chain size, these two mutations had the opposite effect on the change in potency of UMass6 compared to DRV and UMass1.

Table 1.

Enzyme inhibition constant, Ki (pM), of inhibitors against WT protease and variants with primary mutations, measured using an optimized enzymatic assay.

| Inhibitor | WT | I84V | V82I | I50V | I50V/A71V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRV | < 5 | 25.6 ± 5.6 | < 5 | 117.2 ± 5.8 | 74.5 ± 5.6 |

| UMass1 | < 5 | 26.1 ± 3.7 | < 5 | 131.3 ± 8.2 | 110.3 ± 8.8 |

| UMass6 | < 5 | 12.8 ± 3.1 | < 5 | 146.2 ± 10.7 | 100.0 ± 9.9 |

Structural Rearrangements Underlying DRV Susceptibility to Primary Resistance Mutations

To determine the structural basis of observed potency changes due to primary resistance mutations around the P1’ moiety, each protease variant was co-crystalized with each inhibitor resulting in a set of 12 crystal structures [Table S2]. All structures were solved in the same space group with a resolution of 2 Å or better and in the same NL4–3 background, affording detailed investigation of atomic interactions (our previous structures of these inhibitors34 were determined with SF-2 protease). We determined the crystal structures of DRV, UMass1 and UMass6 bound to WT HIV-1 protease of NL4–3 strain, which was also used in the enzymatic assays above.

When DRV and other peptidomimetic inhibitors bind to HIV-1 protease, the hydroxyl moiety is centered between the catalytic aspartates (D25/D25’) and the inhibitor makes a number of additional hydrogen bonding interactions with the backbone nitrogen and oxygen atoms of residues that line the active site [Figure 1c]. DRV also makes a key water-mediated interaction with the backbone nitrogen of residue 50, located at the tip of each flap. DRV’s P1 and P1’ moieties are hydrophobic and interact with hydrophobic residues/pockets in the hinge of the flaps. Inhibitor potency diminishes if any of these polar or non-polar interactions are perturbed.

DRV-bound crystal structures were compared to reveal any structural rearrangements in response to single mutations at the active site. Overall, the structures were highly similar [Figure 2]. In agreement with the maintained potency against V82I variant, the hydrogen bonding and packing of DRV at the active site was conserved in the V82I crystal structure [Figure 2b and Table 2]. The additional steric bulk of the isoleucine side chain is not directed towards the inhibitor but instead is solvent exposed, and does not perturb inhibitor binding. As in the V82I variant, the binding mode and hydrogen bonds of DRV were not altered in I84V and I50V structures [Figure 2b]. However, van der Waals (vdW) interactions with residues 84 and 84’ decreased due to I84V mutation, which was in part compensated by increased packing against I47 and V82’ [Table 2]. In the I84V variant, residues V32’ and L23’ in chain B underwent a side chain conformer change relative to WT protease [Figure S2]. In addition, residue I47 was found in an alternative rotamer in chain A, causing increased inhibitor interactions with that residue. This asymmetric compensation indicates subtle alterations in the overall packing of the inhibitor at the active site, which reduced the effect of I84V mutation on potency.

Table 2.

Change in intermolecular van der Waals (vdW) interactions between inhibitor and protease active site residues relative to WT complex. Only residues with changes greater than 0.40 kcal/mol are listed. Primed residue numbers correspond to chain B. Decrease and increase in per residue contacts with respect to WT protease are colored blue to red, respectively.

| Resi # | I84V_DRV | I84V_UMass1 | I84V_UMass6 | V82I_DRV | V82I_UMass1 | V82I_UMass6 | I50V_DRV | I50V_UMass1 | I50V_UMass6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 | 0.28 | −0.14 | −0.83 | 0.46 | 0.05 | −0.44 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.48 |

| 47 | 1.22 | 1.07 | 1.12 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 1.12 | 1.19 | −0.08 | −0.18 |

| 48 | 0.49 | 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.05 | −0.18 |

| 49 | 0.33 | −0.02 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.27 | −0.44 |

| 50 | −0.50 | −0.60 | −0.53 | −0.11 | −0.04 | 0.13 | −1.70 | −1.32 | −1.94 |

| 84 | −1.17 | −1.10 | −1.17 | −0.12 | 0.15 | −0.01 | −0.05 | 0.27 | −0.31 |

| 23’ | −0.60 | −0.33 | −0.25 | −0.06 | −0.17 | −0.11 | 0.10 | −0.09 | −0.07 |

| 25’ | −0.41 | −0.31 | −0.37 | 0.10 | 0.01 | −0.11 | −0.08 | 0.04 | −0.30 |

| 28’ | −0.55 | −0.34 | −0.28 | 0.06 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.40 | −0.47 |

| 47’ | −0.36 | −0.47 | −0.42 | 0.20 | 0.04 | −0.02 | 0.49 | 0.09 | 0.41 |

| 48’ | −0.16 | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.44 |

| 49’ | −0.09 | −0.07 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.61 |

| 50’ | −0.08 | 0.16 | −0.03 | −0.09 | 0.11 | 0.03 | −0.84 | −0.44 | 0.17 |

| 82’ | 1.17 | 1.03 | 0.83 | 0.23 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.21 |

| 84’ | −1.82 | −1.61 | −1.54 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.23 | −0.21 |

A similar repacking was also observed in the I50V–DRV structure, where increased packing against I47 in both chains compensated lost vdW interactions at residue 50. Our previous computational analysis had indicated I47 as a major modulator of DRV-protease interactions42. Thus, the structures explain why the V82I single mutation did not confer resistance to DRV, and in agreement with previous studies reveal the rearrangements in vdW packing around DRV underlying susceptibility to I50V26, 43. Importantly, intermolecular interactions are not solely altered at the site of mutation but throughout the active site, urging a more detailed structural analysis.

Structural Response to Modifying P1’ Moiety Against Primary Mutations

The larger P1’ moieties of UMass1 and UMass6 were designed to improve hydrophobic packing and increase vdW contacts with the protease while still staying within the substrate envelope34. Accordingly, the total vdW energy of intermolecular interactions between the inhibitor and protease increased by 1.6 and 4.7 kcal/mol, respectively for UMass1 and UMass6, as the P1’ moiety increased in size [Table S3]. However, the simple measure of total vdW interaction energy is not sufficient to explain the overall Ki value trends, suggesting a more comprehensive residue-based analysis may be needed to capture inhibitor potency. In the V82I structure, while DRV did not gain significant interactions compared to WT complex, UMass1 and UMass6 gained approximately 2 kcal/mol in vdW energy as their P1’ moieties directly interact, but not clash, with the sterically larger side chain. Thus, although the Ki values are below the limit of detection, structural analysis suggests that V82I mutation might confer hyper-susceptibility to UMass1 and UMass6 inhibitors; thus unlike with DRV, the V82I mutation is not likely to be selected under the pressure of these inhibitors.

The co-crystal structures of UMass1 bound to WT protease and variants were very similar to those of DRV [Figure 2c], albeit with subtle alterations. Against I84V and I50V mutations, which are located directly at the pocket where P1’ moiety binds, UMass1 experienced a similar reduction in potency as DRV [Table 1]. The UMass1–I84V structure displayed the same phenomenon of asymmetric inhibitor repacking as with DRV [Table 2]. The additional methyl group in UMass1 is oriented away from the steric space provided by the I84V mutation but still makes additional contacts with P81 and V82. When UMass1 bound I50V, there was a reduction in vdW interactions at residue 50 and 50’ as seen for DRV, but no compensation at residue 47. Instead, repacking of UMass1 increased against G49 and I84 in chain A, and residues 28–30 in chain B. However, this alternate compensation was more distributed and subtle, which may underlie the slightly worse Ki of UMass1 compared to DRV against I50V protease. Thus, the crystal structures indicate that although the potency loss against I50V is similar for DRV and UMass1, the underlying structural changes and repacking at the active site are distinct.

I50V Mutation Induces Conformational Changes in Both UMass6 and Protease Flaps

UMass6 has an even bulkier P1’ moiety than UMass1 and binds WT protease similar to DRV and UMass1 [Figure 2c] but with enhanced overall vdW interactions (−87.8 kcal/mol compared to −83.1 and −84.7, respectively; Table S3). Against I84V mutation, enhanced packing at the P1’ moiety of UMass6 resulted in overall better interactions and potency. In UMass6, the methyl groups on both branches of the P1’ moiety help UMass6 to better accommodate the steric space provided by the I84V mutation, leading to a 2-fold improvement in Ki compared to the other two inhibitors.

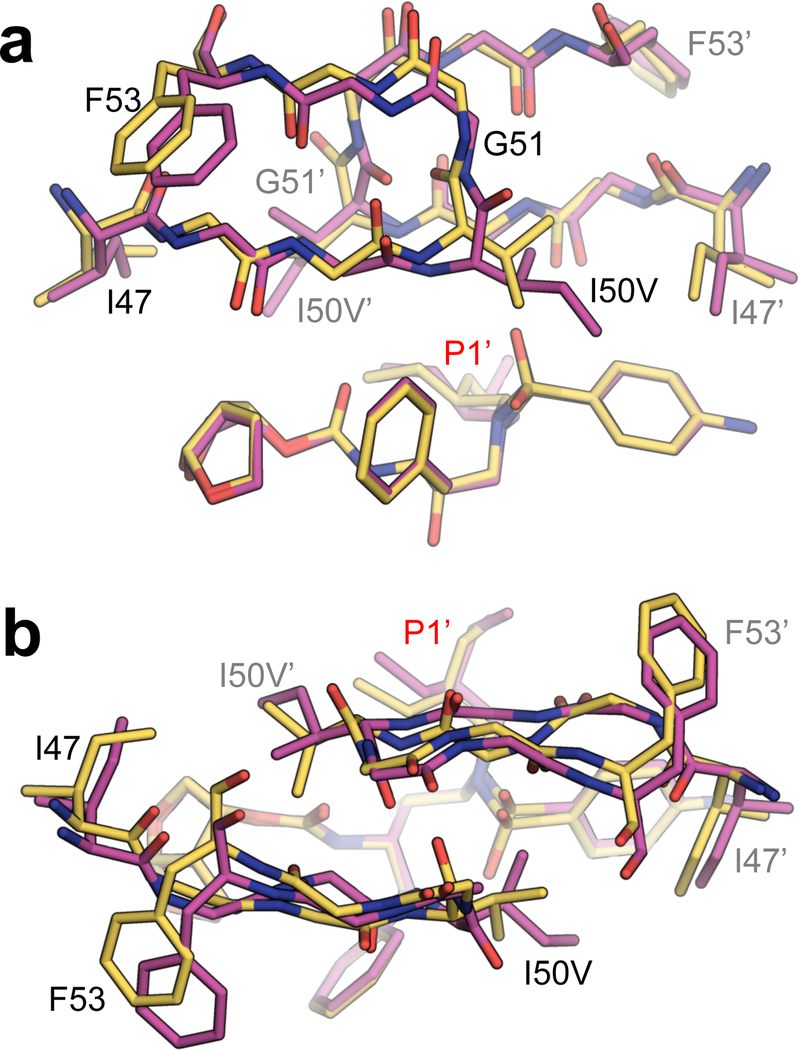

Contrary to the case of I84V mutation, UMass6 bound to the I50V variant with the lowest potency. Unexpectedly, the P1’ moiety of UMass6 in I50V protease structure adopted a completely different conformation compared to the other 11 structures [Figure 3]. In addition to this inhibitor’s unique binding conformation, the flaps in I50V protease underwent rather large-scale changes: In chain A, I47 assumed a rare rotamer to maintain interaction with the sterically smaller I50V [Figure S2]. In chain B, T80 underwent a conformational change which may affect flap-tip curling and flexibility44,45. This conformational change caused the flaps to bow outward [Figure 3c] away from UMass6, further reducing vdW contacts. Interestingly, the resulting vdW losses of UMass6 with residue 50 due to the I50V mutation were completely asymmetric, with a loss similar to DRV and UMass1 in chain A but almost no loss in chain B [Table 2]. However, there was no compensation at residue 47 interactions in either chain, due to the different conformer of I47, which resulted in a greater overall loss in vdW interactions, in agreement with the greatest potency loss observed for UMass6 against I50V mutation.

Figure 3.

The P1’ moiety of UMass6 bound to the I50V variant and the protease flaps exist in an alternate conformation. a) Superposition of WT-UMass6 (magenta) and I50V-UMass6 (gold) structures, displaying the inhibitor and the flap region. Residues 47–53 in both monomers are shown as sticks. b) The same superposition with 90° rotation to show the top view of the flap region.

Although the position of most of the flap residues were altered in the UMass6–I50V structure relative to WT complex, the typical hydrogen bond distances were not significantly perturbed [Figure S3, Table S4]. However, the flipping of the flaps caused a noticeable shift in the location of the so-called flap water [Figure S3], which is crucial for flap stabilization46, and which in turn caused the sulfonyl group to shift toward the flaps to maintain H-bond distances. The shift of the sulfonyl group fused to the aniline P2’ moiety weakened the bond formed by the conjugated water interacting with the side chain of D30 by making the overall distance longer. Weakening of inhibitor hydrogen bonding with D29-D30 has been reported to be coupled with increased flap flexibility in drug resistance due to I50V47.

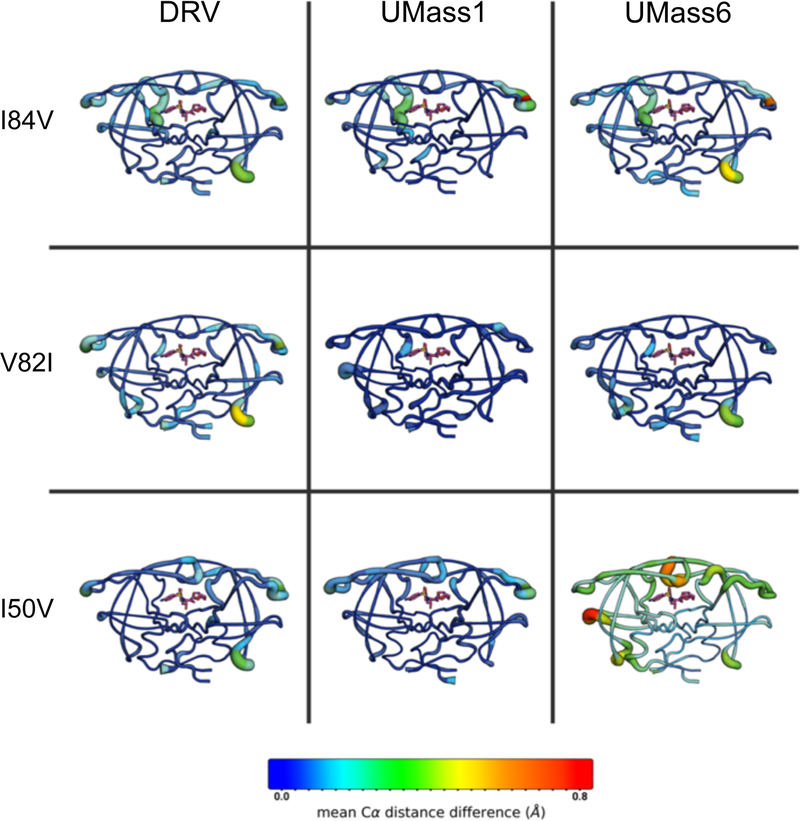

The structural rearrangements of the protease in the I50V–UMass6 structure were quantified and visualized by distance-difference matrices [Figure S4]. Distance-difference matrices measure the internal distances between alpha carbon atoms of every residue pair in a structure, then compare each distance to that in a reference structure, which in our case is the inhibitor bound to WT protease. This method detects conformational changes due to a mutation without any structural superposition bias. Comparison of the variant structures to their corresponding WT structures shows the discrepancy between the I50V–UMass6 and all the other 11 structures [Figure S4]. Mapping the distance-differences onto the 3D structure revealed that the structural changes due to I50V in the UMass6-bound protease propagated throughout the protein structure [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Cartoon-putty diagrams depicting the mean changes in C-alpha distance differences relative to WT protease crystal structure. Tube thickness and warm colors indicate larger differences.

Principle Component Analysis (PCA) of Residue-Specific Interactions

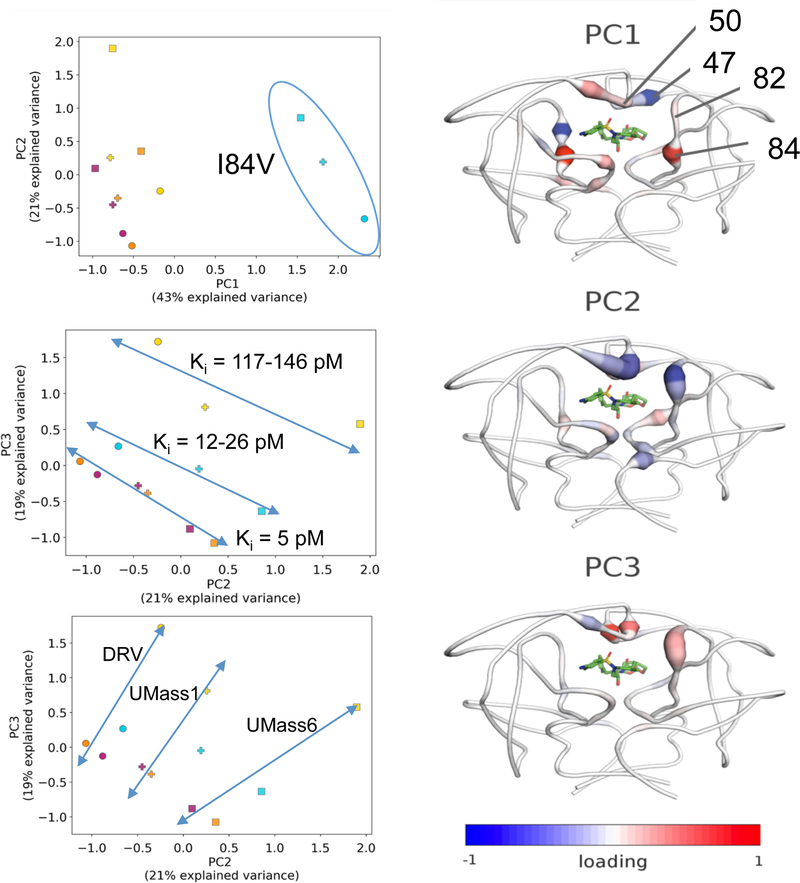

The set of 12 inhibitor–protease crystal structures and the corresponding Ki values enabled a collective analysis of the interplay between inhibitor modifications and protease mutations in the S1/S1’ subsite. First, the intermolecular vdW interaction energy with the inhibitor for each residue in a given structure was calculated for each of the 12 structures to yield a 198×12 matrix. Although this matrix contains rich information on the molecular basis of inhibitor potency, the multidimensionality and complexity of the data precludes deducing what specific properties are responsible for the observed variation. Thus, the matrix of residue-wise vdW contacts was subjected to principal component analysis (PCA) to extract principal components (PC) that best account for the variance in data. The first three principal components (PCs) accounted for 83% of the observed variance, with the first PC (PC1) accounting for approximately half (43%) of the variance [Figure S5a]. In addition to reducing the dimensionality of the dataset and, the PCs reveal what causes the variations in inhibitor–protease interactions among these structures.

The PC1 separated the structures mainly according to the protease variant, rather than inhibitor identity [Figure 5]. Significantly, structures containing the I84V primary resistance mutation of all 3 inhibitors clustered away from the remaining structures. Inspection of the loading indicated PC1 was largely determined by changes in vdW interactions between the inhibitor and residue 84 [Figure S5]. This is in agreement with our previous work that showed that mutations at residue 84 significantly alter the pattern of vdW contacts in a panel of drug resistant variants.48 Additionally, contacts between I47 and the inhibitor contributed significantly to the spread along PC1, which can assume a different side chain conformer and compensate for loss of interactions at residue 84 as explained above.

Figure 5.

Principle component analysis of vdW interactions in the 12 protease-inhibitor complexes. (left) The protease–inhibitor pairs plotted according to first and second principle components, PC1 versus PC2 (upper panel) and PC2 versus PC3 (lower panels). In the plots, circles (DRV), plus signs (UMass1), and squares (UMass 6) indicate different inhibitors and colors (magenta: WT, yellow: I50V, orange: V82I, cyan: I84V) indicate protease variant. The blue oval and straight lines are shown to guide the eye and highlight clusters. (right) The contribution of individual residues to the PCs according to the loading vector are depicted on protease backbone structure using cartoon-putty diagrams, where tube thickness indicates higher weights and warm colors are positive loading and cold colors are negative loading. Residues with the highest weights are labeled on the cartoon-putty for PC1.

The second and third principal components (PC2 and PC3) together accounted for 40% of the observed variance in inhibitor–protease vdW interactions. PC2 separated structures mostly according to inhibitor identity, rather than protease variant [Figure 5]. Inspection of the loading of PCs showed that variance at residues 84 and 50’ contributed significantly to the ordering of structures along PC2, indicating modification of inhibitor P1’ moiety caused alteration in packing against these residues [Figure S5b]. The contribution of residue 50 in chain A had the same direction for both PC2 and PC3 whereas the contributions of 84 and 50’ had the opposite direction. Contacts between the inhibitor and residues 84 and 50’ changed significantly in the presence of a small P1’ moiety but were less effected when the P1’ moiety was larger. Overall, the PCA captured the asymmetric compensation of vdW interactions observed in the crystal structures, and quantified the contribution of residue-specific interactions to the overall variance in the dataset.

Strikingly, plotting PC2 and PC3 against each other enabled separating the 12 crystal structures both according to inhibitor identity and potency [Figure 5]. All 6 inhibitor-protease pairs with <5 pM affinity clustered on a line defined by a linear combination of PC2 and PC3. Intriguingly, the I84V and I50V complexes fell on separate but parallel lines, together defining a set of 3 roughly parallel lines on the PC2-PC3 plane. These 3 lines were ordered according to experimentally measured potency, with the I84V complexes nearer to the high affinity line, followed by the I50V complexes. Additionally, 3 other roughly perpendicular lines separated the inhibitor-protease pairs according to inhibitor identity. The inhibitors were also ordered, according to the chemical similarity of their P1’ moieties as DRV-UMass1UMass6. Thus, the collective analysis of the set of 12 crystal structures using PCA enabled clustering inhibitor identity and potency based solely on per residue vdW contacts, indicating this information is sufficient to discern inhibitors.

Discussion

In this study the interplay between modifications of an inhibitor’s functional group and modifications known to confer drug resistance that surround that functional group. Specifically, we have investigated HIV-1 protease inhibitor DRV and two analogs and assessed modifications at P1’ and how these analogs interactions by three single site drug resistant variants. A set of 12 high-resolution crystal structures comprising three analogous inhibitors bound to WT protease and three variants allowed a collective analysis of inhibitor-protease interactions in modulating potency and resistance. The overall intermolecular vdW energy or hydrogen bonding was not sufficient to explain the observed inhibitor potency; thus we employed a more comprehensive and residue-based analysis. The residue-based vdW contact energies in all 12 structures was subjected to PCA, which not only identified the key residues that determined the variance in inhibitor packing but also captured the asymmetry in this variance. Rather than visual inspection or manual comparison, PCA enabled an unbiased quantitative assessment of intermolecular interactions collectively in all the 12 structures.

More significantly, clustering of the structures along major PCs was able to categorize the inhibitor-protease pairs according to inhibitor type and potency. This suggests residue-specific vdW interactions may serve as “fingerprints” to categorize and classify inhibitors bound to protease, particularly for inhibitors similar to those used here. PCA has recently been applied to overall structures of HIV-1 protease deposited in the PDB to cluster and categorize protease conformations.49, 50 As with any mathematical model, the training set (or the input data) needs to be appropriate for the purpose and expanded when possible to improve the model and enable assessing more diverse inhibitors. In addition, analyzing mutations that involve polar or charged residues will likely require analyzing intermolecular electrostatic interactions in addition to vdW contacts. Nevertheless, we found here that certain simple and linear combinations of PCs, derived from complex and multidimensional structural data, might be indicators or even predictors of inhibitor potency.

DRV and the analogs used differ only at the P1’ moiety. The larger, flexible P1’ groups of UMass1 and UMass6 were previously shown to increase potency compared to DRV in cellular assays, specifically against a panel of WT clades and drug resistant variants with many mutations34. Our results validated that larger P1’ moieties were effective against I84V and V82I mutations, but an unexpected alternative mechanism of resistance was uncovered against the I50V mutation. The I50V mutation is commonly observed in variants that are resistant to DRV, and has previously been investigated18, 24. Unlike DRV and UMass1, the P1’ group of UMass6 is large enough to be able to contribute a methyl group to interact with the destabilized hydrophobic interactions involving the flap tips. However, this interaction affects the orientation of V50, which to avoid an unfavorable side chain rotamer, induces flipping of the flaps and a rather unforeseen conformational rearrangement. A similar but distinct flap rearrangement was previously observed in response to a coevolution mutation in Gag substrate in the I50V/A71V variant, which enhances vdW interactions with the substrate51. Hence the relative flexibility of flaps in this variant might be able to enhance interactions with substrates while weakening inhibitor binding, thus contributing to conferring resistance.

Unlike the other two mutations, V82I did not confer measurable resistance against the inhibitors tested. However, crystal structures suggested that the intermolecular interactions are improved for UMass1 and UMass6 relative to WT protease, unlike for DRV. Thus, the bulkier P1’ groups in UMass inhibitors might cause hyper-susceptibility to V82I and prevent selection of this mutation on resistance pathways. However, groups larger than that in UMass1 may act as a selective pressure forcing I50V to become a dominant variant. Thus, despite high similarity, inhibitors with P1’ modifications may select distinct mutational patterns of resistance.

The analysis on three inhibitor analogs here revealed that the basic idea that a larger P1’ moiety would help the inhibitor to retain better interactions upon shortening of a side chain is not necessarily correct. Rather than a simple alteration in interactions at this subsite, there was an overall and asymmetric rearrangement of the vdW interactions throughout the active site pocket due to either I84V or I50V mutation. As intended, the bulkier P1’ moiety of UMass6 helped to retain better potency against I84V, but the reverse was the case for I50V mutation. Thus, although both I84V and I50V are primary resistance mutations with the same side chain change in the S1’ pocket, the interplay between P1’ moiety and rearrangements of inhibitor interactions were distinct, and moreover contrasting for these two mutations. These unexpected and distributed alterations in intermolecular interactions prompted the application of PCA for a collective and comprehensive analysis of the crystal structures. The analysis revealed the interplay between inhibitor modifications and structural response of the target with primary mutations underlying resistance, indicating PCA may be a useful tool to extract determinants or even predictors of inhibitor potency from complex structural information.

Materials and Methods

Protease gene construction

Protease gene construction was carried out as previously described51, 52. The NL4–3 strain has four naturally occurring polymorphisms in the protease relative to the SF2 strain27, 53. In short, the protease variant genes (I50V, V82I, I84V) were constructed using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis (Genewiz) onto NL4–3 WT protease on a pET11a plasmid with codon optimization for protein expression in Escherichia coli. A Q7K mutation was included to prevent autoproteolysis54.

Protein expression and purification

The expression, isolation, and purification of WT and mutant HIV-1 proteases used for the kinetic assays and crystallization were carried out as previously described51, 52. Briefly, the gene encoding the HIV protease was subcloned into the heat-inducible pXC35 expression vector (ATCC) and transformed into E. coli TAP-106 cells. Cells grown in 6L of Terrific Broth were lysed with a cell disruptor and the protein was purified from inclusion bodies55. The inclusion body centrifugation pellet was dissolved in 50% acetic acid followed by another round of centrifugation to remove impurities. Size exclusion chromatography was used to separate high molecular weight proteins from the desired protease. This was carried out on a 2.1-L Sephadex G-75 superfine (Sigma Chemical) column equilibrated with 50% acetic acid. The cleanest fractions of HIV protease were refolded into a 10-fold dilution of 0.05 M sodium acetate at pH 5.5, 5% ethylene glycol, 10% glycerol, and 5 mM DTT. Folded protein was concentrated down to 0.5–3mg/mL and stored. This stored protease was used in Km and Ki assays. For crystallography, a final purification was performed with a Pharmacia Superdex 75 FPLC column equilibrated with 0.05 M sodium acetate at pH 5.5, 5% ethylene glycol, 10% glycerol, and 5 mM DTT. Protease fractions purified from the size exclusion column was concentrated to 1–2 mg/mL using an Amicon Ultra-15 10-kDa device (Millipore) for crystallization.

Enzymatic Assays to Determine Km and Ki

The Km and Ki Assays were carried out as previously described40, 41. In the Km assay, a 10-amino acid substrate containing the natural MA/CA cut site with an EDANS/DABCYL FRET pair was dissolved in 8% DMSO at 40nM and 6% DMSO at 30 nM. The 30 nM of substrate was 4/5th serially diluted from 30 nM to 6 nM, including a 0 nM control. HIV protease was diluted to 120 nM and, using a PerkinElmer Envision plate reader, 5 μL was added to the 96-well plate to obtain a final concentration of 10 nM. The fluorescence was observed with an excitation at 340 nm and emission at 492 nm and monitored for 200 counts, for approximately 23 minutes. FRET inner filter effect correction was applied as previously described56. Corrected data was analyzed with Prism7.

To determine the Ki, in a 96-well plate, each inhibitor was 2/3 serially diluted from 3000 pM to 52 pM, including a 0 pM control, and incubated with 0.35 nM protein for 1 hour. A 10-amino acid substrate containing an optimized protease cut site with an EDANS/DABCYL FRET pair was dissolved in 4% DMSO at 120 μM. Using the Envision plate reader, 5 μL of the 120 μM substrate was added to the 96-well plate to a final concentration of 10 μM. The fluorescence was observed with an excitation at 340 nm and emission at 492 nm and monitored for 200 counts, for approximately 60 minutes. Data was analyzed with Prism7.

Protein Crystallization

Discovery of the condition producing reproducible co-crystals of DRV with NL4–3 WT protease was achieved using the JCSG+ screen (Molecular Dimensions), in well G11, consisting of 2 M Ammonium Sulfate with 0.1 M Bis-Tris-Methane Buffer at pH 5.5 with a protease concentration of 1.9 mg/mL with 3-fold molar excess of DRV and mixed with the precipitant solution at a 1:2 ratio. After optimization, all subsequent combinations of co-crystals were grown at room temperature by hanging drop vapor diffusion method in a 24-well VDX hanging-drop trays (Hampton Research) with protease concentrations between 1.0 to 2.4 mg/mL with 3-fold molar excess of inhibitors set the crystallization drops with the reservoir solution consisting of 23–24% (w/v) Ammonium sulfate with 0.1 M bis-Trismethane buffer at pH 5.5 set with 2 μL of well solution and 1 μL protein and microseeded with a cat whisker. Diffraction quality crystals were obtained within 1 week. As data was collected at 100 K, cryogenic conditions contained the precipitant solution supplemented with 25% glycerol.

Data Collection and Structure Solution

Diffraction data were collected and solved as previously described51, 57. Diffraction quality crystals were flash frozen under a cryostream when mounting the crystal at our in-house Rigaku_Saturn944 X-ray system. The co-crystal diffraction intensities were indexed, integrated, and scaled using HKL300058. Structures were solved using molecular replacement with PHASER59. Model building and refinement were performed using Coot60 and Phenix61. Ligands were designed in Maestro and the output sdf file was used in the Phenix program eLBOW62 to generate the cif file containing atomic positions and constraints necessary for ligand refinment. Iterative rounds of crystallographic refinement were carried out until convergence was achieved. To limit bias throughout the refinement process, five percent of the data were reserved for the free R-value calculation63. MolProbity64 was applied to evaluate the final structures before deposition in the PDB. Structure analysis, superposition and figure generation was done using PyMOL.65 X-ray data collection and crystallographic refinement statistics are presented in the Supporting Information [Table S2].

Structural Analysis and PCA

Distance-difference matrices were generated for each inhibitor-mutant protease pair to reveal structural changes relative to that inhibitor bound to wild-type protease, as previously described66. Briefly, distances between all Cα pairs in the mutant structure were calculated as an NxN matrix (N = 198 residues for HIV-1 protease), and then those corresponding distances in the wild-type structure were subtracted to construct the distance difference matrix. The mean deviation from the WT structure for each residue was then calculated by taking the average of the absolute value of all the N distance differences involving that residue, and the backbone structure was represented as a cartoon-putty with increasing thickness and warmer color for increasing deviation.

To calculate the intermolecular van der Waals (vdW) interaction energies the crystal structures were prepared using the Schrodinger protein preparation wizard67. Hydrogen atoms were added, protonation states determined and the structures were minimized. The protease active site was monoprotonated at D25. Subsequently forcefield parameters were assigned using the OPLS2005 forcefield68. Interaction energies between the inhibitor and protease were estimated using a simplified Lennard-Jones potential, as previously described69. For each protease residue, the change in vdW interactions relative to WT complex was also calculated for the mutant structures. PCA of the data matrix was performed as described earlier.43 For the calculation of the principal components, the implementation of PCA in scikit-learn was used70. Briefly, the intermolecular vdW interaction energy with the inhibitor for each residue in a given structure was calculated for each of the 12 structures to yield a 198×12 matrix. The dimensionality of the data set was then reduced using PCA to identify orthogonal linear combinations of variables, or principal components (PCs), that best account for the variance in the data. The PCs are ordered starting from first PC according to the greatest variance represented in the data, and contribution of the original variables to a given PC is represented by the loading vector.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH P01 GM109767. We would like to thank W. Royer, B. Kelch and B. Hilbert for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations Used

- DRV

darunavir

- vdW

van der Waals

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- PC

principal component

- PCA

principal component analysis

Footnotes

Ancillary Information

Supporting Information

Table of Km values; X-ray crystallography statistics; total vdW interaction energy in crystal structures; SDS-PAGE showing Gag cleavage products; supplemental methods; figures showing alignment of inhibitor-bound crystal structures and hydrogen bonds; table of hydrogen bond distances; distance-difference matrices; variance and loading of PCs.

PDB ID Codes

6DGX, 6GDY, 6GDZ, 6DH0, 6DH1, 6DH2, 6DH3, 6DH4, 6DH5, 6DH6, 6DH7, 6DH8

Authors will release the atomic coordinates and experimental data upon article publication.

REFERENCES

- [1].(2016) World Health Organization. World health statistics 2016: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals, 136. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Arts EJ, and Hazuda DJ (2012) HIV-1 antiretroviral drug therapy, Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2, a007161. DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a007161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Palmisano L, and Vella S (2011) A brief history of antiretroviral therapy of HIV infection: success and challenges, Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita 47, 44–48. DOI: 10.4415/ANN_11_01_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Abram ME, Ferris AL, Shao W, Alvord WG, and Hughes SH (2010) Nature, position, and frequency of mutations made in a single cycle of HIV-1 replication, J. Virol. 84, 9864–9878. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.00915-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wensing AM, van Maarseveen NM, and Nijhuis M (2010) Fifteen years of HIV Protease Inhibitors: raising the barrier to resistance, Antiviral Res. 85, 59–74. DOI: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Agniswamy J, Louis JM, Roche J, Harrison RW, and Weber IT (2016) Structural Studies of a Rationally Selected Multi-Drug Resistant HIV-1 Protease Reveal Synergistic Effect of Distal Mutations on Flap Dynamics, PLoS One 11, e0168616. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ghosh AK, Osswald HL, and Prato G (2016) Recent Progress in the Development of HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors for the Treatment of HIV/AIDS, J. Med. Chem. 59, 5172–5208. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Meek TD, Dayton BD, Metcalf BW, Dreyer GB, Strickler JE, Gorniak JG, Rosenberg M, Moore ML, Magaard VW, and Debouck C (1989) Human immunodeficiency virus 1 protease expressed in Escherichia coli behaves as a dimeric aspartic protease, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86, 1841–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Navia MA, Fitzgerald PM, McKeever BM, Leu CT, Heimbach JC, Herber WK, Sigal IS, Darke PL, and Springer JP (1989) Three-dimensional structure of aspartyl protease from human immunodeficiency virus HIV-1, Nature 337, 615–620. DOI: 10.1038/337615a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tozser J, Blaha I, Copeland TD, Wondrak EM, and Oroszlan S (1991) Comparison of the HIV-1 and HIV-2 proteinases using oligopeptide substrates representing cleavage sites in Gag and Gag-Pol polyproteins, FEBS Lett. 281, 77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Konnyu B, Sadiq SK, Turanyi T, Hirmondo R, Muller B, Krausslich HG, Coveney PV, and Muller V (2013) Gag-Pol processing during HIV-1 virion maturation: a systems biology approach, PLoS Comput. Biol. 9, e1003103. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika E, and Schiffer CA (2002) Substrate shape determines specificity of recognition for HIV-1 protease: analysis of crystal structures of six substrate complexes, Structure 10, 369–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kurt Yilmaz N, Swanstrom R, and Schiffer CA (2016) Improving Viral Protease Inhibitors to Counter Drug Resistance, Trends Microbiol. 24, 547–557. DOI: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Rhee SY, Taylor J, Fessel WJ, Kaufman D, Towner W, Troia P, Ruane P, Hellinger J, Shirvani V, Zolopa A, and Shafer RW (2010) HIV-1 protease mutations and protease inhibitor cross-resistance, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4253–4261. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00574-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Saskova KG, Kozisek M, Rezacova P, Brynda J, Yashina T, Kagan RM, and Konvalinka J (2009) Molecular characterization of clinical isolates of human immunodeficiency virus resistant to the protease inhibitor darunavir, J. Virol. 83, 8810–8818. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.00451-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kozisek M, Lepsik M, Grantz Saskova K, Brynda J, Konvalinka J, and Rezacova P (2014) Thermodynamic and structural analysis of HIV protease resistance to darunavir - analysis of heavily mutated patient-derived HIV-1 proteases, FEBS J. 281, 1834–1847. DOI: 10.1111/febs.12743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Agniswamy J, Shen CH, Aniana A, Sayer JM, Louis JM, and Weber IT (2012) HIV-1 protease with 20 mutations exhibits extreme resistance to clinical inhibitors through coordinated structural rearrangements, Biochemistry 51, 2819–2828. DOI: 10.1021/bi2018317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nakashima M, Ode H, Suzuki K, Fujino M, Maejima M, Kimura Y, Masaoka T, Hattori J, Matsuda M, Hachiya A, Yokomaku Y, Suzuki A, Watanabe N, Sugiura W, and Iwatani Y (2016) Unique Flap Conformation in an HIV-1 Protease with High-Level Darunavir Resistance, Front. Microbiol. 7, 61 DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yedidi RS, Garimella H, Aoki M, Aoki-Ogata H, Desai DV, Chang SB, Davis DA, Fyvie WS, Kaufman JD, Smith DW, Das D, Wingfield PT, Maeda K, Ghosh AK, and Mitsuya H (2014) A conserved hydrogen-bonding network of P2 bis-tetrahydrofuran-containing HIV-1 protease inhibitors (PIs) with a protease active-site amino acid backbone aids in their activity against PI-resistant HIV, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 3679–3688. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00107-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Agniswamy J, Shen CH, Wang YF, Ghosh AK, Rao KV, Xu CX, Sayer JM, Louis JM, and Weber IT (2013) Extreme multidrug resistant HIV-1 protease with 20 mutations is resistant to novel protease inhibitors with P1’-pyrrolidinone or P2-tristetrahydrofuran, J. Med. Chem. 56, 4017–4027. DOI: 10.1021/jm400231v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].de Meyer S, Vangeneugden T, van Baelen B, de Paepe E, van Marck H, Picchio G, Lefebvre E, and de Bethune MP (2008) Resistance profile of darunavir: combined 24week results from the POWER trials, AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 24, 379–388. DOI: 10.1089/aid.2007.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Rhee SY, Gonzales MJ, Kantor R, Betts BJ, Ravela J, and Shafer RW (2003) Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase and protease sequence database, Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 298–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Shafer RW (2006) Rationale and uses of a public HIV drug-resistance database, J. Infect. Dis. 194 Suppl 1, S51–58. DOI: 10.1086/505356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Weber IT, Kneller DW, and Wong-Sam A (2015) Highly resistant HIV-1 proteases and strategies for their inhibition, Future Med. Chem. 7, 1023–1038. DOI: 10.4155/fmc.15.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Nijhuis M, Schuurman R, de Jong D, Erickson J, Gustchina E, Albert J, Schipper P, Gulnik S, and Boucher CA (1999) Increased fitness of drug resistant HIV-1 protease as a result of acquisition of compensatory mutations during suboptimal therapy, AIDS 13, 2349–2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Mittal S, Bandaranayake RM, King NM, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalam MN, Nalivaika EA, Yilmaz NK, and Schiffer CA (2013) Structural and thermodynamic basis of amprenavir/darunavir and atazanavir resistance in HIV-1 protease with mutations at residue 50, J. Virol. 87, 4176–4184. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.03486-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Surleraux DL, Tahri A, Verschueren WG, Pille GM, de Kock HA, Jonckers TH, Peeters A, De Meyer S, Azijn H, Pauwels R, de Bethune MP, King NM, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Schiffer CA, and Wigerinck PB (2005) Discovery and selection of TMC114, a next generation HIV-1 protease inhibitor, J. Med. Chem. 48, 1813–1822. DOI: 10.1021/jm049560p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ghosh AK, Parham GL, Martyr CD, Nyalapatla PR, Osswald HL, Agniswamy J, Wang YF, Amano M, Weber IT, and Mitsuya H (2013) Highly potent HIV-1 protease inhibitors with novel tricyclic P2 ligands: design, synthesis, and protein-ligand X-ray studies, J. Med. Chem. 56, 6792–6802. DOI: 10.1021/jm400768f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ghosh AK, P, R. N., Kovela S, Rao KV, Brindisi M, Osswald HL, Amano M, Aoki M, Agniswamy J, Wang YF, Weber IT, and Mitsuya H (2018) Design and Synthesis of Highly Potent HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors Containing Tricyclic Fused Ring Systems as Novel P2 Ligands: Structure-Activity Studies, Biological and X-ray Structural Analysis, J. Med. Chem. 61, 4561–4577. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ghosh AK, Fyvie WS, Brindisi M, Steffey M, Agniswamy J, Wang YF, Aoki M, Amano M, Weber IT, and Mitsuya H (2017) Design, Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and X-ray Studies of HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors with Modified P2’ Ligands of Darunavir, ChemMedChem 12, 1942–1952. DOI: 10.1002/cmdc.201700614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Amano M, Salcedo-Gomez PM, Zhao R, Yedidi RS, Das D, Bulut H, Delino NS, Sheri VR, Ghosh AK, and Mitsuya H (2016) A Modified P1 Moiety Enhances In Vitro Antiviral Activity against Various Multidrug-Resistant HIV-1 Variants and In Vitro Central Nervous System Penetration Properties of a Novel Nonpeptidic Protease Inhibitor, GRL-10413, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 7046–7059. DOI: 10.1128/AAC.01428-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hohlfeld K, Tomassi C, Wegner JK, Kesteleyn B, and Linclau B (2011) Disubstituted Bis-THF Moieties as New P2 Ligands in Nonpeptidal HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors, ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2, 461–465. DOI: 10.1021/ml2000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Cai Y, and Schiffer CA (2010) Decomposing the energetic impact of drug resistant mutations in HIV-1 protease on binding DRV, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 6, 1358–1368. DOI: 10.1021/ct9004678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nalam MN, Ali A, Reddy GS, Cao H, Anjum SG, Altman MD, Yilmaz NK, Tidor B, Rana TM, and Schiffer CA (2013) Substrate envelope-designed potent HIV-1 protease inhibitors to avoid drug resistance, Chem. Biol. 20, 1116–1124. DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Paulsen JL, Leidner F, Ragland DA, Kurt Yilmaz N, and Schiffer CA (2017) Interdependence of Inhibitor Recognition in HIV-1 Protease, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 2300–2309. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b01262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Leidner F, Kurt Yilmaz N, Paulsen J, Muller YA, and Schiffer CA (2018) Hydration Structure and Dynamics of Inhibitor-Bound HIV-1 Protease, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 14, 2784–2796. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Khan SN, Persons JD, Paulsen JL, Guerrero M, Schiffer CA, Kurt-Yilmaz N, and Ishima R (2018) Probing Structural Changes among Analogous Inhibitor-Bound Forms of HIV-1 Protease and a Drug-Resistant Mutant in Solution by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance, Biochemistry 57, 1652–1662. DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b01238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].King NM, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika EA, and Schiffer CA (2004) Combating susceptibility to drug resistance: lessons from HIV-1 protease, Chem. Biol. 11, 1333–1338. DOI: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Johnson VA, Calvez V, Gunthard HF, Paredes R, Pillay D, Shafer R, Wensing AM, and Richman DD (2011) 2011 update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1, Top. Antivir. Med. 19, 156–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Matayoshi ED, Wang GT, Krafft GA, and Erickson J (1990) Novel fluorogenic substrates for assaying retroviral proteases by resonance energy transfer, Science 247, 954–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Windsor IW, and Raines RT (2015) Fluorogenic Assay for Inhibitors of HIV-1 Protease with Sub-picomolar Affinity, Sci. Rep. 5, 11286 DOI: 10.1038/srep11286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ragland DA, Nalivaika EA, Nalam MN, Prachanronarong KL, Cao H, Bandaranayake RM, Cai Y, Kurt-Yilmaz N, and Schiffer CA (2014) Drug resistance conferred by mutations outside the active site through alterations in the dynamic and structural ensemble of HIV-1 protease, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 11956–11963. DOI: 10.1021/ja504096m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Meher BR, and Wang Y (2012) Interaction of I50V mutant and I50L/A71V double mutant HIV-protease with inhibitor TMC114 (darunavir): molecular dynamics simulation and binding free energy studies, J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 1884–1900. DOI: 10.1021/jp2074804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Foulkes JE, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Cooper D, Henderson GJ, Harris J, Swanstrom R, and Schiffer CA (2006) Role of invariant Thr80 in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease structure, function, and viral infectivity, J. Virol. 80, 6906–6916. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.01900-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Freedberg DI, Ishima R, Jacob J, Wang YX, Kustanovich I, Louis JM, and Torchia DA (2002) Rapid structural fluctuations of the free HIV protease flaps in solution: relationship to crystal structures and comparison with predictions of dynamics calculations, Protein Sci. 11, 221–232. DOI: 10.1110/ps.33202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Leonis G, Czyznikowska Z, Megariotis G, Reis H, and Papadopoulos MG (2012) Computational studies of darunavir into HIV-1 protease and DMPC bilayer: necessary conditions for effective binding and the role of the flaps, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 1542–1558. DOI: 10.1021/ci300014z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Leonis G, Steinbrecher T, and Papadopoulos MG (2013) A contribution to the drug resistance mechanism of darunavir, amprenavir, indinavir, and saquinavir complexes with HIV-1 protease due to flap mutation I50V: a systematic MM-PBSA and thermodynamic integration study, J. Chem. Inf. Model. 53, 2141–2153. DOI: 10.1021/ci4002102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Ragland DA, Whitfield TW, Lee SK, Swanstrom R, Zeldovich KB, KurtYilmaz N, and Schiffer CA (2017) Elucidating the Interdependence of Drug Resistance from Combinations of Mutations, J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 5671–5682. DOI: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hassan S, Srikakulam SK, Chandramohan Y, Thangam M, Muthukumar S, Gayathri Devi PK, and Hanna LE (2018) Exploring the conformational landscapes of HIV protease structural ensembles using principal component analysis, Proteins 86, 990–1000. DOI: 10.1002/prot.25534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Palese LL (2017) Conformations of the HIV-1 protease: A crystal structure data set analysis, Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 1865, 1416–1422. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ozen A, Lin KH, Kurt Yilmaz N, and Schiffer CA (2014) Structural basis and distal effects of Gag substrate coevolution in drug resistance to HIV-1 protease, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 15993–15998. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1414063111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].King NM, Melnick L, Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika EA, Yang SS, Gao Y, Nie X, Zepp C, Heefner DL, and Schiffer CA (2002) Lack of synergy for inhibitors targeting a multi-drug-resistant HIV-1 protease, Protein Sci. 11, 418–429. DOI: 10.1110/ps.25502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Barrie KA, Perez EE, Lamers SL, Farmerie WG, Dunn BM, Sleasman JW, and Goodenow MM (1996) Natural variation in HIV-1 protease, Gag p7 and p6, and protease cleavage sites within gag/pol polyproteins: amino acid substitutions in the absence of protease inhibitors in mothers and children infected by human immunodeficiency virus type 1, Virology 219, 407–416. DOI: 10.1006/viro.1996.0266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Rose JR, Salto R, and Craik CS (1993) Regulation of autoproteolysis of the HIV-1 and HIV-2 proteases with engineered amino acid substitutions, J. Biol. Chem. 268, 11939–11945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Hui JO, Tomasselli AG, Reardon IM, Lull JM, Brunner DP, Tomich C-SC, and Heinrikson RL (1993) Large scale purification and refolding of HIV-1 protease fromEscherichia coli inclusion bodies, J. Protein Chem. 12, 323–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Liu Y, Kati W, Chen CM, Tripathi R, Molla A, and Kohlbrenner W (1999) Use of a fluorescence plate reader for measuring kinetic parameters with inner filter effect correction, Anal. Biochem. 267, 331–335. DOI: 10.1006/abio.1998.3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Soumana DI, Kurt Yilmaz N, Ali A, Prachanronarong KL, and Schiffer CA (2016) Molecular and Dynamic Mechanism Underlying Drug Resistance in Genotype 3 Hepatitis C NS3/4A Protease, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11850–11859. DOI: 10.1021/jacs.6b06454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Otwinowski Z, and Minor W (1997) [20] Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode, Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. DOI: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, and Read RJ (2007) Phaser crystallographic software, J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674. DOI: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Emsley P, and Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics, Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132. DOI: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, and Zwart PH (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution, Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 213–221. DOI: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Moriarty NW, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, and Adams PD (2009) electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): a tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation, Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 65, 1074–1080. DOI: 10.1107/S0907444909029436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Brunger AT (1992) Free R value: a novel statistical quantity for assessing the accuracy of crystal structures, Nature 355, 472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB 3rd, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, and Richardson DC (2007) MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids, Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W375–383. DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkm216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Jayaraman S, and Shah K (2008) Comparative studies on inhibitors of HIV protease: a target for drug design, In Silico Biol. 8, 427–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Nalivaika EA, Romano K, and Schiffer CA (2006) Mechanism of substrate recognition by drug-resistant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease variants revealed by a novel structural intermediate, J. Virol. 80, 3607–3616. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3607-3616.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Sastry GM, Adzhigirey M, Day T, Annabhimoju R, and Sherman W (2013) Protein and ligand preparation: parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments, J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 27, 221–234. DOI: 10.1007/s10822-013-9644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Jorgensen WL, Maxwell DS, and Tirado-Rives J (1996) Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236. [Google Scholar]

- [69].Nalam MN, Ali A, Altman MD, Reddy GS, Chellappan S, Kairys V, Ozen A, Cao H, Gilson MK, Tidor B, Rana TM, and Schiffer CA (2010) Evaluating the substrate-envelope hypothesis: structural analysis of novel HIV-1 protease inhibitors designed to be robust against drug resistance, J. Virol. 84, 5368–5378. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.02531-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Pedregosa F, Varoquaux G, Gramfort A, Michel V, Thirion B, Grisel O, Blondel M, Prettenhofer P, Weiss R, and Dubourg V (2011) Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python, J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.